1. Introduction

The criticism that general principles of sustainability and frameworks of strategic sustainable development have not stopped environmental crises and social conflicts highlights the need for practical outcomes for the scientific development of sustainability. Baumgartner [

1] states that despite the numerous definitions, models and initiatives that have been developed to make our societies more sustainable, the results from such efforts are dubious as to whether we have made ‘real’ progress toward more sustainable societies. Consequently, recent discussions on sustainability have led to new approaches that transcend the theoretical/normative perspective to include examinations of how sustainability can actually be practiced. Seeking to contribute to these sustainability studies, we use two theoretical streams—practice-based studies (PBS) on organisations and the institutional logic—to elaborate on the concept of sustainability as a practice.

Within sustainability studies, the idea of sustainability relating to institutional, organisational and individual practices has been elaborated upon in several recent discussions [

2,

3]. However, they adhere to a broad idea of practices instead of contextualising it within social theory. Since this practice turn in organisation studies [

4], many concepts belonging to the so-called ‘theories of practice’ have shed new light on understandings of how action and structure are intrinsically linked. Such a turn has introduced practice-based perspectives in other fields of management studies, such as organisational learning [

4], strategy [

5], and entrepreneurship [

6]. We argue that a practice-based approach to sustainability can fulfil a theoretical gap in sustainability studies: how the structures supporting the idea of sustainability within organisations can develop into the factual practice of sustainability. We assert that sustainability as a practice does not rely on the structures that support pro-sustainable actions on the operational-business level, or on the police-making level of productive sectors and governments. Sustainability relies on the practice of the agents in daily life, in the regular course of operations. Further, the performance of instrumental actions driven, for example, to meet the requirements of environmental and labour regulations or to fulfil governance concerns, must not be confused with the practice of sustainability. From a post structuralist approach on social practices, we assume that the unresolved problem of practicing sustainability relies on a new logic that will emerge when sustainability is not only about structures or instrumental actions, but it is about how both are intrinsically combined.

Post structuralism is an intellectual position that gained momentum in the social sciences in the 1970s [

7]. Its key assumption is that stress upon the primacy of the structure (i.e., structuralism) should be replaced by emphasis on practices that take place within the structure and that are constrained by it but that slowly change it from the inside out. Following this perspective, pursuing more sustainable societies requires an understanding of how sustainability is elaborated upon at the structural level of principles and frameworks that shape agent´s actions toward sustainability. Then, we must investigate how such actions come to be saturated with meanings elaborated upon by those involved in the day-to-day performance of sustainability. As practice does not occur automatically or in an unproblematic way [

8], understandings of sustainability as a practice must be highlighted, including what is required to achieve structural changes towards sustainability, analysing who is responsible for it and how they plan to implement it and determining how such changes manifest in practice.

From this point of view, leading social actors must intentionally aim to reduce the gap between structures and actions for sustainability by understanding the obstacles to the practice of sustainability and working to remove them. This has not yet happened because there are divergences regarding how to think about sustainability and how to translate it into practice [

2]. It is a challenge to manage the competing logics of sustainability that exist in the market [

9], which is why adopting IL as a theoretical approach may help to clarify how the idea of sustainability is negotiated and collectively elaborated via leading social actors serving as the institutional entrepreneurs who interact with other actors in and around organisations. Institutional logic (IL) is a socially constructed perspective [

10]. According to Thornton and Ocasio [

10] (p. 804), ILs are both material and symbolic—they provide the formal and informal rules of actions, interactions and interpretation that guide and constrain decision makers’.

With this in mind, we describe the idea of sustainability as a practice and define the Institutional Logic of Sustainability (ILS). In the literature, major institutions of society (e.g., market, family) often present contradictory logics [

10]. Hence, we argue that sustainability could be practiced in competition with other logics (e.g., commercial, growth) [

9,

11] or by assuming the position of a dominant logic [

12]. Following this perspective, we address the research gap regarding the comprehension of how sustainability can be a practice. While building theoretical contributions, we add to the sustainability literature by presenting an approach that fosters sustainable actions and stimulates a transition to sustainability [

8].

Our work creates possibilities for elaborating upon the relationship between practices and the new institutionalism, which is developed in the field of ‘strategy as a practice’ [

5,

13]. We examine previous literature on the subjects of sustainability, IL and PBS and reflect on the relationships among them. Overall, we describe an ILS that emerges from incorporating different actors’ cognitive structures and dispositions for action in the social contexts where sustainability is practiced.

2. Conceptual Building Theory

The effort we undertake in this paper can be described as theorisation. According to Weick [

14] regarding the possibilities of theory building, ‘what is not theory, theorizing is’; in other words, theorising is the process of developing theory. Our study uses a conceptual theory-building approach, mostly because it is an original yet introductory version of new theoretical articulations and constructs that may open up new avenues for future research [

15]. We agree with Lewin’s statement [

16] (p.169) that ‘there is nothing more practical than a good theory’. The arguments we use in defence of theorisation should be used to strengthen sustainability studies in order to create rigorous and complex theory in this field.

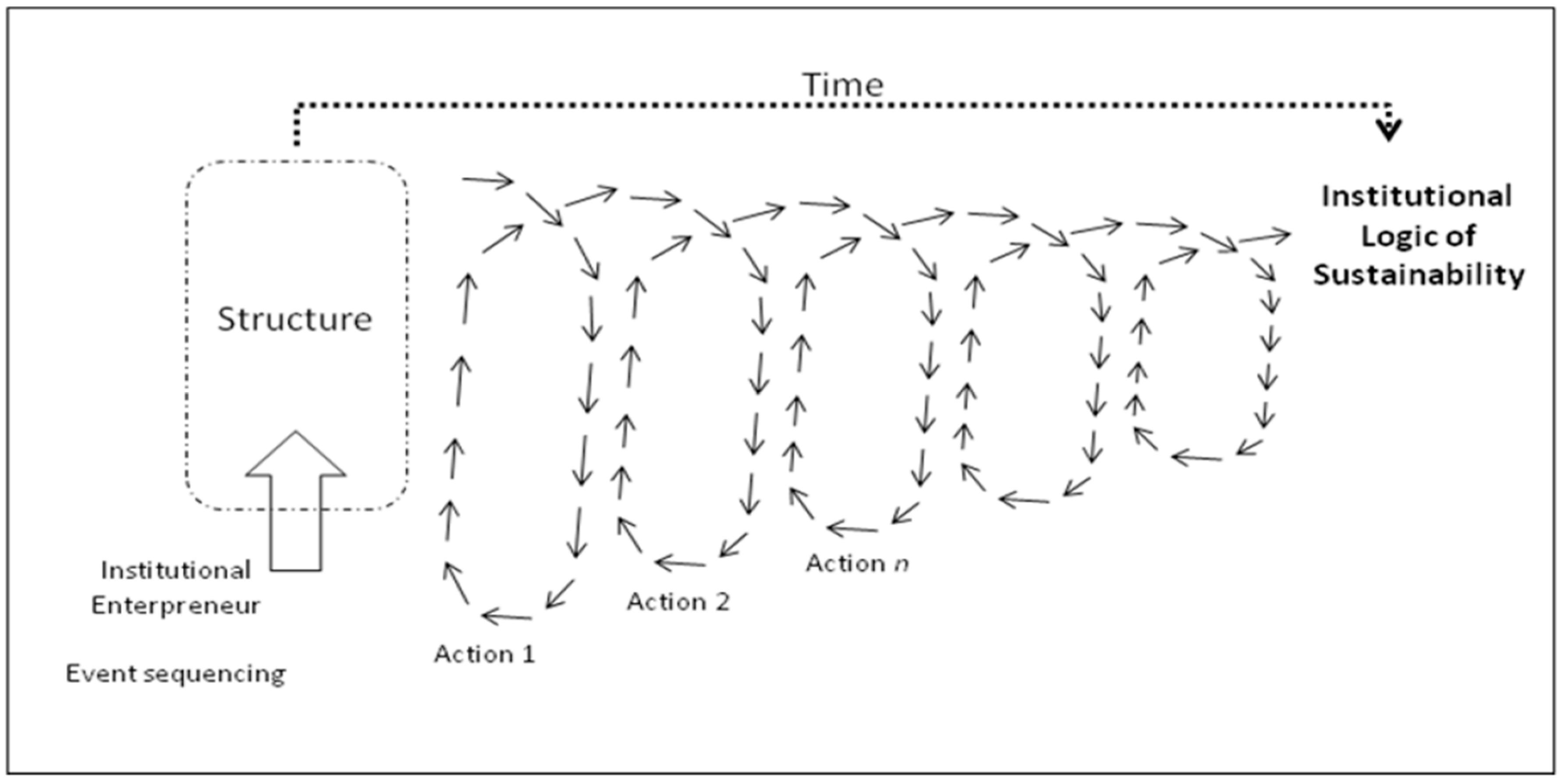

We propose that the factual practice of sustainability leads to the formation of an IL, namely the ILS. We argue that sustainability becoming a practice departs from a fixed yet permeable structure that shapes the idea of sustainability and objectifies the norms and theories that support it. Influenced by certain actors—most importantly institutional entrepreneurs—and through a sequence of events, the numerous actions that actors within organisations perform daily slowly converge to form a new logic: the ILS. This means that while agents’ discrete actions of sustainable behaviour gradually evolve into the practice of sustainability, the structural basis for their understanding is how sustainability changes into a new structure. The practice of sustainability becoming a new IL is depicted in

Figure 1. The following arguments seek to shed light on understandings of sustainability as a practice through four mechanisms of change: institutional entrepreneurship, structure overlap, event sequencing and the practice of sustainability.

As

Figure 1 shows, the basis for forming an ILS is the organisation’s immersion in a process of change, which is fundamental to studies of institutional analysis. However, through a sequence of events over time, sustainability as a practice becomes both the cause and the result of structural changes. It is influenced by events that can be sparked by one institutional entrepreneur who introduces new actions infused with sustainable values. The ILS arises from the legitimacy of these values and their incorporation into structures as sustainability becomes a practice. To stabilise an ILS, the practice of sustainability can be defined both as the starting point and at the result of several practices that stimulate a new logic.

The next sections present our theoretical approach to creating the arguments for the definitions as well as the ILS framework that we propose. First, we identify IL as the core of this proposal; here it is possible to demonstrate that a more internalised debate on sustainability studies would be useful, as it is not related to a result per se but includes some elements from a practice-based perspective. Second, we develop a debate about practices. Third, we present the main concepts of our framework: sustainability as practice and an ILS. The topics are complementary; thus, they can support the development of research into sustainability. To aid this, we detailed our framework comprising both theoretical perspectives. Fourth, we include discussions and conclusions about the elements to improve current sustainability literature.

3. The Institutional Logic Approach

Discussions of how the institutional perspective impacts the understanding of organisations have intensified in the last 40 years; thus, several approaches in the field of institutional analysis have emerged. According to Greenwood et al. [

17], institutional theory is one of the most common approaches to understanding organisations. Here, new institutionalism describes organisations that seek homogeneity from institutional isomorphism [

18]. However, not all actors subscribe to the same IL that guides the dynamics of interactions in an organisation. This is because IL is a collective identity that is socially constructed from institutionalised practices and behaviour [

19]. Thus, IL sheds new light on the institutional field and the formation of social structures.

The IL approach is rooted in the work of Friedland and Alford [

20]; they established the existence of a logic between institutions in society, which corroborated DiMaggio and Powell’s [

18] findings on neo-institutionalism. Institutions cannot be analysed in isolation from one another they must be understood as mutually dependent, although their relationships may be contradictory [

20]. According to Thornton et al. [

21], the precursors of IL theory claim that society is a marketplace made up of multiple institutional orders, and management can be understood from the perspective of individuals and organisations. IL is a theory that illustrates how culture influences organisational change, as the sequences of historical events reveal patterns that form the basis of cultural transformation [

22].

Thornton and Ocasio [

10] (p. 804) define institutional logic as ‘the socially constructed, historical pattern of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality’. Thus, certain typical characteristics facilitate an understanding of the process of change and the sharing of practices and behaviours. Some of these typical characteristics include economic systems, sources of identity, sources of legitimacy, sources of authority, bases of mission, bases of attention, bases of strategy, investment logic, governance mechanisms, institutional entrepreneurship, event sequencing and structure overlap [

22].

All of these aspects should be included in the definition of IL; however, most research on the subject has found that the last three aspects—institutional entrepreneurship, event sequencing and structure overlap (supported by the other previously mentioned aspects)—are sufficient for a clear understanding of IL [

19,

22]. This is because these three aspects include the others (such as bases of strategy and source of legitimacy, for example). Therefore, focusing on these three aspects supports the creation of identity in the field—that is, the formation of an IL.

We address processes of change based on institutional entrepreneurship, event sequencing and structure overlap [

21,

22]. These three factors and the other mechanisms of change are interconnected and influence each other in the development of IL. In order to understand this process, each factor must be examined individually; however, rather than broadly examining IL, we considers (in depth) the mechanisms that directly relate to sharing a vision—in this case, the practice of sustainability (see

Section 5). This is because, as a social value, sustainability can contribute to the formation of a collective identity, which is a basis for the development of IL. Thus, we do not analyse an ideal type, but instead we articulate an analytical argument in relation to the existing one.

According to Thornton et al. [

22], the IL of each sector of society interprets and forms a vision of the organisational structures that compose it. This idea relates to the perspective of industry, but this logic can also be applied to organisational fields. For Thornton et al. [

21], IL is the very representation of the organisational field, and it ratifies the notions of sharing and interaction. These notions may indicate the existence of a dynamic organisational field [

20] that includes interconnection and mutual influence. Thus, the two mechanisms—institutional entrepreneurs and structure overlap—‘provide the opportunity and means for recombination of cognitive schema and cultural models, which are then amplified by others in the sequencing of historical events’ [

22] (p. 129).

The first mechanism of change, institutional entrepreneurship, refers to individuals or organisational actors who contribute to institutional change [

23]. These actors can forge new paths in their sectors by introducing new practices [

22]. The institutional entrepreneur provides an incentive to change, since change enables innovations and modifications. However, as argued in the literature, institutional entrepreneurs should not be considered heroes [

24]; instead, they are influential agents of change. The second mechanism of change, structure overlap, refers to the modification of rules and organisational structures or a change in function according to a new logic. According to Thornton and Ocasio [

19], if structural change is based on a different logic, as in hybridism, contradictions emerge within the organisation or organisational field. Since the mechanisms interact with each other, this is an opportune moment for an institutional entrepreneur to take action. Structural change also has an effect on the organisational field, which demonstrates its contribution to the formation of IL. Such changes can be observed in deinstitutionalisation in organisational fields.

The last mechanism, event sequencing, is temporal. In this mechanism, events are analysed according to the flow of power, practices and routines in the formation of IL. Thornton and Ocasio [

19] suggest that this mechanism can be used to analyse agency capacity. It is a historical analysis of actions that have impacted the effectiveness of organisational change—the event itself and its consequences. The sequence of events leads to new events and reinforces the new logic [

22]. Such events include pressures, decisions, actions or any related element that impacts the organisation of space, the actions of an institutional entrepreneur, or changes in structure over time. According to Sewell [

25], the events worth considering are those that initiate direct action in a chain of occurrences. A simple rupture by itself rarely generates a change in structure [

25].

This approach is useful when examining institutional analysis as a process of change, which is due mainly to the cultural and historical influences on society. As an IL forms, the level of change and the result of institutional isomorphism must be considered. Even assuming a contemporary approach, the construction of the previous institutional analysis [

18] and the contribution of practices and behaviours to the institutional environment should not be neglected. Thus, practices are the basis for a better understanding of the present approach, and in the following, we describe the theoretical bridge between practices and sustainability.

4. Talking about Practices

The theoretical approach of practices includes a large, diverse set of theories taken from the social sciences. In these theories, the term practice is associated with several relatively similar terms such as

praxis, action, interaction, activity, experience and performance. These terms are linked to diverse sociological and philosophical traditions such as Marxism, action theory, structuralism, phenomenology and hermeneutics. Epistemological currents and methodological proposals under the umbrella of ‘theories of practice’ hamper the systematisation of these theories, but some effort should be made to clarify the common arguments that unite PBS and also how they differ [

4,

26,

27].

Although it is generally agreed that practices shape actors’ reality, theories of practice propose a reflection on ‘how practices constitute the system and how the system can be changed by practices’ [

26] (p. 154). A unified theory of practice should account for both questions within the same framework; however, such unification would only lead to an artificial understanding. According to Reckwitz [

27], it would be an idealistic effort. Instead, some theories focus on the context of the reproduction of practices, and others theories focus on the phenomena that imply a change in that context. According to Schatzki [

28], theorists of practice are united by a vision of society as the nexus and sense of practice. He claims that ‘practices are qualified as the basic social phenomenon, because the understanding/intelligibility articulated within (perhaps supplemented with normativity) are the basic means of ordering social life’ [

28] (p. 284).

After identifying this common ground among theories of practice, Schatzki [

28] also points out some differences in understanding the relationship between practices and actions or more precisely the way in which ‘practices and actions are intertwined’. Reckwitz [

27] also seeks to identify points of contact among different theories of practice. He describes them as ‘a family of theories that, in a certain basic way, differs from others Classic types of social theory’ [

27] (p. 244). According to him, the best way to understand theories of practice is to contrast them with other forms of cultural theory.

According to the theory of structuralism, recursiveness, meaning a cyclical pattern of actions, is what distinguishes practice [

7], although the repetition of a given action over a period of time is not enough to characterise it as a practice. Practices refer to social constructions that arise through repetition but are also maintained, renewed and combined in systems of action [

7]. They are then used to institutionalise acceptable behaviour within a group, imposing order on society. As Gherardi [

4] (p. 536) points out, ‘practices are not only recurrent patterns of action (at the level of production) but also recurrent patterns of socially sustained action (at the level of production and reproduction)’. In other words, practice refers not only to what people do on a daily basis, but to what people do daily relative to their social, historical and structural context.

The link with institutional processes becomes clear as practices evolve in structured contexts that perpetuate themselves over time [

28] and organise themselves into systems [

7]. It should be noted that practices are dynamic—they are always in motion and update through action, even though institutional processes result from recurring, stable practices. Although stable, the recursive nature of practices demands constant updating. Their institutionalisation into stable elements—which can be speeches, norms, normative objects, and personification in figures of authority, etc.—does not ensure their permanence. This understanding demands a post-structural analysis based on the assumption that when practices become institutionalised, the social knowledge they embody pours off on objective structures. Even so, a practice only exists in action, when social agents and structures collaborate to repeat and update it.

The unfolding of structuralist thinking into the post structuralist perspective leads to the understanding that structure becomes a structuring feature of practices in a recursive work. This dynamic engages the practical schemes of sense-construction arising from the incorporation of social structures that have emerged from the work of agents who preceded them in time in the action and ideas of the agents [

29]. This assumption guides the understanding of knowledge as a social construction situated in provisional practices (since practices do not exist disembodied from their practitioners), and at the same time, a stable force ‘because [practices] are always the product of specific historical conditions resulting from past practices and transformed into current practices’ [

30] (p. 215).

The theorists of practice, especially post structuralist theories [

31], acknowledge that mediation between social agents and society, or between a subject and culture, are included in the concept of a project that distinguishes the relationship between action and time. A project describes an action that finds meaning in the past and is launched into the future through the practices developed in the present. Practices can thus be defined as the modus operandi of regularities that develop progressively through incremental variations. This understanding is the key to recognising an individual agent’s active role in the reproduction of the social order. It also helps to explain how practices can be reified as entities that affect individuals’ motivations, as these motivations can never extend very far past the choices that the objective structure provides.

In the constructive relationship between practice and structure, practices emerge in Bourdieu’s [

31] reproductive circuit. This circuit describes the cyclical and reciprocal relationship in which practices create objectified social structures. An organisation emerges from the institutionalisation of practices; it comes from the recursiveness that turns actions into practices through repetition and stability. The duality of structure versus agency is reduced to the ‘incorporation of objectivity [which] is thus inseparably internalized from the collective schemes of integration into the group, since what is internalized is the product of the externalization of a subjectivity structured in a similar way’ [

31] (p. 168).

The perspective states that the system does indeed have a very powerful and even determining effect on human actions. It also adds that the actors’ interest in the action stems from the need to understand ‘where the system comes from—how it is produced and reproduced, how it may have changed in the past or how it may change in the future’ [

26] (p. 146). A perspective acknowledges the power of the system to shape human action; it also assumes that this action is not simply an execution, but rather that it is the core of the world’s meaning. In

Section 4 we defined practices; in

Section 5, we demonstrate that sustainability can be a practice.

5. Sustainability as a Practice

Sustainability is becoming more and more important in society; however, the academic study of sustainability assumes a certain ideological orientation that approaches simple common sense. This is due to the emphasis on the value of sustainability; that is, agents incorporate sustainability into their actions because it is valuable. Currently, the debates on sustainability assume an instrumental perspective that ‘gives primacy to profits over environmental and social outcomes’ [

12] (p. 17). This is an interesting point of view, but sustainability practice means more than what actions are being practiced. For Hopwood et al. [

32], sustainability is the result of a growing awareness of global environmental and socioeconomic problems. Based on these arguments, there is a useful set of theoretical constructs to help us understand and maintain sustainability.

According to Brorström [

2] (p. 26), ‘the concept of sustainability is powerful because no one opposes it’; thus, there are different lines of thinking in research on sustainability. Some studies take a broad view and examine society as a whole, whilst others take an organisational perspective in which sustainability corresponds to the triple bottom line (TBL). The TBL [

33] refers to three dimensions that define sustainability: social, economic and environmental. This approach addresses concerns with the environment and society. In the midst of diverse perspectives and interpretations, it is necessary to incorporate new ways of understanding sustainability so that individuals and organisations can institute new sustainable behaviours.

For any given perspective—environmental, political or anthropological, for example—sustainability can and should be practical because it depends on existing stakeholders to carry out the actions and meanings that make sustainability happens. Practice is a repeated action that eventually becomes rooted in one’s way of thinking or cultural values. The repetition of such an action affects agents’ actions, the objective structures produced by these actions and the way in which these actions transform the agents and the objective structures. For example, if social and environmental projects are implemented, if investments are made in sustainability and if there is a set of norms and procedures supporting sustainable actions in organisations, the social agents involved will be transformed and will conform to these organisational practices.

According to Giddens [

7], practice is the result of a structuration process; it is caused by interactions between agents and socially produced structures and from the production and reproduction of actions in daily routines. In order for an organisation to make a practice of sustainability, a set of structural definitions must be co-created by individuals with agency in that organisation; further, these sustainable actions must be repeated over time. This on-going process demonstrates how sustainability can be practiced. It is relevant to highlight that this process is never complete, as there is always fluctuation between stability and change.

Additionally, sustainability can be thought of as a practice because it must go beyond what already exists in an organisation in terms of norms and structures, taking into account what the organisation actually does and the meaning such actions generate for the public. Thus, sustainability cannot be limited to sustainability reports or certain types of communication, such as marketing campaigns. There is a direct relationship between sustainability and the structure of an organisation, which can be seen in the sharing and generation of meanings for the same logic and socially constructed results.

On the other hand, the view of practices [

29] emphasises that recurrent patterns of action develop alongside structural boundaries that also change over time. What makes sustainability particularly interesting from a practice-based approach is the fact that the agents who comprise organisations must enact it in the context of everyday relationships. Even if an organisation has the technical or functional apparatus to achieve sustainability, individuals must still put it into action.

Thus, in order to define sustainability as a practice, we must consider the significance, interpretations and real actions of organisations first at the level of what people do and second at the level of how actions become a way of thinking/understanding the meaning of organisational practices. This perspective demands an understanding that sustainability as a practice results from complex cyclical inter-relations (since it develops over time) between agents and structures as well as an understanding that it leads to a process of institutionalisation. This institutional configuration, summarised in a logic embodied by agents and incorporated in the structure, is not stable or complete; it is part of a dynamic construction and reconstruction of sustainability as a practice.

Motivation and incentives for the practice of sustainability are often limited. This is particularly true when the TBL is considered. The TBL perspective may be closer to organisational studies organisations influence it. The style of thought—in contrast to the prevalence of structuralism in the field of sustainability studies—generates its own problems. It examines the meaning, ontology and analysis of the social micro-logics of organisational practices rather than stable concepts such as ‘individuals’, ‘organisations’ and ‘society’ [

34]. Based on these micro-logics, structuralism argues that the overlapping construction of a person practicing sustainability and of the concept itself is not an organisational process that begins with the structure and becomes a practice—rather it is a social, collective process in which an organisation emerges as a result of what people do. ILS is based on these theories.

6. Institutional Logic of Sustainability

ILS is a theoretical approach to understanding how organisations perform sustainability; it incorporates the ideas of institutional logic, practices and sustainability. The ecological logic perspective [

12] dominates the literature, but in this paper, all of the dimensions of sustainability receive the same level of analysis so that we may better understand sustainability as a practice. Friedland and Alford [

20] claim that ILs (family, religion, capitalism, etc.) are symbolically founded, organisationally structured, politically defended and technically and materially restricted; therefore, they have specific historical limits. Accordingly, since society consists of a group of different institutions, various ILs are performed simultaneously in society. Therefore, as a result of socially constructed standards, ILs can assume different classifications and perspectives, depending on the interactions among individuals, organisations and society.

ILs can be seen as a dominant logic covering companies’, individuals’ or groups’ mind-sets; IL can also be seen as competing logics, in which it is possible to assume different logics according to the characteristics of the organisational field. Related to sustainability, both are possible; however, sustainability as a practice facilitates the emergence of a new dominant logic. It is therefore possible to analyse how sustainability arises as a practice when actions related to sustainability are performed through structures that have been created with the goal of increasing sustainability in an organisation. When actions and structures converge, perpetuating one another, an IL of sustainability may emerge. Thus, we define ILS as follows:

The outcome of actions—developed and institutionalised by organisations—that improve the sustainability of a given organisational field. The practice of sustainability emerges in the context of actions within institutional structures that were created to improve sustainability. The ILS emerges as both the cause and consequence of the practice of sustainability; it enables new agent practices, new structures or structural changes and new organisational actions that further support it.

When sustainability is considered as a social value, it can be removed from its material and symbolic perspective, clarifying it can be shared between organisations and individuals. Sustainability as a practice occurs with the technical/functional support of the organisation manifests as a continuous repetition that moves toward change. Therefore, the practice of sustainability is both stable and unstable—which is difficult to understand when practices are analysed as discrete objects and not on a time continuum. Although the structuralism theory of practice as routine accounts for a path, it is limited to the customary movement of agents moving in ‘cycles of action’ [

35]. However, ‘cycles of action’, as expected in the theory of practice as routine, are very different from the ‘circuits of reproduction’ [

31] that underlie the cyclical, reciprocal relationship through which a practice creates and recreates the structures and conditions that perpetuate it.

From a perspective, practices retain the inherent temporal quality of a cycle, but they also acquire the transcendent temporal quality of constant progression. They can repeat continuously, but each repetition is modified. The formation of a new institutional logic is supported by the three mechanisms of change described previously. Therefore, this section analyses the institutional entrepreneurship, structure overlap and event sequencing of the ILS to support its promotion. However, the idea of sustainability as a practice must be added to this analysis, along with a focus on the meanings, interpretations and real actions of organisations. These four dimensions outline the necessary requirements for the formation of an ILS (see

Figure 1).

Figure 1 can also be explained through a parallel with geometry. ILS creates a spiral that develops as one point (the practice itself), moves in a circular direction (the repetition) and experiences linear force (the passage of time). Practices that follow each other chronologically are like turns in the spiral—they develop in continuity, they are similar to one another and they are transformed according to a constant ratio. ILS is then an analytical lens to understand change for the sake of sustainability.

Furthermore, each of the mechanisms of change can be used to support the formation of an ILS. The sequence of events is a temporal and spatial support mechanism that leads to a broader understanding of events. As the initial structure changes into one that is embedded with the ILS, it is necessary to recognise such events, mainly because this enables an organisation to recognise the pressures and motivations for change and support new changes. Thus, if the person responsible for projects or programmes of change is absent, other agents who understand the whole process can continue developing the same line of work.

Institutional entrepreneurship affects the development of ILS. As Peters et al. [

36] point out, the institutional actor acts positively when searching for sustainability in organisations. They also suggest that focusing on the institutional entrepreneur makes it possible to identify how an organisation implements sustainability strategies. This view presents some problems for the discussion in this paper, but it may also support the arguments made here through observation. Institutional entrepreneurship also affects structure: ‘the only moving object in human social relations are individual agents, who employ resources for things to happen, intentionally or unintentionally’ [

7] (p. 213).

Finally, a change in structure directly on the agency of the institutional entrepreneur and on the events that have occurred. According to Giddens [

7] (p. 218), ‘understood as rules and resources, structure is repeatedly implied in the reproduction of social systems’. The flow of practice is inherent to sustainability because it affects agents’ actions in a given space and time; thus, it is possible to elaborate the abstraction of a structure that is produced or reproduced in the social system. The intersection of these four dimensions is the basis for the formation of the ILS.

7. Discussion

Applying PBS to IL allows us to comprehend sustainability as a practice. Hence, by using a new theoretical approach, we contribute to the sustainability literature which is still fragile related to organisational studies. The social sciences make valuable contributions to our understanding of sustainability, and an open dialog with the field of organisation studies could facilitate greater understanding of the theme. The purpose of this conceptual paper is to examine the potential of the interaction among sustainability, institutional logic and theories of practice. We also question the functionalist perspective (i.e., instrumental) that guides the status quo of discussions about sustainability. The concept of practices is especially interesting in light of the way sustainability is often seen as stable and ready-to-use but has to be continuously reinforced in order to exist. Sustainability as a practice combines these peculiarities: continuous repetition that constantly moves toward change.

Institutional analysis supports sustainability as a practice by describing how constantly repeated actions become practices, which in turn influences the formation of an organisation and its stability and changes. Therefore, when developing a theory around the logic of sustainability, it must be understood that an organisation grows out of the process of institutionalising practices. In fact, practices can be described as ‘a socially recognized and relatively stable way of ordering heterogeneous items into a coherent set’ [

37] (p. 34). Thus, the practice-based theory can contribute to the understanding of the logic of sustainability. This aligns with several studies that divide sustainability into different organisational areas such as: strategy [

2,

38], supply chain management [

39], and organisational learning [

9].

The most important contribution of PBS to the field of organisational studies is the understanding that practices are a system of activities in which knowing cannot be separated from doing [

30,

40,

41,

42]. The studies that support this view also acknowledge that knowledge does not reside in individuals’ minds it is not an individual cognitive resource but something that people do together. After all, the process of knowing something and transmitting knowledge is a social practice. These studies tend to seek explanations for why particular practices have emerged, how they have been institutionalised and how they change over time. Similar studies could be done in the field of sustainability. It could be examined as a practice built of agents’ daily actions in the course of historical processes and as a cause and a consequence of cultural changes in a given context. For instance, Liedtke et al. [

3] claim that in the transition to sustainability, changes in practices are possible through a sustainable product-service-design. To explain this the authors cite bathing and nutrition practices that have caused massive changes regarding skills and habits in society.

A common research focus for PBS in organisational studies is established practices such as high French cuisine [

43], security on construction sites [

44], making an instrument, like a flute [

45] and building a roof [

46]. Even assuming stability as a starting point, studies like these assume that practices, in their intended prescriptions of action and goals, can have stable features at certain moments, even though their practitioners and the environment in which they are practiced change over time. Other studies analyse the process of the constitution and the continuous reconstitution of practices [

47,

48,

49]. These studies are particularly interested in the formation of practices [

50]. Related to sustainability some studies seek to reduce the sustainability gap by analysing sustainable strategy formation [

38], yet other study citizen-consumers as agents of changes [

51].

Another unexplored area of research is the nature of sustainability. Studies could be done to determine a set of actions that define sustainability. Such studies would help to explain how actions become incorporated into the culture of agents and organisational structures. It is also necessary to unravel the dynamic character of the practice of sustainability in order to describe how sustainability is created in the process of doing it. Thus, when the concept of sustainability is put into action, it ultimately changes the practice of sustainability to conform to the idea of sustainability as a practice. The concept of sustainability is a verb rather than a noun; it incorporates dynamic action. As an organisation transitions to organising [

52] and a strategy transitions to strategising [

5], studies of sustainability practices emphasise the object, limiting sustainability to a stable, narrow noun; since its meaning is self contained, it does not act on other objects.

Regarding IL studies, several researchers have attempted to increase the consistency in this theoretical approach. Their studies are related to organisational ecology [

11], innovation [

53], supply chain management [

12,

54], and social entrepreneurship [

9]. Several PBS have been done on sustainability, especially on the transition to sustainability, which is an emerging area of research [

3,

55,

56]; there are also those that examine sustainability within the field of strategy studies [

2,

38]. However, these studies are limited. Sustainability research needs to focus more on theory and seek to understand sustainability as a practice rather than something that organisations have. Our proposal of an ILS is relevant to this problem. We must stress, however, that the four aspects of IL (institutional entrepreneurship, event sequencing, structure overlap and practice of sustainability) are adaptable and can be analysed from different perspectives; further they can be used to support different epistemological lenses, opening the possibility of new theoretical debates on the topic.

This discussion should be extended to consider additional characteristics of sustainability. This occurs, for example, when the element of time is considered in an analysis of sustainability. How does time influence event sequencing? Is it directly related to the performance of the person who developed a particular activity (institutional entrepreneur)? How does it affect changes in structure? How does sustainability occur over time (sustainability as a practice)? Certainly, the past is important, but the time frame for practices is neither linear nor cyclical, leading to another image of permanence and another relationship to change. Therefore, in observing what an organisation has practiced in the past, it is important to recognise the possibility of the emergence of a shared, socially constructed identity—an ILS.

8. Conclusions

In this conceptual paper, we examine the debates over different theoretical perspectives on the practice of sustainability. First, it must be understood that sustainability is something that has to be put into practice by agents, actions and structures, and it must be done over time. Another possible approach to this work is to view sustainability as a practice that can be studied from different theoretical perspectives under the umbrella of ‘theories of practice’. Thus, sustainability as a practice plays an important role in sustainability studies. The theoretical argument that we develop here is situated on the continuum between structuralism and post-structuralism. Given the rarity of in-depth discussions on practices in sustainability studies based on the theory of PBS, this paper represents a first step towards a more open, in-depth dialogue between the fields of practice and sustainability. However, the general discussion on practices is much broader than the one introduced here, and other aspects of theories of practice that are not mentioned in this paper may also be relevant to a discussion of sustainability.

One limitation of this paper is the difficulty in providing examples, as more theoretical and empirical research is needed to understand sustainability as a practice. Thus, since ILS is a drive to understand sustainability in the real world, some possible topics in further research could include: the organisational practices that emerge from the practice of sustainability; the fact that sustainability only exists in relation to organisational structures but does not have to be practiced, especially in a field that focuses on results and that ignores the fact that sustainability needs to be continually updated and cannot be sustained by structures alone (i.e., the possibility of not practicing sustainability); and the breakdown of the structures (that has guided structuralism-based debates about sustainability) to understand sustainability in terms of what agents do in time and space. These studies could have practical implications for different organisational areas such as: strategic management, operations management and human resources management. Further, these studies could help to create a stronger theoretical field that would contribute to the development of sustainability as both a research field and as an essential social practice.