Corporate Brand Trust as a Mediator in the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR, Corporate Hypocrisy, and Corporate Reputation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Brand Trust in CSR

2.2. The Effect of Corporate Brand Trust on the Relationship between CSR Perception and Corporate Hypocrisy

2.3. The Effect of Corporate Brand Trust on the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR and Corporate Reputation

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Participant Characteristics

3.2. Measurement Scales

4. Results

4.1. Reliability, Validity, and Common Method Bias

| Construct | λ | α | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corporate Social Responsibility | XXX (corporate name; Hyundai Motors, LG, Samsung, SK) is a socially responsible company. | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.63 |

| XXX is concerned to improve the wellbeing of society. | 0.82 | ||||

| XXX behaves responsibly regarding the environment. | 0.76 | ||||

| Corporate Brand Trust | XXX is reliable. | 0.84 | 0.73 | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| XXX is trustworthy. | 0.82 | ||||

| XXX is dependable. | 0.74 | ||||

| Corporate Hypocrisy | In my opinion, XXX acts hypocritically. | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.70 |

| In my opinion, what XXX says and does are two different things. | 0.79 | ||||

| In my opinion, XXX pretends to be something that it is not. | 0.88 | ||||

| Corporate Reputation | XXX is a company I have a good feeling about. | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.61 |

| XXX is a company that I admire and respect. | 0.75 | ||||

| XXX has a good overall reputation. | 0.83 | ||||

| χ2(48) = 113.13; p < 0.05, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.03 | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Corporate Social Responsibility | 0.63 | |||

| 2. Corporate Brand Trust | 0.44 ** | 0.64 | ||

| 3. Corporate Hypocrisy | –0.38 ** | –0.77 ** | 0.70 | |

| 4. Corporate Reputation | 0.45 ** | 0.48 ** | –0.47 ** | 0.61 |

| Mean | 2.85 | 2.86 | 2.95 | 3.43 |

| SD | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.73 |

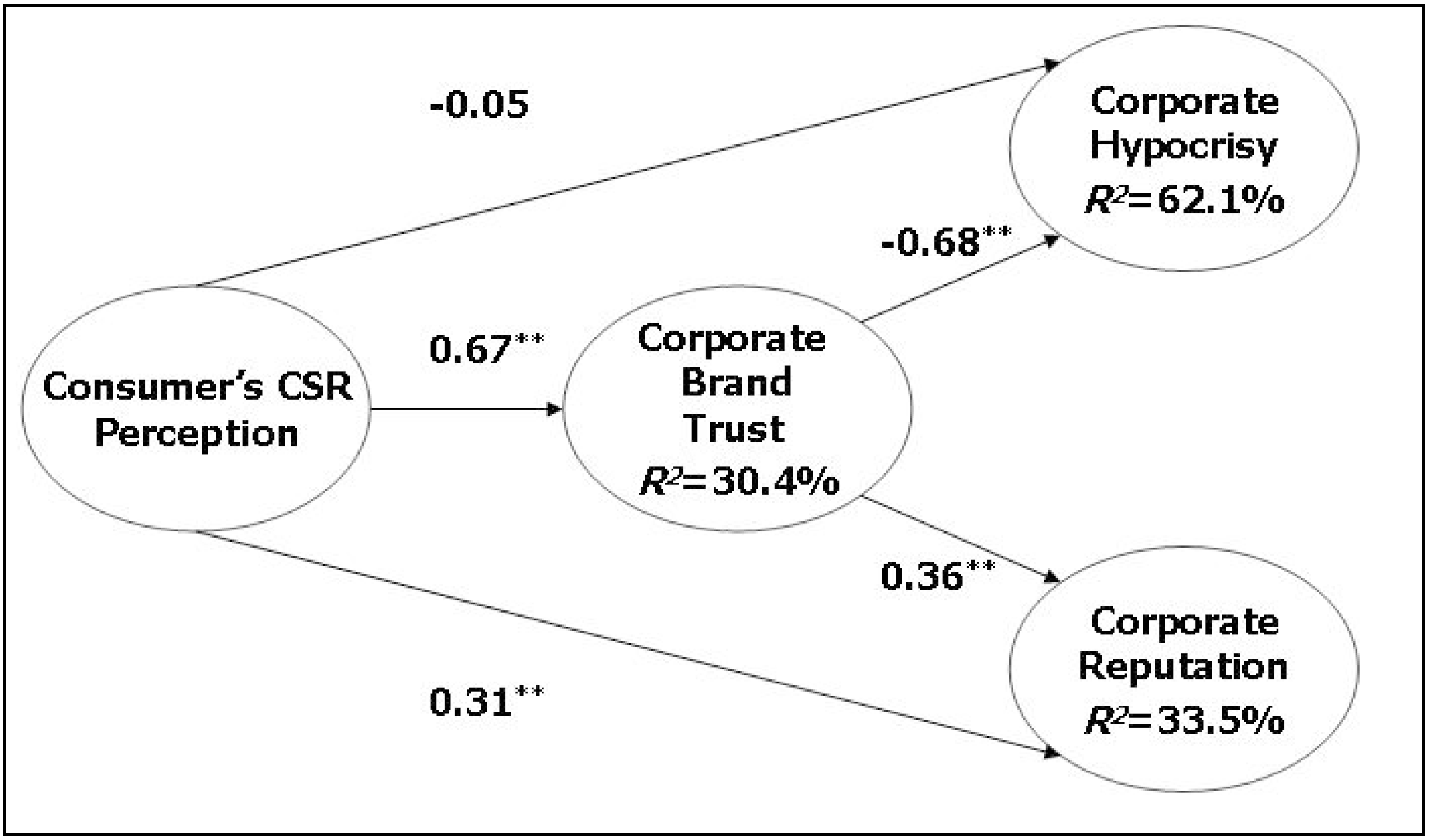

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

| Hypothesis | Effect | Path | Value | CIlow | CIhigh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Direct | Consumer’s CSR Perception → Corporate Hypocrisy | –0.046 | –0.196 | 0.096 |

| Indirect | Consumer’s CSR Perception → Corporate Brand Trust → Corporate Hypocrisy | –0.453 | –0.602 | –0.333 | |

| Total | Consumer’s CSR Perception → Corporate Hypocrisy | –0.499 | –0.655 | –0.351 | |

| H2 | Direct | Consumer’s CSR Perception → Corporate Reputation | 0.306 | 0.124 | 0.504 |

| Indirect | Consumer’s CSR Perception → Corporate Brand Trust → Reputation | 0.238 | 0.139 | 0.362 | |

| Total | Consumer’s CSR Perception → Reputation | 0.544 | 0.377 | 0.719 |

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Battacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, T.; Garrido-Morgado, A. Corporate reputation: A combination of social responsibility and industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkurinen, P. Image differentiation with corporate environmental responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K. The advertising effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate reputation and brand equity: Evidence from life insurance industry in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Chiu, C.; Yang, C.; Pai, D. The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C.; Kvasova, O.; Leonidou, C.N.; Chari, S. Business unethicality as an impediment to consumer trust: The moderating role of demographic and cultural characteristics. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaniz, E.B.; Caceres, R.C.; Perez, R.C. Alliances between brands and social causes: The influence of company credibility on social responsibility image. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Bijmolt, T.H.A.; Tribo, J.A.; Verhoef, P. Generating global brand equity through corporate social responsibility to key stakeholders. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichtmann, C. An analysis of antecedents and consequences of trust in a corporate brand. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.; Weitz, B. The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Munuera-Aleman, F.L. Does brand trust matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Newell, S.J. The dual credibility model: The influence of corporate and endorser credibility on attitudes and purchase intentions. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2002, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Donney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, L.N.; John, D.R. The development of self-brand connections in children and adolescents. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Leffler, K.B. The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. J. Polit. Econ. 1981, 89, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational image and member identification. Adm. Sci. Quart. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B.; Goldstein, H.W.; Smith, B.D. The ASA framework: An update. Pers. Psychol. 1995, 48, 747–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, S.; Misani, N.; Tencati, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: The case of organic food. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.A.; Tsamakos, A.; Vrechopoulos, A.P.; Avramidis, P.K. Corporate social responsibility: Attributions, loyalty, and the mediating role of trust. J. Acad. Market Sci. 2009, 37, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janney, J.J.; Gove, S. Reputation and corporate social responsibility aberrations, trends, and hypocrisy: Reactions to firm choices in the stock option backdating scandal. J. Manage. Stud. 2011, 48, 1562–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Battacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Reaping relational rewards from corporate social responsibility: The role of competitive positioning. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2007, 24, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimp, T.A. Advertising, Promotion, and Supplemental Aspects of Integrated Marketing Communication, 4th ed.; Dryden Press: Fort Worth, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Web, D.; Mohr, L. A typology of consumer responses to cause-related marketing; from skeptics to socially concerned. J. Public Policy Mark. 1998, 17, 226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Srinnivasan, N.; Ratchford, B.T. An empirical test of a model of external search for automobiles. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 18, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, E.; Johnson, M. The different roles of satisfaction, rust and commitment for relational and transactional consumers. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.A.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain effects form brand trust and brand effect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 31–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer-Firm identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsi, M.; Wilson, A.M. Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2001, 6, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. The Moral Dimension; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.; Van Riel, C. The reputational landscape. Corp. Reput. Rev. 1997, 1, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics. 2006, 69, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, D.; Lee, P.M.; Dai, Y. Organizational reputation: An overview. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 153–184. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R. Finding sources of brand value: Developing a stakeholder model of brand equity. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 13, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 85, 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J. The leadership challenge: Building resilient corporate reputations. In Handbook on Responsible Leadership and Governance in Global Business; Doh, J.P., Strumpf, S.A., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2005; pp. 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Osterhus, T.L. Pro-social consumer influence strategies: When and how do they work? J. Mark. 1997, 61, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.S.; Srinivasan, V. A survey-based method for measuring and understanding brand equity and its extendability. J. Mark. Res. 1994, 31, 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A. Basic Marketing Research; The Dryden Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Woo, J. How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: Mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 125, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, G.; van Riel, C.B.; van Bruggen, G.H. Corporate associations and consumer product responses: The moderating role of corporate brand dominance. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburry, W. Reputation and supportive behavior: Moderating impacts of foreignness, industry and local exposure. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 388–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, H.A.; Simmering, M.J.; Sturman, M.C. A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 12, 762–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez del Bosque, I. Customer personal features as determinants of the formation process of corporate social responsibility perceptions. Psychol. Mark. 2013, 30, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.; Hur, W.-M.; Yeo, J. Corporate Brand Trust as a Mediator in the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR, Corporate Hypocrisy, and Corporate Reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683-3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7043683

Kim H, Hur W-M, Yeo J. Corporate Brand Trust as a Mediator in the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR, Corporate Hypocrisy, and Corporate Reputation. Sustainability. 2015; 7(4):3683-3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7043683

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Hanna, Won-Moo Hur, and Junsang Yeo. 2015. "Corporate Brand Trust as a Mediator in the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR, Corporate Hypocrisy, and Corporate Reputation" Sustainability 7, no. 4: 3683-3694. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7043683