The Short-Term Effects of Rice Straw Biochar, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizer on Rice Yield and Soil Properties in a Cold Waterlogged Paddy Field

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biochar for Soil Amendment

2.2. Experimental Site

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.4. Soil Sampling and Analysis

2.5. Rice Sampling and Analysis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Crop Yield, Yield Components and Biomass Production

3.2. Nutrient Use Efficiency, Concentration and Uptake

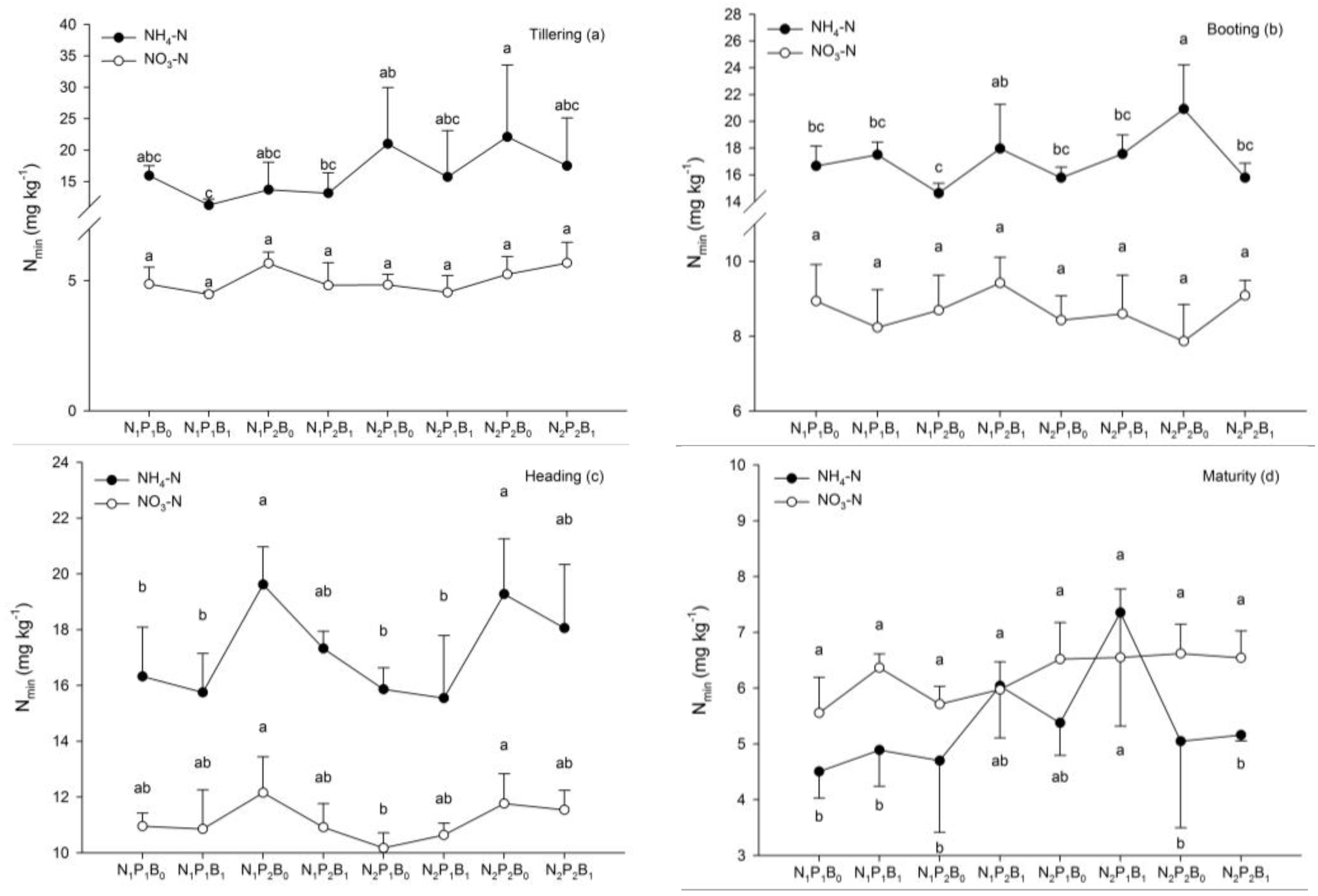

3.3. Soil Properties

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Properties

4.2. Nutrient Uptake

4.3. Crop Production

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiong, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, G.; Xu, C.; Mao, C. Influences of combing ridge and no-tillage on rice yield and soil temperature and distribution of aggregate in cold waterlogged field. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2014, 30, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, K.; Xu, P.; Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, R.; Gu, W.; Li, W.; Sun, L. Effects of supplementary composts on microbial communities and rice productivity in cold water paddy fields. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Wang, M.K.; Wang, F.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Li, Q.; Lin, C.; Lin, X. Effects of open drainage ditch design on bacterial and fungal communities of cold waterlogged paddy soils. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2013, 44, 983–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahrawat, K.L. Organic matter accumulation in submerged soils. Adv. Agron. 2003, 81, 169–201. [Google Scholar]

- Muthayya, S.; Sugimoto, J.D.; Montgomery, S.; Maberly, G.F. An overview of global rice production, supply, trade, and consumption. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1324, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, S.; Faqir, A.; Sher, M.; Javed, M.A.; Waqar, M.Q.; Ali, M.A. Efficacy of different chemicals for the management of bacterial leaf blight of rice (Oryza sativa L.) at various locations of adaptive research zone Sheikhupura. Pak. J. Phytopathol. 2016, 28, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- China Statistical Yearbook. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2017/indexch.htm (accessed on 8 January 2018).

- Yuan, L. Development of hybrid rice to ensure food security. Rice Sci. 2014, 21, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D.J.; Andrews, J.; Pauly, D. The effort factor: Evaluating the increasing marginal impact of resource extraction over time. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 25, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, L.; Strokal, M.; Chu, Y.; Kroeze, C. Exploring nutrient management options to increase nitrogen and phosphorus use efficiencies in food production of China. Agric. Syst. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Feng, S.; Reidsma, P.; Qu, F.; Heerink, N. Identifying entry points to improve fertilizer use efficiency in Taihu Basin, China. Land Use Policy 2014, 37, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellarby, J.; Siciliano, G.; Smith, L.; Xin, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, K.; Jie, L.; Meng, F.; Inman, A.; Rahn, C. Strategies for sustainable nutrient management: Insights from a mixed natural and social science analysis of Chinese crop production systems. Environ. Dev. 2017, 21, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Feng, J.; Zhai, S.; Dai, Y.; Xu, M.; Wu, J.; Shen, M.; Bian, X.; Koide, R.T.; Liu, J. Long-term ditch-buried straw return alters soil water potential, temperature, and microbial communities in a rice-wheat rotation system. Soil Tillage Res. 2016, 163, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Ren, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, T.; Inubushi, K. Effect of rice residues on carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide emissions from a paddy soil of subtropical China. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2007, 178, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Xing, G. Successive straw biochar application as a strategy to sequester carbon and improve fertility: A pot experiment with two rice/wheat rotations in paddy soil. Plant Soil 2014, 378, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Biochar for environmental management: An introduction. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science, Technology and Implementation, 2nd ed.; Lehmann, J., Joseph, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar effects on soil biota—A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, L.D.; Zehetner, F.; Rampazzo, N.; Wimmer, B.; Soja, G. Long-term effects of biochar on soil physical properties. Geoderma 2016, 282, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, A.S.; Miguez, F.E.; Laird, D.A.; Horton, R.; Westgate, M. Assessing potential of biochar for increasing water-holding capacity of sandy soils. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abujabhah, I.S.; Bound, S.A.; Doyle, R.; Bowman, J.P. Effects of biochar and compost amendments on soil physico-chemical properties and the total community within a temperate agricultural soil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 98, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąb, T.; Palmowska, J.; Zaleski, T.; Gondek, K. Effect of biochar application on soil hydrological properties and physical quality of sandy soil. Geoderma 2016, 281, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Lal, R. The biochar dilemma. Soil Res. 2014, 52, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yang, M.; Feng, Q.; Mcgrouther, K.; Wang, H.; Lu, H.; Chen, Y. Chemical characterization of rice straw-derived biochar for soil amendment. Biomass Bioenergy 2012, 47, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Thavamani, P.; Megharaj, M.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Naidu, R. Agronomic and remedial benefits and risks of applying biochar to soil: Current knowledge and future research directions. Environ. Int. 2016, 87, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Feng, Q.; Mcgrouther, K.; Yang, M.; Wang, H.; Wu, W. Effects of biochar amendment on rice growth and nitrogen retention in a waterlogged paddy field. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 15, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.F.; Meng, J.; Wang, Q.X.; Zhang, W.M.; Cheng, X.Y.; Chen, W.F. Effects of straw and biochar addition on soil nitrogen, carbon, and super rice yield in cold waterlogged paddy soils of North China. J. Integr. Agric. 2017, 16, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Wiedner, K.; Seelig, S.; Schmidt, H.; Gerber, H. Biochar organic fertilizers from natural resources as substitute for mineral fertilizers. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, A.; Lehmann, J. Comparison of wet-digestion and dry-ashing methods for total elemental analysis of biochar. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2012, 43, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhejiang Weather. Available online: http://zj.weather.com.cn (accessed on 1 February 2018).

- Cabangon, R.J.; Tuong, T.P.; Castillo, E.G.; Bao, L.X.; Lu, G.; Wang, G.; Cui, Y.; Bouman, B.A.; Li, Y.; Chen, C. Effect of irrigation method and N-fertilizer management on rice yield, water productivity and nutrient-use efficiencies in typical lowland rice conditions in China. Paddy Water Environ. 2004, 2, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.A.; Mullins, C.E. Soil and Environmental Analysis: Physical Methods, 2nd ed.; Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, H.D. Cation Exchange Capacity. In Methods of Soil Analysis; ASA: Madison, WI, USA, 1965; pp. 891–901. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio, V.C.; De Gerónimo, E.; Marino, D.; Primost, J.; Carriquiriborde, P.; Costa, J.L. Environmental fate of glyphosate and aminomethylphosphonic acid in surface waters and soil of agricultural basins. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1866–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, D. Changes in pH, CEC and exchangeable acidity of some forest soils in southern China during the last 32–35 years. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1998, 108, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.K. Methods of Soil and Agro-Chemical Analysis; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, R.S. Organic matter characterization. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 1011–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, R.H.; Kurtz, L.T. Determination of total, organic, and available forms of phosphorus in soils. Soil Sci. 1945, 59, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, S.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, X.; Fu, Y.; Jia, L. The earthworm Eisenia fetida can help desalinate a coastal saline soil in Tianjin, North China. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e144709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, R.L.; Sheard, R.W.; Moyer, J.R. Comparison of conventional and automated procedures for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium analysis of plant material using a single digestion. Agron. J. 1967, 59, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Xin, X.; Hao, X. How different long-term fertilization strategies influence crop yield and soil properties in a maize field in the North China Plain. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2013, 176, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Ye, L.L.; Wang, C.H.; Zhou, H.; Sun, B. Temperature-and duration-dependent rice straw-derived biochar: Characteristics and its effects on soil properties of an Ultisol in southern China. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 112, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Yang, X.; Shen, J.; Robinson, B.; Huang, H.; Liu, D.; Bolan, N.; Pei, J.; Wang, H. Effect of bamboo and rice straw biochars on the bioavailability of Cd, Cu, Pb and Zn to Sedum plumbizincicola. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 191, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintala, R.; Mollinedo, J.; Schumacher, T.E.; Malo, D.D.; Julson, J.L. Effect of biochar on chemical properties of acidic soil. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2014, 60, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Xu, R. The amelioration effects of low temperature biochar generated from nine crop residues on an acidic Ultisol. Soil Use Manag. 2015, 27, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, S.; She, D.; Geng, Z.; Gao, H. Effects of biochar on soil and fertilizer and future research. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2011, 27, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, C.J.; Fitzgerald, J.D.; Hipps, N.A. Potential mechanisms for achieving agricultural benefits from biochar application to temperate soils: A review. Plant Soil 2010, 337, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.M.; Busscher, W.J.; Laird, D.L.; Ahmedna, M.; Watts, D.W.; Niandou, M.A.S. Impact of biochar amendment on fertility of a southeastern Coastal Plain soil. Soil Sci. 2009, 174, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.Q.; Guppy, C.; Moody, P.; Gilkes, R.J.; Prakongkep, N. Effect of P and Si amendment on the charge characteristics and management of a Geric soil. In Proceedings of the 19th World Congress of Soil Science: Soil Solutions for a Changing World, Brisbane, Australia, 1–6 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Jiang, C.; Wu, M. Soil N transformation and microbial community structure as affected by adding biochar to a paddy soil of subtropical China. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Bian, R.; Pan, G.; Cui, L.; Hussain, Q.; Li, L.; Zheng, J.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, X. Effects of biochar amendment on soil quality, crop yield and greenhouse gas emission in a Chinese rice paddy: A field study of 2 consecutive rice growing cycles. Field Crop. Res. 2012, 127, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, F.; He, C.; Zhong, S.; Li, Y.; Lin, X. Effects of phosphorus fertilizer on phosphorus content, photosynthesis characters and yield of rice in cold waterlogged paddy field. J. Trop. Subtrop. Bot. 2016, 24, 553–558. [Google Scholar]

- Ierna, A.; Mauro, R.P.; Mauromicale, G. Improved yield and nutrient efficiency in two globe artichoke genotypes by balancing nitrogen and phosphorus supply. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; He, P.; Zhao, S.; Li, W.; Xie, J.; Hou, Y.; Grant, C.A.; Zhou, W.; Jin, J. Impact of nitrogen rate on maize yield and nitrogen use efficiencies in northeast China. Agron. J. 2014, 107, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, C.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, L.; Feng, C.; Guo, W.; Peng, Y. Responses of phosphorus use efficiency, grain yield, and quality to phosphorus application amount of weak-gluten wheat. J. Integr. Agric. 2012, 11, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Muttaleb, A. Effect of potassium fertilization on yield and potassium nutrition of Boro rice in a wetland ecosystem of Bangladesh. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2016, 62, 1530–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Ye, Z.; Luo, A. Potassium internal use efficiency relative to growth vigor, potassium distribution, and carbohydrate allocation in rice genotypes. J. Plant Nutr. 2004, 27, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, L.A.; Harpole, W.S. Biochar and its effects on plant productivity and nutrient cycling: A meta-analysis. GCB Bioenergy 2013, 5, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y. Impacts of biochar addition on rice yield and soil properties in a cold waterlogged paddy for two crop seasons. Field Crop. Res. 2016, 191, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, S.; Verheijen, F.G.; Van Der Velde, M.; Bastos, A.C. A quantitative review of the effects of biochar application to soils on crop productivity using meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 144, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.H.; Scheer, C.; Rowlings, D.W.; Grace, P.R. Rice husk biochar and crop residue amendment in subtropical cropping soils: Effect on biomass production, nitrogen use efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2016, 52, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Solaiman, Z.M.; Blackwell, P.; Abbott, L.K.; Storer, P.; Krull, E.; Singh, B.; Joseph, S. Direct and residual effect of biochar application on mycorrhizal root colonisation, growth and nutrition of wheat. Soil Res. 2010, 48, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zwieten, L.; Kimber, S.; Morris, S.; Chan, K.Y.; Downie, A.; Rust, J.; Joseph, S.; Cowie, A. Effects of biochar from slow pyrolysis of papermill waste on agronomic performance and soil fertility. Plant Soil 2010, 327, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; He, X.; Geng, Z.; Zhang, W.; Gao, H. Effects of biochar on selected soil chemical properties and on wheat and millet yield. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 6534–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Lehmann, J.; Zech, W. Ameliorating physical and chemical properties of highly weathered soils in the tropics with charcoal-a review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2002, 35, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Li, G.; Lin, Q.; Zhao, X. Crop yield and soil properties in the first 3 years after biochar application to a calcareous soil. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graber, E.R.; Harel, Y.M.; Kolton, M.; Cytryn, E.; Silber, A.; David, D.R.; Tsechansky, L.; Borenshtein, M.; Elad, Y. Biochar impact on development and productivity of pepper and tomato grown in fertigated soilless media. Plant Soil 2010, 337, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, D.A.; Novak, J.M.; Collins, H.P.; Ippolito, J.A.; Karlen, D.L.; Lentz, R.D.; Sistani, K.R.; Spokas, K.; Pelt, R.S.V. Multi-year and multi-location soil quality and crop biomass yield responses to hardwood fast pyrolysis biochar. Geoderma 2017, 289, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.Y.; Xu, Z. Biochar: Nutrient properties and their enhancement. In Biochar for Environmental Management: Science and Technology; Lehmann, J., Joseph, S., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 67–84. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Dai, G.; Hou, S. Effects of biochar on chlorophyll fluorescence at full heading stage and yield components of rice. Crops 2016, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sohi, S.; Lopez-Capel, E.; Krull, E.; Bol, R. Biochar, Climate Change and Soil: A Review to Guide Future Research; CSIRO Land and Water Science Report 05/09; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Major, J.; Rondon, M.; Molina, D.; Riha, S.J.; Lehmann, J. Maize yield and nutrition during 4 years after biochar application to a Colombian savanna oxisol. Plant Soil 2010, 333, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Unit | Biochar | Soil |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 9.71 | 5.06 | |

| EC | μS cm−1 | 3547.87 | 99.86 |

| CEC | cmol kg−1 | nd | 7.48 |

| OM | g kg−1 | nd | 34.61 |

| TC | g kg−1 | 442.68 | nd |

| TH | g kg−1 | 9.42 | nd |

| TS | g kg−1 | 2.44 | nd |

| TN | g kg−1 | 6.35 | 1.63 |

| AN | mg kg−1 | nd | 122.41 |

| TP | g kg−1 | 0.92 | nd |

| AP | mg kg−1 | nd | 5.98 |

| TK | g kg−1 | 28.15 | nd |

| AK | mg kg−1 | nd | 42.80 |

| Treatment | N | P2O5 | K2O | Biochar |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg ha−1) | (kg ha−1) | (kg ha−1) | (t ha−1) | |

| N1P1B0 | 120.0 | 37.5 | 67.5 | 0 |

| N1P1B1 | 120.0 | 37.5 | 67.5 | 2.25 |

| N1P2B0 | 120.0 | 67.5 | 67.5 | 0 |

| N1P2B1 | 120.0 | 67.5 | 67.5 | 2.25 |

| N2P1B0 | 180.0 | 37.5 | 67.5 | 0 |

| N2P1B1 | 180.0 | 37.5 | 67.5 | 2.25 |

| N2P2B0 (Farmers’ fertilization practice) | 180.0 | 67.5 | 67.5 | 0 |

| N2P2B1 | 180.0 | 67.5 | 67.5 | 2.25 |

| Treatment | Yield | Effective Panicles | Grains Per Panicle | Filled Grain Percentage | Thousand-Grain Weight | Harvest Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (t ha−1) | (×106 ha−1) | (%) | (g) | (%) | ||

| N1P1B0 | 7.5 ab | 3.08 a | 126.9 ab | 64.7 ab | 26.0 ab | 45.7 a |

| N1P1B1 | 6.5 ab | 2.94 a | 126.6 ab | 62.9 ab | 26.2 a | 46.2 a |

| N1P2B0 | 7.8 ab | 2.97 a | 119.3 b | 64.1 ab | 25.9 ab | 45.5 a |

| N1P2B1 | 6.7 ab | 3.00 a | 119.1 b | 72.7 a | 25.9 ab | 48.8 a |

| N2P1B0 | 7.4 ab | 3.30 a | 126.6 ab | 63.8 ab | 25.9 ab | 47.5 a |

| N2P1B1 | 6.7 ab | 3.04 a | 119.5 ab | 61.9 ab | 25.5 ab | 46.3 a |

| N2P2B0 | 6.0 b | 3.24 a | 114.1 b | 58.4 b | 25.8 ab | 44.8 a |

| N2P2B1 | 8.0 a | 3.24 a | 137.3 a | 66.7 ab | 25.1 b | 47.0 a |

| Treatment | Concentration (%) | Uptake (kg ha−1) | Internal Use Efficiency | Partial Factor Productivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain | Straw | Grain | Straw | Total | (kg kg−1) | (kg kg−1) | |

| N1P1B0 | 1.00 a | 0.54 a | 89.6 ab | 43.3 a | 132.9 ab | 67.6 a | 73.3 ab |

| N1P1B1 | 1.03 a | 0.56 a | 86.7 ab | 44.2 a | 130.8 ab | 65.8 a | 69.9 ab |

| N1P2B0 | 0.98 a | 0.50 a | 86.3 ab | 39.0 a | 125.2 ab | 69.7 a | 72.9 ab |

| N1P2B1 | 1.01 a | 0.50 a | 97.3 ab | 40.7 a | 138.1 ab | 69.7 a | 80.1 a |

| N2P1B0 | 1.02 a | 0.60 a | 91.4 ab | 42.9 a | 134.3 ab | 66.6 a | 50.1 c |

| N2P1B1 | 0.91 a | 0.51 a | 77.7 b | 38.4 a | 116.1 b | 74.1 a | 47.4 c |

| N2P2B0 | 0.99 a | 0.61 a | 87.4 ab | 45.4 a | 132.9 ab | 66.5 a | 49.0 c |

| N2P2B1 | 0.98 a | 0.59 a | 110.0 a | 56.8 a | 166.8 a | 66.9 a | 62.6 bc |

| Treatment | Concentration (%) | Uptake (kg ha−1) | Internal Use Efficiency | Partial Factor Productivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain | Straw | Grain | Straw | Total | (kg kg−1) | (kg kg−1) | |

| N1P1B0 | 0.288 a | 0.105 abc | 25.2 a | 8.3 b | 33.6 ab | 261.6 b | 234.5 a |

| N1P1B1 | 0.263 ab | 0.098 abc | 22.2 a | 7.5 b | 29.7 b | 284.4 ab | 223.7 a |

| N1P2B0 | 0.271 ab | 0.108 ab | 23.8 a | 8.3 b | 32.1 ab | 270.2 ab | 129.6 b |

| N1P2B1 | 0.271 ab | 0.094 bc | 26.1 a | 7.7 b | 33.8 ab | 284.5 ab | 142.4 b |

| N2P1B0 | 0.266 ab | 0.093 c | 24.0 a | 6.7 b | 30.7 b | 292.8 a | 240.6 a |

| N2P1B1 | 0.268 ab | 0.096 bc | 23.2 a | 7.0 b | 30.2 b | 286.3 ab | 227.7 a |

| N2P2B0 | 0.257 b | 0.101 abc | 22.8 a | 7.6 b | 30.4 b | 291.0 ab | 130.8 b |

| N2P2B1 | 0.256 b | 0.113 a | 29.1 a | 11.0 a | 40.1 a | 281.7 ab | 167.0 b |

| Treatment | Concentration (%) | Uptake (kg ha−1) | Internal Use Efficiency | Partial Factor Productivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain | Straw | Grain | Straw | Total | (kg kg−1) | (kg kg−1) | |

| N1P1B0 | 0.184 b | 1.33 ab | 16.16 b | 117.8 ab | 134.0 ab | 65.9 ab | 130.3 b |

| N1P1B1 | 0.188 ab | 1.34 ab | 15.75 b | 113.8 b | 129.6 b | 66.1 ab | 124.3 b |

| N1P2B0 | 0.193 ab | 1.28 b | 17.04 ab | 112.3 b | 129.3 b | 68.4 a | 129.6 b |

| N1P2B1 | 0.200 ab | 1.39 ab | 19.34 ab | 136.0 ab | 155.3 ab | 63.1 ab | 142.4 ab |

| N2P1B0 | 0.190 ab | 1.34 ab | 17.06 ab | 121.7 ab | 138.8 ab | 65.4 ab | 133.7 ab |

| N2P1B1 | 0.184 b | 1.49 a | 15.84 b | 126.4 ab | 142.3 ab | 59.9 b | 126.4 b |

| N2P2B0 | 0.193 ab | 1.25 b | 17.11 ab | 110.6 b | 127.7 b | 69.5 a | 130.8 b |

| N2P2B1 | 0.202 a | 1.41 ab | 22.94 a | 161.6 a | 184.5 a | 62.2 ab | 167.0 a |

| Parameter | N1P1B0 | N1P1B1 | N1P2B0 | N1P2B1 | N2P1B0 | N2P1B1 | N2P2B0 | N2P2B1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEC (cmol kg−1) | 8.37 ab | 8.17 b | 8.97 ab | 9.37 a | 8.43 ab | 8.10 b | 8.73 ab | 8.37 ab |

| ECa (cmol kg−1) | 4.45 ab | 4.20 c | 4.65 a | 4.46 ab | 4.56 ab | 4.35 bc | 4.63 a | 4.56 ab |

| EMg (cmol kg−1) | 1.04 b | 0.95 c | 1.13 a | 0.99 bc | 1.03 bc | 1.00 bc | 1.13 a | 0.99 bc |

| ENa (cmol kg−1) | 0.13 a | 0.09 b | 0.11 ab | 0.11 ab | 0.13 a | 0.11 ab | 0.11 ab | 0.11 ab |

| EK (cmol kg−1) | 0.16 a | 0.18 a | 0.17 a | 0.20 a | 0.22 a | 0.15 a | 0.21 a | 0.16 a |

| EH (cmol kg−1) | 0.15 a | 0.11 a | 0.11 a | 0.15 a | 0.13 a | 0.12 a | 0.19 a | 0.18 a |

| EAl (cmol kg−1) | 0.58 a | 0.33 b | 0.51 ab | 0.45 ab | 0.54 a | 0.47 ab | 0.52 a | 0.53 a |

| EA (cmol kg−1) | 0.73 a | 0.45 b | 0.62 ab | 0.60 ab | 0.67 ab | 0.59 ab | 0.71 a | 0.70 ab |

| EBC (cmol kg−1) | 5.78 abc | 5.43 c | 6.07 a | 5.76 abc | 5.93 ab | 5.61 bc | 6.07 a | 5.81 ab |

| BS (%) | 70.1 a | 66.6 a | 67.7 a | 61.5 a | 70.4 a | 69.2 a | 69.6 a | 69.7 a |

| pH | 5.01 b | 5.23 a | 5.09 ab | 5.11 ab | 5.11 ab | 5.10 ab | 5.04 b | 5.16 ab |

| EC (μS cm−1) | 133.4 a | 120.7 ab | 116.2 ab | 120.8 ab | 108.2 b | 118.1 ab | 111.2 ab | 121.4 ab |

| OM (g kg−1) | 43.7 a | 38.7 b | 43.1 ab | 43.8 a | 42.2 ab | 43.4 ab | 44.3 a | 44.0 a |

| TN (g kg−1) | 2.11 ab | 1.79 c | 1.86 bc | 2.15 a | 2.06 abc | 2.06 abc | 2.13 ab | 2.05 abc |

| AN (mg kg−1) | 168.9 a | 154.9 b | 167.1 ab | 172.2 a | 170.1 a | 173.8 a | 167.3 ab | 165.2 ab |

| AP (mg kg−1) | 5.0 ab | 4.5 b | 5.5 ab | 6.5 a | 5.2 ab | 4.7 b | 5.6 ab | 6.6 a |

| AK (mg kg−1) | 71.5 abcd | 51.7 d | 81.1 ab | 87.8 a | 58.8 cd | 65.8 bcd | 58.8 cd | 72.6 abc |

| Parameter | Source | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P | B | N × B | P × B | N × P × B | |

| PFPN | ** | |||||

| SPC | * | |||||

| SPU | * | * | ||||

| PFPP | ** | |||||

| GKC | * | |||||

| SKC | * | |||||

| IEK | * | |||||

| CEC | * | |||||

| ECa | ** | ** | ||||

| EMg | * | ** | * | |||

| EAl | * | |||||

| EBC | * | ** | ||||

| pH | * | |||||

| TN | * | |||||

| AP | ** | |||||

| AK | * | |||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Si, L.; Xie, Y.; Ma, Q.; Wu, L. The Short-Term Effects of Rice Straw Biochar, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizer on Rice Yield and Soil Properties in a Cold Waterlogged Paddy Field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020537

Si L, Xie Y, Ma Q, Wu L. The Short-Term Effects of Rice Straw Biochar, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizer on Rice Yield and Soil Properties in a Cold Waterlogged Paddy Field. Sustainability. 2018; 10(2):537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020537

Chicago/Turabian StyleSi, Linlin, Yinan Xie, Qingxu Ma, and Lianghuan Wu. 2018. "The Short-Term Effects of Rice Straw Biochar, Nitrogen and Phosphorus Fertilizer on Rice Yield and Soil Properties in a Cold Waterlogged Paddy Field" Sustainability 10, no. 2: 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020537