Social Sustainability in an Ageing Chinese Society: Towards an Integrative Conceptual Framework

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review on Social Sustainability

3. Conceptual Framework of Social Sustainability

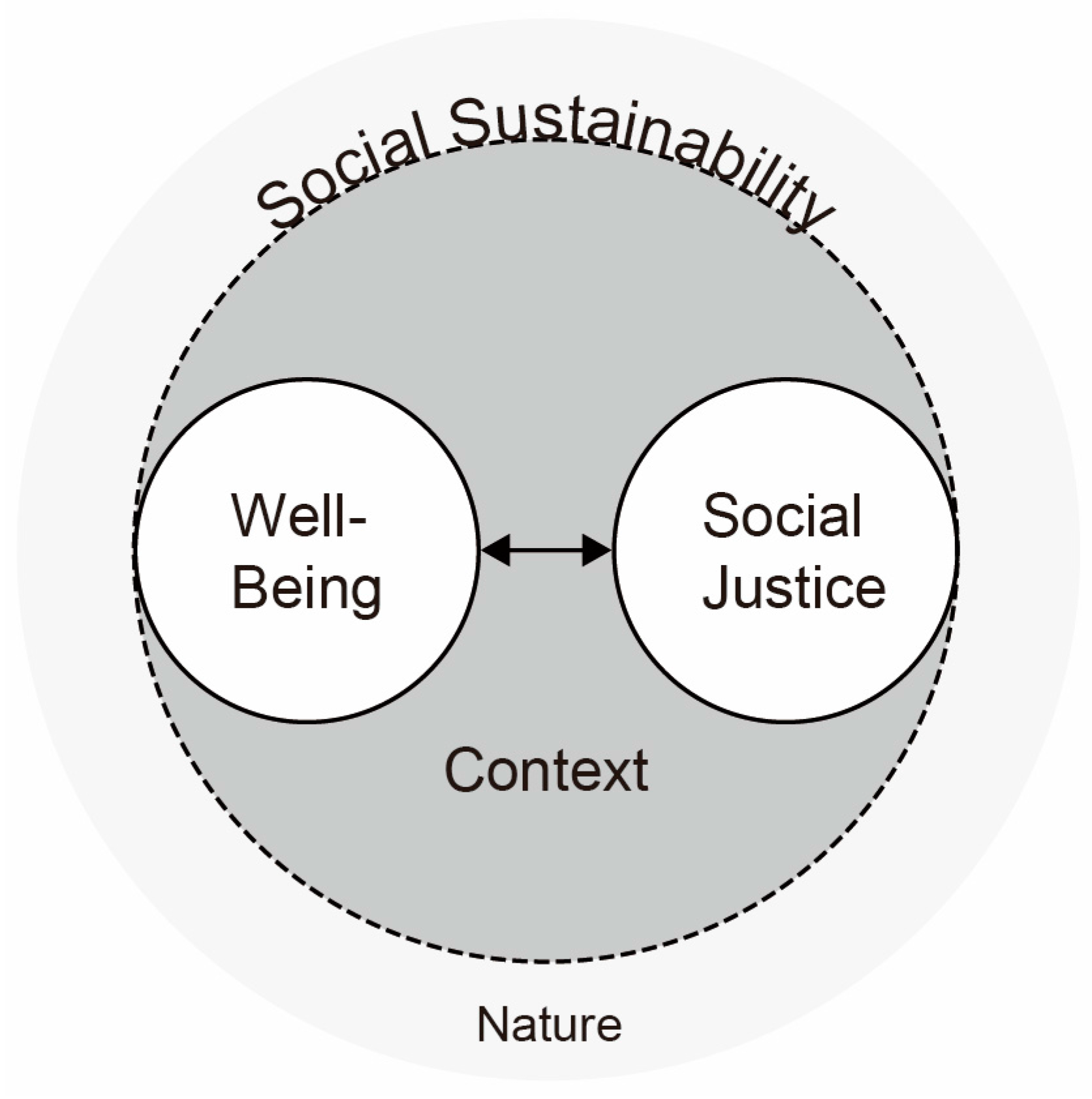

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Contextualization of Well-Being

3.3. Contextualization of Social Justice

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Littig, B.; Griessler, E. Social sustainability: A catchword between political pragmatism and social theory. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, M.A. Missing pillar? Challenges in theorizing and practicing social sustainability: Introductory article in the special issue. Sustainability 2012, 8, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åhman, H. Social sustainability-society at the intersection of development and maintenance. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A. Social sustainability: A review and critique of traditional versus emerging themes and assessment methods. In Proceedings of the Sue-Mot Conference 2009: Second International Conference on Whole Life Urban Sustainability and Its Assessment, Loughborough, UK, 22–24 April 2009; Horner, M., Price, A., Bebbington, J., Emmanuel, R., Eds.; SUE-MoT: Dundee, UK, 2009; pp. 865–885. [Google Scholar]

- Cuthill, M. Strengthening the ‘social’ in sustainable development: Developing a conceptual framework for social sustainability in a rapid urban growth region in Australia. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 8, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Colantonio, A. Urban Regeneration & Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, D.; Lee, S.W.S. Does culture influence what and how we think? Effects of priming individualism and collectivism. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 311–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D.A. China’s New Confucianism: Politics and Everyday Life in a Changing Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Geertman, S. Toward smart governance and social sustainability for Chinese migrant communities. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The framework of social sustainability for Chinese communities: Revelation from western experiences. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 2, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dijst, M.; Geertman, S. Residential segregation and well-being inequality between local and migrant elderly in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzakis, E.; Moro, M. The poor, the rich and the happy: Exploring the link between income and subjective well-being. J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steverink, N.; Lindenberg, S.; Ormel, J. Towards understanding successful ageing: Patterned change in resources and goals. Ageing Soc. 1998, 18, 441–467. [Google Scholar]

- Banister, J.; Bloom, D.; Rosenberg, L. Population aging and economic growth in China. In The Chinese Economy: A New Transition; Aoki, M., Wu, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 114–149. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Powell, J.L. Aging in China: Implications to Social Policy of a Changing Economic State; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Dijst, M.; Geertman, S. Residential segregation and well-being inequality over time: A study on the local and migrant elderly people in Shanghai. Cities 2015, 49, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute Working Paper Series, No. 27; University of South Australia: Adelaide, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcraft, S. Social sustainability and new communities: Moving from concept to practice in the UK. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 68, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, O.; Hedgcock, D. Urban social sustainability: The planning of an Australian city. Cities 1993, 10, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, I. Social sustainability and whole development: Exploring the dimensions of sustainable development. In Sustainability and the Social Sciences; Becker, E., Jahn, T., Eds.; Zed Books: Paris, France, 1999; pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M. Urban policy engagement with social sustainability in metro Vancouver. Urban. Studies 2012, 49, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dave, S. Neighbourhood density and social sustainability in cities of developing countries. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T.; Ganser, R.; Carpenter, J.; Ngombe, A. Measuring Socially Sustainable Urban Regeneration in Europe; EIB Final Report; Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development (OISD): Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ghahramanpouri, A.; Lamit, H.; Sedaghatnia, S. Urban social sustainability trends in research literature. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R. Social justice: Rawlsian or Confucian? In Comparative Approaches to Chinese Philosophy; Mou, B., Ed.; Ashgate Publishing: Hampshire, UK, 2003; pp. 144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Inoguchi, T.; Shin, D.C. The quality of life in Confucian Asia: From physical welfare to subjective well-being. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 92, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Chan, A.C.M. Filial piety and psychological well-being in well older Chinese. J. Gerontol.-Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2006, 61, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R. Confucian filial piety and long term care for aged parents. HEC Forum 2006, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, L.G.; Lynch, S.M. The pursuit of happiness in China: Individualism, collectivism, and subjective well-being during China’s economic and social transformation. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 114, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y. Spatial access to health services in Shanghai. In Proceedings of the Cities Health and Well-being, Urban Age Conference, Hong Kong, China, 16–17 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W. Sources of migrant housing disadvantage in urban China. Environ. Plan. A 2004, 36, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Helne, T.; Hirvilammi, T. Wellbeing and sustainability: A relational approach. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, D.S.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Antons, D.C.; Munoz, P.; Bai, X.; Fragkias, M.; Gutscher, H. A vision for human well-being: Transition to social sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. In The Science of Well-Being; Diener, E., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ormel, J.; Lindenberg, S.; Steverink, N.; Verbrugge, L.M. Subjective well-being and social production functions. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 61–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Ryan, K. Subjective well-being: A general overview. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2009, 39, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettema, D.; Gärling, T.; Olsson, L.E.; Friman, M. Out-of-home activities, daily travel, and subjective well-being. Transp. Res. Part. A Policy Pract. 2010, 44, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasper, D. Subjective and objective well-being in relation to economic inputs: Puzzles and responses. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2005, 63, 177–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E. Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Soc. Indic. Res. 1997, 40, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.; Mollenkopf, H. International and multi-disciplinary perspectives on quality of life in old age: Conceptual issues. In Quality of Life in Old Age; Mollenkopf, H., Walker, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, S. Continuities in the theory of social production functions. In Verklarende Sociologie: Opstellen Voor Reinhard Wippler; Ganzeboom, H., Lindenberg, S., Eds.; Thela Thesis: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nieboer, A.; Lindenberg, S.; Boomsma, A.; van Bruggen, A.C. Dimensions of well-being and their measurement: The Spf-Il scale. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 73, 313–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bruggen, A. Individual Production of Social Well-being: An Exploratory Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, S. Intrinsic motivation in a new light. Kyklos 2001, 54, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. Residential patterns of parents and their married children in contemporary China: A life course approach. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2005, 24, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Chinese conceptions of justice and reward allocation. In Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding People in Context; Kim, U., Yang, K.S., Hwang, K.K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. The cultural relativity of the quality of life concept. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Nevis, E.C. Using an American perspective in understanding another culture: Toward a hierarchy of needs for the People’s Republic of China. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1983, 19, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambrel, P.A.; Cianci, R. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: Does it apply in a collectivist culture. J. Appl. Manag. Entrep. 2003, 8, 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Gilmour, R. Cultural and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB. J. Happiness Stud. 2004, 5, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckhausen, J.; Wrosch, C.; Schulz, R. A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 32–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steverink, N.; Lindenberg, S. Which social needs are important for subjective well-being? What happens to them with aging? Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steverink, N.; Lindenberg, S.; Slaets, J.P.J. How to understand and improve older people’s self-management of wellbeing. Eur. J. Ageing 2005, 2, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Jenson, J.; Saint-Martin, D. New routes to social cohesion? Citizenship and the social investment state. Can. J. Soc./Cah. Can. Soc. 2003, 28, 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, A.; Pijl, M.; Ungerson, C.; Anttonen, A. Payments for Care: A Comparative Overview; Avebury: Aldershot, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Arts, W.; Gelissen, J. Welfare states, solidarity and justice principles: Does the type really matter? Acta Soc. 2001, 44, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, G. Welfare regimes and social stratification. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2015, 25, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringen, S.; Ngok, K. What kind of welfare state is emerging in China? In Towards Universal Health Care in Emerging Economies; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Meindl, J.R.; Hunt, R.G.; Cheng, Y.K. Justice on the road to change in the people’s republic of China. Soc. Justice Res. 1994, 7, 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, M.; Rowley, C. Chinese management at the crossroads: Setting the scene. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2010, 16, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Institution and inequality: The hukou system in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2005, 33, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Bian, Y.; Bian, F. Housing inequality in Urban China in the 1990s. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 1999, 23, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.R.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Access to housing in urban China. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 914–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.W.; Buckingham, W. Is China abolishing the hukou system? China Q. 2008, 195, 582–606. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, A.; Schmitt, C.; Kuhnle, S. Towards a Chinese welfare state? Tagging the concept of social Security in China. In Proceedings of the 6th ISSA International Policy and Research Conference on Social Security: Emerging Trends in Times of Instability: New Challenges and Opportunities for Social Security, Luxembourg, 29 September–1 October 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.; Geertman, S.; Hooimeijer, P. Access to homeownership in urban China: A comparison between skilled migrants and skilled locals in Nanjing. Cities 2016, 50, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, L. Housing inequality in transitional Beijing. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 936–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W. Migrant settlement and spatial distribution in metropolitan Shanghai. Prof. Geogr. 2008, 60, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Li, Z. Sociospatial differentiation: Processes and spaces in subdistricts of Shanghai. Urban Geogr. 2005, 26, 137–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Key Themes of Social Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|

| Needs Satisfaction & Well-Being Related | Social Justice & Equity Related | |

| Littig and Griessler [1] | Satisfaction of basic needs and quality of life; social coherence. | Social justice. |

| Dempsey et al. [7] | Sustainable community. | Social equity. |

| Dave [26] | Amount of living space; health of the inhabitants; community spirit and social interaction; sense of safety; satisfaction with the neighborhood. | Equal access to facilities and amenities. |

| Cuthill [6] | Social capital; social infrastructure. | Social justice and equity; Engaged governance. |

| Holden [25] | Inclusion; adaptability; security. | Equity. |

| Åhman [4] | Basic needs; education; quality of life; social capital; social cohesion, integration, and diversity; sense of place. | Equity. |

| Top Level Universal Goals | Subjective Well-Being | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Well-Being | Social Well-Being | ||||

| First-order instrumental goals/Basic needs | Comfort (physiological needs; pleasant and safe environment) | Stimulation (optimal level of arousal) | Status (control over scarce resources) | Behavioral confirmation (approval for ‘doing the right things’) | Affection (positive inputs from caring others) |

| Activities (examples) | Eating; drinking; resting; using appliances; securing housing and clothing; self-care | Physically and mentally arousing activities; sports; study; creative activities; active recreation | Paid work; consumption; excelling in a valued dimension | Behaving according to external and internal norms (compliance) | Exchanging emotional support; spending time together |

| Resources and endowments (examples) | Financial means; food; housing; physical health | Physical and mental health; financial means | Education; social origin; scarce capabilities | Social skills; social network; normative environment | Attractiveness; empathy; intimate ties; partner; children |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Dijst, M.; Geertman, S.; Cui, C. Social Sustainability in an Ageing Chinese Society: Towards an Integrative Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040658

Liu Y, Dijst M, Geertman S, Cui C. Social Sustainability in an Ageing Chinese Society: Towards an Integrative Conceptual Framework. Sustainability. 2017; 9(4):658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040658

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yafei, Martin Dijst, Stan Geertman, and Can Cui. 2017. "Social Sustainability in an Ageing Chinese Society: Towards an Integrative Conceptual Framework" Sustainability 9, no. 4: 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040658