Evidence and Experience of Open Sustainability Innovation Practices in the Food Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- the growing number of supply chain actors;

- the variety of customers’ demands;

- end-users;

- legislators and higher quality standards requiring the food sector to open up to new sources of innovation in order to continue to be profitable and successful on the market [4].

2. State of the Art

2.1. Food Sector

| Issue | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Rapid adaptation to different scenarios | A rapid adaptation to new scenarios is needed [18] in which the process of coordination and communication between the main actors of the food sector requires the ability to face constantly changing difficulties. Traditionally, the food industry is considered a low-tech industry that is technology supply-dependent. Innovation in food companies is usually seen as a balance between the technology-push and the demand-pull approaches. It is hardly ever radical, and more often has an incremental nature [19]. As Saguy and Sirotinskaya [20] note, the needs in this kind of industry require that the open innovation process has radical openness, providing a foundation built on four pillars: collaboration, transparency, sharing and empowerment. Furthermore, universities develop and dismiss scientific discoveries, knowledge, inventions and technologies through motivated and highly qualified researchers who contribute to the huge success of the industry-university partnership [20]. |

| Innovative problem solving | It is the need to overcome the structural problem that comes from the numerous SMEs in the European food sector [12,21]. To do so, companies need to cooperate and look for possible external support. Food industry has changing processes that simultaneously focus on safety, high quality food and on health and consumer satisfaction [22]. The chain reversal process that puts the consumer at the center of production implies that companies have to find new innovative technological solutions and find new business models [22]. Therefore the latest important changes in the food demand and in the supply chain organization in a more competitive environment have made innovation a fundamental corporate activity extremely relevant to the profitability of the industry. The actors that cooperate in the supply chain cooperation mechanism could be a large company or a small firm. Innovative food companies that want to increase their knowledge may need to associate with other actors of the supply chain as well as with external possible partners such as: universities and research centers or other industries such as biotechnology, preservation, technology and nanotechnology [22]. |

| Attention to consumer needs | Special attention to consumer needs means that enterprises in this sector are willing to reach the consumers and take their needs into consideration. In this way enterprises could develop technologies, management and communication strategies between enterprises and consumers with the aim of building a trusting relationship [23,24]. Through collaboration with customers comes the need to satisfy them. Therefore, their involvement is crucial. Consumer engagement is natural and essential in this type of company; however, consumers have acquired a further role, more expansive and critical—they have become what is known as “co-creators” [20]. The companies include in their collaborative networks of community real and virtual consumers. This allows them the concept of a participatory model of consumers and cooperation on a larger scale, reaching the global market. Consumers share their experiences of food products, and evaluate their attributes (charm, value, acceptance, ideas, feelings, emotions and experiences) and provide feedback. Also, they have a set of tools for creating value, in the role of co-designers, innovators, marketing or branding [25]. More and more often, consumers demand products closely tailored to their specific needs and health interests, meaning the industry is constantly and rapidly increasing. Therefore, in order to better meet the new and differentiated consumer tendencies, companies have developed more complex marketing techniques. These new challenging tendencies have also compelled the food companies to develop different types of products and to find more technologically innovative solutions and newer business models [22]. |

2.2. Sustainability in the Food Sector

| Sustainability Issues | Requirements |

|---|---|

| Socio-economic | The governance of the food sector needs to be constantly updated. |

| Production | The food production needs to be implemented by using more sustainable, technological and efficient systems. |

| Consumption | Changes in daily diet are needed based on how they can influence food production. |

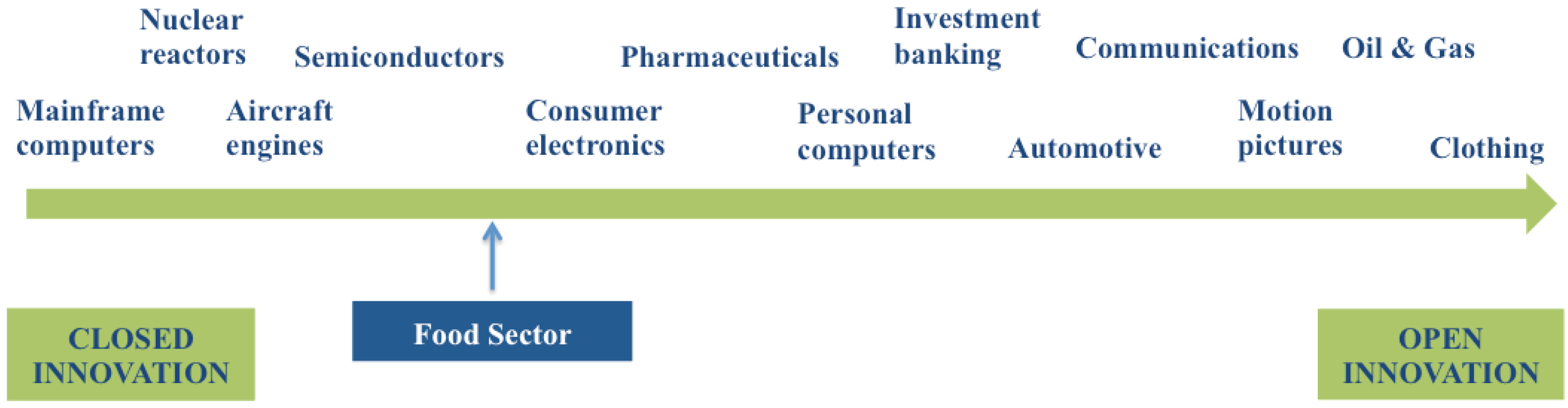

2.3. Open Innovation in the Food Sector

- -

- A different nature of food demand.

- -

- A different organization of food supply.

- -

- A more differentiated demand from consumers in terms of quality, variety and convenience.

- -

- A different demand for healthy food with a low ecological impact.

- -

- A different approach to food safety.

3. Research Design

3.1. Aims and Methodology

- -

- How are companies applying an open sustainability innovation approach?

- -

- Why are companies applying an open sustainability innovation approach?

3.2. The Sample

4. Findings

Empirical Evidence

| Company | OI Project | OI Tools | Sustainability’s Projects | Innovation Types | Supporting Technology | Scopes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starbucks | Betacup Project | Crowdsourcing | Reduce paper cup waste | Incremental | Karma Cup, a low-tech chalkboard solution | Lower time to market—Reduce use of paper cups |

| BTTR | AquaFarm | Crowdfunding | Growing home food from waste | Incremental | Home Aquaponics Kits | Grow at home food—Reduce waste Fund the production—Lower time to market—Green Jobs |

| Bubbly Dynamics LLC | The Plant | Food startups incubator | “All food waste generated by these businesses will be processed in an onsite anaerobic digester to create biogas for The Plant’s renewable energy system”[90] | Incremental | Sustainable—Food Startup—Businesses—Incubator | Food waste processed into The Plant renewable energy system—Lower operating costs—Startups become sustainable ventures |

| Unilever | Open Innovation Platform | Strategic Alliances—Crowdsourcing | Innovations can help to provide alternative solution to conventional salt | Incremental | Open innovation web platform | Reduction of salt level—higher attention to social aspects of sustainability—Find new technologies and innovations—Better understand customer needs |

| Nestlé (Nespresso) | Ecolaboration | Strategic Alliances | Ecolaboration aims to improve the Nespresso’s sustainability performances through collaboration | Incremental | Network | Higher suitability performances—Farmers are paid—Green use of 80% of the coffee beans |

| Coca-Cola | CCE’s Recycle for the Future | Collaboration with University of Exeter—Strategic alliance with OpenIDEO.com—Crowdsourcing | Understand home recycling customer behaviors—Help improve at-home recycling habits | Incremental | Research and 11-week challenge | “Help improve recycling rates at-home” |

| Kraft | Strategic Alliance with TerraCycle | collect used Capri Sun drinks pouches for upcycling and managing packaging waste | Incremental | Network | Upcycling and managing packaging waste—Speed up innovation and company growth | |

| Molinos Rio de la Plata | Open Innovation Plan | Crowdsourcing | “improve the organoleptic properties and the nutritional value of our products by making them healthier” | Incremental | Open innovation web platform | Healthier food products for better social sustainability |

| Zero Carbon Food | Growing Underground SW4 | Equity Crowdfunding | Growing food, revaluing abandoned locations underground | Incremental | “Low-energy LED lights and an integrated hydroponics system” | Food waste reduction—Contribute to reducing the cities carbon footprint—Water savings—Lower time to market |

| Tate and Lyle | Open Innovation Platform | Strategic Alliances | Health and wellness food products for: high dietary fiber ingredients with high digestive tolerance, ingredients that can replace or at least reduce salt in food, food ingredients that are able to reduce blood glucose response to food intake | Incremental | Open innovation web platform | Healthier food products for better social sustainability |

5. Conclusions and Possible Future Developments

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martinez, M.G. (Ed.) Open Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. XXXIII–XXXIV.

- Arcese, G.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Merli, R. Social life cycle assessment as a management tool: Methodology for application in tourism. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3275–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pujari, D. Mainstreaming green product innovation: Why and how companies integrate environmental sustainability. J. Bus. Eth. 2010, 95, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.; Costa, A.I. Dynamics of open innovation in the food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 19, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, F.M.; Peattie, K. Sustainability Marketing: A Global Perspective; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Report Linker. Global Food Industry. Food Industry Market Research & Statistics, 2014. Available online: http://www.reportlinker.com/ci02024/Food.html (accessed on 23 September 2014).

- Lehmann, R.J.; Reiche, R.; Schiefer, G. Future internet and the agri-food sector: State-of-the-art in literature and research. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2012, 89, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAA (Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association). Annual Report 2009; Confederation of the Food and Drink Industries in Europe (CIAA): Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- FoodDrinkEurope. 2013–2014 Data & Trends of the European Food and Drink Industry. 2014. Available online: http://www.fooddrinkeurope.eu/uploads/publications_documents/Data__Trends_of_the_European_Food_and_Drink_Industry_2013-2014.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2014).

- Fritz, M.; Schiefer, G. Food chain management for sustainable food system development: A European research agenda. Agribusiness 2008, 24, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beulens, A.J.M.; Broens, D.-F.; Folstar, P.; Hofstede, G.J. Food safety and transparency in food chains and networks—Relationships and challenges. Food Control 2005, 16, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, S.; Haines, M.; Arfini, F. Food SME networks: Process and governance—The case of Parma ham. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2003, 3, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAA (Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association). Report on Data and Trends of the EU Food and Drink Industry; Confederation of the Food and Drink Industries in Europe (CIAA): Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dagevos, H.; Bunte, F. Expanding the size of the envelope that contains agriculture. In The Food Economy—Global Issues and Challenges; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- FoodDrinkEurope. Data & Trends of the European Food and Drink Industry 2012. Available online: http://www.fooddrinkeurope.eu/uploads/publications_documents/Data__Trends_(interactive).pdf (accessed on 30 September 2014).

- Kühne, B.; Vanhonacker, F.; Gellynck, X.; Verbeke, W. Innovation in traditional food products in Europe: Do sector innovation activities match consumers’ acceptance? Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAA (Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association). European Technology Platform on Food for Life: Strategic Research Agenda 2007–2020; Confederation of the Food and Drink Industries in Europe (CIAA): Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbinge, R.; Linnemann, A. European Food Systems in a Changing World; European Science Foundation: Strasbourg, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F.; Marolla, G.; Verbano, C. Factors affecting technology transfer offices’ performance in the Italian food context. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 27, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguy, I.S.; Sirotinskaya, V. Challenges in exploiting open innovation’s full potential in the food industry with a focus on small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 38, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorriston, S. Why should imperfect competition matter to agricultural economists? Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2002, 29, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F. Models of adoption of open innovation within the food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 30, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.; Rickert, U.; Schiefer, G. Trust and risk in business networks. In Proceedings of the 99th European Seminar of the European Association of Agricultural Economists, Bonn, Germany, 8–10 February 2006.

- Kjaernes, U.; Harvey, M.; Warde, A. Trust in Food: A Comparative and Institutional Analysis; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, D.; Molina, A. Collaborative networked organizations and customer communities: value co-creation and co-innovation in the networking era. Prod. Plan. Control 2011, 22, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, R. Empirical study on sources of innovation in international food and beverage industry. Agribusiness 1996, 12, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.; Harmser, H.; Meulenberg, M.; Kuiper, E.; Ottowitz, T.; Declerck, F.; Traill, B.; Göransson, G. A framework for analysing innovation in the food sector. In Product and Process Innovation in the Food Industry; Traill, B., Grunert, K.G., Eds.; Blackie Academic and Professional: London, UK, 1997; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Traill, W.B.; Meulenberg, M. Innovation in the food industry. Agribusiness 2002, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rama, R. (Ed.) Handbook of Innovation in the Food and Drink Industry; Haworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- Capitanio, F.; Coppola, A.; Pascucci, S. Indications for drivers of innovation in the food sector. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 820–838. [Google Scholar]

- Bayona-Sáez, C.; García-Marco, T.; Sanchez-García, M. The impact of open innovation on innovation performance: The case of Spanish agri-food firms. In Open Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry; Martinez, M.G., Ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 74–94. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M.G.; Burns, J. Sources of technological development in the Spanish food and drink industry. A “supplier dominated” industry? Agribusiness 1999, 15, 431–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galizzi, G.; Venturini, L. Product innovation in the food industry: Nature, characteristics and determinants. In Economics of Innovation: The Case of the Food Industry; Galizzi, G., Venturini, L., Eds.; Physica-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar]

- Trijp, H.C.M.V.; Steenkamp, J.E.M. Consumer-oriented new product development: Principles and practice. In Innovation of Food Production Systems: Product Quality and Consumer Acceptance; Jongen, W.M.F., Meulenberg, M.T.G., Eds.; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1998; pp. 37–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, M.; Linnemann, A.R. Product development in the food industry. In Innovation of Food Production Systems: Product Quality and Consumer Acceptance; Jongen, W.M.F., Meulenberg, M.T.G., Eds.; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1998; pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.I.A.; Dekker, M.; Jongen, W.M.F. Quality function deployment in the food industry: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2000, 11, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batterink, M.H.; Wubben, B.F.M.; Omta, S.W.F. Factors related with innovate output in the Dutch agrifood industry. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2006, 6, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuin, F.T.J.M.; Omta, S.W.F. Innovations drivers and barriers in food processing. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 839–851. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reisch, A.L.; Gerd, S. Sustainable Food Systems. Available online: http://www.scp-knowledge.eu/sites/default/files/knowledge/attachments/KU_Sustainable_Food_Systems.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2014).

- Veleva, V.; Ellenbecker, M. A proposal for measuring business sustainability. Gr. Manag. Int. 2000, 31, 101–120. [Google Scholar]

- Figge, F.; Hahn, T. Sustainable value added—Measuring corporate contributions to sustainability beyond eco-efficiency. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

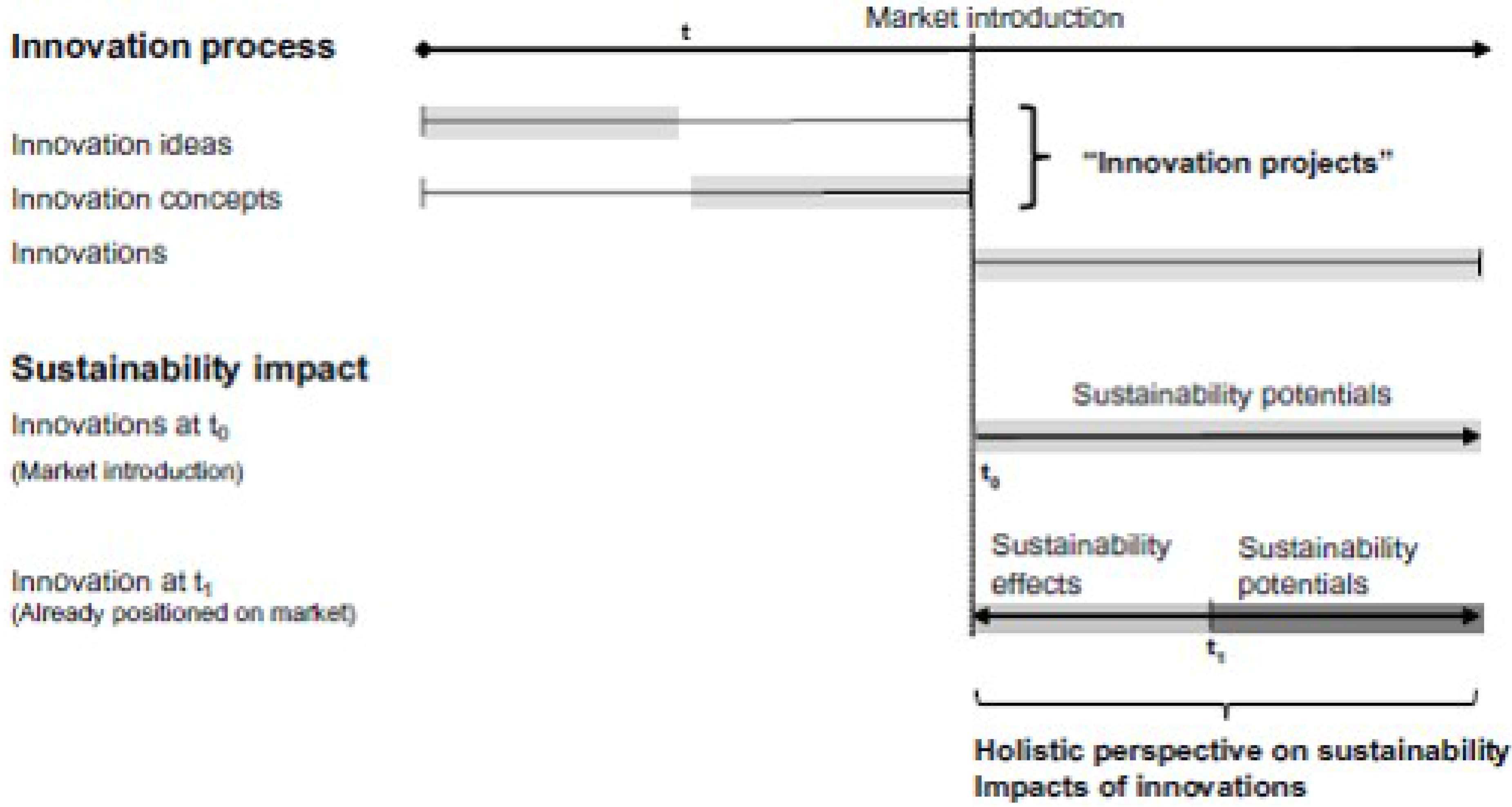

- Christiansen, A.C.; Buen, J. Managing environmental innovation in the energy sector: The case of photovoltaic and wave power development in Norway. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2001, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, B. The transformation of open source software. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 587–598. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; Volume 383. [Google Scholar]

- Harte, M.J. Ecology, sustainability, and environment as capital. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 15, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prugh, T.; Costanza, R.; Cumberland, J.H.; Daly, H.E.; Goodland, R.; Norgaard, R.B. Natural Capital and Human Economic Survival, 2nd ed.; Lewis Publishers: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D. The capital theory approach to sustainability: A critical appraisal. J. Econ. Issues 1997, 31, 145–173. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Daly, H. Natural capital and sustainable development. Conserv. Biol. 1992, 6, 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwick, J. Intergenerational equity and the investing of rents from exhaustible resources. Am. Econ. Rev. 1977, 67, 972–974. [Google Scholar]

- Solow, R. On the intertemporal allocation of natural resources. Scand. J. Econ. 1986, 88, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D. Economics, equity and sustainable development. Futures 1988, 20, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.; Atkinson, G. The concept of sustainable development: An evaluation of its usefulness ten years after Brundtland. Swiss J. Econ. Stat. 1998, 134, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callens, I.; Tyteca, D. Towards indicators of sustainable development for firms: A productive efficiency perspective. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 28, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.G. Co-creation of value by open innovation: Unlocking new sources of competitive advantage. Agribusiness 2014, 30, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. The Future of Competition: Co-Creating Value with Customers; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, J.M. Seligman lecture 2005 food product engineering: Building the right structures. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Sustainability in the food sector: A consumer behavior perspective. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, T. Food sustainability: Problems, perspectives and solutions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). In Food Wastage Footprint Impacts on Natural Resources; Technical Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Lee, M.A. Review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E.R. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Social Accountability International (SAI). Abridged Guidance—2008 Standard, February 2011. Available online: http://www.sa-intl.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID=1095 (accessed on 26 September 2014).

- Benoît, C.; Norris, G.; Valdivia, S.; Ciroth, A.; Moberg, Å.; Bos, U.; Prakash, S.; Ugaya, C.; Beck, T. The guidelines for social life cycle assessment of products: Just in time! Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, S. Creating the Big Shift: System Innovation for Sustainability; Forum for the Future: London, UK, 2013; pp. 2–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, S.J.; Campbell, B.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Climate change and food systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt Rivera, X.C.; Espinoza Orias, N.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental impacts of convenience food: Comparison of ready and home-made meals. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of Food and Agriculture. Executive Summary; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tukker, A.; Huppes, G.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; de Koning, A.; van Oers, L.; Suh, S.; Geerken, T.; van Holderbeke, M.; Jansen, B.; et al. Analysis of the Life Cycle Environmental Impacts Related to the Final Consumption of the EU-25; Main Report; Institute for Prospective Technological Studies: Sevilla, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arcese, G.; Flammini, S.; Martucci, O. Dall’Innovazione Alla Startup—L’esperienza D’imprenditori Italiani in Italia e in California; McGraw-Hill: Milan, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hippel, E. Comment on “Is open innovation a field of study or a communication barrier to theory development?”. Technovation 2010, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassiman, B.; Veugelers, R. In search of comple-mentarity in innovation strategy: Internal R&D and external knowledge acquisition. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Beamish, P.W.; Lupton, N.C. Managing joint ventures. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2009, 23, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindley, P.C.; Teece, D.J. Managing intellectual capital: Licensing and cross-licensing in semiconductors and electronics. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1997, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassmann, O. Opening up the innovation process: Towards an agenda. R&D Manag. 2006, 36, 223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler, U. Open innovation: Past research, current debates, and future directions. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2011, 25, 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Flammini, S.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Martucci, O. The evolution of open innovation in large firms. In Proceedings of the 19th IGWT Symposium on Commodity Science in Research and Practice—Current achievements and Future Challenges, Cracow, Poland, 15–19 September 2014.

- Gassmann, O.; Enkel, E. Constituents of open innovation: Three core process archetypes. R&D Manag. 2006, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gellynck, X.; Vermeire, B.; Viaene, J. Innovation in food firms: Contribution of regional networks within the international business context. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2007, 19, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omta, O.S. Innovation in chains and networks. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2002, 2, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühne, B.; Lefebvre, V.; Gellynck, X. Knowledge exchange in innovation networks: How networks support open innovation in food SMEs. Proc. Food Syst. Dyn. 2013, 73, 181–196. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarotti, V.; Manzini, R. Open innovation in the food and drink industry. Available online: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:VNwDNum1cPEJ:www.va.camcom.it/files/innovaz/I20_InterventoLIUC_OpenInnAgrofood.pptx+&cd=1&hl=it&ct=clnk&gl=it (accessed on 1 October 2014).

- Vanhaverbeke, W.P.M.; de Rochemont, M.H.; Meijer, E.; Roijakkers, A.H.W.M. Open Innovation in the Agri-Food Sector; TransForum: Cologne, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.I.; Jongen, W.M.F. New insights into consumer-led food product development. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Crowther, A.K. Beyond high tech: Early adopters of open innovation in other industries. R&D Manag. 2006, 36, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F. Innovation Trends in the food industry: The case of functional foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 31, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avermaete, T.; Viaene, J. On innovation and meeting regulation: The case of the Belgian food industry. In Proceedings of the DRUID Summer Conference on Industrial Dynamics of the New and Old Economy: Who is Embracing Whom? Copenhagen, Denmark, 6–8 June 2002.

- Acosta, M.; Coronado, D.; Ferrándiz, E. Trends in the acquisition of external knowledge for innovation in the food industry. In Open Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry; Martinez, M.G., Ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, S.E. Consumers as part of food and beverage industry innovation. In Open Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry; Martinez, M.G., Ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Baregheh, A.; Rowley, J.; Sambrook, S. Towards a multidisciplinary definition of innovation. Manag. Decis. 2009, 47, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from case studies: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stake, R. Multiple Case Study Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 342. [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamson, S.; Ryder, P.; Unterberg, B. Crowdstorm: The Future of Innovation, Ideas, and Problem Solving; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

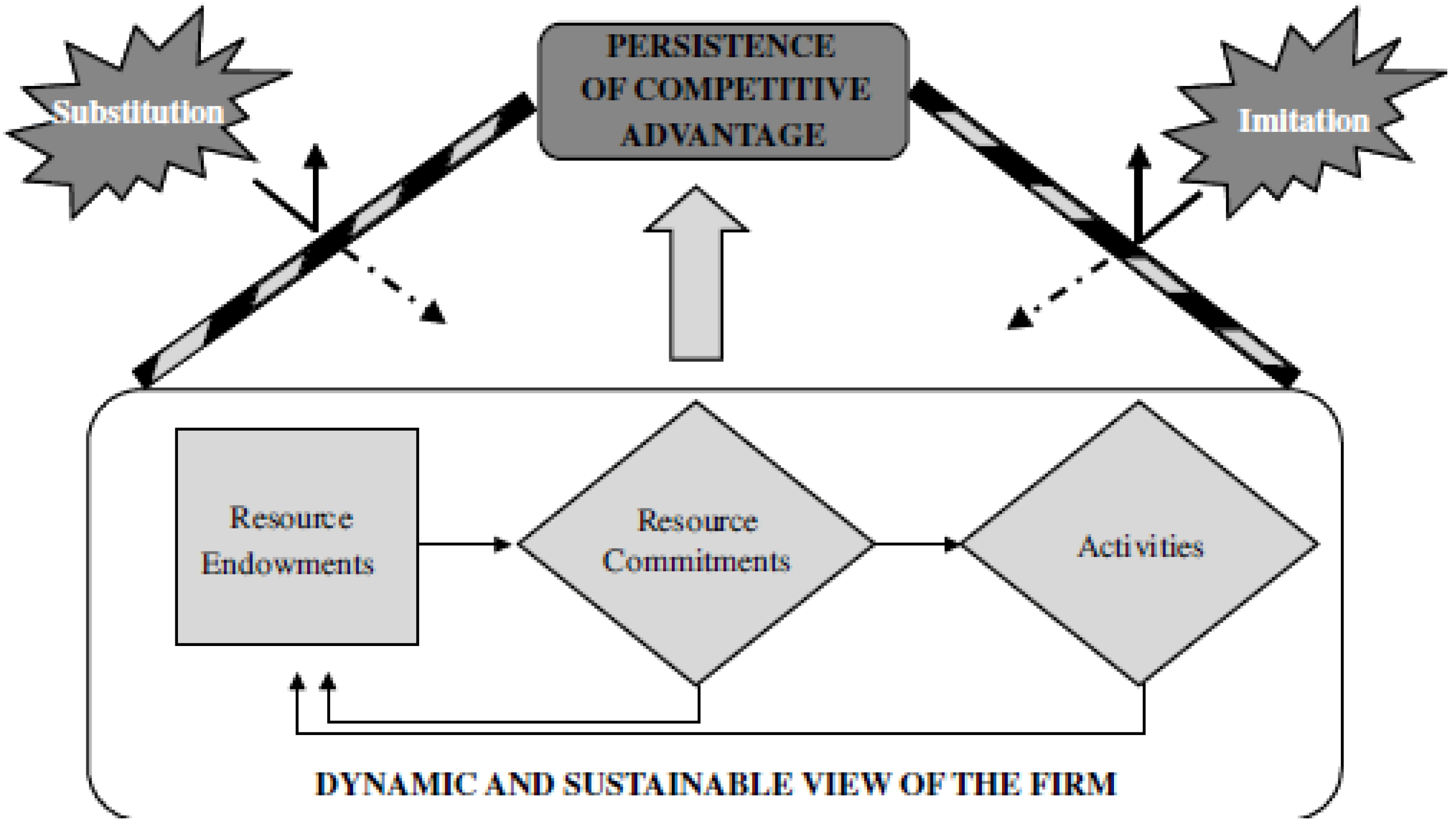

- Rodriguez, M.A.; Ricart, J.E.; Sanchez, P. Sustainable development and the sustainability of competitive advantage: A dynamic and sustainable view of the firm. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2002, 11, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betacup Project. Available online: https://betacup.jovoto.com/ideas/4751 (accessed on 30 September 2014).

- Back to the Roots. Available online: https://www.backtotheroots.com/ (accessed on 30 September 2014).

- Elks, J. Back to the Roots Growing Food Education, Reducing Waste Thanks to Smart Design. Available online: http://www.sustainablebrands.com/news_and_views/waste_not/back-roots-growing-food-education-reducing-waste-thanks-smart-design (accessed on 30 September 2014).

- Kickstarter Inc. Available online: https://www.kickstarter.com/?ref=nav (accessed on 22 June 2015).

- Arora, N.; Velez, A. Home Aquaponics Kit: Self-Cleaning Fish Tank That Grows Food; Kickstarter Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The Plant. Available online: http://www.plantchicago.com/ (accessed on 30 September 2014).

- Venie, E. The Plant. Iitmagazine, 2012. Available online: http://www.iit.edu/magazine/winter_2012/article_1.shtml#top(accessed on 30 September 2014). [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Thomas, C. Unilever Outline New Open Innovation “Challenges and Wants”. Available online: http://www.foodnavigator.com/Business/Unilever-outlines-new-open-innovation-challenges-and-wants (accessed on 29 May 2015).

- Unilever. 2015. Available online: http://www.unilever.com/about/innovation/open-innovation/ (accessed on 29 May 2015).

- Nestlé in Society. Available online: http://www.nestle.com/asset-library/documents/library/documents/corporate_social_responsibility/nestle-csv-full-report-2012-en.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2015).

- Coca-Cola Sustainability Report 2013. Available online: http://assets.coca-colacompany.com/44/d4/e4eb8b6f4682804bdf6ba2ca89b8/2012-2013-gri-report.pdf (accessed on 29 May 2015).

- Thota, H. Kraft and Unilever pathways to innovative leadership. Innov. Beverage Innov. 2012, 10, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- NineSights. Available online: https://ninesights.ninesigma.com/web/kraft-gallery (accessed on 30 May 2015).

- Molinos Rio de la Plata. Available online: https://ninesights.ninesigma.com/web/kraft-gallery (accessed on 30 May 2015).

- Zero Carbon Food. 2015. Available online: http://www.zerocarbonfood.co.uk (accessed on 30 May 2015).

- Rayapura, A. Startup Growing “Zero Carbon Food” in London Underground Tunnels Has Investors Clamoring Sustainable Brands the Bridge to Better Brands, 2014. Available online: http://www.sustainablebrands.com/news_and_views/startups/aarthi_rayapura/startup_growing_zero_carbon_food_london_underground_tunnels_ (accessed on 29 May 2015).

- Tate & Lyle. 2014. Available online: http://www.tateandlyleopeninnovation.com/Pages/Home.aspx (accessed on 30 May 2015).

- Chesbrough, H. Open Business Models: How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; p. xii. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Food Market Overview. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/sectors/food/eu-market/index_en.htm (accessed on 30 September 2014).

- Wielens, R. Accelerating the innovation cycle through intermediation: The case of Kraft’s melt-proof chocolate bars. In Open Innovation in the Food and Beverage Industry; Martinez, M.G., Ed.; Elsevier: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 62–73. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arcese, G.; Flammini, S.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Martucci, O. Evidence and Experience of Open Sustainability Innovation Practices in the Food Sector. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8067-8090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7078067

Arcese G, Flammini S, Lucchetti MC, Martucci O. Evidence and Experience of Open Sustainability Innovation Practices in the Food Sector. Sustainability. 2015; 7(7):8067-8090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7078067

Chicago/Turabian StyleArcese, Gabriella, Serena Flammini, Maria Caludia Lucchetti, and Olimpia Martucci. 2015. "Evidence and Experience of Open Sustainability Innovation Practices in the Food Sector" Sustainability 7, no. 7: 8067-8090. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7078067