Employees’ Participation in Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Person–CSR Fit

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. The Importance of the Employee to an Organization

2.2. CSR and the Employee

2.3. Person–CSR Fit

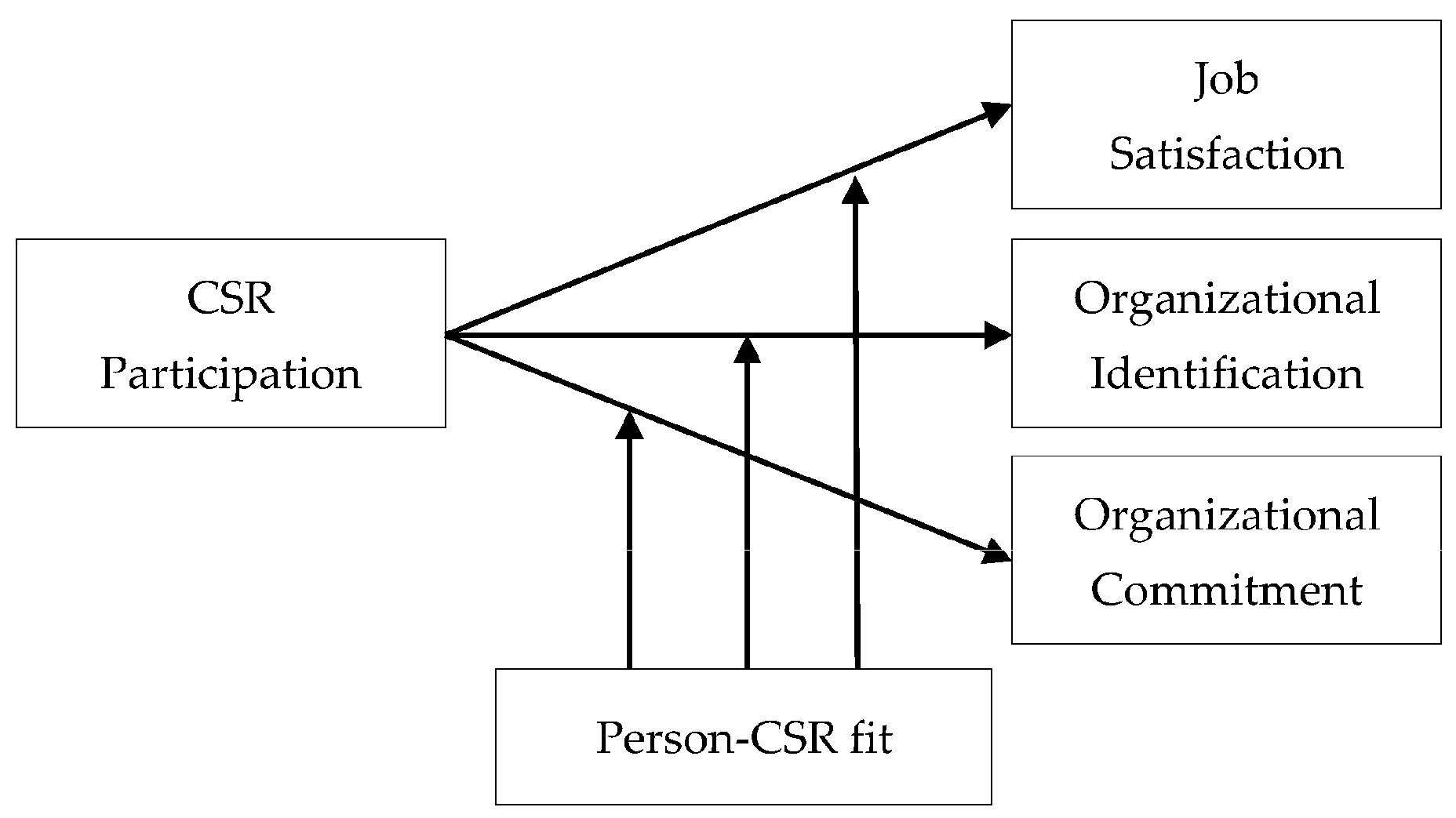

2.4. Moderating Role of Person–CSR Fit

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurement

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Test

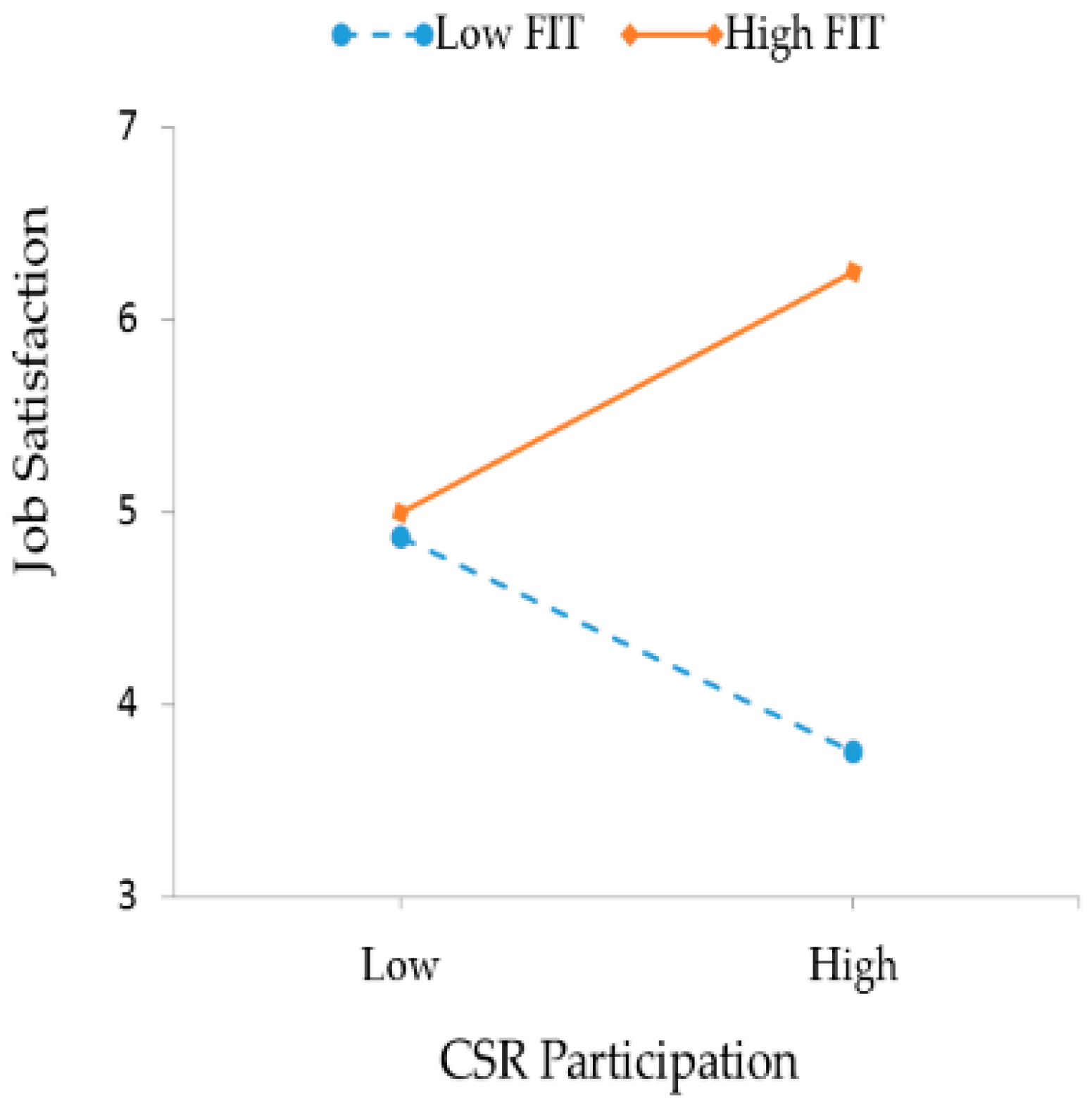

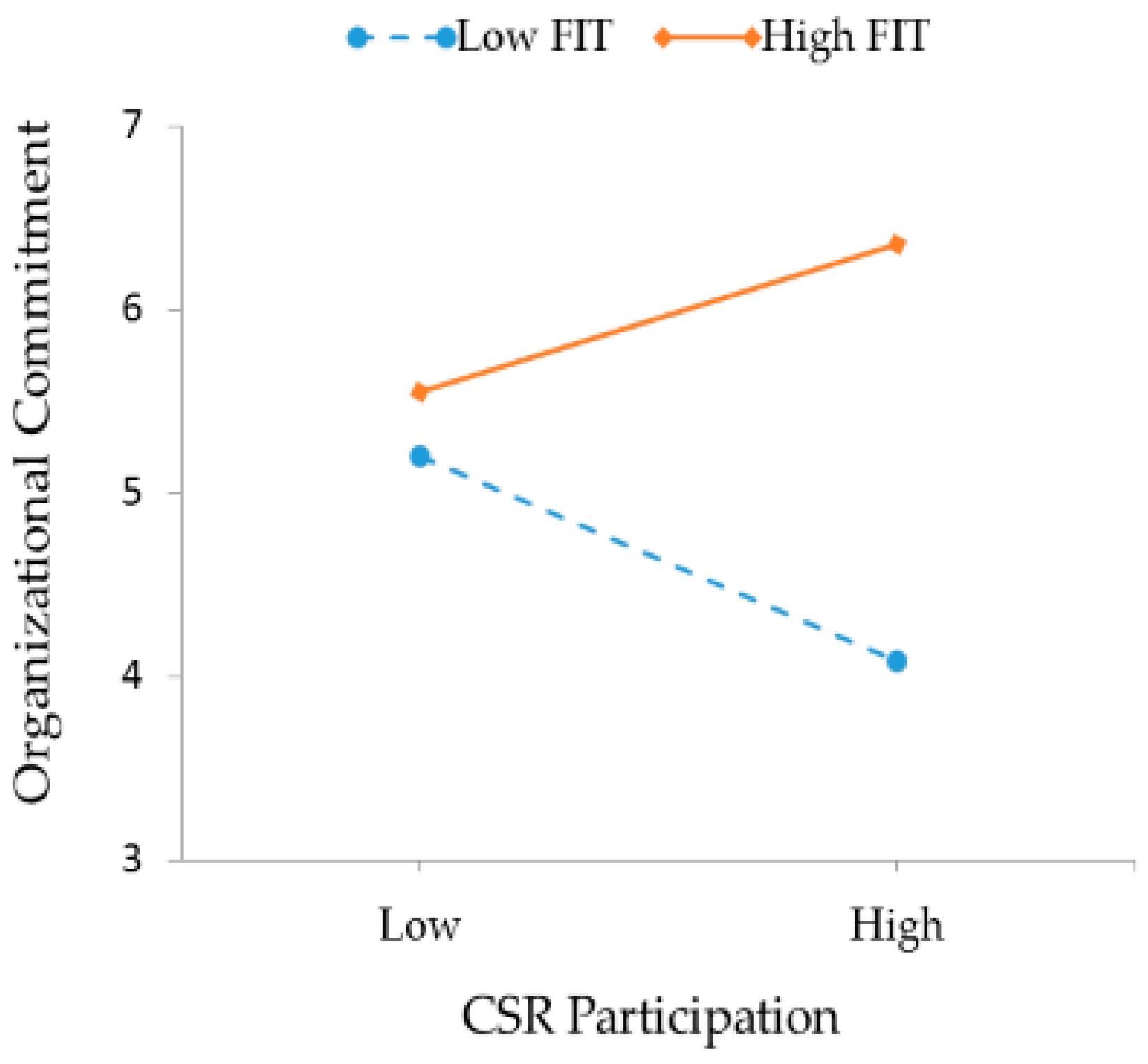

4.2. Hypotheses Test

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Measurement Items |

|---|---|

| CSR participation | I work as a team on CSR activities. I have ample opportunity to suggest CSR activities. |

| Person–CRS fit | My organization’s CSR activities are relevant with my values. My organization’s CSR activities reflect my own values and personality. My organization’s CSR activities are congruent with my interests. |

| Job satisfaction | My job is very worthwhile. My job is very pleasant.I am very content with my job. |

| Organizational identification | I feel strong ties with my company. I experience a strong sense of belongingness to my company. I am part of my company. |

| Organizational commitment | I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization. I enjoy discussing my organization with people outside the organization. I do not feel emotionally attached to this organization (R). |

References

- Chen, Y.R.; Hung-Baesecke, C.F. Examining the internal aspect of corporate social responsibility (CSR): Leader behavior and employee CSR participation. Commun. Res. Rep. 2014, 31, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, G.; van Riel, C.B.M.; van Bruggen, G.H. Corporate associations and consumer product responses: The moderating role of corporate brand dominance. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, T.; Colwell, A.; Cunningham, P.H. The emergence of corporate social responsibility in Chile: The importance of authenticity and social networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, R.; Yang, W. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Lin, H. The correlation of CSR and consumer behavior: A study of convenience store. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.; Yeo, J. Corporate brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between consumer perception of CSR, corporate hypocrisy, and corporate reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, D.R.; Drumwright, M.E.; Braig, B.M. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer donations to corporate-supported non-profits. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Preston, L.E.; Sachs, S. Managing the extended enterprise: The new stakeholder view. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2002, 45, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaler, J. An optimally viable version of stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 86, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, M.T. Corporate social responsibility and employee behavior: Mediating role of organizational commitment. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2016, 18, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korschun, D.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Swain, S.D. Corporate social responsibility, customer orientation, and the job performance of frontline employees. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yin, H.; Liu, J.; Lai, K. How is employee perception of organizational efforts in corporate social responsibility related to their satisfaction and loyalty towards developing harmonious society in Chinese enterprises? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 21, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.D.; Dunford, B.B.; Boss, A.D.; Boss, R.W.; Angermeier, I. Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.; Lee, H. Employee perception of CSR activities: Its antecedents and consequences. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A. Feeling good by doing good: Employee CSR-Induced attributions, job satisfaction, and the role of charismatic employee perception of CSR activities, job attachment and organizational commitment. J. Bus Ethics 2013, 118, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Y.S.; Han, J.K.; Lee, S. Communication strategies for enhancing perceived fit in the CSR sponsorship context. Int. J. Adv. 2012, 31, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattachary, C.B.; Korschun, D.; Sen, S. Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. J Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pittman-Ballinger: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Roeck, R.D.; Delobbe, N. Do environmental CSR initiatives serve organizations’ legitimacy in the oil industry? Exploring employees’ reactions through organizational identification theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 110, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.; Kim, N. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, T.; Hur, W.; Ko, S.; Kim, J.; Yoon, S. Bridging corporate social responsibility and compassion at work. Career Dev. Int. 2014, 19, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.S.; Shin, Y.; Choi, J.N.; Kim, M.S. How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. J. Manag. 2011, 39, 853–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supnati, D.; Butehr, K.; Fredline, L. Enhancing the employer-employee relationship through corporate social responsibility (CSR) engagement. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1479–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; He, H.; Mellahi, K. Corporate social responsibility, employee organizational identification, and creative effort: The moderating impact of corporate ability. Group Organ. Manag. 2015, 40, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.W.; Turban, D.T. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Whitener, E.M.; Brodt, S.E.; Korsgaard, M.A.; Werner, J.M. Managers as initiators of trust: An exchange relationship framework for understanding managerial trustworthy behavior. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 513–530. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 25, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, L.; Cunningham, P. To thine own self be true? Employees’ judgments of the authenticity of their organization’s corporate social responsibility program. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, D.; Tushman, M. A model for diagnosing organizational behavior: Applying a congruence perspective. Organ. Dyn. 1980, 9, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.W. The role of person-organization fit and perceived organizational support in the relationship between workplace ostracism and behavioral outcomes. Aust. J. Manag. in press.

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, A.R.; Gallagher, V.C.; Brouer, R.L.; Sablynski, C.J. When person-organization (mis)fit and (dis)satisfaction lead to turnover: The moderating role of perceived job mobility. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Ferris, G.R. The elusive criterion of fit in human resource staffing decisions. Hum. Resour. Plan. 1992, 15, 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kristoff, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of item conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozes, M.; Josman, Z.; Yaniv, E. Corporate social responsibility organizational identification and motivation. Soc. Responsib. J. 2011, 7, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilies, R.; Scott, B.R.; Judge, T.A. The interactive effects of personal traits and experienced states on intra-individual patterns of citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roecka, K.D.; Marique, G.; Stinglhamberb, F.; Swaena, V. Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organisational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.C.; Boo, E.H.Y. The link between organizational ethics and job satisfaction: A study of managers in Singapore. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Corporate social responsibility, multi-faceted job-products, and employee outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posnver, B.Z. Another look at the impact of personal and organizational values congruency. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. Embedded versus peripheral corporate social responsibility: Psychological Foundations. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2013, 6, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhapakdi, A.; Lee, D.; Sirgy, M.J.; Senasu, K. The impact of incongruity between an organization’s CSR orientation and its employees’ CSR orientation on employees’ quality of work life. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vianen, A.E.M.; Nijstad, B.A.; Voskuijl, O.F. A person-environment fit approach to volunteerism: Volunteer personality fit and culture fit as predictors of affective outcomes. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 30, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks-Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.G. To be or not to be: Central questions in organizational identification. In Identity in Organizations: Building Theory through Conversations; Whetten, D.A., Godfrey, P.C., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 171–207. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J.; Oakes, P. The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 25, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callero, P.L. Role-identity salience. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1985, 48, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.B.; German, S.D.; Hunt, S.D. The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A. Corporations, culture, and commitment: Motivation and social control in organizations. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1989, 58, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Testing the ‘side bet theory’ of organizational commitment: Some methodological considerations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1984, 69, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Shao, R.; Thornton, M.A.; Skarlicki, D.P. Applicants and employees reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 895–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, N.G.; Rapp, A.A.; Vlachos, P.A. I think they think we are good citizens: Meta-perceptions as antecedents of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2781–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretz, R.D., Jr.; Judge, T.A. Person–organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 44, 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.N.; Rutherford, B.N.; Park, J. Emotional labor’s impact in a retail environment. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2238–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; SAGE: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rodell, J.B.; Breitsohl, H.; Schroder, M. Employee Volunteering: A review and framework for future research. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Morris, S.C.R. Exploring employee engagement with (corporate) social responsibility: A social exchange perspective on organisational participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| M | SD | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CSR participation | 5.70 | 1.00 | ||||

| 2. Person–CSR fit | 5.59 | 0.96 | 0.52 ** | |||

| 3. Job satisfaction | 5.42 | 1.11 | 0.28 ** | 0.37 ** | ||

| 4. Organizational identification | 5.73 | 1.00 | 0.30 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.64 ** | |

| 5. Organizational commitment | 5.66 | 1.05 | 0.26 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.84 ** |

| Standardized Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR participation 1 | 0.97 *** | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.93 |

| CSR participation 2 | 0.95 *** | |||

| Person–CRS fit 1 | 0.79 *** | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.70 |

| Person–CRS fit 2 | 0.86 *** | |||

| Person–CRS fit 3 | 0.86 *** | |||

| Job satisfaction 1 | 0.94 *** | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.84 |

| Job satisfaction 2 | 0.95 *** | |||

| Job satisfaction 3 | 0.87 *** | |||

| Organizational identification 1 | 0.81 *** | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.77 |

| Organizational identification 2 | 0.92 *** | |||

| Organizational identification 3 | 0.91 *** | |||

| Organizational commitment 1 | 0.92 *** | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.81 |

| Organizational commitment 2 | 0.90 *** | |||

| Organizational commitment 3 | 0.88 *** |

| Job Satisfaction | Organizational Identification | Organizational Commitment | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Step1 | Step2 | Step3 | Step1 | Stpe2 | Step3 | Step1 | Step2 | Step3 | ||

| Control variables | |||||||||||

| Gender | 0.44 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.32 * | 0.33 ** | 0.30 * | 0.24 * | 0.41 * | 0.37 * | 0.31 * | ||

| Education | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.12 | ||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| Tenure | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | ||

| Independent Variables | |||||||||||

| CSR participation | 0.31 *** | 0.20 ** | 0.30 *** | 0.21 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.17 ** | |||||

| Moderator | |||||||||||

| Person–CSR fit | 0.33 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.31 *** | ||||||||

| Interaction | |||||||||||

| CSR participation Person–CSR fit | 0.19 *** | 0.11 * | 0.16 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.25 | ||

| ΔR2 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.09 | ||

| F | 6.24 *** | 11.67 *** | 15.84 *** | 6.84 *** | 12.99 *** | 13.07 *** | 9.37 *** | 13.58 *** | 16.37 *** | ||

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Im, S.; Chung, Y.W.; Yang, J.Y. Employees’ Participation in Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Person–CSR Fit. Sustainability 2017, 9, 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010028

Im S, Chung YW, Yang JY. Employees’ Participation in Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Person–CSR Fit. Sustainability. 2017; 9(1):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010028

Chicago/Turabian StyleIm, Seunghee, Yang Woon Chung, and Ji Yeon Yang. 2017. "Employees’ Participation in Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Outcomes: The Moderating Role of Person–CSR Fit" Sustainability 9, no. 1: 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9010028