Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Investigate Purchase Intention of Green Products among Thai Consumers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

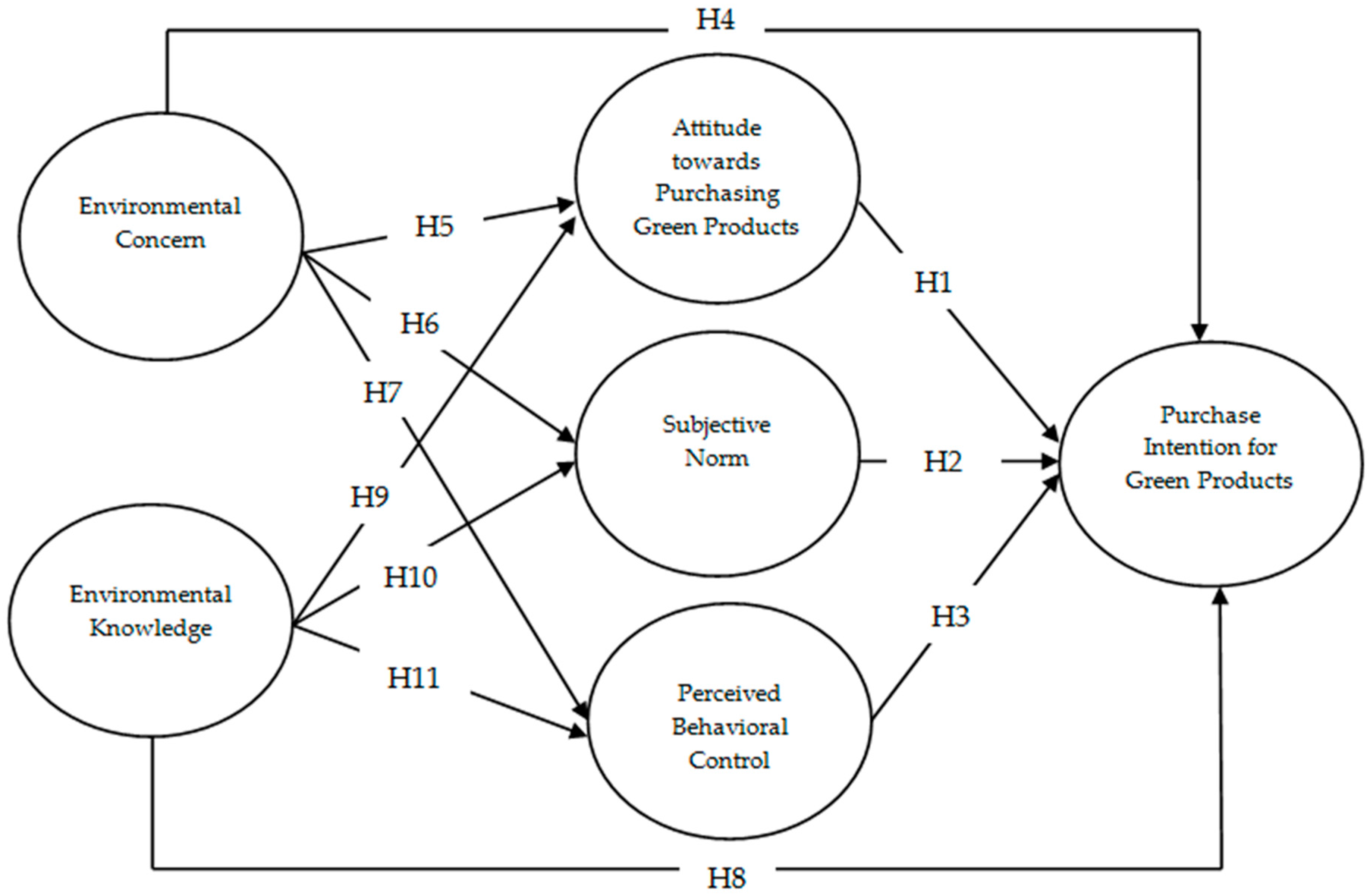

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Green Products

2.2. The Components of the Extended TPB Model

2.2.1. Attitude towards Purchasing Green Products (ATT)

2.2.2. Subjective Norm (SN)

2.2.3. Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC)

2.2.4. Environmental Concern (EC)

2.2.5. Environmental Knowledge (EK)

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Tools for Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Testing of Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Model

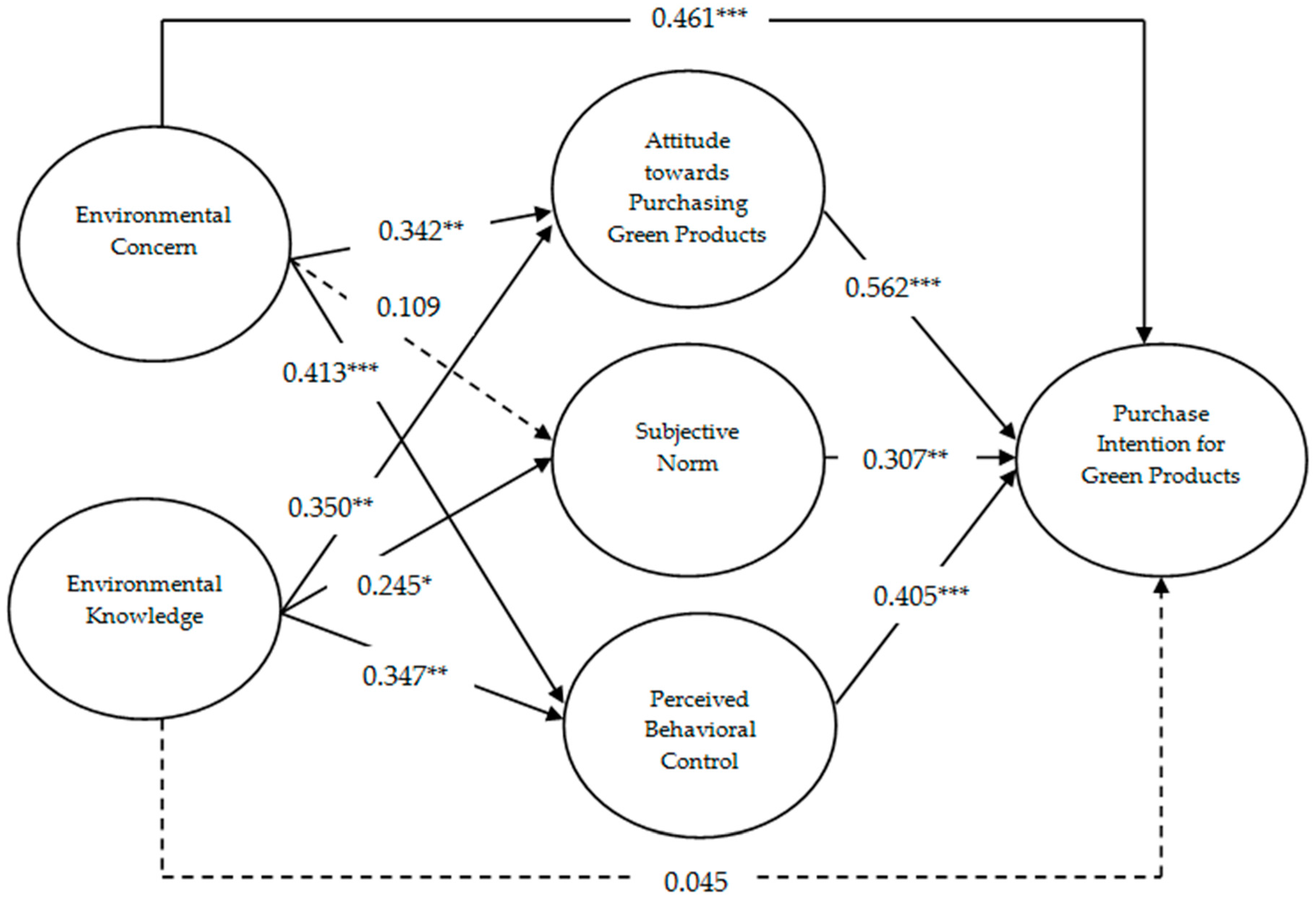

4.2. Testing of the Structural Equation Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bonini, S.M.; Oppenheim, J.M. Cultivating the green consumer. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2008, 6, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.; Modi, A.; Patel, J. Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeiteiro, U.M.; Alves, F.; Pinto de Moura, A.; Pardal, M.Â.; Pita, C.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Pierce, G.J. Participatory issues in fisheries governance in europe. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 23, 347–361. [Google Scholar]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O. Corporate social responsibility and marketing: An integrative framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kärnä, J.; Hansen, E.; Juslin, H. Social responsibility in environmental marketing planning. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 848–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B.; Iyer, E.S.; Kashyap, R.K. Corporate environmentalism: Antecedents and influence of industry type. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Pathak, G.S. Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haytko, D.L.; Matulich, E. Green advertising and environmentally responsible consumer behaviors: Linkages examined. J. Manag. Mark. Res. 2008, 1, 2–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, Á.M.; Borchardt, M.; Vaccaro, G.L.; Pereira, G.M.; Almeida, F. Motivations for promoting the consumption of green products in an emerging country: Exploring attitudes of brazilian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont, O.; Plepys, A. Sustainable consumption progress: Should we be proud or alarmed? J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijuan, L. Enhancing sustainable development through developing green food: China’s option. In Sub-Regional Workshop; Dfid Ii Project, Ed.; United Nations in Bangkok: BKK, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Calkins, M. Materials for Sustainable Sites: A Complete Guide to the Evaluation, Selection, and Use of Sustainable Construction Materials; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J. Sometimes consumers will pay more to go green. Mark. News 1992, 26, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, R.Y.K.; Lau, L.B.Y. Explaining green purchasing behavior: A cross-cultural study on american and chinese consumers. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2002, 14, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, N.A.; Bishop, M.; Gruen, T. Who pays more (or less) for pro-environmental consumer goods? Using the auction method to assess actual willingness-to-pay. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthes, J.; Wonneberger, A.; Schmuck, D. Consumers’ green involvement and the persuasive effects of emotional versus functional ads. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwezen, M.C.; Bartels, J.; Antonides, G. Environmentally friendly consumer choices: Cultural differences in the self-regulatory function of anticipated pride and guilt. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanchanapibul, M.; Lacka, E.; Wang, X.; Chan, H.K. An empirical investigation of green purchase behaviour among the young generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 66, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; de Magistris, T. Organic food product purchase behaviour: A pilot study for urban consumers in the south of italy. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 5, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.-H.; Gao, Q.; Wu, Y.-P.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.-D. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green products: An exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the east. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B. Theory of Planned Behaviour Approach to Understand the Purchasing Behaviour for Environmentally Sustainable Products; Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Research and Publication Department: Ahmedabad, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chairy, C. Spirituality, self-transcendence, and green purchase intention in college students. J. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 57, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.-C. The roles of knowledge, threat, and pce on green purchase behaviour. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 6, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuttavuthisit, K.; Thøgersen, J. The importance of consumer trust for the emergence of a market for green products: The case of organic food. J. Bus. Ethics 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongmahadlek, J. An empirical study on organic product purchasing behavior: A case study of thailand. AU J. Manag. 2012, 10, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Arttachariya, P. Environmentalism and green purchasing behavior: A study on graduate students in Bangkok, Thailand. BU Acad. Rev. 2012, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Manstead, A.S. Changing health-related behaviors: An approach based on the theory of planned behavior. In The Scope of Social Psychology: Theory and Applications; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Vazifehdoust, H.; Taleghani, M.; Esmaeilpour, F.; Nazari, K.; Khadang, M. Purchasing green to become greener: Factors influence consumers’ green purchasing behavior. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2013, 3, 2489–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakersalehi, M.; Zakersalehi, A. Consumers’ attitude and purchasing intention toward green packaged foods: A malaysian perspective. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on Economics, Marketing and Management, Hong Kong, China, 5–7 January 2012; Volume 28, pp. 1–5.

- Gilg, A.; Barr, S.; Ford, N. Green consumption or sustainable lifestyles? Identifying the sustainable consumer. Futures 2005, 37, 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 888–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, R.H. Environmental attitudes and the prediction of behavior. In Environmental Psychology: Directions and Perspectives; Feimer, N.R., Geller, E.S., Eds.; Praeger: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 257–287. [Google Scholar]

- Ohtomo, S.; Hirose, Y. The dual-process of reactive and intentional decision-making involved in eco-friendly behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.; Vigar-Ellis, D. Consumer understanding, perceptions and behaviours with regard to environmentally friendly packaging in a developing nation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Zamora, M.; Parras-Rosa, M.; Murgado-Armenteros, E.M.; Torres-Ruiz, F.J. A powerful word: The influence of the term ‘organic’ on perceptions and beliefs concerning food. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, T.; Yilmaz, V.; Aksoy, H. Structural equation model for environmentally conscious purchasing behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2012, 6, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen, A.; Meyer, R. Environmental attitudes in cross-national perspective: A multilevel analysis of the issp 1993 and 2000. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 26, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidique, S.F.; Lupi, F.; Joshi, S.V. The effects of behavior and attitudes on drop-off recycling activities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- National Statistics Office (NSO). The 2015 Household Socio-Economic Survey Whole Kingdom; NSO: Bangkok, Thailand, 2016.

- Teerachote, C.; Kessomboom, P.; Rattanasiri, A.; Koju, R. Improving health consciousness and life skills in young people through peer-leadership in thailand. Kathmandu Univ. Med. J. 2014, 11, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.K. Green supply-chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soonthonsmai, V. Environmental or Green Marketing as Global Competitive Edge: Concept, Synthesis, and Implication. In Proceedings of the EABR (Business) and ETLC (Teaching) Conference, Venice, Italy, 4–7 June 2007.

- Azeiteiro, U.M.; Alves, F.; Pinto de Moura, A.; Pardal, M.Â.; Pinto de Moura, A.; Cunha, L.M.; Castro-Cunha, M.; Costa Lima, R. A comparative evaluation of women’s perceptions and importance of sustainability in fish consumption: An exploratory study among light consumers with different education levels. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2012, 23, 451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, T.; Bostan, I.; Manolică, A.; Mitrica, I. Profile of green consumers in romania in light of sustainability challenges and opportunities. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6394–6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Peng, N. Green hotel knowledge and tourists’ staying behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 2211–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klopping, I.M.; McKinney, E. Extending the technology acceptance model and the task-technology fit model to consumer e-commerce. Inform. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2004, 22, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T.J. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; McDonald, R.; Louis, W.R. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.E.; Carey, K.B. The theory of planned behavior as a model of heavy episodic drinking among college students. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007, 21, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patch, C.S.; Tapsell, L.C.; Williams, P.G. Attitudes and intentions toward purchasing novel foods enriched with omega-3 fatty acids. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2005, 37, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liobikienė, G.; Mandravickaitė, J.; Bernatonienė, J. Theory of planned behavior approach to understand the green purchasing behavior in the EU: A cross-cultural study. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 125, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai, G.; Teng, P.K.; Mohamed, Z.; Shamsudin, M.N. Consumers’ awareness and consumption intention towards green foods. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 4496–4503. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D.; Hillier, D. Sustainability in the global shop window. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2011, 39, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, P. A perspective on environmental sustainability. In Paper on the Victorian Commissioner for Environmental Sustainability; RSTI Publications, Inc.: Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 2004; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, R.H. Attitudes as object-evaluation associations: Determinants, consequences, and correlates of attitude accessibility. Attitude Strength Anteced. Conseq. 1995, 4, 247–282. [Google Scholar]

- Bonne, K.; Vermeir, I.; Bergeaud-Blackler, F.; Verbeke, W. Determinants of halal meat consumption in france. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Kanuk, L.L. Purchasing Behavior; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. Attitude strength, attitude structure, and resistance to change. Attitude Strength Anteced. Conseq. 1995, 4, 413–432. [Google Scholar]

- Irland, L.C. Wood producers face green marketing era: Environmentally sound products. Wood Technol. 1993, 120, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tsen, C.-H.; Phang, G.; Hasan, H.; Buncha, M.R. Going green: A study of consumers’ willingness to pay for green products in kota kinabalu. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2006, 7, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, M.M. A hierarchical analysis of the green consciousness of the egyptian consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 445–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Theories of cognitive self-regulation the theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hee, S. Relationships among attitudes and subjective norm: Testing the theory of reasoned action cultures. Commun. Stud. 2000, 51, 162–175. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S.; Maguire, J.S. Consumers and consumption. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 30, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiriyapinit, M. Is thai culture the right culture for knowledge management?: An exploratory case study research. Chulalongkorn Rev. 2007, 74, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Dean, M.; Raats, M.M.; Shepherd, R. The role of self-identity, past behavior, and their interaction in predicting intention to purchase fresh and processed organic food. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 669–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.-M.; Wu, K.-S.; Liu, H.-H. Integrating altruism and the theory of planned behavior to predict patronage intention of a green hotel. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Thøgersen, J.; Ruan, Y.; Huang, G. The moderating role of human values planned behaviour: The case of chinese consumers’ intention to buy organic food. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Daugherty, T.; Biocca, F. Impact of 3-D advertising on product knowledge, brand attitude, and purchase intention: The mediating role of presence. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.O. Antecedents of seafood consumption behavior: An overview. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2004, 13, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.W.; Al-Gahtani, S.S.; Hubona, G.S. The effects of gender and age on new technology implementation in a developing country: Testing the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Inform. Technol. People 2007, 20, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Decomposition and crossover effects in the theory of planned behavior: A study of consumer adoption intentions. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1995, 12, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Consumer decision-making with regard to organic food products: Results from the condor project. In Proceedings of the Traditional Food Processing and Technological Innovation Conference, Faro, Portugal, 26 May 2006.

- Tarkiainen, A.; Sundqvist, S. Subjective norms, attitudes and intentions of finnish consumers in buying organic food. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.K. Thinking green, buying green? Drivers of pro-environmental purchasing behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2015, 32, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibeli, M.A.; Johnson, C. Environmental concern: A cross national analysis. J. Int. Cross-Cult. Stud. 2009, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, A.L.; Harun, A.; Hussein, Z. The influence of environmental knowledge and concern on green purchase intention the role of attitude as a mediating variable. Br. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2012, 7, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, R.K.; Greenhalgh, L. Organic confusion: Sustaining competitive advantage. Br. Food J. 1997, 99, 336–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Titterington, A.J.; Cochrane, C. Who buys organic food? A profile of the purchasers of organic food in northern ireland. Br. Food J. 1995, 97, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Aksoy, S.; Caber, M. The effect of environmental concern and scepticism on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, R.; Darmayanti, D. The influence factors of green purchasing behavior: A study of university students in Jakarta. In Proceedings of the 6th Asian Business Research Conference, Bangkok, Thailand, 8–10 April 2012; pp. 1–11.

- Hanson, C.B. Environmental concern, attitude toward green corporate practices, and green consumer behavior in the United States and Canada. ASBBS E J. 2013, 9, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S. How does environmental concern influence specific environmentally related behaviors? A new answer to an old question. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufique, K.M.R.; Siwar, C.; Chamhuri, N.; Sarah, F.H. Integrating general environmental knowledge and eco-label knowledge in understanding ecologically conscious consumer behavior. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 37, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryxell, G.E.; Lo, C.W. The influence of environmental knowledge and values on managerial behaviours on behalf of the environment: An empirical examination of managers in china. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 46, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.; Lynchehaun, F. Organic milk: Attitudes and consumption patterns. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Choi, Y.J.; Youn, C.; Lee, Y. Does green fashion retailing make consumers more eco-friendly? The influence of green fashion products and campaigns on green consciousness and behavior. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2012, 30, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, N.; Ganapathi, R. Influence of consumer’s socio-economic characteristics and attitude on purchase intention of green products. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 33–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Qi, Y. Factors influencing sustainable consumption behaviors: A survey of the rural residents in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Molina, M.A.; Fernández-Sáinz, A.; Izagirre-Olaizola, J. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. Shades of green: A psychographic segmentation of the green consumer in kuwait using self-organizing maps. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11030–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.C.; Waliczek, T.M.; Zajicek, J.M. Relationship between environmental knowledge and environmental attitude of high school students. J. Environ. Educ. 2010, 30, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Diehl, K.; Brinberg, D.; Kidwell, B. Subjective knowledge, search locations, and consumer choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.J.; Kahlor, L. What, me worry? The role of affect in information seeking and avoidance. Sci. Commun. 2013, 35, 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Yun, S.; Lee, J. Can companies induce sustainable consumption? The impact of knowledge and social embeddedness on airline sustainability programs in the us. Sustainability 2014, 6, 3338–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y. Determinants of Chinese consumers’ green purchase behavior. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, T. The impact of values, environmental concern, and willingness to accept economic sacrifices to protect the environment on tourists’ intentions to buy ecologically sustainable tourism alternatives. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 11, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An investigation of green hotel customers’ decision formation: Developing an extended model of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwitt, L.F.; Pitts, R.E. Predicting purchase intentions for an environmentally sensitive product. J. Consum. Psychol. 1996, 5, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szolnoki, G.; Hoffmann, D. Online, face-to-face and telephone surveys—Comparing different sampling methods in wine consumer research. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnear, T.; Taylor, J. Marketing Research: An Applied Research; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I. Elements of statistical description and estimation. In Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; Nunnally, J.C., Bernstein, I.H., Eds.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Charter, M. Greener Marketing: A Global Perspective on Greening Marketing Practice; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, M.M. Antecedents of Egyptian consumers’ green purchase intentions: A hierarchical multivariate regression model. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2006, 19, 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Chen, S.W. The impact of online store environment cues on purchase intention: Trust and perceived risk as a mediator. Online Inform. Rev. 2008, 32, 818–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Questionnaire design and scale development. In The Handbook of Marketing Research: Uses, Misuses, and Future Advances; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 176–202. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-Y.; Weng, C.-S. The influence of environmental friendliness on green trust: The mediation effects of green satisfaction and green perceived quality. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10135–10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.-L. Evaluating green hotels in taiwan from the consumer’s perspective. Int. J. Manag. Res. Bus. Strategy 2015, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.; Black, W. Conjoint analysis. In Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 387–441. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.H. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S.; Osterlind, S.J. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 97, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoe, S.L. Issues and procedures in adopting structural equation modeling technique. J. Appl. Quant. Methods 2008, 3, 76–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol. Methods Res. 1989, 17, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Kast, S.W. Promoting sustainable consumption: Determinants of green purchases by swiss consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H. Negative word-of-mouth communication intention: An application of the theory of planned behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Thyagaraj, K. Consumer’s intention to purchase green brands: The roles of environmental concern, environmental knowledge and self expressive benefits. Curr. World Environ. 2015, 10, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B. Consumer values and green products consumption in malaysia: A structural equation modelling approach. In Handbook of Research on Consumerism and Buying Behavior in Developing Nations; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 383–408. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Items | Classification | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 198 | 40.99 |

| Female | 285 | 59.01 | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 79 | 16.36 |

| 25–34 years | 203 | 42.03 | |

| 35–44 years | 132 | 27.33 | |

| 45–54 years | 46 | 9.52 | |

| 55–64 years | 19 | 3.93 | |

| 65 years or older | 4 | 0.83 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 187 | 38.72 |

| Married | 282 | 58.39 | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 14 | 2.90 | |

| Education | High school | 47 | 9.73 |

| Diploma | 68 | 14.08 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 213 | 44.10 | |

| Master’s degree | 134 | 27.74 | |

| Doctoral degree | 21 | 4.35 | |

| Family size | 1 person | 15 | 3.11 |

| 2–3 persons | 281 | 58.18 | |

| 4–5 persons | 165 | 34.16 | |

| More than 5 persons | 22 | 4.55 | |

| Employment status | Student | 59 | 12.22 |

| Housewife | 81 | 16.77 | |

| Unemployed | 47 | 9.73 | |

| Business | 120 | 24.84 | |

| Full-time job | 158 | 32.71 | |

| Part-time job | 18 | 3.73 | |

| Personal income—monthly (THB) | Less than 10,000 | 43 | 8.90 |

| 10,001–20,000 | 66 | 13.66 | |

| 20,001–30,000 | 135 | 27.95 | |

| 30,001–40,000 | 169 | 34.99 | |

| 40,001–50,000 | 31 | 6.42 | |

| More than 50,001 | 39 | 8.07 |

| Constructs/Questionnaire Items | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards purchasing green products | 4.102 | 0.847 |

| ATT1: I think that purchasing green product is favorable | 4.081 | 0.728 |

| ATT2: I think that purchasing green product is a good idea | 4.264 | 0.771 |

| ATT3: I think that purchasing green product is safe | 3.962 | 0.638 |

| Subjective norm | 3.424 | 0.991 |

| SN1: My family think that I should purchase green products rather than normal products | 3.372 | 0.943 |

| SN2: My close friends think that I should purchase green products rather than normal products | 3.468 | 0.991 |

| SN3: Most people who are important to me think I should purchase green products rather than normal products | 3.433 | 0.978 |

| Perceived behavioral control | 4.004 | 0.843 |

| PBC1: I am confident that I can purchase green products rather than normal products when I want | 3.560 | 0.974 |

| PBC2: I see myself as capable of purchasing green products in future | 4.218 | 0.742 |

| PBC3: I have resources, time and willingness to purchase green products | 4.342 | 0.737 |

| PBC4: There are likely to be plenty of opportunities for me to purchase green products | 3.894 | 0.851 |

| Environmental concern | 4.125 | 0.773 |

| EC1: I am very concerned about the state of the world’s environment | 4.314 | 0.731 |

| EC2: I am willing to reduce my consumption to help protect the environment | 4.481 | 0.876 |

| EC3: Major social changes are necessary to protect the natural environment | 3.860 | 0.832 |

| EC4: Major political change is necessary to protect the natural environment | 3.843 | 0.893 |

| Environmental knowledge | 3.789 | 0.835 |

| EK1: I prefer to check the eco-labels and certifications on green products before purchase | 3.874 | 0.814 |

| EK2: I want to have a deeper insight of the inputs, processes and impacts of products before purchase | 3.935 | 0.762 |

| EK3: I would prefer to gain substantial information on green products before purchase | 3.557 | 0.978 |

| Purchase intention for green products | 4.130 | 0.764 |

| PI1: I intend to purchase green products next time because of its positive environmental contribution | 3.893 | 0.852 |

| PI2: I plan to purchase more green products rather than normal products | 4.097 | 0.813 |

| PI3: I will consider switching to eco-friendly brands for ecological reasons | 4.399 | 0.781 |

| Construct | Question Item | Cronbach’s α | Standardized Factor Loading | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards purchasing green products (ATT) | ATT1 | 0.858 | 0.891 a | 0.873 | 0.680 |

| ATT2 | 0.720 *** | ||||

| ATT3 | 0.854 *** | ||||

| Subjective norm (SN) | SN1 | 0.808 | 0.705 a | 0.812 | 0.593 |

| SN2 | 0.760 *** | ||||

| SN3 | 0.834 *** | ||||

| Perceived behavioral control (PBC) | PBC1 | 0.850 | 0.704 a | 0.852 | 0.591 |

| PBC2 | 0.768 *** | ||||

| PBC3 | 0.830 *** | ||||

| PBC4 | 0.813 *** | ||||

| Environmental concern (EC) | EC1 | 0.892 | 0.826 a | 0.893 | 0.735 |

| EC2 | 0.860 *** | ||||

| EC3 | 0.885 *** | ||||

| EC4 | 0.856 *** | ||||

| Environmental knowledge (EK) | EK1 | 0.830 | 0.745 a | 0.830 | 0.624 |

| EK2 | 0.794 *** | ||||

| EK3 | 0.823 *** | ||||

| Purchase intention for green products (PI) | PI1 | 0.943 | 0.854 a | 0.946 | 0.856 |

| PI2 | 0.950 *** | ||||

| PI3 | 0.970 *** |

| Fit Indices | Criteria | Indicators | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | p > 0.050 | 261.507 (p < 0.001) | [123,124,125,126] |

| Chi-square/df (degree of freedom) | <5.000 | 3.845 (261.507/68) | |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | >0.900 | 0.939 | |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | >0.900 | 0.918 | |

| Relative Fit Index (RFI) | >0.900 | 0.969 | |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | >0.900 | 0.963 | |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | >0.950 | 0.971 | |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | <0.080 | 0.068 | |

| Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) | <0.050 | 0.039 |

| ATT1 | ATT2 | ATT3 | SN1 | SN2 | SN3 | PBC1 | PBC2 | PBC3 | PBC4 | EC1 | EC2 | EC3 | EC4 | EK1 | EK2 | EK3 | PI1 | PI2 | PI3 | |

| ATT1 | 1.000 | 0.509 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.448 *** | 0.405 *** | 0.479 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.443 *** | 0.539 *** | 0.474 *** | 0.446 *** | 0.453 *** | 0.473 *** | 0.475 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.527 *** | 0.443 *** | 0.489 *** | 0.559 *** |

| ATT2 | 1.000 | 0.613 *** | 0.535 *** | 0.523 *** | 0.497 *** | 0.451 *** | 0.522 *** | 0.508 *** | 0.486 *** | 0.463 *** | 0.490 *** | 0.507 *** | 0.487 *** | 0.544 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.465 *** | 0.442 *** | 0.447 *** | |

| ATT3 | 1.000 | 0.713 *** | 0.407 *** | 0.452 *** | 0.305 *** | 0.285 *** | 0.416 *** | 0.530 *** | 0.460 *** | 0.530 *** | 0.410 *** | 0.592 *** | 0.502 *** | 0.396 *** | 0.502 *** | 0.342 *** | 0.507 *** | 0.581 *** | ||

| SN1 | 1.000 | 0.454 *** | 0.458 *** | 0.573 *** | 0.385 *** | 0.590 *** | 0.579 *** | 0.448 *** | 0.452 *** | 0.395 *** | 0.381 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.327 *** | 0.435 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.402 *** | |||

| SN2 | 1.000 | 0.452 *** | 0.592 *** | 0.610 *** | 0.566 *** | 0.477 *** | 0.440 *** | 0.409 *** | 0.412 *** | 0.417 *** | 0.554 *** | 0.640 *** | 0.456 *** | 0.464 *** | 0.561 *** | 0.467 *** | ||||

| SN3 | 1.000 | 0.751 *** | 0.435 *** | 0.529 *** | 0.584 *** | 0.428 *** | 0.496 *** | 0.508 *** | 0.455 *** | 0.464 *** | 0.370 *** | 0.444 *** | 0.537 *** | 0.579 *** | 0.465 *** | |||||

| PBC1 | 1.000 | 0.714 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.510 *** | 0.413 *** | 0.370 *** | 0.427 *** | 0.359 *** | 0.481 *** | 0.484 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.395 *** | 0.489 *** | 0.548 *** | ||||||

| PBC2 | 1.000 | 0.605 *** | 0.511 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.302 *** | 0.428 *** | 0.428 *** | 0.473 *** | 0.510 *** | 0.311 *** | 0.431 *** | 0.581 *** | 0.441 *** | |||||||

| PBC3 | 1.000 | 0.608 *** | 0.550 *** | 0.449 *** | 0.597 *** | 0.404 *** | 0.441 *** | 0.343 *** | 0.437 *** | 0.486 *** | 0.531 *** | 0.480 *** | ||||||||

| PBC4 | 1.000 | 0.405 *** | 0.511 *** | 0.484 *** | 0.499 *** | 0.377 *** | 0.369 *** | 0.596 *** | 0.504 *** | 0.559 *** | 0.430 *** | |||||||||

| EC1 | 1.000 | 0.692 *** | 0.755 *** | 0.544 *** | 0.512 *** | 0.477 *** | 0.499 *** | 0.500 *** | 0.513 *** | 0.585 *** | ||||||||||

| EC2 | 1.000 | 0.601 *** | 0.548 *** | 0.483 *** | 0.375 *** | 0.523 *** | 0.517 *** | 0.372 *** | 0.536 *** | |||||||||||

| EC3 | 1.000 | 0.524 *** | 0.581 *** | 0.465 *** | 0.515 *** | 0.487 *** | 0.482 *** | 0.495 *** | ||||||||||||

| EC4 | 1.000 | 0.503 *** | 0.351 *** | 0.463 *** | 0.475 *** | 0.536 *** | 0.452 *** | |||||||||||||

| EK1 | 1.000 | 0.523 *** | 0.431 *** | 0.362 *** | 0.524 *** | 0.469 *** | ||||||||||||||

| EK2 | 1.000 | 0.538 *** | 0.392 *** | 0.532 *** | 0.406 *** | |||||||||||||||

| EK3 | 1.000 | 0.537 *** | 0.496 *** | 0.520 *** | ||||||||||||||||

| PI1 | 1.000 | 0.769 *** | 0.530 *** | |||||||||||||||||

| PI2 | 1.000 | 0.712 *** | ||||||||||||||||||

| PI3 | 1.000 |

| Fit Indices | Criteria | Indicators | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chi-square | p > 0.050 | 320.991 (p < 0.001) | [124,125,126] |

| Chi-square/df (degree of freedom) | <5.000 | 4.521 (320.991/71) | |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | >0.900 | 0.949 | |

| Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) | >0.900 | 0.926 | |

| Relative Fit Index (RFI) | >0.900 | 0.978 | |

| Normed Fit Index (NFI) | >0.900 | 0.976 | |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | >0.950 | 0.958 | |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | <0.080 | 0.065 | |

| Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) | <0.050 | 0.027 |

| Hypothesis | Path Correlation | Standardized Path Coefficient | t-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Attitude towards purchasing green products → Purchase intention for green products | 0.562 *** | 8.512 | Supported |

| H2 | Subjective norm → Purchase intention for green products | 0.307 ** | 5.012 | Supported |

| H3 | Perceived behavioral control → Purchase intention for green products | 0.405 *** | 6.512 | Supported |

| H4 | Environmental concern → Purchase intention for green products | 0.461 *** | 6.770 | Supported |

| H5 | Environmental concern → Attitude towards purchasing green products | 0.342 ** | 6.322 | Supported |

| H6 | Environmental concern → Subjective norm | 0.109 | 1.498 | Not supported |

| H7 | Environmental concern → Perceived behavioral control | 0.413 *** | 8.921 | Supported |

| H8 | Environmental knowledge → Purchase intention for green products | 0.045 | 0.827 | Not supported |

| H9 | Environmental knowledge → Attitude towards purchasing green products | 0.350 ** | 4.977 | Supported |

| H10 | Environmental knowledge → Subjective norm | 0.245 * | 3.478 | Supported |

| H11 | Environmental knowledge → Perceived behavioral control | 0.347 ** | 6.458 | Supported |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maichum, K.; Parichatnon, S.; Peng, K.-C. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Investigate Purchase Intention of Green Products among Thai Consumers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101077

Maichum K, Parichatnon S, Peng K-C. Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Investigate Purchase Intention of Green Products among Thai Consumers. Sustainability. 2016; 8(10):1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101077

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaichum, Kamonthip, Surakiat Parichatnon, and Ke-Chung Peng. 2016. "Application of the Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Investigate Purchase Intention of Green Products among Thai Consumers" Sustainability 8, no. 10: 1077. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8101077