1. Introduction

This paper is meant to be positioned within the discourse on whether welfare can be achieved with or without growth. The debate has been emerging as a response to the dominant neoclassical paradigm in both scientific debates on economics and Western market economies with their goals of continuous growth and maximized efficiency as a means to achieve wealth in a world of constant competition and rational utility maximization. As a response of the perceived failure of capitalist economies and their underlying ideology, which overstrains natural resources and harms social cohesion, there has been an ongoing debate on sustainable development, questing for a “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [

1] (p. 41), with its milestones of the World Commission on Environment and Development’s report “Our Common Future” from 1987 chaired by Gro Harlem Brundtland and the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio in 1992. Both stressed the need to step away from a narrow understanding that development in low- and middle-income countries could be achieved by means of constant economic growth, towards an interpretation of problems as interplay between economic, social, and ecological factors that consequently need to be jointly addressed.

However, the very possibility of achieving prosperity with growth—being still one of “three pillars” of sustainable development—was criticized for maintaining harms to the natural environment and reproducing resource conflicts. Consequentially, the possibility of growth as a principle for the benefit of human welfare was denied fundamentally by some of the literature: As an alternative, the concept of “sustainable degrowth” with its core attributes of scaling down production and enhancing ecological conditions in order to increase human welfare was developed [

2,

3,

4,

5]. By changed consumption patterns, replacing GDP from its dominant position in political discussions, and decoupling material and energy use from growth, a transition from “more” (i.e., quantitative) to “better” (i.e., qualitative) progress in terms of technological improvements and knowledge increase is hoped to be achieved [

6]. The (from a neoclassical point of view) seeming paradox of living better by both less consumption and less human-caused harm to the natural environment was referred to as a potential “double dividend” of an economy based on principles of degrowth [

7]. In a similar way, the concept of “post-growth economy” suggested the promotion of a lifestyle of sufficiency, regional supply-chains and the development of alternative property and monetary structures [

8].

Being critical regarding the harmful consequences of the conventional neoclassical growth paradigm, some of the literature has tried to recognize the potential benefits of growth for human well-being while trying to eliminate its unsustainable practices. The idea of “green growth” proposed to enhance qualitative growth and to improve the situation of the world’s poorest by promoting a “Green New Deal”. Its goal is to prevent undesirable outcomes by setting incentives, enabling growth within increased efficiency and circular flows of resources, and decreasing carbon dependency [

9,

10,

11]. However, the possibility of decoupling growth from its harmful consequences was questioned again by degrowth and post-growth scholars, thereby making reference to rebound effects which more than superseded gains in terms of efficiency [

3,

8], while the literature on degrowth was partly criticized for being confusing because of its ambiguous understanding in multiple branches [

12].

Generally, the debate seems to be driven by the focus on “growth” and possible ways to limit or escape its harmful symptoms, while one gets the impression that too little attention has been put on discussing its underlying principles. One might suspect that this leads to an underestimation of the complexity behind ideas of how to transform today’s growth-based systems. It is surely necessary to develop alternatives for the dominant economic model when its grievances are considered as predatory and harmful for both social cohesion and the natural environment. However, one should ask why the dominant model has been so persistent and on what principles it is based in order to elaborate more detailed possible reasons for the difficulties in subordinating growth under welfare in today’s economic systems. This article is meant to contribute to this perceived shortage in the debate by attempting to focus on these underlying principles. It presents the results of a qualitative study about the foundations of the German healthcare system. The healthcare system is a distinct area, as it can be seen as one of the major achievements of welfare in modern societies. Having started with a broad research interest in the area of “sustainability in the German healthcare system”, the study eventually turned out to develop a conceptual understanding of the logic behind the healthcare system by applying Grounded Theory Method (GTM), a method used to increase theoretical sensitivity and to aid understanding in a given area of interest [

13]. Its final results were the discovery of two conflicting and yet interdependent basic ideas that can be regarded as constitutive of the German healthcare system. They also allowed the findings to be placed within the wider context of the debate on growth and welfare.

In order to clarify its scope, it is helpful to contextualize the article with regard to the multiple streams and directions that have been emerging around the terms “sustainability” and “sustainable development”. For this paper, the understanding of sustainability as developed by John R. Ehrenfeld was chosen [

14,

15]. His idea of “sustainability as flourishing” suggests turning away from “technocratic” understandings of sustainability that assume it to be a manageable process based on measurements and a set of analytic rules, and towards the formulation of visions of a desirable future state which can be assessed as being present or not in an intersubjective discourse. In order to achieve these desirable states, however, the concept postulates that the cultural systems at the roots of societies need to be understood in order to exchange their underlying values for new ones. Considering the previous thoughts on the necessity of a more profound debate about the underlying causes behind phenomena in the debate on growth and social welfare, Ehrenfeld’s approach seems to be a well-suited match for the scope of this article. After this clarification, the next section offers more insights by describing how the process of gathering and analyzing the data was carried out.

3. Results: Two Dialectic Basic Ideas

The observation of constant contradictions within the areas of financing, providing, and regulating the healthcare system was a phenomenon in the data which eventually became the core of the interpretation. They became obvious through contradicting goals that stakeholders had of how to change the healthcare system, and the procedures and strategies of how to achieve these goals. In the process of abstracting and compressing the data, it was decided to interpret this dichotomy as the expression of two basic ideas.

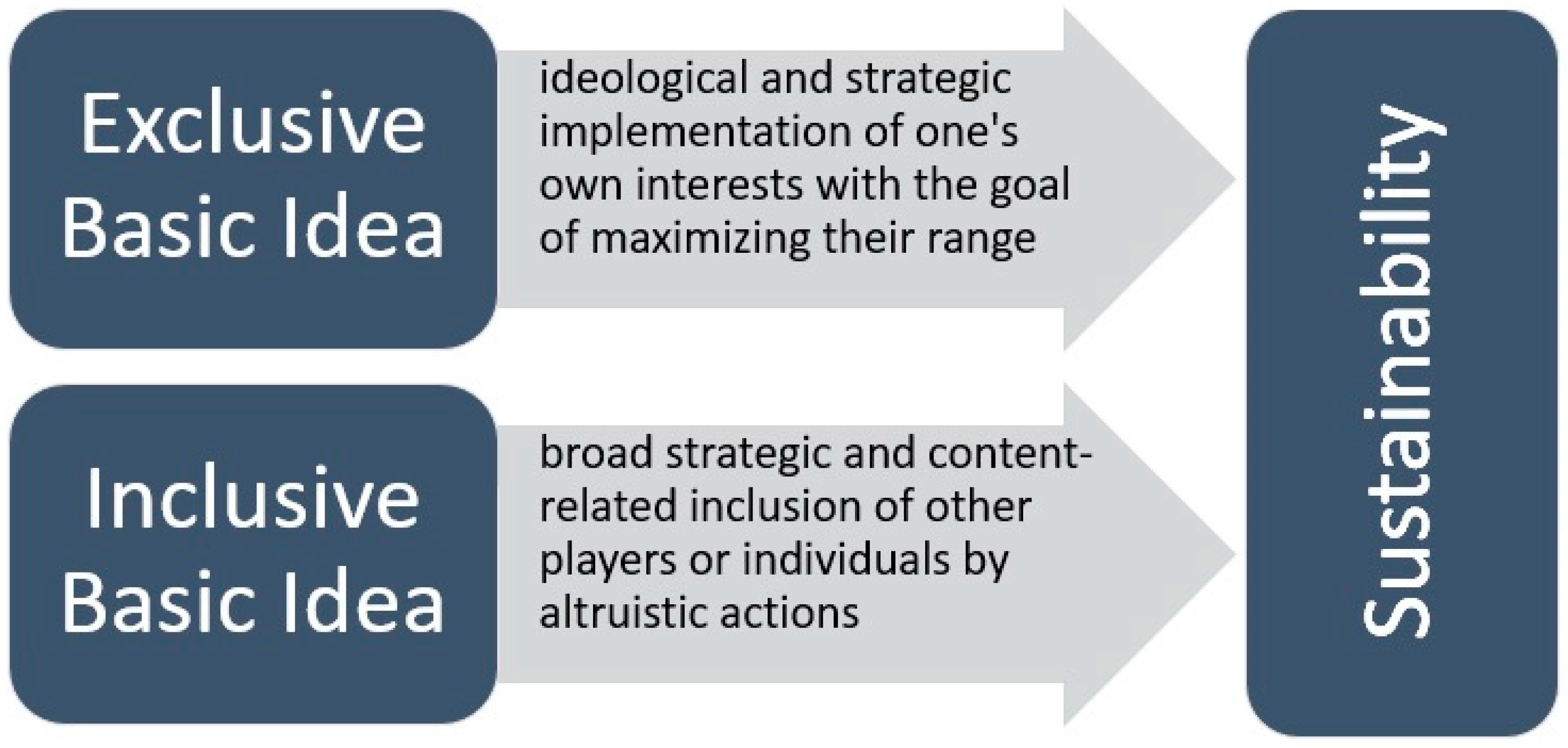

The first basic idea is related to the individual self, which is why it was labeled as “exclusive basic idea”. The exclusive basic idea describes the ideological and strategic attempt to implement one’s own interests with the goal of maximizing their range. One may subsume confrontative strategies, the quest for economic success or, more general, the interpretation of the healthcare sector as an economic factor under this category. This is why the connection of this basic idea with a pure economic understanding of sustainability as opposed to its social and cultural aspects could be assumed. In the concrete data, this could, for example, be expressed by the attempt to prevent the respective opponent from receiving assessments which are too benign and could potentially reduce one’s own performance: “Surely, one does not want that the competitor is in the positive spotlight here but one wants to step on the brake and emphasize the own achievements” (interview 1, (minutes) 28:45–29:03 (of the recorded interview)). That this attitude does not result in a harmonic environment due to potentially major disagreements could also be found in the data: “The healthcare providers are incredibly at odds with each other as they are constantly fighting for their competencies and their demarcation” (interview 8, 35:09–35:18). The conflicts were described as very intense and as a fight producing winners and losers: “They fully drive against it. And then one will see at the end who won, who asserted oneself with his ideas” (interview 9, 18:13–18:22). This lead to the necessity of constantly observing the opponents’ actions: “Actually, we have to guess in advance what is their next idea” (interview 9, 31:00–31:04). Generally, the enforcement of one’s own position was seen as the main goal of the struggle, as a self-critical remark of a lobbyist showed: “In the past, there was often a behavior where the (pharmaceutical) industry called for positive conditions and said: We need them, otherwise something terrible happens. So: We need them—period!” (interview 5, 31:39–31:59). The focus on maintaining the economic contribution of the healthcare system and its interdependence with the whole economy was seen as one of the main reasons for restricting expenses: “And when we always hand the better and better medication to more and more people, our expenses grow out of hand and we need to take higher contributions, which we do not want as this burdens our wage labor costs” (interview 2, 29:10–29:23). Another interview partner summarized the same phenomenon in frustrated terms: “In the end, the conflicts are over and over again about money” (interview 3, 35:11–35:15).

The second basic idea can be described as an idea aiming at including others, which is why it was named the “inclusive basic idea”. The idea is expressed by the broad strategic and content-related inclusion of other players or individuals and by altruistic actions as well as cooperative patterns of policy-making. On a very general level, the interpretation of the healthcare system as a genuine social entity would be subsumed under this idea, which might be connected with a socio-ecological understanding of sustainability which would not take the economic understanding into account. For example, the following quote was seen as an example of justifying cooperative action: “It makes no sense to see it exclusively from the personal or the own party’s perspective. Rather, one always has to ask: How does the other one finds himself there?” (interview 1, 11:18–11:36). The same person outlined an example of what a cooperative strategy could potentially look like: “That one just says: Guys, let’s meet and ask: Can we have a bit of a look here and there?” (interview 1, 29:39–29:50). Similarly, the attempts of interest groups to include the respective opponent were also attributed to this basic idea: “What would a solution look like, a solution which is, then again, also in the interests of the others?” (interview 5, 31:57–32:02). Even in political macro-structures, for example, the relationship between the Federal States and the Federal government this idea was observed, when “the Federal Government normally includes the Länder at a very early stage, especially with bigger projects” (interview 4, 19:49–19:57). Similarly, the idea became obvious in seeing health politics as a means to serve all members of the society without necessarily taking economic imperatives into account: “A health policy which is really based on the needs and really secures that it is in the general interest, which is independent of what you are and where you are. Everywhere in fact. That does not sort, that is accessible, for everyone, so this is what I imagine there” (interview 3, 38:24–38:43).

It is important to note that the results would state that in the empirical world, both abstract basic ideas are expressed by several concrete ideas, strategic-procedural principles, and institutional arrangements. Intuitively, sustainability scientists would probably prefer the inclusive basic idea because of its altruistic and society-oriented nature. The exclusive basic idea, on the contrary, might be equated with a lack of solidarity as well as with neoliberal greed and egoism. However, moral attribution should not be a category in observing politics. Although all players may be aware of the intuitively higher legitimacy of joint actions and social benefits, the quest for maximizing their own position opens a freedom of action for the benefit of others. For example, hardly anyone would deny that doctors that have sworn the Hippocratic Oath are a benefit for society. However, one should not neglect either that doctor’s offices are economic entities that—although they may be strongly regulated by state authorities—have a strong interest to maximize personal income. Being driven by an exclusive basic idea and taking care of the own benefit in the competition with other doctors or hospitals is the basis on which doctors can care for others. However, pursuing one’s individual benefit exclusively would not work either, as this would not take into account that doctors are embedded within the systemic structure of the healthcare system with its closely interconnected and mutually interdependent actors. Another example on a more general level would be the financial environment of the German healthcare system: the system is financed (mainly) by social contributions that are dependent on sound economic performance based on consistent growth rates. By ensuring stable economic growth, politicians are contributing to the financial sustainability of the German healthcare system, which undoubtedly provides society with enormous social benefits. Again, both basic ideas seem to be closely tied.

Thus, this article defines the German healthcare system as a system of needs related to health which is constituted by a constant contradiction between an inclusive and an exclusive basic idea. Both are present and necessary for the system in order to function. The social always defines the economic momentum, inclusion always defines exclusion, and on the very basic level, the relationship of players to themselves always defines the degree of their relationship to others. Both basic ideas exist on their own; they are contradictory and yet depend on each other. They produce the dynamics in the healthcare system and in health politics, which can be seen as arenas of a permanent struggle based on the two abstract basic ideas.

4. Discussion

As stated in the beginning, this article is supposed to be a contribution to the debate of whether social welfare can be achieved without economic growth. Considering the results on the German healthcare system and its regulatory framework which were just presented, what would be the implications both for the research on the German healthcare system and the debate on growth and welfare?

This article sees the healthcare system as a system of needs related to health which is constituted by the constant presence of contradictions between an inclusive and an exclusive basic idea (

Figure 1). The results complement the existing empirical literature on the functioning [

17,

18] and output-oriented analysis [

29] of the German healthcare system with a component that is more about the logical-philosophical essence of the system. Rather than looking at their economic capability or their potential to increase social assets, policy discussions could now be analyzed in a more differentiated way by checking to what extent strategies and contents within the healthcare system are more or less driven by one of these basic ideas. The assumption would be that hardly any decision is purely driven by one of them, as black and white phenomena rarely capture the reality of human structures. Thus, clarifying the standing of one idea will often implicate the extent of which the other one is present. This could be the starting point for further research: In conducting further analyses, the following pragmatic four-step procedure might provide an appropriate help to orient oneself in the complex research on healthcare systems. It is a successive heuristic suggested for structuring further research which is composed of well-known existing concepts and the two basic ideas. When analyzing a decision, one could, as a first step, ask whether this decision affects the way healthcare is financed, provided or regulated, which are the usual constituents in the analysis of healthcare systems [

30]. The second question would be if the decision targets structures and institutions (polity), the struggle for power and the applied strategies (politics) or the actual content and results of the struggle (policy). Because of its elaborated terms, the English language provides a very clear understanding of political terms here as it differentiates between these three, while, for example, in German the notion “Politik” can cover all the three meanings [

31]. The third differentiation would be the level of analysis [

18]: research can focus on the micro-level when the main unit of analysis is the level of the individual. Meso-level, in contrast, refers to groups of actors or collective negotiations, while the macro-level targets procedures on the highest level. Of course, research can also refer to multiple levels in a multi-level analysis. Which basic idea is to what extent expressed by concrete decisions could be discussed as a last step. This could be the starting point for assessing which factors contribute to a higher degree of inclusive or exclusive basic idea in certain healthcare settings, for example by applying the method of Qualitative Comparative Analysis by Ragin [

32]. One could also look backwards in history and check to what extent one of the ideas may have been present or even dominant in a given historical or political environment.

What could be the implications for the debate on growth and welfare? One might argue that, although the healthcare system might be a distinct area of contradictions, the two basic ideas do not need to be restricted to the healthcare system only. One could assume the entanglement between, for example, the economic and social values for all parts of the society holistically and treat the two ideas as being at the core of today’s bourgeois-capitalistic societies. In spite of the same goal of a more sustainable future, one might then argue differently especially than the literature on degrowth in the debate on growth and welfare. In doing so, three points shall be addressed in particular. It shall be done by having a look through the lenses of industrialized-bourgeois societies here, which has a different focus than, for example, discussing the implications on a global level.

The first point is that, as it is hard to separate the social from the economic perspective, the economy cannot just purely serve social and collective purposes in the socio-economic structures as we face them today. Although “growth” may serve as a good symbol in discussions on the brutal excesses of a greed-driven capitalist economy, this would neglect that growth is deeply embedded in bourgeois society as a whole, which after all could be regarded as the expression of the exclusive basic idea, if not the principle of individual liberty up until now. Additionally, this may be the core explanation for why it is not an easy task for highly industrialized societies to agree upon the seemingly logical, i.e., implementing concepts like degrowth with its core suggestions of changed consumption patterns and sharing their wealth out of ethical considerations. Consumerism and the quest for material growth are an expression of a deeply embedded basic idea.

Second, there are good reasons for fighting the excesses of this capitalist system which have been emerging with the promotion of neoliberal ideas. However, the alternatives that the degrowth and post-growth community have elaborated do not seem convincing as they have not reached a status higher than the niche level [

33]. The reason for this might be that options that are based on different ideas are just not immanent to the system yet. Growth is not an instrument that could easily be replaced by a more favorable principle while keeping the social and power structures as they exist today. It is also not just about addressing some leverage points [

34] and “switching on” the age of sustainability. It is most likely that a fundamental change in our way of living would be necessary—most likely in conjunction with a quasi-revolutionary and fundamental re-arrangement of power structures [

35]. But societies and decision-makers would have to clarify: Who would be a legitimate decision-maker on this question? Would people in different areas of the world be ready to accept a restriction of freedom if environmental concerns require them to do so? Would a totally new governance system be necessary, probably on the global level, in order to meet the tremendous challenges? What would be a legitimate composition of it? And would country-specific concerns be respected in such a system?

Facing these challenges, one is tempted to reject the thoughts as possibly unrealistic or overly ambitious. Still, also scientists who do accept the system-immanent role of growth have to question themselves and to look for possibilities of change, as both the literature on degrowth and green growth do make a strong point in outlining the harmful consequences of solely maintaining the status quo. In other words: What could be the concrete conclusion considering the “reversed sustainable development”, as the challenges that are placed on modern societies “develop” (and increase) in an extraordinary manner, whereas their governance and social structures remain “sustainably” stable and do not seem able to adequately adjust and respond to these challenges?

One could argue that exclusive basic idea always carries an inclusive momentum in itself. This might allow us to reflect upon suggestions of terminating and preventing the excesses of today’s economies and to think within today’s socio-structural framework which growth a society aims to have. For example, Jakob and Edenhofer [

36] suggested to encourage growth dynamics that increase welfare (e.g., expenses for education and health) and to prevent growth that diminishes welfare-relevant assets (growth that harms social capital or the natural environment). Alternatively, Cristina [

37] suggested to embed growth within a “saferational approach”, where growth is to be balanced by several rationality- and safety-related factors. Thus, the article would be positioned within approaches targeting qualitative growth. What could be the role of sustainability here? This leads to the third point, where a discursive approach (rather than an implementation of measures by force) is suggested. It is not realistic to understand “sustainable development” as a set of policies that could just be implemented and solve the problems of all social subsystems once and for all. However, having the concept of Ehrenfeld in mind which was presented in the introduction [

14,

15], one could take some of its basic characteristics that are capable of consensus and make them serve as a lynchpin for tackling the excesses of the bourgeois-capitalist system within the current socio-political framework. More specifically, one could understand sustainability with its positive core values of a long-term strategic approach of policy-making, transparency, and participation [

38] as a new frame for a societal discourse, as a platform on which basic value decisions that are caused by conflicting basic ideas are negotiated. This could, for example, imply the discussion of—again referring to the suggestion of Jakob and Edenhofer [

36]—a set of minimum social standards which is financed by welfare-related capital stocks. Political actors could be part of this platform as well as members of the civil society, of science, and media representatives, as the inclusion of a variety of actors is seen as an essential part on the way to a sustainable future [

39]. Policy-makers would have to design an institutional arrangement that is an authentic representation of the different preferences within the current societal framework. The platform could prepare political decisions and develop recommendations for how to diminish the excesses, for example, by effectively preventing supra-national companies from externalizing costs to the general public. Furthermore, they would be in charge of intellectual capacity-building by providing a comprehensive educational policy which is capable of mirroring the different value preferences and their respective (dis)advantages [

40]. First attempts from transdisciplinary research of how to compose these arrangements can already be observed [

41,

42,

43]. They have currently, however, not moved far beyond the local level. Here, the development of further scientifically-grounded approaches of how a platform in order to discuss societal value discussions could look like and what competencies it would have with practical feasibility seem necessary.

Of course, the applied study design as well as the produced results face several limitations that need to be discussed. The first limitation refers to the method’s inherent difficulty in preventing researcher-induced bias. Generally, following GTM means avoiding a priori assumptions about what to find in a given research setting, and—to a certain extent—to find one’s own way of telling a story from dialoguing with the data [

44]. Similarly, conducting exhaustive literature review before the study is generally not recommended as they may bias the following analysis. In fact, researcher-induced bias can be seen as specific to qualitative research as a whole, especially as the author of the study has been dealing with German health politics within the specific university setting throughout the past couple of years. However, in order to decrease possible biases, the obtained results were discussed regularly in group meetings and with colleagues. Furthermore, as it is a strength of the emergent and flexible approach of GTM to foster creativity, the minor importance of standardized procedures, the variety of directions within the GTM discourse as well as the general openness of the conducted interviews may raise questions concerning the validity and the reliability of the produced results. Although this may be perceived as a general problem of qualitative research, an effort was made to outline the applied method of analysis as well as the emergence of the two core categories in the process of analyzing the data in detail in the method’s section of this article in order to grant for a certain degree of intersubjectivity. The last major limitation of the study is the results’ high degree of abstraction, which is why their applicability in real-life settings might be questioned. Although this seems to be again inherent to the method as it does seek to produce theoretical–conceptual insights, one has to admit that the immediate potential to present them in a way that is usable to practitioners seems difficult, on the one hand. On the other hand, this very step aside from immediate practical solutions could be interpreted again as an advantage. Referring to the definition of sustainability as trying to move away from the symptoms towards the analysis of the deeper roots of problems, this again could inspire more applied approaches to make more concrete suggestions of how to design solutions.

As a final remark: In order to be an effective trigger for change, the scientific discourse on sustainability depends on arguments and a broad debate that takes different opinions into account. In order to provide a trenchant presentation of its points, this article can be especially seen as a response to the literature on degrowth and post-growth [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The article questioned the possibility of exchanging growth by these concepts without risking unforeseeable consequences, as they currently seem to lack explanations of what this would mean for basic values like individual freedom or granted property rights as well as the growth-based financing of the social state. Based on the results of research about the German healthcare system, it argued that growth must be seen as the expression of an exclusive basic idea that is deeply embedded in the foundations of bourgeois-capitalist societies. As a consequence, it suggested that it is more preferable to think of which growth is desired in a public discourse and how it can be achieved within a given framework. In order to grant for a differentiated debate, sustainability could headline a platform for exchanging opinions and preparing political decisions that affect our common future. However, sustainability scientists need to develop ideas for institutional arrangements with a chance for substantive realization, which is why further transdisciplinary research including politicians and actors from civil society is needed.