Enhanced Photocatalytic Efficiency of N–F-Co-Embedded Titania under Visible Light Exposure for Removal of Indoor-Level Pollutants

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

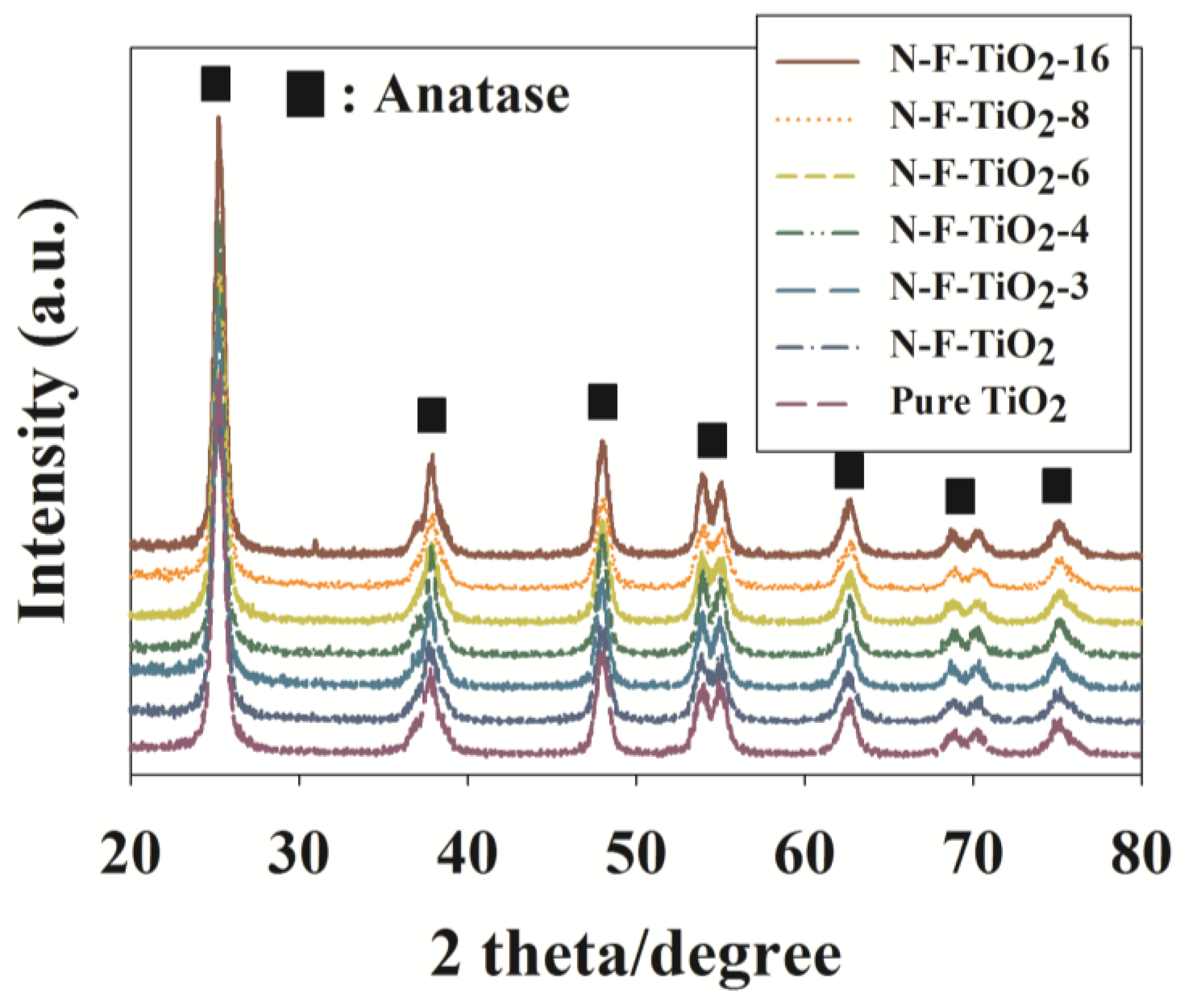

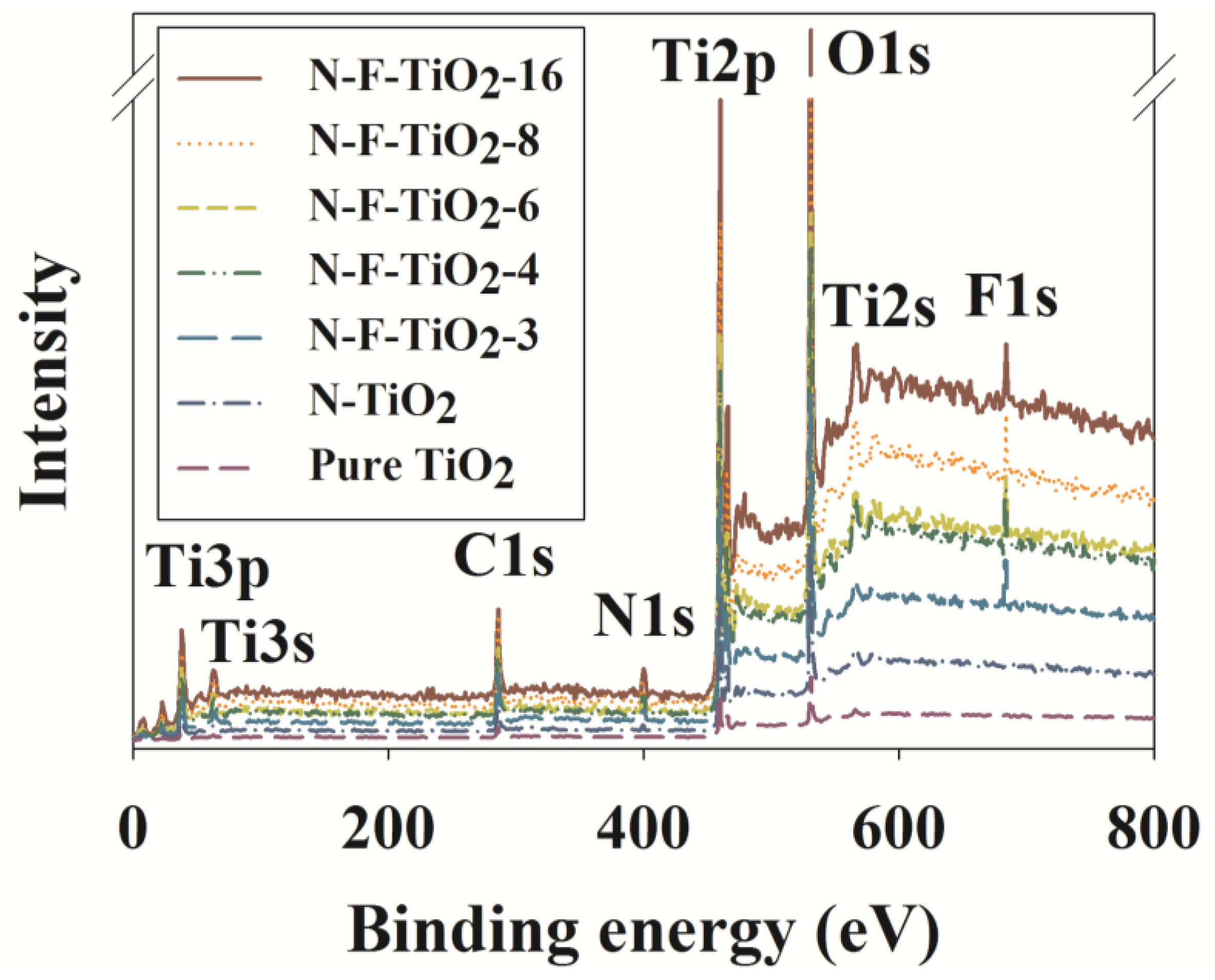

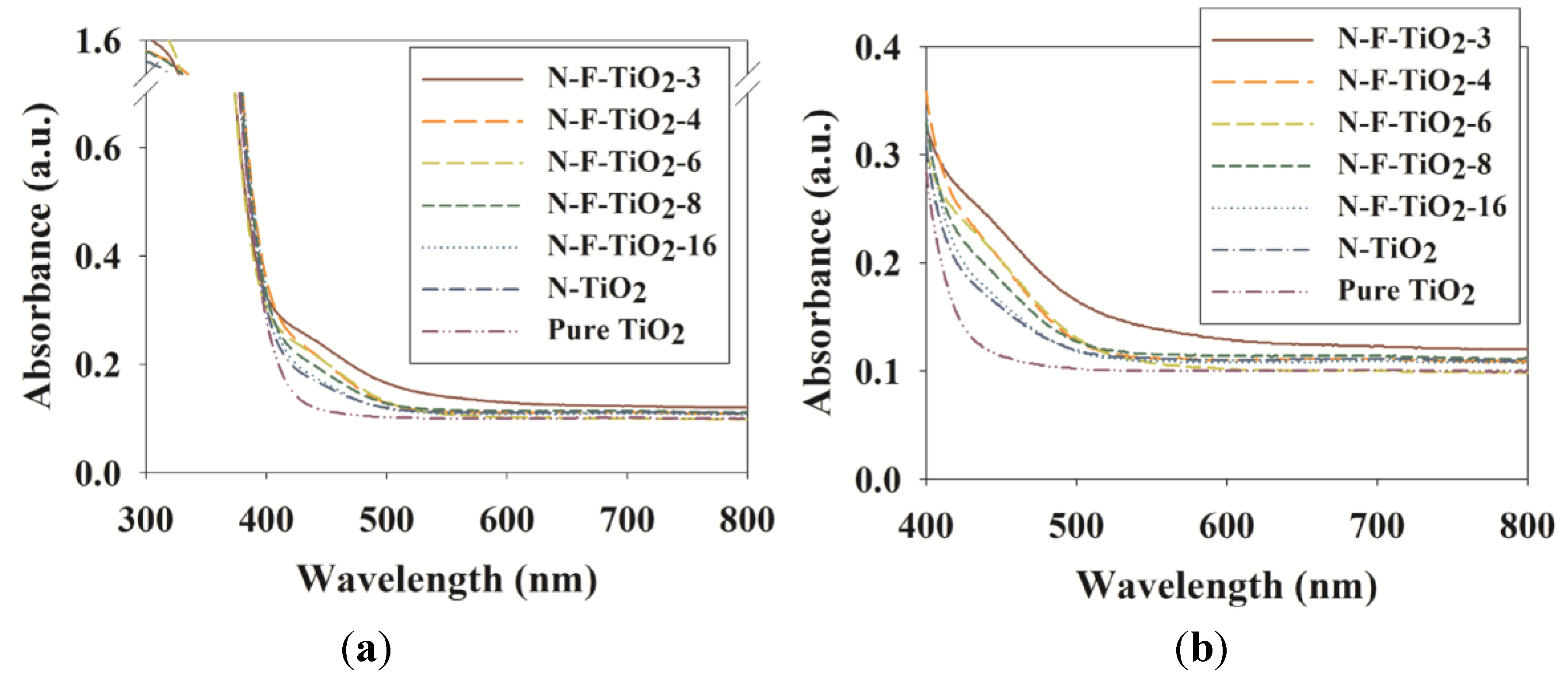

2.1. Characteristics of Prepared Photocatalysts

| Photocatalyst | Ti2p | Ti3p | Ti2s | Ti3s | O1s | N1s | F1s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N–F–TiO2-16 | 459.9 | 37.7 | 566.1 | 62.6 | 529.8 | 399.4 (7.2) | 684.1 (0.4) |

| N–F–TiO2-8 | 459.9 | 37.7 | 567.2 | 62.6 | 529.4 | 399.2 (6.9) | 683.1 (0.8) |

| N–F–TiO2-6 | 459.9 | 37.7 | 565.5 | 61.5 | 529.2 | 399.4 (7.0) | 683.9 (1.3) |

| N–F–TiO2-4 | 459.7 | 37.7 | 566.2 | 62.6 | 529.2 | 399.4 (7.4) | 683.1 (1.7) |

| N–F–TiO2-3 | 459.1 | 37.7 | 566.1 | 62.9 | 529.4 | 399.4 (6.8) | 683.9 (2.1) |

| N–TiO2 | 459.1 | 37.7 | 567.1 | 62.6 | 529.8 | NA | NA |

| pure TiO2 | 459.7 | 37.7 | 566.1 | 62.8 | 529.8 | NA | NA |

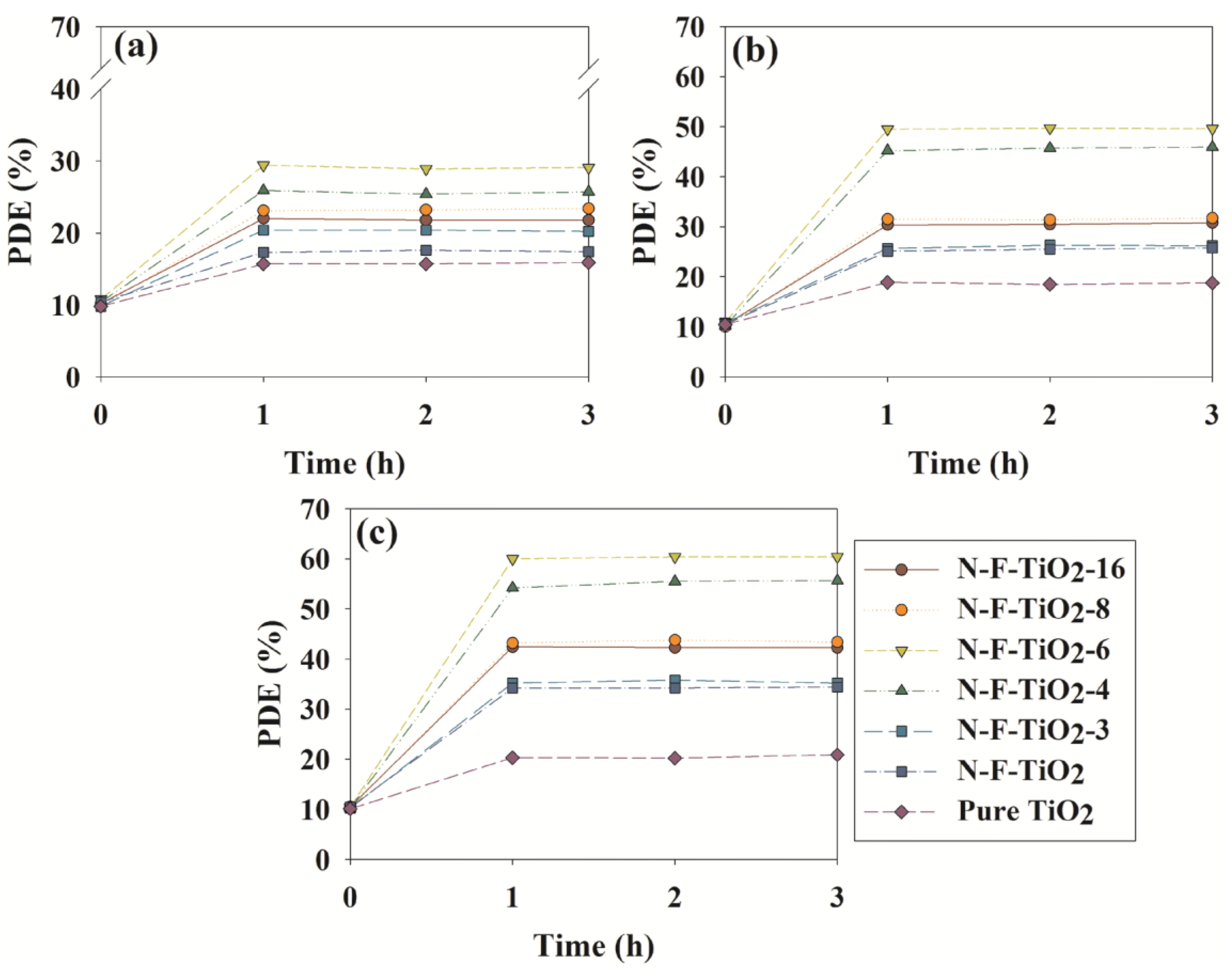

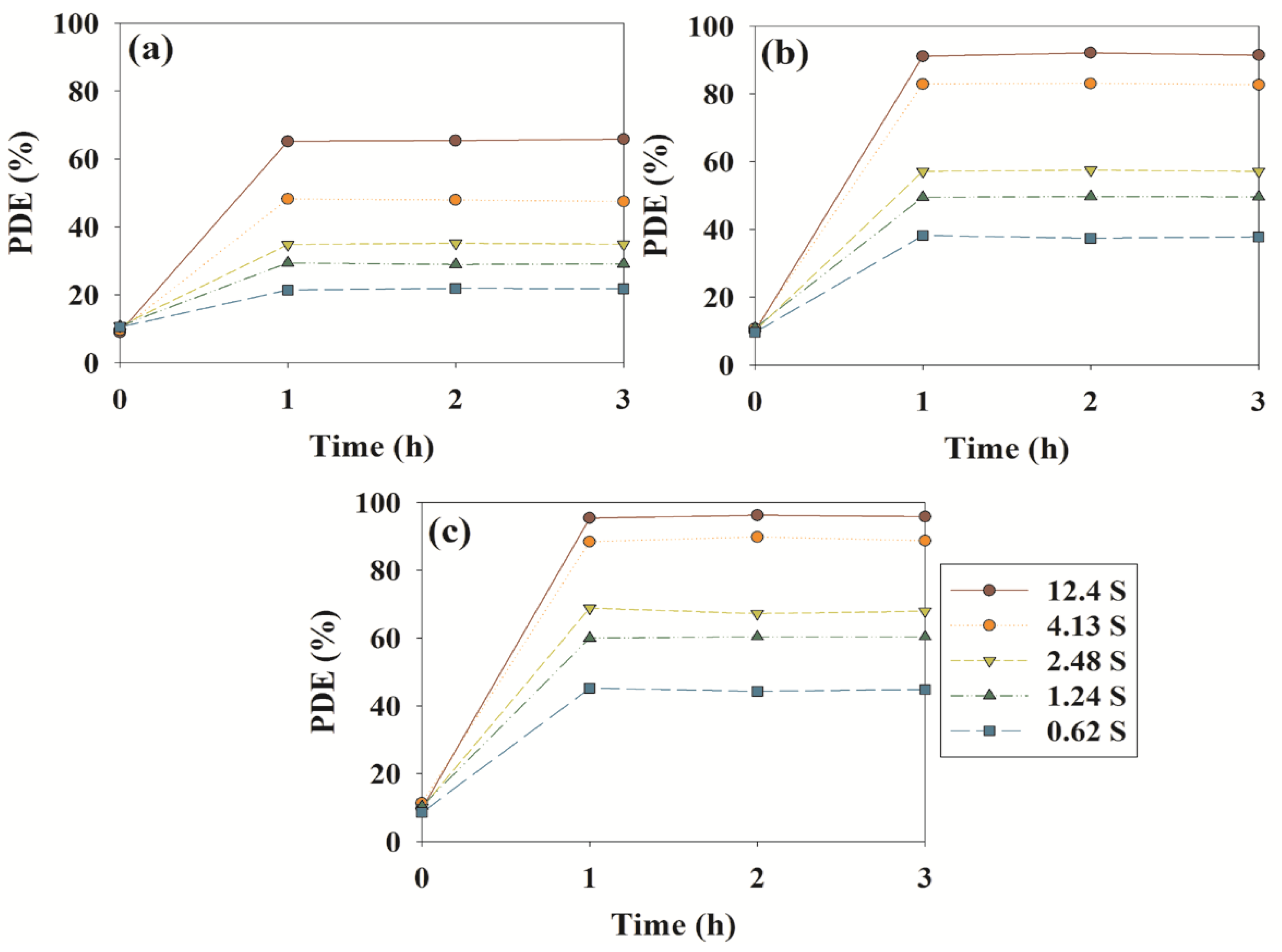

2.2. Photocatalytic Activities of N–F–TiO2, N–TiO2 and Pure TiO2

| Compound | Retention Time (s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.62 | 1.24 | 2.48 | 4.13 | 12.4 | |

| Toluene | 1.0 × 10−3 | 0.7 × 10−3 | 0.4 × 10−3 | 0.3 × 10−3 | 0.2 × 10−3 |

| Ethyl benzene | 1.8 × 10−3 | 1.2 × 10−3 | 0.7 × 10−3 | 0.5 × 10−3 | 0.2 × 10−3 |

| o-Xylene | 2.1 × 10−3 | 1.4 × 10−3 | 0.8 × 10−3 | 0.5 × 10−3 | 0.2 × 10−3 |

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Photocatalysts

3.2. Tests for Photocatalytic Activity

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nakata, K.; Fujishima, A. TiO2 photocatalysis: Design and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2012, 13, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, L.G.; Kavitha, R. A review on non metal ion doped titania for the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants under UV/solar light: Role of photogenerated charge carrier dynamics in enhancing the activity. Appl. Catal. B 2013, 140–141, 559–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M.A. A surface science perspective on TiO2 photocatalysis. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2011, 66, 185–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Kemell, M.; Heikkilä, M.; Leskelä, M. Noble metal-modified TiO2 thin film photocatalyst on porous steel fiber support. Appl. Catal. B 2010, 95, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kment, S.; Kmentova, H.; Kluson, P.; Krysa, J.; Hubicka, Z.; Cirkva, V.; Gregora, I.; Solcova, O.; Jastrabik, L. Notes on the photo-induced characteristics of transition metal-doped and undoped titanium dioxide thin films. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2010, 348, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, T.; Akiyoshi, M.; Umebayashi, T.; Asai, K.; Mitsui, T.; Matsumura, M. Preparation of S-doped TiO2 photocatalysts and their photocatalytic activities under visible light. Appl. Catal. A 2004, 265, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, S.; Ang, H.M.; Tadé, M.O.; Li, Q. Halogen element modified titanium dioxide for visible light photocatalysts. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 162, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, J.; García, A.; Zhao, L.; Titirici, M.M. Solvothermal carbon-doped TiO2 photocatalyst for the enhanced methylene blue degradation under visible light. Appl. Catal. A 2010, 390, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-C.; Hsu, T.-C.; Lu, S.-Y. Effect of nitrogen doping on the microstructure and visible light photocatalysis of titanate nanotubes by a facile cohydrothermal synthesis via urea treatment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 280, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Valentin, C.; Finazzi, E.; Pacchioni, G.; Selloni, A.; Livraghi, S.; Paganini, M.C.; Giamello, E. N-doped TiO2: Theory and experiment. Chem. Phys. 2007, 338, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaez, M.; Nolan, N.T.; Pillai, S.C.; Seery, M.K.; Falaras, P.; Kontos, A.G.; Dunlop, P.S.M.; Hamilton, J.W.J.; Byrne, J.A.; O’Shea, K.; et al. A review on the visible light active titanium dioxide photocatalysts for environmental applications. Appl. Catal. B 2012, 125, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahi, R.; Morikawa, T.; Ohwaki, T.; Aoki, K.; Taga, Y. Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides. Science 2001, 293, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Xing, M.; Tian, B.; Zhang, J.; Chen, F. Preparation of nitrogen and fluorine co-doped mesoporus TiO2 microsphere and photodegradation of acid orange 7 under visible light. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 162, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, F.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.-M. Drastically enhanced photocatalytic activity in nitrogen doped mesoporous TiO2 with abundant surface states. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 334, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, W.K.; Kim, J.T. Application of visible-light photocatalysis with nitrogen-doped or unmodified titanium dioxide for control of indoor-level volatile organic compounds. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 164, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurkan, Y.Y.; Turkten, N.; Hatipoglu, A.; Cinar, Z. Photocatalytic degradation of cefazolin over N-doped TiO2 under UV and sunlight irradiation: Prediction of the reaction paths via conceptual DFT. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 184, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Quan, H.; Ye, J. Photocatalytic properties and photoinduced hydrophilicity of surface-Fluorinated TiO2. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhou, G.; Liu, S.; Ang, H.M.; Tadé, M.O.; Wang, S. Visible light responsive titania photocatalysts codoped by nitrogen and metal (Fe, Ni, Ag, or Pt) for remediation of aqueous pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 231, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Valentin, C.; Finazzi, E.; Pacchioni, G. Density functional theory and electron paramagnetic resonance study on the effect of N–F codoping of TiO2. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 3706–3714. [Google Scholar]

- Pelaez, M.; de la Cruz, A.A.; Stathatos, E.; Falaras, P.; Dionysiou, D.D. Visible light-activated N–F-codoped TiO2 nanoparticles for the photocatalytic degradation of microcystin-LR in water. Catal. Today 2009, 144, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.L.; Anpo, M. Carbon and nitrogen-codoped TiO2 with high visible light photocatalytic activity. Chem. Lett. 2006, 35, 800–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Ullah, R.; Chong, S.; Ang, H.M.; Tadé, M.O.; Wang, S. Room-light-induced indoor air purification using an efficient Pt/N-TiO2 photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B 2011, 108–109, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Wen, J.; Nigro, S.; Chen, A. One-step synthesis of N- and F-codoped mesoporus TiO2 photocatalysts with high visible light activity. Nanotechnology 2010, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, A.; Zhang, X.; Tryk, D.A. TiO2 photocatalysis and related surface phenomena. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2008, 63, 515–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlink, U.; Thiem, A.; Kohajda, T.; Richter, M.; Strebel, K. Quantile regression of indoor air concentrations of volatile organic compounds (VOC). Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 3840–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- USEPA. An Introduction to Indoor Air Quality: Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). Available online: http://www.epa.gov/iaq/voc.html (accessed on 11 December 2012).

- Sun, S.; Ding, J.; Bao, J.; Gao, C.; Qi, Z.; Yang, X.; He, B.; Li, C. Photocatalytic degradation of gaseous toluene on Fe–TiO2 under visible light irradiation: A study on the structure, activity and deactivation mechanism. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 5031–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Haneda, H.; Hishita, S.; Ohashi, N. Visible-light-deriven NF-codoped TiO2 photocatalysts. 2. Optical characterization, photocatalysis, and potential application to air purification. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 2596–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, W.K.; Kang, H.J. Polyacrylonitrile-TiO2 fibers for control of gaseous aromatic compounds. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 4475–4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.-P.; Lee, G.W.M.; Huang, W.-M.; Wu, C.; Yang, S. The correlation between photocatalytic performance and chemical/physical properties of indoor volatile organic compounds. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, S.-H.; Chun, H.-H.; Jo, W.-K. Enhanced Photocatalytic Efficiency of N–F-Co-Embedded Titania under Visible Light Exposure for Removal of Indoor-Level Pollutants. Materials 2015, 8, 31-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8010031

Shin S-H, Chun H-H, Jo W-K. Enhanced Photocatalytic Efficiency of N–F-Co-Embedded Titania under Visible Light Exposure for Removal of Indoor-Level Pollutants. Materials. 2015; 8(1):31-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Seung-Ho, Ho-Hwan Chun, and Wan-Kuen Jo. 2015. "Enhanced Photocatalytic Efficiency of N–F-Co-Embedded Titania under Visible Light Exposure for Removal of Indoor-Level Pollutants" Materials 8, no. 1: 31-41. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma8010031