A Social–Ecological Systems Framework as a Tool for Understanding the Effectiveness of Biosphere Reserve Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Biosphere Reserves and Social–Ecological Systems Management and Governance

1.2. Social–Ecological Systems Frameworks and Biodiversity Conservation

1.3. Study Goals

- (i)

- Provide a more comprehensive understanding of factors related to biosphere reserve management effectiveness and;

- (ii)

- Contribute to a better understanding of factors, which are important for the integrated management of social–ecological systems and the conservation of biodiversity.

2. Materials and Methods

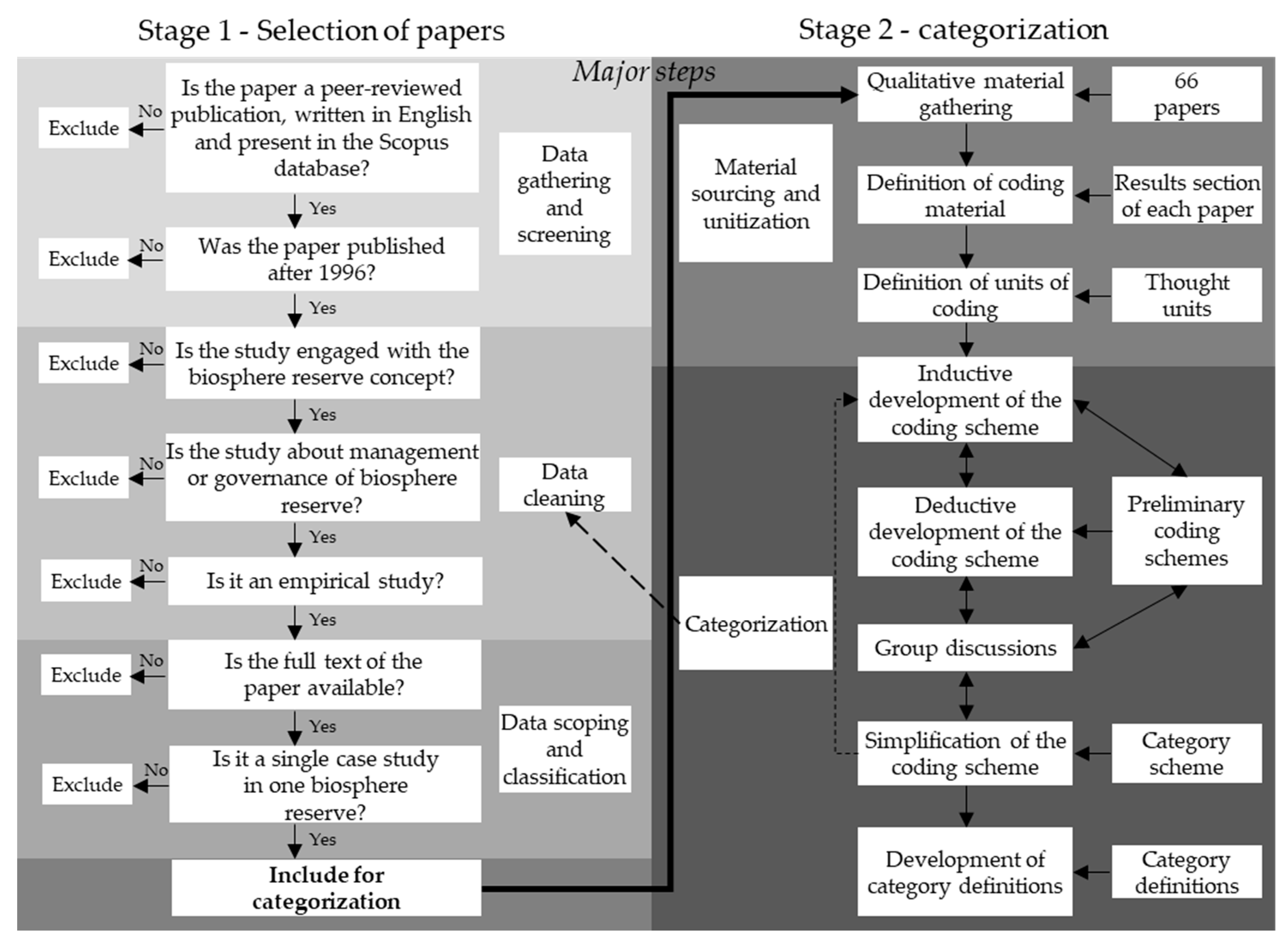

2.1. Paper Selection

2.2. Development of the Categories

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Influencing Biosphere Reserve Management Effectiveness

4.2. Biosphere Reserve Framework and Social–Ecological System Frameworks

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Author(s) | Title | Journal, Number (Issue), Pages | Year | DOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alonso-Yañez, G. and Davidsen, C. | Conservation science policies versus scientific practice: evidence from a Mexican biosphere reserve | Human Ecology Review, 20(2), 3–30 | 2014 | http://doi.org/http://www.jstor.org/stable/24707624 |

| Alonso-Yanez, G., Thumlert, K., and de Castell, S. | Re-mapping integrative conservation: (Dis) coordinate participation in a biosphere reserve in Mexico | Conservation and Society, 14(2), 134–145. | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.186335 |

| Azcárate, M. C. | Contentious hotspots: ecotourism and the restructuring of place at the Biosphere Reserve Ria Celestun (Yucatan, Mexico) | Tourist Studies, 10(2), 99–116 | 2010 | http://doi.org/10.1177/1468797611403033 |

| Behnen, T. | The man from the biosphere—exploring the interaction between a protected cultural landscape and its residents by quantitative interviews: the case of the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Rhön, Germany | Eco. Mont, 3(1), 5–10. | 2011 | http://doi.org/10.1553/eco.mont-3-1s5 |

| Boja, V., and Popescu, I. | Social ecology in the Danube Delta: theory and practice | Lakes and Reservoirs: Research and Management, 5(2), 125–131 | 2000 | http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1770.2000.00107.x |

| Brenner, L., and Job, H. | Actor-oriented management of protected areas and ecotourism in Mexico | Journal of Latin American Geography, 5(2), 7–27 | 2006 | http://doi.org/10.1353/lag.2006.0019 |

| Catalán, A. K. R. | The Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve: an exemplary participative approach? | Environmental Development, 16, 90–103. | 2015 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2015.04.005 |

| Constantin, M. | On the ethnographic categorization of biodiversity in the Danube Delta “Biosphere Reserve” | Eastern European Countryside, 18(1), 49–60 | 2012 | http://doi.org/10.2478/v10130-012-0003-x |

| Devine, J. | Counterinsurgency ecotourism in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve | Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(6), 984–1001 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.1068/d13043p |

| Durand, L., Figueroa, F., and Trench, T. | Inclusion and exclusion in participation strategies in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, Chiapas, Mexico | Conservation and Society, 12(2), 175–189. | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.138420 |

| Durand, L., and Lazos, E. | The local perception of tropical deforestation and its relation to conservation policies in Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve, Mexico | Human Ecology, 36(3), 383–394 | 2008 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-008-9172-7 |

| Elgert, L. | Governing portable conservation and development landscapes: reconsidering evidence in the context of the Mbaracayú Biosphere Reserve | Evidence and Policy, 10(2), 205–222 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X13990327720607 |

| Fazito, M., Scott, M., and Russell, P. | The dynamics of tourism discourses and policy in Brazil | Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 1–17 | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.013 |

| Fu, B., Wang, K., Lu, Y., Liu, S., Ma, K., Chen, L., and Liu, G. | Entangling the complexity of protected area management: the case of Wolong Biosphere Reserve, Southwestern China | Environmental Management, 33(6), 788–798 | 2004 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-004-0043-8 |

| Gerritsen, P., and Wiersum, F. | Farmer and conventional perspectives on conservation in Western Mexico | Mountain Research and Development, 25(1), 30–36 | 2005 | http://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2005)025[0030:FACPOC]2.0.CO;2 |

| Grandia, L. | Raw hides: hegemony and cattle in Guatemala’s northern lowlands | Geoforum, 40(5), 720–731 | 2009 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.01.004 |

| Habibah, A., Er, A. C., Mushrifah, I., Hamzah, J., Sivapalan, S., Buang, A., … Sharifah Mastura, S. A. | Revitalizing ecotourism for a sustainable Tasik Chini Biosphere Reserve | Asian Social Science, 9(14), 70–85 | 2013 | http://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n14p70 |

| Hagan, K., and Williams, S. | Oceans of discourses: utilizing Q methodology for analyzing perceptions on marine biodiversity conservation in the Kogelberg Biosphere Reserve, South Africa | Frontiers in Marine Science, 3, 188. | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2016.00188 |

| Hahn, T. | Self-organized governance networks for ecosystem management: Who is accountable? | Ecology and Society, 16(2), 18 | 2011 | http://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04043-160218 |

| Hill, W., Byrne, J., and Pegas, F. de V. | The ecotourism-extraction nexus and its implications for the long-term sustainability of protected areas: what is being sustained and who decides? | Journal of Political Ecology, 23(1), 307–327 | 2016 | http://dx.doi.org/10.2458/v23i1.20219 |

| Hill, W., Byrne, J., and Pickering, C. | The ‘hollow-middle’: why positive community perceptions do not translate into pro-conservation behaviour in El Vizcaíno Biosphere Reserve, Mexico | International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services and Management, 11(2), 168–183 | 2015 | http://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2015.1036924 |

| Hoffman, D. M. | Conch, cooperatives, and conflict: conservation and resistance in the Banco Chinchorro Biosphere Reserve | Conservation and Society, 12(2), 120–132 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.138408 |

| Humer-Gruber, A. | Farmers’ perceptions of a mountain biosphere reserve in Austria | Mountain Research and Development, 36(2), 153–161 | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-15-00054.1 |

| Kent, K., Sinclair, A. J., and Diduck, A. | Stakeholder engagement in sustainable adventure tourism development in the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India | International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 19(1), 89–100 | 2012 | http://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2011.595544 |

| Knaus, F., Bonnelame, L. K., and Siegrist, D. | The economic impact of labeled regional products: the experience of the UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Entlebuch | Mountain Research and Development, 37(1), 121–130 | 2017 | http://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-16-00067.1 |

| Kraus, F., Merlin, C., and Würzburg, H. J. | Biosphere reserves and their contribution to sustainable development | Zeitschrift Für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 58(2–3), 164–180. | 2014 | NA |

| Langholz, J. | Exploring the effects of alternative income opportunities on rainforest use: insights from Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve | Society and Natural Resources, 12(2), 139–149. | 1999 | http://doi.org/10.1080/089419299279803 |

| Lee, A. E. | Territorialisation, conservation, and neoliberalism in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve, Mexico | Conservation and Society, 12(2), 147–161 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.138413 |

| Li, W. | Community decision making—participation in development | Annals of Tourism Research, 33(1), 132–143 | 2006 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2005.07.003 |

| Liu, W., Vogt, C. A., Lupi, F., He, G., Ouyang, Z., and Liu, J. | Evolution of tourism in a flagship protected area of China | Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 24(2), 203–226 | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2015.1071380 |

| Lu, Y., Fu, B., Chen, L., Xu, J., and Qi, X. | The effectiveness of incentives in protected area management: an empirical analysis | International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology, 13(5), 409–417 | 2006 | http://doi.org/10.1080/13504500609469690 |

| Lyon, A., Hunter-Jones, P., and Warnaby, G. | Are we any closer to sustainable development? Listening to active stakeholder discourses of tourism development in the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve, South Africa | Tourism Management, 61, 234–247 | 2017 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.01.010 |

| Ma, Z., Li, B., Li, W., Han, N., Chen, J., and Watkinson, A. R. | Conflicts between biodiversity conservation and development in a biosphere reserve | Journal of Applied Ecology, 46(3), 527–535 | 2009 | http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2008.01528.x |

| Mahapatra, A. K., Tewari, D. D., and Baboo, B. | Displacement, deprivation and development: the impact of relocation on income and livelihood of tribes in Similipal Tiger and Biosphere Reserve, India | Environmental Management, 56(2), 420–432 | 2015 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-015-0507-z |

| Maikhuri, R. K., Nautiyal, S., Rao, K. S., Chandrasekhar, K., Gavali, R., and Saxena, K. G. | Analysis and resolution of protected area-people conflicts in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India | Environmental Conservation, 27(1), 43–53 | 2000 | http://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900000060 |

| Martinez-Reyes, J. E. | Beyond nature appropriation: towards post-development conservation in the Maya Forest | Conservation and Society, 12(2), 162–174 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.138417 |

| Mehring, M., and Stoll-Kleemann, S. | How effective is the buffer zone? Linking institutional processes with satellite images from a case study in the Lore Lindu Forest Biosphere Reserve, Indonesia | Ecology and Society, 16(4), 3 | 2011 | http://doi.org/10.5751/ES-04349-160403 |

| Méndez-Contreras, J., Dickinson, F., and Castillo-Burguete, T. | Community member viewpoints on the Ría Celestún Biosphere Reserve, Yucatan, Mexico: suggestions for improving the community/natural protected area relationship | Human Ecology, 36(1), 111–123 | 2008 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-007-9135-4 |

| Mollett, S. | Está listo (Are you ready)? Gender, race and land registration in the Río Plátano Biosphere Reserve | Gender, Place and Culture, 17(3), 357–375 | 2010 | http://doi.org/10.1080/09663691003737629 |

| Monterroso, I., and Barry, D. | Legitimacy of forest rights: the underpinnings of the forest tenure reform in the protected areas of Petén, Guatemala | Conservation and Society, 10(2), 136–150 | 2012 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.97486 |

| Nautiyal, S., and Nidamanuri, R. R. | Conserving biodiversity in protected area of biodiversity hotspot in India: a case study | International Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 36(2–3), 195–200 | 2010 | NA |

| Olson, E. A. | Notions of rationality and value production in ecotourism: examples from a Mexican biosphere reserve | Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(2), 215–233 | 2012 | http://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.610509 |

| Pfueller, S. L. | Role of bioregionalism in Bookmark Biosphere Reserve, Australia | Environmental Conservation, 35(2), 173–186 | 2008 | http://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892908004839 |

| Pulido, M. T., and Cuevas-Cardona, C. | Cactus nurseries and conservation in a biosphere reserve in Mexico | Ethnobiology Letters, 4, 96–104 | 2013 | http://dx.doi.org/10.14237/ebl.4.2013.58 |

| Rao, K. S., Nautiyal, S., Maikhuri, R. K., and Saxena, K. G. | Local peoples’ knowledge, aptitude and perceptions of planning and management issues in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India | Environmental Management, 31(2), 168–181 | 2003 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-002-2830-4 |

| Richardson, T. | On the limits of liberalism in participatory environmental governance: conflict and conservation in Ukraine’s Danube Delta | Development and Change, 46(3), 415–441 | 2015 | http://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12156 |

| Ruíz-López, D. M., Aragón-Noriega, A. E., Luna-Gonzalez, A., and Gonzalez-Ocampo, H. A. | Applying fuzzy logic to assess human perception in relation to conservation plan efficiency measures within a biosphere reserve | Ambio, 41(5), 467–478 | 2012 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-012-0252-y |

| Silori, C. S. | Socio-economic and ecological consequences of the ban on adventure tourism in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, western Himalaya | Biodiversity and Conservation, 13(12), 2237–2252 | 2004 | http://doi.org/10.1023/B:BIOC.0000047922.06495.27 |

| Silori, C. S. | Perception of local people towards conservation of forest resources in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, north-western Himalaya, India | Biodiversity and Conservation, 16(1), 211–222 | 2007 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-006-9116-8 |

| Singh, R. B., Mal, S., and Kala, C. P. | Community responses to mountain tourism: a case in Bhyundar Valley, Indian Himalaya | Journal of Mountain Science, 6(4), 394–404 | 2009 | http://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-009-1054-y |

| Smith, A. N. | Dilemmas of sustainability in Cocopah Territory: an exercise of applied visual anthropology in the Colorado River Delta | Human Organization, 75(2), 129–140 | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.17730/0018-7259-75.2.129 |

| Sodikoff, G. | The low-wage conservationist: biodiversity and perversities of value in Madagascar | American Anthropologist, 111(4), 443–455 | 2009 | http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01154.x |

| Solberg, M. | Patronage, contextual flexibility, and organisational innovation in Lebanese protected areas management | Conservation and Society, 12(3), 268–279 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.145138 |

| Steinberg, M., Taylor, M., and Kinney, K. | The El Cielo Biosphere Reserve: forest cover changes and conservation attitudes in an important neotropical region | The Professional Geographer, 66(3), 403–411 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2013.799994 |

| Sundberg, J. | Strategies for authenticity, space, and place in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Petén, Guatemala | Yearbook. Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers, 24, 85–96 | 1998 | http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17506200710779521 |

| Sundberg, J. | Conservation as a site for democratization in Latin America: exploring the contradictions in Guatemala | Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 27(53), 73–103 | 2002 | http://doi.org/10.1080/08263663.2002.10816815 |

| Sundberg, J. | Conservation and democratization: constituting citizenship in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala | Political Geography, 22(7), 715–740 | 2003 | http://doi.org/10.1016/S0962-6298(03)00076-3 |

| Sundberg, J. | Identities in the making: conservation, gender and race in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Guatemala | Gender, Place and Culture, 11(1), 43–66 | 2004 | http://doi.org/10.1080/0966369042000188549 |

| Sundberg, J. | Conservation encounters: transculturation in the “contact zones” of empire | Cultural Geographies, 13(2), 239–265 | 2006 | http://doi.org/10.1191/1474474005eu337oa |

| Sylvester, O., Segura, A. G., and Davidson-Hunt, I. J. | The protection of forest biodiversity can conflict with food access for indigenous people | Conservation and Society, 14(3), 279–290 | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.191157 |

| Trillo-Santamaría, J.-M., and Paül, V. | Transboundary protected areas as ideal tools? Analyzing the Gerês-Xurés Transboundary Biosphere Reserve | Land Use Policy, 52, 454–463 | 2016 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.019 |

| Vaidianu, N., Tofan, L., Braghina, C., and Schvab, A. | Legal and institutional framework for integrated governance in a biosphere reserve | Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology, 16(3), 1149–1159 | 2015 | NA |

| Velez, M., Adlerstein, S., and Wondolleck, J. | Fishers’ perceptions, facilitating factors and challenges of community-based no-take zones in the Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve, Quintana Roo, Mexico | Marine Policy, 45, 171–181 | 2014 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.12.003 |

| Xu, J., Chen, L., Lu, Y., and Fu, B. | Local people’s perceptions as decision support for protected area management in Wolong Biosphere Reserve, China | Journal of Environmental Management, 78(4), 362–372 | 2006 | http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2005.05.003 |

| Young, E. | Local people and conservation in Mexico’s El Vizcaino Biosphere Reserve | The Geographical Review, 89(3), 364–390 | 1999 | http://doi.org/10.2307/216156 |

| Yuan, J., Dai, L., and Wang, Q. | State-led ecotourism development and nature conservation: a case study of the Changbai Mountain Biosphere Reserve, China | Ecology and Society, 13(2), 55 | 2008 | http://doi.org/10.5751/ES-02645-130255 |

Appendix D

| Category | Definition |

|---|---|

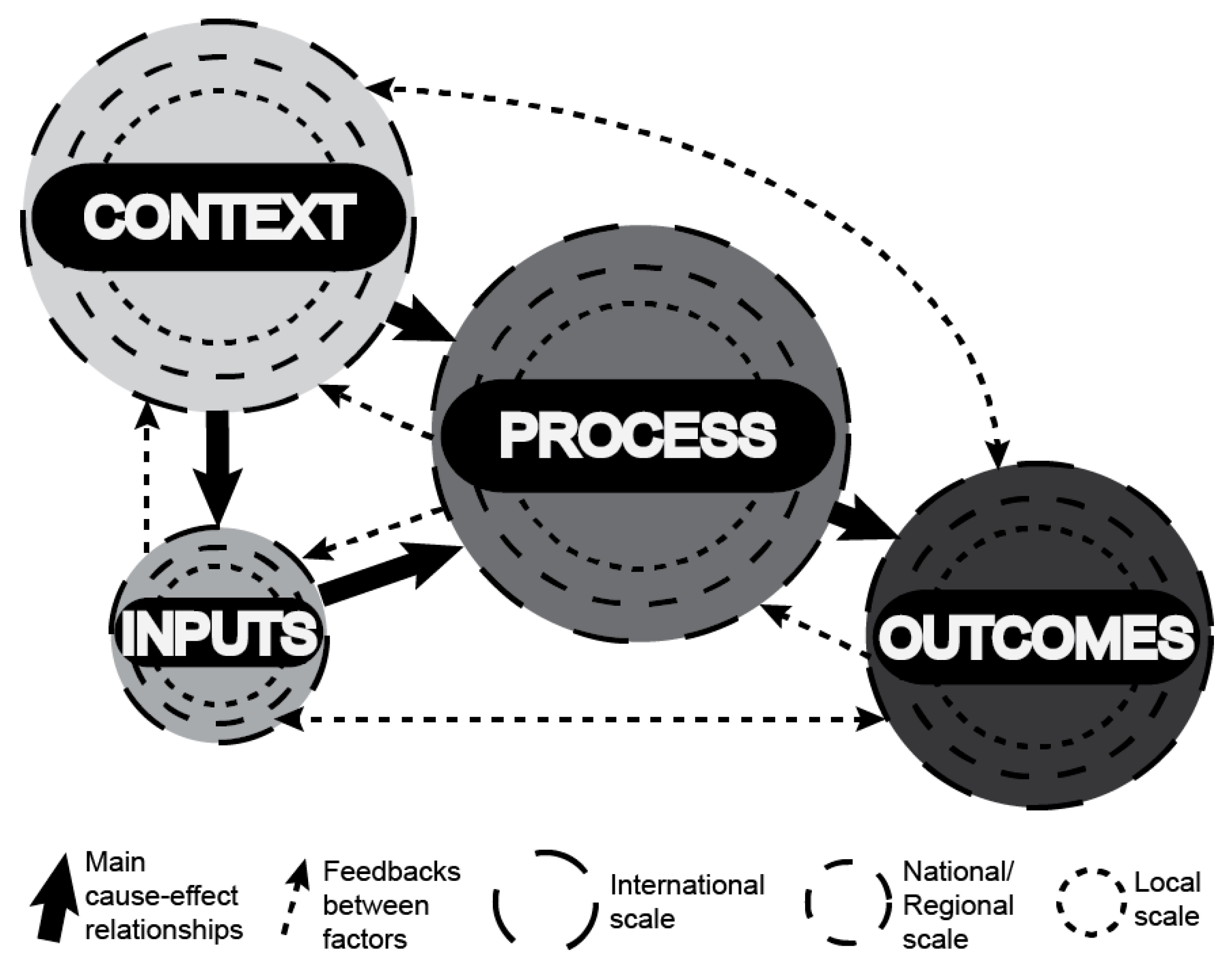

| Context (C) | Place-based and multiscale features of which the presence or absence shape the settings where BRs are implemented. They can have a direct or indirect influence in the process, the inputs or the outcomes. The context is not about the BR implementation (process) but about the characteristics of the settings, independently of the BR. |

| Inputs (I) | What was invested in the process? Material and immaterial support or opposition at different scales. |

| Process (P) | How is management/governance being conducted? The actions and mechanisms by which management and governance takes place. |

| Outcomes (O) | Impacts and benefits in social and ecological systems, that followed the implementation of the process. |

| Sub-Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| C1 Regulations—formal rules | The written rules, i.e., legislation, regulatory structure, land tenure. This does not mean that they are the rules in use, since actors can ignore them and use informal rules. Legislatures, regulatory agencies and courts usually determine the formal rules in place [69]. |

| C2 Informal institutions and culture | Rules that are self-organized by informal gatherings, appropriation teams or private associations [69]. It also includes norms, i.e., shared perceptions/beliefs among a social group which define the proper or improper behaviors. They are closely related to cultural prescriptions and, therefore, issues related to culture are also included here [30]. Trust-reciprocity/social capital is also associated with existing social norms. Here only the social context is observed—if the use of natural resources is considered to be part of the culture, this is included in the sub-category “Use of natural resources cultural purposes” (C11). |

| C3 Power issues | Power is related to the “ability to force people to do things they would not independently choose to do” [70]. Power issues are referred to by the term “power” and/or linked with the identification of some group with power (e.g., men) and a group without power (e.g., women), in a defined context. |

| C4 Organizations | An organization refer to a group of people which are bounded to achieve some common objective, including political bodies, economic bodies, social bodies and education bodies [71]. All aspects related to the organizations in place—organizations structure, inter-organizations relationships, organizations goals, and other organization features, such as if organizations are corrupt, are included here. This includes also factors related to the ability, or lack of ability, of organizations to meet their goals, e.g., lack of funding, human resources or human resources without skills. |

| C5 Historical factors | Historical factors are events that occurred in the past which still impact how things happen today, e.g., previous communist regime, colonization. If the event is very recent or is still happening, it is included in one of the other context sub-categories (possibly “Socio-economic attributes”—C8). |

| C6 Time | Do time restrictions influence management? E.g., the need to do something fast; time restrictions influenced the participatory processes. |

| C7 Economy and politics | The economic and political systems in place—markets, financial crises, regimes (democratic vs. autocratic), political philosophies (liberalism vs. non-liberalism). |

| C8 Socio-economic attributes | Includes social and economic phenomena such as: (1) social phenomena, i.e. migrations, conflicts; political phenomena, i.e. the fall of a president; illegal activities, i.e. the illegal exploitation of natural resources, human trafficking, drugs, etc.; (2) general attributes of the society: unemployment, poverty, population size, etc.; (3) infrastructure in place—access to water or electricity services (not information infrastructure); (4) specific characteristics of the communities, e.g., level of education, skills, resources. |

| C9 Information related | Existing communication infrastructure and the quality of information sources, such as media; e.g., if there is access to internet or telephone, or if local media report news about a BR. |

| C10 Use of natural resources for livelihoods | The exploitation of natural resources is reported to be important for livelihoods; i.e., fishing, logging or subsistence agriculture is fundamental to provide food, shelter or medicinal plants. This requires the extraction of the natural resource. |

| C11 Use of natural resources for cultural purposes | Natural resources are reported to be important for cultural purposes, e.g., recreation and religion. Includes both extractive and non-extractive use of natural resources for cultural purposes. Therefore, if it is reported that the extractive use of natural resources (e.g., fishing) is part of a community culture, it is also included here. |

| C12 Impacts on natural resources | Includes references of impacts on natural resources, e.g., less fish, pollution, etc. |

| C13 Human–wildlife conflicts | Conflicts between people and wildlife, e.g., wildlife attacks on livestock or humans. |

| C14 Cultural landscape | The historical/traditional use of the landscape makes it dependent on these human–nature interactions. This dependency is reported. |

| C15 Conservationist value | The species or ecosystems in place are reported to have conservationist value, e.g., species are highly endangered or the presence of a unique habitat. |

| C16 Bio-physical attributes | Bio-physical attributes, such as altitude or climate, including the occurrence of extreme weather events, or ecological disasters such as pests. |

| C17 Resource mobility | The presence of resources with high mobility which influence management/governance/outcomes, e.g., migratory species. |

| Sub-Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| I1 Attitudes | According to Ajzen and Fishbei [72] “An attitude can be defined as a positive or negative evaluation of an object or quality”. We included manifested attitudes, i.e., the negative or positive evaluations people express about the process, and not behaviors (e.g. because people don’t like the management body (attitude), they do not go to the meetings (behavior, in this case, is a lack of non-material support)). |

| I2 Beliefs | Beliefs underlie “a person’s attitudes and subjective norms, and they ultimately determine intentions and behavior” [72]. We are coding beliefs, including perceived benefits or impacts, values and worldviews, which explain why people have a determined attitude or behavior. |

| I3 Funding and material support/opposition | Includes concrete assistance, such as funding and performing assigned work for others. Opposition do not require active opposition, i.e., when lack of support/funding was reported to have some important effect, it was also included as “passive opposition”. |

| I4 Non-material support/opposition | Includes all forms of support/opposition that are not tangible goods and services, including emotional (caring, empathy, love and trust), informational support (provision of information for problem-solving) and appraisal/affirmational support [73]. We relate the appraisal/affirmational support/opposition with lobbying for or against someone else’s cause. Actors can influence process policies in many different ways, including attending and organizing protests or other social movements, participating or not in public meetings on the subject, influencing the media, etc. [74], by facilitating connections between different governmental organizations and influencing decisions. Opposition do not require active opposition, i.e., when lack of support was reported to have some important effect it was also included as “passive opposition”. |

| I5 Type of knowledge | This includes scientific knowledge but also experiential knowledge, i.e., local ecological knowledge, indigenous knowledge and traditional knowledge [7]. |

| Sub-Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| P1 Process scale | Is the paper about the management/governance of the BR (management/governance body), task/project management/governance, or both? |

| P2 Spatial design | Spatial design of the area where the process takes place. Includes characteristics such as the total area, zoning and location. |

| P3 Process initiation | Includes aspects related to how the process was initiated: top-down—the initiative came from the “top” and was imposed in the local settings; participatory—the initiative came from the “top” but its implementation was discussed with local communities since the beginning; bottom-up—self-mobilization of the local communities. |

| P4 Public participation | Is civil society participating in the BR management/implementation? Includes whether civil society is consulted for BR management and/or projects; participate in BR activities (e.g., as staff) or participate in BR management (e.g., through access to the discussions, dialogue, or influencing BR decisions (adapted from [75,76]). |

| P5 Participatory processes | Design and organization of participatory meetings, including pre-, during, and post-meeting settings; who is included, balance of power and participatory exclusions [75]. Pre-meeting settings include who participates in the agenda setting, if the information is available to everyone before the meeting and how are invitations to the meeting disseminated; during the meeting settings include how are decisions made, if the information was provided in an adequate format, if there are mechanisms to ensure that everyone has time to speak; post-meeting settings include if there are mechanisms to monitor the implementation of the decisions [51]. |

| P6 Management body | Is there a proper (formal) BR management body in place? What is its degree of centralization? References about the centralization of decision making (e.g., the managers offices are very far away from the BR). What is the structure of the management body—who is included/excluded? How many actors? Power balance. |

| P7 Coordination and leadership | This includes features related to the quality of the management—bad management is characterized by a lack of functionality, mismanagement and lack of coordination of the activities inside the BR. Its related with lack of collaboration, cooperation, communication and clear mandates for BR management. Characteristics of the decision-makers, such as leadership, are also included. |

| P8 Institutions for management | This includes the use of formal and/or informal institutions. Formal rules are the written rules, i.e., legislation, regulatory structure, etc. Informal institutions include traditions, customs, beliefs and social networks. |

| P9 Material investments and infrastructure | This includes the development of infrastructure and acquisition of other tangible materials, such as vehicles. |

| P10 Human resources related | This includes hiring human resources as staff or managers, and their working conditions—i.e., references to wages, full-time vs. part-time work, seasonality, etc. |

| P11 Conservation and habitat management | Includes active management of habitats and species in order to achieve conservation goals: habitat restauration through e.g., revegetation, species reintroduction, invasive species control, etc. |

| P12 Restrictions | Decrease environmental harms through restrictions: prohibitions, restrictions, taxes, fees (e.g., park entry), charges, quotas, compensations for environmental damages (e.g., biodiversity offsets), etc. |

| P13 Enforcement and control | Enforcement and control of natural resource use and development. Monitoring of activities which harm the environment and sanctioning (e.g., park patrols). |

| P14 Incentives | Incentives refer to the reduction of environmental harms through the promotion of more environmentally friendly behaviors, e.g., payments for ecosystems services, tax breaks, compensation for wildlife damage, subsidies, forest concessions; promotion of markets for green goods and services by stimulating producers adopting environmentally friendly methods, and consumers buying green goods and services (e.g., certification). It includes all the activities related to sustainable development, such as such as ecotourism, sustainable agriculture, etc. |

| P15 Economic development | This includes the development of initiatives which are mainly related to economic goals, e.g., mining. Fishing and grazing are only considered if some action was made in order to promote these kinds of activities, e.g., revert previous restrictions on natural resource use. |

| P16 Research and monitoring | Research and monitoring of natural or social resources. |

| P17 Information and capacity building | This includes: (i) provision of training or consultancy; (ii) development of BR image and platforms with information about the BR or BR policies (website, radio programs, etc.); (iii) information materials, such as flyers and signage; (iv) provision of platforms for dialogue through the organization of participatory meetings and other networking opportunities (such as barbecues, cultural festivals); (v) collaboration, partnerships. |

| P18 Planning | Planning of processes at different levels (e.g., project or BR; BR management plan). Plans establish the vision, goals and strategies of the process. |

| Sub-Category | Definition |

|---|---|

| O1 Economic benefits | Reported increase of monetary wealth or employment; increase of business and industries productivity [77] as a result of management actions. |

| O2 Social benefits | Improvement of social infrastructure (schools, etc.); increase social capital by an increase of trust, cooperation and better communication; decrease in conflicts. |

| O3 Empowerment | Less powerful actors gain (or are given) increase control over their “lives and livelihoods”; if local communities are given the responsibility and decision making of management of their own resources [52]. |

| O4 Health benefits | Includes emotional (motivation, feeling of happiness, satisfaction, sense of live security) and other health related benefits. |

| O5 Learning | If, after some management/governance action (e.g., participatory processes, training, networking), some of the following occur: (i) there is a change in the strategies/actions, goals or governance mechanisms resulting from social interaction—social learning; (ii) there is a change in people’s and/or group perceptions or values—transformative communicative learning; (iii) acquisition of knowledge that is task-orientated/problem solving and aim to improve the performance of the current activity—transformative instrumental learning; (iv) knowledge that results from experience/learning-by-doing—experiential learning; (v) if the paper’s author report “learning” (adapted from [54]). |

| O6 Cultural benefits | Enhancement of cultural identity (cultural revitalization), preservation of traditional knowledge, access to livelihoods and recreation opportunities and promotion of traditional practices or customs [77]. |

| O7 Environmental benefits | Environmental benefits including an increase in species populations, recruitment of plants, resilience, decrease in overharvesting natural resources. |

| O8 Economic impacts | Reported decrease in monetary wealth or increase of unemployment; decrease of business and industry productivity [77] as a result of management/governance actions. |

| O9 Social impacts | Displacement; decreased social capital—lack of trust, communication and cooperation; occurrence of conflicts as a result of management/governance actions. |

| O10 Inequality | Uneven distribution of the benefits and costs of BR management/governance actions. |

| O11 Health impacts | Includes emotional (stress, frustration, dissatisfaction, insecurity) and other health-related impacts resulting from management/governance actions. |

| O12 Cultural impacts | Impacts of cultural identity, e.g., by separating people from their traditional livelihoods or culturally important sites and resources, erosion of traditional knowledge and other traditional practices or customs [77]. |

| O13 Environmental impacts | Environmental impacts including decreases in species population or distribution, overharvesting natural resources or decreases in resilience as a result of management/governance actions. |

Appendix E

References

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Dudley, N.; Jaeger, T.; Lassen, B.; Pathak Broome, N.; Phillips, A.; Sandwith, T. Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lausche, B. Guidelines for Protected Areas Legislation; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. MAB STRATEGY 2015-2025; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR). Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/biosphere-reserves (accessed on 12 June 2017).

- Batisse, M. Action Plan for biosphere reserves. Environ. Conserv. 1985, 12, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Biosphere Reserves—The Seville Strategy & the Statutory Framework of the World Network; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, L.; Lundholm, C. Learning for resilience? Exploring learning opportunities in biosphere reserves. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I.; Montes, C.; Martín-López, B.; González, J.A.; García-Llorente, M.; Alcorlo, P.; Mora, M.R.G. Incorporating the social-ecological approach in protected areas in the Anthropocene. Bioscience 2014, 64, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Allen, C.R.; Ban, N.C.; Biggs, D.; Biggs, H.C.; Cumming, D.H.M.; De Vos, A.; Epstein, G.; Etienne, M.; Maciejewski, K.; et al. Understanding protected area resilience: A multi-scale, social-ecological approach. Ecol. Appl. 2015, 25, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berkes, F.; Colding, J.; Folke, C. Introduction. In Navigating Social-Ecological Systems Bulding Resilience for Complexity and Change; Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 1–29. ISBN 978-0-521-81592-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Johansson, K. Trust-building, knowledge generation and organizational innovations: The role of a bridging organization for adaptive comanagement of a wetland landscape around Kristianstad, Sweden. Hum. Ecol. 2006, 34, 573–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.F.; Park, J.J.; Bouamrane, M. Reporting progress on internationally designated sites: The periodic review of biosphere reserves. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Final Report of the Twenty-fifth Session of the ICC—MAB—SC-13/CONF.225/11; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hockings, M.; Stolton, S.; Leverington, F.; Dudley, N.; Courrau, J. Evaluating Effectiveness—A Framework for Assessing Management Effectiveness of Protected Areas, 2nd ed.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.G.; Egunyu, F. Management effectiveness in UNESCO Biosphere Reserves: Learning from Canadian periodic reviews. Environ. Sci. Policy 2013, 25, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertzky, M.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Multi-level discrepancies with sharing data on protected areas: What we have and what we need for the global village. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, L.; Duit, A.; Folke, C. Participation, adaptive co-management, and management performance in the World Network of Biosphere Reserves. World Dev. 2011, 39, 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Welp, M. Participatory and integrated management of biosphere reserves—Lessons from case studies and a global survey. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. 2008, 17, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cuong, C.; Dart, P.; Hockings, M. Biosphere reserves: Attributes for success. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-López, B.; Montes, C. Restoring the human capacity for conserving biodiversity: A social–ecological approach. Sustain. Sci. 2014, 10, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, N.C.; Mills, M.; Tam, J.; Hicks, C.C.; Klain, S.; Stoeckl, N.; Bottrill, M.C.; Levine, J.; Pressey, R.L.; Satterfield, T.; et al. A social-ecological approach to conservation planning: Embedding social considerations. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 11, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkes, F.; Folke, C. Linking social and ecological systems for resilience and sustainability. In Linking Social and Ecological Systems—Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience; Berkes, F., Folke, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 1–25. ISBN 0521591406. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.; Gardner, T.A.; Bennett, E.M.; Balvanera, P.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.; Daw, T.; Folke, C.; Hill, R.; Hughes, T.P.; et al. Advancing sustainability through mainstreaming a social-ecological systems perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cumming, G.S. The relevance and resilience of protected areas in the Anthropocene. Anthropocene 2015, 13, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, S.T.A.; Kolasa, J.; Jones, C.G. Ecological Understanding: The Nature of Theory and the Theory of Nature, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 9780125545228. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Cox, M.E. Moving beyond panaceas: A multi-tiered diagnostic approach for social-ecological analysis. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, C.; Hinkel, J.; Bots, P.; Claudia, P.-W. Comparison of frameworks for analyzing social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S. Spatial Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinnis, M.D.; Ostrom, E. Social-ecological system framework: Initial changes and continuing challenges. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Ostrom, E.; Stern, P.C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 2003, 302, 1907–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, P.C. Design principles for global commons: Natural resources and emerging technologies. Int. J. Commons 2011, 5, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Burger, J.; Field, C.B.; Norgaard, R.B.; Policansky, D. Revisiting the commons: Local lessons, global challenges. Science 1999, 284, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luederitz, C.; Meyer, M.; Abson, D.J.; Gralla, F.; Lang, D.J.; Rau, A.L.; von Wehrden, H. Systematic student-driven literature reviews in sustainability science—An effective way to merge research and teaching. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 119, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luederitz, C.; Brink, E.; Gralla, F.; Hermelingmeier, V.; Meyer, M.; Niven, L.; Panzer, L.; Partelow, S.; Rau, A.L.; Sasaki, R.; et al. A review of urban ecosystem services: Six key challenges for future research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2015, 14, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srnka, K.J.; Koeszegi, S.T. From words to numbers: How to transform qualitative data into meaningful quantitative results. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2007, 59, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. The case survey method and applications in political science. In Proceedings of the APSA 2009 Meeting, Toronto, ON, Canada, 3–6 September 2009; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences—A Practical Guide; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA; Oxford, UK; Carlton, Australia, 2006; ISBN 9781405121101. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Harlow, UK, 2009; ISBN 9780273716860. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. UNESCO—MAB Biosphere Reserves Directory. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/mabdb/br/brdir/directory/database.asp (accessed on 12 June 2017).

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; De La Vega-Leinert, A.C.; Schultz, L. The role of community participation in the effectiveness of UNESCO Biosphere Reserve management: Evidence and reflections from two parallel global surveys. Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G.W.; Bernard, H.R. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2003, 15, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo-Santamaría, J.-M.; Paül, V. Transboundary protected areas as ideal tools? Analyzing the Gerês-Xurés Transboundary Biosphere Reserve. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, J. Counterinsurgency ecotourism in Guatemala’s Maya Biosphere Reserve. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2014, 32, 984–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, A.; Hunter-Jones, P.; Warnaby, G. Are we any closer to sustainable development? Listening to active stakeholder discourses of tourism development in the Waterberg Biosphere Reserve, South Africa. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, J. Strategies for authenticity, space, and place in the Maya Biosphere Reserve, Petén, Guatemala. Year. Conf. Lat. Am. Geogr. 1998, 24, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maikhuri, R.K.; Nautiyal, S.; Rao, K.S.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Gavali, R.; Saxena, K.G. Analysis and resolution of protected area-people conflicts in Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve, India. Environ. Conserv. 2000, 27, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; Stoll-Kleemann, S. Opportunities and barriers in the implementation of protected area management: A qualitative meta-analysis of case studies from European protected areas. Geogr. J. 2011, 177, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, M.M. A road to tomorrow: Local organizing for a biosphere reserve. Environments 2004, 32, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Azcárate, M.C. Contentious hotspots: Ecotourism and the restructuring of place at the Biosphere Reserve Ria Celestun (Yucatan, Mexico). Tour. Stud. 2010, 10, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, L.; Figueroa, F.; Trench, T. Inclusion and exclusion in participation strategies in the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve, Chiapas, Mexico. Conserv. Soc. 2014, 12, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.A.; Holmes, G.; Harris, W.E.; Evans, K.L. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velez, M.; Adlerstein, S.; Wondolleck, J. Fishers’ perceptions, facilitating factors and challenges of community-based no-take zones in the Sian Ka’an Biosphere Reserve, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Mar. Policy 2014, 45, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T. Self-organized governance networks for ecosystem management: Who is accountable? Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, D.W.; Moser, S.C. Linking global and local scales: Dynamic assessment and management processes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2000, 10, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, G.S.; Cumming, D.H.M.; Redman, C.L. Scale mismatches in social-ecological systems: Causes, consequences, and solutions. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, A.; Ciocanea, C.M.; Manolache, S.; Rozylowicz, L. A network approach for understanding opportunities and barriers to effective public participation in the management of protected areas. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2018, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nita, A.; Rozylowicz, L.; Manolache, S.; CiocǍnea, C.M.; Miu, I.V.; Dan Popescu, V. Collaboration networks in applied conservation projects across Europe. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pool-Stanvliet, R.; Stoll-Kleemann, S.; Giliomee, J.H. Criteria for selection and evaluation of biosphere reserves in support of the UNESCO MAB programme in South Africa. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Baird, J.; Armitage, D.; Bodin, Ö.; Schultz, L. Diagnosing adaptive comanagement across multiple cases. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity for National and International Policy Makers; TEEB: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, G.S. Social-Ecological Systems in Transition. In Social-Ecological Systems in Transition; Sakai, S., Umetsu, C., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2014; pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-4-431-54909-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons—The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; ISBN 978-0-521-37101-8. [Google Scholar]

- Jax, K.; Barton, D.N.; Chan, K.M.A.; de Groot, R.; Doyle, U.; Eser, U.; Görg, C.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Griewald, Y.; Haber, W.; et al. Ecosystem services and ethics. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butchart, S.H.M.; Walpole, M.; Collen, B.; van Strien, A.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Almond, R.E.A.; Baillie, J.E.M.; Bomhard, B.; Brown, C.; Bruno, J.; Carpenter, K.E.; et al. Global biodiversity: Indicators of recent declines. Science 2010, 328, 1164–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, H.M.; Leadley, P.W.; Proença, V.; Alkemade, R.; Scharlemann, J.P.W.; Fernandez-Manjarrés, J.F.; Araújo, M.B.; Balvanera, P.; Biggs, R.; Cheung, W.W.L.; et al. Scenarios for global biodiversity in the 21st century. Science 2010, 330, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, H.E.; Farley, J. Ecological Economics Principles and Applications, 2nd ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-59726-681-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005; Volume 132, ISBN 0691122385. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. Indicators and Information Systems for Sustainable Development; The Sustainability Institute: Hartland, VT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbei, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980; ISBN 0-13-936443-9. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, C.P.H.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social support: A conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Black, J.S. Support for Environmental Protection—The Role of Moral Norms. Popul. Environ. 1986, 8, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, B. Participatory Exclusions, Community Forestry, and Gender: An Analysis for South Asia and a Conceptual Framework. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1623–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Frewer, L.J. A Typology of public engagement mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2005, 30, 251–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan-Hallam, M.; Bennett, N.J. Adaptive social impact management for conservation and environmental management. Conserv. Biol. 2017, 32, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Review Step | Procedure | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data gathering | Database search on Scopus using the defined search string. | Bibliographical information of 2499 potentially relevant papers |

| 2. Data screening | Screening of the data to define the inclusion criteria. Papers published before 1996 were excluded. | Data set reduced to 2286 potentially relevant papers |

| 3. Data cleaning | Screening the title, abstracts and keywords guided by the questions: (i) Is the study engaged with the biosphere reserve concept? (ii) Is the study about management or governance of biosphere reserves? Is the study useful to understand the factors influencing management and governance of biosphere reserves? (iii) Is it an empirical study? 10% of the papers were evaluated by two reviewers and the different decisions discussed. | Data set reduced to 186 potentially relevant papers |

| 4. Data scoping | Download of the potentially relevant papers. | Download of 177 papers (9 papers with no full-text access) |

| 5. Paper classification | Definition of the scale of analysis resulted in the exclusion of those studies with more than one case study. Further papers were excluded because they were not developed in UNESCO biosphere reserves or they didn’t comply with the criteria defined in step 3. | 66 case studies |

| 6. Categorization | “Thought units” were selected as the units of coding. The category scheme was developed through a backward and forward inductive–deductive approach, based on preliminary and recursive coding. | Category scheme with 4 categories and 53 sub-categories |

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Engagement of the study with the biosphere reserve concept | Studies performed in biosphere reserves, or that engage with them in some way, e.g., studies realized in adjacent areas, but which report implications for the biosphere reserve. |

| Link with management or governance of biosphere reserves | A paper was considered to be about management or governance of biosphere reserves if it reported on specific actions that were associated with the biosphere reserve’s decision-making body. Defining effectiveness against some pre-determined goals was not possible because the goals of the program are very broad (e.g., sustainable development) and different biosphere reserves have different, more tangible goals. Papers about why management or governance is performed in a specific way were also included. Besides that, we only selected papers about biosphere reserve management or governance, and not its designation, in order to exclude “paper biosphere reserves”, i.e., those where active management is not in place. |

| Empirical study | An empirical study includes primary or secondary data but not “analysis of analysis”, i.e., reviews or research synthesis [37]. A critical appraisal of the methods and results of the papers resulted in the elimination of those that do not present enough information for meaningful interpretation [38] and opinion papers. Studies using very different strategies (e.g., experiments, surveys, ethnographies) were included, in order to cover a diversity of inquiry belief systems or worldviews [39]. We acknowledge, however, our limitations in doing so, since reviewers bring with them their own research philosophies, which will influence not only their strategies and methods, but their perceptions on what is important or useful to consider [39]. |

| Context (C) | Process (P) | |

| “Institutions and organizations” | “Project and spatial dimension” | |

| C1 Regulations—formal rules | P1 Process scale | |

| C2 Informal institutions and culture | P2 Spatial design | |

| C3 Power issues | “Decision making” | |

| C4 Organizations | P3 Process initiation | |

| “Time related” | P4 Public participation | |

| C5 Historical factors | P5 Participatory processes | |

| C6 Time | P6 Management body | |

| “Socio-economic attributes” | P7 Coordination and leadership | |

| C7 Economy and politics | P8 Institutions for management | |

| C8 Socio-economic attributes | “Instruments” | |

| C9 Information related | P9 Material investments and infrastructure | |

| “Purpose of natural resources use” | P10 Human resources related | |

| C10 Use of natural resources for livelihoods | P11 Conservation and habitat management | |

| C11 Use of natural resources for cultural purposes | P12 Restrictions | |

| “Human-nature relationship” | P13 Enforcement and control | |

| C12 Impacts on natural resources | P14 Incentives | |

| C13 Human–wildlife conflicts | P15 Economic development | |

| C14 Cultural landscape | P16 Research and monitoring | |

| C15 Conservationist value | P17 Information and capacity building | |

| “Ecological context” | P18 Planning | |

| C16 Bio-physical attributes | ||

| C17 Resource mobility | ||

| Inputs (I) | Outcomes (O) | |

| “Attitudes and beliefs” | “Benefits” | “Impacts” |

| I1 Attitudes | O1 Economic | O8 Economic |

| I2 Beliefs | O2 Social | O9 Social |

| “Investments” | O3 Empowerment | O10 Inequality |

| I3 Funding and material support/opposition | O4 Health | O11 Health |

| I4 Non-material support/opposition | O5 Learning | O12 Cultural |

| I5 Type of knowledge | O6 Cultural | O13 Environmental |

| O7 Environmental | ||

| Aspect/Framework | Ostrom | Biosphere Reserves |

|---|---|---|

| Goal | Understand factors that affect the likelihood of self-organization for natural resource management | Understand factors that affect biosphere reserve management effectiveness |

| Scale | Small-scale, usually a common-pool resource (e.g., forest, fisheries, groundwater) | Local to international scales—some case studies focused on the management of a specific task, while others focused on the management of a transboundary biosphere reserve |

| Public/private nature of the resources | Mainly common-pool resources; public goods and socio-technical systems to a smaller extent | Diverse: private, common or public goods and services |

| Biodiversity values included | Economic values | Economic and non-economic values (e.g., fundamental and eudemonistic values [65], associated with the core and buffer zones) |

| Governance actors | Local communities | Diverse: governments, communities, non-governmental organizations, and/or multiple ways of collaboration between them |

| Roots | Institutional theory, collective action theory, rational choice theory and institutional change | The framework was developed to reflect the theoretical perspectives of the authors of the included studies (e.g., political ecology). The influence of the reviewer’s disciplinary background (ecology) cannot, of course, be discarded |

| Based in blueprint solutions? | No | Yes, to some extent (e.g., strict protected core area) |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferreira, A.F.; Zimmermann, H.; Santos, R.; Von Wehrden, H. A Social–Ecological Systems Framework as a Tool for Understanding the Effectiveness of Biosphere Reserve Management. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103608

Ferreira AF, Zimmermann H, Santos R, Von Wehrden H. A Social–Ecological Systems Framework as a Tool for Understanding the Effectiveness of Biosphere Reserve Management. Sustainability. 2018; 10(10):3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103608

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerreira, Ana F., Heike Zimmermann, Rui Santos, and Henrik Von Wehrden. 2018. "A Social–Ecological Systems Framework as a Tool for Understanding the Effectiveness of Biosphere Reserve Management" Sustainability 10, no. 10: 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103608