Sustainability Management with the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard in SMEs: Findings from an Austrian Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

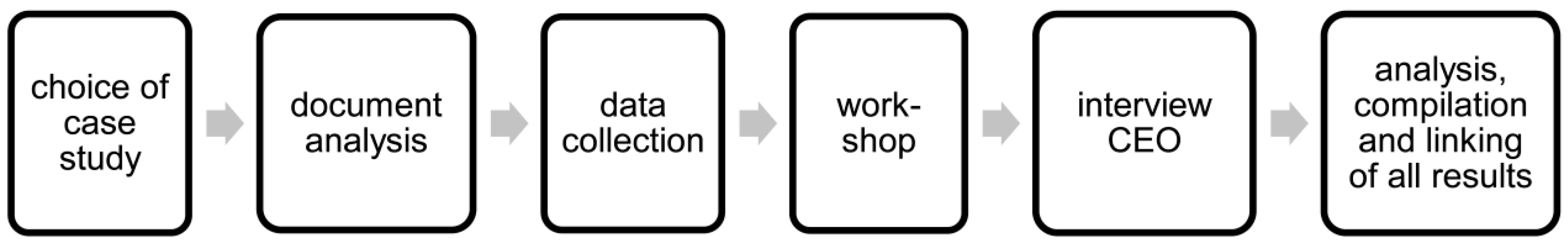

- -

- Based on an analysis of a single-case study, how does the development process of an SBSC in an SME look like?

- -

- What factors support or challenge the development of an SBSC in an SME?

2. The Development of the SBSC Framework in SMEs

2.1. The SBSC in General

2.2. The SME Context

2.3. The SBSC Development Process in SMEs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Selection of Case

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

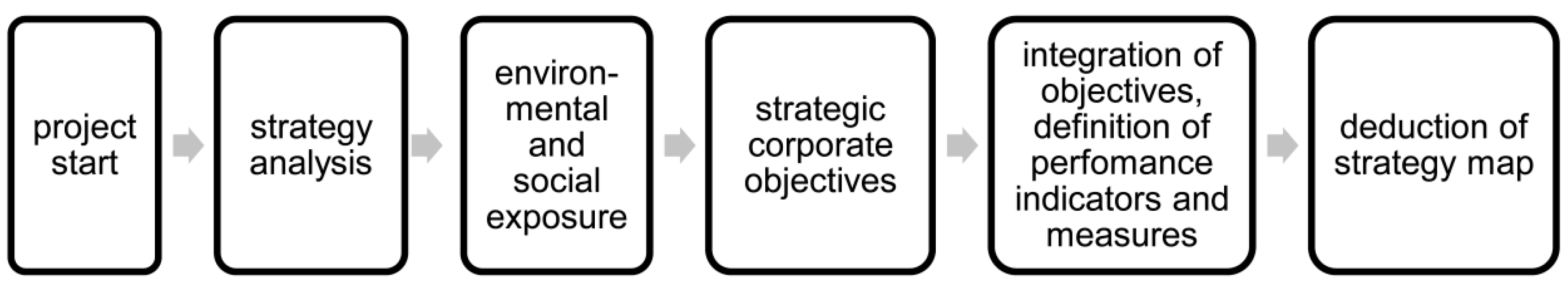

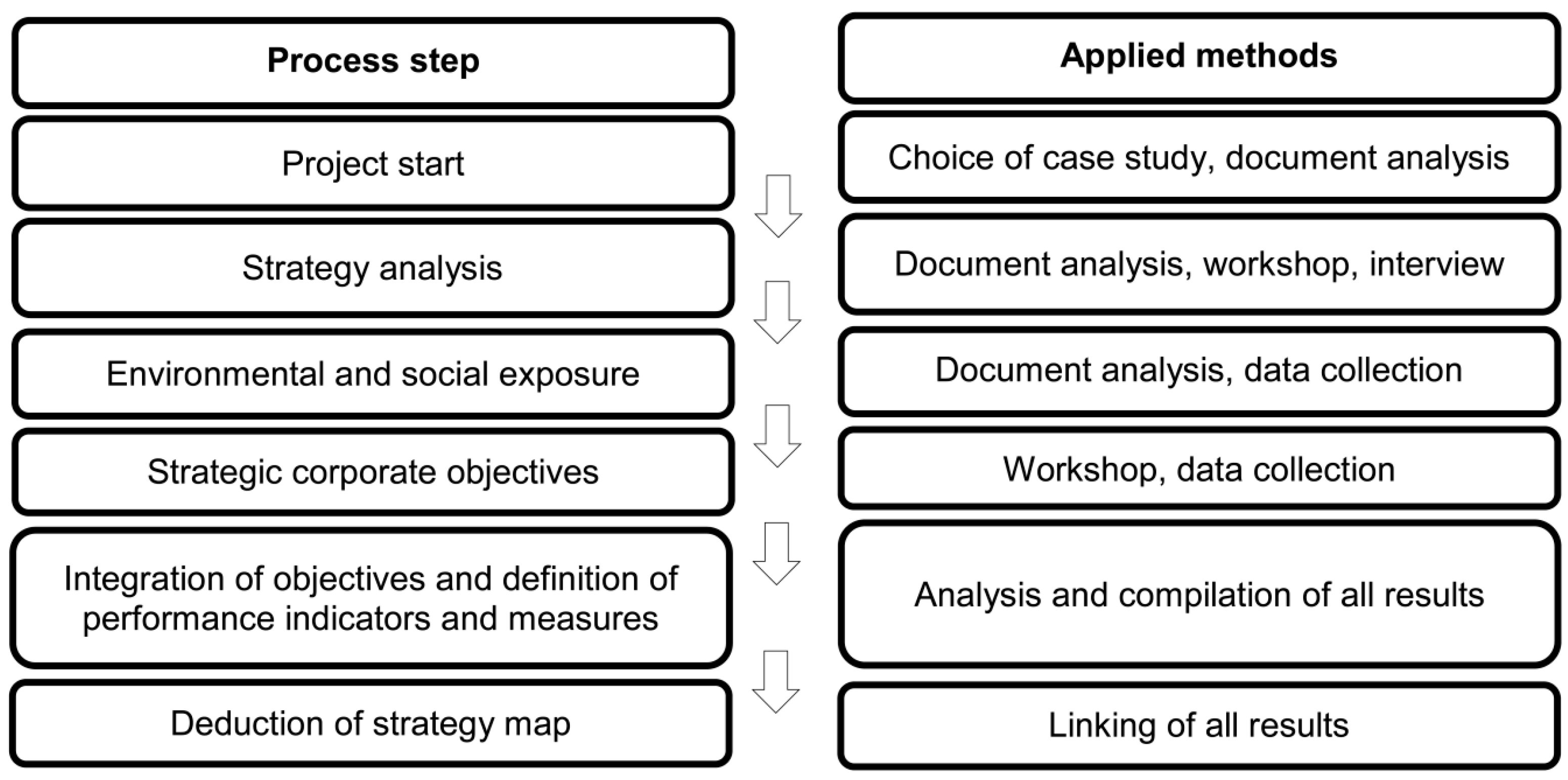

4. Case Study: Project Phases and Results Gained from the Different Development Phases

4.1. Project Start

4.2. Strategy Analysis

4.3. Environmental and Social Exposure

4.4. Strategic Corporate Objectives

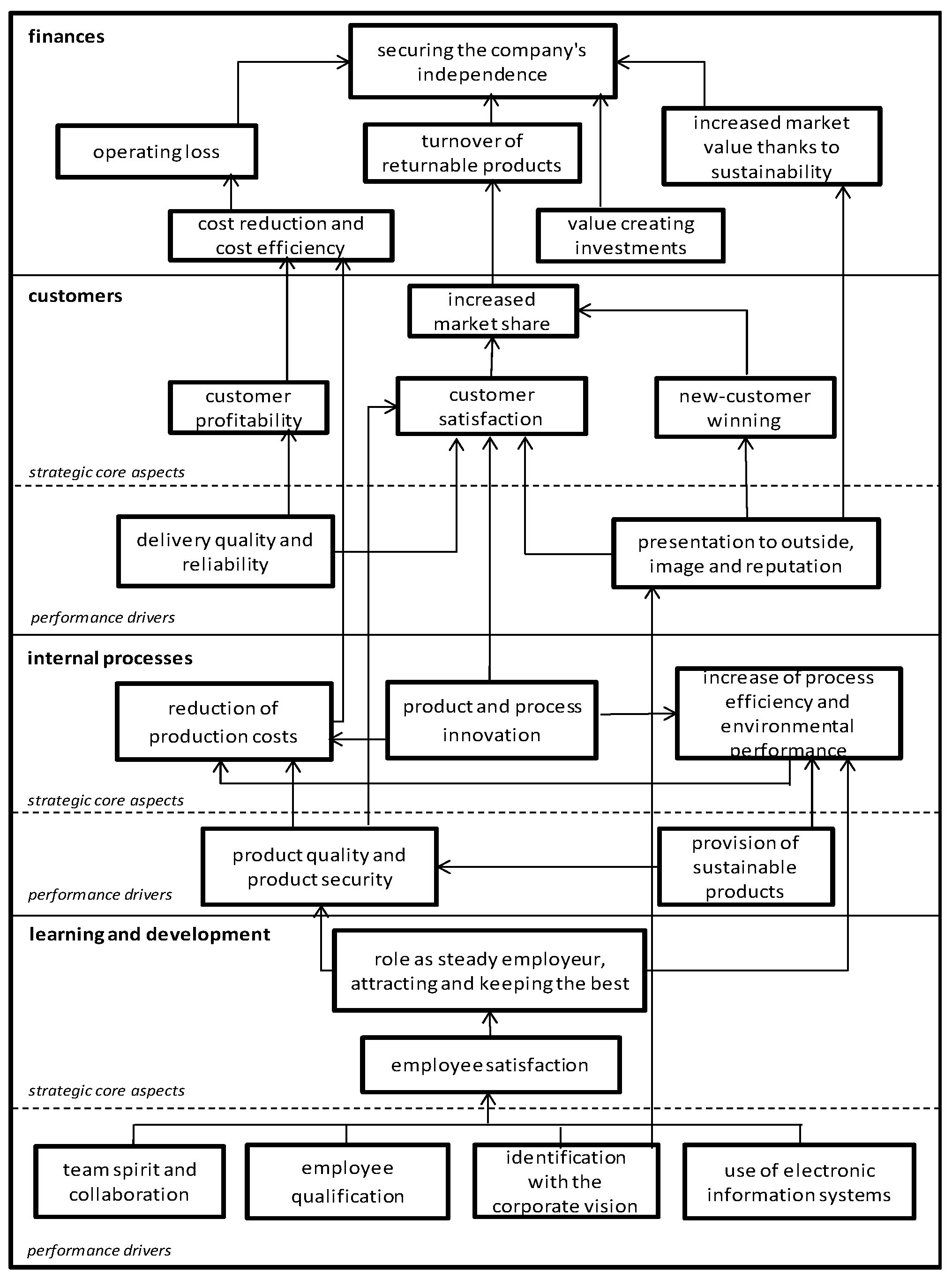

4.5. Integration of Objectives and Definition of Performance Indicators and Measures

4.6. Deduction of Strategy Map

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SBSC | Sustainability Balanced Scorecard |

| SME | small and medium sized enterprise |

References

- Bos-Brouwers, H.J.E. Corporate sustainability and innovation in SMEs: Evidence of themes and activities in practice. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard—Linking Sustainability Management to Business Strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD); Deloitte & Touche; World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). Business Strategy for the 90s; IISD: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Von Bugoslawski, A.; Payer, T. Nachhaltigkeit im Unternehmen verankern—Die Sustainable Balanced Scorecard. In Proceedings of the Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement-Praxisorientierte Ansätze und Instrumente für Eine Nachhaltige Unternehmensausrichtung, Ulm, Germany, 27 January 2005; pp. 19–24.

- Grothe, A.; Marke, N. Nachhaltiges Wirtschaften—Eine besondere Herausforderung für KMU. In Nachhaltiges Wirtschaften für KMU. Ansätze zur Implementierung von Nachhaltigkeitsaspekten; Grothe, A., Ed.; Oekom: München, Germany, 2012; pp. 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. Two Decades of Sustainability Management Tools for SMEs: How Far Have We Come? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 481–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, K.J.; Raja, V.; Whalley, A. Lessons from implementing the balanced scorecard in a small and medium size manufacturing organization. Technovation 2006, 26, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbmann, U.; Baumgartner, R.J. Strategische Implementierung von CSR in KMU. In Corporate Social Responsibility: Verantwortungsvolle Unternehmensführung in Theorie und Praxis; Schneider, A., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Partial and Fragile Recovery. Annual Report on European SMEs 2013/2014; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C.M.; Redmond, J.; Simpson, M. A review of interventions to encourage SMEs to make environmental improvements. Environ. Plan. C 2009, 27, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Redmond, J.; Sheridan, L.; Wang, C.; Goeft, U. Small and Medium Enterprises and the Environment: Barriers, Drivers, Innovation and Best Practice: A Review of the Literature; Small & Medium Enterprise Research Centre, Edith Cowan University: Joondalup, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Aykol, B.; Leonidou, L.C. Researching the green practices of smaller service firms: A theoretical, methodological, and empirical assessment. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2014, 53, 1264–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.R.E.; Collins, E.; Pavlovich, K.; Arunachalam, M. Sustainability Practices in SMEs: The case of New Zealand. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T.A.; Nikolaou, I.E.; Grigoroudis, E.; Tsagarakis, K.P. A framework development to evaluate the needs of SMEs in order to adopt a sustainability-balanced scorecard. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2013, 10, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagada, G. Using Balanced Scorecard to Drive Performance in Small and Medium Enterprises. Ekon. Manag. 2012, 1, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, H.; Cobbold, I.; Lawrie, G. Balanced Scorecard Implementation in SMEs: Reflection in literature and practice. In Proceedings of SMESME Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 14–16 May 2001.

- Suprapto, B.; Wahabm, H.A.; Wibowo, A.J. The Implementation of Balance Score Card for Performance Measurement in Small and Medium Enterprises: Evidence from Malaysian Health Care Services. Asian J. Technol. Manag. 2009, 2, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Bieder, T.; Friese, A.; Hahn, T. Axel Springer Verlag: Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement am Druckstandort. In Nachhaltig Managen mit der Balanced Scorecard. Konzept und Fallstudien; Schaltegger, S., Dyllick, T., Eds.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; pp. 167–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bieker, T.; Herbst, S.; Minte, H. Nachhaltigkeitskonzept für die Konzernforschung der Volkswagen AG. In Nachhaltig Managen mit der Balanced Scorecard. Konzept und Fallstudien; Schaltegger, S., Dyllick, T., Eds.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar]

- Botschen, S.; Hahn, T.; Wagner, M. OBI: Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement mit dem FOX. In Nachhaltig Managen mit der Balanced Scorecard. Konzept und Fallstudien; Schaltegger, S., Dyllick, T., Eds.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Papalexandris, A.; Ioannou, G.; Prastacos, G. Implementing the Balanced Scorecard in Greece: A Software Firm’s Experience. Long Range Plan. 2004, 37, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. Concept and the Case of Hamburg Airport; Leuphana Universität Lüneburg: Lüneburg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, W.; Freimann, J.; Kurz, R. Grundlagen und Bausteine einer Sustainable Balanced Scorecard (SBS). Überlegungen zur Entwicklung einer SBS für mittelständische Unternehmen. In Werkstattreihe Betriebliche Umweltpolitik; Freimann, J., Ed.; Universität Kassel: Kassel, Germany, 2001; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Fresner, J.; Engelhardt, G.; Wolf, P.; Nussbaumer, R.; Grabher, A.; Kumpf, A. Sustainability Balanced Scorecard im Nachhaltigkeitsbereich (ÖKOPROFIT). In Berichte aus Energie- und Umweltforschung; Bundesministerium für Verkehr, Innovation und Technologie: Wien, Austria, 2006; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Searcy, C. Corporate sustainability performance measurement systems: A review and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verband der Brauereien Österreichs. Statistische Daten über die Österreichische Brauwirtschaft; Verband der Brauereien Österreichs: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rompho, N. Why the Balanced Scorecard Fails in SMEs: A Case Study. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D. Balanced Scorecard: Strategien Erfolgreich Umsetzen; Schäffer-Poeschel: Stuttgart, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa Marques, M.d.C. Strategic Management and Balanced Scorecard: The Particular Case of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Portugal. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, L.T. Balanced Scorecard Implementation at Rang Dong Plastic Joint-Stock Company (RDP). Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 5, 126–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.G.; Schaltegger, S. The Sustainability Balanced Scorecard: A Systematic Review of Architectures. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T.; Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. Wertorientiertes Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement mit der Balanced Scorecard; Leuphana Universität Lüneburg: Lüneburg, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gminder, C.U.; Bieker, T. Managing Corporate Social Responsibility by using the “Sustainability-Balanced Scorecard”. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference of the Greening of Industry Network, Göteborg, Sweden, 23–26 June 2002.

- Hahn, T.; Wagner, M.; Figge, F.; Schaltegger, S. Wertorientiertes Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement mit einer Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. In Nachhaltig Managen mit der Balanced Scorecard. Konzept und Fallstudien; Schaltegger, S., Dyllick, T., Eds.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; pp. 43–94. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Hoejmose, S.; Marchant, K. Environmental management in SMEs in the UK: Practices, pressures and perceived benefits. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2012, 21, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, K.; Klingenberg, B.; Rider, C. Towards Sustainability: Examining the Drivers and Change Process within SMEs. J. Manag. Sustain. 2013, 3, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, C.; Hermann, S. Nachhaltige Strategieumsetzung in KMU mit der Sustainable Balanced Scorecard. An Unternehmenswerten und politischem Rahmen ansetzen. Ökol. Wirtsch. 2003, 2, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bieker, T.; Dyllick, T.; Gminder, C.U. Nachhaltig managen mit der BSC: Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. Manag. Qual. 2003, 1–2, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, I.E.; Tsalis, T.A. Development of a Sustainable Balanced Scorecard Framework. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 34, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gminder, C.U.; Bergner, M. Die Weiterentwicklung der BSC bei den Berliner Wasserwerken. In Nachhaltig Managen mit der Balanced Scorecard. Konzept und Fallstudien; Schaltegger, S., Dyllick, T., Eds.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2002; pp. 199–228. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwat, R.; Sharma, M.K. Performance measurement of supply chain management: A balanced scorecard approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2007, 53, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research. Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McNiff, J. Action Research: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brüsemeister, T. Qualitative Forschung; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, C.; Gummession, E. Action research in marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, R.; Vieira, R. Insights from action research: Implementing the balanced scorecard at a wind-farm company. Int. J. Prod. Perf. Manag. 2010, 59, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H.N. Towards rigour in action research: A case study in marketing planning. Eur. J. Mark. 2004, 38, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, U. Triangulation: Eine Einführung; Springer: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Funkl, E.; Tschandl, M.; Heinrich, J.W. Die Balanced Scorecard als Instrument im Umweltcontrolling. In Integriertes Umweltcontrolling: Von der Stoffstromanalyse zum Bewertungs- und Informationssystem, 2nd ed.; Tschandl, P., Posch, A., Eds.; Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 179–201. [Google Scholar]

- Papalexandris, A.; Ioannou, G.; Prastacos, G.; Soderquist, K.E. An Integrated Methodology for Putting the Balanced Scorecard into Action. Eur. Manag. J. 2005, 23, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanagha, S.; Volberda, H.; Oshri, I. Business model renewal and ambidexterity: Structural alteration and strategy formation process during transition to a Cloud business model. R&D Manag. 2014, 44, 322–340. [Google Scholar]

- Ioppolo, G.; Saija, G.; Salomone, R. Developing a Territory Balanced Scorecard approach to manage projects for local development: Two case studies. Land Use Pol. 2012, 29, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Environmental Aspect | Status Quo | Target State | Measures | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emissions |  | Substitution of heating oil with district heating from biomass | ||

| 2 | 1 | ||

| 2 | 1 | Consideration of emission categories at truck purchase | |

| 2 | 1 | Purchase of cars with max. 150 g CO2 emission | |

| Energy intensity | Analysis of indicators to show sources of use | |||

| 2 | 1 | Continuous optimization through the use of frequency/needs controlled pumps, increased use of LED lightening | |

| 2 | 1 | ||

| Waste | Resulting draff and press yeast exclusively used for livestock feed | |||

| 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1 | Favour reusable packaging in purchase |

| Stakeholder | Status Quo | Target State | Measures | Important for... |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | 2 | 3 | Employee benefits, sponsorship of private energy instruments, commuter support | Motivation; solidarity with company |

| Suppliers | 2 | 3 | Favour regional suppliers and products, maintain long-term relationships | Public appreciation, regionality, avoidance of supply problems |

| Customers | 3 | 3 | Intensive personal customer service | Marketing/sales |

| Customer Aspect | Status Quo | Target State | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market share | 2 | 2.75 | Selective, systematic handling of the market of all hierarchical levels |

| Customer satisfaction | 2.66 | 3 | Answer customer problems, regular customer visits, ensure constant high quality |

| Cost reduction and cost efficiency | 2 | 3 | Analysis of cost centers, involvement of employees |

| Employee qualification | 1.66 | 2.66 | Offer professional trainings, keep apprentices after apprenticeship |

| Literature | Case Study |

|---|---|

| Supporting factors | |

| Formation of a project team [5] | Given (CEO, environmental manager, controller, production manager, PR manager) |

| Nomination of a project leader [25] | Given (environmental manager) |

| Employee involvement [25] | Given (workshop, evaluation sheets) |

| Involvement and support of the CEO [8,25,28] | Given (kick-off meeting, interview, evaluation sheets, final meeting) |

| Assignment of sufficient time for strategy analysis [24] | Given (document analysis, discussion in workshop and interview) |

| Limitation of the SBSC’s scope (number of objectives and indicators) [8,24] | Not given (5 to 6 objectives per perspective, approx. 3 indicators per objective) |

| Challenges | |

| Lack of resources [1,8,15,40] | Partly given (lack of know-how and time) |

| Behavioral challenges [25] | Not given |

| Immaturity of strategic management and project management [38] | Partly given |

| Non-existence of a formal strategy [5,25] | Given (not explicitly defined/formulated) |

| Little coordination between departments [8] | Partly given |

| Provision and preparation/treatment of data [5,15] | Partly given (good basis for environmental aspects, no stakeholder analysis) |

| Definition of performance indicators [8] | Partly given (no final selection of proposed indicators) |

| Identification of long-term objectives and cause and effect chains [42] | Partly given (restriction of number of objectives difficult) |

| Classification of aspects as objectives or measures [20,41] | Given (discussions about aspects of the learning and growth perspective) |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Falle, S.; Rauter, R.; Engert, S.; Baumgartner, R.J. Sustainability Management with the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard in SMEs: Findings from an Austrian Case Study. Sustainability 2016, 8, 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8060545

Falle S, Rauter R, Engert S, Baumgartner RJ. Sustainability Management with the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard in SMEs: Findings from an Austrian Case Study. Sustainability. 2016; 8(6):545. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8060545

Chicago/Turabian StyleFalle, Susanna, Romana Rauter, Sabrina Engert, and Rupert J. Baumgartner. 2016. "Sustainability Management with the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard in SMEs: Findings from an Austrian Case Study" Sustainability 8, no. 6: 545. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8060545