Towards Sustainable Clothing Disposition: Exploring the Consumer Choice to Use Trash as a Disposal Option

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (Q-1)

- How do consumers reach their disposal decisions?

- (Q-1a)

- What is the process by which consumers arrive at the decision to use trash as a disposal option?

- (Q-2)

- What are the barriers that keep consumers from using alternatives to the trash for their clothing disposal?

- (Q-3)

- What knowledge do consumers have about the post-consumer textile waste stream?

- (Q-3a)

- What needs to be done to increase the use of disposal options other than trash?

2. Related Literature and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Consumer Apparel Disposal

2.2. Post-Consumer Textile Waste Stream

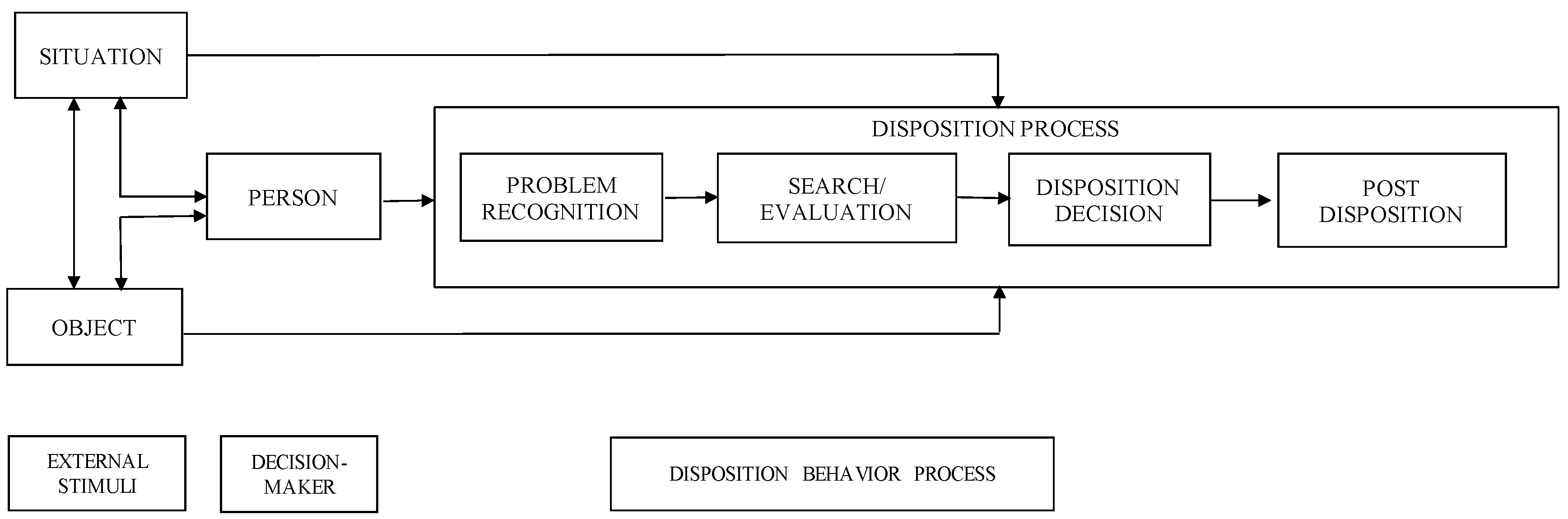

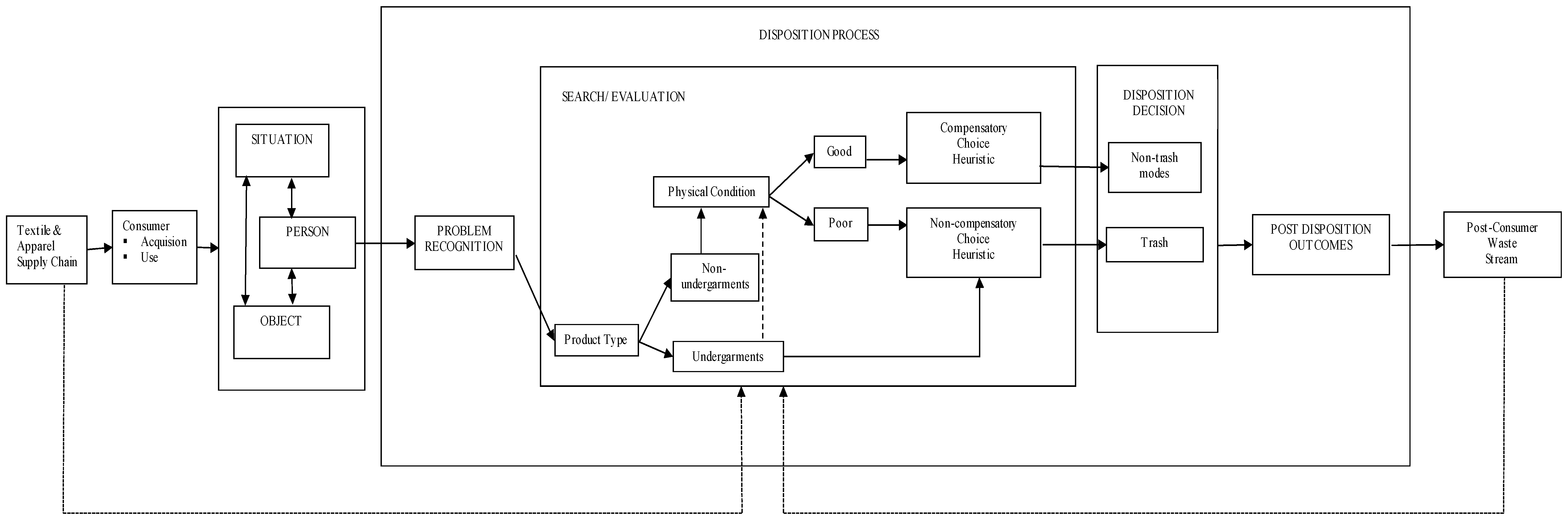

2.3. Consumer Disposition Behavior Process Model

3. Methods

4. Results

4.1. How Do Consumers Reach Their Disposal Decisions? What Is the Process by Which Consumers Arrive at the Decision to Use Trash as a Disposal Option?

4.1.1. Compensatory Choice Heuristic

Well, first I look at things that need to be repaired or cleaned, or whatever, and then if I wash them, and the spots don’t come out, they just go into a Goodwill bag. I take the things that are the least good to Goodwill and then the moderate things go to Salvation Army … My good things, that are still decent but I’m just tired of wearing, go to Upscale Resale. Sometimes I have taken some more current pieces to Plato’s Closet.(Susan)

As I look at them, I decide, okay, is this something that could be used at Dreams to Reality? Is this something that they could use for their boutique sale? Is this something that would be better going to USAgain? Or is this something I could just throw away?(Mary)

So it’s kind of that way with Upscale Resale, because their market is more gently used-still in style, certainly quite a bit of life left, whereas, things that I’d put in the Goodwill box look like they are just not that same level of quality. Things that I would look at as having value to them I separate from things that would not meet their criteria but still be usable to someone.(Dianne)

4.1.2. Non-Compensatory Choice Heuristic

4.2. What Are the Barriers That Keep Consumer from Using Alternatives to the Trash for Their Clothing Disposal?

4.2.1. Usable Life of Garment

Seems like something I would not want to buy secondhand so why would I expect anybody else … to buy my secondhand stuff like that. Well, the nylons, if I’m getting rid of nylons, they have a hole in them. So, they’re like worthless at that point.

No one’s going to want to buy a shirt that has a stain on it, you know what I mean? So, I don’t want to pass it on to someone else, and have them (the donation site) decide to throw it away because no one’s going to buy a shirt with a stain on it.

4.2.2. Personal Nature of Garment

4.3. What Knowledge Do Consumers Have about the Post-Consumer Textile Waste Stream? What Would Need to Be Done to Increase the Use of Disposal Options Other Than the Trash?

4.3.1. Need to Create Awareness

I know Patagonia has a clothing recycling program. You can send your stuff back. So, when I’ve had some of their stuff, and there’s holes everywhere because I would wear it so much, I would return it to them, and they would recycle it. But, I thought it had to be a special program.

4.3.2. Need for Assurance

You know I just realized that they do take it (underwear), but, you know, that’s just such a personal thing. I know it’s anonymous, and nobody knows, but I would hate to think that somebody would look at something, and judge me, even if they don’t know me.

You know, I don’t know. And I don’t know why it makes me feel uncomfortable. Because, obviously, they [the underwear] are clean, I would wash them before I’d take them. I just never considered it, and you know, I don’t throw away that much, or get rid of that much. So, I probably would consider it.

5. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Council for Textile Recycling. Available online: http://www.weardonaterecycle.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2017).

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Textile and Apparel Industry-A Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.; Hawley, J. Envisioning the Clothing and Textile-Related Discipline for the 21st Century Its Scientific Nature and Domain from the Global Supply Chain Perspective. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 31, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winakor, G. The Process of Clothing Consumption. J. Home Econ. 1969, 61, 629–634. [Google Scholar]

- Norum, P.S. Trash, Charity and Secondhand Stores: An Empirical Analysis of Clothing Disposition. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2015, 40, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbert, S.A.; Horne, S.; Tagg, S. Charity retailers in competition for merchandise: Examining how consumers dispose of used goods. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.W. A proposed paradigm for consumer product disposition processes. J. Consum. Aff. 1980, 14, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Berning, C.K.; Dietvorst, T.F. What about dispositions? J. Mark. 1977, 8, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Brookshire, J.; Hodges, N. Socially responsible consumer behavior? Exploring used clothing donationbehavior. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2009, 27(3), 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, P.; Perea, B. From trash to treasure and beyond: The meaning of voluntary disposition. J. Consum. Behav. 2009, 8, 340–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Cárdenas, J.; Gonzáles, R.; Gascó, J. Clothing Disposal System by Gifting: Characteristics, Processes, and Interactions. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2017, 35, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, J. Digging for diamonds: A conceptual framework for understanding reclamined textile products. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2006, 24, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Birtwistle, G. Sell, give away, or donate: An exploratory study of fashion clothing disposal behaviour in two countries. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2010, 20, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregson, N.; Metcalfe, A.; Crewe, L. Practices of object maintenance and repair. J. Consum. Cult. 2009, 9, 248–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, L.R.; Birtwistle, G. An investigation of young fashion consumers’ disposal habits. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, K.; Domina, T. Consumer textile recycling as a means of solid waste reduction. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 1999, 28, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domina, T.; Koch, K. Convenience and Frequency of Recycling Implications for Including Textiles in Curbside Recycling Programs. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtwistle, G.; Moore, C.M. Fashion clothing—Where does it all end up? Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2007, 35, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivoli, P. The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy: An Economist Examines the Markets, Power, and Politics of World Trade; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior, 10th ed.; Thomson South-Western: Mason, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hultgren, F.H. Introduction to Interpretive Inquiry. In Alternative Modes of Inquiry in Home Economic Research; Hultgren, F.H., Coomer, D.L., Eds.; AHEA: Washington, DC, USA, 1989; pp. 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, G.D. The Long Interview; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, L.; Wisenblit, J. Consumer Behavior, 11th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spiggle, S. Analysis and Interpretation of Qualitative Data Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Norum, P.S. Towards Sustainable Clothing Disposition: Exploring the Consumer Choice to Use Trash as a Disposal Option. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071187

Norum PS. Towards Sustainable Clothing Disposition: Exploring the Consumer Choice to Use Trash as a Disposal Option. Sustainability. 2017; 9(7):1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071187

Chicago/Turabian StyleNorum, Pamela S. 2017. "Towards Sustainable Clothing Disposition: Exploring the Consumer Choice to Use Trash as a Disposal Option" Sustainability 9, no. 7: 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071187