What about Sustainability? An Empirical Analysis of Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior in Fashion Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

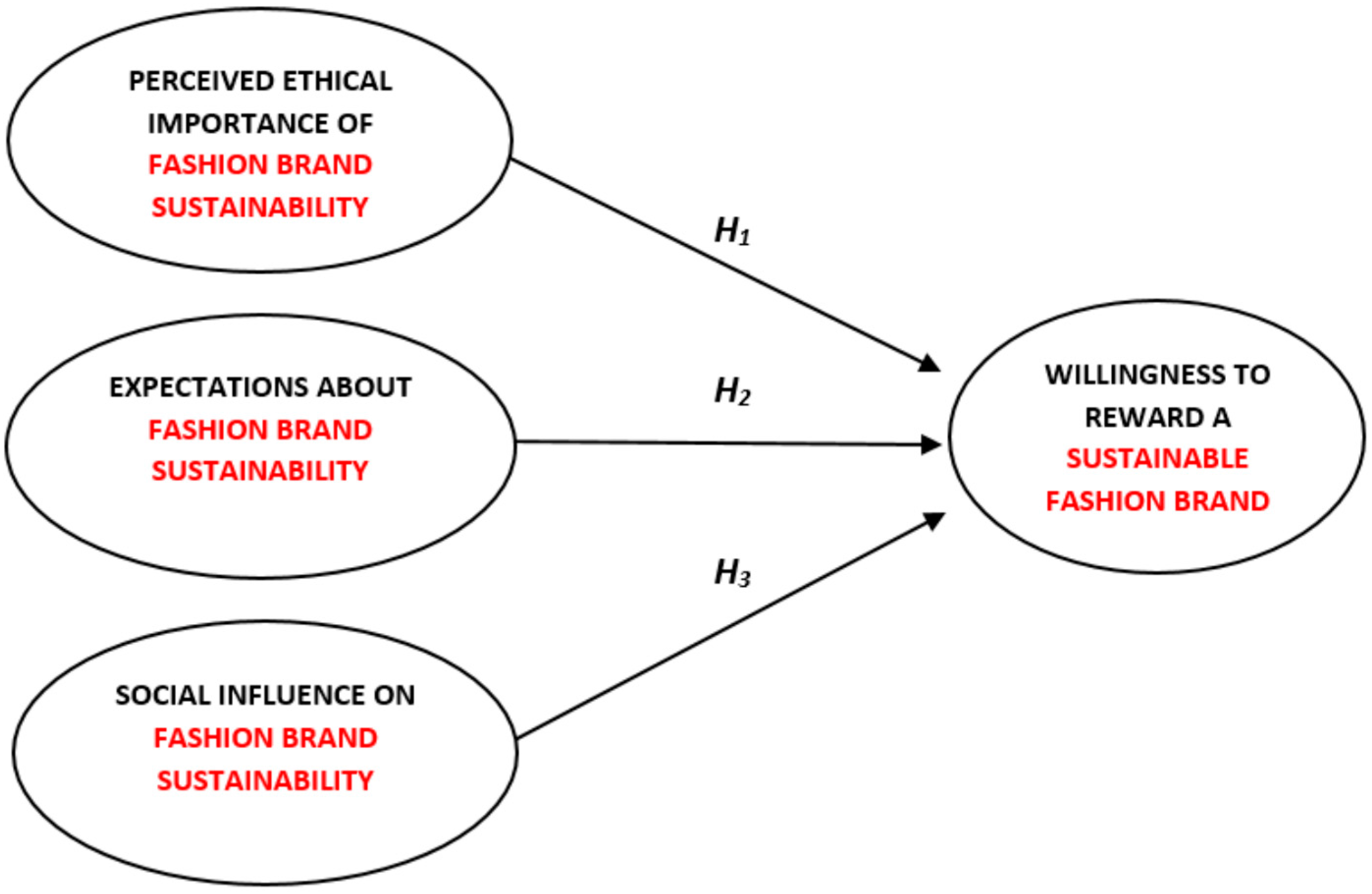

- Is it possible to imagine a theoretical model for the fashion world which is able to show whether “importance”, “expectations”, and “social influence” effectively affect consumers’ willingness to reward a sustainable fashion brand via their purchasing behavior?

- How much are consumers willing to pay in order to get a sustainable item of clothing?

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability

2.2. Perceived Ethical Importance

2.3. Expectations

2.4. Social Influence

3. Research Model and Hypothesis Development

- Importance of the ethicality of a firm’s behavior (importance).

- Expectations regarding the ethicality of corporate behavior in today’s society (expectations).

- Willingness to reward or punish an ethical firm via purchasing behavior (willingness to reward or punish).

Hypotheses Underlying the Model

4. Data Collection

4.1. Sample Description

4.2. Procedure and Instruments

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Theoretical and Practical Implications

8. Conclusions: Final Remarks, Limits and Future Research

- Is it possible to imagine a theoretical model for the fashion world that is able to show whether “importance”, “expectations”, and “social influence” effectively affect consumers’ willingness to reward a sustainable fashion brand via their purchasing behavior?

- How much are consumers willing to pay in order to get a sustainable item of clothing?

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainability: Consumer perceptions and marketing strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follows, S.B.; Jobber, D. Environmentally responsible purchase behavior: A test of a consumer model. Eur. J. Mark. 2000, 34, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- kerlof, G.A.; Kranton, R. Identity economics. Econ. Voice 2010, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, E.; Jiménez, F.R.; Gau, R. Concrete and abstract goals associated with the consumption of environmentally sustainable products. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1645–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.R.G.; Andersen, K.R. Sustainability innovators and anchor draggers: A global expert study on sustainable fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2015, 19, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Muhmin, A.G. Explaining consumers’ willingness to be environmentally friendly. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A.; Stafford, E.R.; Hartman, C.L. Avoiding green marketing myopia: Ways to improve consumer appeal for environmentally preferable products. Environ. Sci. Pol. Sustain. Dev. 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciasullo, M.V.; Troisi, O. The creation of sustainable value in SMES. A case study. Proceedings of 14th Toulon-Verona Conference Organizational Excellence in Services, Alicante, Spain, 1–3 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Polese, F. Local government and networking trends supporting sustainable tourism: Some empirical evidences. In Cultural Tourism and Sustainable Local Development; Girard, L.F., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 131–148. ISBN 978-0754673910. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S.; Saviano, M.; Polese, F.; Caputo, F. T-Shaped people for addressing the global challenge of sustainability. In Service Dominant Logic, Network and Systems Theory and Service Science: Integrating Three Perspectives for a New Service Agenda; Gummesson, E., Mele, C., Polese, F., Eds.; Giannini: Napoli, Italy, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 1–23. ISBN 9788874316847. [Google Scholar]

- Barile, S.; Saviano, M.; Polese, F.; Di Nauta, P. Il rapporto impresa-territorio tra efficienza locale, efficacia di contesto e sostenibilità ambientale. Sinerg. Ital. J. Manag. 2013, 90, 25–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.Y.; Sung, J. Sustainability and management in fashion, design and culture. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wang, Y.; Lo, C.K.; Shum, M. The impact of ethical fashion on consumer purchase behaviour. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, J. Examining relationships among sustainable orientation, perceived sustainable marketing performance, and customer equity in fast fashion industry. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2014, 5, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J.; Alevizou, P.J.; Young, C.W.; Hwang, K. Individual strategies for sustainable consumption. J. Mark. Manag. 2012, 28, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.; Oates, C.; Thyne, M.; Alevizou, P.; McMorland, L.A. Comparing sustainable consumption patterns across product sectors. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H.; Black, I.R.; Lee, M. Intentional non-consumption for sustainability: Consumer resistance and/or anti-consumption? Eur. J. Mark. 2011, 45, 1757–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Qu, S.; Lv, X. Chinese Local Government Innovation Sustainability Research. J. Public Adm. 2009, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Kronrod, A.; Grinstein, A.; Wathieu, L. Go green! Should environmental messages be so assertive? J. Mark. 2012, 76, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behavior when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilley, D. Design for sustainable behaviour: Strategies and perceptions. Des. Stud. 2009, 30, 704–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wever, R.; Van Kuijk, J.; Boks, C. User-centred design for sustainable behaviour. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2008, 1, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude-behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B.J. Recent developments in role theory. Ann. Rev. Soc. 1986, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R.; Surprenant, C.; Czepiel, J.A.; Gutman, E.G. A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.J.; Hicks, T. The Process of Business/Environmental Collaborations: Partnering for Sustainability, 1st ed.; Greenwood Publishing Group: Westport, CT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Méndez-Picazo, M.T.; Galindo-Martín, M.Á.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Governance, entrepreneurship and economic growth. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtomo, S.; Hirose, Y. The dual-process of reactive and intentional decision-making involved in eco-friendly behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, J.; Jacob, J. Green marketing: A study of consumers’ attitude towards environment friendly products. Asían Soc. Sci. 2010, 8, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Opportunities for green marketing: Young consumers. Mark. Int. Plan. 2008, 26, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Giau, A.; Macchion, L.; Caniato, F.; Caridi, M.; Danese, P.; Rinaldi, R.; Vinelli, A. Sustainability practices and web-based communication: An analysis of the Italian fashion industry. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 72–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pui-Yan Ho, H.; Choi, T.M. A Five-R analysis for sustainable fashion supply chain management in Hong Kong: A case analysis. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2012, 16, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, H.B. The Protestant Ethic versus the Spirit of Capitalism? Rev. Relig. Res. 1969, 10, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Sharma, R.D. Implications of corporate social responsibility on marketing performance: A conceptual framework. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Laczniak, G.R.; Murphy, P.E. Ethical marketing decisions: The higher road. J. Bus. Ethics 1994, 13, 858–886. [Google Scholar]

- Laczniak, G.R.; Murphy, P.E. Fostering ethical marketing decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 1991, 10, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E.; Laczniak, G.R.; Bowie, N.E.; Klein, T.A. Ethical Marketing, 1st ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 0131848143. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L.; Manceau, D.; Hémonnet-Goujot, A. Marketing Management, 14th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 0-13-145757-8. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-0-19-969731-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, R.C.; Richardson, W.D. Ethical decision making: A review of the empirical literature. In Citation Classics from the Journal of Business Ethics, 1st ed.; Michalos, A.C., Poff, D.C., Eds.; Springer: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 3, pp. 19–44. ISBN 978-94-007-4125-6. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, D.P.; Reidenbach, R.E. Social responsibility, ethics, and marketing strategy: Closing the gap between concept and application. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abratt, R.; Sacks, D. The marketing challenge: Towards being profitable and socially responsible. J. Bus. Ethics 1988, 7, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guffey, D.M.; Mccartney, M.W. The perceived importance of an ethical issue as a determinant of ethical decision-making for accounting students in an academic setting. Account. Educ. 2008, 17, 327–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, D.P.; Reidenbach, R.E.; Forrest, P.J. The perceived importance of an ethical issue as an influence on the ethical decision-making of ad managers. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 35, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, R.; Street, M.D.; Haines, D. The influence of perceived importance of an ethical issue on moral judgment, moral obligation, and moral intent. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapakdi, A. Perceived importance of ethics and ethical decisions in marketing. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 45, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, L.N.; Cronan, T.P.; Kreie, J. What influences IT ethical behavior intentions planned behavior, reasoned action, perceived importance, or individual characteristics? Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitell, S.J.; Hidalgo, E.R. The impact of corporate ethical values and enforcement of ethical codes on the perceived importance of ethics in business: A comparison of US and Spanish managers. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 64, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandakatiya, T.K.; Qiang, G.Y. The relationship between the ethical corporate culture and the perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility: Evidence from sri lankan government banking sector. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2014, 4, 290–303. [Google Scholar]

- Sciarelli, S. Business quality and business ethics. Total Q. Manag. 2002, 13, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarelli, S. Corporate ethics and the entrepreneurial theory of “social success”. Bus. Ethics Q. 1999, 9, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. Studying the ethical consumer: A review of research. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Newholm, T.; Shaw, D. The Ethical Consumer, 1st ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer-do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, K.H. Un/ethical company and brand perceptions: Conceptualising and operationalising consumer meanings. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 111, 551–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, K.H. Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandray, D. The ethical company. Work. 2000, 79, 74–77. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, J.M. The state of long-term expectation. In Essential Readings in Economics; Macmillan Education UK: London, UK, 1936; pp. 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, V.H. Work and Motivation; Robert, E., Ed.; Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, India, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. The nature of expectation and uncertainty. In Expectations, Uncertainty and Business Behavior; Social Science Research Council: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, J.C.; Dover, P.A. Disconfirmation of consumer expectations through product trial. J. Appl. Psychol. 1979, 64, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, C.; de Lange, F.P. Expectation in perceptual decision making: Neural and computational mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.A.; Venkatesh, V.; Goyal, S. Expectation confirmation in technology use. Inf. Syst. Res. 2012, 23, 474–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackle, G.L.S. Expectation in Economics; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kok, P.; Jehee, J.F.; de Lange, F.P. Less is more: Expectation sharpens representations in the primary visual cortex. Neuron 2012, 75, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.K. The expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Signal Proc. Mag. 1996, 13, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, R.N. An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. J. Mark. Res. 1965, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, E. Service attributes: Expectations and judgments. Psychol. Mark. 1993, 10, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.W. Motivational determinants of risk-taking behavior. Psychol. Rev. 1957, 64, 1–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J. Female achievement patterns: Attributions, expectancies, values, and choice. J. Soc. Issues 1983, 1, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Feather, N.T. Expectations and Actions: Expectancy-Value Models in Psychology; Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc.: Abingdon, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 3003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Pearo, L.K. A social influence model of consumer participation in network-and small-group-based virtual communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, T. Construction and Behavior Characteristics of Tyres. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 1959, 13, 157–191. [Google Scholar]

- Raven, B.H.; French, J.R. Group support, legitimate power, and social influence. J. Personal. 1958, 26, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Social Influence, 16th ed.; Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 1–206. [Google Scholar]

- White, K.M.; Smith, J.R.; Terry, D.J.; Greenslade, J.H.; McKimmie, B.M. Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 48, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 591–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M. A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. In Proceedings of the Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, Lincoln, NE, USA, 8–11 June 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, G.R.; Perrewé, P.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Lawong, D.; Holmes, J.J. Social Influence and Politics in Organizational Research. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2016, 24, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proc. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risselada, H.; Verhoef, P.C.; Bijmolt, T.H. Dynamic effects of social influence and direct marketing on the adoption of high-technology products. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frink, D.D.; Treadway, D.C.; Ferris, G.R. Social influence in the performance evaluation process. Blackwell Encycl. Dict. Hum. Res. Manag. 2005, 5, 346–349. [Google Scholar]

- Takács, K.; Flache, A.; Mäs, M. Is there negative social influence? Disentangling effects of dissimilarity and disliking on opinion shifts. PLoS ONE 2014, 11, e0157948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creyer, E.H. The influence of firm behavior on purchase intention: Do consumers really care about business ethics? J. Consum. Mark. 1997, 14, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, J.U.; Rahman, Z. Examining the effects of brand love and brand image on customer engagement: An empirical study of fashion apparel brands. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2016, 7, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Robson, A.; Coates, N. Chinese consumers’ purchasing: Impact of value and affect. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2013, 17, 486–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Chen, X.; Au, R. Consumer behavior of pre-teen and teenage youth in China. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2013, 4, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, M.; Mills, M. Uncovering Victoria’s Secret: Exploring women’s luxury perceptions of intimate apparel and purchasing behavior. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2013, 17, 460–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, O.; Zhu, X.; Liu, W.S. A study of the pyjamas purchasing behavior of Chinese consumers in Hangzhou. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2008, 12, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Rabolt, N.J.; Sook Jeon, K. Purchasing global luxury brands among young Korean consumers. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2008, 12, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, M.; Daly, L. Buyer behavior for fast fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2006, 10, 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, I.J.; Stephen, G.R. Buying behavior of “tweenage” girls and key societal communicating factors influencing their purchasing of fashion clothing. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2005, 9, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.M.; Steg, L.; Koning, M.A. Customers’ values, beliefs on sustainable corporate performance, and buying behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 555–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlek, C.; Steg, L. Human Behavior and Environmental Sustainability: Problems, Driving Forces, and Research Topics. J. Soc. Issues 2007, 63, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Rahman, Z.; Kazmi, A.A.; Goyal, P. Evolution of sustainability as marketing strategy: Beginning of new era. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 37, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.M.; Peattie, K. Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2008; ISBN 9780470519226. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, W.; Vanhonacker, F.; Sioen, I.; Van Camp, J.; De Henauw, S. Perceived importance of sustainability and ethics related to fish: A consumer behavior perspective. AMBIO 2007, 36, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Clarke-Hill, C.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. Marketing and sustainability. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherell, C.; Tregear, A.; Allinson, J. In search of the concerned consumer: UK public perceptions of food, farming and buying local. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Agriculture and the food industry in the information age. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakeu, J.; Byron, S. Optimistic about the future? How uncertainty and expectations about future consumption prospects affect optimal consumer behavior. BE J. Macroecon. 2016, 16, 171–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.J.; Sanfey, A.G. Great expectations: Neural computations underlying the use of social norms in decision-making. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2013, 8, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umbach, V. The Power of Prediction: Subjective Expectation Enables Efficient Behavior. Ph.D. Dissertation, Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, 17 December 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, L.I. On Role Expectation and Behavior Guiding in College Students. A Role Play-based Sociological Analysis. Soc. Sci. Beijing 2013, 4, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wang, Y. Consumer Behavior, Expectation and Retail Sales in Service Economy: Based on Household Survey Analysis. In Proceedings of the Management and Service Science (MASS), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 12–14 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, M. Consumer behavior towards continued use of online shopping: An extend expectation disconfirmation model. In Integration and Innovation Orient to E-Society; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 400–407. ISBN 978-0-387-75466-6. [Google Scholar]

- LaTour, S.A.; Peat, N.C. Conceptual and methodological issues in consumer satisfaction research. N. Am. Adv. 1979, 6, 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- Hiller Connell, K.Y.; Kozar, J.M. Social normative influence: An exploratory study investigating its effectiveness in increasing engagement in sustainable apparel-purchasing behaviors. J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2012, 3, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, G.S.; Capra, C.M.; Moore, S.; Noussair, C. Neural mechanisms of the influence of popularity on adolescent ratings of music. Neuroimage 2010, 49, 2687–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Costa, I.; Panchapakesan, P. A passion for fashion: The impact of social influence, vanity and exhibitionism on consumer behaviour. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2017, 45, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, K.L.; Stone, G.W. Social influence on post purchase brand attitudes. NA-Adv. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 740–746. [Google Scholar]

- Childers, T.L.; Rao, A.R. The influence of familial and peer-based reference groups on consumer decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1992, 19, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Clark, R.A. Materialism, status consumption, and consumer independence. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 152, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieke, S.E.; Fowler, D.C.; Chang, H.J.; Velikova, N. Exploration of factors influencing body image satisfaction and purchase intent: Millennial females. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 208–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I. Principal Component Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 0-471-41889-7. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelli, P.; Singh, H.; Singh, J.; Useem, M. The India Way: How India’s Top Business Leaders are Revolutionizing Management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2010, 24, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Experimental Designs Using Anova; Thompsone: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pett, M.A.; Lackey, N.R.; Sullivan, J.J. Making Sense of Factor Analysis: The Use of Factor Analysis for Instrument Development in Health Care Research; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Odom, T.W.; Lieber, C.M. Chemistry and physics in one dimension: Synthesis and properties of nanowires and nanotubes. Account. Chem. Res. 1999, 32, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.A.C.; Butcher, H.J. Teachers’ attitudes to education. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1968, 38, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A. An assessment of consumers product, purchase decision, advertising and consumption involvement in fashion clothing. J. Econ. Psychol. 2000, 21, 545–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosta, M.; Žabkar, V. Consumer sustainability and responsibility: Beyond green and ethical consumption. Trziste/Market 2016, 28, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

| Administrated Questionnaires | Response Rate | Non-Response Rate | Response Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| 310 | 271 (87, 42%) | 20 (6, 45%) | 19 (6, 13%) |

| Variables | Scales Validity | Scales Reliability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KMO Test | Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (Sign.) | Total Explained Variance | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

| Importance | .500 | .000 | 90.469 | .895 |

| Expectation | .781 | .000 | 55.429 | .794 |

| Social influence | .716 | .000 | 83.548 | .901 |

| Willingness to reward | .716 | .000 | 75.513 | .819 |

| Model | R | R-Square | Adjusted R-Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Durbin-Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | .812 | .660 | .656 | .721 | 1.802 |

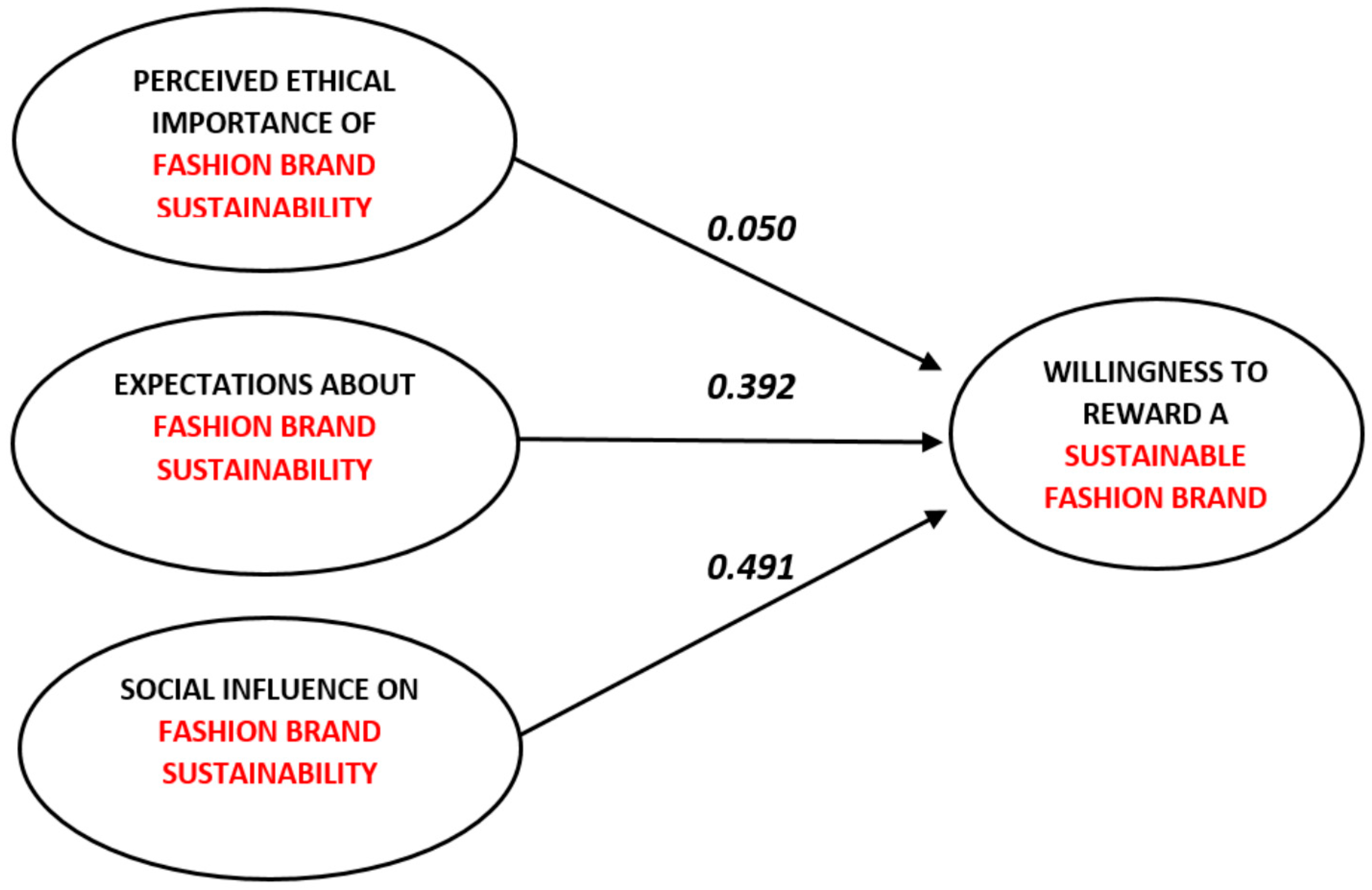

| Variables | Standardized Beta | Sign. | Collinearity Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIF | Tolerance | |||

| Importance | .050 | .281 | .602 | 1.660 |

| Expectation | .392 | .000 | .486 | 2.057 |

| Social influence | .491 | .000 | .674 | 1.484 |

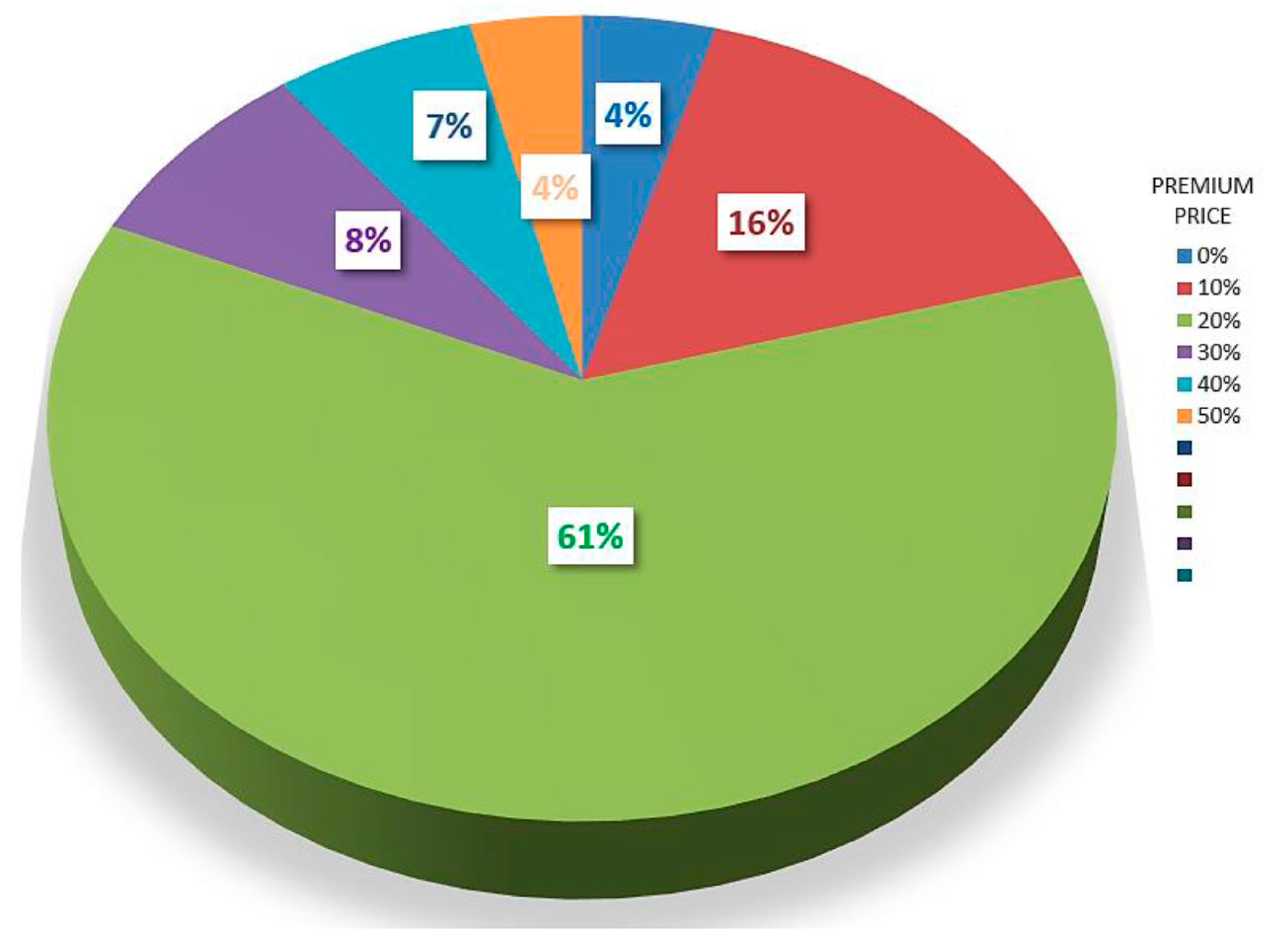

| People (% of the Sample) | Maximum Premium Price Willing to Pay |

|---|---|

| 10 (4%) | 0% |

| 43 (16%) | 10% |

| 165 (61%) | 20% |

| 22 (8%) | 30% |

| 19 (7%) | 40% |

| 10 (4%) | 50% |

| 0 (0%) | 60% |

| 0 (0%) | 70% |

| 0 (0%) | 80% |

| 0 (0%) | 90% |

| 0 (0%) | 100% |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciasullo, M.V.; Maione, G.; Torre, C.; Troisi, O. What about Sustainability? An Empirical Analysis of Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior in Fashion Context. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091617

Ciasullo MV, Maione G, Torre C, Troisi O. What about Sustainability? An Empirical Analysis of Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior in Fashion Context. Sustainability. 2017; 9(9):1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091617

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiasullo, Maria Vincenza, Gennaro Maione, Carlo Torre, and Orlando Troisi. 2017. "What about Sustainability? An Empirical Analysis of Consumers’ Purchasing Behavior in Fashion Context" Sustainability 9, no. 9: 1617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091617