Place, Capital Flows and Property Regimes: The Elites’ Former Houses in Beijing’s South Luogu Lane

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Layered Landscapes

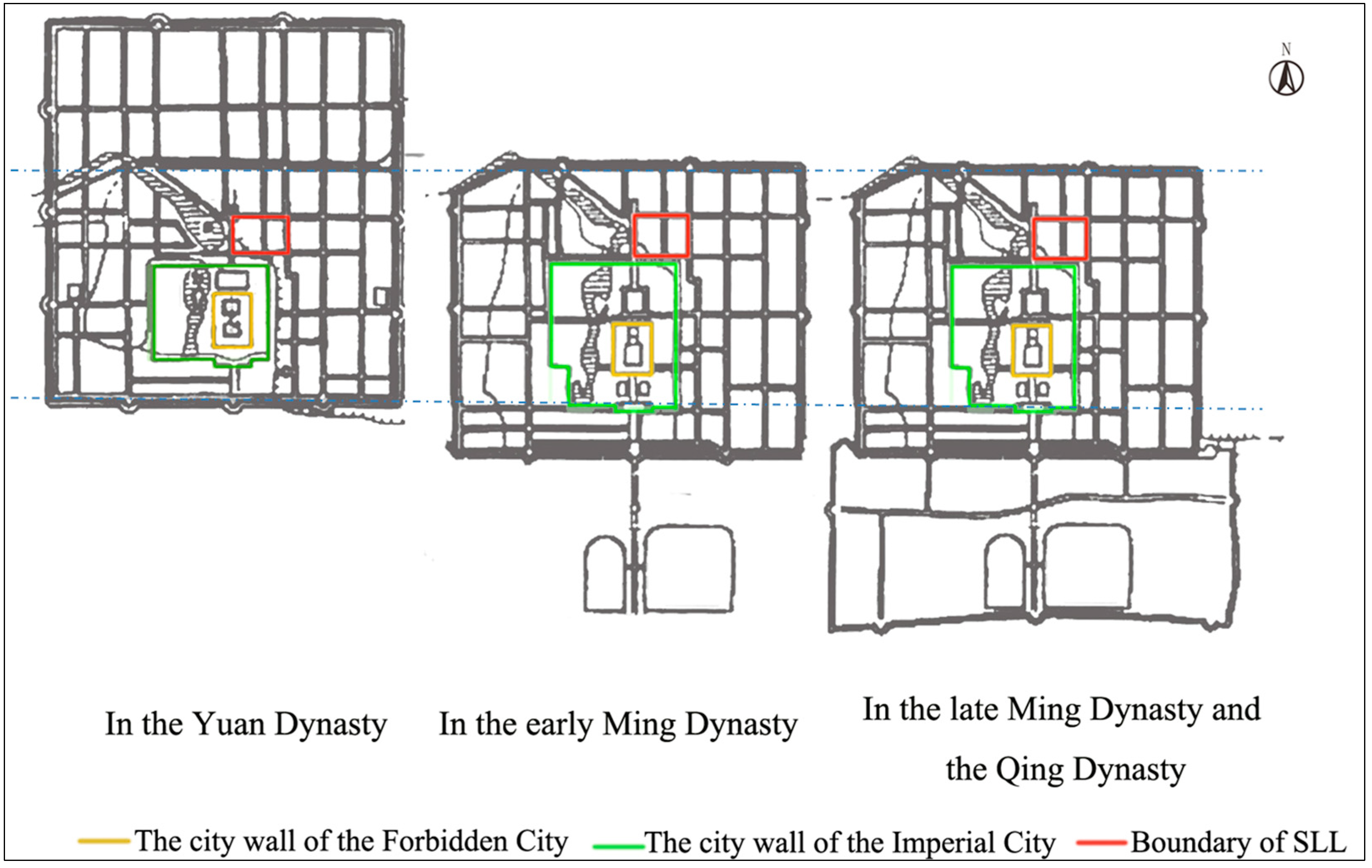

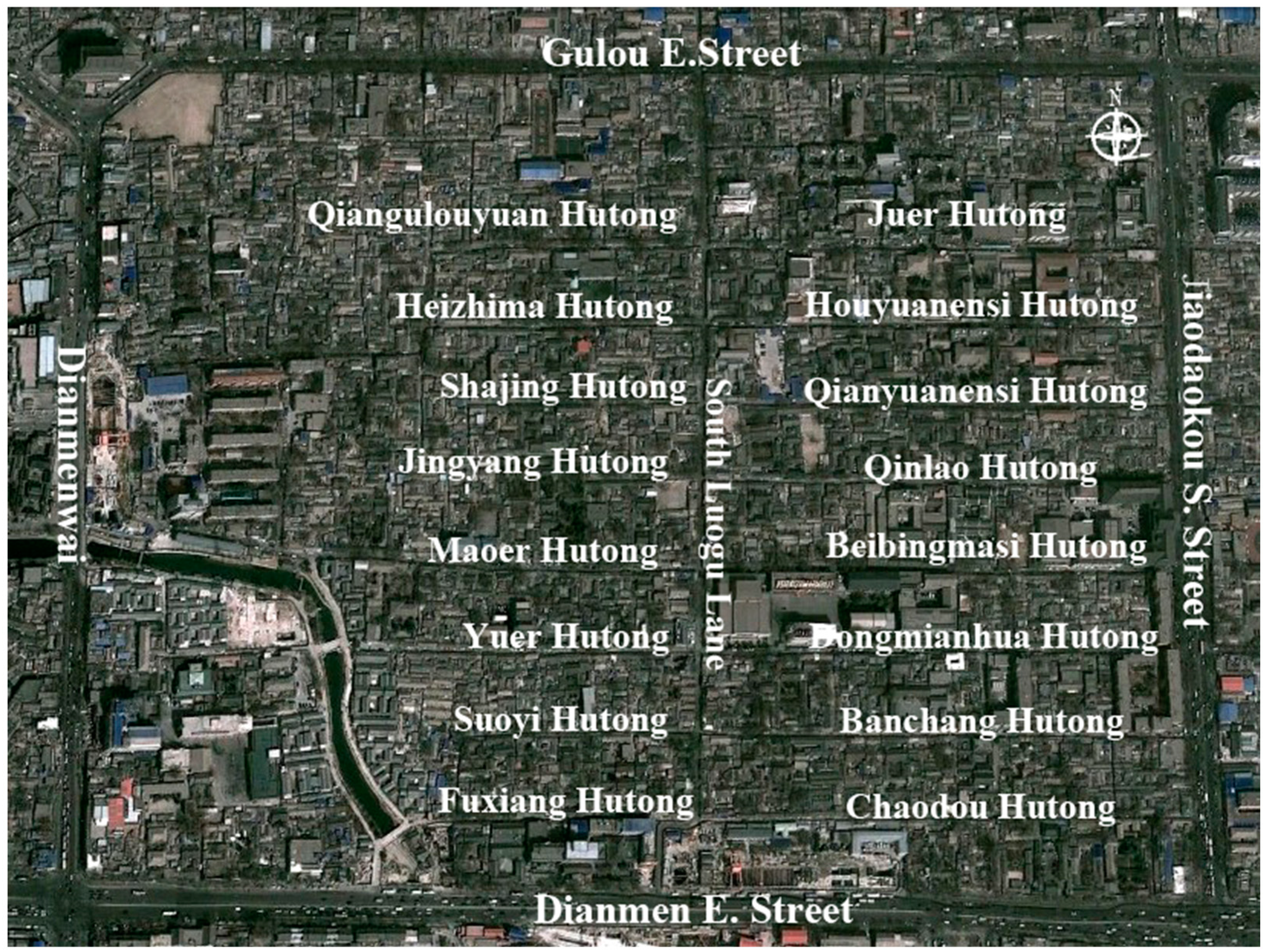

3. Beijing’s South Luogu Lane

4. From the Yuan Dynasty to the Mid-Qing Dynasty (before 1850)

4.1. Property Regimes and Capital Flows

4.2. Place Image: Residential Quarter for High-Ranking Officials

5. From the Late Qing Dynasty to 1949 (1851 to 1949)

5.1. Property Regimes and Capital Flows

| Address | The First Period | The Second Period | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing Ownership’s Elite and His/Her Identity | Investment | Housing Ownership’s Elite and His/Her Identity | Investment | ||||||

| No. 7, 9, 11, 13 in Mao’er Hutong | During the late Qing Dynasty: Wen Yu (a minister of the Interior) | Private investment for construction | |||||||

| 1917–1936: Guozhang Feng (The agency president of Beiyang government) | 1917–1936: Private investment for installing water apparatus and lamps | ||||||||

| 1937–1945: Lanfeng Zhang (A commander of puppet army) | 1937–1945: Private investment for renovation and redecoration | ||||||||

| No.35,37 in Mao’er Hutong | Rong Yuan (the father of the last queen) | Private investment for construction, The government invested heavily in renovation, repair | |||||||

| No.73,75,77 in Chaodou Hutong | Sengge Rinchen (a nobleman) | Private investment for expansion | Jiajin Zhu (A famous expert of cultural relics and the history) | Private investment for redecoration | |||||

| No.7 in Qiangulouyuan Hutong | Tu Qin Bao (a leader of yellow Bannermen) | Government investment for construction | 1911–1926:Zhaoxiang Wu (A famous merchants) | Private investment for renovation and redecoration | |||||

| 1927–1949:Shoushan Song (A senior general of Dongbei troops) | Private investment for renovation and repair | ||||||||

| No.59,65 in SLL | Chengchou Hong (a military commander at the beginning of the Qing Dynasty) | Wenzhong Pei (an archaeologist and, a paleontologist) | |||||||

| No. 13 in Heizhima Hutong | Kui Jun (a ministry of Justice, one of the four most wealthy) | ||||||||

| Mengyu Gu (A well-known politician) | Private investment for renovation and repair | ||||||||

| No. 7, 9 in Houyuanensi Hutong | Zai Fu (a descendant of the royalty) | Private investment for construction | |||||||

| No. 35 in Qinlao Hutong | Ming Shan (from the Ministry of the Interior) | Private investment for expansion, then divided and sold | |||||||

| No.15 in Dongmianhua Hutong | Feng Shan (a general) | Private investment for renovation | Unknown (divided and sold) | ||||||

| No.15,17,19 in Shajing Hutong | Kui Jun (from the Ministry of Justice, One of the four most wealthy) | Private investment for construction | |||||||

| No.17 in Beibingmasi Hutong | Ling Gui (from the Ministry of Personnel) | Erxi Zhao (a history museum curator) | Private investment for redecoration | ||||||

| No. 13 in Yu’er Hutong | Bushu Ye (the Emperor Huang Taiji’s fourth son) | Shuping Dong (the chairman of the Beihai Park Board) | Private investment for renovation and redecoration | ||||||

| No.3, 5 in Ju’er Hutong, No.6 in Shoubi Hutong | RongLu (from the Ministry of the Interior) | Private investment for construction | |||||||

| No.18 in Qinlao Hutong | 1940–1944:Duo Erjie (a nobleman) | ||||||||

| No.39 in Dongmianhua Hutong | Yunpeng Jin (the Acting Minister in the Republic of China) | Private investment for repair and renovation | |||||||

| No.57 in Beibingmasi Hutong | Longyou Xiao (One of t four very famous medical doctors) | Private investment for redecoration | |||||||

| No.11,15,17 in Fuxiang Hutong | Jinsheng Wang (a successful man in the gold business) | Private investment for construction | |||||||

| No.10,12 in Suoyi Hutong | Jinsheng Wang (a successful man in the gold business) | Private investment for construction | |||||||

| No. 2 in Qiangulouyuan Hutong | Ruqin Wang (a general) | ||||||||

| No. 1 in Houyuanensi Hutong | Lianying Li (a famous eunuch) | Private investment for construction | |||||||

| No. 45 on Dianmen east street | BaoQuan (a Sanyi minister) | ||||||||

| No. 7, 9, 11 in Shoubi Hutong | Liangqing Wei (a famous eunuch’s nephew in the Ming Dynasty) | ||||||||

5.2. Place Image: A High-Income Residential Area

6. A Fundamental Property Regime Revolution (1949 to 1978)

6.1. Property Regimes and Capital Flows

| Address | Elites | Time |

|---|---|---|

| No.31 in Yuer Hutong | Ronghuan Luo(A grand marshal) | After 1949 |

| No.33 in Yuer Hutong | Yu Su (A general) | After 1950 |

| No.13 in Yuer Hutong | Baishi Qi (A painter) | 1955–1956 |

| No.11 in Fuxiang Hutong | Shuchang Wang(A member of the CPPCC National Committee) | 1949–1960 |

| No.13 in Houyuanensi Hutong | Dun Mao (a famous writer) | 1974–1991 |

| No.2 in Suoyi Hutong | Ren Pu(The younger brother of the last Emperor of China) | After 1975 |

| No.84 on Di’anmen East Street | Youxun Wu(A physical scientist) | After 1949 |

6.2. Place Image: A Mixed-Income Residential Area

7. Property RegimeTransformationPost-1978

7.1. Property Regimes and Capital Flows

| Address | Elites | Ownership after 1978 | Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. 7, 9, 11, 13 in Maoer Hutong | Wen Yu, Guozhang Feng, Lanfeng Zhang | 7-Housing Administration Bureau (HAB) | 7-Tenement housing |

| 9,11,13-Government Offices Administration of the State Council (GOASC) | 9,11,13-Unoccupied | ||

| No. 35, 37 in Maoer Hutong | Rong yuan | Department | 37-Tenement housing |

| 35-Unoccupied | |||

| No. 73,75,77 in Chaodou Hutong | Sengge Rinchen, Jiajin Zhu | 73-department | Tenement housing |

| 75,77-GOASC | |||

| No.7 in Qiangulouyuan Hutong | Tuchyn Bao, Zhaoxiang Wu, Shoushan Song | GOASC | Commercial use |

| No. 59, 65 in SLL | Chengchou Hong, Wenzhong Pei | Private | Parts are tenements |

| Parts are for commercial use | |||

| No.13 in Heizhima Hutong | Kui Jun, Mengyu Gu | GOASC | Tenement Housing |

| No.7.9 in Houyuanensi Hutong | Zai Fu | GOASC | Unoccupied |

| No.35 in Qinlao Hutong | Ming Shan | GOASC | Single-familyhousing |

| No.15 in Dongmianhua Hutong | Feng Shan | HAB | Tenement housing |

| No.15,17,19 in Shajing Hutong | Kui Jun | HAB | Tenement housing |

| No. 17 in Beibinmasi Hutong | Ling Gui, Erxun Zhao | Private | Shops |

| No. 11,13,15 in Yu’er Hutong | Bushu Ye, Shuping Dong, Baishi Qi | Department | Museum |

| No. 3, 5, 7 in Ju’er Hutong, No. 6 in Shoubi Hutong | Rong Lu | 7-private | Dwelling |

| 3,5,6-GOASC | |||

| No. 39 in Dongmianhua Hutong | Yunpeng Jin | Department | Building for education |

| No.31 in Yu’er Hutong | Ronghuan Luo | GOASC | Single-family housing |

| No.33 in Yu’er Hutong | Yu Su | GOASC | Single-family housing |

| No.11 in Fuxiang Hutong | Shuchang Wang | HAB | Tenement housing |

| No.13 in Houyuanensi Hutong | Dun Mao | GOASC | Museum |

| No.7, 9, 11 in Shoubi Hutong | Liangqing Wei | GOASC | Tenement housing |

| No.18 in Qinlao Hutong | Duo Erji | Demolition | Demolition |

| No.57 in Beibingmasi Hutong | Longyou Xiao | HAB | Dwelling |

| No.84 on Di’anmenEast Street | Youxun Wu | HAB | Dwelling |

| No.2 in Qiangulouyuan Hutong | Ruqin Wang | Private | Single-family housing |

| No. 15, 17 in Fuxiang Hutong | Jinsheng Wang | 15-HAB | Tenement housing |

| 17-department | |||

| No.10,12 in Suoyi Hutong | Jinsheng Wang | HAB | 10 Single-family housing |

| 12 Tenement housing | |||

| No.1 in Houyuanensi Hutong | Lianying Li | Department | Tenement housing |

| No.45 on Di’anmen East Street | Bao Quan | Dwelling | |

| No.2 in Suoyi Hutong | Ren Pu | Private | Single-family housing |

| Year | Amount of Investment | Investment Direction | Specific Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 [54] | Environmental remediation | Ju’er Hutong’s remediation | |

| 1997 [55] | More than 8 million RMB (more than 1.3 million dollars) | Municipal project, style renovation | Constructing the sewage of SLL, renovating the courtyards protected areas |

| 1998 [56] | 2.03 million RMB (about 0.326 million dollars) | Environmental remediation | Remoulding 71 alley toilets |

| 0.185 million RMB (about 30000 dollars) | Environmental remediation | Buying garbage collector cars | |

| 1999 [57] | Municipal project | Remolding the sewers | |

| 2000 [58] | 0.66 million RMB (about 0.106 million dollars) | Municipal project | Remolding the sewers |

| 2001 [59] | Installing of anti-theft system | ||

| 2002 [60] | Style renovation | Improving the courtyard area environment | |

| 2003 [61] | Developing culture | Developing culture in Fuxiang Hutong | |

| 2005 [62] | 10 million RMB (about 1.6 million dollars) | Municipal project | Paving the way for SLL and laying pipes |

| 2006 [63] | 5.66 million RMB (about 0.909 million dollars) | Municipal project | Laying sewage pipeline and telecommunication lines, changing military communications line, laying the overhead lines into the ground, installing 4000 m security information transmission cable, laying 5000 square meters antique brick. |

| 3.1 million RMB (about 0.498 million dollars) | Style renovation | Painting 4500 square meters walls, repairing shops, demolishing 63 illegal buildings, repairing 120 doors, windows and 12 gates, clearing 120 unqualified boards, getting rid of 50 old awnings, pruning trees on both sides of the street, decorating parts of the bars and businesses | |

| Less than 2.5 million RMB (Less than 0.401 million dollars) | Style renovation | Renovating synthetically SLL, Ju’er Hutong, Qiangulouyuan HuTong, Qianyuanensi Hutong and Houyuanensi Hutong. Renovating the environment of Jingyang Hutong and Shajing Hutong | |

| 2007 [64] | Municipal project | Laying municipal engineering in 10 alleys and transformation project for coal to electricity | |

| 2008 [65] | Municipal project | Renovation barrier-free facilities in SLL | |

| 2009 [66] | Municipal project | Laying the overhead lines into the ground in Fuxiang Hutong, Suoyi Hutong, Jiangyang Hutong, Shajing Hutong, Heizhima Hutong and Qiangulouyuan Hutong. Removing 40 households, installing 4 box transformer substations and 1 opening and closing device. | |

| 2010 [67] | Developing tourism culture | Organizing series of folk cultural activities in SLL | |

| Style renovation | Removing the unqualified plaques and light boxes, repairing 400 square meters floor areas. | ||

| 200 million RMB (about 32 million dollars) [68] | Municipal project | Laying municipal engineering in the west of SLL, Putting 3800 m lines into the ground, removing 40 households, paving 5800 square meters roads. | |

| 25 million RMB (about 4 million dollars) | Commercial assistance | Subsidizing businesses | |

| 2011 [69] | Developing tourism, business culture | Holding the second SLL Drama Festival, improving management order |

7.2. Place Image: A Tourist District of Traditional Culture

8. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Power, A. Social Exclusion and Urban Sprawl: Is the rescue of cities possible? Reg. Stud. 2001, 35, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzu, G. Urban redevelopment, cultural heritage, poverty and redistribution: the case of Old Accra and Adawso House. Habitat Int. 2005, 29, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeoh, B.; Kong, L. The notion of place in the construction of history, nostalgia and heritage in Singapore. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 1997, 17, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. A Global Sense of Place. In Space, Place, and Gender; University of Minnesota Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1994; pp. 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The right to the city. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2003, 27, 939–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. For Space; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2005; pp. 50–150. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, L.; Massey, D. A woman’s place? In Geography Matters! A Reader; Massey, D., Allen, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984; pp. 128–147. [Google Scholar]

- Warde, A. Spatial change, politics and the division of labour. In Social Relations and Spatial Structures; Gregory, D., Urry, J., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1985; Volume 25, pp. 198–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, D. Areal differentiation and post-modern human geography. In Horizons in Human Geography; Gregory, D., Walford, R., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1989; pp. 67–96. [Google Scholar]

- Harver, D. Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 295–296. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; The University of Georgia Press: Athens, Greece, 2009; pp. 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Hope; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. Producing Places; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, P.; Kitchin, R.; Valentine, G. (Eds.) Key Thinkers on Space and Place; Sage: London, UK, 2004; p. 6.

- Pierce, J.; Martin, D.; Murphy, J. Relational Place-Making: the networked politics of place. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. New directions in space. In Social Relations and Spatial Structures; Gregory, D., Urry, J., Eds.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1985; Volume 25, pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Spatial Divisions of Labor: Social Structures and the Geography of Production; Methuen: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, M.; John, O. Defining Regions: the making of places in the New Zealand wine industry. Aust. Geogr. 2011, 42, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Place: A Short Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. Power-Geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place. In Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures Global Change; Bird, J., Curtis, B., Putnam, T., Tickner, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1993; pp. 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Zhang, E. The History of SLL; Beijing Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 2–180. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, M. Xi Jin Zhi Ji Yi, 2nd ed.; Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2001; p. 2. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lv, B. SLL in Jiaodaokou. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2007, 5, 139–142. [Google Scholar]

- China National Tourism Administration classifies tourist places into 5 levels. Each level has A and B grade

- Wang, L. Studies on China Urban Land Property Right; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 17–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Hu, J. The Housing Land Management in the East District in Beijing; Housing and Land Administration Bureau: Beijing, China, 1998; pp. 3–400. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J. Tian Zhi Ou Wen, 2nd ed.; Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1982; p. 85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- The “Eight Bannermen” System was Set up by the Emperor in Qing Dynasty for His Political Goal. It Provided the Basic Framework for the Manchu Military Organization. The Eight Bannermen Were Plain Yellow Bannermen, Bordered Yellow Bannermen, Plain White Bannermen, Bordered White Bannermen, Plain Red Bannermen, Bordered Red Bannermen, Plain Blue Bannermen, Bordered Blue Bannermen. Then, Based on people’s Culture and the Language (Not the Ancestry, Race or Blood), they were again Divided into Three Types of Main Bannermen, the Manchu Bannermen, Mongol Bannermen and Han Bannermen. The Bannermen had a Hierarchical Structure. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eight_Banners (accessed on 5 August 2014).

- Dang, J. The Advice about the Protection of Elites’ Former Houses in SLL. Available online: http://www.bj93.gov.cn/czyz/jyxc/t20130917_215917.htm (accessed on 17 September 2013). (In Chinese)

- Yu, M. Ri Xia Jiu Wen Kao, 2nd ed.; Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2001; p. 578. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C. Chen Yuan Shi Lue, 2nd ed.; Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2001; p. 109. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Jing Shi Fang Xiang Zhi Gao, 2nd ed.; Beijing Ancient Books Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2001; p. 81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. Xiao Ting Za Lu; Zhong Hua Press: Beijing, China, 1980; p. 510. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dang, J. The historical and cultural relics in SLL. Beijing Arch. 2011, 5, 52–53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Q. Wen Yu’s garden. Trad. Chin. Archit. Gard. 2000, 1, 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. SLL. Econ. Trade Update 2011, 8, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Beijing Municipal Government, China. The Letter and List, Draw Money Duplicate, etc. from the No. 4 Municipal Administration in Beijing and They Were the Approval of Repairing the Road, the Gap with Lid from Mianhua Hutong to the South of SLL; Beijing Archives Administration: Beijing, China, 1919; J017-001-00109. (In Chinese)

- Massey, D. Places and Their Pasts. Hist. Workshop J. 1995, 39, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Spatial Divisions of Labor: Social Structures and the Geography of Production, 2nd ed.; The Macmillan Press Ltd.: Hampshire, UK, 1995; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, J. Conservation Planning of 25 Historic Areas in Beijing Old City; Beijing Yanshan Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 155–168. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q. The confusion and digestion of the urban land under the background of “All belong to the country”. China Leg. Sci. 2012, 3, 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J. The 60 years of land system reform in new China: A review and prospect. China Nat. Cond. Strength. 2009, 9, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Jin, X. Thirty Years of Land System Reform in China; The Science Press: Beijing, China, 2009; pp. 10–78. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Urban land reform in China. Land Use Policy 1997, 14, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, S. The retrospect and prospect of Chinese city land use system reform in 60 years. Rev. Econ. Res. 2009, 63, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. The historical changes and countermeasures of Chinese urban housing system. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2007, 3, 134–136. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. Qinlao Hutong (2): Qinlao Hutong in SLL. Available online: http://blog.sina.com.cn/u/1253711215 (accessed on 26 September 2012). (In Chinese)

- The Editorial Department of Beijing Volume. Books of Contemporary Chinese City Development; Contemporary China Press: Beijing, China, 2011; pp. 46–60. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Research on the Reform of the Land System in The Process of Urbanization; Hebei People’s Press: Shijiazhuang, China, 2013; pp. 143–151. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W. The Research on Efficiency and Justice Land System Reform of China. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Geosciences, Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. The changes of land system in China and its problems. Friends Farmers Get Rich. 2011, 13, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J. The reform and development of Beijing land use system in the 60 years after the new Chinese founded. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2009, 6, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X. Research of the Case of Transformation and Renewal of the South Lane Area in Beijing. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Civil Engineering and Architecture, Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—1996; The Olympic Press: Beijing, China, 1997; pp. 245–247. (In Chinese)

- Liu, X. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—1997; The Olympic Press: Beijing, China, 1998; pp. 277–279. (In Chinese)

- Liu, X. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—1998; The Olympic Press: Beijing, China, 1999; pp. 264–265. (In Chinese)

- Liu, X. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—1999; The Olympic Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 320–323. (In Chinese)

- Chen, P. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2000; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 298–300. (In Chinese)

- Chen, P. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2001; Tongxin Press: Beijing, China, 2002; pp. 314–317. (In Chinese)

- Lu, Y. (Ed.) Beijing East. District Yearbook—2003; National Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2003; pp. 312–315. (In Chinese)

- Lu, Y. (Ed.) Beijing East. District Yearbook—2004; National Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004; pp. 315–318. (In Chinese)

- Lu, Y. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2006; Local Records Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 297–300. (In Chinese)

- Yang, Y. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2007; Local Records Press: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 319–323. (In Chinese)

- Yang, Y. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2008; Local Records Press: Beijing, China, 2008; pp. 284–288. (In Chinese)

- Yang, Y. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2009; Local Records Press: Beijing, China, 2009; pp. 361–366. (In Chinese)

- Niu, Q. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2010; The Central Literature Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 328–334. (In Chinese)

- Niu, Q. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2011; Zhong Hua Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 339–340. (In Chinese)

- Zhang, R. This Characteristics Street SLL’s Expansion This Year. Jinghua Times 2010, 7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Q. (Ed.) Beijing East District Yearbook—2012; Zhong Hua Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 305–306. (In Chinese)

- Huang, B.; Dai, L.; Hu, Y.; Lv, B. A study on the influence mechanism of cultural and creative industries in the old city regeneration from the space production perspective—Taking SLL as a case. Beijing Plan. Rev. 2012, 3, 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, E. Old Cities, New Assets: Preserving Latin America’s Urban Heritage; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Min, Z. Yard Deep Memories of Ancient Culture. Beijing Daily, 23 March 2012; 12. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, M. Poor Families in Beijing can Apply Fund from Local Government for House Repair. Available online: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2014-06/11/c_1111079550.htm (accessed on 11 June 2014). (In Chinese)

- Adams, P.C.; Hoelscher, S.D.; Till, K.E. (Eds.) Textures of Place: Exploring Humanist Geographies; University of Minnesota Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2001; p. xxxi.

- Jamal, T.; Stronza, A. Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P. Global trends affecting tourism in protected areas. In Tourism in Protected Areas: Benefits beyond Boundaries; Bushell, R., Eagles, P., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Z.; Zhou, S.; Young, S. Place, Capital Flows and Property Regimes: The Elites’ Former Houses in Beijing’s South Luogu Lane. Sustainability 2015, 7, 398-421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7010398

Cheng Z, Zhou S, Young S. Place, Capital Flows and Property Regimes: The Elites’ Former Houses in Beijing’s South Luogu Lane. Sustainability. 2015; 7(1):398-421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7010398

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Zhifen, Shangyi Zhou, and Stephen Young. 2015. "Place, Capital Flows and Property Regimes: The Elites’ Former Houses in Beijing’s South Luogu Lane" Sustainability 7, no. 1: 398-421. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7010398