3.1. The Role of Village Cadres

The development trajectory of the LSC shows that despite the prominence of incentives for individual rural household in their agricultural production and allocation of resources, village cadres are still responsible for many village-wide political activities and economic decisions. As rural elites, they actively participate in village governance and institutional innovations. On one hand, their activities are constrained by local politics and community. On the other hand, these constraints are not equal to limitation and are sometimes also a motivation.

The cadre responsibility system is a formal evaluation system used by superiors to measure a local officials’ performance. It is widely applied to incentivize a variety of goals (like local economic growth, the one-child policy, or social stability), resulting in complex “report cards” which matter for officials’ monetary reward/punishment, and more importantly their promotion [

18,

19]. Such political incentive leads to selective policy implementation by local officials. For example, in rural areas the land issue is often in dispute. If the land allocation is adjusted by force or requisitioned without adequate compensation, peasants will resort to group petitioning to claim their rights where such events will hamper a local cadres’ career success. Accordingly they are motivated to pursue institutional changes related to land tenure reforms. Initiated by village cadres, the LSC facilitates them to fulfill priority targets in their evaluation.

De-collectivization fundamentally changes the configuration of power in rural China. The implementation of the electoral system has not only changed the source of power of village cadres, but also improved the village governance. Faced with the loosening of political control and peasants’ growing sense of democracy, village cadres must rely on villagers to carry out economic programs. They must draft policies consistent with peasants’ interests. “In Shanglin, each peasant has only 0.6 mu (0.04 hectare) of arable land on average and it is difficult to make a fortune on it. The youth under 30 prefer to study and work in the city, which also raises their social status. We must find a way to enrich everyone’s living in the village. I am first a peasant, like other villagers, and I understand their expectations. The land cooperative can help achieve agricultural modernization and it is up to us (village cadres) to take the initiative.” remarked Xi Yuexin, the CCP branch secretary. Rural democratization has changed local cadres’ behavior. They no longer respond only to their superiors’ orders, but devote more effort to the public affairs. They have become the representatives of the villagers [

20].

The role of village cadres and their own interests are closely intertwined. As a rational agent, the ultimate goal of the rural leadership is utility maximization. Village cadres’ salaries are financed by the village, so their income is directly linked to village’s fiscal revenue. A decent salary enables cadres to concentrate more on implementing policies and managing rural affairs. The cadre responsibility system scores and ranks village cadres every year: The top ones are awarded the title of Model Leader, which will increase their chance of promotion. Ambitious and in their early 30s with a high school or college diploma, young village cadres all seek promotion within the bureaucratic hierarchy, even if it is not their first priority.

As a local resident, village cadres have family relationship or close friendship with other villagers, and their social interest is deeply rooted in the cultural network and daily life in the village. The closer the personal network, the more important the reputation or “faces” for village cadres, the more aggressive they are to utilize various resources to meet villagers’ needs and improve their welfare. Often, they try not to satisfy the superiors at the expense of local peasants.

Village cadres’ income levels, career path, as well as their social status in the local community all depend on whether they can retain the position in the villagers committee. They are the lowest-level executives to implement rural policies, but they also belong to the village community and work closely with fellow peasants. They must balance their personal interests, interests of township government and all the higher authorities, and those of their local constituents [

21].

Land-use right, one of China’s most scarce resources is an effective instrument to help achieve village cadres’ goals. They use their de facto control over land resources to discipline villagers, with a carrot-and-stick approach [

22]. In the case of Shanglin LSC, the land-use right is concentrated and each villager is guaranteed a dividend of RMB 600 (

$75) per mu (1 mu = 0.067 hectare) and enjoys priority job opportunities in the cooperative. The financial success of the cooperative even allows the village to pay a portion of the taxes/fees on behalf of villagers. The cooperative also helps village cadres achieve other priority targets, like family planning: Those households with a new-born single child are entitled to an additional 0.0067 hectare of land (thus more dividends) immediately as a reward to birth control, while it takes five years for other increased population to obtain lands.

The presence of the state power, the speed of marketization and the extent of community integration are three key factors defining the role of village cadres [

23]. During the era of reform, the delegation of powers allows localities to make their own decision and rebuild the intact structure of the village. With the weakening of state power, the dominance and mobilization ability of village cadres actually depends on their relationship with peasants [

24] (p. 83). Village cadres, through a triangular structure of the state, locality and villagers, explore a legitimate way to maximize the community’s interest. With the de facto control over land bestowed by the state, they build up a profit allocation mechanism with peasants through a certain type of rural collective organization. The application of such mechanism in Shanglin village is the LSC.

3.2. Peasants’ Attitude towards the LSC

The setting up of the LSC is the occasion of a confrontation between different interest groups: The State, the village community, and the peasants. Each group takes cost-benefit calculations beforehand, so it cannot be pre-assumed that all peasants would actively support this cooperative project. Individual decisions must be explained by taking into account both the cultures and the process by which the individual arbitrates between the different possibilities available to him and the influences that come through interactions with others [

25] (p. 370). Our analysis is based on a field survey conducted in Shanglin village.

3.2.1. Survey Results

Four main features emerged from the results:

Survey respondents may underreport their household income. Shanglin is an affluent village, according to CCP branch secretary Xi Yuexin. Its annual per capita income was RMB 11,800 (

$1685) in 2008, 2.5 times the rural income at the national level that year. Yet, there are discrepancies between the level of income according to our survey and the figures offered by Xi. More than 75% of the surveyed families (usually comprised of three to four people) claim that their household income was less than RMB 30,000 (

$4285) per year, as shown in

Table 1. It is probable that peasants chose not to disclose their actual income since this subject is taboo, despite the anonymity of the questionnaire. Only 18% of those surveyed work full-time in agriculture (

Table 2), while most villagers work in non-agricultural industries like rural enterprises and family workshops, the sectors which the majority of their household income comes from (

Table 3).

Our survey finds that the LSC is widely accepted by peasants: Not only did all surveyed villagers join the cooperative, 60% of them enthusiastically did so in the first place. In the process of popularizing the cooperative, there are three categories of participants: The pioneers, the influential, and others [

25] (p. 38). Unlike the circulation of land-use right (land transfer or subletting) which was a spontaneous act between peasants, to participate in the LSC by converting their land into shares is collective behavior. In their decision making process, individuals have to prudently calculate the costs involved but also pay attention to social motives [

26].

More than 90% of the surveyed villagers admitted that when joining the LSC they did not understand how it operates, yet their ignorance did not keep them away. This new type of land tenure reform lacks role models or regulations and only 11.7% of respondents had experience with other forms (

Table 4). The peasants have difficulty understanding the theoretical and ambiguous concepts, most of them only remembering the name, yet they still embraced it. It may be due to three main reasons, as show in

Table 5. Firstly, most villagers work in non-agricultural sectors and do not have enough time to take care of their land. More than one third of the surveyed peasants hope that the new LSC can free them from heavy farm work. Secondly, villagers expect that the cooperative may produce more financial benefits: 23.4% of respondents believe that the centralized large-scale agricultural production can generate more income than traditional farming on the dispersed farmland. Finally, in a rural community with limited mobility and where families have interacted with each other for generations, it is necessary for peasants to be concerned about the reaction of fellow villagers and to comply with the social rules [

27]. Thirty-six percent of the respondents decided to follow the crowd to join the LSC, so as not to offend the majority of the villagers and not to be excluded from the community.

On the other hand, 49% of the survey respondents were not fully satisfied with the decision making process for the establishment of the cooperative. The Shanglin LSC was initiated by village cadres, approved by the village committee, and legitimized by the local CCP branch. In the process of this collective behavior, each phase of decision making and the resulting consequences were closely monitored by individual villagers. Prior to the start of the cooperative, documents on the LSC system were posted on the public bulletin boards in the village. CCP branch members and village representatives were summoned to discuss the plan. Village representatives were then sent out to collect opinions of ordinary peasants and report to the village committee. Despite all these efforts, still half of the survey respondents were not satisfied. They think that though they were allowed to express opinions, the final decision was made by a small group of village cadres but not the general assembly of the village.

3.2.2. Logistic Regression Results

Based on the survey data we incorporate into the regression households’ certain socio-economic characteristics (gender, age, education, profession, health condition, and income level) and some external factors likely to influence their willingness to join the cooperative.

Table 6 and

Table 7 summarize these variables in the LR model and

Table 8 reports the regression results.

Three main findings emerge from the regression results.

It is revealed that full-time peasants are reluctant to join the cooperative, while there isn’t significant relation between those working in non-agricultural industries and their intention to join the cooperative. During our interviews a few peasants confirmed that despite rough farm work, they still want to keep their individual tangible land (rather than intangible shares in the LSC), which defines their identity in the village. In this way, the LSC system may not be applicable in a traditional agricultural region where most villagers are full-time peasants.

There is a significantly positive relation between a peasant’s health condition and his/her incentive to join the cooperative. Contracted farm land cannot be sold (or subleased quickly) to cover large medical expenses; rather, the land cannot generate any income in case of incapacitating illness. Those who are concerned about their health conditions (especially the elderly), instead of rendering their land idle, are willing to convert them into cooperative shares for a dividend.

There is also a significantly positive relation between those who are willing to contribute to rural pension scheme and their incentive to join the cooperative. The pension scheme was recently introduced to rural China and those who are most willing to make payments are in their 40–50s, approaching retirement ages (

Table 9). They are fully aware that they are not able to undertake farm work for long and that there may not be routine financial support from their children. Pension plans and membership in the LSC will become two effective livelihood guarantees when they get old.

The relation between villagers’ incentive to join the cooperative and their education or income level is statistically insignificant (though the signs of estimated coefficients are intuitive), which is against our initial expectation. As discussed in

Section 3.2.1, more than 90% of surveyed villagers were ignorant about the LSC system before joining the cooperative. So we argue that in the case of Shanglin higher education levels do not contribute to better knowledge of the cooperative, and in turn do not have a statistically significant relation with villagers’ incentive. We also notice that the increased annual income from the cooperative’s dividend is small with RMB 210 (

$30) per capita ((600 − 250) × 0.6 = 210), taking up less than 2% of Shanglin villagers’ average annual income in 2008. With existing decent income from other industries, income improvement is not the top two reasons (as seen in

Table 5) to influence villagers’ decision to join the LSC and the negative relation between the income level and their willingness is statistically insignificant.

From both the survey and regression results, we clearly find that Shanglin peasants’ economic behavior is neither incompetent nor irrational; they shrewdly calculate the gain or loss before decision making. While they are not isolated individuals, but must behave according to the current rules in the society they belong to, so they are influenced by their entourage. The cooperative, as a mechanism of change initiated by village cadres, is essentially collective and social in nature. It is within this common system that everyone calculates for themselves, whereas the system should impose its logic so that individual projects can be combined.

3.3. Performance of the Land Shareholding Cooperative System

The land shareholding cooperative system is a major institutional innovation in rural China since the introduction of the household responsibility system (hereafter, referred to as responsibility system) in the late 1970s. It retains the incentive mechanism derived from the responsibility system, while overcoming the disadvantages of equitable distribution of farmland. It is like a compromised improvement/modification to the land contractual rights. Respecting the collective ownership, thus circumventing the strict institutional restrictions, the LSC system enables a moderate concentration and large-scale exploitation of rural land. A Pareto improvement, it achieves economic, social, political, and environmental progress.

The LSC system allocates different elements within the right of ownership (abusus, usus, fructus, and possessio) to different entities. The right to dispose land (abusus and possessio) remains in the hands of the village community while the right to use land (usus) is held by the cooperative who then grants this right to individuals/enterprises by contract. The right to drive profit from land (fructus) is shared between the community, the cooperative’s shareholders, and land contractors. This separation of rights allows different interest groups to obtain their own financial gains according to their specific right.

Peasants’ benefit is clarified through the quantification of rural land resources by professional accounting and auditing agencies. Their status as shareholders in the cooperative is ensured by the share certificate, which in turn guarantees their claim on the dividends every year. On the other hand, the LSC derives income mainly from leasing the farmland. By registering with the local government and obtaining an operating license, the cooperative strengthens its management rights and is under judicial and administrative protection in case of any dispute.

The LSC system represents a hybrid form of capitalist shareholding, and socialist cooperative institutions [

28]. The cooperative’s members, as principals, authorize the cooperative as an agent to manage farmland on their behalf and thereby entrust part of their decision-making power to the agent. In general, there might be a principal-agent problem. The solution is that the cooperative be administered by elected member representatives. Suggested by the local CCP branch, every thirty households of villagers form one villagers group. Each group elects one delegate with the highest votes as the member representative. The general meeting of member representatives becomes the decision-making body in the cooperative. The LSC system is characterized by its indivisible relationship between shareholders and managers. Representatives, board of directors, and board of supervisors are members of the cooperative at the same time; they share common interests with ordinary members.

The LSC system reduces agricultural production risk faced by peasants, providing them with a more stable income through dividends and job opportunities. Dividend payment from the cooperative which increases each year offers villagers mainly undertaking non-agricultural activities a means of “leaving the farmland without leaving their native land”. Although peasants abandon their individual usus, the cooperative guarantees their fructus and accompanied profits, and lowers their opportunity cost to participate in industrialization and urbanization. Some villagers, especially women and the elderly who may not easily find a job in TVEs can greatly supplement their household income by working for the cooperative.

The LSC also enables sustainable land use through ecological farming. Experts from Suzhou Agricultural Research Institute were recruited to develop new crop varieties and selenium-enriched rice was introduced for large-scale production. Priced as high as $2 per kilogram, this type of rice is pre-booked even before the harvest. In the farmland auction organized by the LSC, ecological farming is considered a priority and those projects enjoy a discounted rent. Small pilot fields are even offered freely to certain projects like Bonsai cultivation.

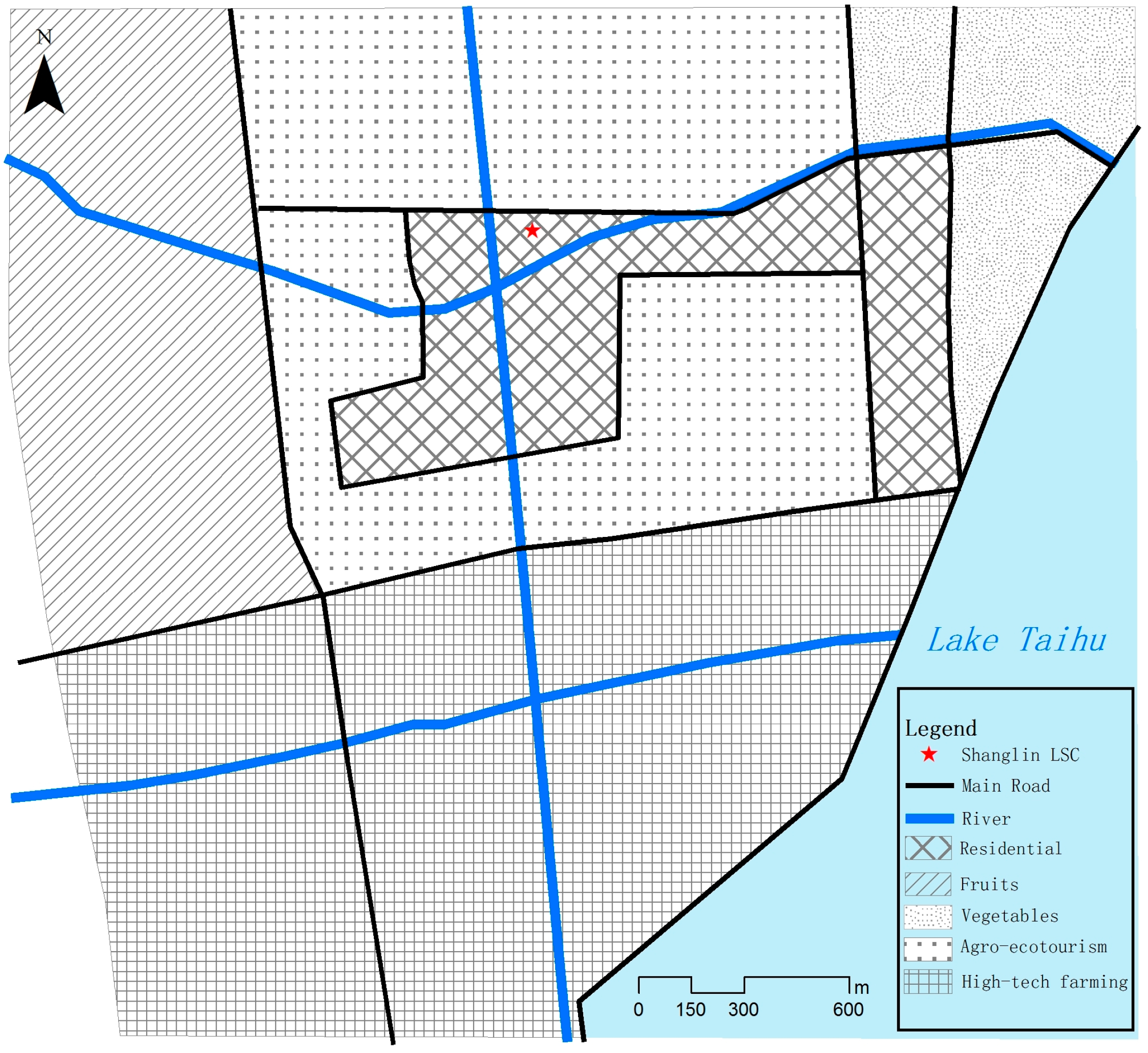

By consolidating peasants’ land-use right, the cooperative centralizes the decision-making power over land management and investment, so that peasants as a whole have more bargaining power in the market. The cooperative carries out land utilization planning for various purposes: agricultural zone, residential area, and industrial zone. Thanks to the cooperative’s coordination, plots for residential purpose are concentrated and the land intended for agriculture is also connected after the exchange of plots. This adjustment greatly facilitates the land leveling projects. The cooperative is in charge of infrastructure construction such as roads, electricity, telecommunications, water supply, and natural gas. Then it conducts tenders of land-use right, collects rents and distributes dividends among member peasants. In addition, the cooperative forms a powerful entity to prevent encroachment upon their land and to protect their interests.

The LSC system motivates the rural population to participate in free elections so that villagers are no longer excluded from village governance. The cooperative is governed by its elected members who are actively involved in policy drafting and decision making. According to articles 10 and 11 of Shanglin LSC Charter, “every member in the cooperative has the right to vote and to be elected representative of the members. Every member has the right to supervise the finance and administration of the cooperative”. Also the general meeting of member representatives votes to ratify the principle of private plots adjustment and the LSC Charter. These regulations are accepted by all members and become internal disciplines for the village community and serve as a reference tool to reconcile conflicts.

The LSC is an ideal entity to internalize the positive externalities of public goods. Shares held by the Association of Economic Cooperation (AEC, a branch of village government we discussed in

Section 2.1) generate proceeds to provide public service to the village community. For example, three multi-purpose activity rooms with daily maintenance are offered to all villagers free of charge. The cooperative strengthens environmental governance: RMB 900,000 (

$128,570) was spent by the LSC on the construction of water conservation systems and sewage treatment works. It also invested RMB 7 million (around

$1 million) on waste disposal and reforestation. Regular street sweeping, 230 trash dumpsters and a 16,000-m-long river canal are well maintained by 35 people recruited by the LSC.

As a new institutional arrangement, the LSC system helps achieve liquidity in factors of production (labor and land) and increased agricultural productivity. This system maintains collective ownership of land while transferring peasants’ land contractual rights to shares in the cooperative in order for optimal land use and management. It did not depart from the egalitarian principle of distribution, but tried to figure out a compromise between equity and efficiency.

3.4. Deficiencies in Shanglin LSC

The LSC system is developed in a context of legal ambiguity in the definition of collective ownership and a complex political-economic relationship. Despite Shanglin LSC’s decent financial and social performance, this arrangement is far from perfect and its loss of efficiency in certain aspects may hamper its long-term development.

Its organization is characterized by the merger of the villagers committee, the CCP branch and the cooperative, so the LSC performs economic, political and social functions at the same time. Its objectives are not confined to productivity improvement or profit maximization, but also include job creation and public service provision. The Shanglin LSC offers its villagers more than 100 jobs related to security, sanitation, electric power, and plumbing and it also partially sponsors the salary paid to village cadres like the head of the women’s association. Such spending amounts to RMB 1.5 million (more than $0.2 million) each year. The LSC also pays for villagers’ social security, provides minimum living allowance to certain poor peasants and rewards those pursuing college education or joining the army.

There may be some clash between the administrative authority and the LSC’s economic autonomy. Acting as a quasi-government agency, the LSC is obliged to carry out objectives like birth control, assisting disabled veterans, militia training, and funding public schools. A portion of its revenue is spent to provide such public services which are normally offered by the government. These expenditures will inevitably result in a reduced net income for the LSC and a minor increase in dividend distribution to its members.

There may be some confusion between the political and economic power in the LSC. Although the general meeting of member representatives is the ultimate decision-making body of the cooperative, a large proportion of the representatives are also CCP members. These representatives must simultaneously play the role of the peasants’ spokesperson and follow the CCP branch’s guidelines. Their dual status has often placed them in a delicate position. On the other hand, village authorities, with their privileged access to information, have the competence to initiate and coordinate economic activities and are de facto in a position to impose their choices on the cooperative in order to give priority to their own objectives.

According to the Shanglin LSC Charter, the cooperative must be democratically governed by its members, yet due to imperfect and asymmetric information, ordinary peasants lack effective means for monitoring the LSC’s operation. Though some villagers (shareholders) enter the board of directors through election, they have neither the experience nor the expertise for corporate leadership, but instead rely on village cadres to manage the LSC [

6]. What counts for villagers is only that the distributed profit increases every year. In practice, important decisions are usually made by a handful of people, often LSC executives and small private entrepreneurs in the community.

The LSC membership is not open to non-villagers: “village citizenship” is the entry criterion, as all the peasants in the village community collectively own the farmland and enjoy the land-use right through contract. To protect the integrity of the LSC’s asset, transfer of LSC shares on the market is currently prohibited. This situation hampers the normal population movement: villagers stay in the village so as not to lose their shares (and dividends). From the perspective of Game Theory, this form of organization has changed the nature of collective bargaining from a repeated game to a one-time game. If members are not satisfied with the choices, which are made on their behalf by their representatives in the LSC, they are not able to exit the cooperative or regain their land-use right. The vote with the feet evoked by Charles Tiebout [

29] does not work here.