1. Introduction

Recently, a number of cultural institutions such as museums, galleries, art auctions, events, and performance centers have utilized social network sites for promoting and marketing their culture, art content, and events [

1] Marketing activities of art organizations include exhibition, education, and collection and try to spread information via social network services (SNS). SNS is becoming an additional element in the promotion mix, in that it provides trustworthy information to lead users’ engagement with marketing activities [

2] The new term of “socialnomics” represents the prevalent influence of social networks on society, economics, politics, and culture [

3]

The online social space is appropriate for viral cultural products since users of SNS mainly share personal interests and spread hedonic consumption with close friends and acquaintances [

4]. If the viral content drives strong emotion such as joy, arousal, pleasure, sorrow, or horror, which are generally elicited from art products [

5], it will be carried to more and more people and with very rapid speed [

6,

7]. The strong emotion will make SNS users who have not frequently, or ever, consumed art products before get to know and be curious about them. As a result, they will intend to visit the gallery or museum as they are exposed to more and more information on art products and they share more and more information with others. However, there is a lack of research explaining how SNS fits for art product marketing and what type of motivation and trust exist before and after SNS use.

Before this study finds the effect of SNS on art institutions’ marketing activities, it needs to figure out why they use SNS in the first place. The motivation to engage in SNS is different from one institution to another and it will lead to different responses to the same information provided on social network sites. For instance, those who are willing to pursue fulfillment of their affective experience online will like, share, or post the art product information more actively. On the contrary, those who look only for information online will respond less to the emotional arousal that is frequently delivered by artistic content. If this study can verify the relationship, art institutions will be able to recognize who they should target and encourage to visit and consume their art content.

In addition, the degree of trust users will build from interaction with SNS will change their behavioral response. The more they trust the information on SNS, the more they will intend to visit and consume art products. The source of information will plays a critical role in how much trust users develop. Information from institutions or from meaningful others will have a different effect on trustworthiness. Certainly, this study is expected to fill the gaps of previous research and to find antecedents and postcedents in the process of SNS and art marketing. Finally, the result of this study is believed to give rise to greater utilization of art institutions’ SNS marketing in order to facilitate more public consumption.

Institutions, such as a museums, generally deliver history of art and culture to society and the community in order to reflect on previous achievements and to plan how culture will be sustained in the future. Sustainability is one of the most critical values in the management of a museum. The online social network service will have facilitated the communication between cultural heritage and citizens of the community. In this study, we will look closely the dynamics of institutional SNS and the intention to consume the cultural products when they have different motivation to use SNS.

Current research investigates the relationships between usage motivation for SNS and trustworthiness of the exhibition information provider or content, which is drawn from previous literature theorizing museums’ SNS utilization. Facebook’s page service is especially explored since it is the most representative SNS in the world and highlights relationship building between those who may be meaningful to one another. An online survey is employed in order to collect responses from actual participants of the Facebook page owned by a national museum of modern art. Further, the theoretical explanation of a hypothetical relationship among constructs and statistical results of data analysis is provided. Finally, the practical implications and direction of future research will be discussed.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Network Service in Art and Culture Domain

Recently, a growing number of museums and galleries are using SNS for marketing and as a communication channel for interaction with audiences. This results from the fact that SNS users are exploding throughout the world and the effect of the new communication vehicle is prevalent in every aspect of social activities.

The benefits of employing SNS in museums are represented in two ways. First, museums can expand the scope of contacts with present and future customers via SNS [

8]. SNS provides useful means to not only sustain strong ties with existing customers but also to reach out to those with weak ties because of geographical and social distance. That is, those having strong ties with museums could connect their acquaintances with the institution by sharing exhibition information through SNS. In addition, SNS may build up not only the relationship between museums and audiences but also relationships among audiences. Since museums are institutions that are supported by public users such as donators, contributors, volunteers, it is very important to maintain the relationship with them as long as possible [

9]. SNS would facilitate active and sustained participation of those key public users. Second, SNS will decrease the cost and increase the effectiveness of marketing activities. Those who have visited museums will share their experiences and opinions with people they know on SNS for free. If others perceive the information to be helpful and interesting, they will spread it over SNS and it will create the effect of word-of-mouth.

More and more museums and galleries over the world are using SNS to gain various advantages. According to Museum Analytics, museums in the U.S. and England employ Facebook and Twitter most actively and result in the largest number of “Likes” and “Followers.” Moreover, in 2012, around 90% of museums and galleries in the U.S. utilized SNS for promotion and marketing [

9]. This also happens in Asian countries including the Republic of Korea. For instance, the Korean National Museum of Modern Art opened a Facebook page in 2012 and the number of “Likes” has since increased ten times over, as of 2014. In Seoul, 22 out of 34 galleries (64%) have Facebook institutional pages and 15 provide multiple fan pages through Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and Flickr, in addition to Facebook.

2.2. Motivation to Use SNS

According to the uses and gratifications theory of social psychology, individuals use media in order to fulfill their various needs and motivations [

10]. This perspective can be applied to the service environment of SNS based on voluntary participation of audiences [

11]. The motivation of SNS users critically influences the way they diffuse or accept information via SNS [

12]. That is, users will be more interested in the information that fits their motivation to use SNS.

Previous literature suggests various motivations for SNS use. They provided a framework for explaining SNS use with utilitarian, hedonic, or self-expressional motivation [

13,

14]. Leung and Wei [

15] showed that the main motivations of Facebook use are informational, such as search and share for event information, and relational motivation to be connected with others.

Present research categorizes motivations of SNS users into two groups: informational and relational motivation. Informational motivation includes information acquisition [

14], content sharing [

16,

17], information provision [

8], information searching [

18], and expert searching [

19]. Relational motivation includes conversation and connection [

16,

17], social relationship building [

14], opinion sharing [

20], communication [

19], relationships [

21], expansion of offline relationships [

22], and sustaining relationships [

18].

2.3. Art and Culture as Experiential Products

Experiential products are known to provide joy and flow while one consumes the products or service, to place value on the process itself [

23], and they commonly involve art and cultural products and services. The value of experiential goods is difficult to assess before actually experiencing the product or the service, since the information on those goods cannot be acquired indirectly, contrary to search goods [

24].

In SNS, sharing the vivid experiences of others who had consumed previously experiential goods such as an art exhibition would fill the gap between indirect information and actual experiences [

25]. This will give potential consumers self-confidence, which will be sufficient to make the decision to visit or purchase the art and culture products by decreasing ambiguity. Trustworthiness of the information source will play a critical role in the middle of opinion sharing and determination to purchase experiential goods. If one knows that the information is provided by an institutional page in an SNS and one trusts the institution very much, the information on the art exhibition will offer a greater chance for one to visit the exhibition in the very near future.

This study postulates that there are two types of information providers that will variate the level of trust: museums with high trustworthiness and individuals who are well acquainted with them.

2.4. Trust in Information Provider

Trust has been researched in management, psychology, marketing, and philosophy for decades. Trust is known to be multi-dimensional and is defined as the perceived belief that information provided is factual, realistic, and believable [

26]. Trust in the information provider and the content itself is a critical component in SNS interaction. In general, an online transaction with another has lower trust than that of an offline transaction since it cannot replace the offline environment completely [

27]. However, the recent online environment of self-exposure increases social telepresense, and hence, elicits more and more social support [

27]. A study reports that increased social telepresense of online news also increases trust [

28]. According to the persuasion-knowledge theory, in the case of critical information, the trustworthiness, satisfaction, and intention to act based on the information all increased when it is provided by an expert, contrary to a layman. However, the relationship is reversed when information involved is non-critical [

29]. We might expect that when one has social motivation to use SNS, one could trust information provided from close friends more than from socially distant experts or institutions.

2.5. Word-of-Mouth

Word-of-mouth has become one of the important factors affecting consumption before actual purchase or experience [

30,

31] since it influences consumers’ cognition, expectation, and attitude on products [

32]. Previous research explains that meeting consumers’ expectations generates successful word-of-mouth [

33,

34]. Opinions or reviews of experiential products are transferred from the person who consumed them before to those who have never consumed them before [

35]. Emerging new media platforms, including SNS, increase the chances of word-of-mouth among consumers [

26]. Especially, the lack of information on experiential products such as art exhibitions has been lessened and abundant information on images, videos, and reviews gives audiences information very close to the real experience, which has never been provided before [

36].

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Informational Motivation and Trust on the Institution

Those who have informational motivation explore information in shorter timeframes and in more formal, intentional, and utilitarian ways than others. In addition, the more they trust the information provider, the more they value the information provided [

37]. Well-renowned art museums authorized by national institutions are assessed as trustworthy; as a result, they are assumed to provide trustful, rational, and objective information. Therefore, information users of SNS will be hypothesized to trust information provided by an authorized institution more than that provided by friends.

Hypothesis 1a. SNS users with informational motivation will trust information provided by authorized institutions.

Hypothesis 1b. SNS users with informational motivation will show more trust with information provided by institutions than with information provided by friends.

3.2. Relational Motivation and Turst on Friends

While the amount of information provided from the online environment has been increasing and the time and effort to find necessary information from it has also been increasing, online consumers are willing to behave based on recommendations or opinions given by those who share the same interests [

35].

Especially, those who use SNS for relational motives, with which they develop social relationships and share their opinions, will consider the social influence developed when they share their opinions [

35]. In addition, if the person who experienced the product before is a close friend or is one who belongs to the same community, the information provided will have more credibility and reliability, and hence, it will have a more positive influence on decision-making [

38,

39]. Therefore, people who are more relationship-oriented would favour information provided by friends who belong to the same communities more than information provided by an institution such as museum, which is not considered to belong to the same communities. The following hypothesis explains different level of trustworthiness:

Hypothesis 2a. SNS users with relational motivation will trust information provided by friends.

Hypothesis 2b. SNS users with relational motivation will show more trust with information provided by friends than with information provided by an authorized institution.

3.3. Trust in the Institution and the SNS Information

Trust in information is determined by trust in the information provider and the content itself [

40]. For instance, trust in a job candidate represented on a social network site positively influences the information content itself on the site [

41]. Therefore, we hypothesized that trust in information providers such as institutions or friends will positively affect trust in content itself.

Hypothesis 3a. Trust in the institutions and the information provided from the institutions will have a positive impact on trust in SNS information itself.

Hypothesis 3b. Trust in friends and the information provided from the friends will have a positive impact on trust in SNS information itself.

3.4. Trust and WoM of Information Provider and Contents

Previous research on communications has validated that the source or content of information has a critical impact on consumers who acquire the information [

42]. For example, if hotel visitors are satisfied with and trust hotel services, there is a high likelihood that they will revisit the hotel [

43]. Therefore, we hypothesized that trust in institutions and the content of information provided from institutions and, similarly, friends and the content of information provided from friends, will have a positive impact on word-of-mouth for the corresponding information.

Hypothesis 4a. Trust in the institutions will have a positive impact on word-of-mouth of the corresponding information.

Hypothesis 4b. Trust in friends will have a positive impact on word-of-mouth for the corresponding information.

Hypothesis 4c. Trust in the SNS information will have a positive impact on word-of-mouth for the corresponding information.

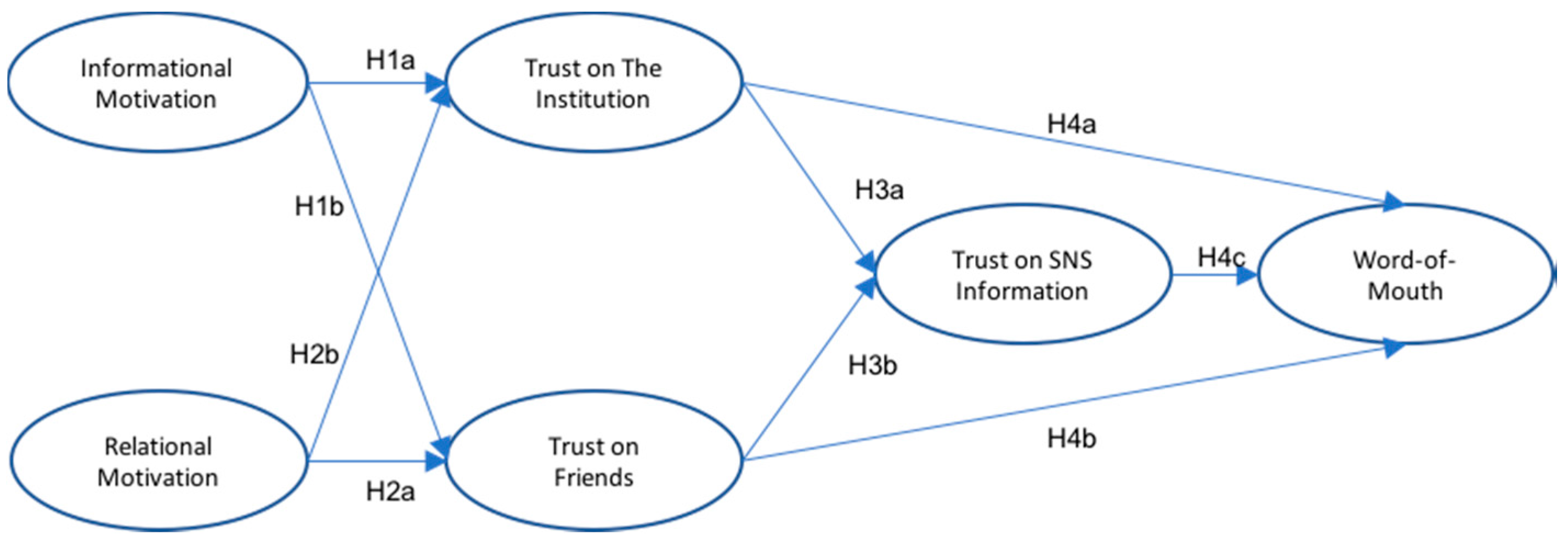

Research model of the current research is in

Figure 1.

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample

To verify the hypotheses of this study, an online survey was conducted with Facebook users who have seen postings that contain art content at least once. As such, the users who have “Liked” the Facebook page managed by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, as well as users who have “Liked” one of the eight art content posts from this page, were surveyed. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art is a leading museum in the Republic of Korea. It is sufficiently representative of the entire group because the Facebook page operated by this museum actively posts content and has the highest number of “Likes” among all of the domestic museums, with 70,009 “Likes” as of 25 November, 2014. The Google Docs survey was sent to 13 friends among 70,009 people who have pressed “Like” on the Facebook page of the museum and 1300 people among 4072 people in total who have pressed “Like” on the eight art-content-related postings by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. The survey was sent via Facebook message, and 156 people answered the survey. Among these, two insincere participants were excluded, and ultimately, 154 responses were utilized in the analysis, and incentives were provided to the respondants.

4.2. Measurement

The measurement items for the motivation of practical SNS use were taken and modified from the items that Voss et al. [

44] utilized in their study, and five items were used. The social motivation of SNS use measurement items were taken from the items in the studies by Lin and Lu [

45], Kwon and Wen [

46], and Wu [

47] and were modified to suit the needs of this study, totaling five items. The reliability of the information provided by the institution or friends and the reliability of the content thus gathered were measured using the items from the study by Bart et al. [

48], modified to be appropriate for this study. For the word-of-mouth effect, three items were utilized, modified from the items used by Wu [

47]. This study has used a 7-point Likert scale (Not quite so—1 point, Very much so—7 points) to measure all variables, and the measurement items are shown in

Appendix A (

Table A1).

5. Result

The variables used to analyze the demographic characteristics of the sample, including sex, age, education level, monthly income, residential area, familiarity with culture and arts, and degree of Facebook use, and the analysis results can be found in

Table 1.

In terms of sex, there were 116 women (75.3%) and 38 men. The majority of the participants were 20–30 years of age (90%). With reference to the Social Network Usage Analysis reported by the Korea Information Society Development Institute in December 2013, the majority of social network users are 10–30 years of age; therefore, the sample is representative of all SNS users. The education level was focused on university (attending/graduate) level education with 110 participants (71.4%), and 70 participants (45.5%) had a monthly income of less than KRW 1 million. The majority of the participants resided in either Seoul (58.4%) or the Gyeonggi Province (31.2%).

In terms of familiarity with culture and arts, 105 participants (68.2%) visited museums less than once a month, 80 participants were culture or arts professionals (51.9%) with jobs related to culture or arts, and 74 participants were not (48.1%). The participants were going to museums mostly alone (51.3%) or with colleagues and friends (37.3%).

In terms of Facebook usage, 50 participants (32.5%) visited Facebook two or three times a day, 58 participants (37.7%) visited Facebook more than four times a day, 74 participants (48.1%) used Facebook for less than 30 min a day, and 44 participants (28.6%) used Facebook from 30 to 60 min a day. The clear majority of people—126 participants (81.9%)—had been on Facebook for between one and five years, and the participants utilized Facebook to read postings (66.9%).

Regarding the number of times that exhibit information postings were viewed, 24 participants (15.6%) viewed them less than once a month, 27 participants (17.5%) viewed them 2–3 times a month, 27 participants (17.5%) viewed them 1–2 times a week, 17 participants (11%) viewed them 3–6 times a week, 18 participants (11.7%) viewed them once a day, 32 participants (20.8%) viewed them 2–3 times a day, and 9 participants (5.8%) viewed them more than 4 times a day.

5.1. Measurement Validity & Reliability

To analyze the reliability of measurement items, this study has calculated the Cronbach’s α values. Cronbach’s α values are normally viewed as acceptable if they are over 0.6 [

49]. The goals for SNS use used in this study, informational, relational, reliability of the institution and information provided by the institution, reliability of friends and information provided by the friends, reliability of the exhibit information, and word-of-mouth effect variables, had respective values of 0.93, 0.91, 0.95, 0.96, 0.96, and 0.91 and thus one can see that they are highly reliable.

Next, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted using the AMOS 18.0 program on the measurement model containing all six measurement variables to measure the goodness of fit. This resulted in a goodness of fit index that did not match the standard. For ideal goodness of fit and simplicity, modification indices were examined, and as such, items 1–5 in the relational SNS use, items 12 and 5 of the reliability of the institution and the exhibit information provided by the institution, item 2 in the reliability of friends and the exhibit information provided by the friends, and item 5 in the reliability of the exhibit information content were deleted. Moreover, items 1, 2, 4, and 5 of the informational SNS use, and items 1 and 2 in the reliability of the institution and the exhibit information provided by the institution were correlated. After nine items were deleted and six were correlated, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted again, with results shown in

Table 2.

The goodness of fit indices were found to be Χ

2 = 446.767 (d.f. = 281,

p = 0.000), CFI = 0.962, RMSEA = 0.062, and as this generally meets the criteria for goodness of fit from Hair et al. [

50] (pp. 752–753) (CFI of more than 0.95, RMSEA less than 0.08,

p-value of Χ

2 is sensitive to sample size and measurement variables), the measurement model of this study is appropriate.

All standardized factor loadings for the measurement items of measurement variables were statistically significant, and the values are shown in

Table 2 (

t > 6.00). Moreover, construct reliability and the average variance extracted values were calculated to evaluate convergent validity. The reliability of the usage motivations, informational, relational, institution reliability, friends reliability, exhibit information content reliability, and the word-of-mouth effect were respectively 0.86, 0.82, 0.91, 0.93, 0.94, and 0.85 and the average variance extracted values were respectively 0.72, 0.65, 0.82, 0.84, 0.85, and 0.77. As shown in

Table 2, all values are in line with the normal standard suggested by Hair et al. [

50] (pp. 776–778) (reliability > 0.70, AVE > 0.50), and the convergent validity standard for the measurement items belonging to the measurement variables is met.

Lastly, in order to evaluate discriminant validity, the squared values of AVE and correlation coefficients were compared. If the squared values of the correlation coefficients of two measurement variables are smaller than the AVE of each measurement variable, discriminant validity between the two measurement variables is thought to be present [

51]. As a result, squared correlation coefficient values were calculated for six measurement variables according to the correlation values suggested in

Table 3, and the largest value thereof is 0.57 (Exhibit information content reliability and word-of-mouth effect) and is smaller than the smallest value of the AVE, which is 0.65 (relational SNS use). Therefore, the six measurement variables have discriminant validity.

5.2. Hypotheses Testing

The structural equation model utilized to verify the hypothesis set in this study was analyzed using AMOS 18.0. First, the modification indices were examined, and to improve the reliability index, item 3 of the informational measurement variable was deleted, and items 7 and 8 of the relational measurement variable were correlated. The analysis of the results were Χ

2 = 447.898 (d.f. = 261,

p = 0.000), CFI = 0.955, RMSEA = 0.068, and met the criteria suggested by Hair et al. [

50]. The verification results of the hypothesis set are shown in

Table 4.

First, hypothesis 1a predicts that users with informational motivation for SNS use rely on the exhibit information provided by the institution and on the institution itself. The standardized path coefficient was 0.38 (t = 3.27, p < 0.01), and the hypothesis was supported. In addition, users with informational motivation for SNS use relied on friends and the exhibit information provided by friends. The standardized path coefficient was 0.33 (t = 3.07, p < 0.01), which was statistically significant. Hypothesis 1b predicts that users with informational motivation for SNS use rely more on information provided by institutions than information provided by friends. The standardized path coefficient of informational motivation onto trust on friends, 0.33 (t = 3.07, p < 0.01) was compared to that of 0.38 from Hypothesis 1a by t-test of the difference (t = 0.33, p > 0.10), which was not statistically significant, and the hypothesis H1b was not supported.

Second, hypothesis 2a predicts that users with relational motivation for SNS use rely on friends and the exhibit information provided by friends. The standardized path coefficient was 0.30 (t = 2.77, p < 0.01), and the hypothesis was supported. For hypothesis 2b, users with relational motivation for SNS use do not rely on the exhibition information provided by the institution and the institution itself. The standardized path coefficient was 0.15 (t = 1.33, p > 0.10), which was not statistically significant. Therefore Hypothesis 2b was supported with the fact that users with relational motivation rely more on information provided by friends than information provided by institutions.

Third, hypothesis 3a predicts that the reliability of the institution and the exhibit information provided by the institution will influence the reliability of exhibit information content. The standardized path coefficient was 0.33 (t = 4.87, p < 0.001), and the hypothesis was supported. Hypothesis 3b predicts that the reliability of the friends and the exhibit information provided by the friends will influence the reliability of exhibit information content. The standardized path coefficient was 0.56 (t = 7.92, p < 0.001), and the hypothesis was supported.

Fourth, hypothesis 4a predicts that the reliability of the institution and the exhibit information provided by the institution will influence the word-of-mouth effect of the exhibit information. The standardized path coefficient was 0.21 (

t = 3.07,

p < 0.05), and the hypothesis was supported. Hypothesis 4b predicts that the reliability of the friends and the exhibit information provided by the friends will influence the word-of-mouth effect of the exhibit information. The standardized path coefficient was 0.28 (

t = 3.43,

p < 0.001), and the hypothesis was supported. Hypothesis 4c predicts that the reliability of exhibit information content will influence the word-of-mouth effect of the exhibit information. The standardized path coefficient was 0.44 (

t = 4.81,

p < 0.001), and the hypothesis was supported.

Figure 2 shows the results of the path analysis.

6. Conclusions

This study has classified key characteristics of an SNS into information gathering and relationship forming categories. By considering the informational and relational motivations of SNS use, this study has examined the reliability of exhibit information on Facebook, among the SNS, and SNS influence on the museum’s word-of-mouth effect.

The analysis of the study model can be summarized as follows. First, the users with informational motivation for SNS use had a meaningful influence on the reliability of the exhibit information provided by the institution and the institution itself. This indicates that the informational users who utilize social network services in practical manners such as information gathering and sharing perceive the museum as a trustworthy institution, and believe that the official exhibit information from the museum is reliable. On the other hand, the informational users who utilize social network services do meaningfully influence the reliability of their friends and the exhibit information from friends. This seems to result from the primary motivations for using SNS for informational users, which are practical information gathering and sharing, and thus they believe that the exhibit information provided by both institutions and friends is reliable.

Secondly, relational SNS users’ perceptions of reliability were found to be meaningfully influenced by their friends, but their perceptions were not influenced by the reliability of the institution or the exhibit information provided by the institution. So, users who utilize SNS for social use, such as relationship advancements and sharing opinions, value the social influence from the people with whom they share interests and therefore believe that the information from their friends is reliable; they do not regard the exhibit information from institutions as being reliable.

Third, the reliability of the institutions and the exhibit information provided by the institutions and the reliability of the friends and the exhibit information provided by the friends have a meaningful influence on the reliability of exhibit information content. This matches with the results of the study by Wesselink [

41]. This indicates that the reliability of the trust and dependability of the exhibit information provider is an important factor that leads to relying on the exhibit information content.

Fourth, the reliability of the institution and the exhibit information provided by the institutions, the reliability of the friends and the exhibit information provided by the friends, and the reliability on the exhibit information content have a meaningful influence on the word-of-mouth effect on the exhibit information. This matches with the results of the study by Kim et al. [

52]. It seems that the informational factors such as the exhibit information providers and the exhibit information content have positive influences on the people receiving or reading information; this also indicates that the reliability of the institution and the exhibit information provided by the institutions, the reliability of the friends and the exhibit information provided by the friends, and the reliability on the exhibit information provided are important factors that have a positive influence on the word-of-mouth effect on exhibit information.

7. Discussion

The theoretical considerations of this study are as follows. Consumption is mainly divided into utilitarian consumption and hedonic consumption, and this study is significant because it has examined the exhibit information of museums as hedonic consumption in its spread throughout SNS. Moreover, the majority of consumption of culture and arts, such as museum exhibitions, has a strong hedonic intent and requires dynamic participation from the viewers; this study has suggested considerations for museum SNS use by applying the emotional and cognitive aspects of SNS and the ability to form consensus. These results could be applied in other areas of hedonic nature related to culture and arts, and not only museums.

The practical considerations of this study are as follows. This study is significant because it suggests marketing strategies that match the needs and the motivation of consumers for museums utilizing SNS. Based on the results of this study, museums can utilize SNS to reach out to viewers with strong previous connections and also to the public with weak connections or no connections at all, and stimulate frequent public consumption for the exhibits held at the museums. Therefore, it is easier for the public to fulfill the need to enjoy culture and arts.

The limitations of this study and future study directions are as follows.

First, the target for the online survey was limited to the users who utilize the Facebook page of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. The National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art is a leading national museum that represents the Republic of Korea, and already has a basic foundation of trust with the general public. This study has utilized a survey that targets users who “Liked” the Facebook page of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, and the exhibit information posted by this page, and frequent users of this Facebook page may already trust the reliability of the exhibit information provided by the institution. Therefore, future studies should confirm the results of this study by targeting users of Facebook pages of private museums and galleries.

Second, this study has utilized a survey that targets users who “Liked” the exhibit information posted by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art on its Facebook page. As museums have a diverse range of educational programs and events for adults and children, not simply exhibitions, so if the content of the information were classified and users who “Liked” different postings were surveyed, the results could differ. For example, the user who “Liked” a post relating to an entertaining event is likely to be a user who is responsive to the entertainment aspect of the SNS. As such, the motivation for SNS use could also include entertainment as a motivation, and further studies could be done for entertainment-motivated users to determine if they are positively responsive to entertainment events rather than other information.

Third, the sample size of the survey used in this study is 154; this is relatively small to represent the entire population. Future studies should gather a larger sample that not only includes Facebook users, but also users of other SNS such as Twitter or Flickr, to achieve more reliable study results.

The impact of institutional SNS will not only contribute to the communication and marketing for the audiences but also to direct sales and revenues. National museums and private galleries are both pursuing higher revenues by means of selling cultural product or experiences. The products are differentiated from utilitarian products which are consumed upon purchase. Culture and art products are so affective and experiential that the consumption is transferred to others through viral communication. Therefore, SNS is much more influential for experiential products such as culture and art, than for material products. As shown by the result of the current study, SNS has a significant impact on the viral deployment of exhibition information that is meditated by trust for the information provider. The differentiated trust that is dependent on the source of the information and the resulting behaviors based on it will play a critical role in building new services and systems for various institutions providing culture and art experiences.