1. Introduction

Conducting business in the conditions of the economic crisis has given rise to a new perspective on the decision-making processes taking place in companies. Companies' ability to manage business continuity, including their abilities related to strategic revival or restructuring, is acquiring special significance which should contribute to ensuring the continued creation of company value. This is important in that the management mechanisms of the capital market are significantly influenced by changes in the macro-environment occurring at the same time, forces of sectoral determinants and internal decision-making processes in companies. One of the key strategic factors affecting these processes is to have the appropriate competencies related to company life cycle management using efficient business models. These models, which define and take advantage of the company’s potential to compete, shape the image of the company in the market and are a source of competitive advantage which the company has and renews cyclically. It should be noted that, as [

1] (p. 174) writes, a business model concept is based on economic sciences and paradigms related to conducting business. This insight allows a researcher to expand the scope of research into issues related to the active conduct of modern business. The authors hypothesize that the achievement of success by a company and its ability to build company value over a long period of time depends on having an efficient business model in each period of business activity using sustainability criteria. This model should be appropriate for the present market conditions and should allow the company to adjust to ever-changing needs by managing its configuration in such a way that the interfaces between its components provide a platform for the dynamic development and growth of the company at each stage of its operation.

The purpose of the paper is to present the research findings and discussions in the field of designing business models that contribute to the creation of value at various stages of the business life cycle, and indicates that a business model at the maturity stage of development has the characteristics of sustainability. The paper presents selected theoretical aspects and the findings of extensive research into the business models of companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, as published in works by M. Jabłoński [

2] and A. Jabłoński [

3]. The studies described in these publications have been selectively chosen for the purpose of this paper, as well as combined and interpreted in such a way as to cover all the stages of a company’s life cycle. The same applies to studies and analyses and how they take into account the business models of both companies at the early stage of development and mature companies. Based on the data, the paper presents reflections on and analyses of business models in the life cycle in the context of business model development which fulfills the objectives of the sustainability concept. The managers of companies at the early stage of development focus their attention on designing, delivering scalability and dynamically adjusting the business model used. Conversely, in mature companies they significantly expand the understanding of the business model, adding management intentions to its attributes, based on balancing the interests of different groups of stakeholders and the coherent and coordinated use of assumptions of the Value-Based Management and Corporate Social Responsibility concepts, leading to the creation of the Sustainable Business Model. Business models examined by means of the criterion of the life cycle change due to the growing needs of stakeholders over time. As these needs and expectations are the greatest in the case of mature companies, it is therefore justifiable to create a category of a business model based on sustainability. The methodological objectives of the paper are based on the theory of a systems approach by L. von Bertalanffy [

4], K.E. Boulding [

5], R.L. Ackoff [

6] and the approach of Resource Based View, Rumelt [

7], E. T. Penrose [

8], J. Barney [

9,

10,

11], R. Amit, P., M. A. Peteraf [

12], B. Wernerfelt 1984 [

13], M. J. Dollinger [

14], C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel [

15] (p. 81). The systems approach and resource-based view are suitable for the assessment of business models and company management in terms of the life cycle, as they take into account the pooling of resources in a relatively firm and unified whole. The business model is a system consisting of the fitting configuration of resources appropriate for a given situation.

This paper is structured as follows. After discussing the sustainability concept as a new way of understanding business sustainability (

Section 2), business models are discussed in terms of the life cycle (

Section 3). The literature on issues related to the life cycle and its reference to the concept of business models has been reviewed.

Section 4 deals with the design of business models at the early stage of development, while

Section 5 presents the design of business models at the maturity stage of development. These approaches to designing business models are slightly different as are the assumptions on which they are based. The research methodology is presented in

Section 6, as well as the scope of research, research subjects, and hypotheses for both companies at the early stage of development and mature companies. The research findings are presented in

Section 7 and

Section 8. The discussion is presented in

Section 9. The conclusion in

Section 10 summarizes the core findings of the paper and the core results of the analysis.

2. A Sustainable Business Model as a New Way of Ensuring Business Sustainability

The core premise underlying the concept of sustainability is related to the philosophy of the Triple Bottom Line [

16] which increases the chances of survival in various conditions. Business model sustainability is now one of the key determinants of doing business. T. Dyllick and K. Muff define the evolution of sustainability according to three levels of Business Sustainability, the development of which is presented in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the business sustainability concept, assuming that the formula of “Business Sustainability 3.0” is currently being developed, where the idea is action based on value creation by supplying goods and the organization’s openness to the external environment. Different models, approaches and concepts presented in the literature make the concept of sustainability ambiguous and difficult to interpret. On the one hand, it mentions ensuring business sustainability, and on the other hand, a multidimensional look at the organization considering the interests of various groups of stakeholders. W. Stubbs and C. Cocklin express the view that, in relation to sustainable enterprise, the company should aim to generate income. Profits are used to pursue sustainable goals, as well as the mission and vision based on achieving social and economic objectives and financial performance [

18].

S. Schaltegger and R. Burritt highlight the ambiguous impact of social and environmental attitudes on a company’s financial performance, giving examples in which such attitudes have no effect on the economic success of the company [

19].

T. Dyllick and K. Hockerts present a model based on the concept of corporate sustainability (balancing and integrating the company’s activities) mapped in the form of a triangle. In the three corners of the triangle the focus is, respectively, on the business case, natural case and societal case [

20]. W. McDonough and M. Braungart present the model of corporate sustainability in the form of a fractal triangle with ecology-ecology, equity-equity and economy-economy in its corners [

21].

F. Boons and F. Lüdeke-Freund focus on linking the sustainability concept with innovation. In their opinion, the sustained success of an organization depends on innovation. Rules determining the functioning of a sustainable business model should be based on creating technological innovation that can create new markets after being commercialized [

22].

The relationship between the concept of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) and financial management is highlighted by Archie B. Carroll and Kareem M. Shabana, who believe that generally, based on the review of practical business examples, CSR has a positive effect on company performance [

23].

S. Schaltegger and R. Burritt show that applying the principles of corporate social responsibility and sustainability management uses the same assumptions, based on the integration of social, economic and environmental aspects [

24].

Frank Boons, Carlos Montalvo, Jaco Quist, Marcus Wagner believe that sustainable business models should be supported by government agencies through appropriate policies. Companies and government should work together to create innovations implemented in sustainable business models [

25].

A business case for sustainability according to S. Schaltegger, F. Lüdeke-Freund and E.G. Hansen is the interpretation which indicates that the key aspect differentiating classic business solutions between cases based on sustainability is a primary objective and incorporating smart solutions based on environmental and social factors affecting the economic success of the company into the business model [

26]. J.G. York defines three conditions that guide the investors when they invest in sustainable business, namely the required increase in ROIC (Return on Invested Capital), the minimum value of the WACC (Weighted Average Cost of Capital) and an increase in the availability of capital. This approach is cost-effective and usable for startups [

27].

S. Schaltegger, E. Hansen, and F. Lüdeke-Freund define a business model for sustainability as one which helps in describing, analyzing, managing, and communicating (i) a company’s sustainable value proposition to its customers, and all other stakeholders; (ii) how it creates and delivers this value; (iii) and how it captures economic value while maintaining or regenerating natural, social, and economic capital beyond its organizational boundaries [

28].

Nikolay Dentchev, Rupert Baumgartner, Hans Dieleman, Lara Johannsdottir, Jan Jonker, Timo Nyberg, Romana Rauter, Michele Rosano, Yulia Snihur, Xingfu Tang, and Bart van Hoof solicit inputs on the variety of organizational settings which support the implementation of sustainable business models.

- –

Do organizational and legal structures matter for the development of sustainable business models? If so, how does that help or hinder utilization of the new models?

- –

What are the drivers for profit-dominated organizations to engage in implementing sustainable business models?

- –

How does intrapreneurship impact the implementation of sustainable business models in multinationals?

- –

What is the role of the service sector in implementing sustainable business models, in addition to manufacturing or other types of industries?

- –

Are there conflicts of co-existence among multinational companies which are using sustainable and conventional business models?

- –

What are the dynamics of sustainable business model implementation in non-profit organizations and government-controlled organizations [

29]?

N.M.P. Bocken, S.W. Short, P. Rana, and S. Evans believe that business model innovations for sustainability stand out from other concepts due to the fact that innovations based on reducing the adverse effects on the environment make it possible to effectively capture value from the market and increase the economic value of the company. At the same time, the product offer also changes [

30].

Each approach indicates how interdisciplinary a sustainable business model concept is and how many interpretations it has. It is interesting to examine a sustainable business model from the point of view of the life cycle.

3. The Life Cycle of Business Models

The relevant literature proposes various definitions of business models. This concept is interpreted from different points of view. For example, according to R. Amit and C. Zott, “A business model describes the structure of transaction governance designed in such a way that value is created and all business opportunities are taken advantage of” [

31] (p. 511).

The definition by R. Casadesus-Masanell and J.E. Ricart is based on identifying business logic in the context of creating value for stakeholders [

32] (p. 196).

As far as preserving the continuity of the business in the long term is concerned, the definition of the business model was presented by B. Demil and X. Lecocq, who say that “a business model defines how the organization operates to ensure its stability” [

33] (p. 231). An interesting definition has been presented by B. Mahadevan, who says that a business model is the unique configuration of three streams, namely a stream associated with customer service and cooperation with partners, a revenue stream, and a logistical stream [

34] (p. 59).

D.J. Teece bases his definition on converting payments into profits [

1] (p. 173).

An approach to business models based on the concept of innovation is presented by H. Chesbrough, who claims, based on joint works with R. Rosenbloom, that it is crucial for a business model to rely on assumptions resulting from presenting a value proposition, identifying market segments, designing the structure of the value chain, looking at the means of generating revenue, evaluating the cost structure, as well as describing the company’s position in the value network. All this must be supported by an adequate competitive strategy [

35] (p. 355).

E. Fielt highlights the description of business operation logic in terms of capturing value from the market [

36] (pp. 91–92).

There are many definitions and approaches to business models and there is still no consensus on a universal definition. They are examined in terms of the essence of their definition, the use and the configuration of components. The proposed definition of the business model concept is interdisciplinary in its nature. They prove the broad extent to which the definitions of business models are examined in relation to many areas and perspectives. Some authors focus their attention on the strategic character of delivering value to a customer, others on the results such as profit, and still others on social aspects. The definitions presented emphasize other factors that distinguish them from one another. Undoubtedly, however, all of them focus on the logic of doing business, and thus on the assumptions on which the company has based its business. The distinct characteristics of various approaches to the issue discussed result from showing other features which can ensure the company’s success. Life cycle is an important issue in terms of examining business models.

The issue of a company’s life cycle is generally widely recognized in the literature. Authors who have contributed to the development of this issue include Chandler (1962) [

37], Patton (1959) [

38], Levitt (1965) [

39], Cox (1967) [

40], Churchill and Lewis (1983), Greiner (1972) [

41,

42], Hofer (1975) [

43], Scott and Bruce (1987) [

44], Quinn and Cameron (1983) [

45], and Parnell and Carraher (2003) [

46]. According to Levitt (1965) and Cox (1967), different strategies are adopted at different stages of the product life cycle. Thietart and Vivas (1984) [

47] argue that strategies depend not only on the stage of the life cycle, but are affected by the company’s strategic logic. In addition, the success of the strategy seems to be dependent on the sector and characteristics of the external environment.

In terms of the examination of the life cycle of companies in the context of the organization, from the point of view of business models, a cognitive gap can be observed in this area. To date, the issue of the life cycle of companies in terms of business model attributes and increasing the value of the company has not been widely discussed. The business model as an ontological being may also be examined from the point of view of the life cycle.

The authors highlight the research gap in existing studies, e.g., on strategic factors and interrelations, and derive their research questions. There is a significant research gap in management sciences in the scope of business models in the context of the life cycle, particularly in relation to the companies listed on the stock exchange applying the principles of sustainability.

As regards research into the life cycle of business models, D.R.A. Schallmo and L. Brecht show the relationship between the length of the life cycle and the application of corporate social responsibility principles, which, in a sense, is linked with the concept of sustainability. The authors suggest that the application of corporate social responsibility principles contributes to business model sustainability. These principles lengthen the life cycle of the business model [

48].

Further research was done by M. de Reuver, H. Bouwman and I. MacInnes, who examined which types of external factors are most important from the point of view of the business model life cycle. They argue that, on the basis of 45 case studies from various sectors of the economy, the most important drivers of business model dynamics are technological factors. This is particularly important in the case of startups, where technological attributes should be supported by market needs, while for large companies this relationship is less important. External factors must be taken into account when designing the business model in various stages of development but also when modifying it [

49].

As far as the business model at an early stage of development is concerned, some characteristics can be observed. A business model at an early stage of its development is shaped in the context of applying the effective configuration of components that constitute it, and which are conducive to the creation of value. A business model should be supported by the attributes related to the quality of the management team. This is particularly important as regards the quality of the management of companies at an early stage of their development. B. M. Martins Rodríguez [

50] (p. 129) identifies a need to separate two key areas, namely the business model and the characteristics related to the top management team. A startup can succeed only if managers have high competencies and operational capabilities in terms of creating value.

A business model goes through the distinct stages of the idea, development and commercialization. Its shape is different from what it will be in the future, when, in order to maintain continuity of business, a company will need to use different methods and management concepts appropriate to the level of organizational development. The companies that are at an early stage of development and their business models should be geared to survival. However, the planning horizon in these companies is shorter due to a number of uncertainties. Young companies focus mainly on finding a viable, scalable and effective business model, which will allow the company to capture market value. Changes in such models as regards the company’s configuration can happen very quickly—companies modify their business models throughout the life cycle. Survival is a goal for both young and mature companies, at which point stakeholders will play a greater role, expecting the distribution of the value produced. The final form of the business model will be based on balancing various areas of activity in the form of constructive comparison, which may be referred to as a sustainable business model. The concept of sustainability is understood as durability; sustainability is a relatively new concept not yet fully explored. W. M. Grudzewski, I.K. Hejduk, A. Sankowska, and M. Wańtuchowicz define sustainability as the company’s ability to continuously learn, adapt and develop, revitalize, reconstruct and reorient to maintain a lasting and distinctive position in the market by offering buyers above-average value today and in the future (consistent with the paradigm of innovative growth) through organic variation constituting business models, and arising from the creation of new opportunities, objectives and responses to them, while balancing the interests of different groups [

51] (p. 27). C. Kidd believes that the concept of sustainability derives from a broader look at this issue, in relation to balancing the influence of various political, social and scientific groups in time [

52]. This means that there is a close correlation between the stability of the business and sustainable stakeholder relationship management. G. Svenson, G. Wood, and M. Callaghan also argue that a fundamental aspect of sustainability occurs when company expectations and ideas of the market and society affect the prevailing opinions of what can and cannot be done in sustainable business practice. In turn, stakeholders and their expectations help to answer this question [

53] (p. 338). Relationships with stakeholders determine the shape and nature of the principles of sustainability in business. An interesting sustainable business model based on an original SMART concept (sustainability modeling and reporting system) has been developed by M. Daud Ahmed and D. Sundaram [

54] (pp. 611–624). In this model, they defined the sustainability roadmap (sustainable business transformation roadmap) in which the key elements consist of design, transformation, monitoring and control, discovery, science and strategy. M. Yunus, B. Moingeon, and L. Lehmann-Ortega define the concept of a social business model, which can also be a sustainable business model, and have developed the foundations of building a social business model consisting of two areas also common to innovative models and areas specific to social models. They show similarities with conventional and innovative business models which include:

- –

the challenges of conventional knowledge and basic assumptions,

- –

the discovery of complementary business partners,

- –

undertakings in improving process experiments.

As regards the specific assumptions relevant to social business models, they show features such as:

- –

Encouraging social orientation in terms of profit for shareholders,

- –

Clear, specific objectives for profit for society.

The approaches presented show the essence of the sustainability concept and direct its attention to the continuous ability of the company to remain in the market when the condition of this goal is to have an effective business model at every stage of the life cycle. It should be largely oriented to social objectives without losing the features of a company focused on generating profit. The time taken from the stage of business model development to the achievement of a state characterized by features of a sustainable business model will depend on the particular character of the company, the sector which it operates in, and market volatility. Based on observations of the phenomena occurring in the economy, it can be said that this time grows ever shorter. The ability to understand the cycle designed in such a way allows managers to quickly detect weaknesses in the business model and adjust its configuration to ensure the constant ability to create value, at the beginning mostly only for shareholders, and later also for other stakeholders by adapting it to the expected value. It is possible that, at the initial stage of company development, a business model that has the features of a sustainable business model is built. However, it rarely happens in a free market economy. In its initial stage of development, the company focuses primarily on investing and multiplying profits for further expansion and development. At a later stage of development, the company can share what was gained in previous years.

Figure 2 shows the change in the business model in the life cycle of the company. A business model at an early stage of development will be characterized by features other than a business model in its maturity stage of development. To ensure their usefulness and verify their effectiveness, different management methods and techniques will be used.

Analyzing the approaches to and definitions of business models described in the literature, the authors adopt the approach by Ch. Zott and R. Amit in their reflections on further research. Their proposal is based on the fact that a business model is a package of specific actions performed in order to meet the needs of the market, in particular involving partnerships centered on the focal company and its partners [

56]. The proposed approach requires a focus on how the business is conducted, on how value is created for all business participants and on identifying partners that can assist in performing actions important from the point of view of the business model. It is a holistic approach [

57]. After analyzing the literature, the definition of a sustainable business model in the life cycle has been presented. A business model evolves during the life cycle of the company. In the authors’ opinion, a sustainable business model in the life cycle is a business model that is capable of evolution throughout the life cycle, assuming an incremental increase in the value of the company when the principles of Corporate Social Responsibility and Value-Based Management are adhered to.

4. The Design of Business Models at the Early Stage of Development

Companies are increasingly competing not only on products and/or services, their quality or price, but on business models as well. A company with a profitable business model achieves higher market capitalization, is attractive to investors and stakeholders, and consequently has more market opportunities. Company value depends on the attractiveness of its business model and the skills to introduce dynamic changes therein, resulting from the needs of the environment. The proposed approach to the design of strategies and business models aimed at creating value is related to the configuration of the business model. This means a set of business model components that shape its whole, characterizing the essence of this model. The word “configuration” is used as business models can be altered by modifying their components, and even in some cases totally reconfigured. In this approach, the ontological essence is not so much the business model as this configuration. Dynamics of a business model means its ability to change, which leads to a higher company value than before the change, by using a different configuration of business model components. Issues pertaining to the level of technology, processes and strategies should be included in a measuring system used to monitor the process of creating value. Designing business models requires the ability to respond to any signals forecasting changes in the external and internal environment of the company; managers not taking them into consideration in the decision-making process can lead to economic losses. The business model constantly reacts to corporate strategy. The concept of strategy geometry developed by R.W. Keidal fulfills these expectations, making a clear distinction between elements of the complexity of formulating strategies in the context of the factors that influence them [

58] (p. 6). Changing the business model can be natural (resulting from the company’s flexibility in adapting to changes in its environment—a company changes when the business environment changes) or forced. Forced changes are often restructuring in their nature [

59] (p. 36). This approach to management processes requires the implementation of a results-oriented organizational culture. Therefore, in the process of modifying business models quickly, it is essential to implement the concept of Strategic Performance Management. The assumptions of the concept have been presented by A. de Waal, who says that this is a process that requires company managers to regularly verify the mission, strategy and goals. As a result, these goals are measurable using key success factors and performance indicators to maintain the determined direction of the company’s operations [

60] (p. 19).

A dynamic aspect of business models exposes processes and value chains, but it also significantly affects the shape of organizational structures. The proposed approach should serve to quickly move from one model to another using a different business model configuration. One of the assumptions is considering business models from the perspective of seeking an effective configuration of the company strategic structure to identify such components of the business model that are crucial in the process of the creation of company value. Treating the concepts of business models, especially in the area of their configuration, jointly with the concept of value creation appears to be an important subject today, but one which is not fully recognized as yet, especially in the area of companies classified as innovative.

5. Design of Business Models at the Maturity Stage of Development

The dynamically changing global economy in the era of the intensive development of globalization creates new needs, both in theoretical management models as well as in practical discussions related to the perception of business. This is particularly important in the current economic and moral crisis, the effects of which are visible in most developed countries. It is important to find and/or use the existing management paradigms, the examination and codification of which will provide a platform for the development and growth of companies. By observing and analyzing business trends and the behavior of companies for the past few years, it can be concluded that many business orientations and concepts, whose roots and method of evaluation are often radically different, lead to similar business results. This has happened to the concepts of Value-Based Management, Corporate Social Responsibility, Shareholders, Stakeholders as well as Sustainable Business, and was significantly influenced by the globalized nature of world economies, which resulted in the creation of values on the basis of which corporate business models were built. The strategic behavior of companies and their intercultural exchange led to the creation of new sources and platforms for building competitive advantage, and consequently a stable source for building long-term value. The principles of sustainable development are increasingly appreciated, including in the United States. Transferred to the micro level in terms of the competitiveness of the company, its strategy and by following the principles of corporate social responsibility amid the global economic crisis, they resulted in the creation of a new management concept, namely Sustainability. This can be regarded as Sustainable Development aiming to simultaneously adhere to the principles of ethics, ecology and economy, and may also be understood as the ability of the company to manage quickly and flexibly, focusing on objectives and enabling the implementation of the company mission and vision, taking into account the establishment of competitive advantage on the market. This can be achieved by creating new products and/or services and implementing modern management methods and concepts, the source of which is scientific research and solutions to business practices. Sustainable business is business conducted when concepts of value-based management and corporate social responsibility are used in a systemic way, providing value for company stakeholders.

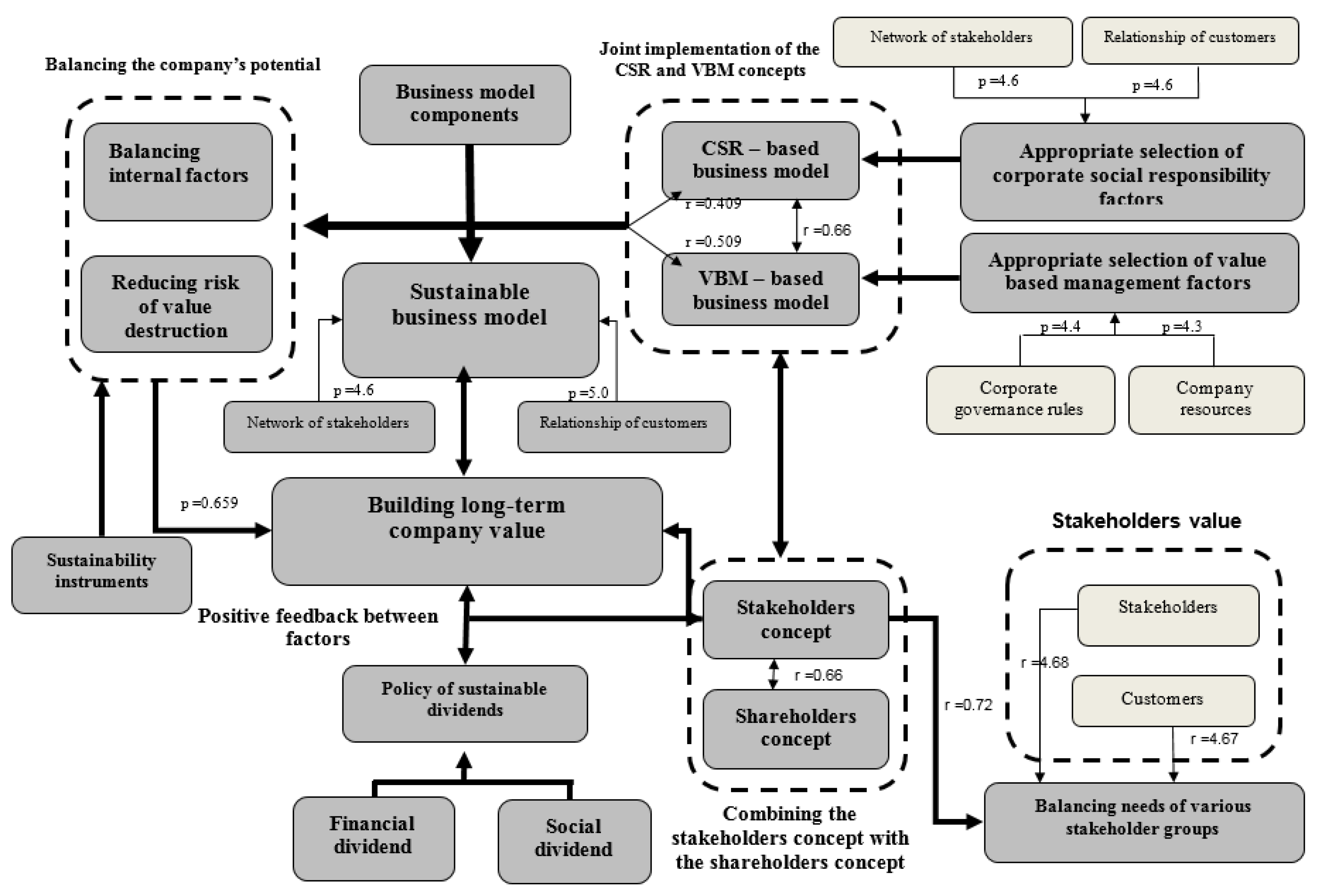

Sustainable business at all levels of management, which includes all of the factors and functions therein, ensures business continuity as well as the power to create value in the long term, and enables a sustainable dividend payout to shareholders and the generation of a social dividend to other stakeholders of the company. The combination of these factors and functions will result in the search for the most optimal business solutions. This can be done through the mutual, constructive comparison of resources and factors influencing the ability to increase company value. Therefore, the most important factor is to find such a balance that will ensure business continuity in the market, while achieving business results which guarantee the long-term value of the company. The balance ensuring the implementation of the sustainable business concept may result from building a sustainable business model connected with the principles of VBM (Value Based Management), CSR and the concepts of Stakeholders, Shareholders and Sustainable Business. This may lead to the continuity of the business in the volatile conditions of the market environment.

Therefore, considering the theoretical and practical dimensions of the above issues, it is important to answer the question, which as yet has not been fully answered in the literature: Which strategic factors and their interrelations in the adopted business models have the greatest impact on the long-term building of a socially responsible company? What should the design of such a business model be?

A premise which says that the subject is important, difficult and requires extended research and scientific discussions is that companies want to build long-term value, to operate successfully in the market, to ensure the continuity of the business, to renew (reconstruct, adapt) their business models, and finally to win. However, they are constantly looking for the optimal ways and mechanisms allowing them to do it effectively and efficiently. At the same time, signals from the market, economic impulses, the economic crisis, chaos in the market, public disappointment with the place and role of companies in the economy, and examples of business collapses all hinder the selection of the most appropriate way to manage companies.

Moving away from certain management concepts, changes in values, the occurrence of the rapid flow of not only capital but also information and knowledge and access thereto, changes in perceiving the nature of the business, and its place in the global ecosystem also resulted in a new dimension in using the strength of management sciences in global business.

According to the authors, new dimensions of business are responsible management, sustainable management, socially acceptable management and efficient and effective management. Such an effect can be obtained by applying sustainability principles in a socially responsible manner.

A socially responsible company is a company whose business model, in increasing its value, is built on the basis of strategic factors associated with corporate social responsibility and the principles of value-based management, while determining wise organizational behavior in the company, and wise market behavior towards company stakeholders, which are based on the principles of integrity, ethics and professionalism.

Strategic factors related to corporate social responsibility and value-based management are the factors associated with the functioning and behavior of the organization towards the external and internal environment, where an appropriate combination leads to sustainable value in terms of long-term operation on the market.

As a consequence of this approach, a holistic sustainable business model is created, reduced in its nature, becoming a platform for creating long-term, sustainable value for a socially responsible company.

A company that is responsible, to a limited extent, is a company that applies the principles of corporate social responsibility only sometimes, when it is clearly profitable. It adheres to these principles not on a voluntary basis, according to the organizational culture of the company, but in a forced way.

A socially irresponsible company is a company that—in its business activities—does not obey the principles of corporate social responsibility by,

inter alia, failing to abide by applicable legal and other conditions, by organizational behaviors indicating discrimination, bullying, intimidation, and other pathological behavior towards staff and other company stakeholders (including suppliers, co-operators and others) and by treating the company and company personnel only as a tool for making profit. In view of the above discussions, it can be assumed that the main components of a sustainable business model built in the subject-object system are strategic factors related to:

A combined implementation of the concepts of corporate social responsibility and value-based management.

Balancing the potential of the company.

Combining the stakeholder concept and the shareholder concept, which are also strongly related to the concepts of corporate social responsibility (stakeholders) and value-based management (shareholders).

A sustainable dividend policy.

A holistic model of sustainable business creating company value in the long term can be built on the basis of the following driving forces that give it the proper dynamics.

Strength of conscious application of corporate social responsibility principles.

Strength of economic sustainability of the company.

Strength of conscious application of corporate governance principles.

Strength of stakeholder value and the dynamics of their migration processes.

Strength of the consensual relationship: company’s board, shareholders, stakeholders.

Strength of implementing a sustainable strategy based on the principles of a balanced scorecard.

Strength of balancing intellectual capital of the company.

Strength of balancing fixed assets of the company.

Strength of balancing internal processes of the company.

Strength of the management style based on the logic of conscious decision-making [

3] (p. 249).

6. Methodology of Research

As a research instrument, one basic method has been used,

i.e., analysis of the literature concerning the life cycle of business models from startup to mature company. The authors present the problem of creating the framework of business models in their life cycle. The level of sustainability depends on the stage of company development. For this purpose, the authors have used literature research, a sustained approach to shaping the attributes of business models, the features of companies at an early stage of development and mature companies, as well as the principles for building a sustainable business model at different stages of company development. The authors have adopted an interpretative approach as the methodology of scientific research, based on the literature and a systematic retrospective assessment of the business models of companies in the course of conducting their own business activity and during their consulting practice. As regards the companies at the early stage of development, the issue of which business model components are responsible for increasing shareholder value to the greatest extent is also important. They should, therefore, be a driver of adjusting business models, and changes aimed at building company value should focus on them. The scope of the issue presented in the paper represents an attempt to link the findings of the research in the context of the business life cycle criterion, namely at an early stage of company development, and at the maturity stage. Therefore, if we add the two scopes of research, quantitative research was conducted on a sample of 220 companies listed on the Polish Stock Exchange in Warsaw (48 New Connect companies, 44 Index WIG20, WIG40, WIGdiv, Respect Index, New Connect Lead companies and 128 companies taking part in the "Environmentally Friendly Company" national ecology competition). Qualitative research was conducted on a sample of 384 companies from the New Connect market and 10 selected companies taking part in the “Environmentally Friendly Company” national competition. The research concentrated on the issue of shaping the business models of companies operating on the New Connect alternative trading system, organized by the Warsaw Stock Exchange, aiming to increase their value; its objective was to design the so-called sustainable business model of mature companies that build value over the long term and that operate on the Stock Exchange, in the following indexes: WIG20, WIG40, WIGdiv, Respect Index, New Connect Lead and companies participating in the "Environmentally Friendly Company" national ecology competition. To study companies at the early stage of development, the component approach by S.M. Shafer, H.I, Smith, I.C. Lander [

61] (p. 202) and work by M. Jabłoński [

62] (p. 39–47) were applied to shape the configuration of the business model. As far as the assumptions of the Value-Based Management concept are concerned, works by A. Rappaport [

63] and T. Copelland, T. Koller and J. Murrin [

64] were used. To study the business models of mature companies, the approach of combining VBM and CSR concepts promoted by J.D. Martin, J.W. Petty, J.S. Wallace [

65] and work by A. Jabłoński [

66] were used. The combination of these assumptions resulted in a coherent approach to examining business models from the point of view of the life cycle criterion. Business models change over time due to the influence of internal and external factors. In the relevant literature, the issue of business model changeability during the life cycle of the company has been studied broadly. Also, no extensive analyses have been conducted on transforming business models from the idea of building a business model configuration conducive to the creation of value, achieving scalability of the business model to obtaining the strategic balance of a holistic nature in relation to different areas.

The comparative table below shows the characteristics of a business model at the early stage of development and a sustainable business model. (see

Table 1).

The study process and its scope are presented in

Figure 3.

The life cycle of a business model is graphically depicted. During initiation and growth, business models of the companies at an early stage of development, listed on the New Connect alternative Warsaw Stock Exchange market, were examined. The maturity stage was examined as regards the companies with a strong market position in WIG20, WIG40, WIGdiv, and the Respect Index indexes. For both research areas,

i.e., the early and mature stages of development, research hypotheses were formulated regarding the impact of various factors on building company value through developing business models. Research findings for both stages of company activity are presented below in

Section 7 and

Section 8.

7. The Findings of the Research on Business Models at an Early Stage of Development

Reviewing the trends in the Polish economy, the authors concluded that the most appropriate place where people use the idea of the business model is the Warsaw Stock Exchange. The New Connect alternative trading market is significant in the process of designing business models that create value in the initial stages of company development. The market has been operating in Poland since 30 August 2007, and commenced operations in a relatively difficult and deteriorating external environment. Despite the adverse conditions, the growth rate of IPOs (Initial Public Offerings) and the financing of their development was very high, through the market of both private and public offers prior to entry onto the New Connect market and thereafter [

67] (p. 5). For the first few years of its operation, the market has produced satisfactory results. The measures of this are that of more than 400 companies listed on New Connect, about 20 companies have moved to the main market since the index was created; issuers in the alternative market have the choice of nearly 100 authorized advisers; the capitalization of all companies listed on New Connect is PLN 9.024 billion; investors may earn as much as 1875% on debut; the record drop in the share value of New Connect-listed companies to date is 99%; and there are three segments of issuers, namely ASO-NCLEAD, the best companies, NC HLR, companies with low liquidity, and NC SHLR, high-risk companies [

68] (p. 37). Analyzing the data, it is possible to surmise that New Connect creates research conditions which facilitate a better understanding of the configuration of business models of Polish companies conducive to value creation. An examination of the business models of companies listed on New Connect in the context of the company value criterion is interesting, as such comprehensive studies have not been conducted to date. No recommendations on the development of these business models have been formulated, either.

It can be assumed that the configuration of business models determines their efficiency, and that skillful and rational management multiplies the wealth of investors. Managers of companies listed on New Connect should be aware of the strength of their business models on the path to the creation of value. They should also know the factors determining their design, modification and adjustment aimed at continually multiplying value for shareholders and the company, and should understand the rules affecting the ability to effectively manage business models. A business model is a kind of system which is composed of many elements, a proper configuration of which should facilitate the achievement of the ultimate goal, which is an increase in company value. The originally set goal has been expanded and new objectives have emerged during preliminary research, namely identifying the methods and tools used by the company in terms of monitoring the value creation process, the degree to which the company is results-oriented and the objective of building systems of value-based management.

The main purpose of the research was to assess the development of business models of Polish companies conducive to the creation of their value. In order to verify this relationship, it was necessary to formulate the following partial hypotheses:

The research sample was companies listed on New Connect at the time of conducting the research (desk research: 384 companies on New Connect), quantitative research (a research sample of 48 companies on New Connect) and qualitative research (12 companies selected from among the 384 companies listed on New Connect on 24 May 2012 which met the criteria of representative companies). Two case studies were developed. Research was conducted from November 2011 to May 2012, and research triangulation was applied. In terms of desk research, 384 companies listed on New Connect were studied. The research model adopted ensured the diversity of the research sample in terms of geography and the type of business. Furthermore, it ensured diversity among the business models used. Analysis was conducted based on public documents:

- −

the information document from the debut on New Connect,

- −

financial statements,

- −

financial analyses carried out by brokerage houses, investment houses and banks.

The analysis included an assessment of changes in the quotations of companies on the market. The companies were evaluated on the day of their debut, after 52 weeks of the floating date (if time of operation on the market was less than 52 weeks, its total operating time on New Connect was taken into account), and on the day the research was conducted. Within the framework of the quantitative research, the sample was selected in such a way that the objectives could be achieved. The companies surveyed were capital companies, mainly small- or medium-sized. Analyzing the territorial scope of activities of the surveyed companies, it should be noted that half of them operate on the international market, 37.5% operate on a national scale, while 12.5% only operate regionally. None of the companies operate only locally, which indicates the high potential and innovative character of their product offer. Therefore, the products and services they offer find both a national and international audience. As part of the qualitative analysis of business models, companies that achieved a positive return at the end of 2011 were selected (their rate of return at the end of the period was positive); moreover, the degree to which they fulfilled forecasts specified in the information document was not less than 90%. This criterion was adopted in order to select, out of all companies listed on New Connect, those companies that were the best in terms of the scope of value creation for investors and, at the same time, which demonstrated their effectiveness compared to their forecasts. A representative sample obtained in this way was used to prepare business models that were favorable to value creation. At the end of 2011, 338 companies in total were listed on the New Connect alternative market. During the period from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2011, only 64 entities achieved a positive return at the end of the period. These companies accounted for only 18.9% of all listed companies. An additional criterion used in the analysis was the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio and the price-to-book value (P/BV) ratio. The criterion for accepting companies for the research project was the requirement of positive values for both ratios. This additional criterion was fulfilled by 36 companies, accounting for 10.6% of all listed companies at the end of 2011. In particular, the assessment of indicators of the degree to which the net profit assumed in financial forecasts had been achieved was adopted. The indicators were compared with the annual updated rates of return. It was also assumed that the company should have been listed on New Connect for not less than six months—which means that its debut on New Connect was before 1 June 2011. In the original version of the concept of qualitative research on business models, it was assumed that the company should have been listed not less than 12 months prior (i.e., its debut was before 1 January 2011). However, after preparing a sample meeting the proposed criteria, it turned out that only 14 companies fulfilled the criteria. It was agreed that this number was too small to conduct research reliably. Therefore, a decision was taken to accept companies with a shorter period of operation on New Connect. Presence on New Connect, which is characterized by very dynamic changes, for a period of six months, and maintaining investor confidence during this time (expressed in a positive rate of return), can provide a platform for formulating reliable conclusions in terms of the business model configuration, conducive to the process of company value creation. Out of all the companies listed on New Connect, 32 companies (accounting for 9.5% of all the listed companies at the end of 2011) fulfilled all the criteria to be accepted for analysis.

When the percentage share of these companies on New Connect at the end of 2011 was compared to the percentage share of companies examined in the NC Index (NewConnect Index), the total share of 32 companies in the NC Index was obtained, which amounted to 16.9%. The value of the percentage share in the NC Index was almost twice the percentage share in total. This means that the capitalization of New Connect companies meeting the criteria was above average. A total of 12 companies were selected for the qualitative analysis of business models, which accounts for 3.1% of all the companies listed on New Connect at the end of 2011. In order to assess the accuracy of the research sampling, the percentage share of those companies on the New Connect market at the end of 2011 was compared to the percentage share of the NC Index companies. In this way, the quantitative share was compared with the capitalization of companies. The total share of these 12 companies in the NC Index was 6.05%, and the value of the percentage share in the NC Index was almost twice the percentage share of the total. This means that the capitalization of New Connect companies meeting the criteria was above average. Being aware of the limitations resulting from the number of companies approved, they were accepted in terms of conducting the research. All 12 companies selected for qualitative research met the criterion of the degree of at least 90% net profit achieved when compared to that assumed in the financial forecasts (the level of 90% was established based on accepting 10% divergence from the expected result). Two examples were selected for the case study analysis: in the first one, an increase in company value was observed and the business model was not changed, and in the second, financial forecasts were not fulfilled and the business model had to be modified (strong pressure from investors and the Warsaw Stock Exchange Board), which resulted in the company changing its configuration and a significant increase in the share price.

There is no doubt that the business model of a company at an early stage of development is characterized by attributes other than a mature business model. Every company goes through different stages of development, which may change due to the specific nature of the business models. The stages may be as follows: conception, development, commercialization, consolidation, and maturity. At the initial stage of company operation are conception, development and commercialization. A business model should be designed in such a way that, at the expected stage of achievements, a unique combination of resources focuses on the value chain. It is also favorable to take an appropriate position in the value network in order to capture value. Moving from one priority to another in order to create value characterizes the dynamics of the business model. Managers’ knowledge of the business model structure and ability to adapt it skillfully develops the ability to create value [

2] (pp. 411–412). The configuration of the business model at the initial stage of company development is based on the basic attributes and is supported with management methods and techniques focused on the concept of project management. The simplicity of the business model should be its strength as, when combined with a unique configuration of attributes, it can lead to a company gaining competitive advantage, which can thus create value for shareholders. The research and analysis conducted allowed us to prove the main hypothesis: Company value is created by shaping the configuration of the business model components. All the hypotheses presented in

Figure 3 are true.

Figure 4 shows the results of research on shaping the business models conducive to the creation of value for companies in the early stages of development (companies listed on New Connect). The numerical values indicate the strength of the correlation between different components and value creation (or destruction). The proposed configuration of the business model components shown in

Figure 3 is the result of extensive literature research related to identifying individual components constituting the structure for describing a business model. The final number of components is a result of the reduction of the components that, based on preliminary research, were not considered by respondents to have an impact on the creation of company value. The research findings indicate the components of the business model configuration that are of significance to the process of value creation for shareholders. The most important components include: customer relationships, value proposals for customers and brands, configuration of unique resources, quality of supplier products, and configuration of the value chain. These components of the business model configuration of companies at an early stage of development should be thoroughly evaluated and strengthened in order to increase the value of these companies. The stronger the correlation between the creation of value and the business model component, the bigger the effect on the increasing value. In addition, product and business model innovation increases the chances of creating value for shareholders. Companies whose business models are characterized by higher rates of innovation have a higher price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) and price-to-book value ratio (P/BV). The price-to-book value ratio shows the attractiveness of the business model used, meaning that the company has a business model with the potential for value creation. Companies that build dynamic measurement systems based on the defined key business model components control the company better in order to increase its value. Defined business model components determine the design of the indicators for monitoring company value. Companies that are characterized by the ability to obtain their net income forecasts achieve increased levels of P/E and P/BV as well as higher annual rates of return.

In order to rate the relationship between a business model (described by means of business model innovation and product innovation) and the value of a P/E ratio and to rate the shape and strength between these characteristics, a statistical correlation was calculated.

Figure 4 shows the correlation results. In order to determine whether there is a correlation between a business model and a P/E ratio and, if so, how strong it is, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (an unloaded estimate of the correlation coefficient r

xy) has been applied; the coefficient measuring the level of a linear relationship between the variables is r

xy = 0.86 for the variables tested.

The figure of 0.86 indicates that the correlation between a business model and a P/E ratio is strong. In addition, the significance of the correlation was determined by calculating the value of the function t for a correlation coefficient. The number of experimental points equals the number of companies listed on New Connect; it is 24.05.2012 and

n = 384. We accept the hypothesis H

o, that there is a correlation between a business model and a P/E ratio, and the alternative hypothesis H

1, that there is no correlation between these characteristics. The value of the t-statistic, which has a Student’s

t distribution is

t = 1.9. The level of significance is

α = 0.05 (standard for the population). We calculate a probability of

p = 0.07. Since

p >

α, we accept the null hypothesis, and we reject the possible alternative hypothesis—there is a correlation between the studied characteristics. (see

Table 2).

Figure 4 shows the data from the 384 companies listed on New Connect with a price-to-earnings ratio and the ranking of the attractiveness of business models in terms of an innovation criterion. It turns out that many companies have a high P/E ratio at a high ranking of the attractiveness of their business model, while conversely, a low ranking in terms of the attractiveness of a business model occurs in the case of many companies with a low or even negative P/E ratio. Therefore, it can be concluded that a price/earnings ratio is a good measure of business model attractiveness and can, in the long term, be used as an indicator thereof.

The result indicates that if we assume that a business model is effective when the degree of financial targets for the future in relation to the pursued strategy is at least 90%, a strong correlation, obtained as a result of research, between the extent to which the forecast net profit is achieved and an updated annual rate of return proves the relationship between a business model and an increase in value. It is possible to select such business models that enable the implementation of both forecasts and the achievement of positive returns.

To rate the relationship between business model components and an increase in company value (rated based on the answers chosen by managers in the survey), values of the mode, the median, and the arithmetic mean were determined for the factors studied. (see

Table 3)

All business model components were then analyzed in terms of the influence of individual components from the subsystem on the business model (see

Table 4). The following factors were rated:

- –

the customer,

- –

value proposition for the customer,

- –

logic of generating income,

- –

organization of internal suppliers and their key capabilities,

- –

competitive strategy,

- –

position in the value network.

The value of the t-statistic, which has a Student’s t distribution, is t = 2.01. The level of significance is α = 0.05 (standard for this population). We calculate the probability of p = 0.06. Since p > α we accept the null hypothesis, and reject the alternative hypothesis—there is the correlation between the studied criteria.

The test for the significance of the correlation coefficient proves the relationship between the studied criteria. The correlation is significant and strong, as indicated by the low probability coefficient. Correlations are statistically significant (at the level of p < 0.1).

The most important stakeholders are located by their impact on the value of the company and their importance for achieving long-term value.

By analogy, it is possible to adjust business models to market leaders (business model benchmarking). (see

Figure 5)

By making dynamic changes in the configuration of the business model, it is possible to adjust it to develop the ability to create value. The results have been analyzed based on this assumption.

Research and analysis conducted on business models of companies at an early stage of development in the context of activity on the capital market have allowed us to draw the following conclusions:

- (1)

Referring to the review of the relevant literature on business models and value-based management, a theoretical configuration of business models was developed. The results indicate that a business model should be a unique form of resources focused on the value chain. It is also favorable to take an appropriate position in the value network in order to capture value. Moving from one priority to another in order to create value characterizes the dynamics of the business model. Managers’ knowledge of the business model structure and its skillful adaptation develops the ability to create value.

- (2)

Based on the research, the importance of the impact of individual components of the business model on company value was determined. The results allowed us to build a business model structure that indicates what the optimal configuration of the efficient and effective business model should be like. The main components were identified, which include the value proposition for the customer, the customer himself and the configuration of the value chain. The key subsystems of these components were also specified, which indicate what configuration, from among those proposed in the theoretical model, works best for managers, in the context of the criterion of company value. These include: in the area of the customer, relationships; in the value proposition for the customer, brand and innovation; in the area of revenue generation logic, the configuration of unique resources; in the area of organization of internal suppliers, the quality of provided services. The model presents the link between the components and their impact on the configuration of the business model conducive to the creation of value. The structure of a business model which is favorable to the creation of value should be consistent and should include the above-mentioned priorities. It depends highly on the configuration of the value chain.

- (3)

The analysis of the correlation of the degree to which the financial forecasts of net profit described in the annual information documents are fulfilled with the updated rates of return of companies listed on New Connect showed a high correlation coefficient at 0.79. If we assume that the efficiency of the business model is verified by the fulfillment of forecasts, the hypothesis that there is a relationship between the business model and the value increase can be proved. Business model configuration management aims to improve its effectiveness, including the fulfillment of expected forecasts, favors the creation of value and is verified with the values of return rates. Fulfilling forecasts, or failing to do so, significantly affects return rates.

- (4)

In order to assess the factors affecting the rate of company value growth, 23 factors were determined, of which the factors that are most important to New Connect companies include:

- (a)

relationships with customers,

- (b)

a full understanding of customer needs,

- (c)

the ability to create unique value for the customer which is not offered by competitors.

- (5)

Having analyzed a designed portfolio of business model innovation and product innovation, it was concluded that as many as 63% of all companies listed on New Connect are characterized neither by an innovative business model nor by innovative products, which significantly affects the performance of these companies and, at the same time, their market value.

- (6)

Companies which were characterized by both innovative business models and innovative products, recognized as models of this market, accounted for only 10% of the New Connect index. If one looks at this phenomenon positively, in the future one in 10 companies on New Connect may, through capital gained on New Connect, build the elite class of companies changing the rules of the game in the sectors in which they operate.

- (7)

Comparing two extreme sets (the first characterized by an innovative business model and innovative products—only 10% of the companies surveyed; the second, characterized by an unimaginative business model and products—63% of companies), the result is not promising. It is necessary to verify either the potential of the business model component configuration of these companies, or specify stricter criteria for floating on the New Connect market, which should include elements of innovation.

- (8)

During further research on the issue of whether there is a relationship between the business model and company value, it was concluded that there is a very strong correlation between the business model evaluated according to the criteria of innovation and the price/earnings ratio, at a figure of 0.86. The correlation between the degree to which financial forecasts of net profit are fulfilled and the average updated annual rate of return is strong and stands at 0.79. The results obtained give a strong message to theoreticians and practitioners of management that investment in innovation and diligent work towards fulfilling financial forecasts translate into the strong creation of value.

- (9)

There is strong pressure from investors and the board of the Warsaw Stock Exchange to ensure that the forecasts published by the companies are reliable, as this significantly affects the modification of business models used by these companies.

The results presented show that the principles of sustainability as regards the companies at an early stage of development and with respect to incorporating them into the genotype of business models of companies at an early stage of development are used inconsistently and only selectively. The situation is different for mature companies where sustainability is regarded as a value driver.

8. Research Findings on Business Models at the Mature Stage of Development

In conducting research on sustainable business models, the main hypothesis and 11 auxiliary hypotheses were proposed. The main hypothesis is that: the joint realization of the concepts of corporate social responsibility and value-based management affects the balance of the company’s potential and how (and whether) the needs of different groups of stakeholders are fulfilled, which, as a result, translates into an increase in the long-term value of the company.

In the research conducted, in order to prove the proposed hypotheses, the principles of triangulation were used. The methodological triangulation applied covered three types of research: quantitative research, qualitative research and research based on the expert method.

The main objective of the research was to create a holistic sustainable business model contributing to building the long-term value of a socially responsible company. The scope of the research covered companies currently listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange, on the following stock indexes: WIG20, WIG40, WIGdiv, Respect Index, New Connect Lead and companies participating in the “Environmentally Friendly Company” competition; 128 companies that adhered to the principles of corporate social responsibility with a strong theme of environmental responsibility participated in the first stage of the research, on the analysis of the results of the “Environmentally Friendly Company” ecology competition. In the second phase, survey questionnaires were sent to 100 companies listed on the Polish Stock Market Respect Index, WIG20, WIG40, WIGdiv and NewConnect Lead. In the first part, the companies completed a self-assessment questionnaire and underwent a competition audit, while in the second part, research surveys (questionnaires) were sent to the companies that voluntarily self-assessed by completing the questionnaires. The return rate was 44%, which is a satisfactory result. The research sample was selected so that it would fulfill the objectives included in the subject of the paper. The selection of the Respect Index companies, which included companies operating in accordance with best practices in information governance, corporate governance, investor relationships, CSR policy, environmental management, personnel policy, and management systems, aimed to receive answers from companies which consciously follow the principles of corporate social responsibility. The Respect Index companies satisfy the strict requirements of corporate social responsibility, pursue corporate responsibility strategies, or follow an orderly plan of action in terms of company social responsibility/sustainable development. This strategy is created based on business objectives, taking into account the key risks (specific and industry) and results from the need to examine the needs and expectations of significant stakeholder groups. It is pursued on the basis of the schedule adopted and performance measures (results, benefits). The Respect Index is an index of socially responsible companies in Central and Eastern Europe, which includes companies from the main market of the Warsaw Stock Exchange in its portfolio and is one of the indicators that builds their credibility in the eyes of investors. A key element of the business model of the Respect Index companies is an increase in their value, taking into account the principles of corporate social responsibility and the needs of stakeholders.

Questionnaires were also sent to the largest listed companies, that is WSE WIG20 and WIG40 companies, in order to examine these companies in terms of the application of corporate social responsibility and value-based management principles. To fully supplement the sample so that it met the criteria related to all hypotheses assumed, a survey questionnaire was also sent to WIGdiv companies, which is the revenue index (dividends and subscription rights taken into account). WIGdiv comprises the largest companies with high liquidity, which regularly pay dividends to shareholders. The index also includes certain WIG20 companies. The selection of companies in the index was determined by the specific character of these companies, namely that their business model is based on generating profit and regularly paying dividends to shareholders, and focuses on observing the rules of so-called sustainable dividends, which are consistent with the principles of sustainable business. Due to the fact that there is an important correlation between the adopted company business model and its stock index, companies of this index are also included in the research sample.

On the other hand, engagement in corporate social responsibility was also important in the selection of companies. Research was also conducted on 128 companies participating in the Environmentally Friendly Company ecology competition, which promoted the principles of environmental responsibility and sustainable development by creating effective strategies built on ecological criteria.

The research was extended further with the qualitative analysis of 10 companies whose profiles matched the companies from the area of quantitative research, i.e., Respect Index, WIG20, WIG40, WIGdiv and New Connect Lead companies. Ten joint-stock companies were selected, all of which implement corporate social responsibility principles in order to increase competitive advantage and build long-term value. At the same time, these companies, in addition to fulfilling the criteria of ecological responsibility, met the fuller and broader criteria of corporate social responsibility.

The selection of the research sample was as follows:

To achieve the main objective of the study related to the achievement of the expected and assumed state, which is developing a holistic model of sustainable business contributing to building long-term value of a socially responsible company, surveys as well as expert studies were conducted using an evaluation questionnaire and analytical studies of existing documents related to the Respect Index stock exchange. A research criterion for choosing research companies was developed, and the analysis was conducted in terms of both subjective and objective criteria. As regards the subjective criterion, all forms of business activity in Polish legislation were analyzed: sole traders, partnerships, general partnerships, other partnerships, corporations (limited liability companies, joint stock companies). As far as an objective criterion is concerned, after reviewing the literature and business practices, evaluation criteria were defined that aim to properly select the profiles of the companies surveyed. These criteria include: company valuation (a company is subjected to valuation), the pattern of management “best practices” (it may be considered that the adopted management mechanisms, and the degree to which modern management methods and concepts are used, exceed standards in the Polish economy), a minimum market presence of 10 years (the maturity stage in business—in the author’s opinion, a minimum 10-year presence in the market indicates that the company wants to continue its business activity, develop, gain competitive advantage, ensure business continuity and build the long-term value of the company), the principles of corporate governance are fulfilled (a company wants to operate in accordance with the standards of corporate governance, wants to conduct direct and indirect dialogue with shareholders through their representatives in the supervisory board of the company, wants to seek the most effective forms of communication, dialogue and relationships to achieve satisfactory performance), social responsibility is observed (a company which fulfills the principles of corporate social responsibility and includes them in the principles of doing business, wants to balance the interests of major groups of stakeholders and wishes to observe the law, follow core values, care for the environment, and generate profits for shareholders by building an organizational culture that helps achieve this goal), functions in various sectors of the economy and services (companies operate in different sectors, therefore the picture of the study will have a cross-sectoral dimension and the solutions developed during the study and the design of a business model have a chance to be applied in various sectors of the economy and services). (see

Table 5 and

Table 6)

8.1. The Company’s Business Model Based on Fulfilling the Assumptions of the Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility

Companies’ application of the assumptions of the concept of corporate social responsibility has its own internal reference because it is based on ethical principles within the organization, that on the one hand affect decision-making systems, and on the other hand the external environment of the company, shaping its social dimension and image in the market. The conscious application of CSR assumptions was the first area studied of the activity of companies that agreed to take part in research. (see

Table 7)

Figure 6 shows the correlation results. In order to determine whether the assumed correlation between organizational cultures based on CSR and VBM exists and whether it is strong, Pearson’s coefficient was applied to the values (unloaded estimate of the correlation coefficient r

xy); it is a coefficient determining the level of a linear relationship between the variables. The calculated coefficient is r

xy = 0.66.

It can be inferred from the calculation that the relationship is strong, but its significance is determined by the results of the t-test for the correlation coefficient. The number of experimental points is n = 44. We accept the null hypothesis Ho, that there is a correlation between CSR criteria and VBM, and the alternative hypothesis H1, that there is no correlation between the criteria.

The value of the t-statistic, which has a Student’s t distribution is t = 2.3. The level of significance is α = 0.05 (standard for this population). We calculate the probability of p = 0.06. Since p > α, we accept the null hypothesis, and therefore we reject the possible alternative hypothesis—there is a correlation between the studied factors.

The test for the significance of the correlation coefficient proved the relationship between organizational culture criteria based on social responsibility and value-based management. The correlation is significant and strong, as indicated by the low coefficient of probability. Correlations were statistically significant (p < 0.1).

Subsequently, a statistical relationship between corporate social responsibility and balancing the potential of the company was calculated, as well as between value-based management factors and balancing its potential. In order to determine whether a correlation exists and, if so, the strength thereof, Pearson’s coefficient was applied to the values (unloaded estimate of the correlation coefficient r