Relational Benefit on Satisfaction and Durability in Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility

2.2. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Relational Benefit

2.2.1. Relational Benefit and Relational Commitment

2.2.2. Relational Benefit and Relational Authenticity

2.2.3. Strategic CSR Satisfaction and Durability

3. Research Methods

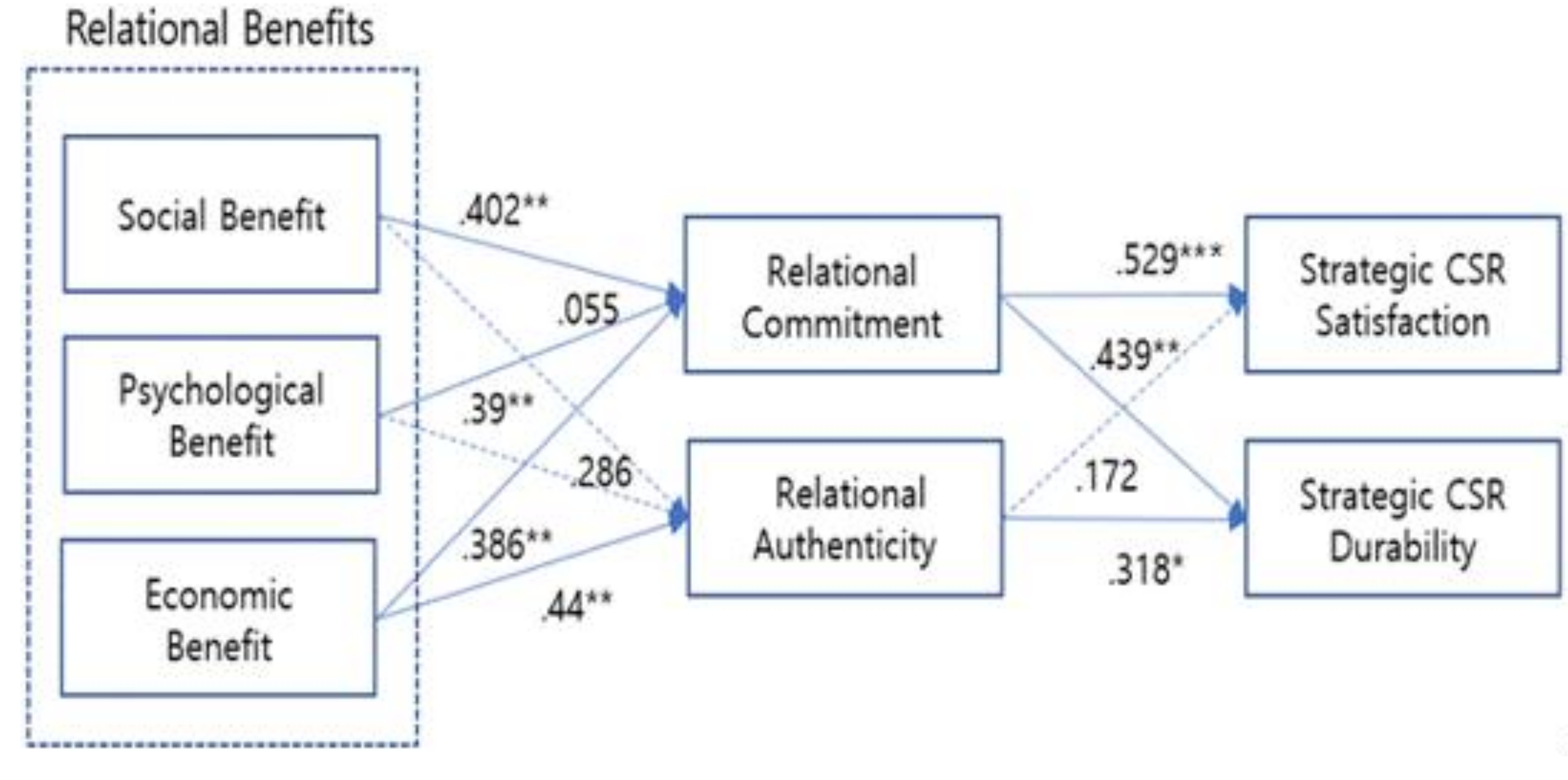

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Variables and Analytic Approach

4. Results

4.1. Demographics of Respondent

4.2. Analysis Results of Reliability and Validity

4.3. Analysis Results of Structural Model

4.4. Mediated Effect

5. Discussion

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Janggu, T.; Joseph, C.; Madi, N. The current state of Corporate Social Responsibility among industrial companies in Malaysia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2007, 3, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Palazzo, G. The new political role of business in a globalized world: A review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 899–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, S.J.; Kwon, I.S. Corporate Social Responsibility as a strategic means to attract foreign investment: Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, E.B. An empirical study on shared value created by CSR activities of Korean corporations. Korean Assoc. Logos Manag. 2012, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Kim, H.O. Exploring the organizational culture’s moderating role of effects of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) on firm performance: Focused on corporate contributions in Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, M.; Marc; Chefneux, L.; Goldberg, A.; Heimburg, J.V.; Patrignani, N.; Schofield, M.; Shilling, C. Responsible innovation: A complementary view from industry with proposals for bridging different perspectives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Badia, M.T.; Montllor-Serrats, J.; Tarrazon-Rodon, M.A. Efficiency and sustainability of CSR projects. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.P.; Gremler, D.D.; Bitner, M.J. Relational benefits in services industries: The customer’s perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1998, 26, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibility and Accountabilities of the Businessman; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of Corporate Social Responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizations stakeholder. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Dacin, A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1996, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.; Wright, P.M. Corporate Social Responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, K.; Starkey, K. The dilemmas of internationalization: Corporate Social Responsibility in the multinational corporation. Br. J. Manag. 2014, 25, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eells, R.; Walton, C. Conceptual Foundations of Business; Richard D. Irwin Inc.: Homewood, CA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, S.P. Dimensions of Corporate Social Performance: An analytical framework. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1975, 17, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, D.E. Management and Society; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, J.; Sundgren, A.; Schneeweis, T. Corporate Social Responsibility and firm financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 854–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The four faces of corporate citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 1998, 100, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Strategy and society. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Del Baldo, M. Developing Businesses and Fighting Poverty: Critical Reflections on the Theories and Practices of CSR, CSV, and Inclusive Business; Chapter 11, Part III, pp. 191–223 in L. Pate, C. Wankel (Eds.), Emerging Research Directions in Social Entrepreneurship, Advances in Business Ethics Research; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, S.O.; Vertigans, S. (Eds.) Stages of Corporate Social Responsibility. From Ideas to Impacts; Springer International Publishing: Ove Jakobsen, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.K. The current state of global CSR and corporate shared value for corporations. Korea Int. C. Agency 2014, 13, 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Husted, B.W.; Allen, D.B. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and value creation among large firms: Lessons from the Spanish experience. Long Range Plan. 2007, 40, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeon, B.G.; Kim, E.T. Social Innovation Business; Idea Flight: Seoul, Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliland, D.I.; Bello, D.C. Two sides to attitudinal commitment: The effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2002, 30, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bames, J. Closeness, strength, and satisfaction: Examining the nature of relationship between providers of financial services and their retail customer. Psychol. Mark. 1997, 14, 765–790. [Google Scholar]

- Bitner, M. Building service relationships: It’s all about promises. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronroos, C. Relationship approach to marketing in service contexts: The marketing and organizational behavior interface. J. Bus. Res. 1990, 20, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.R.; Shelby, D.H. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conze, O.; Bieger, T.H.; Laesser, C.H.; Riklin, T.H. Relationship intentions as a mediator between relational benefit and customer loyalty in the tour operation industry. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.R.; Kim, S.I. The influence of relational benefits on relational quality and long-term orientation in the family restaurant. J. Food Serv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2011, 14, 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L.L. Relationship marketing of service: Growing interest emerging perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, B.; Ford, D. Industrial buyer resources and responsibilities and the buyer-seller relationship. Ind. Mark. Purch. 1986, 1, 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.S. The effect of interactional quality perceived by hotel consumer on relational commitment and intent to relationship continuity focused on the moderating effect of the trust. Tour. Res. 2012, 35, 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, K.; Wilson, C. Have we studied, should we study, and can we study the development of commitment? Methodological issues and the developmental study of work-related commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, K.E.; Beatty, S.E. Customer benefits and company consequences of customer-salesperson relationships in retailing. J. Retail. 1999, 75, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulaga, W. Capturing value creation in business relationships: A customer perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2003, 32, 677–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, E.Y. A study on the relationship benefit perception and long-term relationship intention among fashion product consumers. J. Korean Soc. Cloth. Text. 2006, 30, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C. Corporate Social Responsibility: Today’s assignment. Bus. Law Rev. 2008, 22, 149–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan, S. Determinant of long-term orientation in buyer-seller relationship. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Zaltman, G.; Deshpande, R. Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, S.Y.; Nam, H.J. Corporate Social Responsibility and firm value of global companies in Korea. Korean Ind. Econ. Assoc. 2010, 29, 753–777. [Google Scholar]

- Patrizia, G. Social performance enhances financial performance, benefits from CSR. The Annals of the University of Oradea. Econ. Serv. J. 2012, 21, 112–212. [Google Scholar]

- Soellner, A. Commitment in Exchange Relationships: The Role of Switching Costs in Building and Sustaining Competitive Advantages. In Relationship Marketing: Theory, Methods and Applications; Sheth, J., Paratiyar, A., Eds.; Emory University: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.; Weitz, B. The use of pledges to build and sustain commitment in distribution channels. J. Mark. Res. 1992, 29, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundlach, G.T.; Achrol, R.S.; Mentzer, J.T. The structure of commitment in exchange. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macneil, I.R. The New Social Contract: An Inquiry into Modern Contractual Relations; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Hakansson, H.; Johanson, J. Dyadic business relationships within a business network context. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D. The development of buyer-seller relationships in industrial markets. Eur. J. Mark. 1980, 14, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, T.; Colwell, A.; Cunningham, P.H. The emergence of Corporate Social Responsibility in Chile: The importance of authenticity and social network. J. Bus. Eth. 2009, 86, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connora, A.; Shumate, M.; Meister, M. Walk the line: Active moms define Corporate Social Responsibility. Public Relat. Rev. 2008, 34, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.L.; Arnould, E.J.; Tierney, P. Going to extremes: Managing service encounters and assessing provider performance. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D. Authenticity: Brands, Fakes, Spin, and the Lust for Real Life; Harper Collins: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Harter, S. Authenticity. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Snyder, C.R., Lopez, S.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 382–394. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. Authenticity and sincerity in Tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M. The ‘real thing’: Branding authenticity in the luxury wine trade. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, J.H.; Pine, B.J. What Consumers Really Want: Authenticity; Harvard Business School Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forehand, M.R.; Grier, S. When is honesty the best policy? The effect of stated company intent on consumer skepticism. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 349–356. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.; Korschun, D. The role of Corporate Social Responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.; Kahn, B. Corporate sponsorships of philanthropic activities: When do they impact perception of sponsor brand? J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifon, N.J.; Choi, S.M.; Trimble, C.S.; Li, H. Congruence effects in sponsorship. J. Advert. 2004, 33, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.; Webb, D.; Mohr, L. Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Shin, S.H.; Kim, S.J. The influence of consistency and distinction attribution of corporate’s cause-related behavior on attitude toward corporate. Korean J. Consum. Advert. Psychol. 2005, 6, 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Drumwright, M.E. Company advertising with social dimension: The role of noneconomic criteria. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.M.; Alcon, D.S. Cause marketing: A new direction in the marketing of corporate responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 1991, 8, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendapudi, N.; Leonard, L.B. Customers’ motivations for maintaining relationships with service providers. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Narus, J.A. A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, R.A. The Diversity of Human Relationships. In Describing Relationships; Auhagen, A.E., Salisch, M.V., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 7–35. [Google Scholar]

- Duck, S. Dynamics of Relationships; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, F.R.; Schurr, P.H.; Oh, S. Developing buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 51, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibb, S.; Meadows, M. The application of a relationship marketing perspective in retail banking. Serv. Ind. J. 2001, 21, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; Pitt, L.; Berthon, P. Analyzing and reducing customer defections. Long Range Plan. 1996, 29, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, C.I.; Woo, C.B. The effect of relational benefit on relational commitment and long-term relationship orientation among hotel customers. Tour. Res. 2015, 40, 169–190. [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Thurau, T.; Groth, M.; Paul, M.; Gremler, D.D. Are all smiles created equal? How emotional contagion and emotional labor affect service relationships. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Lindgreen, L.A.; Vink, W.M. Projecting authenticity through advertising: Consumer judgments of advertisers’ claims. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Choi, H.C. The influence about authenticity of Corporate Social Responsibility on the corporate attitude. Korean J. J. Commun. Stud. 2012, 56, 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, S.G.; Yang, J.H. A study on relationship among relational benefits, satisfaction and customer loyalty; Focused on the moderating effects of consumer’s innovativeness & rationality. J. Mark. Manag. Res. 2013, 18, 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, H.S.; Ju, H.J. The study on the effect of relationship benefits on commitment, intention to alienate, and loyalty in open market. J. Korea Serv. Manag. Soc. 2012, 13, 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, XVIII, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Gulas, C.S.; Gruca, T.S. Corporate giving behavior and decision-maker social consciousness. J. Bus. Ethics 1999, 19, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, C.M. Motives for corporate philanthropy in El Salvador: Altruism and political legitimacy. J. Bus. Eth. 2000, 27, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.Y.; Lee, H.S. Determinants of corporate philanthropy: Application of several econometric methodologies. Sogang J. Bus. 2009, 20, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller, B. Business-NGO Partnership; Ethical Corporation Report: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T. Corporate-NGO Partnership: Learning from Case Studies; Corporate-NGO Partnership in Asia-Pacific, Yamamoto, T., Ashizawa, K.G., Eds.; Japan Center for International Exchange: Tokyo, Japan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, D.W.; Kang, C.H.; Huh, S.Y. A study of the partnership between corporations and NPOs: Exploring success factors and failure factors in the partnership. J. Korean Soc. Welf. Adm. 2013, 15, 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, K.S.; Choi, S.R. Effects of Korean franchise bakery’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) authenticity on brand trust and brand loyalty. J. Foodserv. Manag. Soc. Korea 2014, 17, 7–28. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Key Researchers | Main Concept |

|---|---|---|

| 1950s | Bowen (1953) [10] | Emphasis on corporate social value and responsibility |

| 1960s | Eells & Walton (1961) [16] | Emphasis on corporate social responsibility from the ethical point of view |

| 1970s | Sethi (1975) [17], Carroll (1979) [18] | Emphasis on companies’ desirable social role and leadership in the dynamic social system |

| 1980s | McFarland (1982) [19] McGuire et al. (1988) [20] | Insisting on the need for recognition based on mutual reliance with stakeholders |

| 1990s | Carroll (1991, 1998) [12,21] Brown and Dacin (1996) [13] | Emphasis on solving social and economic problems resulting from corporate activities |

| 2000s | McWilliams and Siegel (2006) [14] Porter and Kramer (2011) [3] Kotler and Kramer (2006) [22] | Insisting on accomplishing social and economic goals through long-term profits by managing the company with strategic activities |

| Factors | Operational Definition | Items | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Benefit | Intimacy with partners and solving social problems | 3 | Gwinner et al. (1998) [9] Suh and Ju (2012) [82] |

| Psychological Benefit | A sense of comfort and safety and conviction in long-term partnerships | 3 | |

| Economic Benefit | Economic benefits partners feel when developing relations with companies | 3 | |

| Relational Commitment | The desire to keep valuable relations | 3 | Moorman et al. (1992) [44] |

| Relational Authenticity | Authenticity and reliability formed in relationships | 2 | Beckman et al. (2009) [53] Lee and Choi (2012) [82] |

| Strategic CSR Satisfaction | Satisfaction in the relationship with certain stakeholders regarding strategic CSR activities | 3 | Reynolds and Beatty (1999) [39] |

| Strategic CSR Durability | The willingness to continue relations with certain stakeholders regarding strategic CSR activities | 3 | Rifon et al. (2004) [61] Ellen, Webb and Mohr (2006) [66] |

| Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47 | 41.6 |

| Female | 66 | 58.4 | |

| Total | 113 | 100 | |

| Age | Younger than 30 | 75 | 66.4 |

| 30 s | 18 | 15.9 | |

| 40 s | 15 | 13.3 | |

| 50 or older | 5 | 4.4 | |

| Total | 113 | 100 | |

| Education (degree) | Bachelor’s | 31 | 27.4 |

| Master’s | 66 | 58.4 | |

| Doctoral | 16 | 14.2 | |

| Total | 113 | 100 | |

| Activity period | less than 3 years | 50 | 44.2 |

| 3–5 years | 39 | 34.5 | |

| 5 years or longer | 24 | 21.2 | |

| Total | 113 | 100 | |

| Category | Variable | Standard Loading Value | Standard Error | T Value | p Value | CR | AVE | Cronbach α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | Social Benefit | 0.659 | 0.795 | 0.570 | 0.690 | |||

| 0.774 | 0.231 | 5.333 | *** | |||||

| 0.531 | 0.162 | 4.454 | *** | |||||

| Psychological Benefit | 0.667 | 0.840 | 0.636 | 0.667 | ||||

| 0.623 | 0.2 | 4.598 | *** | |||||

| 0.595 | 0.193 | 4.492 | *** | |||||

| Economic Benefit | 0.558 | 0.839 | 0.638 | 0.671 | ||||

| 0.660 | 0.2 | 4.591 | *** | |||||

| 0.760 | 0.259 | 4.733 | *** | |||||

| Parameter | Relational Commitment | 0.746 | 0.887 | 0.724 | 0.769 | |||

| 0.714 | 0.137 | 6.979 | *** | |||||

| 0.715 | 0.141 | 6.982 | *** | |||||

| Relational Authenticity | 0.674 | 0.872 | 0.776 | 0.721 | ||||

| 0.837 | 0.242 | 4.959 | *** | |||||

| Dependent value | Strategic CSR Satisfaction | 0.798 | 0.906 | 0.763 | 0.852 | |||

| 0.847 | 0.146 | 9.058 | *** | |||||

| 0.802 | 0.14 | 8.689 | *** | |||||

| Strategic CSR Durability | 0.549 | 0.831 | 0.631 | 0.649 | ||||

| 0.528 | 0.253 | 4.09 | *** | |||||

| 0.821 | 0.288 | 4.701 | *** |

| Category | AVE | Social Benefit | Psychological Benefit | Economic Benefit | Relational Commitment | Relational Authenticity | Strategic CSR Satisfaction | Strategic CSR Durability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Benefit | 0.570 | 0.755 | ||||||

| Psychological Benefit | 0.636 | 0.424 | 0.798 | |||||

| Economic Benefit | 0.638 | 0.257 | 0.207 | 0.799 | ||||

| Relational Commitment | 0.724 | 0.665 | 0.665 | 0.504 | 0.851 | |||

| Relational Authenticity | 0.776 | 0.284 | 0.399 | 0.464 | 0.552 | 0.881 | ||

| Strategic CSR Satisfaction | 0.763 | 0.438 | 0.27 | 0.466 | 0.607 | 0.434 | 0.874 | |

| Strategic CSR Durability | 0.631 | 0.319 | 0.274 | 0.536 | 0.588 | 0.518 | 0.461 | 0.794 |

| χ2 (p) | df | p | χ2/Degree of Freedom | RMR | GFI | AGFI | NFI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 204.365 | 157 | 0.007 | 1.302 | 0.033 | 0.848 | 0.797 | 0.767 | 0.931 | 0.917 | 0.052 |

| Hypothesis (Channel) | Channel Coefficient | T Value | p Value | Adopted or Dismissed | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hypothesis 1-1 (social benefit → relational commitment) | 0.402 | 3.135 | 0.002 ** | Adopted | 0.737 |

| hypothesis 1-2 (psychological benefit → relational commitment) | 0.390 | 2.946 | 0.003 ** | Adopted | |

| hypothesis 1-3 (economic benefit → relational commitment) | 0.386 | 3.172 | 0.002 ** | Adopted | |

| hypothesis 2-1 (social benefit → relational authenticity) | 0.055 | 0.403 | 0.687 | dismissed | 0.356 |

| hypothesis 2-2 (psychological benefit → relational authenticity) | 0.286 | 1.880 | 0.060 | dismissed | |

| hypothesis 2-3 (economic benefit → relational authenticity) | 0.440 | 2.809 | 0.005 ** | Adopted | |

| hypothesis 3-1 (relational commitment → satisfaction) | 0.529 | 4.046 | *** | Adopted | 0.396 |

| hypothesis 4-1 (relational authenticity → satisfaction) | 0.172 | 1.434 | 0.152 | dismissed | |

| hypothesis 3-2 (relational commitment → durability) | 0.439 | 2.863 | 0.004 ** | Adopted | 0.426 |

| hypothesis 4-2 (relational authenticity → durability) | 0.318 | 2.182 | 0.029 * | Adopted |

| Dependent Variable | Explanatory Variable | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategic CSR satisfaction | Relational commitment | 0.529 | - | 0.529 | |

| Relational authenticity | 0.172 | - | 0.172 | ||

| Social benefit | - | 0.213 *** | (Relational commitment) | 0.222 | |

| 0.009 | (Relational authenticity) | ||||

| Psychological benefit | - | 0.207 *** | (Relational commitment) | 0.256 | |

| 0.049 * | (Relational authenticity) | ||||

| Economic benefit | - | 0.204 ** | (Relational commitment) | 0.280 | |

| 0.076 * | (Relational authenticity) | ||||

| Strategic CSR durability | Relational commitment | 0.439 | - | 0.439 | |

| Relational authenticity | 0.318 | - | 0.318 | ||

| Social benefit | - | 0.177 *** | (Relational commitment) | 0.194 | |

| 0.017 * | (Relational authenticity) | ||||

| Psychological benefit | - | 0.171 *** | (Relational commitment) | 0.262 | |

| 0.091 * | (Relational authenticity) | ||||

| Economic benefit | - | 0.169 ** | (Relational commitment) | 0.309 | |

| 0.140 * | (Relational authenticity) | ||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.; Kim, B.; Oh, S. Relational Benefit on Satisfaction and Durability in Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041104

Kim M, Kim B, Oh S. Relational Benefit on Satisfaction and Durability in Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability. 2018; 10(4):1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041104

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Minseok, Boyoung Kim, and Sungho Oh. 2018. "Relational Benefit on Satisfaction and Durability in Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility" Sustainability 10, no. 4: 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10041104