1. Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) recognizes that corporate growth and profitability are important, but it also requires a firm to pursue societal goals such as environmental protection, social justice and equity [

1,

2,

3]. In theory, CSR includes four aspects; the first aspect considers corporations as only an instrument for wealth creation, another aspect regard CSR as the responsible use of a corporation’s power in society, the third aspect sees CSR as a way of corporations to satisfy social demand, and the fourth aspect believes CSR as the ethical responsibility of corporations to society [

4]. In practice, socially responsible corporation should including four faces: economic face, legal face, ethical face and philanthropic face, that is to be profitable, to obey the law, to engage in ethical behavior, and to give back through philanthropy [

5]. As such CSR begins to impinge upon issues that are traditionally the domain of politicians and impacts upon their relationships with the local communities that they seek to serve [

6,

7].

Different approaches have been proposed to make corporations ethical and socially responsible. Goodpaster’s [

8] Type 3 thinking, Freeman’s [

9] stakeholder theory and Boatright’s [

10] Moral Manager Model stated that the focus of business ethics should be on individual responsibilities of managers. However, Boatright in the same paper disagreed with the Moral Manager Model and proposed a Moral Market Model that argued business ethics should be based on the regulation of economic markets and on the shape and design of institutions that regulate business from the outside. In line with Boatright, Homann [

11] argued that incentives are action-determining expectations of advantage, even morality must somehow be based on expectations of advantage; otherwise it cannot be put into practice in everyday life. On the contrary, Hendry [

12], agreed with the Moral Manager Model, and insisted that with a combination of rapid economic development and moral uncertainty during the current commercial and cultural globalization, “the need for moral managers has never been greater”. However, Smith [

13] reasoned that the Moral Market Model and Moral Manager Model are compatible frameworks for corporate social responsibility.

Despite the debate between Hendry and Boatright about moral markets and moral managers, Hofstede [

14] noticed that cultural differences could cause different understanding of the role and expectations of society in driving CSR. Many of these systems of ethics are embodied in cultural traditions that are, in origin, older than those of western capitalism. Hofstede [

14] discovered four fundamental dimensions that inform cultural differences between nations: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity. Based on his own theory, Hofstede found a great disparity in the level of collectivism between Arab or Muslim countries and Western nations, such as the UK.

CSR has increasingly been seen as important in China, yet the evolution of CSR in China has been different from what has been seeing in the West. There are ironies and this paper seeks to explore some of these. China’s economy has grown remarkably since its adoption of market-oriented reforms. According to the World Bank [

15], China’s GDP grew at an average annual rate of 10% between 1980 and 2012. Although some argue that China is a phenomenally successful economy that will continue to grow [

16], the uneven development in political and cultural spheres has caused many concerns within the country. The traditional “public” companies, claiming the demands of the free market, have cancelled their social welfare programs, such as emphases on long-term and stable employment, company provided education and health facilities. Some of these social divestments were made through outsourcing, which offset their effects, at least partially, but, overall, the resulting decline in CSR implemented by such companies that have a significant presence in China and the increasing inequality caused by growth have exacerbated inequalities between urban and rural areas, between the coastal and the inland regions, and between the new entrepreneurs and the rest of the population. Moreover, millions of urban immigrant workers labor under poor occupational health and safety (OHS) conditions and large numbers of urban residents have been laid off from SOEs and remain unemployed and impoverished. Product safety has been downgraded by profit driven producers [

17]. In addition, China has one of the worst pollution problems on the planet: in fact it has overtaken the US as the biggest carbon dioxide emitter since June 2007 [

18,

19]. The prolonged, widespread smog that blanketed many Chinese cities in 2013 has not only caused serious harm to public health, but also resulted in massive economic losses in many other ways [

19,

20].

Given the importance of CSR in China and the rest of the world, various scholars tried to identify the factors that affect CSR. As early as 1976, Fry and Hock [

21] found an interesting relationship between firm size and social responsiveness of US corporations: the bigger the company, the more space in its annual report is allocated to social responsibility activities. The same conclusion was reached by Fombrun and Shanley [

22], Pava and Krausz [

23] regarding the US companies, and Moore [

24] regarding the UK companies. Shafer

et al. [

25] compared the perception of MBA students to CSR in the US and China and found that while US managers held positive and proactive views toward CSR, Chinese managers are contradictory in their views of what is more important—profit or CSR and corporate ethics. A few Chinese scholars, by investigating the Chinese food industry, found that company size is an influencing factor in whether a company would adopt CSR policy, but their results are inconsistent, some regard big companies more CSR sensitive while others consider the opposite [

26,

27,

28].

This paper aims to answer the following two questions; how has CSR been affected by economic changes in China during the transitional period? What are the cultural and political reasons for this? This paper presents the results of a case study of a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) and a group of small private firms in the same industrial sector in Zhengzhou City, Henan Province over the time span of eight years.

2. CSR in China

Although it is widely accepted that the roots of CSR go back to the 1960s and 1970s, when the environment was emerging as a worldwide concern by the western world, the history of CSR in China goes back a long way. Some Chinese scholars believe that the underlying concepts of CSR can be seen as early as 2500 years ago in the era of the Spring and Autumn [

29]. The concept of CSR, in the Chinese context, has much to do with the Confucian virtue of

Yi, which means righteousness: using the principles or norms of obtaining and distributing benefits [

30]. Opposite to

Yi is

Li, which means the benefits and profits themselves. The relationship between

Yi and

Li can best be described by the Confucian view that a person of noble character understands

Yi, while a lower person only knows

Li. A businessman with

Li character just pursues short-term profit and self-interest, while a

Yi businessman considers longer-term and broader gains. So in this respect, this Chinese ancient philosophy of CSR (

Yi rather than

Li) can be interpreted as being ethical, rather than simply profit-oriented, and a value that is reflected in the western CSR theory. However, there is a crucial difference because in the Chinese context,

Yi requires not only acting and behaving in the right way but also following the given social hierarchy; for example the son obeys the father, the wife obeys the husband, the younger brother obeys the elder brother, and the inferior obeys the superior.

In practice, CSR in China has always been the “

ideological and political work” of the administrative departments [

26,

31]. The Chinese government has frequently used awareness campaigns to promote corporate social responsibility, for example, by holding meetings and displaying slogans such as “

serve the people” and “

socialist spiritual civilization”. “

Harmonious society” is a slogan that was introduced in 2004 at the Fourth Plenum of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), 16th plenary meeting. The most recent slogan was “

China dream” promoted by the new CCP General Secretary Jinping Xi in 2013, which is about Chinese prosperity, collective effort, socialism and national glory [

32].

The evolution of CSR in modern China is linked to economic reform and can be divided into two periods:

- (1)

The socialist planned-economy period (1950–1978)

- (2)

The transitional period (after 1978) when China launched its transformation from a socialist planned economy to a socialist market economy.

However, as China’s economic reform did not officially target marketization before 1992 when the 14th Congress of CCP was held, the second period can also be divided into two: 1978 to 1992 and 1993 to the present.

In the planned economy, the notion of sustainability had an important place. In 1955, Chairman Mao Zedong called for green policies because they would benefit agriculture, industry, and other aspects of society [

33]. Equality and social justice were also among China’s objectives during the Mao era [

34]. The slogan “

serve the people” introduced by Mao when the People’s Republic of China was first established, called for state organizations to be socially responsible. As the representatives of the state, the state-owned enterprises (SOE) were to serve the people from cradle to grave, employing people for life and providing employees and their families with comprehensive welfare, such as free accommodation, education, medical services, cheap food and so on. Workers’ rights were central, and during this period, CSR in both urban and rural areas was very high (in rural areas, peasants were well looked after by their communes) [

17]. During this period, CSR was strongly politicized due to the socialist nature of the enterprises, obeying state orders and serving the employees were central concerns for socialist enterprises. CSR at that time was a political responsibility.

Before the economic reform began to affect SOEs around 1984, CSR followed the same pattern as the planned economy period [

35]. From 1985 to 1992, the government tried various measures to reform the SOEs without eliminating state ownership, but these reforms failed. According to the 1999

China Statistical Yearbook, 17,000 schools in China in 1998 (30% of the total) were run by SOEs. These schools taught more than seven million students and employed 626,000 staff. Apart from investment in school infrastructure, SOEs spent 6.4 billion Yuan ($773 million) annually to keep the schools running. In the same year, one-third of the medical services in China (approximately ninety-one-thousand institutions) were also run by SOEs, and the total yearly expenditure was 3.1 billion Yuan ($37 million).

Learning from previous experiences, the 14th CCP plenary meeting in 1992 called for ownership reform. The state started to downsize and withdraw from direct economic management. Private firms were allowed to exist and grow, and SOEs were permitted to pursue their own interests. Profitability became the primary goal of firms. A survey of 210 SOEs in China reported on corporate objectives [

36]. Of these, 45.7% chose high profits as their first objective, 24.7% chose growth, and 9.8% chose increasing market share, while only 2.6% regarded increasing employees’ income as their first objective.

Changes in the role of the state and to the objectives of the firms have resulted in large changes in CSR. The most significant of these was the elimination of the cradle-to-grave welfare provision enjoyed by workers in SOEs. Health and education services largely shifted from a state-payer to a user-payer principle, and this resulted in inequality of access. Indeed, in many remote rural areas, people cannot afford medical services or education. In 1997, following the state policy of “

invigorating large firms while relaxing control over the small ones” (

zhuda fangxiao), many small SOEs went bankrupt. According to the 2001

China Statistical Yearbook, from 1998 to 2000, 21.4 million people were laid off by SOEs. These workers became the new urban poor who struggled to find jobs in the increasingly market-oriented environment, and this caused widespread social unrest. Labor protests have increased sharply in frequency and severity. The state has been attempting to address these issues through a variety of social security programs, but this effort has only partly alleviated the situation due to the limited access to and the misuse of the social security fund, attributed to inadequate laws, lack of transparency, and inadequate public supervision [

37].

A low level of CSR has also been reflected in worsening labor standards in China. A report on child labor in Chinese firms that produced licensed goods for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games helped bring China’s poor labor practices into the spotlight. It was reported that children as young as twelve were hired to produce Olympic merchandise by firms in China’s Guangdong Province. Undercover researchers working in the firms reported that adult workers were paid half the legal minimum wage, and that children doing the same jobs were paid even less. Both children and adults worked up to fifteen hours a day, seven days a week. It was also reported that workers were instructed to lie to inspectors about their wages, health, and safety conditions, and that anyone who told the truth was fired [

38]. Researchers have uncovered poor labor practices at many Chinese suppliers to international corporations, and even Apple Corporation has admitted that some of its Chinese suppliers use child labor [

39]. At Foxconn, one of Apple’s long-term contractors, high stress and long working hours contributed to the suicides of thirteen workers [

40]. According to the

Nike Corporate Social Responsibility Report FY 07 08 09, more than 20% of Nike’s original equipment manufacturers have asked their employees to work sixty hours or more per week [

41]. The National Labor Committee (NLC) in the United States claimed that Dongguan Kunying Computer Goods Company, a Chinese supplier for Microsoft, employed hundreds of child laborers and asked them to work long hours; one worker was found to work a thirty-four-hour shift at the pay rate of sixty-five cents per hour. According to the NLC, Dongguan Kunying forbids its workers to talk to each other, to listen to music, or even to use the toilet during working hours. A management consulting company listed seventeen poor labor practices on their website, including child labor, illegal restriction of personal freedom by taking workers’ ID documents, enforced overtime, low wages, bad accommodation, and poor workplace health and safety conditions [

42]. Some Chinese companies continue to use toxic substances without adequate safety measures. Cadmium, for example, is strictly regulated in Western countries but still widely used in China [

43].

Chinese labor laws give workers the right to form unions, and by law all companies that have more than one hundred employees are required to have unions, but it is estimated that only a little over 60% of companies in China have such unions [

44]. Even those unions that do exist are arms of the state controlled by the CCP. The unions do not negotiate contracts and do little in the way of the traditional union activities seen in Western countries, such as lobbying for better wages and better working conditions.

From an environmental perspective, China’s high economic growth rate in recent years has been at the expense of massive energy consumption and extensive resource and capital investment. China is the world’s second largest energy consumer after the United States [

19,

45]. In 1980, China consumed approximately 1.8 million barrels of oil per day, and this rose to approximately 6.4 million barrels per day in 2004—an increase of more than 250%. In aggregate terms, China is the world’s number-one emitter of carbon dioxide (CO

2), one of the most abundant greenhouse gases, so China’s environmental issues are not just a domestic concern [

46]. While some progress in improving energy efficiency and reducing CO

2 emissions has been made, 75% of China’s energy production is still dependent on coal. Meanwhile, demand for automobiles is growing quickly, and respiratory illness and heart disease related to air pollution are the leading causes of death in China. According to the China National Environment Monitoring Council, there were more than 20 days in January 2013 when air quality was below the standard in Beijing. Nair

et al. [

47] estimated that outdoor air pollution contributed to 1.2 million premature deaths in China in 2010, nearly 40% of the global total. To mitigate environmental degradation, the Chinese state has put in place several environmental laws and policies, but because of a lack of enforcement, these actions have not improved the situation significantly [

19].

The remainder of this paper will explore these changes at a more local-scale, by focusing on one SOE company and some of the newer companies that have emerged to compete with it.

3. Charting the Changes in CSR in China: A Case Study

A company referred to here as ZZAC was selected as the basis for the case study because it is “representative” of many of the large SOEs in China. It was also accessible because one of the authors once worked in the company for a number of years. This was crucial because some of the information being collected could be viewed as sensitive, and for cultural reason Chinese people are hardly open to strangers, even when the topic is not sensitive, hence it was necessary for people to feel that the researcher was somebody they knew and was trustworthy. As the first abrasives firm in China, and indeed the biggest of its kind in Asia, ZZAC was established in the 1950s in Zhengzhou City in central China with support from the central government in both financial and human resources. It grew continuously before the SOE reform in 1984 and managed to maintain this momentum in the first few years of the reform. It benefited from the state’s reform policy

i.e., “

zhuada fangxiao”, and became a publicly listed company in 1993. At its peak in 1997, ZZAC employed 9549 individuals. Its output reached a peak of 463 million Yuan in 2000. However, despite this increase in output until 2000, total profit (pre-tax profit) has fallen since 1994, and so has the employment level (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The change of gross value of industrial output, total profit and employment of ZZAC (1966–2010).

Figure 1.

The change of gross value of industrial output, total profit and employment of ZZAC (1966–2010).

Like all other SOEs in China, ZZAC, under the planned economy, was an “iron-rice-bowl” to its employees. Apart from providing a job for life, it also provided cradle-to-grave services for its employees and their families, including nursery, primary and middle school education to employees’ children, professional training to employees in service and future employees (many of them were children of current employees of ZZAC), housing facilities, cafeteria, hospital, community recreation facilities, etc. But, the market reform of the SOEs in China increased competitiveness in the sector, leading to a change in the objectives of firms like ZZAC from facilitating full employment and social stability to increasing economic efficiency.

In addition to increasing competition in the large SOE sector, the market reforms in China also created a dynamic, privately owned small firm sector. Any “case study” based analysis of CSR, therefore, has to consider what was happening, not only within large firms but also within the increasingly important small firm sector that began to exist side-by-side with the large firms. In 2009, medium and small enterprises accounted for 99% of China’s total number of enterprises, which helped greatly with the employment. 60% of patents, 70% of the technological innovation, and 80% of new products were developed by medium and small enterprises [

48]. To study this, we selected four small private factories (PAFs;

Table 1) operating within the same industrial sector as ZZAC. These firms produced various types of abrasive and grinding products that have equivalents within ZZAC’s product range. The owners of the PAFs are previous ZZAC employees. As with the multitude of similar factories in China, the PAFs have been the driving force of China’s growth over the last two decades. However, they have received less support from the government and banks than the SOEs and many of these small private sector firms struggle to obtain adequate finance. Accessibility was also the reason that these four PAFs were chosen for the study.

Table 1.

Summary of the four private abrasive factories (FAFs) included in the research.

Table 1.

Summary of the four private abrasive factories (FAFs) included in the research.

| Code | Year of Establishment | Number of Employees | Manager’s Educational Level | Origin of the Managers | Main Products |

|---|

| 2005 | 2010 |

|---|

| PAF1 | 1991 | 25 | 25 | Primary school | Retired ZZAC employees | Small cutting wheels |

| PAF2 | 2000 | 15 | 15 | Middle school | Redundant former ZZAC employees | Special shaped grindings |

| PAF3 | 2003 | 35 | 60 | University | Redundant former ZZAC employees | Grinding materials |

| PAF4 | 2000 | 12 | 120 | Masters | Resigned former ZZAC employees | Replicas of imported grindings |

The fieldwork was undertaken in Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, China, and was carried out in three phases between 2004 and 2011. Data collection in the first phase spanned 2004 and 2005 and comprised a questionnaire survey, face-to-face interviews, observations and telephone interviews, and was aimed at exploring CSR of the case companies from economic, social and environmental dimensions. The second phase was undertaken in 2006, and was designed to fill in gaps identified after the first phase. Data collection in the second phase comprised face-to-face and telephone interviews with key informants along with the collection of new secondary data that was not available during the first phase. The third phase took place in 2011, and was designed to extend the analysis to the present. Data collection involved face-to-face and telephone interviews with key informants.

Table 2 lists the different stakeholders of ZZAC and the small factories PAF1, PAF2, PAF3 and PAF4 included in the research. The stakeholders included current employees, former employees (including both the redundant former employees and retired employees) of ZZAC as well as farmers of the communities around ZZAC, and PAF employees and farmers of the communities that PAFs are in. while the current employees were able to provide their perspectives of current conditions within their companies, as well as the benefits and costs of working within there, it was assumed that they would be influenced by being economically dependent on the company. Hence, it was decided to also interview employees who had been laid off or had retired from ZZAC. These groups would have first-hand experience of the company but would no longer be economically dependent upon it. The phenomenon of redundancies is actually one of the important social and economic impacts that ZZAC has had, and retired employees can provide information about the past periods of ZZAC. In addition, 22 senior managers of ZZAC were questioned regarding their perceptions of the company’s environmental impact and its future. It is assumed that senior managers as a separate group might have different views because of their position within the firm. Finally, to seek opinions from different perspectives, a sample of farmers living and farming near ZZAC, local shopkeepers and relevant government officers were also questioned. Sampling of ZZAC current employees covered all divisions of the firm, while sampling of former employees was based on residential area and accessibility. A total of 167 semi-structured questionnaires (95%) issued to ZZAC current employees, redundant former employees and five senior managers were completed and returned. The questionnaire comprised a mix of closed and open-ended questions, and aimed to cover the economic, social and environmental impacts of the firms. To gain more insight, 17 additional senior managers of ZZAC were questioned face to face. A small sample (23) of farmers living and farming in communities near ZZAC, local shopkeepers (one) and relevant government officers (seven) were also interviewed. Because of the simpler management structure of private firms in our case and more difficult access to the local communities, only the managers and current employees of these firms were questioned and a small number of farmers near PAF1 were interviewed. A total of 104 face-to-face interviews were conducted with these stakeholders for ZZAC and the PAFs.

Table 2.

Summary of the survey and interviews undertaken.

Table 2.

Summary of the survey and interviews undertaken.

| Category of Respondent | Sample Size | Questionnaire Survey | Number of Face to Face Interviews |

|---|

| Responses | Response Rate (%) |

|---|

| ZZAC Current employees | 123 | 116 | 94 | |

| ZZAC redundant former employees | 53 | 46 | 96 | 5 |

| ZZAC senior manager | 22 | 5 | 100 | 17 |

| ZZAC retired employees | 5 | | | 5 |

| Farmers living near to ZZAC | 23 | | | 23 |

| Farmers living near to PAFs | 7 | | | 7 |

| PAFs employees | 39 | | | 39 |

| Government | 7 | | | 7 |

| Shop keepers | 1 | | | 1 |

| Totals | 280 | 167 | 95% | 104 |

4. Results

4.1. A Retreat from CSR

ZZAC set up a series of welfare facilities following its establishment in 1956, including a number of schools, a hospital, kindergarten, leisure facilities, and cafeterias to serve ZZAC employees and their family members. In addition, a milk station to supply milk to ZZAC employees and their families was set up because the milk supply at that time was not sufficient in China. It closed in the early 1990s when milk supplies improved. As a result, ZZAC became a typical “

big and complete” enterprise in the local parlance. Its medical and educational facilities provided opportunities and convenience to many within the local community, and the cafeteria, leisure facilities and milk station had helped to improve the quality of life for ZZAC people. However, since 1993, in line with the national policy of decreasing the burden of large and medium enterprises in China, ZZAC started to cut away its excessive vertically integrated ties so as to increase its specialization. All the non-profit units, including the hospital, cafeteria, schools and retirement benefit office, along with more than 1100 current employees, have been separated from ZZAC and have gradually become independent profit centers, namely the ZZAC Industry Company. ZZAC was still in charge of the ZZAC Industry Company after the separation and to some extent, the ZZAC Industry Company still relied on ZZAC financially. The agreement of Debt Equity Conversion in 2000 finally brought this separation into effect. The primary and middle school were handed over to the state in 2004 and 2000, respectively, and ZZAC stopped financing the hospital and kindergarten and other welfare facilities during this period. As a result, free education is no longer available, nor is subsidized medical treatment for employees. These were initially replaced by discounts for some hospital treatments but these discounts stopped completely in 2006. After losing financial support, ZZAC hospital, kindergarten and other welfare facilities deteriorated, which have affected people’s perceptions of these facilities and their choice to use them. The divestment process lasted for over 10 years:

1993—ZZAC became a listed company. ZZAC Industry Company was established and separated from ZZAC, which included ZZAC schools, hospital, kindergarten, entertainment facilities, and other affiliated units. But this separation was just in name. The state entrusted ZZAC Industry Company to the care of ZZAC.

2000—ZZAC middle school was handed over to the state by ZZAC Industry Company.

2004—ZZAC hospital charge to ZZAC employees from zero to 30% discount.

Funding for staff to look after the entertainment facilities was stopped.

ZZAC primary school was taken over by the state.

2006—ZZAC hospital started to apply full charges for ZZAC employees.

Before long, the impact of decreased investment in these facilities began to be seen in terms of a decline in the use of their services making them less attractive and therefore less viable. In what follows, we will consider this process in some detail in the context of three of the facilities provided—health, education and social welfare.

There are no personal doctors in China and when people are ill they can choose to go to any hospital they wish and, of course, can afford. During the survey in 2004–2005, the current and former employees were asked how they thought the ZZAC hospital was performing in general terms, compared with other hospitals in the area (see

Table 3). Few respondents thought that the ZZAC hospital was better than others, while 65% of former employees and 75.2% of current employees said that ZZAC hospital was worse than others. In the past the ZZAC hospital was the main hospital for the majority of ZZAC employees and their families. In the survey, current and former employees and their family members were asked if they would like to go to ZZAC hospital when they were not well. Only 30% of former employees and 20% of their family members would choose to go to ZZAC hospital, and the proportion of current employees and their family members who choose ZZAC hospital is 28% and 22.4%, respectively. Interviews with farmers in the villages around ZZAC, Luoda Temple and Shiyang Temple shows that only two out of 23 (8.7%) interviewees would choose to go to ZZAC hospital if they did not feel well. The reasons most people would not choose ZZAC hospital is that firstly, ZZAC hospital does not provide as good service as other hospitals do, and secondly, ZZAC hospital is overpriced for its services.

As part of the withdrawal of ZZAC’s social CSR, the ZZAC kindergarten has also become independent from ZZAC. The secretary of the ZZAC kindergarten said that before 2000, the kindergarten was only open for ZZAC employees’ children and it was free of charge, but it has changed in recent years. They are now open to the public and charge the market price for all children. In the survey, it was found that about 62% of current employees would like their children to go to ZZAC kindergarten, while the rest of chose to use other local kindergartens. However, less than half of former employees (48.7%) would choose to send their children to the ZZAC kindergarten. The reason for their choice of the ZZAC kindergarten is mainly that it is close to work/home, hence it is convenient to drop off and pick up children.

Table 3.

Interviewees’ perceptions of and preference to ZZAC hospital relative to other hospitals around at the time of survey (2004/2005).

Table 3.

Interviewees’ perceptions of and preference to ZZAC hospital relative to other hospitals around at the time of survey (2004/2005).

| | ZZAC is Better | ZZAC is Worse | Same | Total |

|---|

| Perception | Current employees | 2 (1.9%) | 79 (75.2%) | 24 (22.9%) | 105 (100%) |

| Former employees | 0 (0%) | 26 (65%) | 14 (35%) | 40 (100%) |

| Preference | Percentage of interviewees who choose ZZAC hospital when they get sick? |

| Current employees | 28% |

| Current employees’ family | 22.4% |

| Former employees | 30% |

| Former employees family | 20% |

| Farmers living nearby | 8.7% |

| Reasons that ZZAC hospital is not preferred | 1. ZZAC does not provide as good service,

2. ZZAC hospital is over priced for its service. |

There had been two libraries in ZZAC, a reference library storing technical books and another ordinary library storing other books including a fiction section and magazines. At the time of writing, the reference library was closed and the ordinary library was open just three days a week. Not many people come to borrow books as there have been few new books or magazines acquired in recent years. Only 12% of survey respondents said that they used the library while 52% said they used to visit the library in the past but have since stopped.

Where ZZAC and its community are currently situated was once outside of Zhengzhou City in the undeveloped rural land. There was limited road access prior to ZZAC. The existence of ZZAC resulted in a number of roads being built in the area. Yihe Road was built during the establishment of ZZAC in the 1950s to connect the company site and the employees’ living area (which later became the ZZAC community). Because of this special purpose, it was called “ZZAC Road” by local people. Another road (Huashan Road) was set up later to facilitate ZZAC’s transport of products and materials by large road vehicles. Along with the expansion of ZZAC community, a larger and more complex road network and a sophisticated public transport system were developed connecting the ZZAC area and the rest of the city. In 2010, and there were around 10 bus routes stopping in the ZZAC area. During the survey, about 86% of current employees agreed that the roads and public transport were better because of ZZAC’s presence, and 87% admitted that the improved road and public transport system had made life easier for them. ZZAC has also been responsible for the road maintenance in its area, and for this purpose a new office named “Production Safeguard Branch of ZZAC” was established in the 1960s. However the maintenance service provided by the Production Safeguard Branch has become inadequate in recent years due to limitations in funding.

ZZAC has been very active in terms of promoting voluntary and charity activities. For example, ZZAC hospital staff went to Tibet for voluntary work in 1975. According to the ZZAC internal newspaper, 29 voluntary and charity activities were reported from 1997 to 2004, including voluntary tree planting, voluntary work for ZZAC retired employees, voluntary work with problem youth, voluntary road crossing patrols, charity donation for disaster relief, etc. However, there has been a decrease in the number of voluntary and charity activities that ZZAC employees have engaged in. It is understandable that the poor economic performance between 1999 and 2002 limited ZZAC’s ability to take part in voluntary activities. However, it is less intuitive that these activities have not increased despite the improvement in profitability after 2002 (the gross profit of 2003 and 2004 was 3.6 times and 1.8 times that in 1997 respectively). A return to earlier levels of charity activity might take time as the company may be uncertain about whether the improvement in profitability is a temporary phenomenon or if it will be sustained in the long run. This is confirmed by a field revisit in 2011. ZZAC has been taken out of the stock market due to its low profitability and some “political reasons” (as some locals put it).

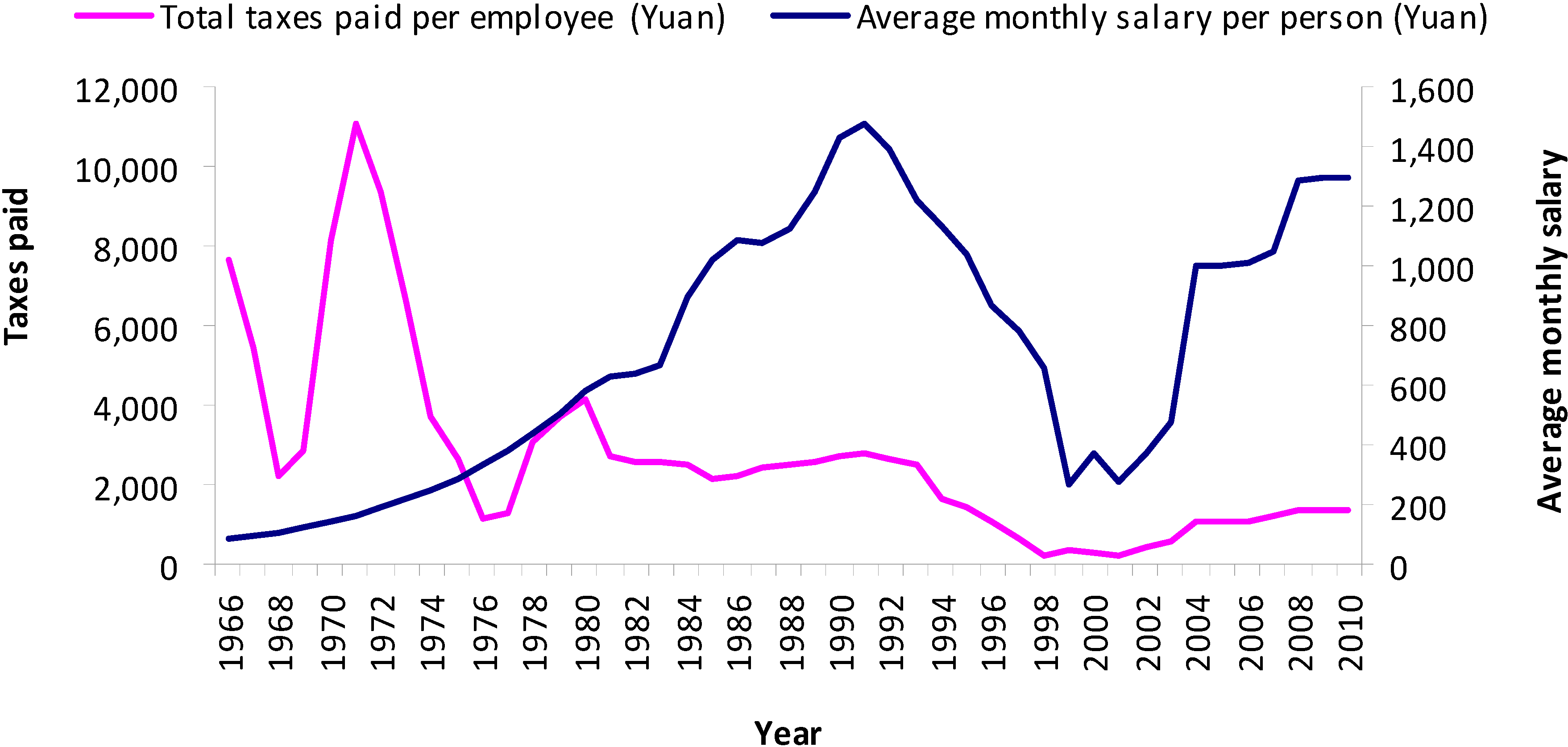

Figure 2 indicates that after yearly increases of average salary from 1966 to 1991, ZZAC employees’ pay fell significantly sometime between 1991 and 1997, and in 1999, the average monthly salary fell to its lowest level of 268 Yuan, which was only 18% of that in 1991 (if inflation was considered, the difference would even be greater). Since 2001, however, salaries have improved because of the restructuring measures and the improvement in labor productivity that these restructuring measures have generated. Even so, in 2004, the salary (997 Yuan) was still only 68% of that in 1991 (1473 Yuan). However, the average salary of all industrial enterprises in Zhengzhou in 2004 was 1195 Yuan per month, thus, ZZAC employees would appear to have been paid less than the city average. This is a dramatic change from the days when ZZAC’s salary levels were “

always higher than Zhengzhou’s average, especially from 1985 to 1993” [

49]. However, the salary level reported by ZZAC current employees is even lower.

Figure 2.

Average monthly salary and total taxes paid per employee in ZZAC.

Figure 2.

Average monthly salary and total taxes paid per employee in ZZAC.

There did not appear to be any gender discrimination in terms of ZZAC’s recruitment process and neither was there any evidence to suggest that women employees have been discriminated against during the process of redundancy. Women employees were asked whether there was support for pregnant employees at work and whether people can get paid for maternity leave. Some 40.3% of respondents admitted there was support for pregnant women at work, and 25.8% of them said there was paid maternity leave.

The survey indicates that 86.3% of current employees do not feel their views are represented in the company policy making. In addition, 94% of current employees do not know there is a system in place to deal with employee grievances i.e., help line or independent ombudsman ensuring employee anonymity for whistle blowing.

4.2. PAFs to the Rescue

If the picture provided by ZZAC is an illustration of a retreat from CSR, then is there any evidence that the PAFS have come to the rescue? The owners of the PAFS are previous ZZAC employees who mastered the technology while working in ZZAC and decided, from their perspective, to put their skills to better use. They still keep in touch with the old colleagues in ZZAC and through them they get to know the latest product and market information. PAF1, 2, and 3 are located in different villages around ZZAC in Zhengzhou City, and PAF4 located in an industrial park to the west of Zhengzhou. They rent land and properties from the local authority to start their business although their employees are rarely local and are normally from the owner’s hometown. They are either the owners’ close friends or relatives or someone recommended by the friends and relatives.

Talking about their social contribution, the PAFs have not provided any services such as health care, education, recreation and infrastructure comparable to those described above for ZZAC. Neither is there any sense that they see any responsibility for providing such services. A response from the owner of one of the PAF summarizes the general responses received:

“I work hard to run the factory. We hire people, and we pay tax. Are they not contributions?”

The proportion of male employees in the PAFs (87%) is much higher than that in ZZAC (46%). It appears that PAF owners are less willing to employ women because they feel that female workers are less-suited for labor and are only suited for office work. Amongst 39 PAF employees, only 8 are female. The PAFs provide no paid maternity leave, and in one of the PAFs, female workers had to quit their job to have children. PAF employees do not seem to request or be aware of any basic rights they are entitled to. For example, the workers of PAF3 seem happy with the fact that they are not allowed to go out to the village without permission from their manager. The average age of workers in the PAFs (32.69) is less than that of ZZAC (37.63). PAF owners stated that fit, young men can complete physical tasks more quickly than older male or female workers, and because these young men are in good health they are absent less often for medical reasons.

The survey indicated that the average monthly salary paid in the PAFs was 1021 Yuan in the 12 months to March 2005, while the average monthly salary of ZZAC employees was 694 Yuan in the 12 months prior to February 2005, and the average monthly salary of employees of all industrial enterprises in Zhengzhou in 2004 was 1195 Yuan. Hence it can be seen that the salary of the PAFs is close to the industry average and is significantly higher than in ZZAC. Around 51% of PAF employees earn more than half of their total family income; while only 15.4% of them earn less than a quarter of their family income. Therefore, around 20 families in villages (close or far away from Zhengzhou city) are relying on money from these four factories every month to make their living. Although the survey results suggest that the PAF employees received higher salaries than those working in ZZAC, responses of PAF employees during face-to-face interviews suggested that their monthly pay might be higher than they reported.

Like ZZAC, the PAFs have also made tax contributions to the local government exchequer. In Zhongyuan region (the regions in Zhengzhou City, where PAF1-3 and ZZAC are located) the tax revenue of ZZAC was 12.05% of the tax revenue of all industrial firms in 2004. In the same year, the tax revenue of all private industrial enterprises (PIR) was 4.38% of the total tax revenue of industrial enterprises (TIR), which was less than half of the tax revenue paid by ZZAC. This is not surprising given that most PAFs are small. Comparing the tax paid per employee, three of the PAFs are higher than ZZAC.

4.3. Pollution

Pollution produced during ZZAC’s manufacture of abrasive and grinding materials includes airborne pollution, wastewater, solid waste, machine noise and waste gases [

50]. The main air pollutants include soot, dust, SO

2 and several other types of toxic and non-toxic gases. SO

2 is produced during the process of drying grinding materials. Soot is produced during the process of carborundum and corundum smelting, and dust is produced during crushing, granule-making and grinding material processing. The dust is fine-grained with high-density and high-rigidity, including harmful particles such as silicon dioxide and alumina [

50]. Farmers living around ZZAC have suffered from environmental pollution produced by the company in the past. In two villages next to ZZAC, Luoda Temple and Shiyang Temple, it was reported that the soot discharged during the carborundum smelting process settled on the farmers’ vegetable fields and contaminated the vegetables, consequently many farmers suffered financial losses. The farmers also suffered from water pollution because of wastewater run-off into their vegetable fields.

There have been some long-term problems with the ventilation systems of ZZAC’s main production line due to a fault in design when ZZAC was established in 1956 [

51]. This, along with the ageing and inevitable degradation of the machinery, has made the pollution problems from ZZAC increasingly serious. The main occupational disease in ZZAC is Silicosis, which is a lung disease that develops over time when dust-containing silica is inhaled. There is no cure for silicosis to date and most silicosis patients die from its syndromes, which include lung cancer, lung infections, and in particular from tuberculosis (TB). Although ZZAC has started to take action on pollution abatement since 1970s, 218 workers were found to be suffering from some form of lung damage during the regular check from 1978 to 1980. Some of these sufferers went on to develop silicosis. In 1994, the cumulative investment in wastewater processing machinery was worth 1.2 million Yuan and investment in the dust control machinery worth six million Yuan (ZZAC internal document, 1995). At the same time, many environmental protection procedures and internal regulations were introduced to the company [

50].

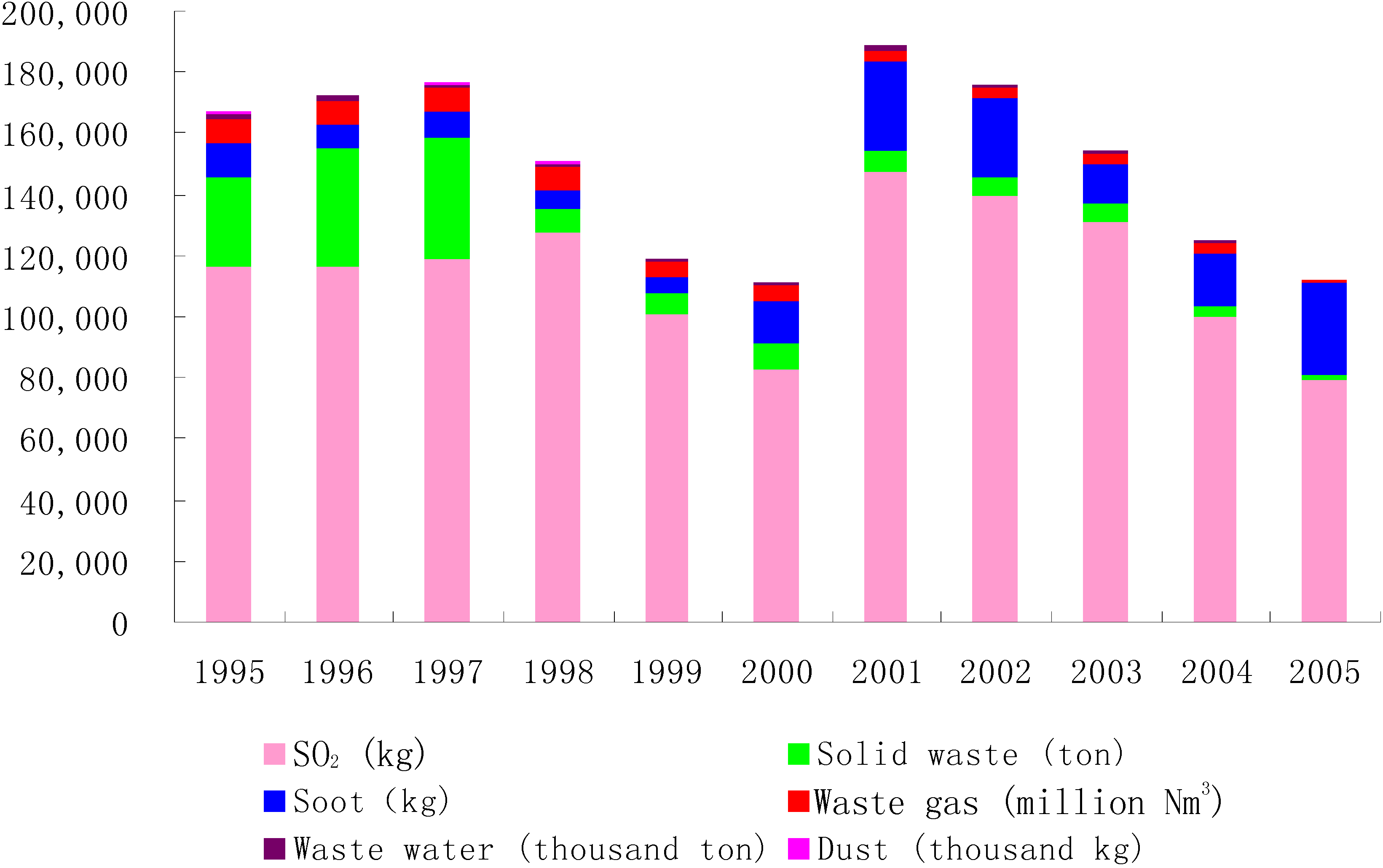

Figure 3 shows the main types of pollution from ZZAC and their changing trends from 1995 to 2005. It indicates that during this period wastewater produced by ZZAC has reduced by 77%, waste gas reduced by 89% and SO

2 by 32%. In 2005, solid waste output was 8% of that in 1995, while dust emission was only 0.6% of that in 1995. During the same period, only soot emission increased by 1.6 times. Hence according to the total pollutants produced, ZZAC’s environmental performance has improved over 11 years (1995–2005).

Despite this improvement, current employees and senior managers see ZZAC’s pollution record quite negatively. The majority of current employees (55%) believe that the pollution situation is either the same as it was or is getting worse. Only 27% felt that it was getting better. Surprisingly, even amongst the senior managers only 46% felt that the pollution situation was getting better. By way of contrast some 62% of former employees felt that the situation was improving, and only 7% felt that it was getting worse. Given ZZAC’s significant improvement in terms of emission of pollutants, the reluctance of current employees (and management) to perceive this improvement is surprising. However, with current employees still encountering the effects of pollution every day, it is understandable that they are less able to see the improvements. Many senior employees found questions regarding the environment too sensitive, but even so more than half of them admitted that pollution was the same or worsening. In addition, all 22 farmers in the two villages near ZZAC reported that there was no longer any pollution, though it had been very serious in the past.

Figure 3.

Pollutants produced by ZZAC between 1995 and 2005.

Figure 3.

Pollutants produced by ZZAC between 1995 and 2005.

Unsurprisingly, there is much less information on the environmental performance of the PAFs. From a sample of 39 PAF employees, seven (18.4%) thought there was no pollution from their factories. But around 42% thought there was air pollution, and around 80% of them thought there was noise pollution from their factories. In the village where PAF1 is located, only two in seven respondents (14%) thought these small factories caused environmental pollution. A senior officer of Zhengzhou Zhongyuan Environmental Monitoring Team, who is responsible for the environmental pollution of firms in Zhongyuan Region where PAF1-3 and ZZAC are located, thought that the pollution level of the PAFs was more serious than ZZAC, although she admitted that they do not assess the pollution levels of the PAFs in the way that they do for ZZAC.

5. Discussion

The results of the research discussed here illustrate how CSR has changed in parallel with the economic transition in China. The use of the case study approach allowed for a depth of insight that is often lacking with larger and more superficial datasets. Thus, it was possible to explore some of the deeper issues that arose from the pressures for change, and in particular how this allowed for the evolution of both ZZAC and PAFs. As a large SOE in China, ZZAC’s experience during the economic transition period bears a close resemblance to other large and medium size SOEs in China. The PAFs in the study have similar experience to many grassroots firms in China. However, it has to be acknowledged that every case has its own distinctive features and the companies chosen for this study are located in one of the most populated provinces in transitional China, and the PAFs have developed as offshoots of ZZAC to become independent businesses. This is one of the limitations of the study. But even these features are not that unusual, both in China and in other countries undergoing transition, and thus it may be argued that the lessons for CSR do have a wider applicability.

Admittedly, another limitation is that not all aspects of CSR have been included, largely due to the accessibility of the cases and the availability of data, but even so there are clear patterns and these match with the bigger picture of change in China. Prior to the economic reforms in 1978, social CSR in China was known to be very high and it had a higher priority than profitability. During the initial period of reform (1978–1992) CSR stayed the same, as the state ownership of Chinese firms had not changed. The market transition in 1993 completely changed the ownership structure of SOEs and private businesses were further encouraged to grow and blossom.

The Chinese state obviously intended to increase the profitability of SOEs by allowing them to shed their social responsibility. ZZAC did what many SOEs did at that time, but the fact is that even with less social obligations, ZZAC, like many SOEs who were so used to everything being planned for them, could not manage their own operation efficiently, and still partly rely on the state to keep them afloat. So the withdrawal of CSR did not in itself help improve their economic performance.

At the time of writing, the four PAFs in the study have improved both their economic performance and CSR. Salary and employment levels have increased significantly in recent years and there are signs that some managers have started to pay more attention to environmental issues. However, voluntary and philanthropic activities are still non-existent for the PAFs. As Lee [

52], in line with Hendry [

12], has noted, for SMEs, the business owners/managers can play a more important role in pushing CSR engagement than they may be able to do for large companies. Managers are also social beings with personal ethical standards, and their central challenge is “

how to arrive at some workable balance” between profit making and moral criteria [

53]. In the four PAFs, the owner of the firm with arguably the best CSR practice has the highest educational level. Although this evidence is limited, it does nonetheless raise the question as to whether there is a relationship between owner/manager’s educational level and the firm’s CSR practice. In China, the public has traditionally expected state companies such as ZZAC to be CSR providers and there are therefore fewer pressures on private companies to provide such services. But, as Weyzig [

54] argues, “

in the absence of stakeholder pressures, profitable CSR initiatives generally fall within the role of the private sector”. As a less favored customer of Chinese banks, this is a very good strategy for private businesses to survive and they may eventually outperform the state companies. However, while trying to increase the manager’s moral standard, China should adopt adequate institutional framework to secure the introduction of suitable social and environmental standards when parts of the economy have been transformed to a market system. Rules of economic, political, and social systems determine outcomes, if we, as a society, wish to improve these outcomes in terms of efficiency and equality, the appropriate instruments are changes in the rules [

55]. With Confucian virtues inherent in Chinese tradition, managers might willingly comply with acceptable rules. What is found in China, obviously, is that such rules are absent or insufficient or not enforced. The emphasis, then, should be laid on shaping the design of the regulation of economic markets so as to achieve ethical ends.