Th(IV) Adsorption onto Oxidized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in the Presence of Hydroxylated Fullerene and Carboxylated Fullerene

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

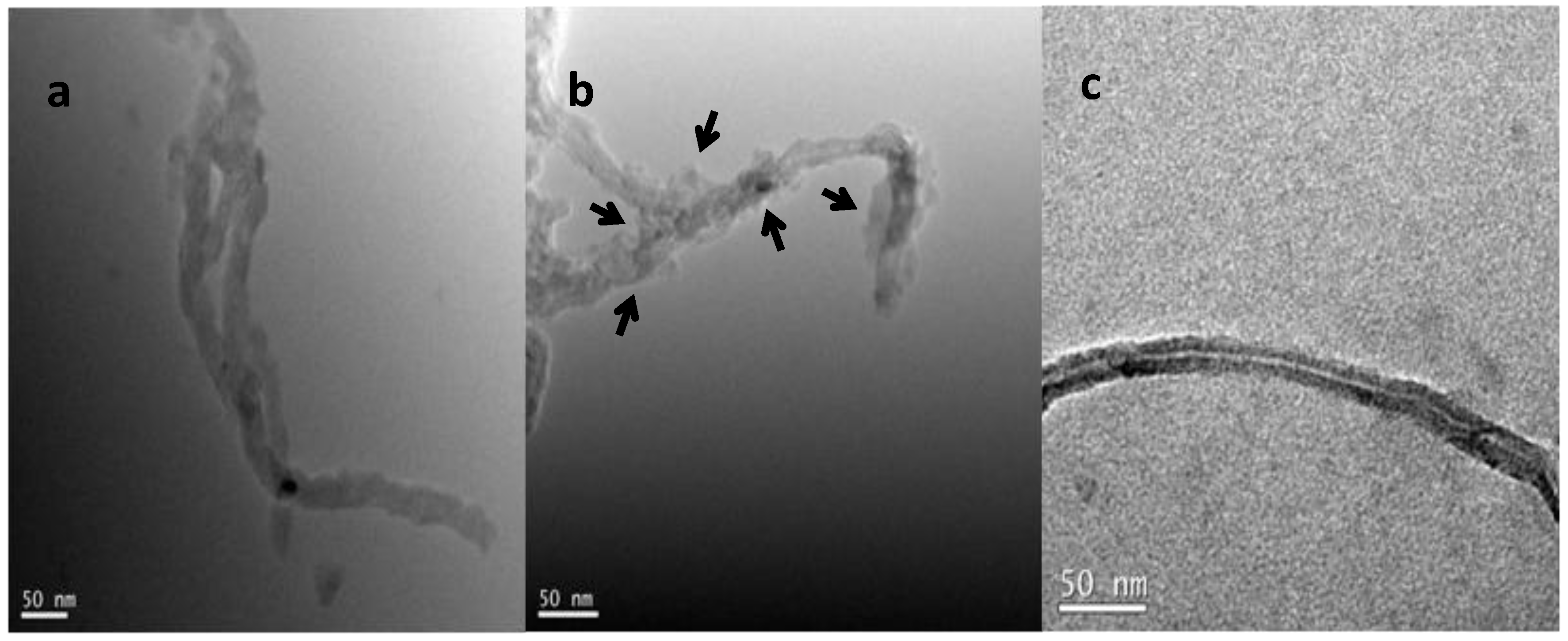

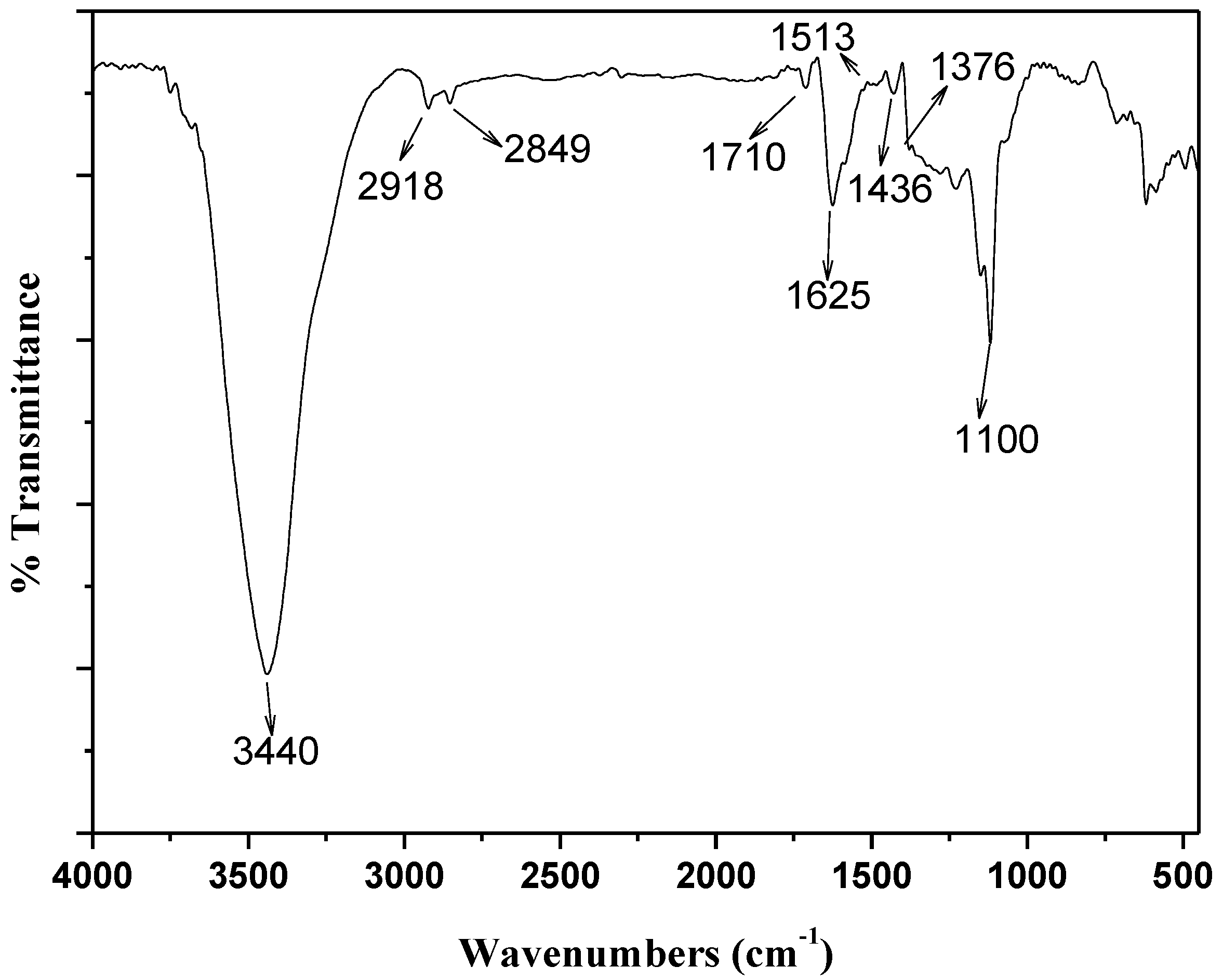

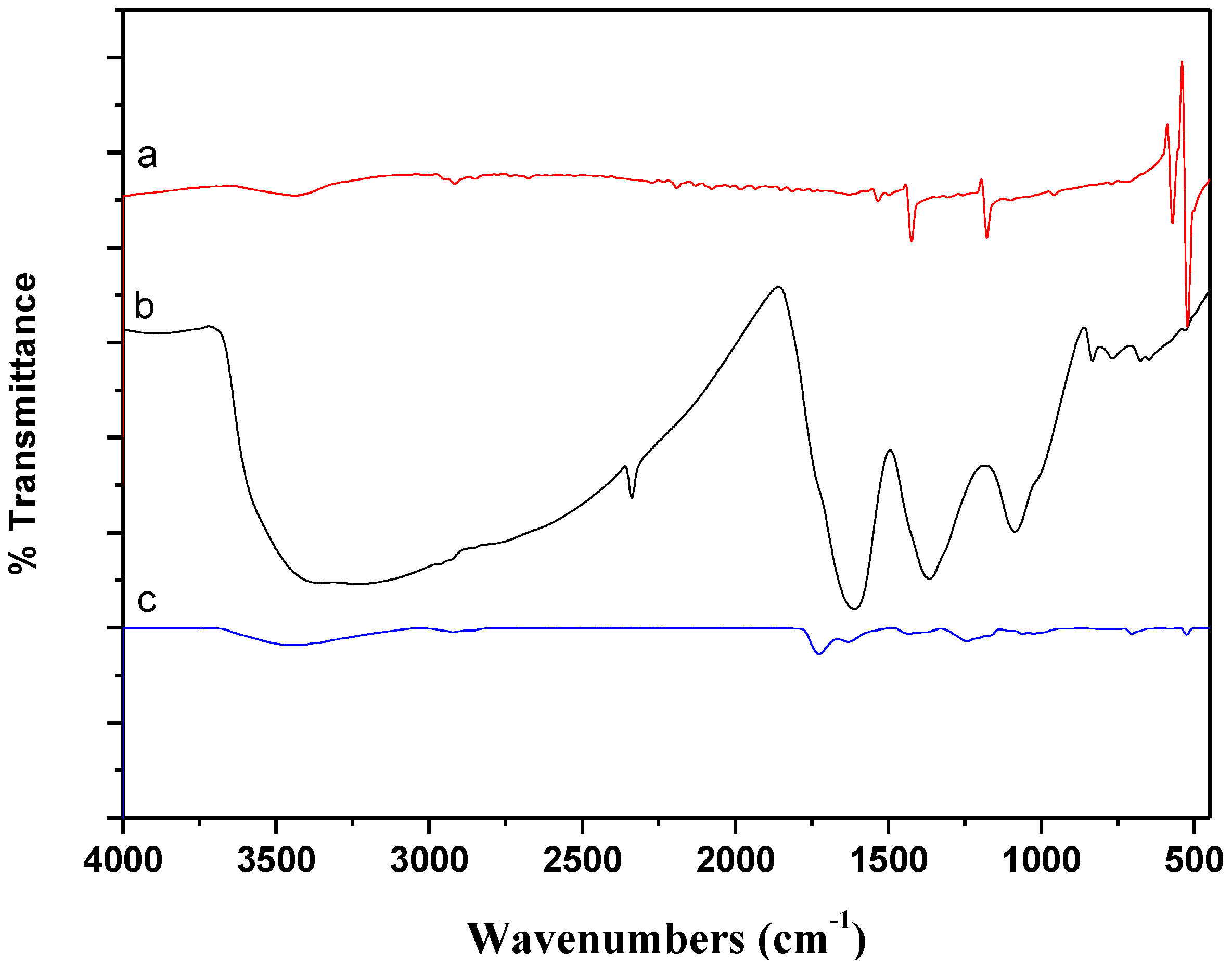

2.1. Characterization of Purified oMWCNTs, C60(OH)n and C60(C(COOH)2)n

2.2. Adsorption of Th(IV) onto oMWNTs Surface

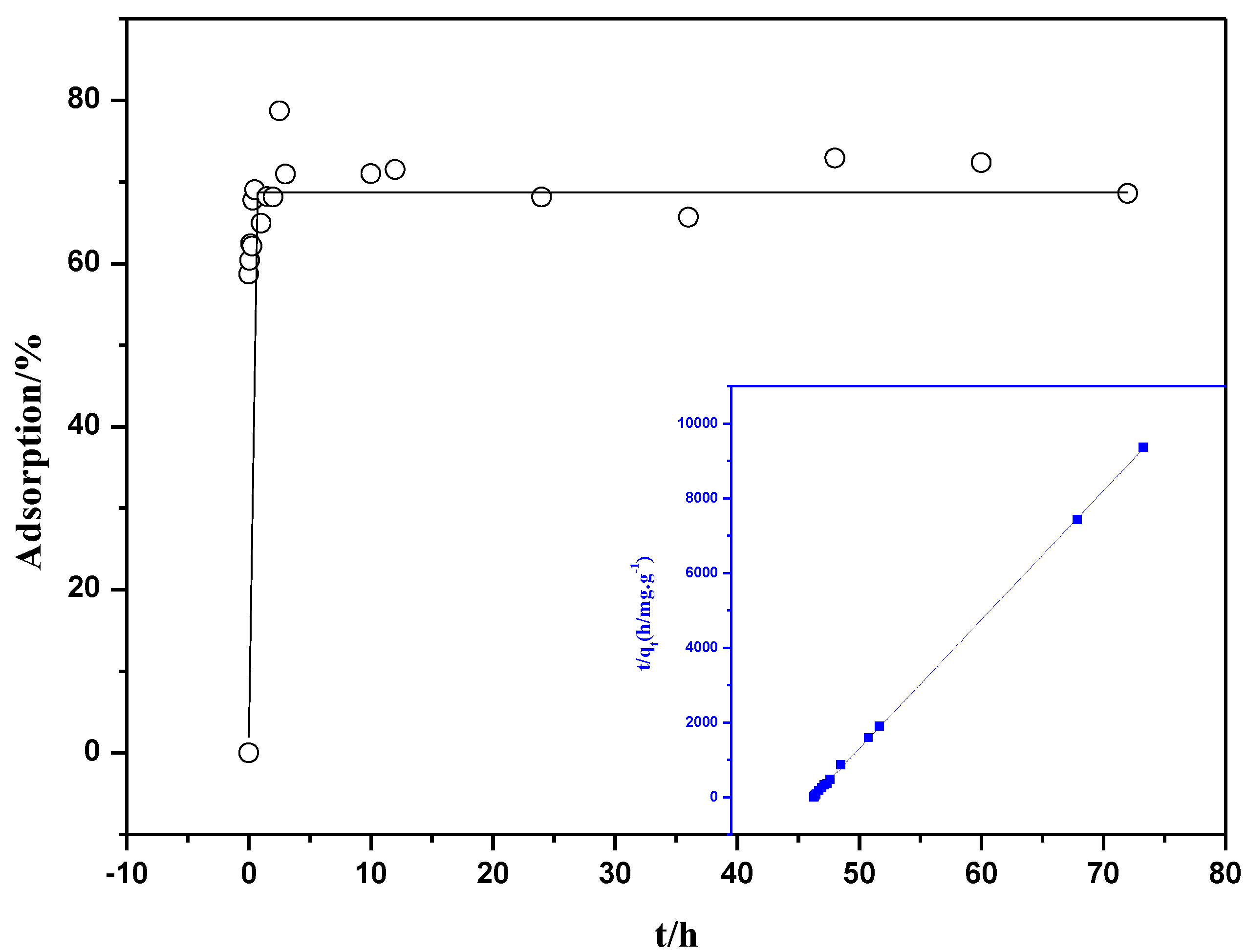

2.2.1. The Sorption Kinetics

2.2.2. Influence of pH and Ionic Strength

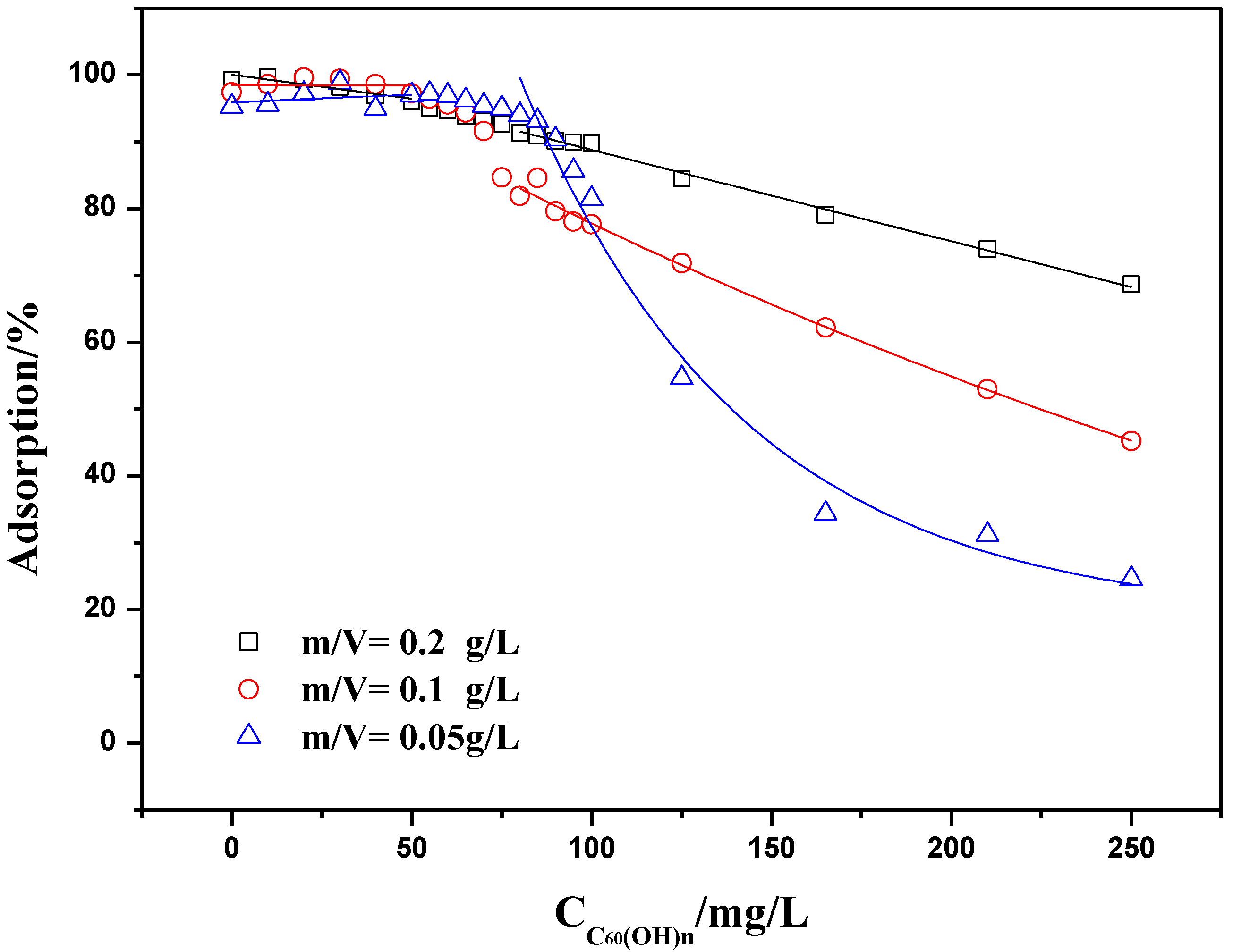

2.2.3. Influence of the Concentration of oMWCNTs

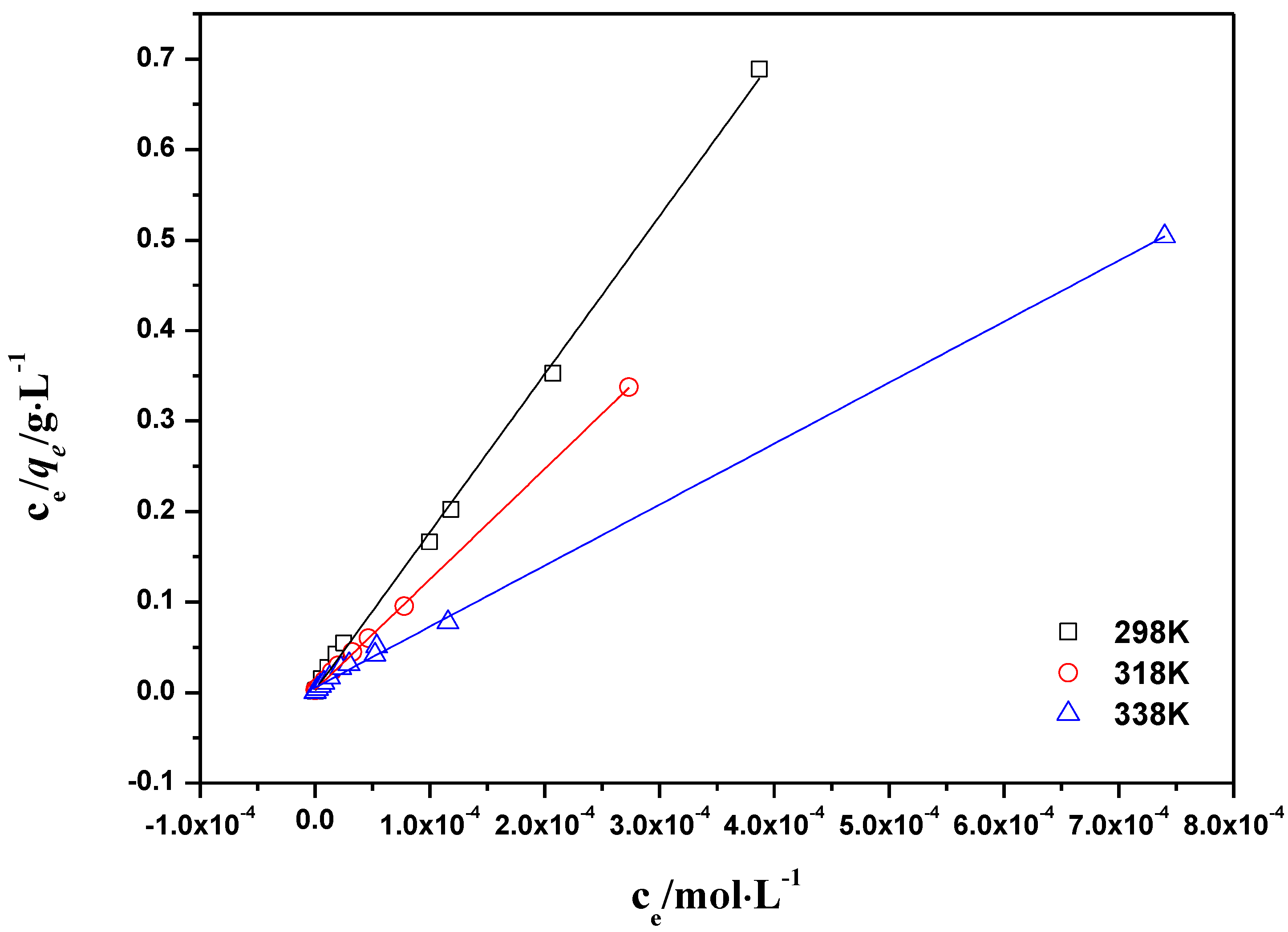

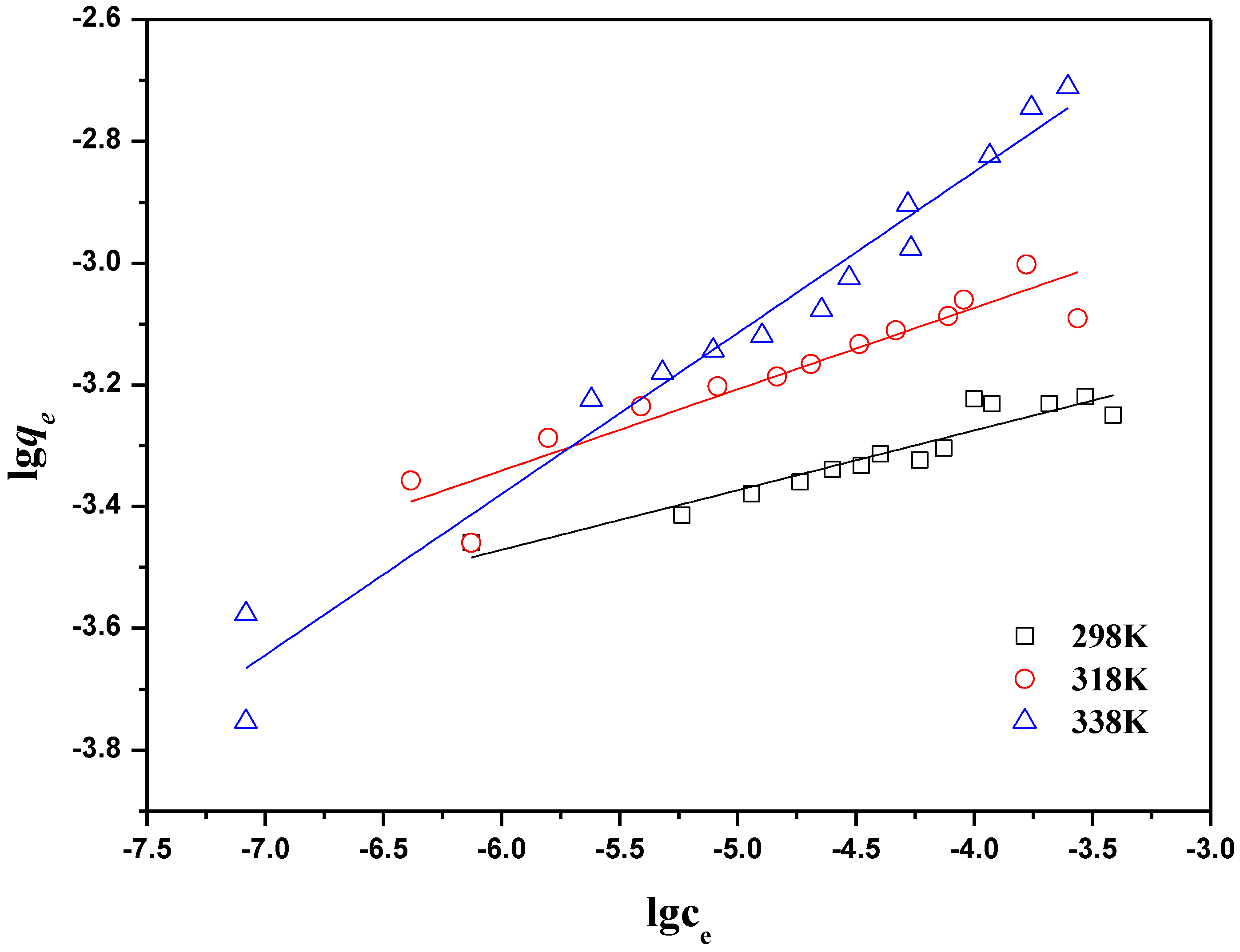

2.2.4. Adsorption Isotherms

| T(K) | Langmuir constants | Freundlich constants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qmax (mg·g−1) | KL | R2 | KF (mg1−n·Ln·g−1) | n | R2 | |

| 298 | 5.72× 10−4 | 423.7 | 0.998 | 1.31× 10−3 | 0.09 | 0.887 |

| 318 | 8.18× 10−4 | 359.7 | 0.999 | 2.89× 10−3 | 0.13 | 0.881 |

| 338 | 1.48× 10−3 | 185.2 | 0.998 | 1.62× 10−3 | 0.26 | 0.969 |

| C0 (mg·L−1) | ΔH0 (KJ·mol−1) | ΔS0 (J·mol−1·K−1) | ΔG0 (KJ·mol−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 298 K | 318 K | 338 K | |||

| 7.09 × 10−5 | 42.65 | 168.12 | −7.19 | −11.47 | −13.84 |

| 7.98 × 10−5 | 39.52 | 154.88 | −6.53 | −10.03 | −12.69 |

| 8.87 × 10−5 | 33.67 | 134.09 | −6.17 | −9.28 | −11.51 |

| 1.06 × 10−4 | 32.15 | 125.75 | −5.17 | −8.23 | −10.15 |

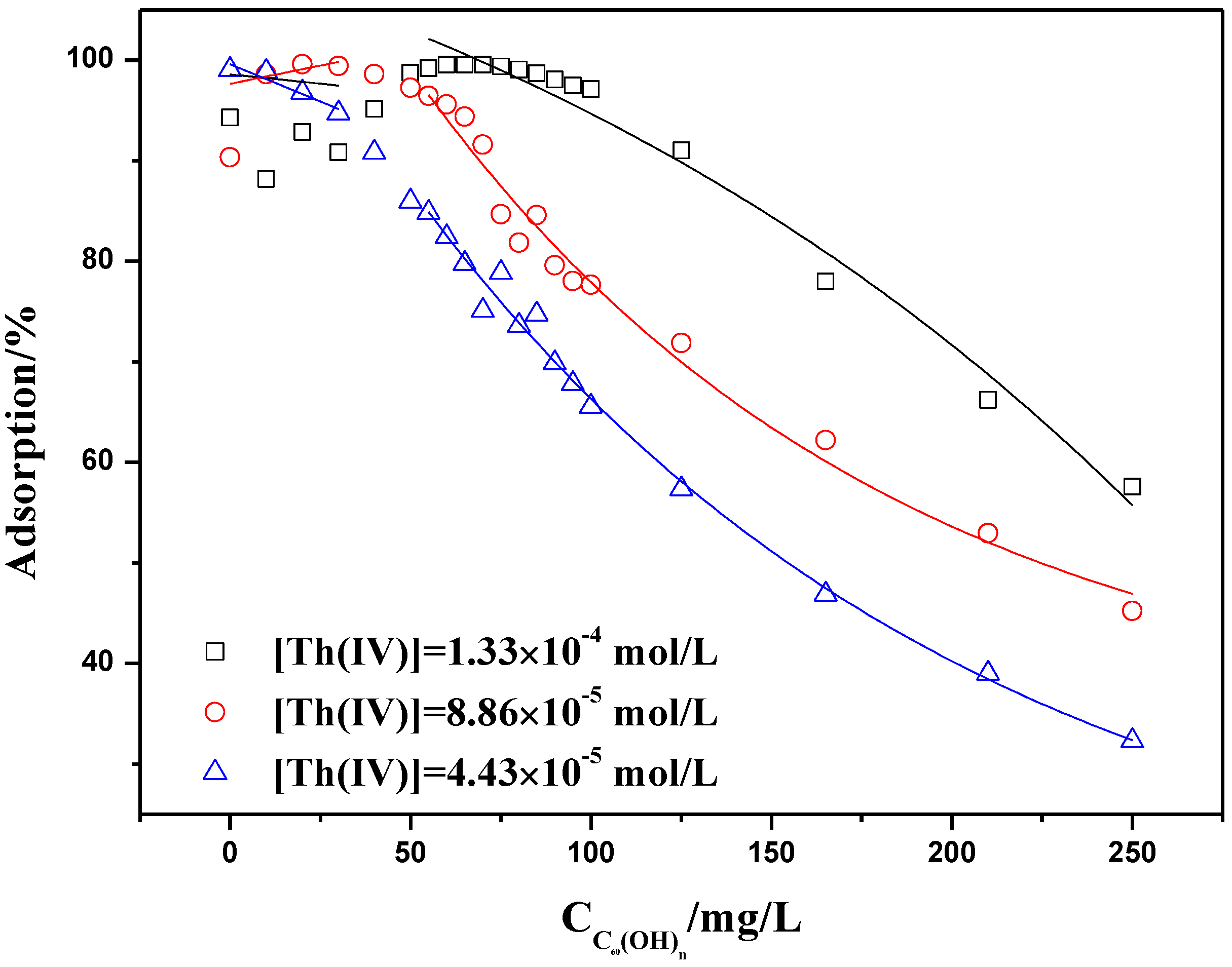

2.3. Influence of C60(OH)n on the Adsorption of Th(IV)

2.3.1. Adsorption of Th(IV) vs. pH in the Presence of C60(OH)n

2.3.2. Adsorption Isotherms at Constant Adsorbent Dose and Initial Concentration

2.4. Influence of C60(C(COOH)2)n on Th(IV) Adsorption

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

3.2. Adsorption Experiments

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Appendix

References

- Balasubramanian, K.; Burghard, M. Chemically Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes. Small 2005, 1, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datsyuk, V.; Kalyva, M.; Papagelis, K.; Parthenios, J.; Tasis, D.; Siokou, A.; Kallitsis, I.; Galiotis, C. Chemical oxidation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2008, 46, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilding, J.; Grulke, E.A.; Zhang, Z.G.; Lockwood, F. Dispersion of carbon nanotubes in liquids. J. Disper. Sci. Technol. 2003, 24, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, C.M.; Saridara, C.; Mitra, S. Microtrapping characteristics of single and multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1185, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Zhao, D.; Tan, X.; Wang, X. Adsorption kinetic, thermodynamic and desorption studies of Th(IV) on oxidized multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 302, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Hu, W.; Ding, A.; Xu, D.; Zhou, X. Sorption of 243Am(III) to Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 2856–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Hu, J.; Xu, D.; Tan, X.; Meng, Y.; Wang, X. Surface complexation modeling of Sr(II) and Eu(III) adsorption onto oxidized multiwall carbon nanotubes. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2008, 323, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, B.; Bucheli, T.D. Occurrence, behavior and effects of nanoparticles in the environment. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 150, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoren, M.; Herzog, E.; Casey, A.; Cottineau, B.; Chambers, G.; Byrne, H.J.; Lyng, F.M. In vitro toxicity evaluation of single walled carbon nanotubes on human A549 lung cells. Toxicol Vitro 2007, 21, 438–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Deckers, A.; Gouget, B.; Mayne-L’Hermite, M.; Herlin-Boime, N.; Reynaud, C.; Carrière, M. In vitro investigation of oxide nanoparticle and carbon nanotube toxicity and intracellular accumulation in A 549 human pneumocytes. Toxicology 2008, 253, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Q.H.; Shao, D.D.; Hu, J.; Chen, C.; Wu, W.; Wang, X. Adsorption of humic acid and Eu (III) to multi-walled carbon nanotubes: Effect of pH, ionic strength and counterion effect. Radiochim. Acta 2009, 97, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, C.S.K.; Subramanian, M. DAPPA grafted polymer: an efficient solid phase extractant for U (VI), Th (IV) and La (III) from acidic waste streams and environmental samples. Talanta 2005, 67, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, V.; Pandya, R.; Pillai, S.; Shrivastav, P. Simultaneous preconcentration of uranium (VI) and thorium (IV) from aqueous solutions using a chelating calix[4]arene anchored chloromethylated polystyrene solid phase. Talanta 2006, 70, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydin, F.A.; Soylak, M. Solid phase extraction and preconcentration of uranium(VI) and thorium(IV) on Duolite XAD761 prior to their inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric determination. Talanta 2007, 72, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkhedda, K.; Epov, V.N.; Evans, R.D. Flow-injection technique for determination of uranium and thorium isotopes in urine by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005, 381, 1596–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- östhols, E.; Manceau, A.; Farges, F.; Charlet, L. Adsorption of Thorium on Amorphous Silica: An EXAFS Study. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 1997, 194, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Wang, X.K. Influence of pH, soil humic/fulvic acid, ionic strength and foreign ions on sorption of thorium(IV) onto γ-Al2O3. Appl. Geochem. 2007, 22, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Yu, S.; Zhou, H.; Tian, X.; Jiang, J. Th(IV) adsorption on mesoporous molecular sieves: effects of contact time, solid content, pH, ionic strength, foreign ions and temperature. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2011, 288, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursali, E.A.; Merdivan, M.; Yurdakoc, M. Preconcentration of uranium (VI) and thorium (IV) from aqueous solutions using low-cost abundantly available sorbent. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2010, 283, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Wang, X.K.; Nagatsu, M. Europium Adsorption on Multiwall Carbon Nanotube/Iron Oxide Magnetic Composite in the Presence of Polyacrylic Acid. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 2362–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Yang, S.; Sheng, G.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X. The removal of U(VI) from aqueous solution by oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J. Environ. Radioactiv. 2012, 105, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühl, M.; Hirsch, A. Spherical aromaticity of fullerenes. Chem. Rev. 2001, 101, 1153–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montes-Morán, M.A.; Suárez, D.; Menéndez, J.A.; Fuente, E. On the nature of basic sites on carbon surfaces: an overview. Carbon 2004, 42, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avilés, F.; Cauich-Rodríguez, J.V.; Moo-Tah, L.; May-Pat, A.; Vargas-Coronado, R. Evaluation of mild acid oxidation treatments for MWCNT functionalization. Carbon 2009, 47, 2970–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Liu, C.; Rao, G.P. Comparisons of sorbent cost for the removal of Ni2+ from aqueous solution by carbon nanotubes and granular activated carbon. J. Hazard Mater. 2008, 151, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.Y.; Han, K.; Li, S.X.; Cheng, J.S.; Xu, G.T.; Li, W.X.; Li, Q.N. Pulmonary responses to polyhydroxylated fullerenols, C60(OH)x. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2009, 29, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Yang, X.; Zhu, H.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y. Synthesis of oligoadducts of malonic acid C60 and their scavenging effects on hydroxyl radical. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2000, 61, 1145–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wang, S.; Yang, S.; Li, J. Influence of contact time, pH, soil humic/fulvic acids, ionic strength and temperature on sorption of U(VI) onto MX-80 bentonite. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2010, 283, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S. Adsorption of heavy metals from waste streams by peat. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Wang, X.; Fang, M.; Chen, C. Sorption and desorption of Th(IV) on nanoparticles of anatase studied by batch and spectroscopy methods. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2007, 296, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, X. Sorption of Th (IV) to silica as a function of pH, humic/fulvic acid, ionic strength, electrolyte type. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2007, 65, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sheng, G.; Hu, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. The adsorption of Pb(II) on Mg2Al layered double hydroxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Li, J.; Shao, D.; Hu, J.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Adsorption of copper(II) on multiwalled carbon nanotubes in the absence and presence of humic or fulvic acids. J. Hazard Mater. 2010, 178, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Sun, A. Effect of soil humic and fulvic acids, pH and ionic strength on Th(IV) sorption to TiO2 nanoparticles. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2007, 65, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choppin, G. Actinide speciation in the environment. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2007, 273, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anirudhan, T.S.; Rijith, S.; Tharun, A.R. Adsorptive removal of thorium(IV) from aqueous solutions using poly(methacrylic acid)-grafted chitosan/bentonite composite matrix: Process design and equilibrium studies. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2010, 368, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.; Hu, J.; Wang, X. Sorption properties of Th(IV) on the raw diatomite—Effects of contact time, pH, ionic strength and temperature. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2008, 66, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X. Sorption of Ni(II) on GMZ bentonite: Effects of pH, ionic strength, foreign ions, humic acid and temperature. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2009, 67, 1600–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ren, A.; Cheng, J.; Song, X.; Chen, C.; Wang, X. Comparative study on sorption of radiocobalt to montmorillonite and its Al-pillared and cross-linked samples: Effect of pH, ionic strength and fulvic acid. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2007, 273, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, M.; Baeyens, B. Sorption of Eu on Na-and Ca-montmorillonites: Experimental investigations and modelling with cation exchange and surface complexation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 2002, 66, 2325–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X. Sorption and desorption of radioselenium on calcareous soil and its solid components studied by batch and column experiments. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2005, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Fan, Q.; Xu, J.; Niu, Z.; Lu, S. Sorption-desorption of Th(IV) on attapulgite: Effects of pH, ionic strength and temperature. Appl. Radiat. Isotopes 2007, 65, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talip, Z.; Eral, M.; Hiçsönmez, Ü. Adsorption of thorium from aqueous solutions by perlite. J. Environ. Radioactiv. 2009, 100, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiller, P.; Moulin, V.; Casanova, F.; Dautel, C. Retention behaviour of humic substances onto mineral surfaces and consequences upon thorium (IV) mobility: case of iron oxides. Appl. Geochem. 2002, 17, 1551–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhijun, G.; Lijun, N.; Zuyi, T. Sorption of Th(IV) ions onto TiO2: Effects of contact time, ionic strength, thorium concentration and phosphate. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2005, 266, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.M.; Chen, C.L.; Chang, P.P.; Wang, T.T.; Lu, S.S.; Wang, X.K. Adsorption of Th(IV) onto Al-pillared rectorite: Effect of pH, ionic strength, temperature, soil humic acid and fulvic acid. Appl. Clay. Sci. 2008, 38, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Duan, L.; Wang, L.; Zhu, D. Adsorption of Hydroxyl- and Amino-Substituted Aromatics to Carbon Nanotubes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 6862–6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.T.; Guo, W.; Lin, Y.; Deng, X.Y.; Wang, H.F.; Sun, H.F.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, X.; Wang, W.; Chen, M.; et al. Biodistribution of Pristine Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in Vivo. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 17761–17764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Duan, L.; Zhu, D. Adsorption of Polar and Nonpolar Organic Chemicals to Carbon Nanotubes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 8295–8300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Li, X.; Huang, K.; Jiang, H.; Li, J. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxylated fullerene epoxide—An intermediate for forming fullerol. J. Cent. South Univ. T 1999, 6, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Meng, H.; Xing, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Xing, G.; Zhao, F.; Zhao, Y.; et al. In situ observation of C60(C(COOH)2)2 interacting with living cells using fluorescence microscopy. Chin. Sci. Bull 2006, 51, 1060–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Liu, P.; Li, Z.; Qi, W.; Lu, Y.; Wu, W. Th(IV) Adsorption onto Oxidized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in the Presence of Hydroxylated Fullerene and Carboxylated Fullerene. Materials 2013, 6, 4168-4185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma6094168

Wang J, Liu P, Li Z, Qi W, Lu Y, Wu W. Th(IV) Adsorption onto Oxidized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in the Presence of Hydroxylated Fullerene and Carboxylated Fullerene. Materials. 2013; 6(9):4168-4185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma6094168

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jing, Peng Liu, Zhan Li, Wei Qi, Yan Lu, and Wangsuo Wu. 2013. "Th(IV) Adsorption onto Oxidized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes in the Presence of Hydroxylated Fullerene and Carboxylated Fullerene" Materials 6, no. 9: 4168-4185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma6094168