2.1. Integration Theory: Economic Integration, Social Integration, and Cultural/Identity Integration

Integration was first conceptualized by Gordon in 1964. In 1969, Park and Burgess gave one of the earliest definitions of integration, namely, “a process of interpenetration and fusion in which persons and groups acquire the memories, sentiments and attitude of other persons and groups and, by sharing their experience and history, are incorporated with them in a common cultural life” [

5]. Since then, integration studies have received much attention in ethnic relation studies.

In the 1990s, Alba and Nee presumed that as time went by, immigrants would become more integrated into the host society economically, socially, and culturally [

6]. This presumption identified lower-skill immigrant integration as economic, social, and cultural forms. On the basis of this identification, Wang and Fan supplemented identity integration, quoting Gordon’s classical integration framework [

5]. As identity integration (i.e., immigrants losing their own cultural/ethnic identity and instead accepting the cultural/ethnic identity of the dominant group) is a further discussion on immigrants’ cultural integration, in this regard, we perceive economic integration, social integration, and cultural/identity integration as the three key forms of immigrant integration.

Economic integration refers to immigrants achieving a more equal or average economic standing when compared to natives in the host society through social or human capital accumulation, employment, and homeownership [

5]. For instance, studies on Chinese, Indian, Slav, and Lebanese immigrants in Australia have shed light on a melting pot model where the employment rate and the income level of the third generation of the immigrants is more equal to the average in the host society than are those of the first and the second generation due to their language proficiency and better education [

13]. Immigrants in Denmark steadily increased their presence in an ethnic neighborhood at the beginning of their arrival, but significantly declined after 15 years due to their move to a neighborhood with a higher presence of Danes [

14].

Social integration refers to the extent to which immigrants adopt daily customs, norms, and practices indistinguishable from mainstream society, which can be measured by the extent of social adaptation, positioning, interaction, and identification [

5,

15]. For instance, over time, when compared to the first generation of Polish immigrants who immigrated to Australia to avoid WWII, the communication with the local natives among the second generation of Polish was more frequent due to their proficient English speaking, and the rate of their intermarriage with the natives was higher [

16].

Cultural/Identity integration refers to immigrants losing their own cultural/ethnic identity and instead accepting the identity of the dominant group in the host society over time. For instance, the South Africans in New Zealand reconstituted a feeling of home and identity belonging to the host society to integrate culturally through home-making [

17]. However, some multiculturalism scholars have disputed that cultural/identity integration does not necessarily mean losing one’s original identity while acquiring a new one [

18]. In fact, pan-ethnic identities, signifying the coexistence of the original identity and the new one, are more common [

5]. For instance, as time went by, the original identity of Iraqis and Moroccans, measured by the degree to which the immigrants perceived themselves as Dutch, became weaker, but the frequency of social transnational contacts and ethnic cultural activities remained unchanged [

19].

Although, based on studies on the Burmese in Norway and on Filipinos in Canada, social and cultural elements play more essential roles in the lower-skill immigrants’ ethnic relations, economic aspects as the initial and substantial dynamics for immigration are still the most typical and influential ones [

20,

21]. Therefore, economic integration is “perhaps the most researched area of integration” [

22].

2.2. Passive Economic Integration: Immigration Policy and Economic Structure

Among the various factors acting on economic integration, immigration policy has been highlighted. A large number of studies have concluded that immigration policy regimes play dominant roles in the economic integration of immigrants. For instance, the employment rate and average income of Somali immigrants in the UK are better than those of their compatriots in the Netherlands due to the mature immigration policy regimes in the UK, as the UK has a longer and more complex migration history than the Netherlands [

23]. Better economic integration also took place for immigrants in Malmö, a Swedish city, and Genoa, an Italian city, both of which experienced a period of post-industrialization economic decline and implemented a series of pro-immigration policies to attract abundant immigrants for the demand for cheap labor [

8]. Thus, pro-immigration policies (e.g., equal access for immigrants to social welfare and employment training) and a multinational conception of citizenship (e.g., strengthening citizenship education, providing citizenship classes to immigrants) are supposed to significantly promote the economic integration of lower-skill immigrants while unfriendly immigration policies prohibit it [

24,

25].

Conversely, an exclusionary attitude in immigration policies may impede the economic integration of immigrants. For instance, as the context in countries is generally quite different to the West, certain receiving countries like Sweden have refused to recognize the immigrants’ skill certification obtained in their original country, which means that it is more difficult for immigrants in Sweden to find a job unless they receive compulsory employment training [

26]. The overregulated employment procedures and social housing applications in Finland have also become obstacles for Asian, African, and East European immigrants trying to make a living in the host society [

11].

Nevertheless, sometimes pro-immigration policies may also unexpectedly obstruct immigrants’ economic integration. For instance, a large proportion of Tamils, Turks, and Pakistanis in Oslo, engaged in low-skilled works or remaining jobless, present a much lower rate and weaker passion to relocate “upwards, outwards, and westwards” to live in better neighborhoods than their compatriots in other countries. This contradictory phenomenon results from the higher welfare in Oslo, as the local government provides adequate well-equipped social houses for homeless immigrants and complete welfare for the jobless immigrants. Therefore, the immigrants’ passion to work hard and to improve their living condition in Oslo is weak [

27]. Similar to the previous study, Copenhagen provides immigrants with diversified desirable social houses, which has decreased the Turkish and Somali immigrants’ passion to learn more skills, find higher-paid jobs, and live in a more integrated community [

28]. Therefore, hospitable policies for lower-skill immigrants may instead impede their economic integration.

Furthermore, some academics have pointed out that whether the immigration policy is hospitable or hostile to immigrants depends on the local economic structures. For instance, Malmö and Genoa are experiencing a period of economic decline due to post-industrialization, so both these two cities hold a “welcoming” attitude towards immigrants for cheap labor [

8]. The fluctuating process of Russian immigrants’ economic integration in Israel has also resulted from the dynamically changing economic relations between Russia and Israel. Once the employment situation in Russia becomes better, Russian immigrants present a lack of passion when finding a job in Israel as most of them would prefer to seek jobs in their homeland [

29]. Immigration policies in England and Wales have recently become more exclusionary towards immigrants because of the shortage of temporary accommodation and rising housing costs [

7].

In this regard, academics have highlighted the impacts caused by immigration policy, the welfare institution, and economic structure on the economic integration of immigrants. However, these three factors are all activated by the host society. In other words, the above-mentioned studies perceive the immigrants’ economic integration as a passive process as immigrants do not play a dominant role in economic integration.

2.3. Active Economic Integration: Informality, Social and Human Capital, and Ethnic Economy

However, over time, lower-skill immigrants do not always participate in economic integration only passively. Some recent studies have indicated that immigrants will also play an active role in economic integration through informality, social and human capital accumulation, and ethnic economy.

Informality provides lower-skill immigrants with a temporary springboard to earn for themselves. The informal economy employs immigrants in unregulated and unregistered sectors (e.g., street vendors, home-based work). In some host societies, as immigrants cannot be engaged in a formal job due to the nonrecognition of their skill qualifications or the mismatch of the employment training between the original and the host society, they divert to being employed in the informal economy [

30]. Although this phenomenon initially takes place in developing countries, it becomes more common in developed countries due to continuous immigration. Moreover, studies have presented that it is the informal employment of immigrants that offers adequate manual labor for dirty, dangerous, and demeaning jobs. For instance, agricultural work in the city outskirts in Greece is toilsome. Hence, although it is necessary for Greek cities, few natives would like to be engaged in it. Consequently, local landowners begin to hire skilled immigrants for agricultural manual work like ploughing, sowing, irrigating, weeding, and harvesting, privately and seasonally. This informal employment provides jobs for immigrants on the one hand, and provides certain toilsome but necessary jobs with manual labor on the other, which is eventually encouraged by local governments [

31]. Therefore, some scholars have disputed many studies that implicitly accept the opinion connecting informality to negative economic outcomes but arbitrarily overlook the positive effects on economic integration of immigrants [

10].

Accumulating human and social capital is another common route for lower-skill immigrants to promote economic integration actively as both capital accumulations contribute to business start-up or participation in the formal labor market [

32]. Human capital refers to observable human capital, like education level or work experience, and unobservable types, like ability and talent [

33]. A study on Burundian and Burmese in Michigan, United States indicated that the proficiency of language provided access to necessary information and employment opportunities for these two ethnic groups, which significantly benefited their economic integration [

34]. Social capital refers to the immigrants’ relationship with other people and their ability to make use of the relationship to improve their economic well-being in the host society. Additionally, the family network and friend network are the most common social capital used by immigrants [

35]. Moreover, the friend network is perceived as a more efficient route to economic integration as it can provide more valuable and diversified information related to employment while information provided by the family network is quite familiar to the individuals. This presumption has been proven by a study on day labor worker centers in the United States where immigrants, who seek employment information through a friend network built up at the worker centers, are more likely to be employed than their compatriots who stay at home and seek information through the family network [

36]. However, although the friend network is more efficient, immigrants generally rely on the family network as it is difficult to truly get in with others, especially the natives [

22,

35]. In this regard, intermarriage with the natives becomes a compromised route to building up both the family and friend networks simultaneously, which exerts positive effects on male immigrants in Sweden [

26].

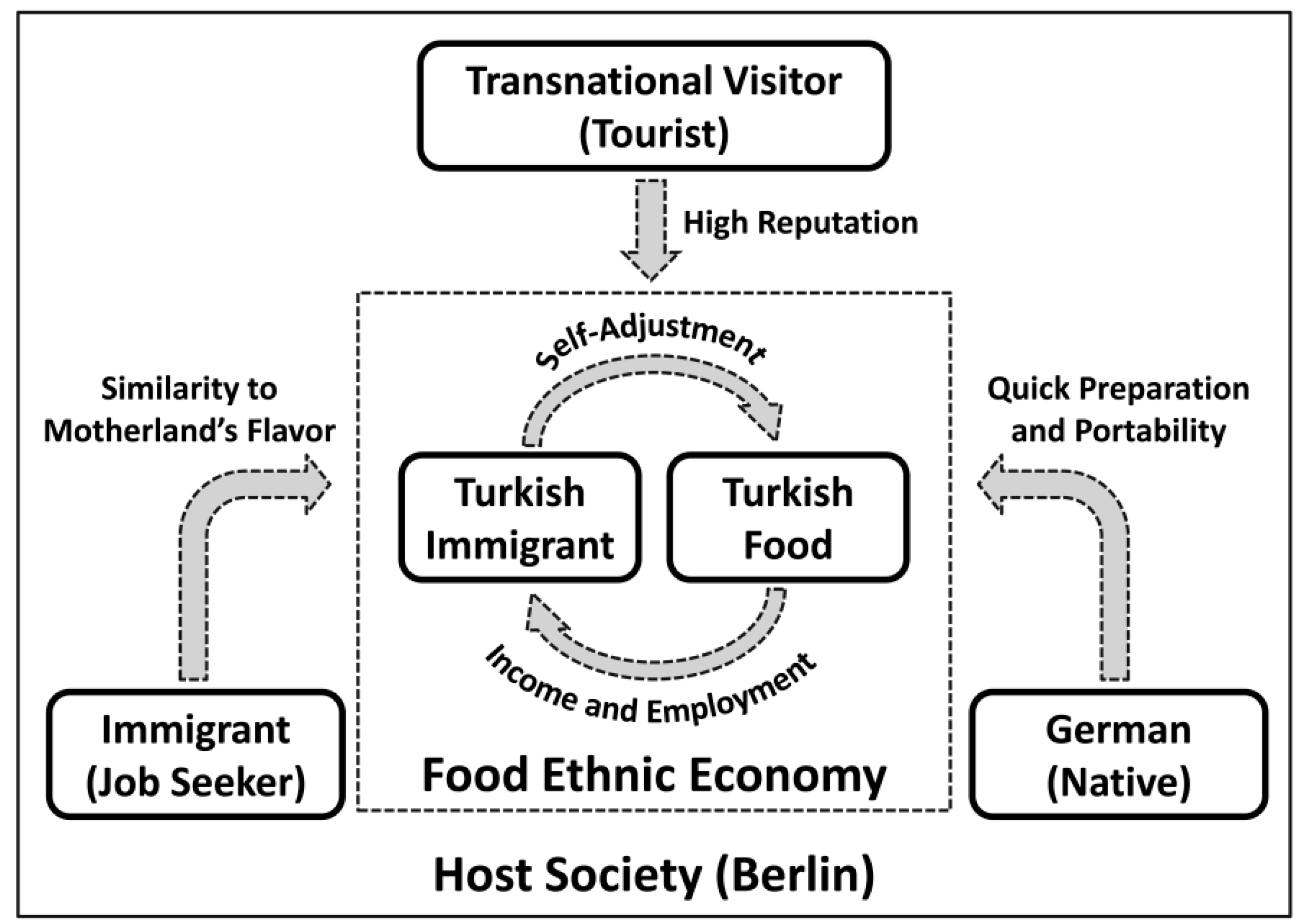

Although informality and capital accumulation are two active ways for lower-skill immigrants to integrate economically, both of them rely heavily on the players in the host society. Recently, academics have pointed out that there is another relatively more independent and more active economic integration route for immigrants named the ethnic economy. The ethnic economy was first systematically conceptualized by a sociologist called Bonacich in the 1980s as “a type of certain economic activities with strong and obvious ethnic attributes while employers and most employees are ethnic immigrants”. Subsequent studies on the Chinese in Los Angeles, Koreans in New York, Cubans in Miami, and Vietnamese in South California have generally focused on how the ethnic economy interacts with the formation of ethnic enclaves [

37]. However, a study on Latino immigrants in Charlotte implied a potential relationship between the ethnic economy and active economic integration. In this study, most of the natives in Charlotte moved to outer-ring suburbs for a better neighborhood environment in the 1960s, leaving a dilapidated and vacant inner space. Due to the surplus stock of retail shops and low-rental housing units, Latino immigrants began to agglomerate in the inner city, starting up retail shops for handicrafts or clothing as well as ethnic food restaurants alongside Central Avenue, which was once one of the best commercial places in Charlotte in the late 1950s. In this sense, the inner space of Charlotte has been transformed into a Latino ethnic economic space, which has retarded the pace of inner city decline and regenerated the downtown area unexpectedly. At present, many newly arrived immigrants usually head to this place for jobs and rental houses where they can also build up their friend network and accumulate their social capital. In a word, this case study more or less proved the presumption that the ethnic economy positively influences the economic integration of immigrants [

9].

To sum up, a transformation from passive economic integration to active economic integration has emerged in studies on lower-skill immigrants, and the ethnic economy exerts influential effects on the integration process. However, some empirical studies have disputed that a more active role played by immigrants in host societies does not mean an affirmative successful economic integration. Furthermore, inspired by the “three-way approach” model, whether immigrants can successfully integrate may also depend on actors beyond the two most highlighted actors (i.e., immigrants, natives) [

12]. For instance, although African immigrants in Guangzhou (China), who are mainly engaged in the apparel trade and stimulate the local economy positively (e.g., pay tax, increase volumes of export, provide jobs for other immigrants, and even some local Chinese), they are overregulated and rooted out by the local government for the sake of social stability and security [

38]. Although Estonian immigrants in Helsinki are active in making money, their motivation to engage in Finland permanently is weak due to the preferential policies on returnees implemented in their homeland, or due to their families’ expectations [

11].

Hence, although it has been proven that lower-skill immigrants are playing more active roles, two questions still remain uncertain or have been implicitly analyzed. (1) In the process of active economic integration through the ethnic economy, what are the roles played by the two traditionally highlighted actors (e.g., immigrants, natives)? (2) Enlightened by the “three-way approach” model, aside from the host society and immigrants, is there a third or fourth actor that exerts influence on the process of active economic integration?