Scaling-up Strategy as an Appropriate Approach for Sustainable New Town Development? Lessons from Wujin, Changzhou, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Scale and Scaling-up in the Context of Chinese Urban Development

3. Study Area and a Case Study Method

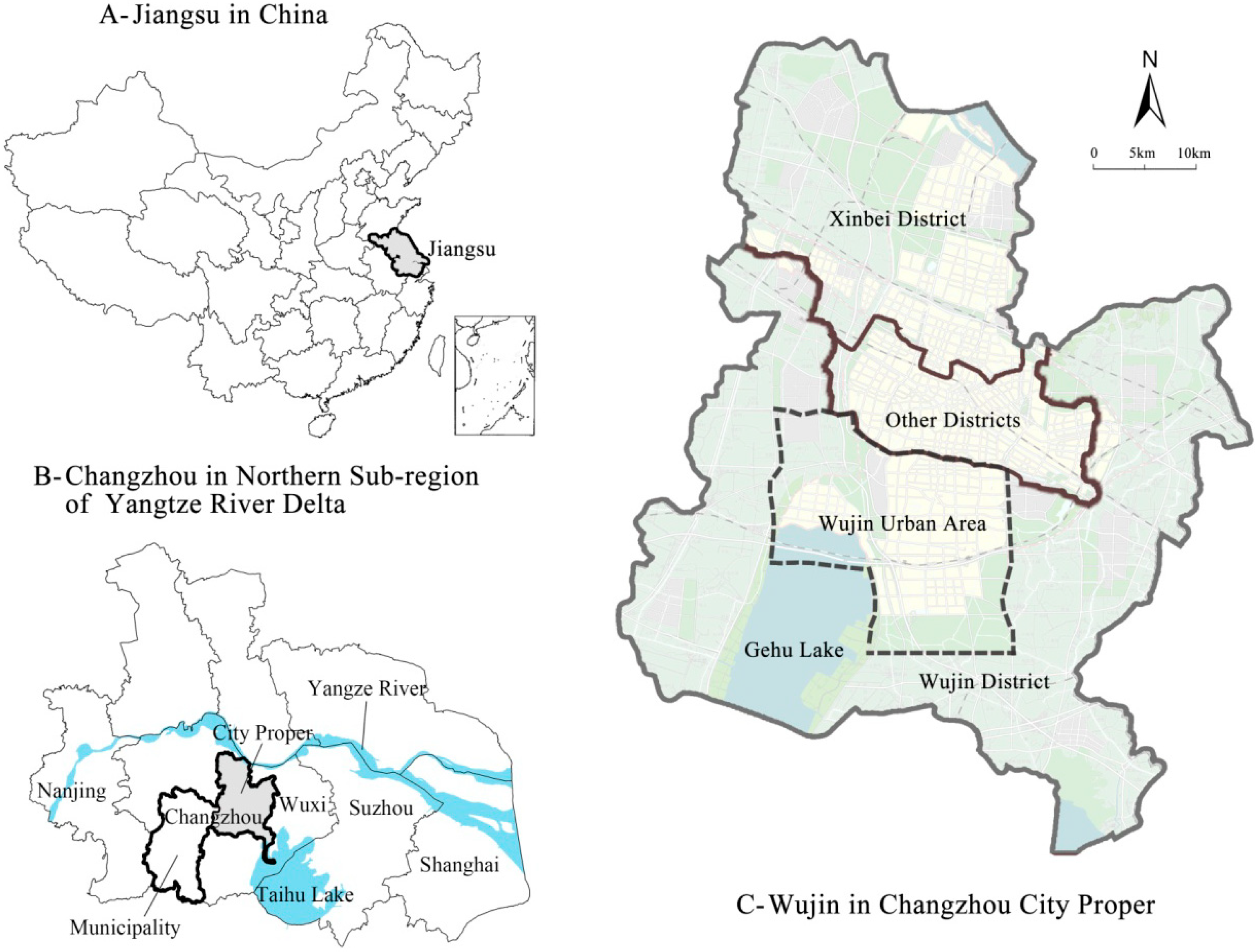

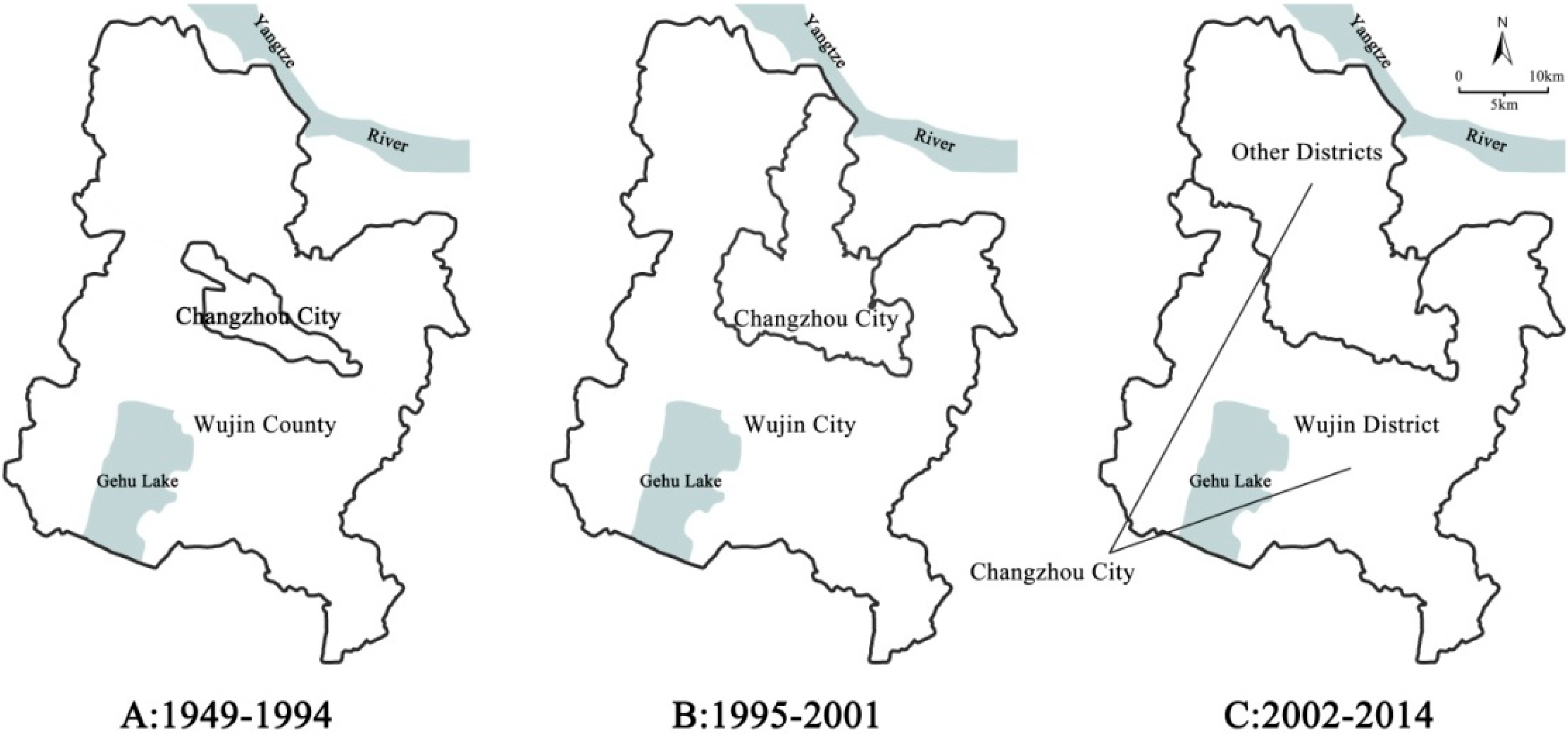

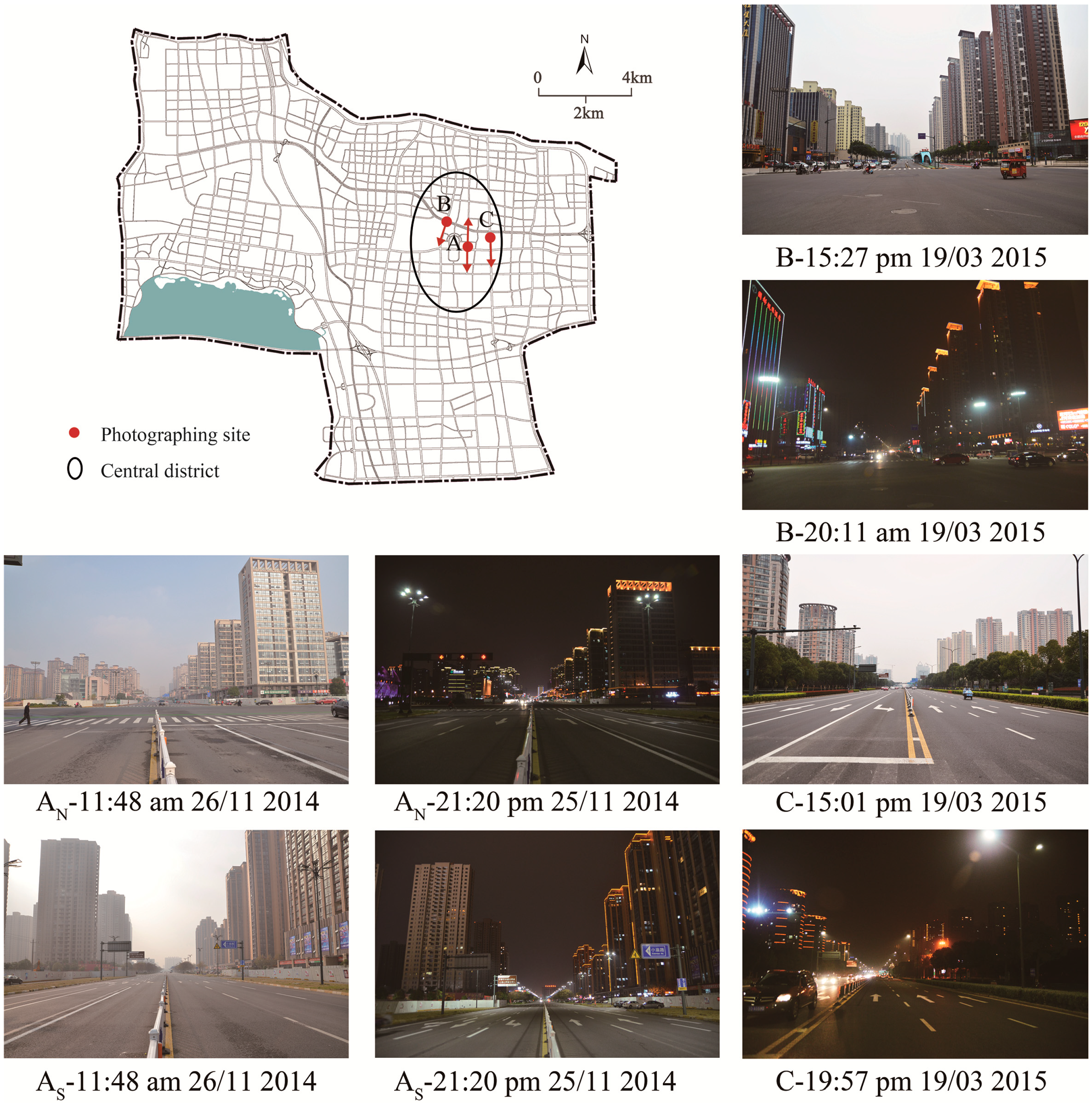

3.1. Study Area

3.2. A Case Study Method

4. The Practices of Scaling-up Planning in Three Phases

4.1. Is it Another “Great Leap Forward”?

4.1.1. Bottom-up Urbanization Before 2003

4.1.2. Scaling-up Formation During 2003 to 2013

4.1.3. Scale-Jumping Strategy Based Planning Agenda (2003–2009)

4.1.4. Scale-Penetration Based Planning and Overlapping Scale Redemption Agenda (2009–2013)

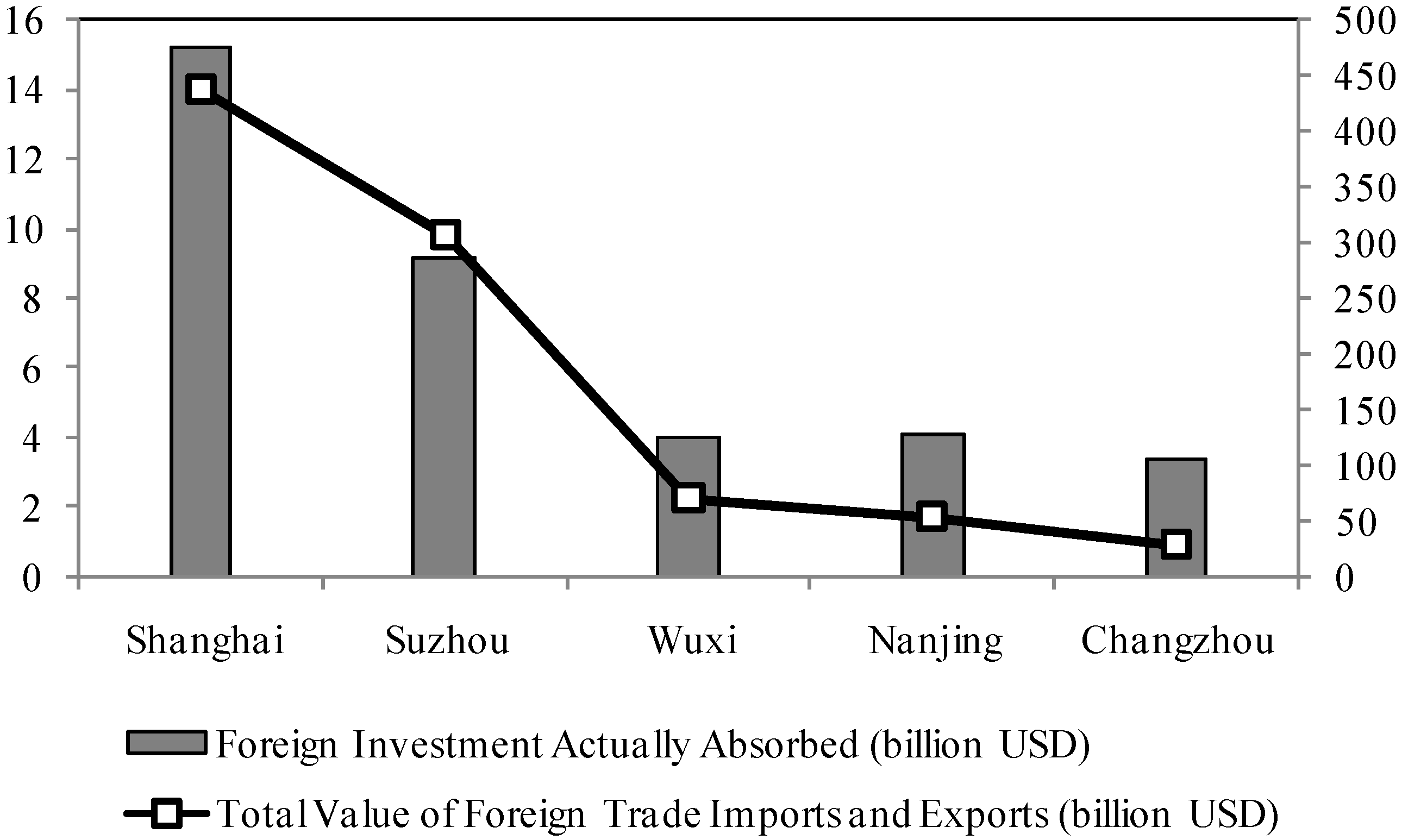

“In a flat world reconstructed by the process of globalization, the cities on the bottom of national hierarchical city system (political system or size system) could have an opportunity to fulfill important functions and play nodal roles in the global city system. Wujin, undoubtedly as such a city, is capable of penetrating into the global city system…because of its advantageous location in the Yangtze Delta and its economic strength.”—Strategic Planning Report for Wujin New City (2009–2030) [45] (also see, Interviewee E3)

4.2. Evaluating Outcomes of Scaling-up Strategies

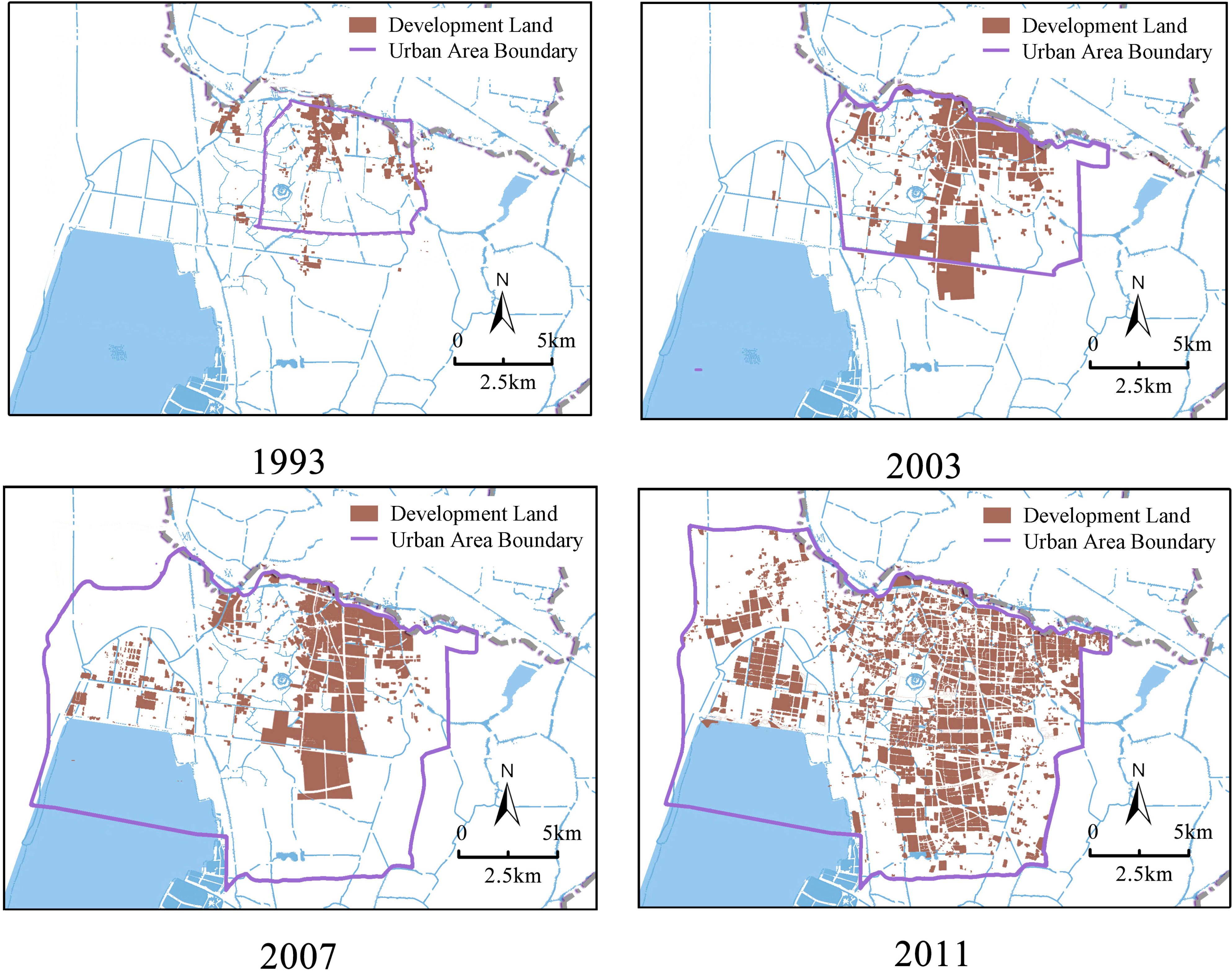

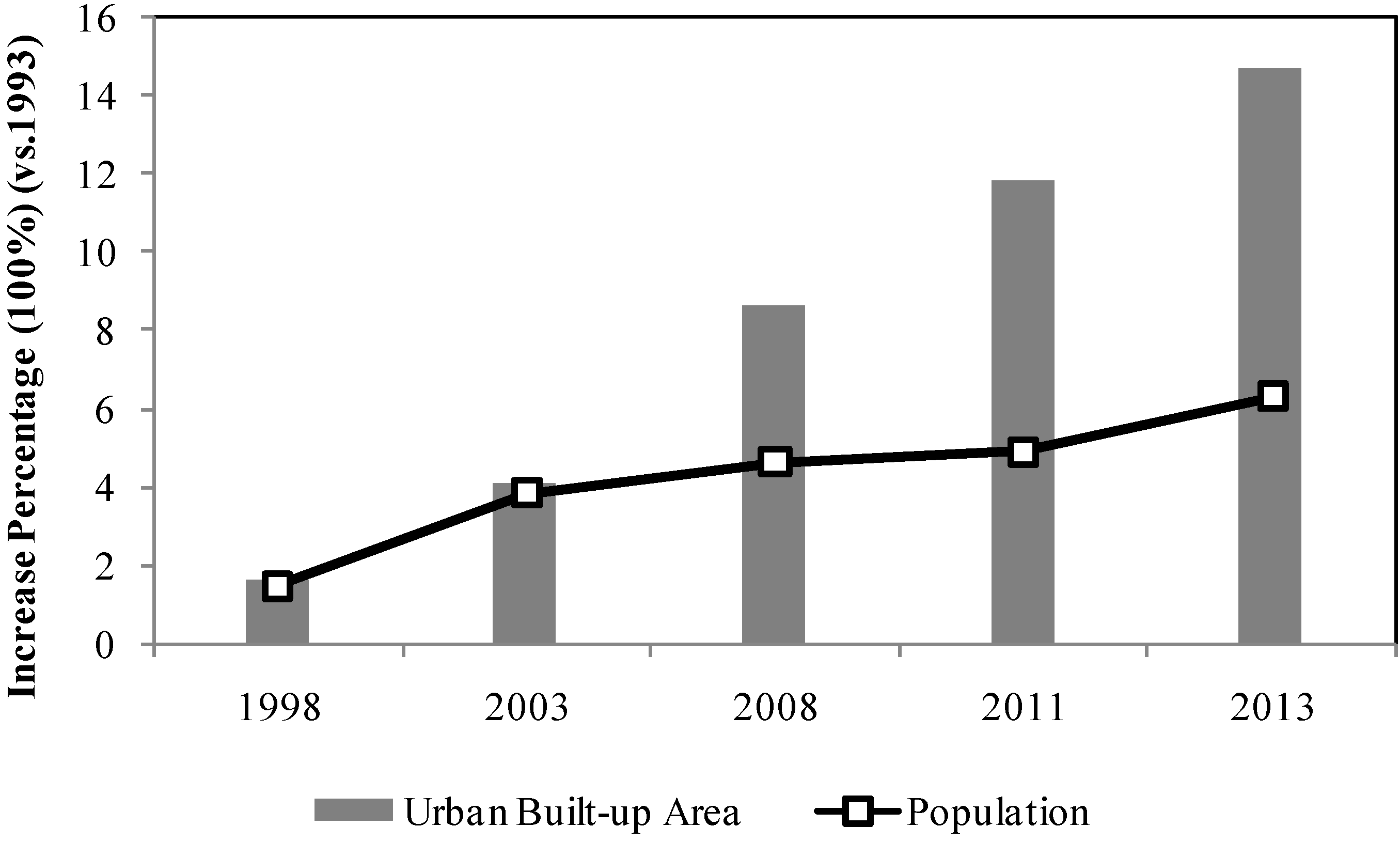

4.2.1. Consequence (or Outcome) of Great-Leap Land Consumption

4.2.2. Social-Spatial Consequence of Continuous Urban Sprawl

| Urban Land Use | 1993 (km2) | 2003 (km2) | 2013 (km2) | Growth (1993–2003) (km2) | Growth (2003–2013) (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | 4.33 | 15.61 | 33.76 | +11.28 | +18.15 |

| Manufacturing | 2.87 | 17.46 | 43.08 | +14.59 | +25.62 |

| Transport | 0.62 | 11.57 | 18.97 | +10.95 | +7.4 |

| Green land | 0 | 0.19 | 13.58 | +0.19 | +13.39 |

| Commercial and Public facilities | 1.64 | 8.53 | 13.32 | +7.49 | +4.79 |

| Zones | Construction year | Residential vacancy rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chengzhonghuayuan zone | 1990 | <10% |

| 2 | Sijixincheng zone | 2002 | 10% |

| 3 | Tian’ anbieshu zone | 2004 | 19.5% |

| 4 | Xinchengnandu zone | 2005 | 13% |

| 5 | Changhonghuayuan zone | 2006 | 43% |

| 6 | Daxuexincun zone | 2006 | 48% |

| 7 | Cailingjiayuan zone | 2006 | 30% |

| 8 | Nandianyuan zone | 2007 | 30% |

| 9 | Yucheng zone | 2007 | 30% |

| 10 | Hupanchunqiu zone | 2008 | 35% |

| 11 | Tianjuanfeng zone | 2010 | 45% |

| 12 | Hongjianyipin zone | 2010 | 50% |

| 13 | Moershangpin zone | 2010 | 66% |

| 14 | Xinchenggongguan zone | 2011 | 35% |

| 15 | Laimengcheng zone | 2011 | 50% |

| 16 | Xingheguoji zone | 2013 | 90% |

4.3. Evaluating Land Revenue Collection

5. Discussion

5.1. Dream or Nightmare? An Unbroken Bubble of Scaling-up Strategy or Planning Competitions

5.2. The development of Green Technology

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Appendix

| Venues | Data | Interviewees | Contents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Local Business Community (8 interviewees, A1–A8) | |||

| 1 | Office | 23 November 2014 | A regional manager of a nation-wide real estate company | Sales performance; business environment and future investment consideration |

| 2 | Restaurant | 23 October 2014 | A local real estate developer | The development of real estate market in Wujin |

| 3 | Marketing hall | 23 November 2014 | A sale manager of a local real estate enterprise | Sales performance recent years |

| 4 | Store | 23 November 2014 | A local small business owner | Business environment; interest of investment in real estate |

| 5 | Community | 23 November 2014 | An employee of a trans-region company | Business and living environment in Wujin |

| 6 | Scale office | 23 November 2014 | A branch manager of a second-hand property agency | Business performance and appraisal over the second real estate market of Wujin |

| 7 | Park | 23 November 2014 | A shopkeeper in a community store | Business performance recent years |

| 8 | Restaurant | 23 November 2014 | A manager of a restaurant in the central business district (CBD) | Business performance; business environment in Wujin |

| B | Officials (7 interviewees, B1–B7) | |||

| 1 | Restaurant | 23 October 2014 | An official of tourism bureau, Wujin | Developing issue of Wujin; problems in restructuring economy |

| 2 | Restaurant | 23 October 2014 | An alcalde | Developing issue of Wujin, opinions on scale overlapping strategy from a Wujin perspective |

| 3 | Hotel | 22 November 2014 | An official in a functional zone | Finance issue of Wujin |

| 4 | Office | 24 November 2014 | Official A in a department of district government | History of planning-making |

| 5 | Office | 24 November 2014 | Official B in a department of district government | “Green” strategy in planning |

| 6 | Office | 24 November 2014 | An vice-director of a planning institute in Wujin | Problems of excessive land consuming |

| 7 | Office | 24 November 2014 | An official of planning bureau, Changzhou | Conflicts of spatial development strategies between Changzhou and Wujin; opinions on scale overlapping strategy from a Changzhou perspective |

| C | Local residents and managers of community property management companies (23 interviewees) (C1–C23) | |||

| 1–4 | Sijixincheng zone; Chengzhonghuayuan zone; | 22 November 2014 | Two residents and two managers of property management companies | Vacancy rate; mental map; community sense; future plan of property investment |

| 5–10 | Nandianyuan zone; tianjuanfeng zone; xinchengnandu zone; xinchengnandu zone | 22 November 2014 | Three residents and three managers of property management companies | Vacancy rate; mental map; community sense; future plan of property investment |

| 11–16 | Laimengcheng zone; Xingheguoji zone; Moershangpin zone | 22 November 2014 | Three residents and three managers of property management companies | Vacancy rate; mental map; community sense; future plan of property investment |

| 17–23 | Other 8 zones | 22 November 2014 | One resident or manager of property management company in each zone | Vacancy rate |

| D | Migrant workers (7 interviewees) (D1–D7) | |||

| 1–3 | Taxi; hotel; restaurant | 23 November 2014 | Three migrant workers in service sector | Attraction of Wujin’s living environment and their settlement plans; mental map |

| 4–5 | Street; store | 23 November 2014 | Two migrant workers in manufacturing sector | Attraction of Wujin’s living environment and their settlement plans; mental map |

| 6–7 | open spaces | 23 November 2014 | two migrant worker in high-tech industries | Attraction of Wujin’s living environment and their settlement plans; mental map |

| E | planners (4 interviewees) (E1–E4) | |||

| 1 | In a meeting | 15 October 2009 | A planner joined in the master planning 1993 | Details of the planning process |

| 2 | By telephone | 26 November 2014 | A planner joined in the strategic planning 2003 | Details of the planning process |

| 3 | In university | 4 November 2014 | A planner joined in the strategic planning 2009 | Details of the planning process |

| 4 | By telephone | 26 November 2014 | A planner in a state-run planning institute of Changzhou | Opinions on scale overlapping strategy from a Changzhou perspective |

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howitt, R. Scale. In A Companion to Political Geography; Agnew, J., Mitchell, K., O’Tuathail, G., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 138–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. Scale. In The Dictionary of Human Geography, 4th ed.; Johnston, D., Gregory, G., Pratt, G., Watts, M., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000; pp. 724–727. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, S.A. The social construction of scale. Prog. Human Geogr. 2000, 2, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, S.A.; Jones, J.P.; Woodward, K. Human geography without scale. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2005, 4, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, W.; McGee, T.G. Theatres of Accumulation: Studies in Asian and Latin American Urbanization; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, P.; Acs, Z.J. Globalization: countries, cities and multinationals. Reg. Stud. 2011, 1, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cheng, Y.; Yin, J.; Wang, Y. Province-leading-county as a scaling-up strategy in China: The case of Jiangsu. China Rev. 2014, 1, 125–146. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. Scale, state and the city: Urban transformation in post-reform China. Habitat Int. 2007, 3, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Liu, D.; Han, L.; Yang, Y. “Kunming—A Regional International Mega city in Southwest China” in Urban Development Challenges, Risks and Resilience in Asia Mega Cities; Singh, R.B., Ed.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 323–351. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Li, S.M. Housing Inequality in Chinese Cities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.M. Housing inequalities under market deepening: The case of Guangzhou, China. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 12, 2852–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Chen, G.; Hammel, D.; Wu, X. Socio-spatial differentiation and residential segregation in the Chinese city: Based on the 2000 community-level census data: A case study of the inner city of Nanjing. Cities 2014, 39, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Bozzetti, C.; Ho, K.F.; Cao, J.J.; Han, Y.; Daellenbach, K.R.; Slowik, J.G.; Platt, S.M.; Canonaco, F.; et al. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature 2014, 514, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, H. Size and Characteristic of Housing Bubbles in China’s Major Cities: 1999–2010. China World Econ. 2011, 6, 56–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W. What kind of a science is sustainability science? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 49, 19449–19450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Geography, difference and the politics of scale. In Postmodernism and the Social Sciences; Doherty, J., Graham, E., Malek, M., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1992; pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1984; pp. 34–65. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Neither global nor local: “Globalization” and the politics of scale. In Spaces of Globalization; Cox, K.R., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 137–166. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Scaled and geographies: Nature, place, and the politics of scale. In Scale and Geographic Inquiry: Nature, Society, and Method; Sheppard, E., McMaster, R.B., Eds.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. The limits to scale? Methodological reflections on scalar structuration. Prog. Human Geogr. 2001, 4, 591–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: the Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P. A materialist framework for political geography. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1982, 7, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Homeless/global: Scaling places. In Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures Global Change; Robertson, G., Tickner, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 87–120. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geogr. Ann. 1989, 1, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.C. Urban administrative restructuring, changing scale relations and local economic development in China. Polit. Geogr. 2005, 24, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H. The change in China’s state governance and its effects upon urban scale. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 789–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.C. Urban transformation in China, 1949–2000: A review and research agenda. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 1545–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J. Local growth coalition: The context and implications of China’s gradualist urban land reforms. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1999, 25, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. Urban development and a socialist pro-growth coalition in Shanghai. Urban Aff. Rev. 2002, 4, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Wu, F. Property-led redevelopment in post-reform China: A case study of Xintiandi redevelopment project in Shanghai. J. Urban Aff. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. Globalisation as reterritorialisation: The re-scaling of urban governance in the European Union. Urban Stud. 1999, 3, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Insider. Available online: http://www.businessinsider.com/pictures-chinese-ghost-cities-2010-12?slop=1#slideshow-start (accessed on 20 November 2014).

- Zhang, J.; Wu, F. China’s changing economic governance: Administrative annexation and the reorganization of local governments in the Yangtze River Delta. Reg. Stud. 2007, 1, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Y. How Reform Worked in China? In In Search of Prosperity: Analytic Narratives on Economic Growth; Rodrik, D., Ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 297–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.J.C.; Fan, M. Urbanization from below: The growth of towns in Jiangsu, China. Urban Stud. 1994, 10, 1625–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Ma, L.J.C. Urbanization from below in China: Its development and mechanisms. Acta Geogr. Sinica 1999, 2, 106–115. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Changzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics, National Bureau of Investigation Corps Changzhou. Changzhou Statistical Yearbook (2013); China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wujin Urban Planning Bureau (WUPB). Wujin County Master Planning Report (1993–2020); WUPB: Changzhou, China, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wujin Urban Planning Bureau (WUPB). Wujin District Strategic Planning Report (2003); WUPB: Changzhou, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lardy, N.R. Sustaining China’s Economic Growth after the Global Financial Crisis; Peterson Institute for International Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wujin Urban Planning Bureau (WUPB). Wujin District Strategic Planning Report (2009); WUPB: Changzhou, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, J. The world city hypothesis. Dev. Change 1986, 1, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S. Institutional innovations, asymmetric decentralization, and local economic development: A case study of Kunshan, in post-Mao China. Environ. Plan. C 2007, 25, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wujin Urban Planning Bureau (WUPB). Wujin City Strategic Planning Report (1998–2020); WUPB: Changzhou, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wujin Urban Planning Bureau (WUPB). Urban Construction Development Report of Wujin Urban Area 2013; WUPB: Changzhou, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jinling Evening News. Available online: http://jlwb.njnews.cn/html/2014-07/18/content_1659081.htm (accessed on 28 November 2014). (In Chinese)

- NetEase Finance. Available online: http://money.163.com/13/0226/08/8OKKF2EJ00253B0H.html (accessed on 28 November 2014). (In Chinese)

- Wujin Urban Planning Bureau (WUPB). 12th Five-Year Plan for Housing Development in Wujin Urban Area; WUPB: Changzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Yeh, A.G.O. City repositioning and competitiveness building in regional development: new development strategies in Guangzhou, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2005, 29, 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wujin District Bureau of Statistics, National Bureau of Investigation Corps Wujin. Wujin Statistical Yearbook (2004); Wujin District Bureau of Statistics: Changzhou, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive Department, National Bureau of Statistics (CD-NBS). China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy (2004); China Financial & Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jiangsu Province Bureau of Statistics, National Bureau of Investigation Corps Jiangsu. Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook (2004–2013); China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.C.; Yi, F. Urbanization of capital or capitalization on urban land? Land development and local public finance in urbanizing China. Urban Geogr. 2011, 1, 50–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Lichtenberg, E. Land and urban economic growth in China. J. Reg. Sci. 2011, 2, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Waley, P. Coalescing for local growth in Kunming, China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2015, unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- China Center for Urban Development (CCUD). Available online: http:// www.ccud.org.cn/2013-09-26/113349759.html (accessed on 20 November 2014).

- Shanghai Municipal Bureau of Statistics, National Bureau of Investigation Corps Shanghai. Shanghai Statistical Yearbook (2004–2013); China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2004–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, K.; Gleeson, B. The sustainability of an entrepreneurial city? Int. Plan. Stud. 2014, 2, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, E. Policy boosterism, policy mobilities, and the extrospective city. Urban Geogr. 2013, 1, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- While, A.; Jonas, A.E.; Gibbs, D. The environment and the entrepreneurial city: Searching for the urban ‘sustainability fix’ in Manchester and Leeds. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2004, 3, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ma, Z.; Song, W. Scaling-up Strategy as an Appropriate Approach for Sustainable New Town Development? Lessons from Wujin, Changzhou, China. Sustainability 2015, 7, 5682-5704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055682

Chen H, Wu Q, Cheng J, Ma Z, Song W. Scaling-up Strategy as an Appropriate Approach for Sustainable New Town Development? Lessons from Wujin, Changzhou, China. Sustainability. 2015; 7(5):5682-5704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055682

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Hao, Qiyan Wu, Jianquan Cheng, Zhifei Ma, and Weixuan Song. 2015. "Scaling-up Strategy as an Appropriate Approach for Sustainable New Town Development? Lessons from Wujin, Changzhou, China" Sustainability 7, no. 5: 5682-5704. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055682