An Investigation into Risk Perception in the ICT Industry as a Core Component of Responsible Research and Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Responsible Research and Innovation

2.2. Risk Assessment

- Those that observe or calculate the risk of a process.

- Those that rely upon the perceptions of individuals.

2.3. Ethical and Societal Risks Associated with R&I in ICT

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling Method

3.2. The Interviews

3.3. Two-Round Delphi Study

- Awareness of RRI

- Integration of RRI into the product value chain

- Responsible governance

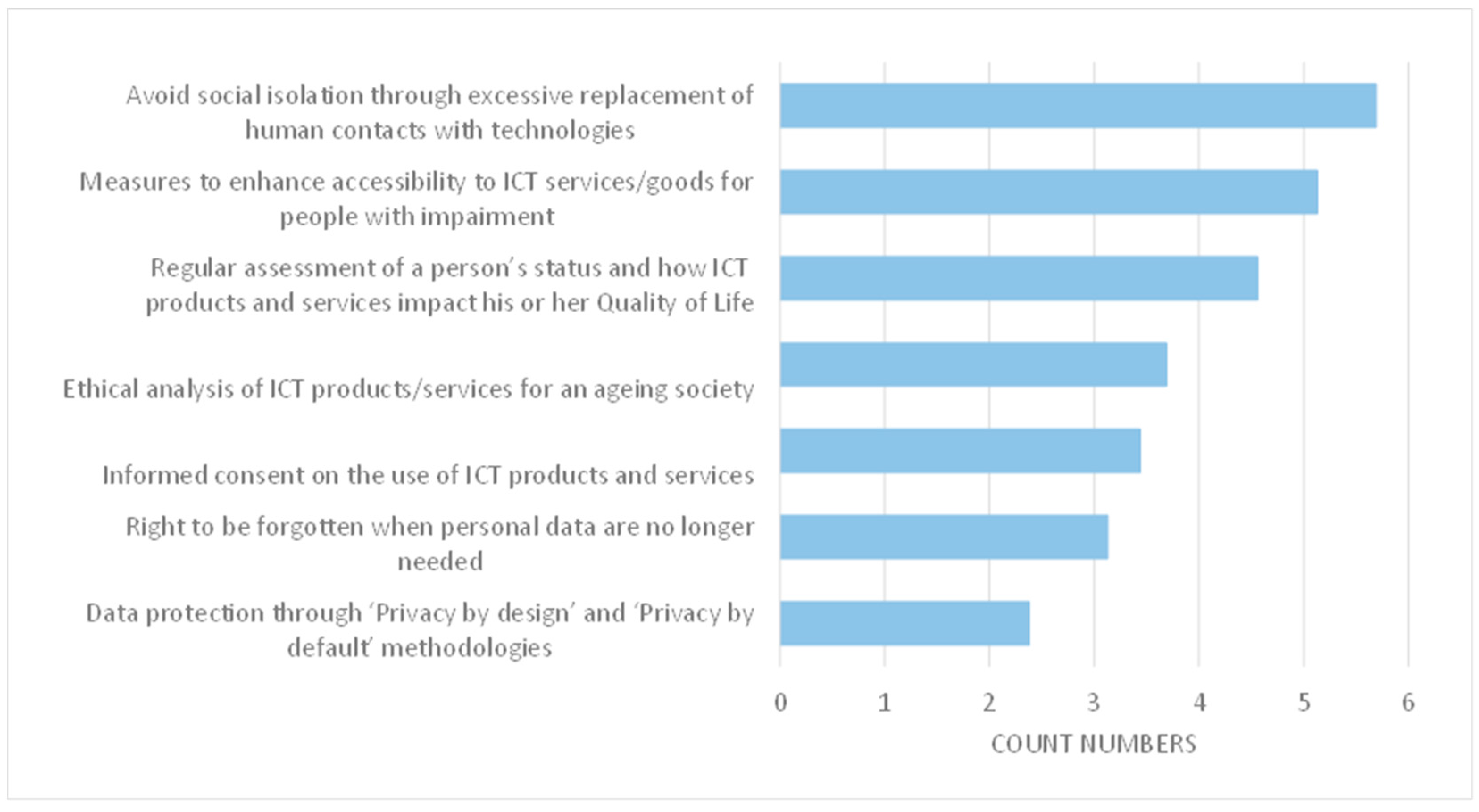

- Inclusion of RRI dimensions in the ICT for ageing society area.

4. Results

4.1. Summary of Participants

4.2. Results from the Interviews

4.2.1. Profit Assurance

“It would be almost stupid to do something without having all the stakeholders involved … we would probably be out of business if we don’t deliver what works or what solves real need.”(13)

“There are standards in place … but those standards refer mainly to performance and quality control as opposed to having any specific ethical content.”(28)

“We do not use specific procedures to evaluate the risk of unintended consequences of our product development.”(19)

“In general, inside our company, we do not have any professional ethical code. It is sufficient for us to use our moral intuitions, based on our experience, to evaluate if the data are sensitive or not. We ask our customers to sign a waiver to discharge us from legal liability.”(20)

4.2.2. Profit Plus

“Our research and development work is always carried out with the end-users, like persons with dementia and their relatives … The most significant action in our development work is to involve the end-users into process. All research and development should be based on actual needs and have significant meaning to the target group.”(5)

“(Risk assessment) is a part of the consumer design in the first place. So you have to understand the effects of the products, the effects of manufacturing the products, the effects from the raw materials and of course the effects can be social, they can be physical, they can be medical … following how we make our products, what we make our products from and so on.”(15)

“We include worldwide risk assessment also providing information as to which risks they are within different countries, different geographical areas, and for different kinds of all the vendors that we have with regards to labour and the environment and their level of effects.”(24)

“Because the idea was great but the outcome, during development, shows that this potentially could not be useful or used in the market because of the potential risks that are discovered.”(6)

4.2.3. Data Management

“The issue, in terms of responsible research and innovation, has come with the use of actual patient records technology and sharing the data across organisations of individuals and health care professionals and who has secondary rights to that data for the purposes of research and how to manage the governance around that.”(3)

“We have to handle and manage a massive amount of sensitive data and information in health care. We have in place all the protocols that are necessary to guarantee data protection and safety.”(21)

4.3. Results from the Delphi Study

4.3.1. What the Risks Are

- Transmission of data to a third party (3.5/5)

- Reasoning systems for privacy–sensitive data analysis (for example, noise analysis for activity recognition) (3.4/5)

- Brain–computer interface (3.4/5).

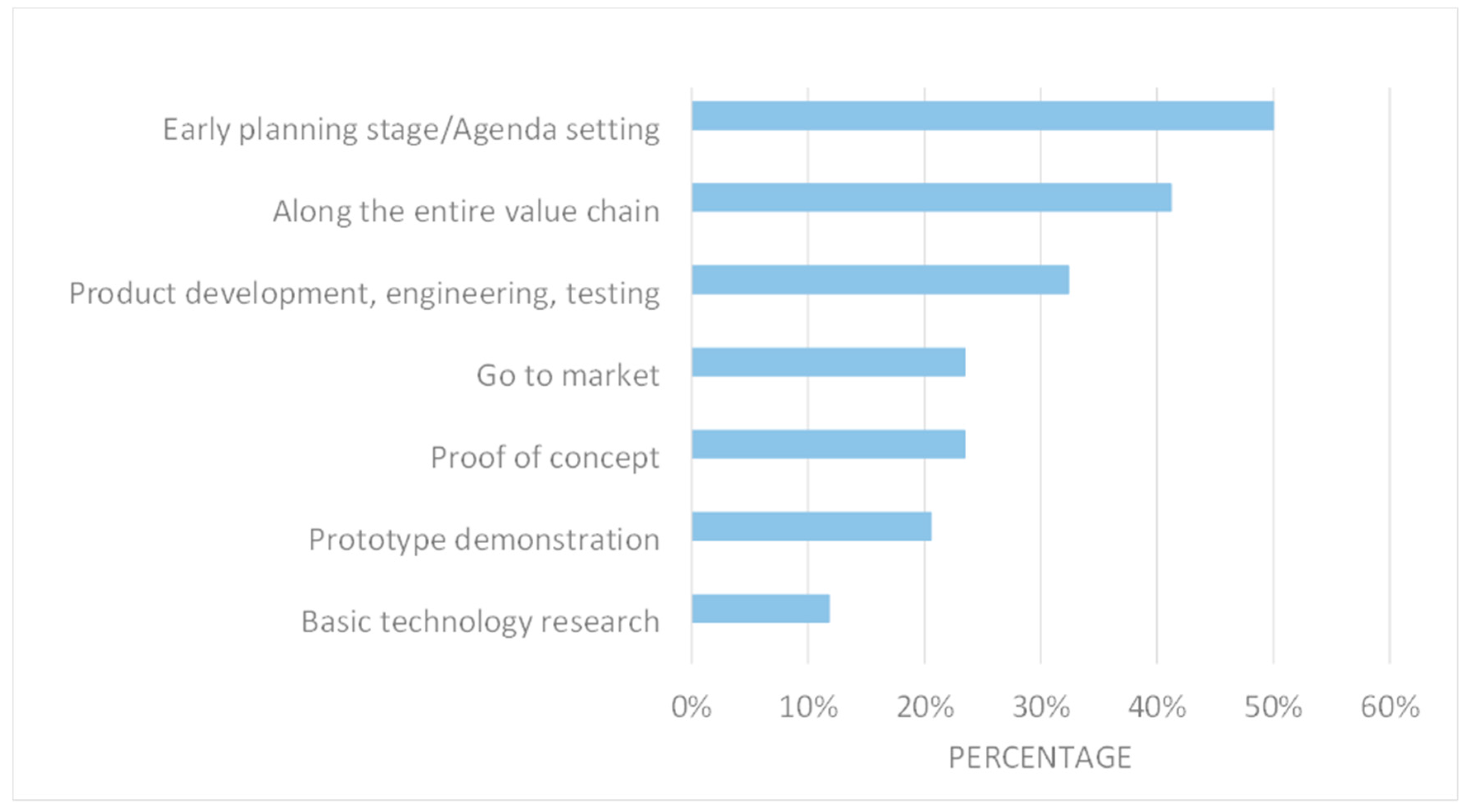

4.3.2. When to Address Risks

“I disagree with this approach—no amount of early planning can prepare the delivery organisations for the perception issues they must deal with when going into the market.”(D13)

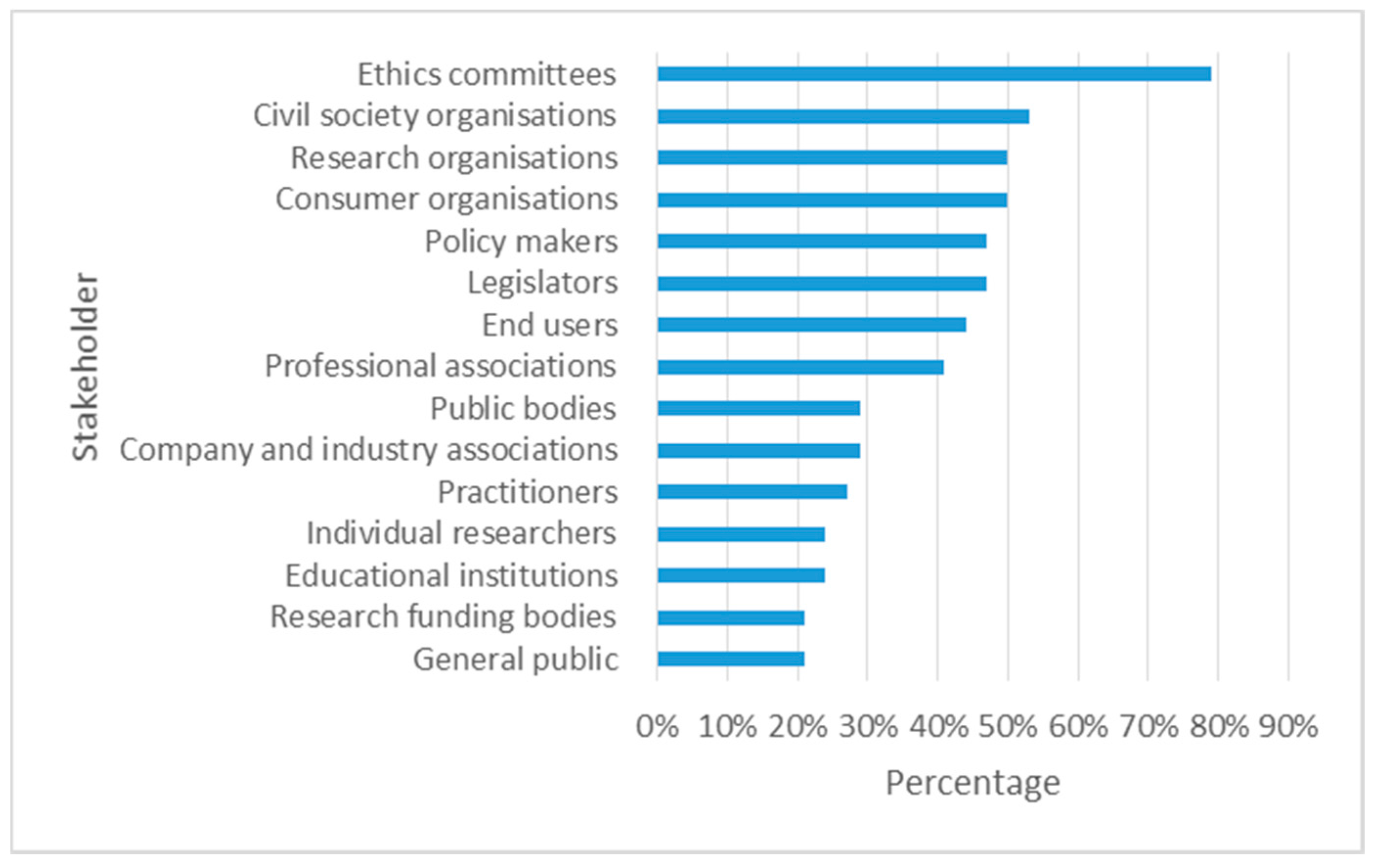

4.3.3. Who Should Address the Ethical and Societal Risks?

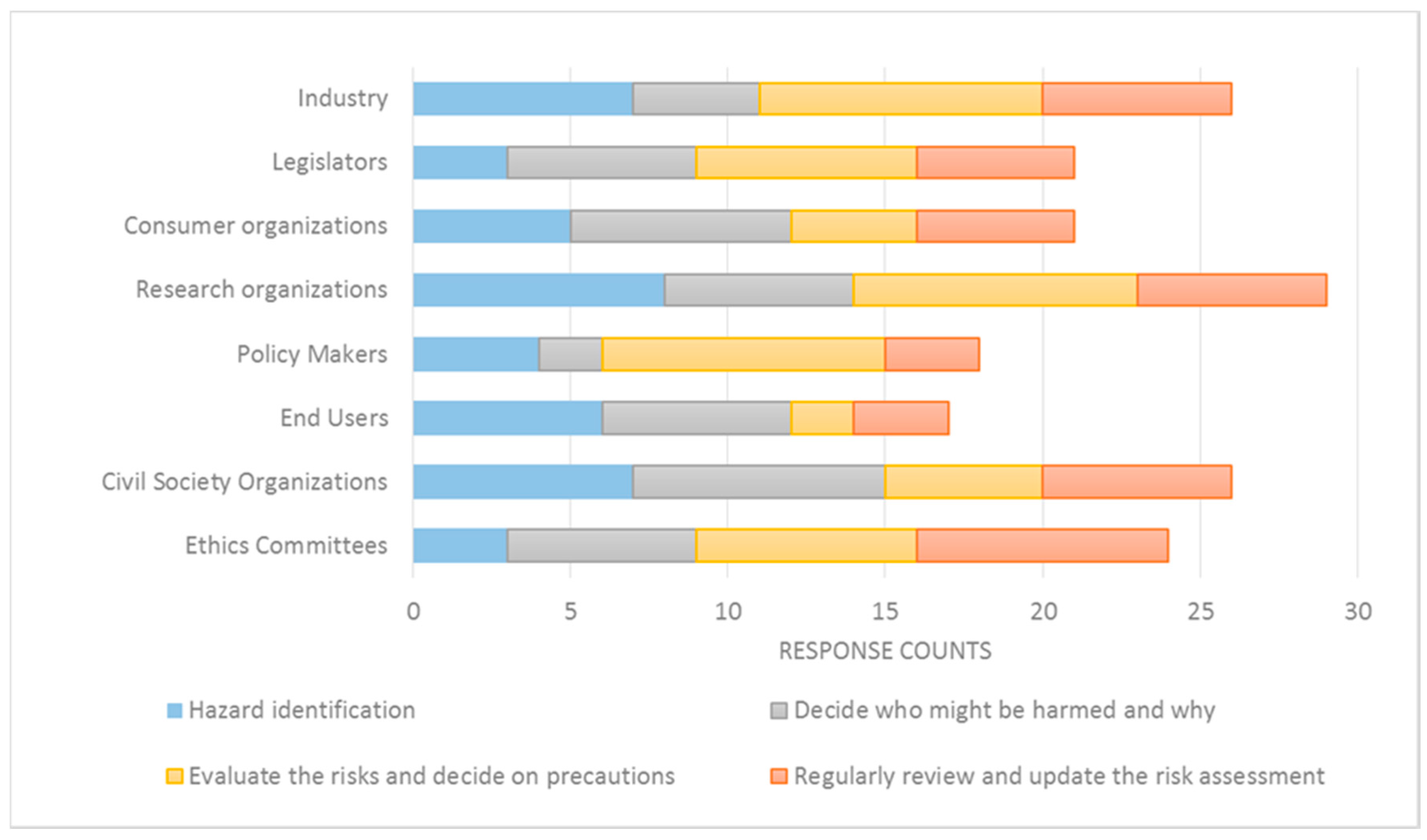

4.3.4. How to Address the Risks

- Ethical assessment (78%)

- Risk assessment procedures (71%)

- Pilot studies for evaluating different scenarios (44%)

- List of moral values (44%).

“I believe the failures are typically in the execution of the methodologies, rather than in the methodologies themselves.”(D2)

- Need for rules on personal data protection that are valid for all companies, regardless of their establishment, inside or outside Europe (75%)

- Need for a single pan-European regulation for personal data protection (67%)

- Insufficient in terms of personal data protection (58%)

- Insufficient in terms of specific legislation on e-Health, including mobile health practices (50%)

4.3.5. A Culture of Responsible Research and Innovation

“There is no real need for new tools or more bureaucracy, but, instead, for a change of thinking. RRI should be part of the company philosophy. The management should be responsible for propagating this philosophy throughout the company, creating a company culture in which every department and employee act responsibly.”(D21)

“Most people are not aware of the risks of new technologies, as, for example, seen by the imprudent use of social networks and cloud services. Therefore, we need more education and an open discussion of technology impacts and societal responsibility.”(D21)

“I agree from a general point of view, but social aspects, ethics, and responsibility cannot be taught to adults with years of experience.”(D11)

5. Discussion

- (1)

- Degree of innovationThe enterprises that develop products which are at the forefront of R&I are more responsive to ethical and societal issues.

- (2)

- Interface with end-usersEnterprises that develop products or services that involve direct interface with end-users are more likely to undertake activities for engagement/involvement of end-users to increase acceptability/desirability of the products/services.

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Indicative Interview Questions

- (1)

- The purpose of this interview is to seek your opinions about RRI in industry. Is that a concept you have ever come across before? (Probe further here if necessary and help by offering suggestions to find out about particular ways of how RRI can be recognised in practice)

- (2)

- In your experience what are the key drivers for this type of activity? (e.g., who is in charge, are there any requirements for, and what are people’s motivations?)

- (3)

- In your experience, what are the main challenges for development and implementation of RRI?

- (4)

- What do you think would need to be in place to help with those challenges?

- (5)

- In what ways is consideration paid to your target or end-users in research and innovation activities? (e.g., who is consulted in the development phase, who benefits from it and why these groups, do you interact with NGOs?)

- (6)

- What attention is paid to codes of conduct in your company? (e.g., do you have any particular protocols in place to consider ethical aspects of research and innovation? How do professional ethical codes have an impact? If none, then any idea why not?)

- (7)

- What attention is paid to ISO or other certifications in your company?

- (8)

- To what extent does your company attempt to predict (unintended) consequences of your product development and later product use, in particular, when it comes to impact on the environment, society, and the well-being of users? (Ask about any methods used in this assessment)

- (9)

- Have you or would you consider making the results of your research and/or other innovation data openly available? (What would be the benefits or reasons why not?)

- (10)

- Anything else you would like to add?

Appendix B

| Code | Country of Origin | Type of Business | Size | Position Held |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cyprus | Medical technology | SME | Founder/Chief executive |

| 2 | Cyprus | Research/technology | SME | Employee |

| 3 | UK | Data management | SME | Partner |

| 4 | UK | Consultancy/e-health | SME | Director |

| 5 | France | Health robotics | Large | Marketing |

| 6 | Switzerland | Medical technology | Large | Vice president |

| 7 | UK | Medical data solutions | SME | National manager |

| 8 | Germany | Medical technology | Large | Chief executive officer |

| 9 | Germany | Medical technology | Large | Development manager |

| 10 | Spain | ICT | Large | Project manager |

| 11 | Spain | Telemedicine | SME | Chief technology officer |

| 12 | Spain | ICT | SME | Chief executive officer |

| 13 | Finland | Green IT | SME | Global sourcing |

| 14 | Germany | Engineering | SME | Head of programme |

| 15 | Finland | Telecommunications | Large | Head of Innovation |

| 16 | NL | R&I | SME | Researcher |

| 17 | NL | R&I | SME | President |

| 18 | NL | Technology | Large | Research director |

| 19 | Italy | Telecommunications | Large | Project manager |

| 20 | Italy | ICT | SME | Information systems manager |

| 21 | Italy | Web healthcare apps | SME | Project worker |

| 22 | Denmark | ICT | SME | Head of research |

| 23 | Denmark | Technology | SME | Business development manager |

| 24 | Denmark | Technology | SME | Business development manager |

| 25 | Finland | ICT | SME | Development manager |

| 26 | Spain | Immersive technologies | SME | Research & development Manager |

| 27 | UK | Health NGO | SME | Programme lead |

| 28 | Spain | Technology | Large | International director |

| 29 | UK | Technology for elderly | Large | Chief executive officer |

| 30 | Sweden | ICT | Large | Vice president |

Appendix C

| Delphi Code | Country of Origin | Type of business | Size | Position Held |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Switzerland | IT sector | SME | Business Consultant |

| 2 | Switzerland | IT services and solutions | SME | Project Manager |

| 3 | Turkey | e-Health | SME | Researcher |

| 4 | Finland | Sustainable development | SME | Director |

| 5 | Italy | Biotechnology/healthcare | SME | Manager |

| 6 * | Finland | Healthcare | SME | Owner |

| 7 | Germany | Healthcare | Large | Team Leader |

| 8 * | Spain | Home care and telecare | SME | CEO |

| 9 | Netherlands | Innovation | Large | Innovation Consultant |

| 10 * | Austria | e-Health | SME | Project leader |

| 11 * | Italy | Telecommunications | Large | Project manager |

| 12 * | Sweden | IT solutions for the elderly | SME | CEO |

| 13 * | Greece | ICT (e-Health) | SME | Manager |

| 14 * | Italy | Visualisation products | SME | Innovation Manager |

| 15 | Cyprus | R&I | SME | Manager |

| 16 * | Italy | IT solutions | SME | Director |

| 17 * | Germany | IT-Automation | SME | CEO |

| 18 | Norway | Ambient Assisted Living | SME | CEO |

| 19 * | Germany | Healthcare | Large | Sales strategy manager |

| 20 | Germany | Healthcare | Large | Information systems worker |

| 21 * | Germany | Home fitness | SME | Manager |

| 22 | Finland | Sustainable Development | SME | CEO |

| 23 | Sweden | Technology | SME | Manager |

| 24 | Sweden | Telecare for the elderly | SME | Product manager |

| 25 | - | - | Large | - |

| 26 | Cyprus | Innovation | SME | Research Engineer |

| 27 * | Belgium | Care for the elderly | Large | Director |

| 28 * | Italy | e-Healthcare | Large | Project Assistant |

| 29 * | Greece | Telemedicine | Large | Project Manager |

| 30 | Finland | Welfare innovations | SME | CEO |

| 31 | Finland | Architectural innovations | Large | Director |

| 32 | UK | - | SME | General Manager |

| 33 | Finland | IT services and solutions | SME | Business Development manager |

| 34 | Finland | Financial services | SME | Researcher |

| 35 ** | Germany | ICT | SME | Project Leader |

References

- Markus, M.L.; Mentzer, K. Foresight for a responsible future with ICT. Inf. Syst. Front. 2014, 16, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C.; Eden, G.; Jirotka, M. Responsible research and innovation in information and communication technology: Identifying and engaging with the ethical implications of ICTs. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Heintz, M., Bessant, J., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Responsible Research and Innovation—Europe’s Ability to Respond to Societal Challenges. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/responsible-research-and-innovation-leaflet_en.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Iatridis, K.; Schroeder, D. Responsible Research and Innovation in Industry: The Case for Corporate Responsibility Tools; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Horizon 2020, the EU framework Programme for Research and Innovation: Ethics. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/ethics (accessed on 30 January 2017).

- Von Schomberg, R. Prospects for technology assessment in a framework of responsible research and innovation. In Technikfolgen Abschätzen Lehren: Bildungspotenziale Transdisziplinärer Methoden; Dusseldorp, M., Beecroft, R., Eds.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011; pp. 39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R.; Goldberg, N. Responsible innovation: A pilot study with the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1699–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, R.; Bessant, J.; Heintz, M. Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Options for Strengthening Responsible Research and Innovation. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/options-for-strengthening_en.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Owen, R. The UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council’s commitment to a framework for responsible innovation. J. Responsib. Innov. 2014, 1, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, K.; Iatridis, K.; Stahl, B.C.; Paspallis, N. Innovating Responsibly in ICT for Ageing: Drivers, Obstacles and Implementation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, R.; Stilgoe, J.; Macnaghten, P.; Gorman, M.; Fisher, E.; Guston, D. A framework for responsible innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schomberg, R. A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, A. Responsible innovation: Bringing together technology assessment, applied ethics, and STS research. Enterp. Work Innov. Stud. 2011, 7, 9–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnin, C.; Amanatidou, E.; Keenan, M. Orienting European innovation systems towards grand challenges and the roles that FTA can play. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuhls, K. From forecasting to foresight processes—New participative foresight activities in Germany. J. Forecast. 2003, 22, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georghiou, L.; Harper, J.C.; Keenan, M.; Miles, I.; Popper, R. The Handbook of Technology Foresight: Concepts and Practice; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenhofer, K. Risk Assessment of Emerging Technologies and Post-Normal Science. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2011, 36, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, M. Guidebook on Social Impact Assessment. 2005. Available online: http://www.versatel.ebc.net.au/CCA%20SIA%20Guidebook.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2017).

- Schirmer, J. Scaling up: Assessing social impacts at the macro-scale. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, D.; de Hert, P. Introduction to privacy impact assessment. In Privacy Impact Assessment; Wright, D., de Hert, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.G.; Petts, J. Adaptive governance for responsible innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Heintz, M., Bessant, J., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 143–164. [Google Scholar]

- Scholten, V.; Blok, V. Foreword: Responsible innovation in the private sector. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2015, 15, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, T.; Fitzgerald, M.; Kitzinger, J.; Laurie, G.; Price, J.; Rose, N.; Rose, S.; Singh, I.; Walsh, V.; Warwick, K. Novel Neurotechnologies: Intervening in the Brain; Nuffield Council on Bioethics: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malsch, I. Responsible innovation in practice—Concepts and tools. Philos. Reformata 2013, 78, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubberink, R.; Blok, V.; van Ophem, J.; Omta, O. Lessons for responsible innovation in the business context: A systematic literature review of responsible, social and sustainable innovation practices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility; Harvard Business School Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beyleveld, D.; Brownsword, R. Complex technology, complex calculations: Uses and abuses of precautionary reasoning in law. In Evaluating New Technologies: Methodological Problems for the Ethical Assessment of Technology Developments; Sollie, P., Düwell, M., Eds.; Springer: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S. New technologies, common sense and the paradoxical precautionary principle. In Evaluating New Technologies: Methodological Problems for the Ethical Assessment of Technology Developments; Sollie, P., Düwell, M., Eds.; Springer: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, D.; Friedewald, M. Integrating privacy and ethical impact assessments. Sci. Public Policy 2013, 40, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, R.G. Perceptions of risk and their effects on decision making. In Societal Risk Assessment: How Safe Is Safe Enough? Schwing, R.C., Albers, W.A., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 71–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S. Science and Public Reason; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Raz, T.; Michael, E. Use and benefits of tools for project risk management. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2001, 19, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covello, V.T.; Merkhoher, M.W. Risk Assessment Methods: Approaches for Assessing Health and Environmental Risks; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, B.; Whittington, M. Reflecting on whether checklists can tick the box for cloud security. In Cloud Computing Technology and Science, 2014 IEEE 6th International Conference (CloudCom); Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S. The songlines of risk. Environ. Values 1999, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowska, P. Civil society involvement in the EU regulations on GMOs: From the design of a participatory garden to growing trees of European public debate. J. Civil Soc. 2007, 3, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schomberg, R. Towards Responsible Research and Innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2436399 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2436399 (accessed on 14 April 2017).

- Quilici-Gonzalez, J.; Kobayashi, G.; Broens, M.; Gonzalez, M. Ubiquitous computing: Any ethical implications? Int. J. Technoethics 2010, 1, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaghan, V.; Clarke, G.; Chin, J. Some socio-technical aspects of intelligent buildings and pervasive computing research. Intell. Build. Int. 2009, 1, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Poel, I.; Nihlén Fahlquist, J.; Doorn, N.; Zwart, S.; Royakkers, L. The problem of many hands: Climate change as an example. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2012, 18, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moor, J.H. What is computer ethics? Metaphilosophy 1985, 16, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moor, J.H. Why we need better ethics for emerging technologies. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2005, 7, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, N.F.; Coombs, C.R.; Loan-Clarke, J. A re-conceptualization of the interpretive flexibility of information technologies: Redressing the balance between the social and the technical. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Floridi, L. The Cambridge Handbook of Information and Computer Ethics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Hoven, J.; Weckert, J. Information Technology and Moral Philosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, B.C.; Timmermans, J.; Mittelstadt, B.D. The Ethics of Computing: A Survey of the Computing-Oriented Literature. ACM Comput. Surv. 2016, 48, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, T.L.; Childress, J.F. Principles of Biomedical Ethics; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, C. Informed consent and the Facebook emotional manipulation study. Res. Ethics 2016, 12, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavani, H.T. Genomic research and data-mining technology: Implications for personal privacy and informed consent. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2004, 6, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Crandall, R. Ethics in Social and Behavioral Research; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J.H. The interview. From neutral stance to political involvement. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 695–727. [Google Scholar]

- Dewar, J.A.; Friel, J.A. Delphi Method; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 208–209. [Google Scholar]

- Helmer, O.; Gordon, T.J. Report on a Long-Range Forecasting Study; The RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1964; p. 2982. [Google Scholar]

- Joint Research Centre. Delphi Survey. Available online: http://forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/guide/4_methodology/meth_delphi.htm (accessed on 1 February 2017).

- Linstone, H.A.; Mitroff, I.I. The Challenge of the 21st Century: Managing Technology and Ourselves in a Shrinking World; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Linstone, H. Multiple Perspectives Revisited; IAMOT: Orlando, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Spinuzzi, C. The methodology of participatory design. Techn. Commun. 2005, 52, 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, M. Methods to support human-centred design. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2001, 55, 587–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, M.; Ikonen, V.; Leikas, J.; Kantola, K.; Kulju, M.; Tammela, A.; Ylikauppila, M. Human-driven design: A human-driven approach to the design of technology. In IFIP International Conference on Human Choice and Computers; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Nicholls, C.M.; Ormston, R. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, C.R.; De Angeli, A. Applying user centred and participatory design approaches to commercial product development. Des. Stud. 2014, 35, 614–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, A.D. The innovation high ground: Winning tomorrow’s customers using sustainability-driven innovation. Strateg. Dir. 2006, 22, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P.; Stilgoe, J. Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. Sci. Public Policy 2012, 39, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, B.C.; Timmermans, J.; Flick, C. Ethics of emerging information and communication technologies on the implementation of responsible research and innovation. Sci. Public Policy 2016, 44, 369–381. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K.A. Can Effective Risk Management Signal Virtue-Based Leadership? J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarre, E.; Levy, C.; Twining, J. Taking Control of Organizational Risk Culture. McKinsey Working Papers on Risk: 2010. Available online: http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk/our-insights/taking-control-of-organizational-risk-culture (accessed on 28 January 2017).

| Category | Explanation | Company Sizes |

|---|---|---|

| Profit assurance | Risk assessment is viewed primarily as profit-related; stakeholder engagement will help to increase product/service acceptance and associated sales. | SME = 10 Large = 4 Total = 14 |

| Profit plus | Risk assessment is necessary to ensure profit but is also important for addressing broader societal needs (such as environmental concerns etc.) | SME = 6 Large = 4 Total = 10 |

| Data management | Risk assessment is primarily concerned with data management and protection. | SME = 2 Large = 1 Total = 3 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chatfield, K.; Borsella, E.; Mantovani, E.; Porcari, A.; Stahl, B.C. An Investigation into Risk Perception in the ICT Industry as a Core Component of Responsible Research and Innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081424

Chatfield K, Borsella E, Mantovani E, Porcari A, Stahl BC. An Investigation into Risk Perception in the ICT Industry as a Core Component of Responsible Research and Innovation. Sustainability. 2017; 9(8):1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081424

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatfield, Kate, Elisabetta Borsella, Elvio Mantovani, Andrea Porcari, and Bernd Carsten Stahl. 2017. "An Investigation into Risk Perception in the ICT Industry as a Core Component of Responsible Research and Innovation" Sustainability 9, no. 8: 1424. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9081424