Influence of Technological Assets on Organizational Performance through Absorptive Capacity, Organizational Innovation and Internal Labour Flexibility

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Top management support for technology (TMS) reflects the development of a work environment that supports knowledge management and information systems. TMS can, in turn, provide the appropriate funds and resources, encourage teams and help teams overcome problems, fostering cross-functional cooperation, knowledge and communication [20].

- Technological skills may be understood as one of the “dimensions that distinguishes and provides the knowledge set needed to enable a core capability” [21] (p. 113). This dimension of skills encompasses both firm-specific techniques and scientific understanding. It provides the basis for the firm’s competencies and sustainable competitive advantage in a particular business [22]. In applying this understanding to technological issues [21], our study stresses that technological skills constitute the entire technical system, a system that usually traces its roots to the firm’s first products.

- Technological Distinctive Competencies (TDCs) represent “the organization’s expertise in mobilizing various scientific and technical resources through a series of routines and procedures which allow new products and production processes to be developed and designed” [23] (p. 508).

2. Theoretical Background

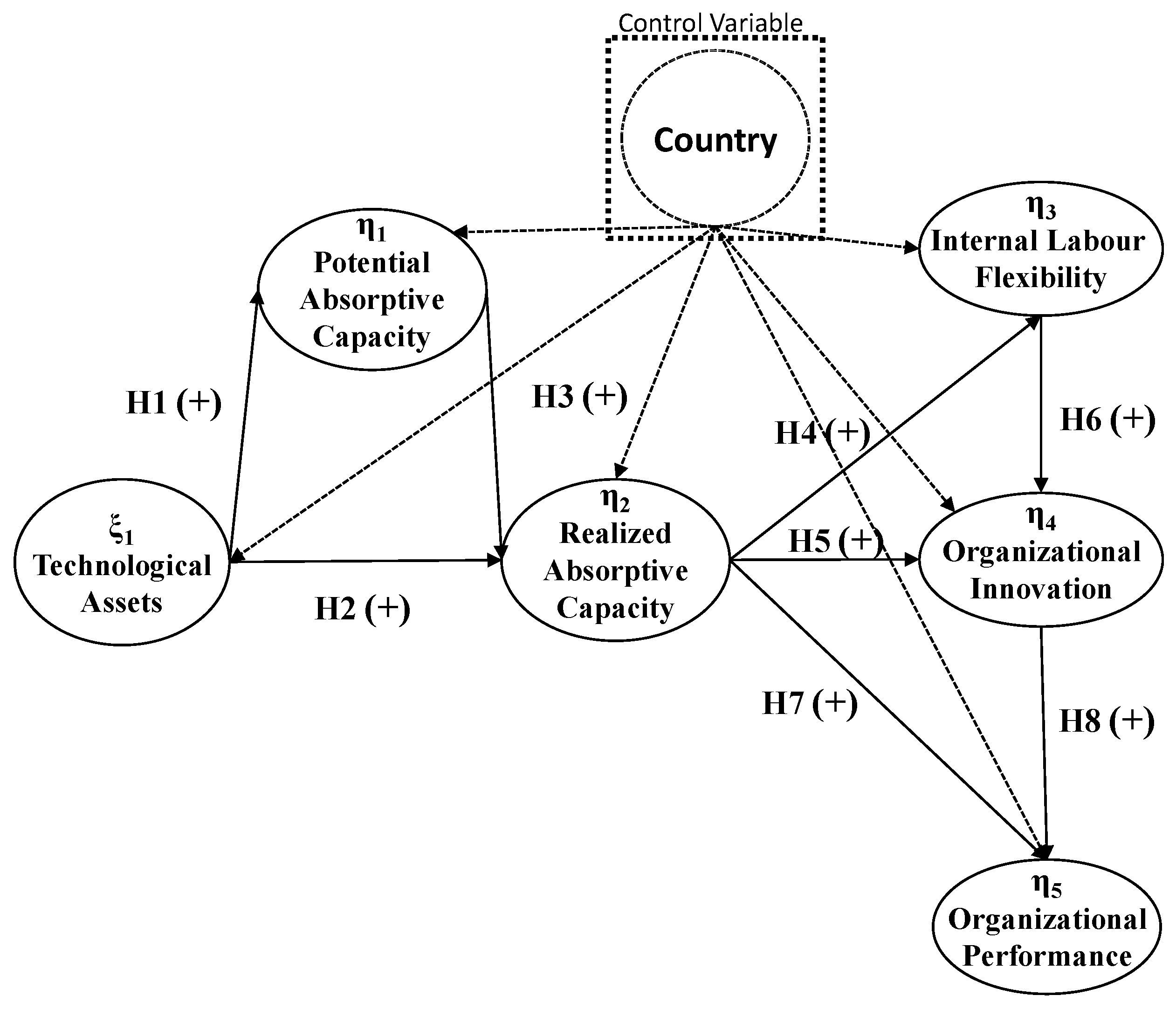

3. Hypotheses

3.1. The Influence of Technological Assets on Potential and Realized Absorptive Capacity

3.2. The Influence of Potential Absorptive Capacity on Realized Absorptive Capacity

3.3. The Influence of Realized Absorptive Capacity on Internal Labour Flexibility and Organizational Innovation

3.4. The Influence of Internal Labour Flexibility on Organizational Innovation

3.5. The Influence of Realized Absorptive Capacity and Organizational Innovation on Organizational Performance

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Model and Analysis

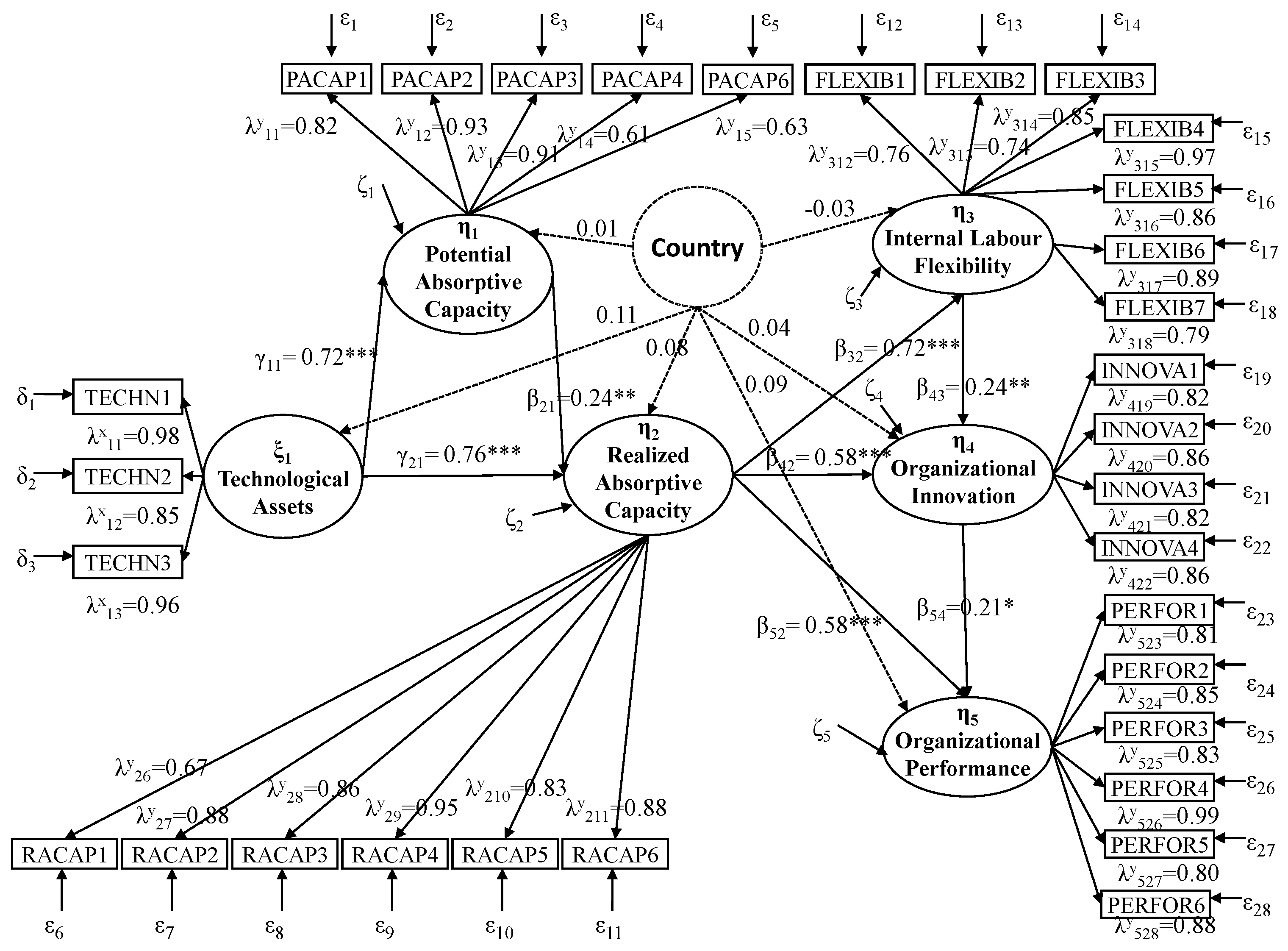

5. Results

6. Conclusions and Future Research

6.1. Discussion

6.1.1. Theoretical Implications

6.1.2. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

Technological Assets

- Top management cultivates technology project champions.

- Top management ensures adequate funding of technology research and development.

- Top management restructures work processes to leverage technological opportunities in the organization.

- Top management facilitates technology transfer throughout the organization.

- Are very superior to those of closest competitors in hardware and operating systems performance.

- Are very superior to those of closest competitors in business applications software performance.

- Are very superior to those of closest competitors in communications services efficiency.

- Are very superior to those of closest competitors in the generation programming languages.

- Capability to obtain information about the status and progress of science and relevant technologies.

- Capability to generate advanced technological processes.

- Capability to assimilate new technologies and useful innovations.

- Capability to attract and retain qualified scientific-technical staff.

- Capability to master, generate or absorb basic and key technologies.

- Effectiveness in setting up programs oriented to internal development of technological or technology absorption competencies, either from R&D centres or from suppliers and customers.

- There is close personal interaction between the two organizations.

- The relation between the two organizations is characterized by mutual trust.

- The relation between the two organizations is characterized by a high level of reciprocity.

- Workers must communicate regularly with colleagues about work-related issues.

- The main capabilities of the two organizations are very similar.

- The organizational cultures of the two organizations are compatible.

- Interdepartmental meetings are organized to discuss the development and tendencies of the organization.

- The important data are transmitted regularly to all units.

- When something important occurs, all units are informed within a short time.

- The organization has the capabilities or abilities necessary to ensure that knowledge flows within the organization and is shared among the different units.

- There is a clear division of functions and responsibilities regarding use of information and knowledge obtained from outside.

- Capabilities and abilities are needed to exploit the information and knowledge obtained from the outside.

- If the need emerged, employees of this firm could easily be transferred to other jobs with responsibilities similar to those of their current jobs.

- If the need emerged, employees of this firm could easily be transferred to more qualified jobs.

- Employees in this firm attempt constantly to update their skills and abilities.

- Employees in this firm are quick to learn new procedures and processes introduced in their job.

- When employees detect problems in performing their jobs, they voluntarily try to identify the causes of these problems.

- Employees in this department act efficiently in uncertain and ambiguous circumstances.

- Employees in this department exchange ideas with people from different areas of the organization.

- Spending on new products/services development activities.

- The number of products/services added by the organization that are already on the market.

- The number of new products/services that the organization introduced on the market for first time.

- Emphasis on R&D, technological leadership and innovations.

- The rate of new product introduction on the market.

- Organizational performance measured by return on assets (ROA).

- Organizational performance measured by return on equity (ROE).

- Organizational performance measured by return on sales (ROS).

- Organization’s market share in its main products and markets.

- Growth of sales in its main products and markets.

References

- Jones, G.K.; Lanctot, A., Jr.; Teegen, H.J. Determinants and performance impacts of external technology acquisition. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; George, G. Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Giarratana, M.S.; Torrisi, S. Foreign entry and survival in a knowledge-intensive market: Emerging economy countries’ international linkages, technology competences, and firm experience. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2010, 4, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Aligning enterprise knowledge and knowledge management systems to improve efficiency and effectiveness performance: A three-dimensional fuzzy-based decision support system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 91, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rojas, R.; Garcia Morales, V.J.; Garcia-Sanchez, E. The influence on corporate entrepreneurship of technological variables. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2011, 11, 984–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Morales, V.J.; Bolivar Ramos, M.T.; Martin-Rojas, R. Technological variables and absorptive capacity’s influence on performance through corporate entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.T.; Linton, J.D. The strategy-technology firm fit audit: A guide to opportunity assessment and selection. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, I.L.; Sandvik, K. The impact of market orientation on product innovativeness and business performance. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2003, 20, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotabe, M.; Jiang, C.X.; Murray, J.Y. Managerial ties, knowledge acquisition, realized absorptive capacity and new product market performance of emerging multinational companies: A case of China. J. World Bus. 2011, 46, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.J.P.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.J.; Volberda, H.W. Managing potential and realized absorptive capacity: How do organizational antecedents matter? Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammad, M.F.; YedidiaTarba, S.; Liu, Y.; Glaister, K.G. Knowledge transfer and cross-border acquisition performance: The impact of cultural distance and employee retention. Int. Bus. Rev. 2016, 25, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Reani, M. The rise of mobile computing for Group Decision Support Systems: A comparative evaluation of mobile and desktop. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2017, 104, 16–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran Martin, I.; Roca Puig, V.; Escrig Tena, A.; BouLlusar, J.C. Internal labour flexibility from a resource-based view approach: Definition and proposal of a measurement scale. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 1576–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Rodríguez, A.L.; Roldán, J.L.; Ariza-Montes, J.A.; Leal-Millán, A. From potential absorptive capacity to innovation outcomes in project teams: The conditional mediating role of the realized absorptive capacity in a relational learning context. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2014, 32, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolivar Ramos, M.T.; Garcia Morales, V.J.; Martin Rojas, R. The effects of information technology on absorptive capacity and organisational performance. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2013, 25, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Sanchez, A.; Vela Jimenez, M.J.; Perez Perez, M.; Carnicer, L.P. Innovación y flexibilidad de recursos humanos: El efecto moderador del dinamismo del entorno. Rev. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empresa 2011, 20, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Rojas, R.; García Morales, V.J.; Bolívar Ramos, M.T. Influence of technological support, skills and competencies, and learning on corporate entrepreneurship in European technology firms. Technovation 2013, 33, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Rojas, R.; Fernandez-Pérez, V.; García-Sánchez, E. Encouraging organizational performance through the influence of technological distinctive competencies on components of corporate entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 397–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez Barrionuevo, M.M.; Garcia Morales, V.J.; Molina, L.M. Validation of an instrument to measure absorptive capacity. Technovation 2011, 31, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Morales, V.J.; Llorens Montes, F.J.; Verdu Jover, A.J. The effects of transformational leadership on organizational performance through knowledge and innovation. Br. J. Manag. 2008, 19, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard-Barton, D. Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, J.C.; Leal, A.; Roldan, J.L. Information technology as a determinant of organizational learning and technological distinctive competencies. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinstein, A.; Goldman, A. Characterizing the technology firm: An exploratory study. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, E.; Martín Rojas, R.; Fernández Pérez, V. ¿Los activos tecnológicos fomentan la capacidad de absorción? Contab. Negocios 2016, 11, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargadon, A.B. Firms as knowledge brokers: Lessons in pursuing continuous innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1998, 40, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camison, C.; Fores, B. Knowledge absorptive capacity: New insights for its conceptualization and measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.; Levinthal, D. Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, J.; Porter, M.; Stern, S. The determinants of national innovative capacity. Res. Policy. 2002, 31, 899–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PDMA. The PDMA Glossary for New Product Development. Product Development and Management Association, 2004. Available online: http://www.pdma.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2012).

- Urquijo, J. Teoría de las Relaciones Sindicato-Gerenciales; Editorial Texto; Departamento de Estudios Laborales-UCAB: Caracas, Venezuela, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Avlonitis, G.J.; Salavou, H. Entrepreneurial orientation of SMEs, product innovativeness, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JimenezJimenez, D.; Sanz Valle, R. Innovación, aprendizaje organizativo y resultados empresariales: Un estudio empírico. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empresa 2006, 29, 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J.B. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doranova, A.; Costa, I.; Duysters, G. Absorptive Capacity in Technological Learning in Clean Development Mechanism Projects; UNU-MERIT Working Paper #2011-010; UNU-MERIT: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, P.H.J. Why share knowledge? The influence of ICT on the motivation for knowledge sharing. Knowl. Process Manag. 1999, 6, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Millán, A.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal Rodríguez, A.L.; Ortega Gutierrez, J. IT and relationship learning in networks as drivers of green innovation and customer capital: Evidence from the automobile sector. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 444–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ramamurthy, K. Understanding the link between information technology capability and organizational agility: An empirical examination. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 931–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M.; Huysman, M.; Steinfield, C. Enterprise social media: Definition, history, and prospects for the study of social technologies in organizations. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2013, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.; Leidner, D.E. Review: Knowledge management and knowledge management systems: Conceptual foundations and research issues. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides Velasco, C.A.; Quintana Garcia, C. Proceso y sistemas organizativos para la gestión del conocimiento: el papel de la calidad total. Bol. ICE Econ. 2005, 2838, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, E.; García-Morales, V.J.; Bolívar-Ramos, M.T. The influence of top management support for ICTs on organisational performance through knowledge acquisition, transfer, and utilization. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2017, 11, 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, S.A. Enhancing Knowledge Acquisition through the Use of ICT. In Decision Support in an Uncertain and Complex World: The IFIP TC8/WG8.3 International Conference 2004; Merredith, R., Shanks, G., Arnott, D., Carlsson, S., Eds.; Monash University: Prato, Italy, 2004; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- Iansiti, M.; MacCormack, A. Developing products on internet time. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kambil, A.; Friesen, G.; Sundaram, A. Co-creation: A new source of value. Outlook Mag. 1999, 3, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Apostolou, D.; Mentzas, G.; Sakkas, N. Knowledge networking in supply chains: A case study in the wood/furniture sector. Inf. Knowl. Syst. Manag. 1999, 1, 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bolisani, E.; Scarso, E. Information technology management: A knowledge-based perspective. Technovation 1999, 19, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S. Knowledge management technologies and applications-literature review from 1995 to 2002. Expert Syst. Appl. 2003, 25, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyndale, P. A taxonomy of knowledge management software tools: Origins and applications. Valuat. Program Plan. 2002, 25, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Choi, S.; Lee, H.; Yoo, Y. The impact of information technology and transactive memory systems on knowledge sharing, application, and team performance: A field study. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2010, 34, 833–854. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, R.; Sanchez Manzanares, M.; Gil, F.; Gibson, C. Team implicit coordination processes: A team knowledge-based approach. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boland, R.J.; Tenkasi, R.V. Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing. Organ. Sci. 1995, 6, 350–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambamurthy, V.; Bharadwaj, A.; Grover, V. Shaping agility through digital options: Reconceptualizing the role of information technology in contemporary firms. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.T.; Nohria, N.; Tierny, T. What’s your strategy for managing knowledge? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1999, 77, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, G.; Lampert, C.M. Entrepreneurship in the large corporation: A longitudinal study of how established firms create breakthrough inventions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, K.; Papalexandris, A.; Papachroni, M.; Ioannou, G. Absorptive capacity, innovation, and financial performance. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Jimenez-Jimenez, D. The effect of absorptive capacity on innovativeness: Context and information systems capability as catalysts. Br. J. Manag. 2012, 23, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, T.L.; Sawyer, J.E.; Neale, M.A. Virtualness and knowledge in teams: Managing the love triangle of organizations, individuals, and information technology. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 27, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran Martin, I.; Escrig Tena, A.; Bou Llusar, J.C.; Roca Puig, V. Influencia de las prácticas de recursos humanos en la flexibilidad de los empleados. Cuad. Econ. Dir. Empresa 2013, 16, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.M.; Snell, S.A. Toward a unifying framework for exploring fit and flexibility in strategic human resource management. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 756–772. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg, P.T.; Van der Velde, M.E.G. Relationships of functional flexibility with individual and work factors. J. Bus. Psychol. 2005, 20, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Gibson, D.E.; Doty, D.H. The effects of flexibility in employee skills, employee behaviors, and HR practices on firm performance. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 622–640. [Google Scholar]

- Rajeswari, K.S.; Anantharaman, R.N. Development of a Scale to Measure Stress among Software Professionals: A Factor Analytic Study. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCPR Conference, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 10–12 April 2003; Trauth, E., Ed.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, R.; Spann, M. Collective entrepreneurship at Qualcomm: Combining collective and entrepreneurial practices to turn employee ideas into action. R&D Manag. 2011, 41, 442–456. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, J.; Meager, N. Is flexibility just a flash in the pan? Pers. Manag. 1986, 18, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Blyton, P.; Morris, J. HRM and the limits of flexibility. In Reassessing Human Resource Management; Blyton, B., Turnbull, P., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1992; pp. 116–130. [Google Scholar]

- Looise, J.C.; Van Riemsdijk, M.; De Lange, F. Company labour flexibility strategies in the Netherlands: An institutional perspective. Empl. Relat. 1998, 20, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, J.; Sheehan-Quinn, M. Labour market flexibility, human resource management and corporate performance. Br. J. Manag. 2001, 12, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquijo, J. Teoría de las Relaciones Industriales. De cara al siglo XXI; Departamento de Estudios Laborales-UCAB: Caracas, Venezuela, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, S.J.; Guimaraes, T. Corporate culture, absorptive capacity and IT success. Inf. Organ. 2005, 15, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newey, L.R.; Zahra, S.A. The evolving firm: How dynamic and operating capabilities interact to enable entrepreneurship. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, C.M. Squeezing harder doesn’t always work: Continuing the search for consistency in innovation research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyer, L.; Ericksen, J. In pursuit of marketplace agility: Applying precepts of self-organizing systems to optimize human resource scalability. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2005, 44, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujan, H.; Weitz, B.A.; Kumar, N. Learning orientation, working smart, and effective selling. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abernathy, W.; Utterback, J. Patterns of industrial innovation. Technol. Rev. 1978, 80, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Camison, C. Sobre cómo medir las competencias distintivas: Un examen empírico de la fiabilidad y validez de los modelos multi-item para la medición de los activos intangibles. In Proceedings of the First International Conferenceof the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, Universidad Carlos III, Madrid, Spain, 9–11 December 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Prajogo, D.I.; Ahmed, P.K. Relationships between innovation stimulus, innovation capacity, and innovation performance. R&D Manag. 2006, 36, 499–515. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. 1977. Available online: http://repository.upenn.edu/marketing_papers/17 (accessed on 23 April 2017).

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, A.M.; Linnehan, F. Formalized HRM structures: Coordinating equal employment opportunity or concealing organizational practice? Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 787–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organization research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, A.; Davidson, N. Examining possible antecedents of IT impact on the supply chain and its effect on firm performance. Inf. Manag. 2003, 41, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, G.; Muhanna, W.A.; Barnety, J.B. Information technology and the performance of the customer service process: A resource-based analysis. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 625–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Environment, corporate entrepreneurship, and financial performance: A taxonomic approach. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Bolívar-Ramos, M.T.; Martín-Rojas, R. Technological variables and absorptive capacity’s influence on performance through corporate entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.Y.; Kotabe, M. Sourcing strategies of U.S. service companies: A modified transaction-cost analysis. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 791–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbin, D.W. Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allarakhia, M.; Walsh, S. Managing knowledge assets under conditions of radical change: The case of the pharmaceutical industry. Technovation. 2011, 31, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Verde, M.; Martín-de Castro, G.; Amores-Salvadó, J. Intellectual capital and radical innovation: Exploring the quadratic effects in technology-based manufacturing firms. Technovation 2016, 54, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.T.; Hsieh, L.F. An innovation knowledge game piloted by merger and acquisition of technological assets: A case study. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2006, 23, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J.F. Asset profiles for technological innovation. Res. Policy. 1995, 24, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-de Castro, G.; Delgado-Verde, M.; Navas-López, J.E.; Cruz-González, J. The moderating role of innovation culture in the relationship between knowledge assets and product innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2013, 80, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteeg, T.; Baumann, M.J.; Weil, M.; Moniz, A.B. Exploring emerging battery technology for grid-connected energy storage with constructive technology assessment. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 115, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Díaz, N.L.; Aguiar-Díaz, I.; De Saá-Pérez, P. The effect of technological knowledge assets on performance: The innovative choice in Spanish firms. Res. Policy. 2008, 37, 1515–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, M. El cambio de escenario, in Ordoñez, Miguel (Coordinator). In Las nuevas fronteras del empleo; Pearson Education, S.A. Prentice Hall: Madrid, Spain, 2003; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ketter, W.; Peters, M.; Collins, J.; Gupta, A. A multiagent competitive gaming platform to address societal challenges. MIS Q. 2016, 40, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Knowledge management in startups: Systematic literature review and future research agenda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total | Austria | Belgium | Denmark | France | Germany | Italy | Poland | Spain | The Netherlands | United Kingdom | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size % Response | 125 12.80% | 105 15.23% | 118 13.55% | 96 16.66% | 72 22.22% | 84 19.04% | 87 18.39% | 75 21.33% | 70 22.85% | 68 23.52% | 900 17.77% |

| Methodology | Structured questionnaire | ||||||||||

| Procedure | Stratified sample with proportional allocation | ||||||||||

| Universe of Population | 5441 firms | ||||||||||

| Sample Size (% response) | 160 (17.77%) firms | ||||||||||

| Sampling Error | 7.7% | ||||||||||

| Confidence Level | 95%, p – q = 0.50; Z = 1.96 | ||||||||||

| Comparison | Means | t-test 95% Conf. Int. | |||||||||

| Mean No. Employees | 125.37 | 128.66 | 122.31 | 126.53 | 127.46 | 136.18 | 123.93 | 128.37 | 123.68 | 138.07 | >0.776 −112.580 118.271 |

| Mean Sales volume | 53.63 | 63.27 | 57.05 | 64.14 | 58.66 | 57.25 | 59.87 | 58.50 | 57.58 | 63.83 | >0.825 −109.454 88.441 |

| Mean Invest. IT as. | 3.98 | 4.37 | 4.46 | 5.06 | 5.04 | 5.04 | 5.68 | 5.41 | 5.15 | 5.33 | >0.656 −10.088 6.675 |

| Mean Budget R&D | 1.15 | 1.36 | 1.73 | 1.43 | 1.83 | 1.71 | 2.05 | 1.91 | 1.30 | 1.66 | >0.431 −2.790 1.270 |

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.-Technology Assets | 5.055 | 1.111 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 2.-Pot. Absorptive Capacity | 5.045 | 1.371 | 0.282 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| 3.-Real Absorptive Capacity | 5.254 | 1.277 | 0.270 *** | 0.478 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 4.-Int. Labour Flexibility | 4.999 | 1.153 | 0.443 *** | 0.218 ** | 0.224 ** | 1.000 | |||

| 5.-Organizational Innovation | 4.850 | 1.343 | 0.485 *** | 0.244 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.363 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 6.-Organizational Performance | 4.727 | 1.142 | 0.404 *** | 0.144 † | 0.301 *** | 0.215 ** | 0.341 *** | 1.000 | |

| 7.-Country | 5.5 | 2.881 | 0.115 | 0.095 | 0.077 | 0.005 | 0.134 † | 0.155 * | 1.000 |

| Variables | Items | λ* | R2 | C.R. | AVE | Correlation Confidence Interval | Goodness of Fit Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Assets (T) | TECHN1 | 0.98 *** (54.97) | 0.96 | 0.953 | 0.873 | T-PAC 0.47–0.67 T-RAC 0.56–0.74 T-ILF 0.67–0.82 T-OI 0.68–0.84 T-OP 0.64–0.80 PAC-RAC 0.70–0.85 PAC-ILF 0.40–0.59 PAC-OI 0.39–0.59 PAC-OP 0.38–0.58 RAC-ILF 0.41–0.59 RAC-OI 0.46–0.65 RAC-OP 0.53–0.69 ILF-OI 0.60–0.76 ILF-OP 0.46–0.64 OI-OP 0.57–0.75 | χ2420 = 603.30 (p > 0.01) GFI = 0.94 AGFI = 0.93 NNFI = 0.96 IFI = 0.97 NCP = 183.30 CFI = 0.97 RMSEA = 0.05 |

| TECHN2 | 0.87 *** (31.68) | 0.75 | |||||

| TECHN3 | 0.95 *** (45.21) | 0.90 | |||||

| Potential Absorptive Capacity (PAC) | PACAP1 | 0.82 *** (25.37) | 0.68 | 0.888 | 0.620 | ||

| PACAP2 | 0.92 *** (36.00) | 0.85 | |||||

| PACAP3 | 0.89 *** (29.14) | 0.79 | |||||

| PACAP4 | 0.63 *** (14.18) | 0.51 | |||||

| PACAP6 | 0.63 *** (13.31) | 0.52 | |||||

| Realized Absorptive Capacity (RAC) | RACAP1 | 0.65 *** (14.92) | 0.50 | 0.939 | 0.722 | ||

| RACAP2 | 0.90 *** (32.63) | 0.82 | |||||

| RACAP3 | 0.87 *** (32.55) | 0.76 | |||||

| RACAP4 | 0.94 *** (36.40) | 0.88 | |||||

| RACAP5 | 0.84 *** (26.85) | 0.71 | |||||

| RACAP6 | 0.87 *** (29.45) | 0.76 | |||||

| Internal Labour Flexibility (ILF) | FLEXIB1 | 0.73 *** (18.80) | 0.54 | 0.943 | 0.703 | ||

| FLEXIB2 | 0.76 *** (20.04) | 0.57 | |||||

| FLEXIB3 | 0.84 *** (27.70) | 0.71 | |||||

| FLEXIB4 | 0.96 *** (40.71) | 0.92 | |||||

| FLEXIB5 | 0.87 *** (32.10) | 0.76 | |||||

| FLEXIB6 | 0.89 *** (32.70) | 0.79 | |||||

| FLEXIB7 | 0.80 *** (22.71) | 0.64 | |||||

| Organizational Innovation (OI) | INNOVA1 | 0.83 *** (23.44) | 0.67 | 0.903 | 0.701 | ||

| INNOVA2 | 0.84 *** (24.80) | 0.71 | |||||

| INNOVA3 | 0.81 *** (24.50) | 0.66 | |||||

| INNOVA4 | 0.87 *** (28.18) | 0.75 | |||||

| Organizational Performance (OP) | PERFOR1 | 0.80 *** (25.12) | 0.65 | 0.941 | 0.730 | ||

| PERFOR2 | 0.83 *** (24.73) | 0.69 | |||||

| PERFOR3 | 0.83 *** (28.49) | 0.69 | |||||

| PERFOR4 | 0.99 *** (57.01) | 0.99 | |||||

| PERFOR5 | 0.78 *** (20.26) | 0.61 | |||||

| PERFOR6 | 0.88 *** (31.10) | 0.77 |

| Direct Effects | t | Indirect Effects | t | Total Effects | t | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect From | To | |||||||

| Technological Assets | → | Potential Absorptive Capacity | 0.72 *** | 13.14 | 0.72 *** | 13.14 | ||

| Technological Assets | → | Realized Absorptive Capacity | 0.76 *** | 8.66 | 0.17 ** | 3.21 | 0.93 *** | 14.41 |

| Technological Assets | → | Internal Labour Flexibility | 0.67 *** | 13.96 | 0.67 *** | 13.96 | ||

| Technological Assets | → | Organizational Innovation | 0.70 *** | 15.02 | 0.70 *** | 15.02 | ||

| Technological Assets | → | Organizational Performance | 0.58 *** | 15.50 | 0.58 *** | 15.50 | ||

| Potential Absorptive Capacity | → | Realized Absorptive Capacity | 0.24 ** | 2.97 | 0.24 ** | 2.97 | ||

| Potential Absorptive Capacity | → | Internal Labour Flexibility | 0.17 ** | 2.94 | 0.17 ** | 2.94 | ||

| Potential Absorptive Capacity | → | Organizational Innovation | 0.18 ** | 2.97 | 0.18 ** | 2.97 | ||

| Potential Absorptive Capacity | → | Organizational Performance | 0.17 ** | 2.97 | 0.17 ** | 2.97 | ||

| Realized Absorptive Capacity | → | Internal Labour Flexibility | 0.72 *** | 11.22 | 0.72 *** | 11.22 | ||

| Realized Absorptive Capacity | → | Organizational Innovation | 0.58 *** | 6.57 | 0.17 ** | 2.84 | 0.75 *** | 11.82 |

| Realized Absorptive Capacity | → | Organizational Performance | 0.58 *** | 6.09 | 0.16 * | 2.12 | 0.74 *** | 12.32 |

| Internal Labour Flexibility | → | Organizational Innovation | 0.24 ** | 2.81 | 0.24 ** | 2.81 | ||

| Internal Labour Flexibility | → | Organizational Performance | 0.05 | 1.61 | 0.05 | 1.61 | ||

| Organizational Innovation | → | Organizational Performance | 0.21 * | 2.12 | 0.21 * | 2.12 | ||

| Country | → | Technological Assets | 0.11 † | 1.78 | 0.11 † | 1.78 | ||

| Country | → | Potential Absorptive Capacity | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.08 † | 1.75 | 0.09 | 1.32 |

| Country | → | Realized Absorptive Capacity | 0.08 | 1.40 | 0.02 † | 1.88 | 0.10 ** | 2.99 |

| Country | → | Internal Labour Flexibility | −0.03 | −0.46 | 0.07 ** | 2.99 | 0.04 † | 1.78 |

| Country | → | Organizational Innovation | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.13 ** | 3.04 | 0.17 ** | 2.80 |

| Country | → | Organizational Performance | 0.09 | 1.62 | 0.12 *** | 3.44 | 0.21 *** | 3.94 |

| Goodness of Fit Statistics | χ2452 = 698.76 (p > 0.01) GFI = 0.94 AGFI = 0.93 ECVI = 5.35 AIC = 850.76 CAIC = 1160.48 NNFI = 0.95 IFI = 0.96 PGFI = 0.80 PNFI = 0.81 NCP = 246.76 CFI = 0.96 RMSEA = 0.059 | |||||||

| Model | Description | χ2 | ∆χ2 | RMSEA | NNFI | ECVI | AIC | NCP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Theoretical | 698.76 | 0.059 | 0.95 | 5.35 | 850.76 | 246.76 | |

| 2 | Without Tech. Assets to Pot. Abs. Capacity | 764.63 | 65.87 | 0.066 | 0.94 | 5.75 | 914.63 | 311.63 |

| 3 | Without Tech. Assets to Real Abs. Capacity | 740.71 | 41.95 | 0.063 | 0.94 | 5.60 | 890.71 | 287.71 |

| 4 | Without Pot. Abs. Capacity to Real Abs. Capacity | 704.31 | 5.34 | 0.059 | 0.89 | 5.37 | 854.31 | 251.31 |

| 5 | Without Real Abs. Capacity to Int. Lab. Flexibility | 763.72 | 64.96 | 0.066 | 0.94 | 5.75 | 913.72 | 310.72 |

| 6 | Without Real Abs. Capacity to Org. Innovation | 733.91 | 35.15 | 0.062 | 0.95 | 5.56 | 883.91 | 280.91 |

| 7 | Without Int. Lab. Flexibility to Org. Innovation | 705.89 | 7.13 | 0.059 | 0.95 | 5.38 | 855.89 | 252.89 |

| 8 | Without Real Abs. Capacity to Org. Performance | 722.20 | 23.44 | 0.061 | 0.95 | 5.49 | 872.20 | 269.20 |

| 9 | Without Org. Innovation to Org. Performance | 702.75 | 3.99 | 0.059 | 0.95 | 5.36 | 852.75 | 249.75 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Sánchez, E.; García-Morales, V.J.; Martín-Rojas, R. Influence of Technological Assets on Organizational Performance through Absorptive Capacity, Organizational Innovation and Internal Labour Flexibility. Sustainability 2018, 10, 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030770

García-Sánchez E, García-Morales VJ, Martín-Rojas R. Influence of Technological Assets on Organizational Performance through Absorptive Capacity, Organizational Innovation and Internal Labour Flexibility. Sustainability. 2018; 10(3):770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030770

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Sánchez, Encarnación, Víctor J. García-Morales, and Rodrigo Martín-Rojas. 2018. "Influence of Technological Assets on Organizational Performance through Absorptive Capacity, Organizational Innovation and Internal Labour Flexibility" Sustainability 10, no. 3: 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10030770