1. Introduction

Start-ups, among other enterprises, can play a role in the development and commercialization of new technologies and the development of national economies, given that firms are the innovation

locus for the entire society [

1,

2,

3].

Well aware of the role that start-ups as well as other innovative firms could play within the economic system, many countries have recently been adopting ambitious intervention programs aimed at strengthening and modernizing their innovation ecosystems [

4]. Indeed, it is important to point out that the term innovation cannot be only traced back to technological progress, but also to social and/or cultural development.

Italy, in particular, has adopted measures aimed at fostering the establishment and development of innovative startups by promoting a renewed approach towards public support of entrepreneurship among start-ups. In particular, the attention devoted to these firms by the Italian government for the first time is based on the assumption that start-ups are important for promoting sustainable growth, technological development, employment (youth employment in particular) and other social aspects [

5].

Based on this assumption, a specific regulation regarding these firms has been issued, of which the aims are: (1) to develop an environment able to foster the creation of entrepreneurial opportunities, innovation, and social mobility; (2) to strengthen the links between universities and businesses; and (3) to attract investments and talented people to Italy from abroad [

6].

Innovative start-ups were defined by the Italian government as “any companies with shared capital (i.e., limited companies) including cooperatives, whose capital shares—or equivalent—are neither listed on a regulated market nor on a multilateral negotiation system.” [

7] (p. 7).

Moreover, innovative start-ups must also meet the following requirements:

at least 15% of the company’s expenses must be devoted to R&D activities;

at least 1/3 of the total workforce must be PhD students, holders of a PhD or researchers; alternatively, 2/3 of the total workforce must hold a Master’s degree; and

the enterprise must be holder, depository or licensee of a registered patent (industrial property) or the owner of a program for original registered computers (Art. 25, comma 2 of the Law Decree no. 179/2012).

Among innovative start-ups, those with a social vocation are of particular interest because they operate in a social context. Through innovative activities and/or initiatives, they produce extensive and long-term effects as potential benefits or changes in the community with regard to knowledge, attitudes, state, living conditions, and values [

8,

9].

However, the literature does not include studies about start-ups or other innovative firms, using the social innovation lens.

Moreover, innovative start-ups (see

Section 2.1) have not yet been studied especially when assessing their sustainability orientation and/or approach. Such start-ups have not yet been studied in the only country in which they have been regulated by law. Only a recently published paper looks at start-ups, not innovative ones, and at their orientation to sustainability, trying to understand if it is rewarded by investors [

10]. Finally, few works in the literature explore the link between social innovation and sustainability and only some of them investigate their reciprocal links i.e., social innovation and CSR (i.e., [

11]) or social innovation and the social aspect of sustainability (i.e., [

12]). Indeed, the relationship between social innovation and the three specific pillars of sustainability have not yet been analyzed simultaneously in the New Technology-Based Enterprise domain and especially not in innovative start-ups.

Therefore, the aim of this paper is to focus on Italian innovative start-ups with a social vocation and to investigate the relationship between social innovation and all sustainability aspects as well as their interplay as perceived by these firms. This paper will also focus on trying to understand how sustainability could be fostered through the start-ups and their technological innovations.

The resulting research questions can be formulated as follows:

Do innovative start-ups with a social vocation put in place actions and/or activities that align with one or more aspects of sustainability?

Are innovative start-ups aware of the links among the three pillars of sustainability and do they take full advantage of their interplay for their business?

Do social innovation actions and/or initiatives impact sustainability as a whole?

This work will contribute to start filling the existing gaps in the literature already highlighted on social innovation, sustainability, and innovative start-ups providing greater management for achieving the goal of sustainability.

After outlining the aim of the paper, this contribution starts with some essential insights to clearly identify the domain of our study, i.e., start-ups, distinguishing them for other innovative enterprises. It then outlines some essential insights about social innovation and sustainability before focusing on their interplay as studied by management scholars.

Then, the methodology used to perform the content analysis on the Social Impact Assessment Documents, provided by the Italian innovative start-ups of the selected sample, will be outlined and the results will follow. The paper ends with a discussion of the results and the conclusion will encompass contributions, both theoretical and managerial implications, limitations of the study, and future avenues of research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. New Technology-Based Firms, Technology Entrepreneurship and Innovative Start-Ups: Some Evidence from the Literature

According to Schumpeter, the most important function of entrepreneurs is to reform or to reinvent the pattern of value generation by exploiting inventions. The new economic context characterized by globalization, knowledge, the increasing role of innovation in regional innovation systems and the importance of technological entrepreneurship as a factor in wealth creation, generates the emergence of new types of entrepreneurial ecosystems [

13,

14,

15].

Some regions are more developed than others, due to success in using new technologies and attention in fostering technological entrepreneurship.

In the firm context, it is possible to find different kinds of enterprises focusing on innovation in a broad sense, which are quite different from each other. Therefore, it is important to identify them and frame them correctly.

Among them, the most studied in the literature are: New Technology-Based Firms, firms based on Technology entrepreneurship and Start-ups. These terms, therefore, cannot be considered synonyms.

A New Technology-Based Firm (NTBF) is a company that uses scientific and technological knowledge systematically and continuously to produce new goods and/or services with high added value. It is based on the exploitation of an invention and/or technological innovation, it also employs a high percentage of qualified employees. NTBFs almost always operate in top-level strategic sectors, such as microelectronics, biotechnology, medical devices, nanotechnology, etc. and they perform in-house R&D or develop R&D in close cooperation with universities and research centers.

The term NTBFs seems to have been coined by Little [

16].

In 1977, this author realized a path-breaking report comparing NTBFs in the United States with those in the UK and West Germany.

Little [

16] defined an NTBF as a firm having the following characteristics:

- −

It must have been established within the last 25 years.

- −

It must be a business based on a potential invention or with substantial technological risks.

- −

It must have been established by a group of individuals, and so must not be a subsidiary of an established company.

- −

It must have been established with the purpose of exploiting an invention or technological innovation.

In 1994, the European Commission also focused on these firms by commissioning a study deemed to understand the economic importance of New Technology-Based Firms in Europe [

3].

Besides the above-mentioned definition, other definitions and/or problems in assessing it have emerged over time.

The first one simply refers to their name—“New Technology-Based Firm”—in that it is not clear whether “new” applies to the firm, or to the technology, or to both.

For example, Shearman and Burrell [

17] argue that the term NTBF should be restricted to refer only to new independent enterprises that are developing new industries. In their study, they focused on the development of the medical laser industry as a classic example of where NTBFs can more easily be found. This industry is new and the firms within it are newly established and independent of each other. Almost by definition, they are small in number and in size [

18].

Butchart [

19] defines the NTBF industry “as a sector that has significantly higher than average expenditure on R&D as a proportion of sales or significantly greater than average proportional employment of workers who are qualified scientists and engineers” [

18] (p. 5).

Storey [

3] affirms that an extensive definition of NTBFs would embrace all new firms operating in “high technology” sectors. However, the definition of “high technology” proposed is in itself problematic. Shearman and Burrell [

18], for example, consider the latter as “high tech SMEs”, therefore distinguishing them from NTBFs.

Apart from the definition, still not agreed upon among authors, various studies focus on the contribution that NTBFs have made to employment, technological innovation and new technological knowledge [

20].

Some authors argue that NTBFs are just a small percentage of firms, so their contribution to employment and national technological performance is marginal [

21,

22].

On the contrary, other scholars suggest that NTBFs are really important, as they can be considered the primary source of new employment and the engine for both technological change and economic growth [

23].

Firms based on Technology entrepreneurship are somewhat different from NTBFs.

Technology entrepreneurship is a multi-dimensional concept that involves a variety of actors and different levels of analysis [

24].

Over time, various definitions have been proposed for this term.

Dorf and Byers [

25] define technological entrepreneurship as a style of business leadership that involves identification and human resource high-potential capitalization, technology intensive commercial opportunities, management of accelerated growth and significant risk taking.

Again, Shane and Venkataraman [

26] see technological entrepreneurship as the processes of assembling resources, technical systems and strategies through an entrepreneurial venture to pursue opportunities.

Analyzing a study conducted by Bailetti [

27] (p. 9) through a review of the literature, six definitions of technology entrepreneurship were found:

- 1

organization, management, and risk bearing of a technology based business [

28];

- 2

solutions in search of problems [

29]);

- 3

establishment of a new technology venture [

30];

- 4

ways in which entrepreneurs draw on resources and structures to exploit emerging technology opportunities [

31];

- 5

joint efforts to interpret ambiguous data, joint understanding to sustain technology efforts, and persistent, coordinated endeavor to accomplish technological change [

32]; and

- 6

an agency that is distributed among different kinds of actors, each of whom becomes involved with a technology and, in the process, generates inputs that result in the transformation of an emerging technological path [

24].

Based on his research, Bialetti defines “Technology entrepreneurship [as] an investment in a project that assembles and deploys specialized individuals and heterogeneous assets that are intricately related to advances in scientific and technological knowledge for the purpose of creating and capturing value for a firm” [

27] (p. 9).

In addition, Roja [

33] affirms that “one of the most important component of technology entrepreneurship ecosystem is the entrepreneur itself, and he is the key catalyst in the process of business sectors emergence and start-ups growth. Technology entrepreneurs have more technical skills and competences than non-technical ones, for example business skills”.

Comparing the definitions of NTBF and technology entrepreneurship it is possible to state that the two concepts are different. Technological entrepreneurship indeed emphasizes the technological skills, capacities, abilities of the entrepreneur as well as his style of leadership and the various kinds of role actors can play in supporting it in the broad domain of innovation, also to create a new technological venture or exploit emerging technological opportunities (see above).

Start-ups, on the other hand, differ from the above two kinds of firms.

Even if various definitions of start-up can be found in the literature, a “start-up” can be understood as a new company with a strong dose of innovation and is configured to grow rapidly according to a scalable and repeatable business model [

34].

There are two fundamental characteristics that a start-up must have: characteristics that are scalable and repeatable.

Scalable means that a business can increase its size and complexity in an exponential way, while having a repeatable business model means that the start-up has developed a business model which can be replicated, with only small changes if needed, in different places and at different times [

34].

Innovative start-ups can show this feature—to be innovative—in terms of the developed business model and/or in the high level of innovation encompassed in its products and/or services. Indeed, the term innovative start-up was first used only for high-tech firms operating only on the Web or being digital in a broad sense. Only later, the term was extended to new innovative companies operating in other industries such as manufacturing.

Recently, also the so-called innovative born-global have been included in the innovative start-up definition. These are defined as firms that “seek […] to derive significant competitive advantage from the use of resources and the sales of outputs in multiple countries” [

35] (p. 49).

These firms can actually be considered innovative start-ups because, as some authors point out [

36,

37,

38], they are small technology-oriented companies that also share a vision and strategy to become global and/or international.

Looking at the above-mentioned definitions, it is clear that the firms considered in each definition differ from each other, sometimes greatly.

The point of contact is represented by technology, but this must be understood in a different way when speaking about NTBFs, start-ups, etc. For example, an innovative start-up can use already existent technology in a different industry and/or in a different way thanks to a new business model, a NTBF, for example, has developed but then discovers that it is far from its core business and is therefore not so appealing to be exploited.

Comparing Italian innovative start-ups (the focus of our study) with NTBFs, it is possible to point out that there are some common traits in their definitions, even if Italian innovative start-ups are a category per se because a regulation has defined them with this term. For example, Little [

16] states that NTBF “[…] must have been established by a group of individuals and so must not be a subsidiary of an established company”. This aspect is also mentioned in the Italian legislation of innovative start-ups “[…] they are not constituted by merger, company spin-off or following sale of company or branch of company” (D.L. 179/2012 art. 25 comma 1 point g).

Moreover, innovative start-ups do not necessarily have to realize high-tech products or use high technologies; they must simply fulfill the requirements established by law. Therefore, only a small percentage of them can be considered really technological.

Therefore, the concept of innovation expressed by legislation is broad and includes other aspects, not strictly technological ones. The purpose of this broad definition is to bring benefits to many entrepreneurs, helping many sectors of the economy (crafts, social, commercial or agricultural) and promoting social and cultural development [

5].

Thus, it is important to affirm that many innovative start-ups cannot be considered NTBFs or the result of technology entrepreneurship. Indeed, also the results of this study carried out on Italian innovative start-ups show that almost all firms have not developed technological products and/or services; some of them just use already existent technologies in different ways, especially in the service industry.

2.2. Social Innovation and Sustainability: A New Field of Research

The term social innovation has become a common phrase in recent years. Some analysts consider social innovation no more than a buzz word or a passing fad that is too vague to be usefully and effectively applied to academic scholarship while other scholars associate a significant value to social innovation since it identifies a critical type of innovation [

8].

The EU Commission defines Social Innovations as “[…] Innovations that are both social in their ends and in their means. Social Innovations are new ideas (products, services and models) that simultaneously meet social needs (more effectively than alternatives) and create new social relationships or collaborations” [

9].

Innovative activities and services must be motivated by the aim of meeting a social need and should be predominantly developed and diffused through organizations. Therefore, social innovation is different from business innovation, which is generally motivated by profit maximization without any social impact [

8].

The concept of social innovation is quite broad and refers to many economic aspects such as: institutional [

38], social purposes [

39], public goods [

40] and also needs not yet taken into account by private markets [

41].

Consequently, the goals of social innovation are many and varied.

First, social innovation aims at producing long lasting outcomes that are relevant for society based on the needs and challenges society must face and manage. In doing so, it is necessary to look beyond technological innovations and focus on how social innovations can contribute to important public values (e.g., health, education, safety, and life quality) [

42,

43,

44].

Moreover, social innovation aims at changing social relationships and the “playing rules” between involved stakeholders. For example, social innovation aims to get citizens involved in decision making and to actively participate in managing social issues [

10]. In this context, it is essential that stakeholders are involved, not only in the design, but also in the implementation and/or adoption of an innovation. In this sense, social innovation also refers to the idea of participation and collaboration [

45,

46,

47].

To date, social innovation, as a recent stream of literature, has been studied under different profiles: seeking to define it [

48,

49], using the policy lens [

50,

51], focusing on governance aspects [

52] or management issues [

53], and looking at different sectors of services [

54,

55] or manufacturing [

56] or again adopting the lens of the social open innovation [

57,

58,

59].

There could be many cases of social innovation. For example, reintegration of women into uncomfortable situations with violence or disability, support platforms and educational content sharing, reduced food waste, reusing materials for end of life scenarios, city maintenance, apps for improving the lives of citizens, etc.

Therefore, New Technology-Based Enterprises, among them innovative start-ups, have never been studied under a social innovation lens. The link between social innovation and sustainability has also been understudied, which we will explain after a brief recall of essential sustainability insights.

The concept of sustainability was originally coined in forestry where it referred to never harvesting more than what the forest produced in new growth [

60]. This first definition of sustainability has evolved over time. Today sustainability is a central topic in social science studies as a whole. In particular, the major turning point was made with the Brundtland Report, which introduced the concept of sustainable development as a “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

61] (p. 41).

Sustainability has been studied under different profiles including: Organization (e.g., [

62]), business models [

63], project management [

64], supply chain management [

65,

66,

67], firm performance (e.g., [

68]) and strategic management (e.g., [

69]).

Since the Brundtland Report, the concept of sustainability has dramatically evolved and three essential and interrelated dimensions of it have emerged: social, economic, and environmental. These three dimensions have been defined as the pillars of sustainability which show that responsible development requires the simultaneous consideration of natural, human, and economic capital or a direct exchange between planet, people and profits [

70,

71,

72].

Indeed, it is possible to identify correlations and synergies between these three pillars and many of them have been discovered, acknowledged and/or investigated by scholars. For example, great environmental quality, scenic beauty, and biodiversity allow for regional economic income through sustainable tourism from which local communities may profit [

73]; sustainable construction allows for reduction in the use of nonrenewable energy resources and hence economic savings [

74], and the development of innovative technologies to generate power from renewable energy sources is broadly acknowledged as bearing the potential to generate workplaces and trigger economic growth while saving nonrenewable resources and reducing CO

2 emissions [

75] .

Among these papers, the study of Hansmann et al. [

76] focuses on the synergies between the three pillars of sustainability including an investigation of professional contributions to sustainability through principal component analysis. Using this methodology, authors managed to identify the best practices linked to each of the pillars of sustainability and then studied their interplay. Authors made the link between them clear by looking at well identified activities and practices.

Thanks to this particular approach, this study is also of interest to firms which, when seeking to achieve sustainability, can jointly develop the three areas of sustainability. Firms may use tailored activities and initiatives, but should not use general rules or guidelines.

Indeed, looking at the results of the paper, the social aspect of sustainability can be achieved thanks to:

Sustaining cultural and social values;

Protection of health;

Education and free personal development;

Solidarity between and within generations, as well as global;

Protection of safety; and

Juridical equality and certainty.

Looking at this list, it appears that most of these activities are also linked to “Life quality”, which is one of the characteristics literature links to the social aspect of sustainability [

40,

41,

42].

When the environmental aspect of sustainability is pursued, various initiatives can be put in place:

Protection of the natural environment;

Responsible use of renewable resources;

Reduction of the use of non-renewable resources;

Protection from environmental hazards, reduction of risks; and

Protection of natural spaces and biodiversity.

Finally, to achieve the economic aspect of sustainability, organizations should focus on:

Considering externalities in the market (cost reduction);

Generating income and employment;

Promoting the innovative power of the economy;

Enhancing social and human capital; and

Considering future generations for economic gains.

Despite this useful identification of activities needed to achieve sustainability, this classification has not been used in a firm context. Instead, this paper will use it as the basis of the content analysis performed on the Social Impact Assessment Document provided by innovative start-ups. This identification will not only help to show which aspects of sustainability are pursued but also how they are interrelated with each other. In fact, Hansmann et al. [

76] (p. 451) underlines that “Product and Process Development reflects how ecological innovation and modernization can generate social and economic benefits and at the same time facilitate the reduction in use of as well as the responsible use of natural resources”, “Education and Social Economics reflects how educational activities and sociocultural sustainability initiatives can simultaneously promote income and employment, social and human capital, and free personal development,” while “Protection of Nature and Humans covers the synergetic benefits which protection of natural spaces and biodiversity and the reduction of environmental risks have for the protection of health and safety of the population”.

Even if the literature on sustainability is well developed [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69], social innovation issues in this context represent a new stream of literature.

For instance, Osburg [

11] states that “Social Innovation is closer to the core Business of what is generally thought of and the key for companies to achieve Corporate Sustainability and thus meet the needs of triple bottom line reporting. It is not the new CSR and it offers huge potential for the future. The companies who will fully embrace Corporate Sustainability through driving Social Innovations will be the ones leading the next decades. We are only at the very beginning now” [

11] (p. 21).

Apart from this study linking social innovation only to corporate sustainability, another paper focuses on the link between social innovation and social sustainability, seeking to understand the role citizens and all other social actors play in developing sustainability. Even if social sustainability must not be confused with the social aspect of sustainability, this paper can help in looking at the link between sustainability, as we have already defined, and social innovation. In the latter it is stated that the dialogue between social innovation and social sustainability “calls attention to equity in the satisfaction of needs, to governance and social participation, as well as to processes of community learning and production of alternative knowledge for sustainability” assumes that “social innovation and social sustainability, as both conceptual constructs and social practices, are not only complementary: both are also mutually reinforcing in their ethical overlays and companions in procuring grounded answers to the question of how to carry out sustainability and in examining those social practices and local capacities leading to sustainable societal transformations [

12] (p. 147).”

Thanks to these contributions it is possible to gain some insights into the link between social innovation and sustainability. Based on the definition of social innovation and considering sustainability studies, social innovation as an innovative practice can be understood as the effective and sustainable application of a new product, service and/or business model having positive implications at a broader social level. Therefore, social innovation could also be considered as the natural outlet of actions undertaken to achieve sustainability as a whole or one of its aspects [

18].

Indeed, at the origins of social innovation processes are social pressures exerted by unsatisfied needs (e.g., proximity health services), wasted resources (e.g., soil consumption), environmental emergencies (e.g., air quality in inhabited centers) or social issues (e.g., growing areas of discomfort and marginality) [

77].

Consequently, the attention to sustainability issues can be considered an essential and typical component of social innovation projects and/or actions that distinguish it from the traditional practices of social assistance in that it creates a type of innovation (i.e., new services). Thus, firms willing to adopt social innovation naturally should be oriented to achieving sustainability as a whole or at least in one of its aspects.

However, it is clear that more contributions are needed regarding the link between social innovation and sustainability and especially for the three pillars of sustainability.

3. Materials and Methods

The selected methodology to perform this study is content analysis applied to social science.

According to Krippendorff [

78], the term content analysis appeared for the first time in the early 1940s in humanistic studies aimed at decoding messages contained in mass media. From a methodological point of view, research questions are answered through an inference process resulting from text analysis. Inference in content analysis is based on the logic of appropriation (as opposed to deduction and induction) so the responses that are obtained are not conclusive and have a degree of questionability [

78].

This methodology was chosen because it allows the researcher to investigate the selected subject and to highlight the issues important for the purpose of the study.

Due to the highly labor-intensive nature of data collection and analysis procedures, only a small number of companies can usually be investigated. For this reason, it is considered an ad hoc methodology for this study [

79].

According to Kracauer [

80], the methodology is based on a qualitative approach because quantitative orientation neglected the particular quality of texts. However, while in this study it is important to reconstruct contexts.

Indeed, to achieve the aim of the present paper, it is not useful to count and/or measure specific key words, but is fundamental to analyze and understand the essence of the content and the specifics of activities described by innovative start-ups. Moreover, the interpretation and role of the researcher is of fundamental importance. Bryman [

81] (p. 542) affirms that this approach to documents “emphasizes the role of the investigator in the construction of the meaning of and in texts. There is an emphasis on allowing categories to emerge out of data and on recognizing the significance for understanding the meaning of the context in which an item being analyzed (and the categories derived from it) appeared”.

Moreover, Italian innovative start-ups must prepare and publish on the start-up website and in the “Registro delle Imprese”—Chamber of Commerce—the Social Impact Assessment Document, which is a prepared document aimed at highlighting and measuring the social impact of their activities. This document describes the business activities and the medium-long term effect on the community, intended as potential benefits or changes, that the business generates in terms of knowledge, attitudes, status, living conditions, and values. At the same time, these results must be translated in measurable terms.

This particular document, given its aim, has been the basis for the content analysis performed in this paper.

Each Social Impact Assessment Document was analyzed using the activities and/or initiatives identified by Hansmann et al. [

76] since this is the only study retrieved from literature clearly identifying activities and/or initiatives put in place to achieve each of the pillars of sustainability and link them to each other.

Using the categories of the three aspects of sustainability identified by Hansmann et al. [

76] made it possible to check whether innovative start-ups with a social vocation are oriented towards sustainability and to identify recurring themes looking at their activities and/or initiatives.

The content analysis performed in this paper aimed at identifying and extracting activities and/or initiatives put in place by innovative start-ups and their most important and relevant features to check if they meet the categorization proposed by Hansmann et al. [

76]. The content analysis performed here was based on the theme/assertions [

78,

82] based on a thematic distinction that defines the context units of analysis [

78]. This choice has allowed the peculiarities of analyzed individual start-up cases to be appreciated; a result impossible to obtain choosing a rigid scheme for analysis based on keywords abstracted from their context.

Obviously, this method has a high degree of subjectivity [

79], which will be mentioned in the limitations of the paper. All innovative start-ups registered in the “Registro delle Imprese” that are part of the Innovative Start-up category of social innovation have been selected. This makes a total of 126 firms.

Looking at the industry to which they belong, two pertain to agriculture, eight to industry and handcraft, two are not included in any sector, and 114 fall into the service sector. We focus the analysis on the latter given their elevated number and base the decision on the fact that social innovation can be understood as the delivery of a service that benefits the community [

9].

Moreover, firms performing social innovation are mostly part of the services sector because the nature of social innovation places them naturally in this context [

83]. Based on a recent report on social innovation in Italy [

83], the activities carried out mainly fall within the scope of services and are mainly meant to disseminate social innovation through relational innovation, which is more achievable in the field of services. This same report considers that the aim of social innovation, which is to create an improvement for the community through innovation, is often easier to achieve in the context of services since they are more widely adopted by the community (e.g., the healthcare system, social assistance, etc.).

Only the innovative start-ups operating in the areas covered by legislation have been selected. Various provincial Chambers of Commerce have been subjectively included over time. Among the innovative start-ups, firms not operating in the industries identified by law were not considered since they do not make our sample homogeneous. The areas considered by law are: Publishing, Film Production, Video and Television Programs, Music and Sound Recordings, Scientific Research and Development, Education, Health Care, Residential and Non Residential Social Services, Creativity, Artistic and Creative Activities Entertainment, Library activities, Archives, Museums and other Cultural Activities, Sports Activities, and Entertainment.

Table 1 shows the specific activities carried out by companies in the service sector. The activities selected in bold in

Table 1 (73 start-ups) are the ones identified by law. They represent the sample for which the Social Impact Assessment Document was requested by the Chamber of Commerce to perform the content analysis.

Notwithstanding that it is compulsory for innovative start-ups to publish the Social Impact Assessment Document, only 61 of them were retrieved and therefore analyzed in this paper.

Regarding the geographical location of innovative start-ups, it can be said that most of them are located in Northern Italy (34 innovative start-ups, 56% of the sample), while 26% (16 start-ups) are in central Italy, and the rest (11 companies, 18% of the sample) are in Southern Italy.

This aspect highlights the differences of these regions in supporting the creation and development of start-ups. In fact, there are more development agencies, incubators, and entrepreneurship care centers in the north of Italy than in the rest of the country. This result is in line with the historical trend of business creation in Italy that sees Lombardy as the most active region. This shows that more attention is put on social innovation, as well as industrialism in general, by entrepreneurs operating in the north of Italy.

4. Results

The documents examined are very concise and describe, as required by law, the corporate mission, the social objective and the impact defined in measurable terms of activities and/or initiatives undertaken by innovative start-ups in the sustainability domain.

Each document was analyzed following the methodology described above and the overall results are presented in

Appendix A.

Before presenting the social aspects of sustainability results from the Social Impact Assessment Documents of innovative start-ups, it is worth mentioning the technology used by innovative start-ups to perform their social innovations.

The analysis showed that 28% of the entire sample (17 start-ups) set their activities through the use of digital platforms. This tool allows cohesion, sharing, and accessibility of the proposed services.

Platforms are most widely used in achieving social sustainability objectives like: life quality, cultural and social values, health protection, and education.

Indirectly, platforms also contribute to cost reduction, the development of new job opportunities, and, therefore, economic sustainability.

Only one innovative start-up exploits a patent and at the same time puts in place actions and/or initiatives deemed to achieve the three areas of sustainability. This is done to improve life quality by reducing the emission of polluting gases and the cost of healthcare for respiratory illnesses through the development of patented filters.

Finally, seven start-ups (11% of the entire sample) use multimedia apps to carry out their activities specifically for the goals of education, free personal development, and the development of cultural and social values. These are all themes falling within the social aspect of sustainability.

4.1. The Three Pillars of Sustainability in Innovative Start-Ups of the Sample

Only seven innovative start-ups out of 61 do not refer to any action and/or initiative aligning with the categorization made by Hansmann et al. [

48] in their Social Impact Assessment Document.

Considering all three aspects of sustainability and related activities and/or initiatives identified by Hansmann et al. [

76], 103 occurrences were counted, corresponding to 13 themes.

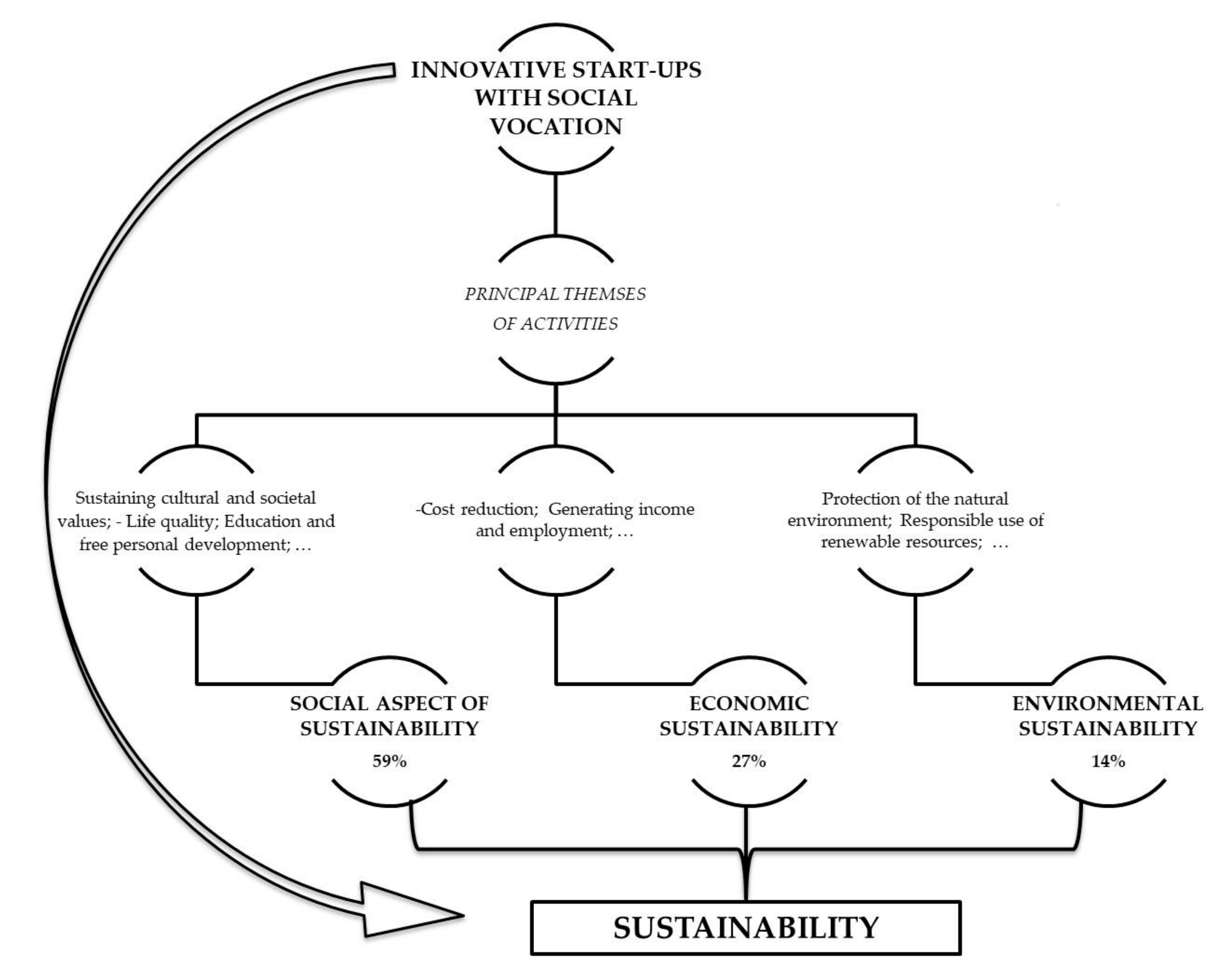

In particular, 61 occurrences (59%) fall in the social aspect of sustainability (52 start-ups), 28 (27%) are associated with economic sustainability (27 start-ups) and 14 (14%) are about environmental sustainability (12 start-ups) (see

Table 2). Some start-ups simultaneously have put in place more than one action and/or initiative, which is associated with different aspects of sustainability (see below for detailed results).

Source: Our elaboration.

There was a high number of innovative start-ups with social vocation meeting the social aspect of sustainability: 85% of the sample carried out some action and/or initiative linked to this first pillar of sustainability. Twenty-nine (56%) of the start-ups oriented to the social aspect of sustainability are located in Northern Italy, fourteen (27%) in the Center and nine (17%) in the South.

Those who carried out actions and/or initiatives in economic sustainability are 12 (44%) in the north, 11 (41%) in the center, and four (15%) in the south. Lastly, environmental sustainability-oriented startups are equally divided between Northern, Central, and Southern Italy.

These data confirm the above stated about the propensity of North Italy to have entrepreneurial development and implement various areas of sustainability.

Table 3 shows both the occurrences and the number of start-ups involved in the different themes, considering the number as well as the percentages. Columns 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively, have been created to clarify the different combinations of themes on which start-ups focused their efforts (see

Table 3).

Focusing on the detail of the activities and/or initiatives in

Table 3, it emerges that the main activities and/or initiatives of innovative start-ups tend to be sustaining cultural and social values with 34% of occurrences (18 start-ups involved), and attention to life quality which reaches 23% of occurrences among nine innovative start-ups.

The activities carried out by companies to sustain social and cultural values include: participation of citizens in public decisions and projects (through social crowdfunding campaigns, for example), definition of the best policies for a fairer distribution of public resources, protection and strengthening of cultural heritage (this is, in many cases, linked to education), strengthening multicultural integration and social cohesion (sometimes with the use of digital platforms).

The activities most commonly found in the life quality theme are: involving citizens in public management and decision making, improving the standard of living for disadvantaged citizens, improving access to public services, and increasing social resilience, the level of engagement of the population, and the level of social responsibility for businesses and local authorities.

No innovative start-up in the sample sustains both cultural and social values and pays attention to life quality.

A slightly lower number of innovative start-ups, in respect to the previously cited ones, support health protection goals and educational development. For both, 11 occurrences were retrieved (18% of the sample, respectively, Number 7 and 6 innovative start-ups) and among them none carry out actions and/or initiatives in both domains.

Moreover, three innovative start-ups sustaining cultural and social values are also devoted to carrying out actions and/or initiatives deemed to educate and to sustain free personal development. In this case, educational activities were aimed at children to help develop personal skills oriented to the culture of well-being, respect, environmental sustainability, or initiatives about the need to reinvent cities while respecting all social categories.

Five start-ups are devoted to life quality and not carrying out actions and/or initiatives to sustain cultural and social values. The start-ups also undertake actions and/or initiatives in the health protection domain (i.e., activities and/or initiatives to improve the independence of people with dementia and improve the standard of living or to act with ad hoc disposition on harmful gas emissions to reduce respiratory illness).

Moreover, one innovative start-up prefers to focus on education, free personal development, and safety (through safe and structured access to Internet and television content by children that also provides an Internet and television accessibility service content with high educational values).

Finally, we can observe how none of the innovative start-ups focus simultaneously on the three themes of the social aspect of sustainability (life, protection of health, and education).

With regard to health, most innovative start-ups work to intervene in learning disabilities and in the management of disabled people and supporting their families while start-ups focusing on education and free personal development mostly develop activities and/or initiatives such as sharing and improving personal talents; promoting sensitivity and empathy in the experiences of others; and encouraging the interest and involvement of students in volunteering. Start-ups focused on education also strive to develop social skills such as solidarity, mutual help, support, empathy; or select and propose Internet and television accessibility service with high educational values.

The two occurrences found for solidarity between and within generations and globally, refers to two start-ups which promote activities and/or initiatives creating a network of institutions, agencies, and services accessible to migrant people as well as easy access for financial advisory services among disadvantaged people.

The two innovative start-ups involved in protection of safety promote activities and/or initiatives like creating safe and structured access to Internet or television content for children and create highly technological products for preventing maltreatment of women and children.

The theme of juridical equality and certainty has not been found in the sample of innovative start-ups analyzed.

While Hansmann et al. [

76] consider it within the social aspects of sustainability, Parra [

19], for example, considers equity and justice as two terms qualifying social sustainability, which must not be confused with the social aspect of sustainability (see above).

Table 4 shows the results for economic sustainability.

Examining economic sustainability, the most highlighted activities and/or initiatives concern external market factors (15 innovative start-ups, 54% of the sample). This is especially true in terms of cost reduction and job market development. Indeed, the reduction of costs refers to the expenditure of the national healthcare system and its reduction due to business activities.

This objective, as stated above, is linked to social sustainability in health and life quality. In addition, ample space is dedicated to the creation of new employment opportunities (11 occurrences, 11 innovative start-ups, 39% of the start-up sample). One innovative start-up is simultaneously involved in generating income and employment as well as enhancing social and human capital. Specifically, through numerous industrial and product design activities, this innovative start-up aims to attract young and talented people by improving their skills and creating job and research opportunities for them.

No innovative start-up considers future generations with regard to economic aspects.

Results found for environmental sustainability themes are shown in

Table 5.

Table 5 shows that seven innovative start-ups (nine occurrences, 64% of the occurrences and 58% of the start-ups considered in the sample) develop their activities to protect the natural environment (e.g., environmental impact of structures, public awareness of eco-sustainability, and increased effectiveness and efficiency of choices for improving environmental sustainability conditions).

Regarding the responsible use of renewable resources (four occurrences, 29% of them), two innovative start-ups carry out activities and/or initiatives concerning the use of bio-materials, the recycling of materials, the development of a green and circular economy, and the promotion of clean energy production.

Two innovative start-ups simultaneously foster protection of the natural environment and a responsible use of renewable resources. No activities and/or initiatives have been found among the start-ups of the sample focusing on removing environmental hazards, reducing risks, and protecting natural spaces and biodiversity.

4.2. The Link between the Three Pillars of Sustainability in Innovative Start-Ups with a Social Vocation

Regarding the link between the three pillars of sustainability, among the total of selected innovative start-ups, 52 (85%) show the social aspect of sustainability, 27 (44%) show the aspect of economic sustainability, and 12 (20%) show environmental sustainability (Some of them show more than one aspect of sustainability—see below).

First, among the 52 innovative start-ups that develop simultaneously, 26 have some social aspect of sustainability, while 50% of them carry out some actions and/or initiatives to support economic sustainability.

A significant percentage of these start-ups (43% of the entire sample—26 out of 61) identifies a close link between the social aspect of sustainability and economic sustainability.

Indeed, it seems that innovative start-ups of the sample link activities and/or initiatives as sustaining cultural and social values, attention to life quality, protection of health and safety, education and solidarity (all themes pertaining to the social aspect of sustainability) to goals such as cost reduction and generation of employment, which are the most frequent themes supporting economic sustainability.

In this domain, the most recurrent tie is between life quality and the consideration of external factors in the market. Nine innovative start-ups out of 26 show this combination of activities and/or initiatives. Slightly less important is the relationship between the theme of health and the consideration of external factors in the market (eight innovative start-ups out of 26).

The theme of generating income and employment is linked to the feature of sustaining cultural and social values (five innovative start-ups) and education (three innovative start-ups).

Other links seem to be less important (sustaining cultural and social values and considering external factors in the market in two cases; promoting education and the innovative power of the economy in one case; solidarity and consideration of external factors in the market in only one innovative start-up and in the same way: education and generating income and employment, life quality, and generating income and employment).

Therefore, it is possible to affirm that economic sustainability is linked in some way to the social aspect of sustainability in the analyzed cases, but only among some themes. There may be a synergy between these two pillars: the attention to the social aspects of sustainability creates a good prospect for achieving a positive economic impact for the community, deliberately or in some cases involuntarily.

In fact, some of the innovative start-ups in the sample deliberate some actions and/or initiatives encompassed in the social aspect of sustainability, but without explicitly considering their economic repercussions. In these cases, while the social actions and/or initiatives meeting the social aspect of sustainability are clearly stated as goals of the start-up activity, the economic repercussions are revealed by their Social Impact Assessment Document. They foster economic sustainability, but innovative start-ups do not set them as goals, which reveals that perhaps they are not fully aware of the link between these two pillars of sustainability.

Considering the social aspect of sustainability, only 11 innovative start-ups (21% out of 52 or 18% out of 61 start-ups representing the entire sample) reveal a link between this pillar and environmental sustainability.

These two pillars seem to have a smaller link than the above one. In particular, there is a higher frequency among the initiatives and/or activities of sustaining cultural and social values and protecting the natural environment (three innovative start-ups). The most frequent activities performed by these innovative start-ups are: fusing the culture of environmental protection combined with social development or the creation of new eco-sustainable production models. These activities are also linked to the development of social and cultural values.

Moreover, for three innovative start-ups, the link between life quality and protection of the natural environment was found. The activities and/or initiatives carried out were: increasing social awareness of the risks and opportunities of its territory together with an increase of effectiveness and efficiency for actions that improve environmental sustainability conditions.

The connections between education and free personal development and protection of the natural environment emerged for two innovative start-ups; the same result was found for the combination between protection of health and responsible use of renewable resources.

As we can appreciate, the connection between the two issues is not very strong, but many of the activities undertaken share the desire to spread principles aimed at respecting the environment and social values.

It is possible to say that themes falling in the social aspect of sustainability often reflect and are similar to those needed for environmental sustainability (i.e., development of a culture based on well-being or attention and respect for the social context in which we live and the desire to improve it).

Regarding economic sustainability, only five innovative start-ups (17% out of 28 start-ups, 8% out of 61 representing the entire sample) simultaneously show the economic and the environmental aspects of sustainability.

The link most frequently found is between the responsible use of renewable resources and the consideration of external factors in the market (two innovative start-ups). Both start-ups focus on the use of renewable resources or low environmental impact products for the medical field. This generates a positive cost reduction for the national healthcare system.

This third link (economic sustainability and environmental sustainability) is more difficult to consider than the previously analyzed ones but also demonstrates that attention to the environment and environmental sustainability does not always involve a reduction in costs. In fact, the opposite often occurs. In this domain, Hansmann et al. [

76] (p. 458), for example, state that “achieving ecological aims in the present (e.g., through strict ecological regulations and conservation of natural resources) may have synergetic positive effects on the economic situation of future generations, even though it may hamper short-term economic growth” for the start-ups.

Moreover, the activities and/or initiatives performed to achieve these two pillars of sustainability are often not related. One example is the expansion of respect for the environment with a direct cost reduction in the healthcare system.

Finally, five companies (8% out of 61 start-ups falling in the sample) simultaneously present all three aspects of sustainability.

Two innovative start-ups simultaneously combined the themes of: protecting health, responsible use of renewable resources, and considering external factors in the market.

It is interesting to note that this link is confirmed by the literature. Indeed, Manika [

84] has applied “a holistic assessment of environmental CSR” in health protection. The study was carried out in a hospital and found that this positively affected the strategy of cost saving.

Based on the results, it is clear that some activities and/or initiatives of the innovative start-ups simultaneously permit safeguarding the health of the population and pay attention to the use of renewable resources. These combined activities entail an economic impact that often coincides with cost savings in the healthcare system.

Unfortunately, even if some other combinations of themes pertaining to the three aspects of sustainability can be found, these have been found only for single start-ups (e.g., life quality with responsible use of renewable resources and consideration of external factors in the market; sustaining cultural and societal values with responsible use of renewable resources and consideration of external market forces; sustaining cultural and societal values by protecting the natural environment and generating income and employment; cultural and societal values associated with reducing the use of non-renewable resources and generating income and employment, or enhancing social and human capital by reducing the use of non-renewable resources, and cultural and societal values).

This reveals that each social innovative start-up combining the three pillars of sustainability, other than the two previously cited, follows different paths and combines various actions and/or initiatives to reach its goals in the sustainability domain, consciously or otherwise (see above).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Performing content analysis on the Social Impact Assessment Document of innovative start-ups of the sample, it clearly emerges that many innovative start-ups put in place some actions and/or initiatives deemed to achieve one or more pillars of sustainability (see

Figure 1 for an overview).

Indeed, 89% of start-ups from the sample (54 out of 61) underlined at least one aspect of sustainability—only seven start-ups had none of the themes related to sustainability found in their Social Impact Assessment Document.

Therefore, the development of social innovation is mostly linked to the social aspects of sustainability. Indeed, only for this pillar can a really strong link be found between two themes, which are life quality and protection of health.

Moreover, social innovation, based on the social aspect of sustainability actions and/or initiatives, is frequently found in combination with economic sustainability themes. The analysis reveals that by achieving the social aspect, sustainability could result in the development of economic sustainability. Still, achieving social goals, such as life quality and health protection, have an impact on economic sustainability that can be identified. This may be in the form of cost savings.

Only a “soft” link emerged between the social aspect of sustainability and environmental sustainability while a conflict emerges between economic sustainability and environmental sustainability. The latter becomes more evident when trying to combine cost savings and bringing attention to the environment, which often requires more investment.

Consequently, it can be said that sustainability as a whole with its three pillars is not set as the sole goal of innovative start-ups of the sample. Many of the actions and/or initiatives started and carried out are consequences of the corporate mission while the link among them to adopt the sustainability lens is not the sole reason for their existence.

As a final remark, it can be said that the realization of social innovation is often based on sustainable actions and/or initiatives, but simultaneously fosters sustainability with actions and initiatives deemed to achieve one or more of its pillars. Sometimes these actions have wider effects on sustainability than those expected and/or pursued by innovative start-ups (see above, for example, the link between the social aspect of sustainability and economic sustainability). In this domain, a recent study states that: “Firm sustainability-oriented innovation also creates collective benefits; this type of innovation aims to: (1) reduce the negative effect, or enhance the positive effect, for collecting some business activities even beyond the levels established by regulations; (2) meet the individual needs of its target market with modes (products, services, delivery modes) which also generate a significant positive impact on the community; (3) to raise the environmental and social impact of the work of other economic entities (supply chain partners, distributors, end customers); (4) drive the progressive raising of reference standards towards which all operators must strive regarding social and environmental issues” (adapted from Reference [

83]).

Probably a greater awareness about social innovation impact could lead innovative start-ups to take full advantage of their actions and/or initiatives for sustainability and its pillar domains, strengthening their sustainability orientation.

From the theoretical point of view this work contributes to filling the existing gaps in literature already identified in social innovation, sustainability and innovative start-ups by seeking to broaden and deepen the debate on these interesting themes. However, further studies are needed since this paper only focuses on innovative start-ups with a social vocation operating in Italy.

From a managerial point of view, this research provides managerial implications for innovative start-ups oriented to sustainability. In particular, entrepreneurs could take into account the synergies and opportunities of social innovation in relation to sustainability, deepening and increasing the activities and/or initiatives geared to the three pillars of sustainability as well as highlighting sustainability orientation and achievements in business documents. Businesses making the link between the three pillars of sustainability clearer could assist with planning activities better and more wisely in this domain by remaining aware of all the pitfalls and, thereby, achieving their sustainability goals better and perhaps faster. Moreover, the brief technology overview carried out on innovative start-ups could serve as a suggestion for already existing firms and/or new entrepreneurs to fully understand how, for example, online platforms could enhance their business activities or how they could support their goals in terms of sustainability and/or social innovation, also through open innovation processes i.e., [

85,

86].

Some future avenues of research also present themselves.

It will be interesting in the future to use further research methodologies to cross with the results already achieved, such as formalizing interviews or questionnaires to better understand the entrepreneur’s orientation on the subject being addressed.

Furthermore, this study could be carried out considering not only innovative start-ups, but all New Technology-Based Enterprises in Italy, or all firms publishing a Social Balance Sheet, and study different clusters of them, seeking to understand whether there are significant differences among introduced actions based on operating sector and/or firm dimension etc. A further step could be made comparing results at different levels found in Italy, with the same levels in other European countries. Moreover, also social open innovation dynamics appear very appealing to be studied more in-depth, starting for example with a multiple-case study able to show how some firms have succeed in this domain.

This study also presents some limitations. The most important one is the subjectivity of the classification method used guided by the cognitive objective of the analysis. Additionally, based on the strong subjectivity of recruits made using the method, other problems emerge when considering the measurement issues (e.g., related to the calculation of the recurrence rates of keywords) and the deductions made by the researcher about the representation and interpretation of the results that emerge [

78]. Weber [

87], referring to the particular type of content analysis used in this paper, emphasizes that issues concerning classification, reliability of categories, and validity of coding operations as problematic.