Investigation of Electric Field–Induced Structural Changes at Fe-Doped SrTiO3 Anode Interfaces by Second Harmonic Generation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

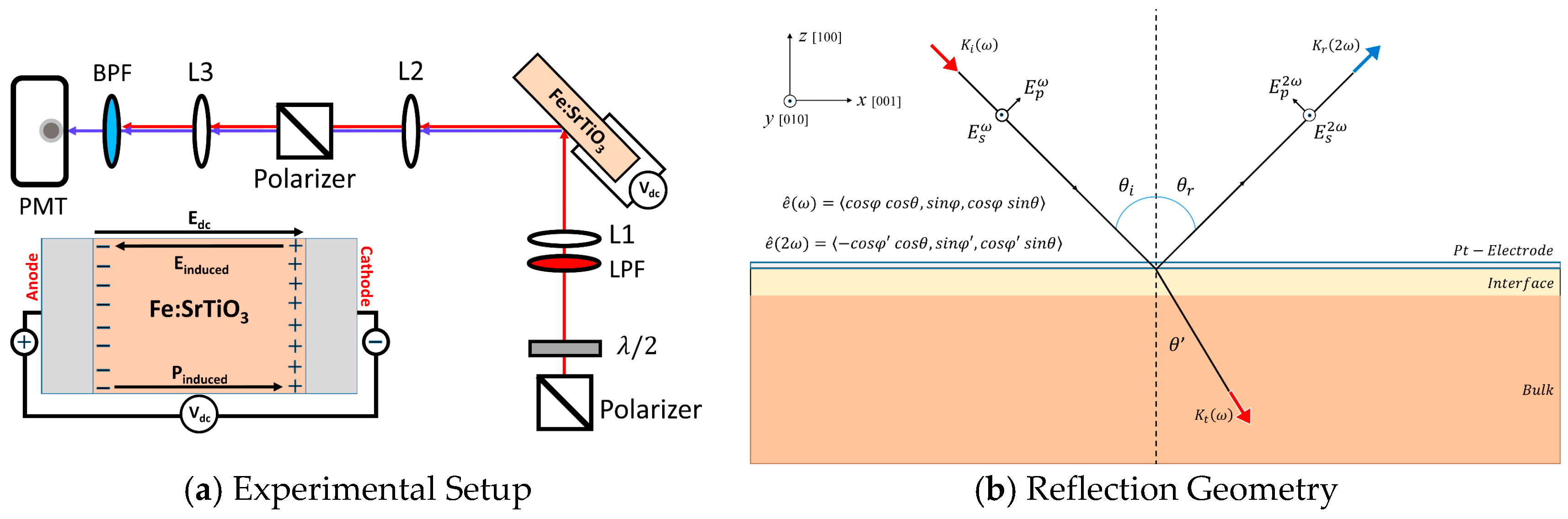

2. Experiment and Theory

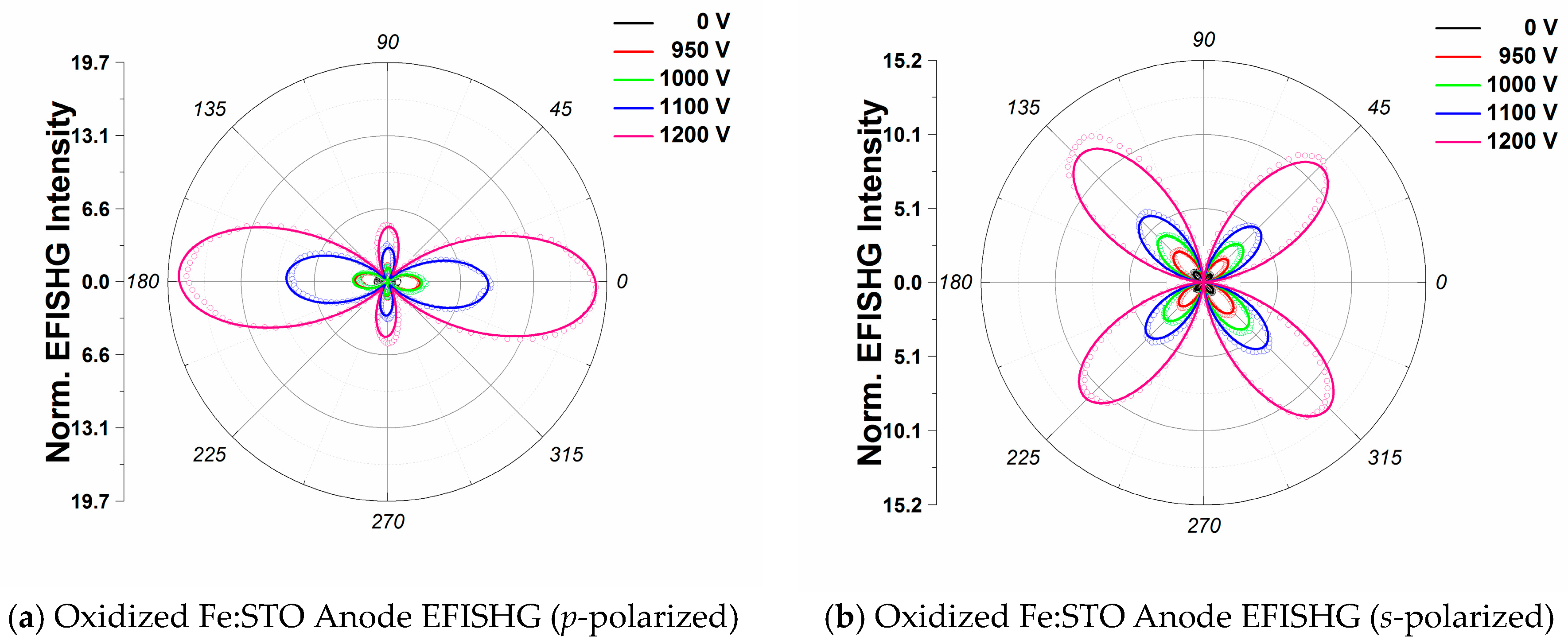

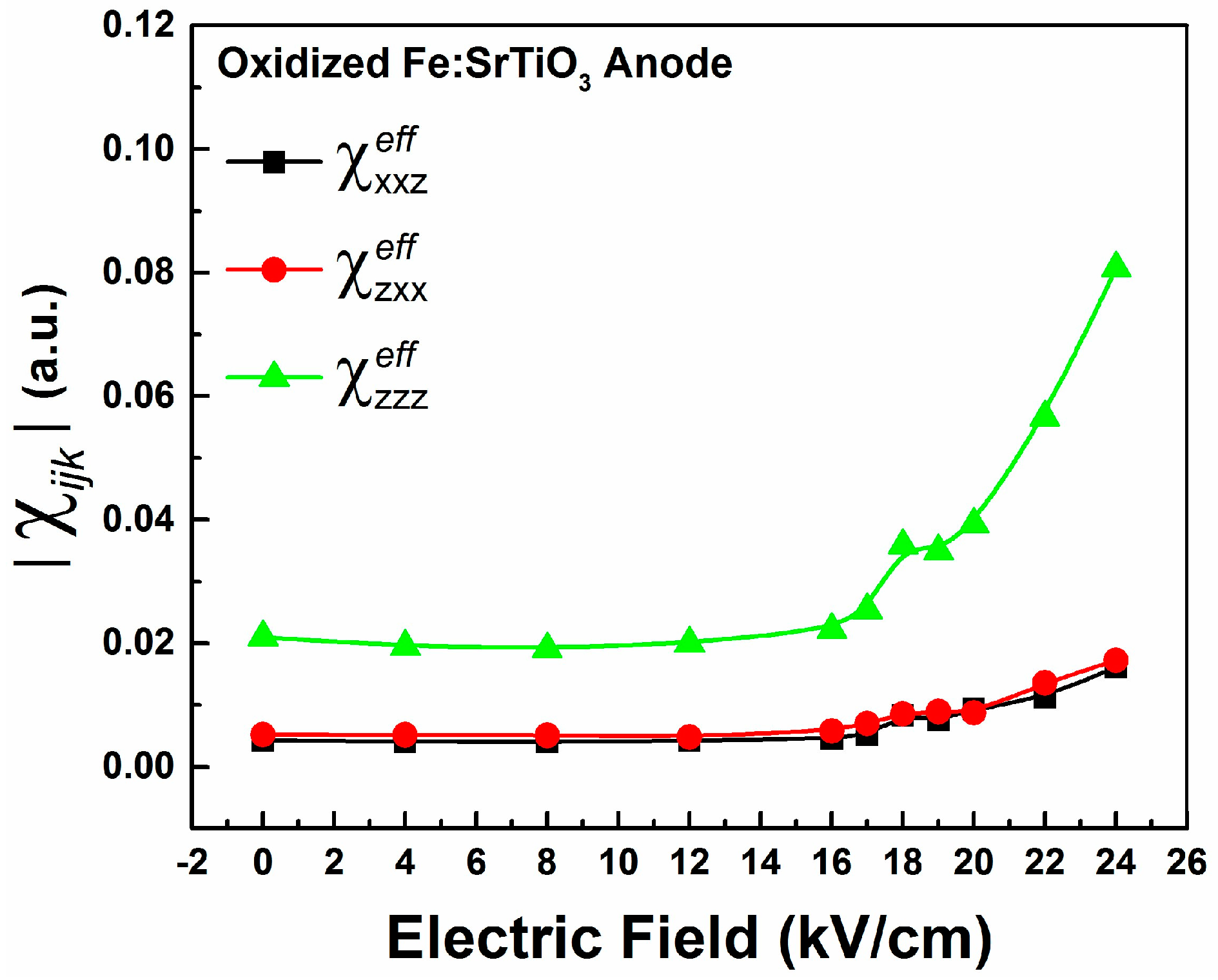

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Buchanan, R.C. Ceramic Materials for Electronics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; Volume 68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yang, G.-Y.; Randall, C.A. Evidence for Increased Polaron Conduction Near the Cathodic Interface in the Final Stages of Electrical Degradation in SrTiO3 Crystals. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 48, 051404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waser, R.; Baiatu, T.; Härdtl, K.H. dc Electrical Degradation of Perovskite-Type Titanates: I, Ceramics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1990, 73, 1645–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waser, R.; Baiatu, T.; Härdtl, K.H. dc Electrical Degradation of Perovskite-Type Titanates: II, Single Crystals. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1990, 73, 1654–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiatu, T.; Waser, R.; Härdtl, K.H. dc Electrical Degradation of Perovskite-Type Titanates: III, A Model of the Mechanism. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1990, 73, 1663–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Dickey, E.; Randall, C.; Randall, M.; Mann, L. Modulated and ordered defect structures in electrically degraded Ni–BaTiO3 multilayer ceramic capacitors. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 94, 5990–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.A.; Metlenko, V.; Park, D.; Weirich, T.E. Behavior of oxygen vacancies in single-crystal SrTiO3: Equilibrium distribution and diffusion kinetics. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 174109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenser, C.; Kalinko, A.; Kuzmin, A.; Berzins, D.; Purans, J.; Szot, K.; Waser, R.; Dittmann, R. Spectroscopic study of the electric field induced valence change of Fe-defect centers in SrTiO3. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 20779–20786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-J.; Huang, H.-B.; Bayer, T.J.; Moballegh, A.; Cao, Y.; Klein, A.; Dickey, E.C.; Irving, D.L.; Randall, C.A.; Chen, L.-Q. Defect chemistry and resistance degradation in Fe-doped SrTiO3 single crystal. Acta Mater. 2016, 108, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölbling, T.; Söylemezoğlu, N.; Waser, R. A Mathematical-Physical Model for the Charge Transport in p-Type SrTiO3 Ceramics Under dc Load: Maxwell-Wagner Relaxation. J. Electroceram. 2002, 9, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, R.A.; Fleig, J.; Merkle, R.; Maier, J. SrTiO3: A Model Electroceramic: Dedicated to Professor Dr. Dr. hc Manfred Rühle on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday. Z. Metallkunde 2003, 94, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Jolly, S.; Xiao, M.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, C.; Zhu, W. Domain microstructures and ferroelectric phase transition in Pb0.35 Sr0.65 TiO3 films studied by second harmonic generation in reflection geometry. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denev, S.A.; Lummen, T.T.; Barnes, E.; Kumar, A.; Gopalan, V. Probing ferroelectrics using optical second harmonic generation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 94, 2699–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, E.; Sherstyuk, N.; Barskiy, D.; Sigov, A.; Golovko, Y.I.; Mukhorotov, V.; De Santo, M.; Rasing, T. Domain orientation in ultrathin (Ba, Sr)TiO3 films measured by optical second harmonic generation. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 6216–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Jin, K.; Guo, H.; Lu, H.; Yang, G. A study on surface symmetry and interfacial enhancement of SrTiO3 by second harmonic generation. Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 2013, 56, 2370–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishina, E.; Misuryaev, T.; Sherstyuk, N.; Lemanov, V.; Morozov, A.; Sigov, A.; Rasing, T. Observation of a near-surface structural phase transition in SrTiO3 by optical second harmonic generation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotter, L.D.; Kaiser, D.L. Detection of internal electric fields in BaTiO3 thin films by optical second harmonic generation. Integr. Ferroelectr. 1998, 22, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascienzo, D.; Greenbaum, S.; Bayer, T.; Maier, R.; Randall, C.; Ren, Y. Observation of structural inhomogeneity at degraded Fe-doped SrTiO3 interfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 031602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.E. Impedance/Thermally Stimulated Depolarization Current and Microstructural Relations at Interfaces in degraded Perovskite Dielectrics. Ph.D. Dissertation, Pennsylvania State Unversity, State College, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Denk, I.; Münch, W.; Maier, J. Partial Conductivities in SrTiO3: Bulk Polarization Experiments, Oxygen Concentration Cell Measurements, and Defect-Chemical Modeling. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1995, 78, 3265–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herger, R.; Willmott, P.; Bunk, O.; Schlepütz, C.; Patterson, B.; Delley, B. Surface of strontium titanate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 076102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubano, A.; Günter, T.; Fink, T.; Paparo, D.; Marrucci, L.; Cancellieri, C.; Gariglio, S.; Triscone, J.-M.; Fiebig, M. Influence of atomic termination on the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interfacial polar rearrangement. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 035405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R.W. Nonlinear Optics; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Paparo, D.; Rubano, A.; Marrucci, L. Optical second-harmonic generation selection rules and resonances in buried oxide interfaces: The case of LaAlO3/SrTiO3. JOSA B 2013, 30, 2452–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubano, A.; Fiebig, M.; Paparo, D.; Marino, A.; Maccariello, D.; di Uccio, U.S.; Granozio, F.M.; Marrucci, L.; Richter, C.; Paetel, S. Spectral and spatial distribution of polarization at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 155405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doig, K.; Peters, J.J.; Nawaz, S.; Walker, D.; Walker, M.; Lees, M.R.; Beanland, R.; Sanchez, A.M.; McConville, C.; Palkar, V. Structural, optical and vibrational properties of self-assembled Pbn+1(Ti1−xFex)nO3n+1−δ Ruddlesden-Popper superstructures. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, B. Bond-charge calculation of nonlinear optical susceptibilities for various crystal structures. Phys. Rev. B 1973, 7, 2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, B. Comment on “Electric-field-induced optical second-harmonic generation in KTaO3 and SrTiO3”. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, Y.; Sakudo, T. Electric-field-induced optical second-harmonic generation in KTaO3 and SrTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 1976, 13, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, D. Nonlinear dielectric polarization in optical media. Phys. Rev. 1962, 126, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lei, Y.; Shen, B.; Sun, J. Visible-light-accelerated oxygen vacancy migration in strontium titanate. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanzig, J.; Zschornak, M.; Hanzig, F.; Mehner, E.; Stöcker, H.; Abendroth, B.; Röder, C.; Talkenberger, A.; Schreiber, G.; Rafaja, D. Migration-induced field-stabilized polar phase in strontium titanate single crystals at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B 2013, 88, 024104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, G.; Rubano, A.; di Gennaro, E.; Khare, A.; Granozio, F.M.; di Uccio, U.S.; Marrucci, L.; Paparo, D. Potential-well depth at amorphous-LaAlO3/crystalline-SrTiO3 interfaces measured by optical second harmonic generation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 261603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| pO2 (bar) | T (°C) | [VO] (cm−3) | [Fe3+] (cm−3) | [Fe4+] (cm−3) | [Fe3+]/[Fe] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 900 | 1.03 × 1018 | 3.28 × 1018 | 2.30 × 1018 | 0.59 |

| 0.2 | 25 | 1.03 × 1018 | 2.06 × 1018 | 2.52 × 1018 | 0.37 |

| 2 × 10−5 | 900 | 2.43 × 1018 | 5.04 × 1018 | 5.44 × 1017 | 0.90 |

| 2 × 10−5 | 25 | 2.43 × 1018 | 4.85 × 1018 | 7.30 × 1017 | 0.87 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ascienzo, D.; Yuan, H.; Greenbaum, S.; Bayer, T.J.M.; Maier, R.A.; Wang, J.-J.; Randall, C.A.; Dickey, E.C.; Zhao, H.; Ren, Y. Investigation of Electric Field–Induced Structural Changes at Fe-Doped SrTiO3 Anode Interfaces by Second Harmonic Generation. Materials 2016, 9, 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9110883

Ascienzo D, Yuan H, Greenbaum S, Bayer TJM, Maier RA, Wang J-J, Randall CA, Dickey EC, Zhao H, Ren Y. Investigation of Electric Field–Induced Structural Changes at Fe-Doped SrTiO3 Anode Interfaces by Second Harmonic Generation. Materials. 2016; 9(11):883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9110883

Chicago/Turabian StyleAscienzo, David, Haochen Yuan, Steve Greenbaum, Thorsten J. M. Bayer, Russell A. Maier, Jian-Jun Wang, Clive A. Randall, Elizabeth C. Dickey, Haibin Zhao, and Yuhang Ren. 2016. "Investigation of Electric Field–Induced Structural Changes at Fe-Doped SrTiO3 Anode Interfaces by Second Harmonic Generation" Materials 9, no. 11: 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma9110883