Wellness Tourism among Seniors in Taiwan: Previous Experience, Service Encounter Expectations, Organizational Characteristics, Employee Characteristics, and Customer Satisfaction

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wellness Tourism and Spas

2.2. Service Encounter Expectations

2.3. Previous Experience

2.4. Organizational Attributes of Spa Hotels

2.5. Customer Satisfaction

3. Methodology

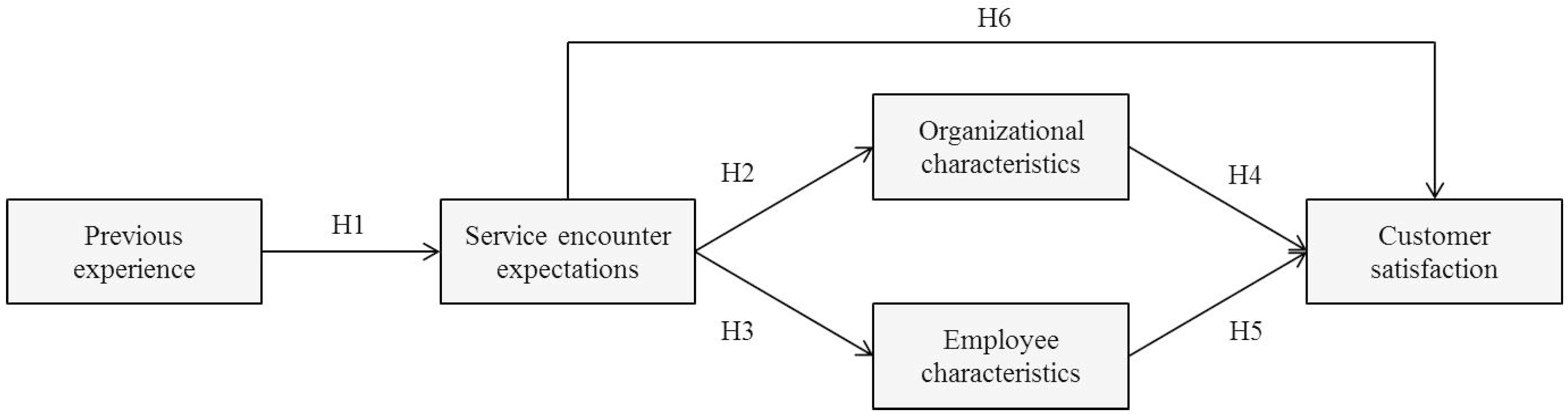

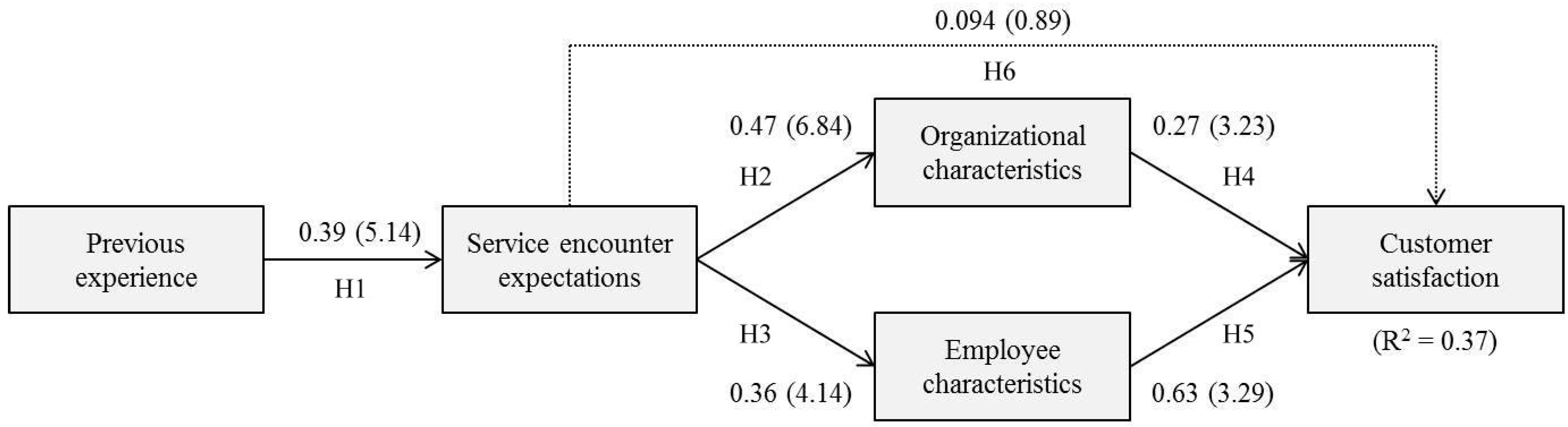

3.1. Research Framework and Hypotheses

| Codes | Research hypotheses |

|---|---|

| H1 | Previous experience has a significant and positive influence on service encounter expectations. |

| H2 | Service encounter expectations have a significant and positive influence on organizational characteristics. |

| H3 | Service encounter expectations have a significant and positive influence on employee characteristics. |

| H4 | Organizational characteristics have a significant and positive influence on customer satisfaction. |

| H5 | Employee characteristics have a significant and positive influence on customer satisfaction. |

| H6 | Service encounter expectations have a significant and positive influence on customer satisfaction. |

3.2. Questionnaire Design

| Variables | Operational definition | Number of items | Measurement scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous experience | The awareness of the service experiences of being a customer or an employee among older adults | 4 | 5-point Likert scale |

| Service encounter expectations | In the interactive relationship between service providers and service receivers, customers’ awareness of all the things that they expect to obtain from service providers or the services that they consider should be provided | 31 | 5-point Likert scale |

| Organizational characteristics | The awareness of older adults regarding the organizational size, location, personnel policies, and marketing techniques of a hotel | 16 | 5-point Likert scale |

| Employee characteristics | The awareness of older adults regarding the ages and attitudes of employees | 8 | 5-point Likert scale |

| Customer satisfaction | The differences between customer expectations and the service performance of businesses | 24 | 5-point Likert scale |

3.3. Common Method Variance Test for Respondents and Data Acquisition

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2. Item Analysis of Previous Experience, Organizational Characteristics, and Employee Characteristics

| Variables | Data category | Number of samples | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 134 | 38.7 |

| Female | 210 | 60.7 | |

| Age | 50–64 years old | 222 | 64.2 |

| 65 years old and above | 120 | 34.7 | |

| Marital status | Married | 322 | 93.1 |

| Single | 8 | 2.30 | |

| Other | 10 | 2.90 | |

| Educational attainment | Junior high school and below | 76 | 22.0 |

| Senior (vocational) high school | 110 | 31.8 | |

| College/university | 126 | 36.4 | |

| Graduate school and above | 26 | 7.50 | |

| Current occupation or industry | Retired | 176 | 50.9 |

| Military, public, and teaching personnel | 18 | 5.20 | |

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing, and animal husbandry | 6 | 1.70 | |

| Service sector | 32 | 9.20 | |

| Industrial sector | 5 | 1.40 | |

| Self-employed | 29 | 8.40 | |

| Housewife | 59 | 17.1 | |

| Commerce | 10 | 2.90 | |

| Technology industry | 3 | 0.90 | |

| Other | 8 | 2.30 | |

| Major residence | Northern Taiwan | 206 | 59.5 |

| Central Taiwan | 30 | 8.70 | |

| Southern Taiwan | 101 | 29.2 | |

| Eastern Taiwan | 3 | 0.90 | |

| Monthly disposable income (NT$) | 20 thousand and below | 93 | 26.9 |

| 20–40 thousand | 101 | 29.2 | |

| 40–60 thousand | 68 | 19.7 | |

| 60–80 thousand | 33 | 9.50 | |

| 80–100 thousand | 14 | 4.00 | |

| 100 thousand and above | 17 | 4.90 | |

| Self-perceived health condition | Very unhealthy | 9 | 2.60 |

| Unhealthy | 4 | 1.20 | |

| Average | 105 | 30.3 | |

| Healthy | 189 | 54.6 | |

| Very healthy | 38 | 11.0 |

| Variables | Item | t value | Item-to-total correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previous experience | I have been here, and when I revisit this place, I expect to experience the same service quality because I felt satisfied in my previous visit(s). | 4.11 | 0.80 |

| According to my previous travel experience, I think that the service of this spa hotel is reliable. | 5.00 | 0.73 | |

| After collecting relevant information, I think that the service provided by this spa hotel is the best choice. | 6.69 | 0.78 | |

| According to my service-related work experience, I think that the service of this spa hotel is reliable. | 6.55 | 0.74 | |

| Organizational characteristics | I think that large service places provide a greater number of services than small service places do. | 7.45 | 0.43 * |

| I think that large service places cost more than small service places do but provide superior services. | 4.19 | 0.26 * | |

| I list service places with a relatively greater size as a priority in choosing service places. | 7.65 | 0.42 * | |

| The transportation to the spa hotel is convenient. | 9.57 | 0.51 | |

| The spa hotel has a beautiful view and environment. | 11.24 | 0.53 | |

| The service staff contains middle-aged reemployed workers. | 9.67 | 0.52 | |

| Members of the service staff have a background in medical care (e.g., nurses or dietitians). | 10.73 | 0.54 | |

| Members of the service staff possess healthcare-related certifications (e.g., physical therapists, fitness instructors for older adults, or nurse aides). | 11.74 | 0.55 | |

| The sensing devices installed at the service location involve door sensors. | 12.53 | 0.63 | |

| The sensing devices installed at the service location include checkout functions. | 10.86 | 0.59 | |

| The sensing devices provided at the service location include electronic meal vouchers. | 10.40 | 0.56 | |

| The sensing devices provided at the service location include spa time reminders. | 11.95 | 0.63 | |

| Service staff members frequently give sincere (nonstandardized) greetings. | 13.17 | 0.63 | |

| Service staff members frequently have sincere (nonstandardized) expressions. | 12.88 | 0.64 | |

| The spa hotel actively reminds me of the time of my next vacation activity. | 10.22 | 0.54 | |

| The spa hotel actively sends me accommodation coupons for special holidays. | 10.77 | 0.58 | |

| Employee characteristics | The service provided by senior service staff members can better satisfy my needs compared with that provided by young service staff members. | 7.26 | 0.74 |

| The service provided by senior service staff members is more satisfactory than that provided by young staff members. | 6.35 | 0.71 | |

| Senior service staff members are more patient in listening to my inquiries than young service staff members are. | 5.36 | 0.65 | |

| Service staff members respect my needs. | 10.69 | 0.68 | |

| During service, service staff members make me feel respected and honored. | 8.08 | 0.67 | |

| Service staff members treat me like they do their own senior relatives. | 8.33 | 0.72 | |

| Service staff members actively approach and serve me. | 7.17 | 0.72 | |

| Service staff members remain dedicated to serving customers during service delivery. | 8.20 | 0.72 |

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis of Previous Experience, Service Encounter Expectations, Organizational Characteristics, and Employee Characteristics

| Factor | Questionnaire item | Factor loading | Mean | Standard deviation | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Previous experience | |||||

| Previous experience (M = 3.713) | I have been here, and when I revisit this place, I expect to experience the same service quality because I felt satisfied in my previous visit(s). | 0.792 | 3.77 | 0.744 | 0.779 |

| According to my previous travel experience, I think that the service of this spa hotel is reliable. | 0.776 | 3.79 | 0.699 | ||

| After collecting relevant information, I think that the service provided by this spa hotel is the best choice. | 0.775 | 3.60 | 0.824 | ||

| According to my service-related work experience, I think that the service of this SPA hotel is reliable. | 0.762 | 3.69 | 0.703 | ||

| Service encounter expectations | |||||

| Experience of local tourism resources (M = 3.54) | Local cultural celebration involvement | 0.746 | 3.60 | 0.823 | 0.943 |

| Provide private attractions | 0.680 | 3.66 | 0.849 | ||

| Provide cultural custom experiences | 0.670 | 3.48 | 0.813 | ||

| Community development | 0.628 | 3.40 | 0.802 | ||

| Atmosphere of relaxed tranquility | 0.543 | 3.88 | 0.806 | ||

| Provide nocturnal exploration activities | 0.519 | 3.24 | 0.884 | ||

| Health-improving measures (M = 3.37) | Provide hot spring therapy guidance | 0.787 | 3.40 | 0.897 | |

| Provide medication consultation | 0.785 | 3.26 | 0.916 | ||

| Provide traditional healing | 0.760 | 3.33 | 0.846 | ||

| Provide aquatic workout guidance | 0.631 | 3.39 | 0.905 | ||

| Provide fitness exercise guidance | 0.615 | 3.46 | 0.926 | ||

| Provide weight control guidance | 0.549 | 3.40 | 0.927 | ||

| Spiritual feast (M=3.05) | Provide psychological consultation | 0.776 | 3.01 | 0.962 | |

| Provide enlightenment lectures by resident religious and spiritual mentors | 0.720 | 2.90 | 0.983 | ||

| Provide butler care service | 0.696 | 3.06 | 0.908 | ||

| Provide book clubs | 0.606 | 3.21 | 0.888 | ||

| Body treatments (M = 3.36) | Provide massage | 0.795 | 3.49 | 0.907 | |

| Provide herbal bath | 0.705 | 3.49 | 0.880 | ||

| Provide essence oil massages | 0.703 | 3.26 | 0.884 | ||

| Provide post-surgery recovery care | 0.669 | 3.41 | 0.846 | ||

| Provide exfoliation services | 0.664 | 3.13 | 0.892 | ||

| Enjoying food and relaxation (M = 3.58) | Use of non-toxic or detoxification food ingredients | 0.655 | 3.74 | 0.910 | |

| Provide family activities | 0.617 | 3.67 | 0.871 | ||

| Provide meditation environment | 0.609 | 3.35 | 0.869 | ||

| Provide recreation rooms for chatting and chess | 0.569 | 3.37 | 0.850 | ||

| Provide landscape therapy (environment and psychological consultation) | 0.541 | 3.44 | 0.895 | ||

| Provide local ingredients based cuisines | 0.526 | 3.92 | 0.780 | ||

| Service encounter expectations | |||||

| Mental learning (M = 3.48) | Provide musical performances | 0.684 | 3.58 | 0.890 | 0.943 |

| Provide art exhibitions | 0.622 | 3.42 | 0.901 | ||

| Provide group DIY activities | 0.568 | 3.44 | 0.887 | ||

| Total explained variance = 64.68% | |||||

| Organizational characteristics | |||||

| Marketing techniques (M = 4.13) | Service staff members frequently have sincere (nonstandardized) expressions. | 0.808 | 4.20 | 0.717 | 0.871 |

| Service staff members frequently give sincere (nonstandardized) greetings. | 0.792 | 4.10 | 0.718 | ||

| The spa hotel actively sends me accommodation coupons for special holidays. | 0.575 | 4.25 | 0.746 | ||

| The spa hotel actively reminds me of the time of my next vacation activity. | 0.541 | 3.96 | 0.776 | ||

| Technology services (M = 3.79) | The sensing devices provided at the service location include electronic meal vouchers. | 0.842 | 3.65 | 0.753 | |

| The sensing devices installed at the service location include checkout functions. | 0.758 | 3.71 | 0.782 | ||

| The sensing devices provided at the service location include spa time reminders. | 0.629 | 3.94 | 0.772 | ||

| The sensing devices installed at the service location involve door sensors. | 0.589 | 3.85 | 0.800 | ||

| Basic features (M = 4.04) | The spa hotel has a beautiful view and environment. | 0.784 | 4.21 | 0.669 | |

| The transportation to the spa hotel is convenient. | 0.757 | 4.06 | 0.720 | ||

| The service staff contains middle-aged reemployed workers. | 0.553 | 3.85 | 0.754 | ||

| Professional care (M = 4.06) | Members of the service staff possess health care-related certifications (e.g., physical therapists, fitness instructors for older adults, or nurse aides). | 0.827 | 4.13 | 0.766 | |

| Members of the service staff have a background in medical care (e.g., nurses or dietitians). | 0.674 | 4.10 | 0.721 | ||

| The sensing devices installed at the service location involve door sensors. | 0.581 | 3.96 | 0.745 | ||

| Total explained variance = 66.10% | |||||

| Employee characteristics | |||||

| Employee attitude (M = 4.19) | Service staff members remain dedicated to serving customers during service delivery. | 0.835 | 4.25 | 0.660 | 0.854 |

| During service, service staff members make me feel respected and honored. | 0.823 | 4.21 | 0.654 | ||

| Service staff members treat me like they do their own senior relatives. | 0.823 | 4.18 | 0.727 | ||

| Service staff members respect my needs. | 0.761 | 4.21 | 0.626 | ||

| Service staff members actively approach and serve me. | 0.747 | 4.09 | 0.725 | ||

| Senior employees (M = 3.66) | The service provided by senior service staff members can better satisfy my needs compared with that provided by young service staff members. | 0.893 | 3.61 | 0.846 | |

| Senior service staff members are more patient in listening to my inquiries than young members are. | 0.869 | 3.70 | 0.834 | ||

| The service provided by senior service staff members is more satisfactory than that provided by young staff members. | 0.852 | 3.68 | 0.797 | ||

| Total explained variance = 71.45% | |||||

4.4. Older Adults’ Cognition of New Technology Services

| Automated systems | Group 1 (n = 115) | Group 2 (n = 222) | p value | Post-hoc test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The sensing devices installed at the service location involve door sensors. | 3.37 | 4.26 | 0.00 | 2 > 1 |

| The sensing devices installed at the service location include checkout functions. | 3.06 | 4.05 | 0.00 | 2 > 1 |

| The sensing devices provided at the service location include electronic meal vouchers. | 2.97 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 2 > 1 |

| The sensing devices provided at the service location include spa time reminders. | 3.28 | 4.29 | 0.00 | 2 > 1 |

| Self-perceived health condition | Group 1 | Group 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | ||

| Very unhealthy | 1 (0.90) | 2 (0.90) | |

| Unhealthy | 3 (2.60) | 1 (0.50) | |

| Average | 42 (36.5) | 58 (26.2) | |

| Healthy | 61 (53.0) | 130 (58.6) | |

| Very healthy | 8 (7.00) | 30 (13.6) |

4.5. Differences of Service Encounter Expectations and Customer Satisfaction on Age

| Items | Mean | t value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-older adults | Older adults | |||

| Local cultural celebration involvement | 3.72 | 3.40 | 3.37 | 0.01 * |

| Provide private attractions | 3.77 | 3.44 | 3.47 | 0.01 * |

| Provide cultural custom experiences | 3.55 | 3.36 | 2.05 | 0.04 * |

| Atmosphere of relaxed tranquility | 3.96 | 3.74 | 2.40 | 0.02 * |

| Provide nocturnal exploration activities | 3.31 | 3.08 | 2.37 | 0.02 * |

| Use of non-toxic or detoxification food ingredients | 3.81 | 3.58 | 2.25 | 0.03 * |

4.6. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Customer Satisfaction

| Factor | Item | Factor loading | Error variance | Mean | Standard deviation | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangibles (M = 4.07) | The hotel has modern décor and equipment. | 0.54 | 0.27 | 3.94 | 0.735 | 0.66 | 0.98 |

| The hotel has clean and comfortable restaurants, places, and accommodations | 0.56 | 0.2 | 4.13 | 0.700 | |||

| Hotel service staff members are neatly attired. | 0.5 | 0.21 | 4.05 | 0.675 | |||

| The hotel has elegant and green environments. | 0.64 | 0.18 | 4.10 | 0.759 | |||

| The hotel provides convenient parking. | 0.57 | 0.21 | 4.10 | 0.709 | |||

| Hotel signs and notices are clear and precise. | 0.54 | 0.19 | 4.10 | 0.678 | |||

| Reliability (M = 3.96) | Customers can rapidly obtain required services. | 0.69 | 0.15 | 3.97 | 0.785 | 0.66 | 0.89 |

| Service staff members perform excellently on the first attempt. | 0.6 | 0.19 | 3.91 | 0.733 | |||

| Service staff members provide assistance when customers encounter problems. | 0.58 | 0.18 | 4.03 | 0.717 | |||

| Service staff members are capable of providing promised services. | 0.55 | 0.24 | 3.92 | 0.732 | |||

| Responsiveness (M = 3.79) | Service staff members attend to disregarded tasks immediately. | 0.59 | 0.25 | 3.87 | 0.760 | 0.68 | 0.96 |

| Service staff members do not forget my requests because of being busy. | 0.59 | 0.25 | 3.77 | 0.778 | |||

| Service staff members actively provide assistance and care. | 0.62 | 0.16 | 3.84 | 0.745 | |||

| Service staff members respond to and handle my complaints. | 0.63 | 0.21 | 3.76 | 0.765 | |||

| Service staff members provide excellent service without consulting their supervisors. | 0.62 | 0.28 | 3.73 | 0.800 | |||

| Assurance (M = 3.93) | The image and reputation of the hotel is trustworthy. | 0.56 | 0.22 | 3.92 | 0.727 | 0.66 | 0.88 |

| The hotel provides reliable and satisfactory service. | 0.62 | 0.19 | 3.93 | 0.748 | |||

| Service staff members are trustworthy. | 0.61 | 0.13 | 3.90 | 0.703 | |||

| Service staff members remain cordial and polite during service delivery. | 0.54 | 0.17 | 3.97 | 0.676 | |||

| Empathy (M = 3.79) | Service staff members care about my questions. | 0.68 | 0.18 | 3.84 | 0.731 | 0.71 | 0.92 |

| Service staff members prioritize my interests. | 0.76 | 0.14 | 3.72 | 0.771 | |||

| Service staff members understand my particular needs. | 0.75 | 0.14 | 3.70 | 0.774 | |||

| Service staff members provide immediate assistance to my additional questions. | 0.64 | 0.2 | 3.75 | 0.735 | |||

| The business hours of the hotel facilitate customer inquiries. | 0.5 | 0.28 | 3.92 | 0.685 |

4.7. Validation of Theoretical Model

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Council for Economic Planning and Development. Population projection of the republic of china from 2012 to 2060. Available online: http://www.ndc.gov.tw/m1.aspx?sNo=0059740&key=&ex=2&ic=0000153 (assessed on 7 June 2015).

- Hawes, D.K. Travel-related lifestyle profiles of older women. J. Travel Res. 1988, 27, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, M.; Davey, A.; Kleiber, D. Modeling change in older adults’ leisure activities. Leis. Sci. 2006, 28, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, M. Market in motion: Seniors provide hoteliers with golden opportunities. Hotel Motel Manag. 1998, 213, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, S. Segmenting the mature market: 10 years later. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfurt-Cooper, P.; Cooper, M. Health and Wellness Tourism: Spas and Hot Springs; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. Spa introduction. In Understanding the Global Spa Industry: Spa Management; Bodeker, G., Cohen, M., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schegg, R.; Murphy, J.; Leuenberger, R. Five-star treatment? E-mail customer service by international luxury hotels. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2003, 6, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, E.; King, D.; Lee, J.K.; Warkentin, M.; Chung, H.M. Electronic Commerce: A Managerial Perspective; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Grougiou, V.; Pettigrew, S. Senior customers’ service encounter preferences. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvel, M. Competing in hotel services for seniors. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 18, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M. Role interpretation during service encounters: A critical review of modern approaches to service quality management. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschis, G.P. Marketing to older adults: An updated overview of present knowledge and practice. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The american customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, H.; Lanz Kaufmann, E. Wellness tourism: Market analysis of a special health tourism segment and implications for the hotel industry. J. Vacat. Mark. 2001, 7, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrstedt, W. Wellness: A new perspective for leisure centers, health tourism, and spas in Europe on the global health market. In The Tourism and Leisure Industry: Shaping the Future; Weiermair, K., Mathies, C., Eds.; Haworth Hospitality Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 181–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, S. Trends and skills needed in the tourism sector: “Tourism for wellness”. In Trends and Skill Needs in Tourism; Rens, J.V., Stavrou, S., Eds.; European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2005; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Anspaugh, D.J.; Hamrick, M.H.; Rosato, F.D. Wellness: Concepts and Applications, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Higher Education: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspar, C. Gesundheitstourismus im trend. In Jahrbuch der Schweizer Tourismuswirtschaft 1995/96; Institute of Tourismus und Verkehrswirtschaft, Ed.; Institut für Tourismus und Verkehrswirtschaft: St. Gallen, Switzerland, 1996; pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Puczkó, L. Health and Wellness Tourism; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Puczkó, L.; Bachvarov, M. Spa, bath, thermal: What’s behind the labels? J. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2006, 31, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, L.-F.; Lin, L.-H.; Lin, Y.-Y. A service quality measurement architecture for hot spring hotels in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwan Industrial Technology Research Institute. A study on the Investigation, Exploitation and Utilization of Hot-Spring Resources in Taiwan; Water Resources Agency, Ministry of Economic Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 2004.

- Hsieh, Y.-H.; Lin, Y.-T.; Yuan, S.-T. Expectation-based coopetition approach to service experience design. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2013, 34, 64–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Berry, L.L.; Zeithaml, V.A. Understanding customer expectations of service. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1991, 32, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The nature and determinants of customer expectations of service. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1993, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, M.R.; Surprenant, C.; Czepiel, J.A.; Gutman, E.G. A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: The service encounter. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosby, L.A.; Evans, K.R.; Cowles, D. Relationship quality in services selling: An interpersonal influence perspective. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Wu, C.-M.E. Seniors’ travel motivation and the influential factors: An examination of taiwanese seniors. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Tsai, H.-T. The study of senior traveler behavior in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2003, 24, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.T. Managing two future changes in leisure and tourism services. J. Tour. Hosp. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heung, V.C.S.; Kucukusta, D. Wellness tourism in china: Resources, development and marketing. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 15, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-H.; Liu, H.-H.; Chang, F.-H. Essential customer service factors and the segmentation of older visitors within wellness tourism based on hot springs hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, M.J.; Childers, T.L.; Heckler, S.E. Picture-word consistency and the elaborative processing of advertisements. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T. Schema-Triggered Affect: Applications to Social Perception. In Affect and Cognition: 17th Annual Carnegie Mellon Symposium on Cognition; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mandler, G. The Structure of Value: Accounting for Taste. In Affect and Cognition: The Seventeenth Annual Carnegie Symposium on Cognition; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Clow, K.E.; Kurtz, D.L.; Ozment, J.; Ong, B.S. The antecedents of consumer expectations of services: An empirical study across four industries. J. Serv. Mark. 1997, 11, 230–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, P.A.; Javalgi, R.; Dilorenzo-Aiss, J. An empirical assessment of the zeithaml, berry and parasuraman service expectations model. Serv. Ind. J. 1998, 18, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C. Influences upon consumer expectations of services. J. Serv. Mark. 1991, 5, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Attributional thoughts about consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2000, 27, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, K.P.; Poiesz, T.B.; Wilke, H. Motivation, capacity, and opportunity to complain: Towards a comprehensive model of consumer complaint behavior. Adv. Consum. Res. 1997, 24, 464–469. [Google Scholar]

- Barger, P.B.; Grandey, A.A. Service with a smile and encounter satisfaction: Emotional contagion and appraisal mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-Y. Improving importance-performance analysis: The role of the zone of tolerance and competitor performance. The case of taiwan’s hot spring hotels. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Customer, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hempel, D.J. Consumer Satisfaction with the Home Buying Process: Conceptualization and Measurement; Marketing Science Institute: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; pp. 275–299. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Binter, M. Service Marketing; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. J. Mark. 1985, 49, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Gu, C.; Zhen, F. Examining antecedents and consequences of tourist satisfaction: A structural modeling approach. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2009, 14, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, I.A.; Dioko, L.D.A. Understanding the mediated moderating role of customer expectations in the customer satisfaction model: The case of casinos. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; La, S. The moderating role of confidence in expectations and the asymmetric influence of disconfirmation on customer satisfaction. Serv. Ind. J. 2003, 23, 20–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, K.-H.; Chang, F.-H.; Liu, F.-Y. Wellness Tourism among Seniors in Taiwan: Previous Experience, Service Encounter Expectations, Organizational Characteristics, Employee Characteristics, and Customer Satisfaction. Sustainability 2015, 7, 10576-10601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70810576

Chen K-H, Chang F-H, Liu F-Y. Wellness Tourism among Seniors in Taiwan: Previous Experience, Service Encounter Expectations, Organizational Characteristics, Employee Characteristics, and Customer Satisfaction. Sustainability. 2015; 7(8):10576-10601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70810576

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Kaung-Hwa, Feng-Hsiang Chang, and Fang-Yu Liu. 2015. "Wellness Tourism among Seniors in Taiwan: Previous Experience, Service Encounter Expectations, Organizational Characteristics, Employee Characteristics, and Customer Satisfaction" Sustainability 7, no. 8: 10576-10601. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70810576