1. Web 2.0 Technologies for Collaboration in Distance Education

“Digital technologies are for education as iron and steel girders, reinforced concrete, plate glass, elevators, central heating and air conditioning were for architecture. Digital technologies set in abeyance significant, long-lasting limits on educational activity.” [

1]

“We need to explore what new and wonderful kinds of learning asynchronous environments make possible.” [

2]

Web 2.0 is a term introduced in 2004 by Tim O’Reilly, who described Web 2.0 as “the era when people have come to realize that it’s not the software that enables the web that matters so much as the services that are delivered over the web” [

3], and more recently suggested that “Web 2.0 is all about harnessing collective intelligence” [

4]. Despite widespread use of the term, an accepted definition of what Web 2.0 means is not easily found. According to Alexander and Levine,

microcontent (where authors create “chunks” of content each containing a primary idea or concept) and

social media (where the structure is organised around people, not directory trees) are two essential features that distinguish Web 2.0 projects and platforms from the rest of the web [

5]. In this paper, we take a broad definition, suggesting that Web 2.0 technologies are “second generation” world wide web technologies and applications, such as wikis and blogs, where internet users can edit, create and/or collaborate on web content easily using both synchronous and asynchronous tools.

Numerous papers have highlighted the contribution Web 2.0 tools, such as wikis and blogs, can make towards online social interaction [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] and collaborative learning [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Teachers and educators are realising that “wikis facilitate collaborative finding, shaping, and sharing of knowledge, as well as communication, all of which are essential properties in an educational context” [

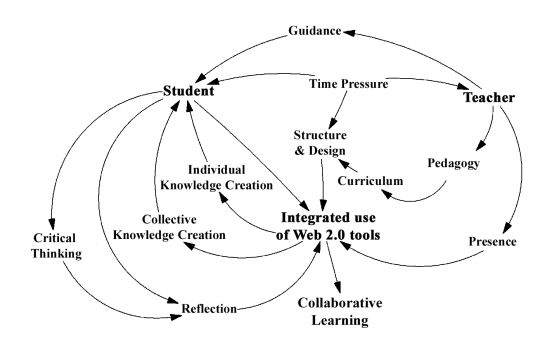

15]. In order to visualise some of the factors and interactions required for the successful integration of Web 2.0 tools for collaborative learning, we have developed a conceptual model (

Figure 1). The conceptual model is a visualization of the links between student, teacher and the use of Web 2.0 tools for collaborative learning. The conceptual model also illustrates possible negative influences on the system, for example time pressure or a lack of structure and design for the use of Web 2.0 tools in conjunction with the curriculum. The student is implicated heavily in terms of knowledge creation, both individual and collective knowledge creation. For this to be a reality, pedagogy and design of Web 2.0 tools as part of the curriculum must be given ample consideration, while further teacher guidance and presence is essential (

Figure 1).

Liu

et al. [

11] expect that “over the next two to three years we will see examples of Web 2.0 applications in all phases of teaching and learning [and that] further discussion should consider how to design Web 2.0 tools more effectively and how to integrate them into teaching and learning”. In this paper, the use of integrated Web 2.0 tools in higher education for problem-based collaborative learning is examined. Two case studies are presented, where asynchronous tools such as discussion boards, blogs, and wikis have been used, in conjunction with synchronous tools such as Elluminate Live! to develop collaborative approaches for distance education in an Australian university context. We have a particular focus on the use of wikis in the integrated context of Web 2.0 tools.

Web 2.0 tools, are used in the higher education context because they can: help engage students in their learning while providing social interaction with their peers in the learning process; enable students to work at the conceptual level of understanding on authentic projects where they can solve problems, discover relationships, discern patterns, and develop a deep understanding of content; and collaboratively build knowledge of students mediated by user-generated (either student or teacher) design; allow students and teachers opportunities for reflection; and, ultimately, cultivate communities of practice (

Table 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of a Web 2.0 community of inquiry, illustrating relationships between teacher, student and the integrated use of Web 2.0 tools.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of a Web 2.0 community of inquiry, illustrating relationships between teacher, student and the integrated use of Web 2.0 tools.

Table 1.

Opportunities for learning with Web 2.0 tools in higher education.

Table 1.

Opportunities for learning with Web 2.0 tools in higher education.

| Publication | Engage: Web 2.0 tools help students engage with learning | Social interaction: Web 2.0 tools support social interaction in the learning process | Conceptual understanding: Web 2.0 tools enable students to work at conceptual level of understanding | Critical thinking: Web 2.0 tools enable students to develop critical thinking | Construct collaborative knowledge: Web 2.0 tools enable students to collaboratively build knowledge | Construct individual knowledge: Web 2.0 tools enable students to build their own knowledge |

|---|

| [8] | | ● | | | | |

| [9] | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| [10] | | ● | ● | | | |

| [13] | | | | | ● | |

| [14] | | ● | | ● | | ● |

| [17] | | | | | ● | |

| [18] | | | | | ● | |

| [19] | | | | ● | ● | ● |

| [20] | | | ● | | ● | ● |

| [21] | ● | | | | | |

| [22] | | ● | | | ● | |

| [23] | | ● | | | ● | |

| [24] | ● | ● | ● | | ● | |

| [25] | ● | | | | ● | |

| [26] | | ● | | | ● | ● |

Learners develop socially when they collaborate with their more capable peers [

28]. Many authors see interaction as central to the educational experience and as a primary focus of online learning [

6,

28]. Web 2.0 technologies, such as wikis, facilitate communication via asynchronous interaction design options. In the online environment, participants can maintain engagement in a community, in the educational context a community of learners, when and where they choose [

28]. Van Aalst looked at an asynchronous Web 2.0 tool called ‘Knowledge forums’ for high school collaborative work, and discusses the importance of social dynamics, social infrastructure, social interactions for knowledge creation [

29]. From this study, Van Aalst identified, as one of the leading factors separating the group discourses, the social interactions needed to develop a sense of community [

29].

2. Weaknesses and Challenges in the Use of Web 2.0 for Collaborative Learning

Liu

et al. describe a lack of quantitative research on the effectiveness of Web 2.0 tools for teaching and learning, suggesting most papers measured teacher and student preferences for using Web 2.0 tools. They state that, “while some research studies reported that instructors and students liked using of blogs, wikis, and podcasting, the few comparison studies found no significant difference in learning outcomes when using these tools compared with an alternative instructional method” [

11]. Despite this lack of quantitative research on the effectiveness of Web 2.0 tools, a range of issues for students working with a wiki can be identified from the literature (

Table 2). These include issues around: content, for example students not feeling comfortable editing or deleting others work; process, including adequate time to participate, and student accountability for participation; guidance and protocols, the need for clear instructions, explanations, and rules for use; the need for teacher presence; issues associated with students who maybe unprepared for collaborative learning; and, finally, issues around wiki design and congruence with educational philosophy (pedagogy) (

Table 2).

Table 2.

Problems and challenges for the use of Web 2.0 tools by students in higher education.

Table 2.

Problems and challenges for the use of Web 2.0 tools by students in higher education.

| Publication | Content: Issues editing & deleting, commenting on peer work. | Process: Accountability of students for participation; Student role

versus the role of the tutor/lecturer. | Guidance: Inexperience, poor past experience & fear. | Teacher presence: Need for teacher/ instructor participation. | Solitary learners: Student unprepared for shared authoring & group work experience. | Design & pedagogy: Scaffolding; Pedagogic potential needs to match tool design, task authenticity. |

|---|

| [8] | ● | | | | | |

| [9] | ● | ● | | | | |

| [19] | ● | | ● | ● | ● | |

| [20] | | | | ● | | |

| [21] | | | ● | | | ● |

| [22] | | ● | | | ● | ● |

| [23] | | ● | ● | | | ● |

| [24] | ● | ● | ● | | | |

| [30] | | ● | ● | ● | | ● |

| [31] | | ● | ● | ● | | |

| [32] | | | | ● | | |

| [33] | | | | ● | | ● |

| [34] | | | | | | ● |

| [35] | | | | | | ● |

| [36] | ● | | | | | |

| [37] | ● | | | | | |

| [38] | | | | | | ● |

| [39] | | ● | | | ● | |

Cole reports on a failed attempt at using wikis to engage students in their own learning, and found the reasons for non-adoption by students included: academic pressure from other courses (educational constraints); ease of use concerns (technical constraints); issues of self-confidence (personal constraints); and a total lack of interest [

21]. Cole reflected that better design, suggesting scaffolding of the wiki in the course, may be needed to promote the use of wikis for collaborative learning in this instance [

21]. Wood

et al. provide an explanation of the use of scaffolding to support learning [

40].

There exists a large body of literature on the importance of teacher guidance and presence to the outcomes of online learning (for example, [

16,

28,

30,

33,

40,

41,

42,

43]). Reynard makes the point clearly that:

“… technology is only the tool and must be handled well by the teacher if the desired results are to be realized. Wikis are truly powerful tools to support collaboration; however, teachers are the central engager and the one who keeps the process moving forward. As students see their progress, they will continue to participate and even become energized as contributors in the process.” [

30]

The importance of teaching presence for adult learners in online learning environments is strongly argued by Ke [

32]. One conclusion Ke makes is that, “in spite of a common understanding that online learning gears towards a more independent and self-regulated learning, adult students have identified instructors who demonstrated high presence online as the key to learning satisfaction” [

32]. Douglas and Ruyters found that clarity in terms of explanations and requirements for the use of online tools, as well as teacher facilitation were required to ensure learning activities were successful [

42]. They suggest “developing student protocols to enhance communication online, allowing students the opportunity to “play” and rehearse and experiment with the tools, providing an exemplar and teacher modeling to scaffold learning and finally ensuring that there is a teacher presence in the online environment to validate and encourage student interactions” [

42]. This finding is supported by Augar

et al. [

43], who describe a wiki used as an ice-breaker for students to familiarize themselves with Web 2.0 tools.

Issues of interaction, both social and cognitive have also been found factors for students adjusting to online learning [

33]. Garrison and Cleveland-Innes suggest that because of this, students are not always prepared to engage in critical discourse, especially if this is in an online learning environment [

33]. For some authors, “the extent to which instructors will choose to engage students in collaborative learning remains a moral issue … one grounded in each instructor’s own beliefs about teaching” [

34]. It might seem obvious, but it is necessary to state, that if collaboration and/or collaborative knowledge creation is not a clear goal, then Web 2.0 tools are probably not the best technology to adopt in any situation, including education. In fact the use of wikis outside of the collaborative context may prove problematic [

22,

35]. The educational philosophy underpinning the curriculum plays an important role in the choice of which Web 2.0 tools to use for distance education.

In addition to design, structure and leadership are critical elements to be considered to allow online learners to “take a deep and meaningful approach to learning” [

28]. Thompson and Absalom reported that “the inherently collaborative nature of social web technologies cannot be separated from the complex, ever-evolving and potentially disruptive process of identity formation, which co-occurred as students engaged in the co-creation of Web 2.0 enabled texts and artefacts” [

18]. Elgort

et al. considered students’ and lecturers’ views on using wikis in the context of course group work, and found that “the use of wikis was not enough to counteract some students’ preference for working alone rather than as part of a team” [

22]. They found that distance students may choose to use wikis in order to feel less isolated, and on-campus students also felt that it was a good way to get to know other members of the class [

22]. According to them, distance students also looked for other ways of compensating for the lack of face to face contact, such as self-initiated audio conferencing sessions [

22].

The remainder of this paper examines two cases where Web 2.0 technology has been used for distance education in an Australian higher education. In both courses wikis, blogs and other Web 2.0 technologies were used to facilitate collaborative learning. Online collaboration was required in order to fulfill pedagogical objectives for authentic, problem-based learning, and the development of critical thinking skills. A brief overview of each course is presented, followed by a discussion about what these courses tell us about the use of wikis in the context of distance education from the students and teacher perspective, and in light of the literature presented earlier.

3. Two Case Studies Using Web 2.0 Technologies for Distance Education

As late as 2008, Bonk and Zhang were curious to “see how instructors and institutions take advantage of (Web 2.0) interactivity … (and) to watch learner reactions” [

44]. This section describes two cases in an Australian University where Web 2.0 tools were used to facilitate collaborative learning. The Web 2.0 tools included asynchronous tools such as blogs, discussion boards, and wikis, integrated with synchronous tools such as Elluminate Live!. Three of the authors were directly involved in the design, and delivery of the units described in the two case studies. Rowe was the Unit (subject) Assessor for Case 1, Advanced Financial Accounting, Lloyd was the Unit Assessor for Case 2 PCRM, and den Exter was the Associate Lecturer in Case 2.

The evaluation of Web 2.0 tools for collaborative learning that follows is an ex-poste evaluation, and these cases are contrasting examples of early adoption in the use of integrated Web 2.0 approaches for collaborative learning at Southern Cross University. For these reasons, we have taken a predominantly qualitative approach to evaluation. Where possible, quantitative data provided by the Blackboard learning management system is also used. All relevant student comments have been drawn upon and summarized in relation to the use of Web 2.0 tools for each case. The comments made by students were made as part of their own individual (private) reflection blogs, which, although were assessment requirements of the unit (subject), were not graded in terms of the content. Students were encouraged to voice their experience, their opinions, what they liked and what they did not like about the use of Web 2.0 tools.

3.1. Case Study 1, Advanced Financial Accounting

Case 1, Advanced Financial Accounting (AFA), is an optional unit available in the Advanced Accounting major of the Bachelor of Business offered by the Southern Cross University Business School. Enrolments are typically small, facilitating a close working relationship with individual students who are nearing the end of their degree. 15 students enrolled in 2008. There were 5 withdrawals and 10 grades were awarded for successful completion of the unit.

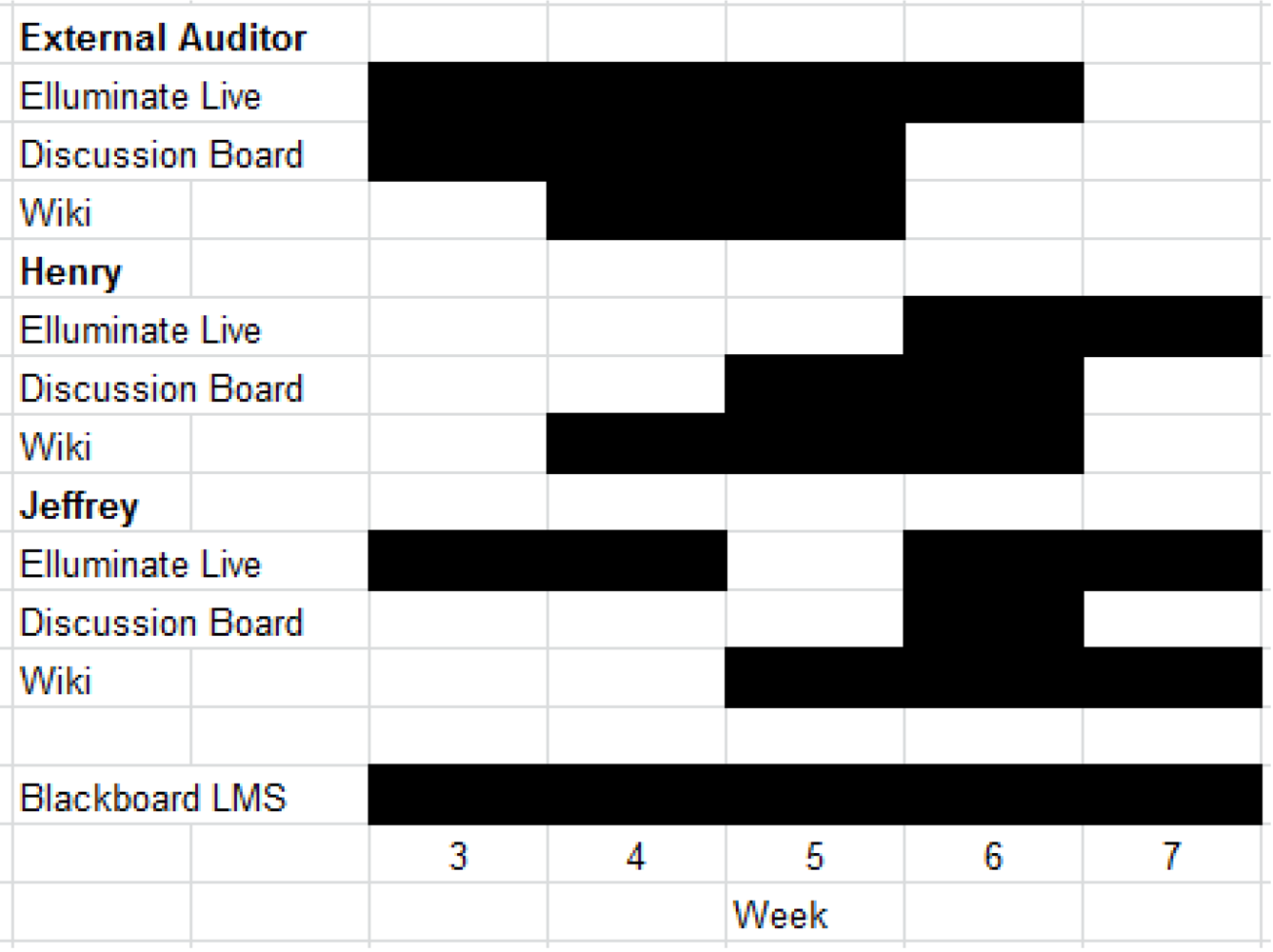

AFA has been offered entirely online since 2003, and utilises an ever-evolving range of asynchronous (discussion forum, blog, wiki) and synchronous (Elluminate Live!) Web 2.0 technologies accessed using the University Learning Management System (LMS) (

Figure 2). Apart from some background readings and case study material, the LMS site at the beginning of the teaching session is, by design, a blank slate. Content is developed and created as a direct result of student engagement in their learning. There are non-compulsory weekly live online meetings scheduled for 2 h (7.30–9.30 pm). These meetings were recorded and available for attendees to review, or non-attendees to view. There were seven assessment tasks to be attempted for the unit. There is no final examination. The nature of the advanced units is expressed thus in their Unit Information Guide:

“Rather than learning about how to process numbers, you focus on problems, alternatives, and deciding what numbers to use. … You will have the opportunity to work alone, to work with colleagues … The idea is to collaboratively learn, but individually utilise and present what you are learning.”

Figure 2.

Timeline for Case 1 (AFA), showing the use of Web 2.0 tools over the teaching session. External Auditor, Henry and Jeffrey are names for the three student groups engaged in this learning activity.

Figure 2.

Timeline for Case 1 (AFA), showing the use of Web 2.0 tools over the teaching session. External Auditor, Henry and Jeffrey are names for the three student groups engaged in this learning activity.

Four assessment tasks had prescribed due dates, and three required students to make choices about when they completed the task. The latter were to offer flexibility for students, to cater for the myriad of constraints they need to deal with in their workloads. Four tasks were worth 10% each, the remaining three worth 15%, 20% and 25% respectively. One of the assessment tasks required students to maintain a personal Learning Reflection Blog (LRB, 10%). This was the only assessment task that was private between the student and the unit assessor; all others were public for all enrolled students in the unit to see. The online class and the reflective blog provided direct synchronous and asynchronous lines of support from the unit assessor (one public and one private).

The introductory task (10%) was due in Week 2, and was designed to have students use a blog, a wiki and a discussion forum. By the end of Week 2, the Introductory Activities had been completed by 11 of the 15 enrolled students, and 8 had attended a live online meeting. This meant that those students who had completed the introductory task and attended weekly online meetings had been exposed to all the technologies they were required to use for the unit by the end of Week 2. The following is a typical initial LRB contribution at the beginning of the session:

“After reading the Unit statement and the Unit Introduction, I felt a little uneasy about the subject as it noticeably differs from all the other units I have studied so far at uni, particularly as nothing of the unit content seems to have been set down at the start. But after working through the introductory activities I do feel more comfortable, particularly as I now understand how the unit will form as the semester progresses. It is also good that the unit seems to further encourage collaboration and simulates a small classroom sort of situation, where everyone is encouraged to interact, as opposed to other external units which feel more isolated.”

There were two case studies among the assessment tasks. Both case studies are designed to demonstrate the challenges of exercising professional judgment in the application of accounting standards for financial reporting purposes when there is conflicting and incomplete information available. The first case study (15%) is due by Week 4, and requires individual contributions to a case wiki about specific financial reporting decisions. The weekly contributions are discussed in the live online meetings to make the variation in interpretations transparent and the basis for development of individual arguments on the wiki. Final individual decisions are submitted using a word template during Week 4, collated ready for comparison during the live online session. Students have the option to resubmit their template based on meeting discussion, reflection and individual formative feedback offered. This case highlights one possible design of a task using wikis to construct collaborative knowledge (individual sharing of interpretations and professional justifications) to enable the construction of individual knowledge (the template showing final individual judgments). The design also highlights the integration of parallel asynchronous technologies (the LRB) and the synchronous technology (live online sessions) into the learning process.

The remainder of this report focuses on the second case study (20%), which involves a group component and a final individual decision. The ambiguity introduced by the collaborative nature of the discussion informing individual submissions from the first case study is now transferred into a group task. The case study (Grey Paints) requires students to self-select into one of three groups–External Auditor (“Auditor” from here on), Henry, Jeffrey (

Figure 2). Each group takes one of three perspectives for evaluating the operations of a company in the first year of a succession plan being implemented, that saw a son (Jeffrey) take over running the business from his father (Henry). The third independent perspective is the external auditor, tasked with reviewing the results of the first year under Jeffrey’s stewardship. Alternative accounting interpretations can be justified from each perspective. After hearing and discussing each perspective, individuals had to decide whether they believed Jeffrey had performed better by the end of the first year than Henry had when he handed over the running a year earlier.

Students self-select into a group on a first-in, first-served basis using the discussion board and takes place by Week 3 (11 March). Four enrolled students had withdrawn prior to the due date and one withdrew after nomination but prior to groups being settled. This meant that at the time nominations closed each group had the following members: Auditor (5), Henry (4) and Jeffrey (1). One of the students in the Auditor group agreed, during our first class discussion (11 March), after nominations closed, to move to the Jeffrey group to even numbers up, and another student ended up moving from the Auditor group to Jeffrey due to extenuating circumstances later in the process (25 March). One student in the Henry group did not participate at all (though did complete the other assessment tasks). This meant the final effective number of participants in each group was Auditor (3), Henry (3) and Jeffrey (3).

Table 3 shows the variation in extent to which each of the technologies were accessed and used for each group up until the due date for the task. What is clear is the variation in extent to which groups engaged with each technology across the allocated time for the assignment.

Table 3.

2008 Grey Paints Case Group Activity Summary.

Table 3.

2008 Grey Paints Case Group Activity Summary.

| Tool & Activity Use(up to due date) | Group |

|---|

| Auditor | Henry | Jeffrey |

|---|

| Discussion Forum posts | | | |

| Nominations | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| Organisation/general | 17 | 5 | 4 |

| Total | 22 | 10 | 5 |

| Elluminate attendance | | | |

| Class breakouts | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Self-organised | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Group presentation | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 6 | 4 | 7 |

| Group Wiki contributions | | | |

| Number of pages created | 22 | 11 | 8 |

| Number of page saves | 303 | 160 | 33 |

| Number of lines modified | 1991 | 6530 | 1102 |

| Number of days accessed | 9 | 11 | 9 |

| Individual Blog contributions | | | |

| Progress posts | 35 | 14 | 11 |

| Final decision/reflection post | 3 | 3 | 3 |

An examination of dates for contributions made by technologies indicates that the Auditor group engaged earliest. They were also very active during the semester study break. The Auditor group was scheduled to present a week earlier (1 April) than the Henry and Jeffrey groups (8 April). The Henry and Jeffrey groups did not substantially engage outside of online meeting discussions until after the Auditor group had presented their perspective.

Based on the group activity and group presentations, each individual had one week to post their final decision about whether they believed Henry or Jeffrey had performed “better”. This was their individual decision based on the persuasiveness of each group perspective and the independent input from the external auditor. One student decided neither deserved to win; two chose Jeffrey, with the remaining six choosing Henry. Those in the Henry group remained loyal (all three); only one remained loyal in the Jeffrey group, with the other two being persuaded to the Henry perspective; and the independent auditor group were split one for Jeffrey, one for Henry and one for neither.

The final marks awarded reflect the group element and the individual element. Group mark out of 15 varied as follows: 13 (Auditor), 13 (Henry), 12 (Jeffrey). Individual marks out of 5 for Auditor (3 × 5 each); Henry (1 × 5, 1 × 4, 1 × 2) and Jeffrey (2 × 5, 1 × 1). The one student who did not participate in the Henry group received 0 for both components.

3.2. Case Study 2, Principles of Coastal Resource Management

Case 2, Principles of Coastal Resource Management (PCRM), is a 2

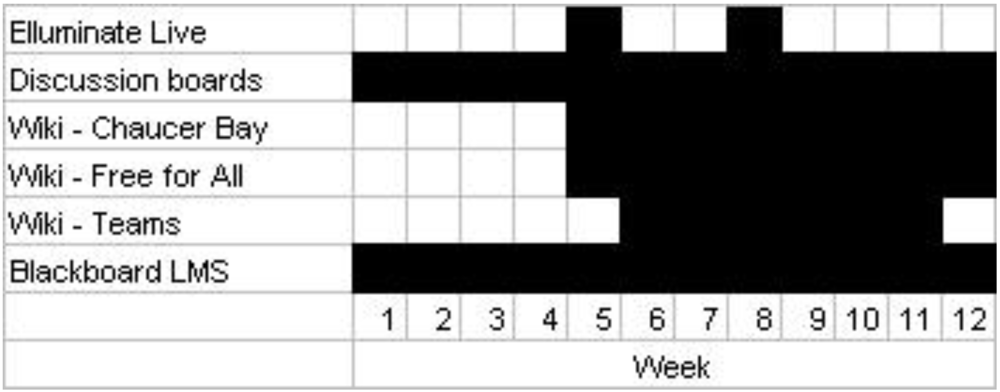

nd year undergraduate unit of 73 students, taught for the first time in 2011 as a session-long online unit (

Figure 3). All students were treated as distance education students, even if normally enrolled on-campus. The course utilises a range of Web 2.0 tools, including the use of computer-based scenarios, wikis and blogs (

Figure 3). In PCRM wikis were used to: provide support to the problem/project based learning scenario (the Chaucer Bay Council and Free-for-all wiki); and encourage collaboration on the final assessment task–environmental impact assessment (team wikis). These tools were employed to provide authentic, problem/project based teaching/learning experiences for developing higher order thinking and problem solving skills. In Week 5 of the semester students assume the role of Coasts & Estuaries Officer (for the fictional Chaucer Bay Council). The two lecturers (Lloyd and den Exter) became Council Managers.

Figure 3.

Timeline for Case 2 (PCRM) showing the use of Web 2.0 tools over the teaching session.

Figure 3.

Timeline for Case 2 (PCRM) showing the use of Web 2.0 tools over the teaching session.

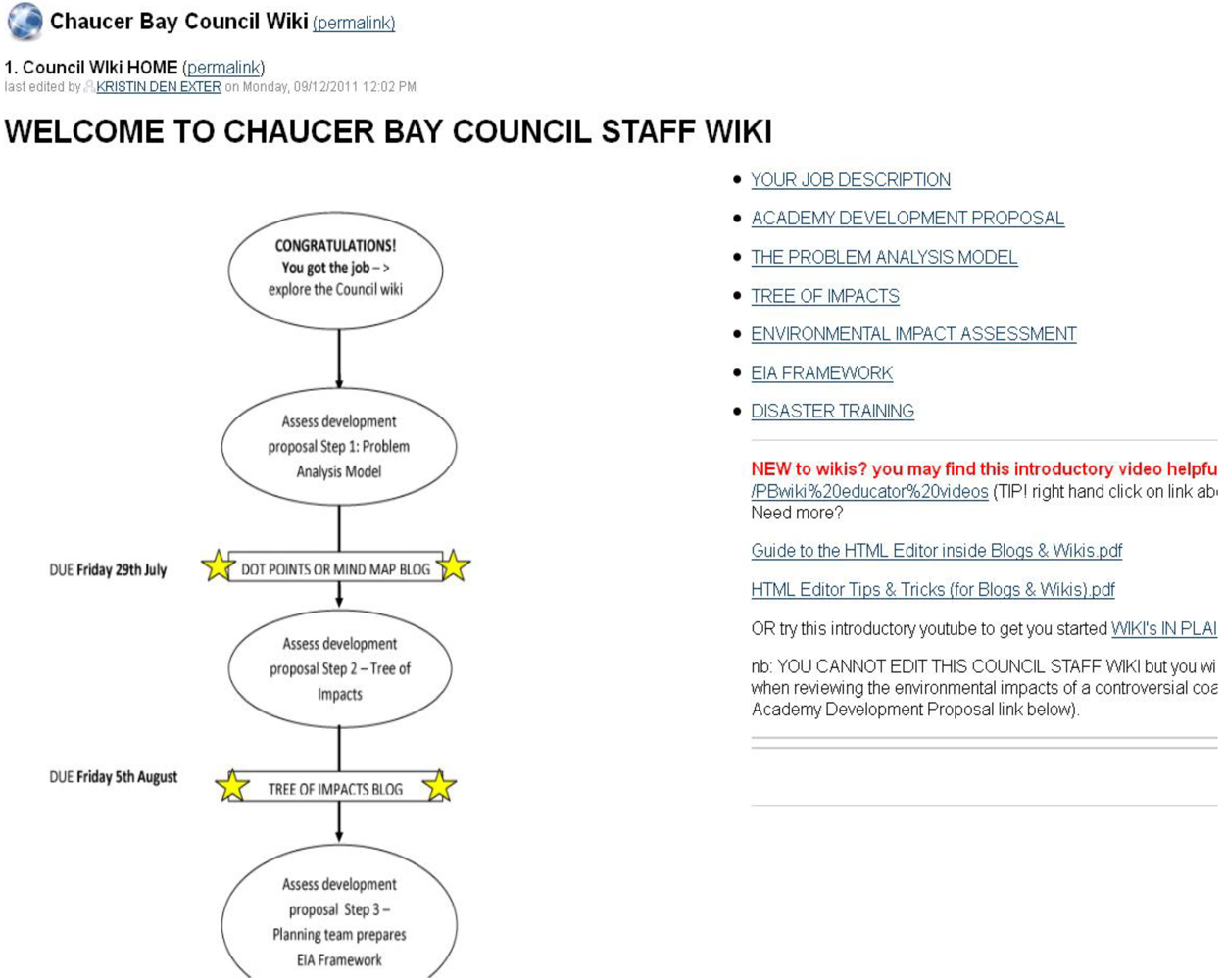

A highly structured, un-editable wiki, the “Chaucer Bay Council Wiki” (

Figure 4), guided students through the scenario-based learning problem from Week 5 to Week 12 (

Figure 4). The idea was to immerse the students in their new role, and help them understand the what, why and how of a wiki, using instructions and links to other resources for new wiki users. These guides and resources were also provided in the class free-for-all wiki, where students were encouraged to create a page, introduce themselves, and upload photos.

Students were expected to use the two guide wikis and then, in groups of 3–4 assigned by staff, create their own group wiki collaboratively, based on a brief, without being prescribed any structure or content. This was a major assessment exercise for students worth 40% of their marks. Blogs were used throughout the unit to promote self-reflection and reflective thought processes; each blog was worth 5%. One blog exercise asked students to reflect on their experience working with their team collaborating on wikis. Two synchronous Elluminate Live! meetings were conducted over the learning scenario for staff to trouble-shoot any issues students were having.

Site statistics show usage of some of the Web 2.0 tools by students. The “Chaucer Bay Council Wiki” was accessed a total of 1183 times by students between 20th June 2011 and 20th September 2011 (average 16 hits per student). Fifteen students did not access the Chaucer Bay Council Wiki at all, and these students either withdrew or did not successfully complete the unit. One student accessed the Chaucer Bay Council Wiki a total of 78 times (this same student also received the highest mark for the subject).

Figure 4.

The Home page of the ‘Chaucer Bay Council Wiki’ wiki used in PCRM to situate students in their scenario-based learning approach, and provide introductory resources on how to use wiki’s. Students created their own wikis, according to their own design, for their major group work.

Figure 4.

The Home page of the ‘Chaucer Bay Council Wiki’ wiki used in PCRM to situate students in their scenario-based learning approach, and provide introductory resources on how to use wiki’s. Students created their own wikis, according to their own design, for their major group work.

Team wikis, those wikis created by the student groups with an assignment brief, but without a pre-defined structure, were accessed a total of 5205 times by students (average 70 hits per student) over the Session, with one student (the top performing student mentioned before) accessing their team wiki 503 times (only slightly fewer times than the Associate Lecturer (tutor) who accessed this content area a total of 535 times over the same period). How students used the free-for-all and team wikis as well as group pages incorporating file exchange and discussion boards is summarised in

Table 4. The usage and hit rates suggest active engagement from students with the wiki environment.

Thirteen of the fifteen groups submitted their collaborative work using wiki structure. Three groups uploaded a file for download into the wiki. One group chose to present their collaborative output both as a wiki, and as an embedded file for download. Of the thirteen teams to submit using wiki structure, five used hyperlinking, five used embedded graphics, and four teams included embedded tables. Despite a list of fourteen potential non-engagers (based on LMS site activity in the lead up to Week 5) only five groups experienced problems around participation, with six students designated as non-participators. Staff allocated each group one potential non-engager, despite this one group experienced two drop-outs. The average grade for the group work was 75.5% and team grades ranged between 65% and 96.3% (

Table 4). The teacher in charge of marking this assignment reflected that the quality of the group work exceeded previous years’ individual efforts.

Table 4.

The use of Web 2.0 tools in PCRM by students. The “Free-4-all” row shows usage of the “Free-for-all” wiki; wiki students equals the number of students contributing to each wiki per team. Db students showing the number of students contributing to the discussion boards per team. File exchange shows the number of documents posted by each team to the learning management systems file exchange. Db shows the number of posts made by students in each teams group discussion board. One teacher was present in all wikis.

Table 4.

The use of Web 2.0 tools in PCRM by students. The “Free-4-all” row shows usage of the “Free-for-all” wiki; wiki students equals the number of students contributing to each wiki per team. Db students showing the number of students contributing to the discussion boards per team. File exchange shows the number of documents posted by each team to the learning management systems file exchange. Db shows the number of posts made by students in each teams group discussion board. One teacher was present in all wikis.

| Wiki | Pages | View | Edit | Deleted | Student | Teacher | File exchange | Db posts | Db students | Grade % |

|---|

| Free-4-all | 16 | 988 | 49 | na | 15 | 1 | na | na | na | na |

| Team 1 | 12 | 2775 | 431 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 27 | 4 | 96.3 |

| Team 2 | 4 | 137 | 21 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 27 | 4 | 76.3 |

| Team 3 | 1 | 68 | 37 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 53 | 3 | 75.1 |

| Team 4 | 1 | 62 | 12 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 65.0 |

| Team 5 | 5 | 151 | 28 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 4 | 65.0 |

| Team 6 | 4 | 441 | 75 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 40 | 4 | 65.0 |

| Team 7 | 46 | 1438 | 328 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 22 | 108 | 4 | 90.0 |

| Team 8 | 6 | 299 | 67 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 32 | 4 | 67.5 |

| Team 9 | 7 | 197 | 22 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 70.0 |

| Team 10 | 2 | 86 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 35 | 4 | 96.3 |

| Team 11 | 12 | 899 | 179 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 14 | 4 | 67.5 |

| Team 12 | 4 | 216 | 26 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 32 | 2 | 70.0 |

| Team 13 | 5 | 615 | 55 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 26 | 4 | 72.5 |

| Team 14 | 4 | 602 | 82 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 23 | 4 | 86.3 |

| Team 15 | 3 | 41 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 68.8 |

| TOTAL | 132 | 9015 | 1421 | 17 | 64 | 1 | 56 | 447 | 54 | |

Communication between group members in PCRM was a common theme in the students’ reflection blogs and clearly some groups were more successful at communicating than others:

“A couple of issues presented themselves during the process, mainly stemming around the lack of real conversation, and human contact. Working in this type of situation is difficult when trying to manage timeframes. When working as a group face to face, you are able to throw ideas around straight away, but the problem we had was that it took a few days before you found out the opinions of others.”

“This project has been a challenge with some of us being in different areas and timezones. There has been the same effort applied by all in the group at different times, due to this, and overall this has been a success. Personally I have found this project to be similar to the ones I have been involved in within my professional life in remote areas where there is little personal interaction and the life of the project being decided by emails and other electronic communications that I have never personally met.”

Students in PCRM commented on authenticity and the social interaction as a positive experience:

“As this is potentially a task I would be doing in my employment after university, I found it of great value. Overall this assessment task has been very useful, not only academically but also to get to know some other students within the environmental sector.”

And from another student:

“The EIA group assessment was a very interesting assignment as we were placed in a real working scenario. I liked the aspect that we had a deadline to meet and that we all had to work with each other to produce a thorough, informative Environmental Impact Assessment.”

Student reflections in PCRM show that many found that using a wiki based scenario was a “great concept”, allowing for important collaborative learning that they do not often experience. Some internal students did not like the online group work, noting the different work habits of internals versus external students, and feeling that the online group nature of the assessment was too challenging. Project management (workflow), timing, time pressures and student roles and groups dynamics provided challenges with some groups better than others at organising themselves: “It is frustrating that even with every attempt I made to organise things so we could assist each other and have it up in ample time for editing that this was not achieved by everyone”. Content management was also a concern with some students unable to edit or delete others work: “At one stage I found myself a little hesitant to change too much of someone else’s work or add something that maybe wasn’t right however I was fine with editing or having people change/add to my page”. However, other students enjoyed the collaboration (“on the wiki which was constantly updated and edited by the group”) while others reported finding the editing options easy and pleasing:

“I found editing and adding to the Wikis very easy and pleasing. I liked how the tools were literally at your fingertips and any time that you found the motivation or inspiration to add to the wiki.”

4. Discussion

“The purpose of an educational experience, whether it is online, face-to-face, or a blending of both, is to structure the educational experience to achieve defined learning outcomes. In this context, interaction must be more structured and systematic. A qualitative dimension is introduced where interaction is seen as communication with the intent to influence thinking in a critical and reflective manner. Some have argued that in higher education, it is valuable and even necessary to create a community of inquiry where interaction and reflection are sustained; where ideas can be explored and critiqued; and where the process of critical inquiry can be scaffolded and modelled. Interaction in such an environment goes beyond social interaction and the simple exchange of information. A community of inquiry must include various combinations of interaction among content, teachers, and students.” [

28]

Web 2.0 technology has been widely adopted for education, and in many instances been successfully used. However, students are still finding this approach unfamiliar, as demonstrated in both the AFA and PCRM cases. As one student in a discussion board says: “I have not used Wiki before … how do I do it?”. Another jokingly responds, “You are not alone, I have never encountered a Wiki. (Is that a bit like a Wookie but with a higher pitched voice?)”. It seems wikis are still new to many university students, even in a second year subject in 2011. In PCRM, students initially found the technology challenging, but gained confidence with experience:

“Being a wiki first time user, the EIA assignment presented itself with many challenges. Looking back on the exercise there are certainly many ways our group, including myself, could have implemented the use of the wiki devise more effectively … Once over the initial scare of how to operate the wiki and frustration with tables and inserting pictures to display the wiki as wanted. There was the realisation that the wiki is an easy to navigate, successful communication instrument that can be implemented in various settings.”

Despite this unfamiliarity with Web 2.0 tools, both cases described here show that asynchronous tools such as wikis, blogs, file exchanges, discussion boards, and synchronous communication tools (e.g., Elluminate Live!) can be successfully integrated for collaborative learning amongst distance education students in both small and large groups. The role of Web 2.0 tools for knowledge creation, critical thinking and reflection has been discussed elsewhere (e.g., [

14,

20,

45,

46,

47,

48]); Wenger

et al. [

49] discuss technology and its role of in support of communities of practice. We focus in the remainder of this paper on what we have learnt from our case studies in terms of the student-teacher roles, and examine whether it is better to take a structured versus an emergent approach to design. Jackson

et al. argue that “it is important not to rely entirely on emergent design forms, but to provide strong guidance in site structure, layout and information design to students and knowledge workers” [

23]. Meishar-Tal and Gorsky state that “teachers and instructional designers determine the nature of collaboration; that is, the division of labour, role-taking and the activities to be carried out” [

19]. We ask to what extent should they? Does it depend on the nature of the exercise and the reason for using the Web 2.0 technology in the first place?

The “uneditable and highly structured” design of the demonstration wiki for the PCRM case contrasts markedly with the more emergent design and use of the wiki for the AFR case. However, the student wikis themselves (the assessment task) in PCRM represent more of an emergent approach. The assessment task for PCRM was more stand-alone and less integrated with other assessment tasks than in AFR. The PCRM task was worth 45% (including the final blog reflection), whereas the AFR task was worth 20% (including the final blog reflection). The end products were also quite different, although neither were tightly prescribed. For PCRM, students had to produce a written report constructed using the functionality of the wiki. For AFR they needed to debate, organise and prepare for a 30 minute group presentation during a regular weekly online meeting, and use the collaboratively constructed knowledge as the basis for their final individual decision, contributed privately on their LRB.

Another point of variation in design was the approach to initial support and guidance for students about how to use wikis. This was set up in two ways in PCRM in Week 5 at the outset of the scenario-based learning exercise, by the provision of the Chaucer Bay Council wiki, which was used throughout the learning scenario to give student structure and guidance, and a discrete free for all or sandpit wiki for students to experiment with around an exemplar page: “At first I found this exercise difficult and frustrating as I had trouble using the Chaucer Bay wiki, however after running through the web pages a few times it became more clearer”.

In AFR, students started using wikis in Week 1, and continued to do so across the semester, with the content being developed and drawn on for weekly online class meetings. The use was thus much more dynamic and integrated into unit activity and tasks. The success of this early engagement in AFR is captured in this Learning Reflection Blog (LRB) contribution during Week 1:

“The introductory activities gave me an insight as to what the unit would entail. It made us communicate and socialise in a sense with the other students enrolled in the unit. This made the unit seem and feel more personalised as being ‘online’ made it seem it would be an impersonal experience. However, this was not the case and it was interesting to see what background everyone in the course had. They also had us using the internet to research early on and of course getting to know what a wiki was and how to use one.”

The different ways that the activity of each group in each unit is reported also speaks to design issues. In PCRM, the site statistics feature of the Learning Management System (LMS) was used to show activity within and across wiki groups. This shows access to various areas of LMS where wiki activity occurred, but little about the development of the content itself. In contrast, the AFR activity is reported from the Assessing Wiki feature of the LMS, and shows proportional indicators of content development (lines and pages created, modified and saved as well as the number of days wiki activity took place). Ideally, both sources would have been captured for both units; this is a lesson we take from the analysis presented here.

What the collection of activity statistics from both units highlighted was the need to recognise that group activity involves more than just the wiki if it is to be evaluated in a meaningful way. The numbers alone tell such a small part of the process and outcome of the tasks. For PCRM contributions using the File Exchange and discussion board features provided a clearer picture of individual involvement in the group activity. In the more emergent AFR case, discussion forum posts were most prevalent during initial and preparatory stages. The use of breakout rooms in weekly online meetings and self-organised online meetings provided further practice and familiarisation with technologies also used for their group presentation. The supplementary value of regular blog contributions has already been mentioned. Both cases, more or less structured, point to the importance of recognising the range of activity and interaction that occurs off-wiki. The wiki really is the repository of evidence for what was organised and created elsewhere in a variety of ways.

One other important difference is the integrated role of the weekly online meetings in AFR as another opportunity for reflection and debate of alternative perspectives across the period of the case. This was important in two ways. First, it provided a synchronous supplement between (student) groups rather than just allowing within-group discussion. Second, it was a synchronous supplement to the asynchronous dialogue with the unit assessor on the private LRB. A key part of learning is to facilitate and foster time for student reflection and permission to explore and acknowledge differences that may or may not be resolvable. This range of channels for ongoing dialogue provided the permission and safety to discover alternative perspectives and explore potential resolutions. This following two extracts from final LRB contributions by AFR students sum up the value of the integration for student learning:

“At the beginning of the semester I was a bit apprehensive towards the online structure of this unit, having had 4 years of textbooks and study guides it was more a case of familiarity and a fear of the unknown. The format of assignments was also a new concept to me and one that I was unsure of at first, particularly with choosing our own topics for the presentation and working with other students for the Greys case. However, I now appreciate that this format allowed us to think for ourselves and, as in life, there is not always a lot of structure and guidance but it will usually be provided if asked!”

“The weekly Elluminate sessions were a great way to interact with the other students, especially in regard to the group assessment tasks. In the beginning they were a bit slow because no one was very talkative (including me). Throughout the semester I became more comfortable and confident using the microphone and becoming more involved in each session.”

In PCRM, student groups were expected to work in a more independent, self-regulatory way in their team wikis. Elluminate Live! meetings were held twice over the six week scenario-based exercise to offer the students troubleshooting support. Another distinction can be made around the use of blogs. PCRM used a number of discrete blog tasks for reflection and assessment, whilst in AFR the LRB was open all semester for students to reflect on anything to do with their learning along the journey. The AFR blog was thus much more open-ended and, because it was private, offered a direct asynchronous connection with the unit assessor across the semester. During the period of the AFR case 39% (60) of the total number (154) of LRB posts were added. Just over half of these were from the Auditor group members, with the remainder evenly split between Henry and Jeffrey group members. This seems to demonstrate an important supplementary channel of communication for group members to clarify and resolve progress in their own minds.

The following LRB contribution offers a valuable insight into how a student can benefit from the unstructured emergent nature of the AFR case(s). This student was one of the quieter students (measured by activity), but the contribution indicates a good deal was happening in the observation of and (seemingly limited) involvement in the case activity—perhaps what some online literature would term a lurker or solitary learner:

“But as I progressed in the unit especial with Greys Group and the resubmission of Duncan case, I realised that we actually do have all the materials needed, we were just not guided there, we had to look for it ourselves. I like that we are not learning specific topics that relate to specific standards, I also very much enjoyed the group work and learnt heaps from it especially how to apply the standards and that just stating this relates or complies with this particular standard is not enough, you have to actually say and understand why, because you might be challenged on it, as the case with the presentation of Jeffery and Henry’s group.”

In PCRM, while some students found the use of a fictional setting (Chaucer Bay) confusing [

50], and others would have liked more of a defined structure for the assignment, student reflection suggests that the scenario, and the unstructured nature of the team wiki project gave the assessments authenticity and taught the students about group process, and team dynamics as much as did about the topic of environmental assessment:

“I also initially had difficulty understanding what the assignment actually asked and questioned how I was going to communicate with 3 people I had never met before? … Overall I felt the assignment was a healthy challenge and that I gained some valuable skills which I can use in future similar scenarios. The assignment helped me the think outside of the box in ways of determining answers, I feel that I now look at a question in numerous ways. It showed me how different everyone thinks and sets out an assignment or just a simple task.”

5. Conclusions

Our case studies illustrate the flexibility of designing an integrated Web 2.0 community of inquiry can lead to significant learning opportunities for distance education students, not just in terms of content but also because of the interaction between teachers and students and students themselves. How the system is designed depends on many factors including the time available for both teacher and student, the pedagogical goals and curriculum. The flexibility, and relative ease of use, of many Web 2.0 tools, especially when used in an integrated way presents almost unlimited opportunities to facilitate collaboration with distance education students.

Our case studies confirm the potential for the use of Web 2.0 for distance education, the important role of teacher guidance, clear instruction and the need to match the design of Web 2.0 learning systems with pedagogical goals and the student-teacher context. Whether this means the design approach is more structured or more emergent also relates to pedagogical goals, but also may depend on the size of the class, and the time available for teachers. For an emergent approach to be successful, as demonstrated by the AFA case study, the teacher needs to be present throughout, facilitating the journey, and Web 2.0 tools tightly integrated, offering students flexibility and an opportunity to contribute when and where appropriate over time. Initial activities provided the guidance needed, and increased student confidence around the use of Web 2.0 tools. The PCRM case study shows that initially using a tight structure, and model wikis, can also provide the guidance needed for students to successfully move into a more emergent approach. Our findings suggest that it may be more useful to view structure and emergence as a gradient, than as a choice that must be made.

Interaction is critical to the Web 2.0 community of inquiry, interaction between teachers and students, the students themselves, and for both teachers and students with the Web 2.0 environment. The design of the Web 2.0 environment clearly has a key role to play outcome of the interaction. The two case studies described here, like much of the current literature available, present the voice of early adopters and the report on the experience using the voice of students. This qualitative benchmarking is useful in its own right. However, empirically testing hypotheses around social interactions and learning outcomes, using carefully designed tests with control groups, would be a fruitful area for further research. Further investigation into the best use of the LMS reporting systems, in order to compare the outcomes of different curriculum and tool designs, is also needed to learn as much as possible from our applied use of virtual Web 2.0 environments and the social interactions that take place within them. A final note from a PCRM student on the use of wikis suggests that their use will perhaps become the norm for collaboration over distance:

“The wiki was excellent and a great way to work together as a team without the luxury of face to face contact … I cannot imagine attempting group work in any other way now that we have this technology available to us.”