Ultrathin Six-Band Polarization-Insensitive Perfect Metamaterial Absorber Based on a Cross-Cave Patch Resonator for Terahertz Waves

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Structure Design and Simulation

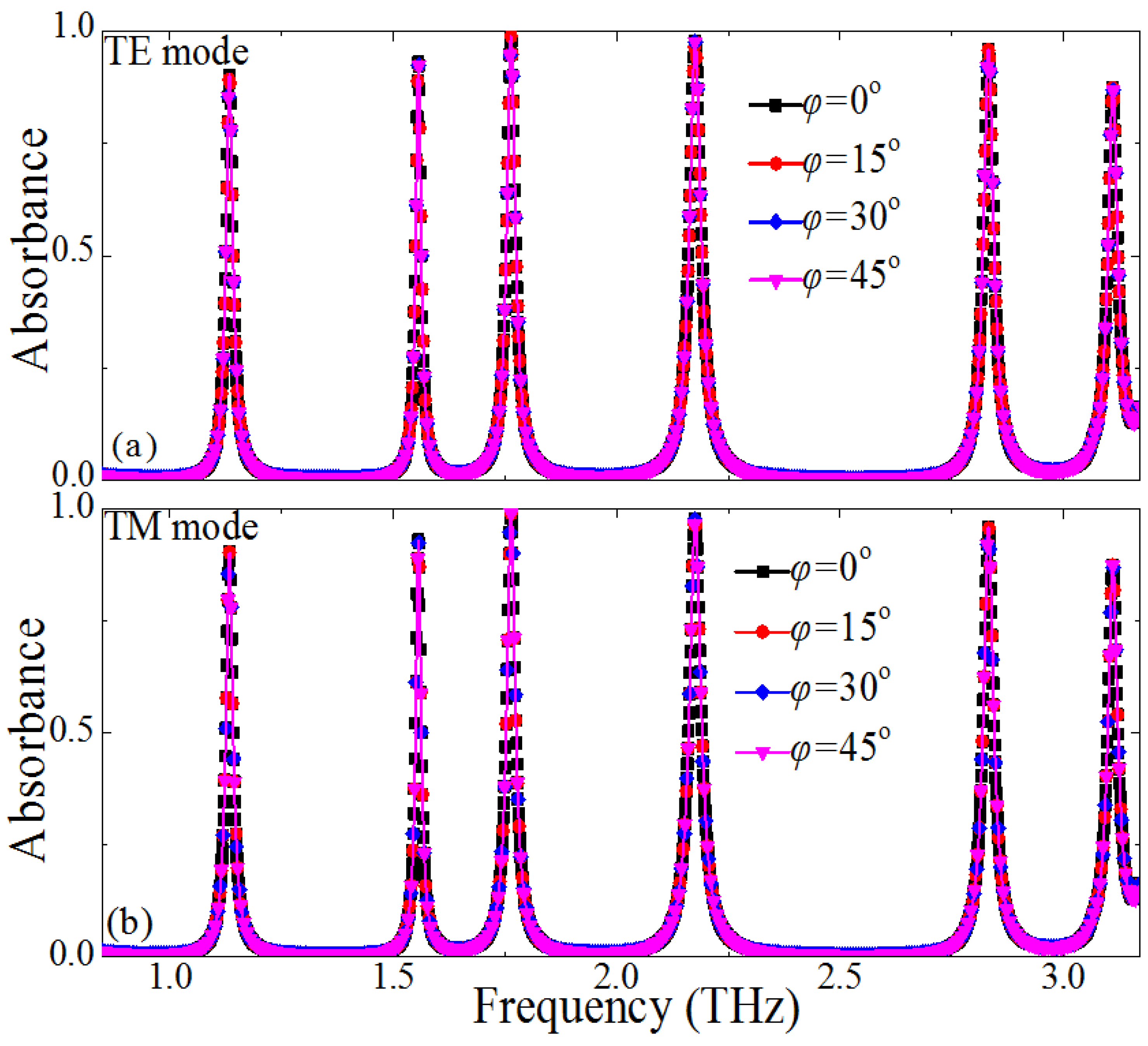

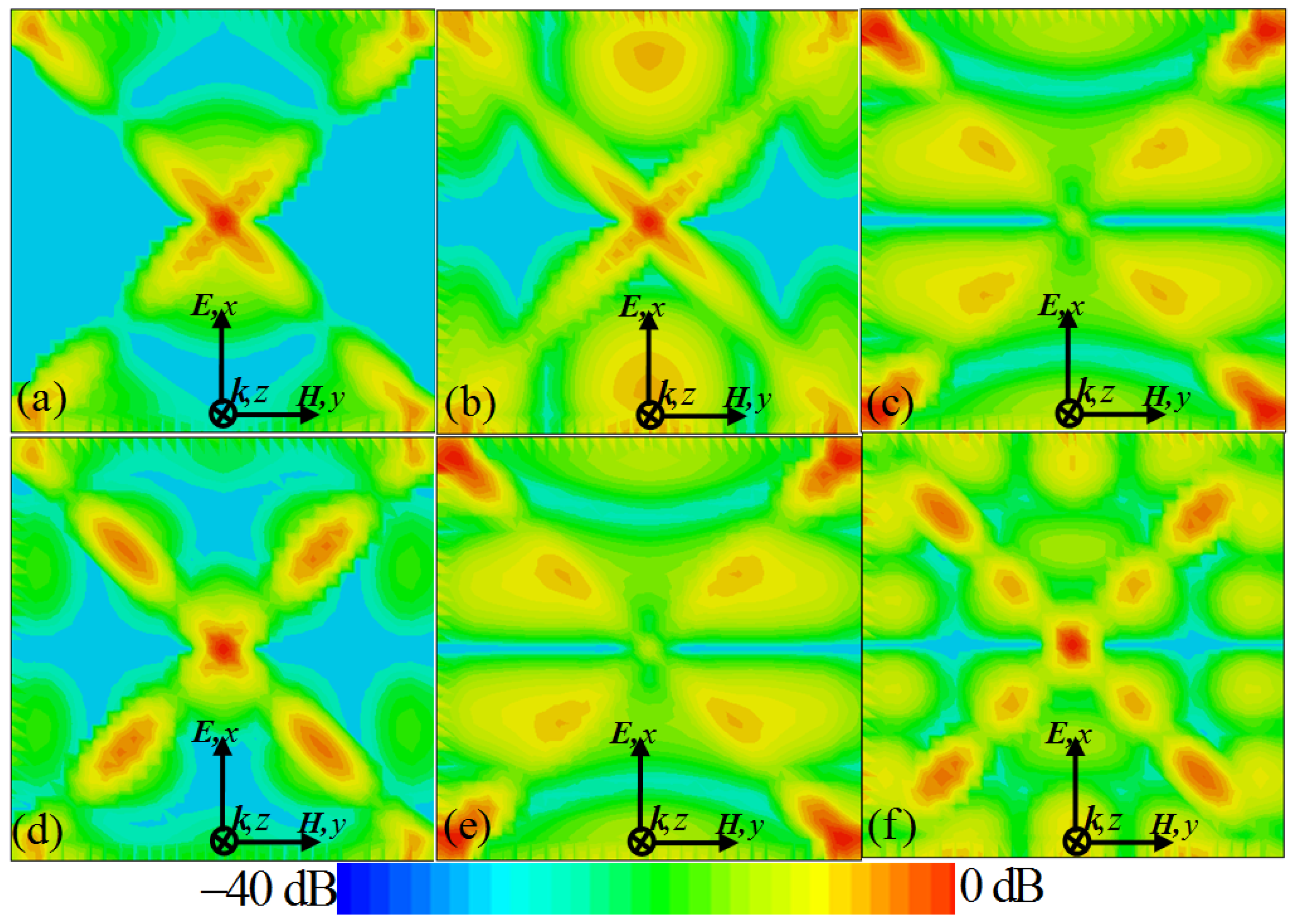

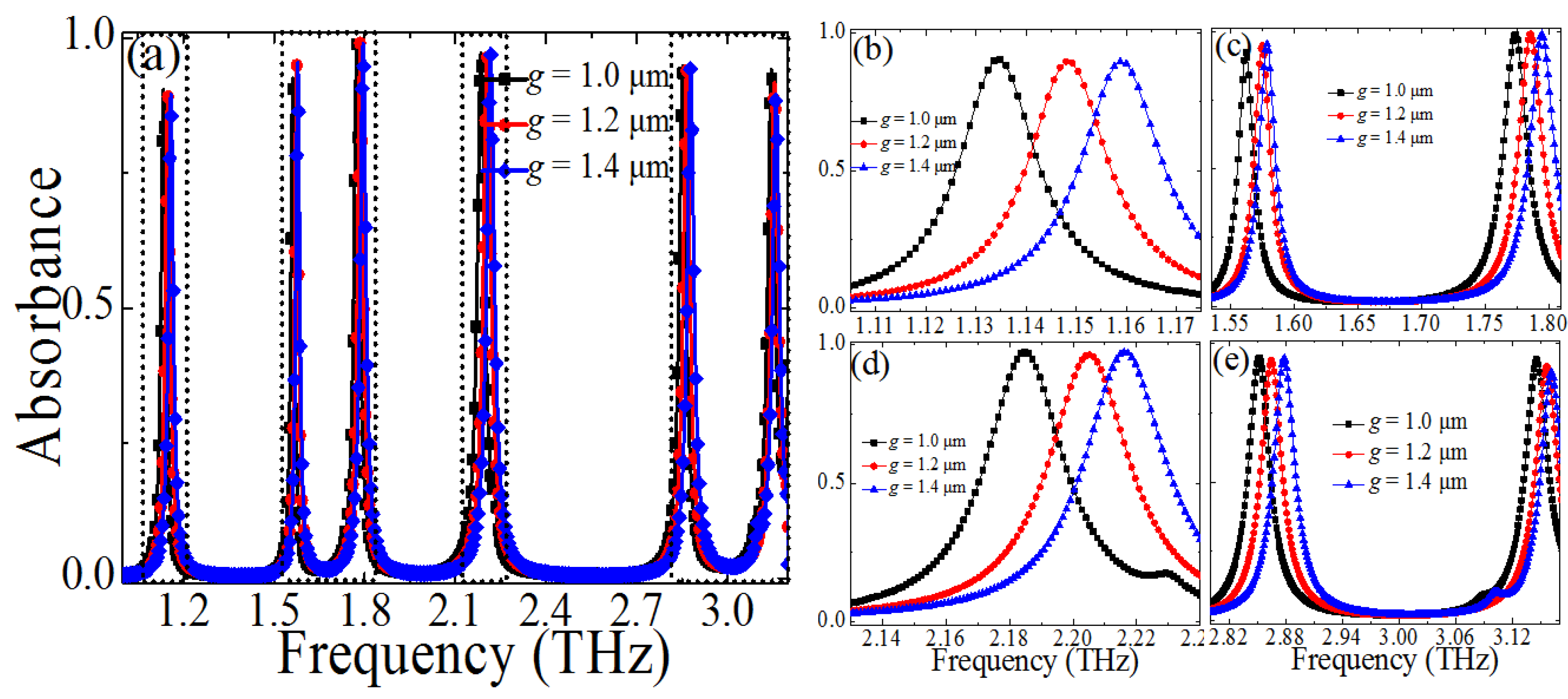

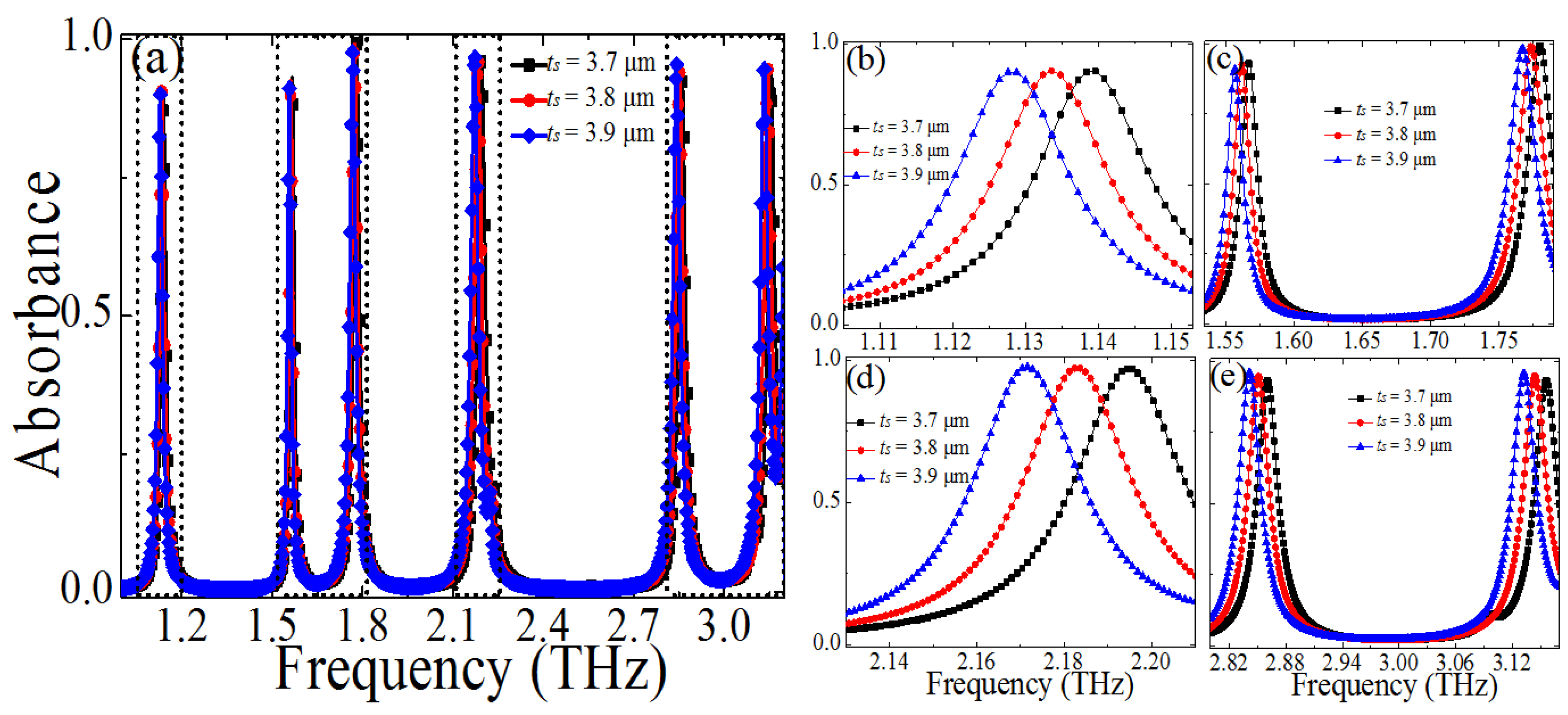

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Landy, N.I.; Sajuyigbe, S.; Mock, J.J.; Smith, D.R.; Padilla, W.J. Perfect metamaterial absorber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 207402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Yang, H.L.; Cheng, Z.Z.; Wu, N. Perfect metamaterial absorber based on a split-ring-cross resonator. Appl. Phys. A 2011, 102, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.W.; Liu, S.L.; Bian, B.R.; Wang, B.Y.; Ma, B.; Chen, L.; Xu, J. Multi-Band polarization insensitive metamaterial absorber based on chinese ancient coin-shaped structures. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 115, 204505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.Y.; Hua, W.Z.; Xie, Y.S.; Hu, Y.Q.; Li, L.Y. Dual band terahertz metamaterial absorber: Design, fabrication, and characterization. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 241111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.Q.; Jin, Y.; He, S. Omnidirectional, polarization-insensitive and broadband thin absorber in the terahertz regime. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2010, 27, 498–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, Q.; Grant, J.; Saha, S.C.; Khalid, A.; Cumming, D.R.S. A terahertz polarization insensitive dual band metamaterial absorber. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 945–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Nie, Y.; Gong, R.Z. A polarization-insensitive and omnidirectional broadband terahertz metamaterial absorber based on coplanar multi-squares films. Opt. Laser Technol. 2013, 48, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X.; Zhai, X.; Wang, G.Z.; Huang, W.Q.; Wang, L.L. Design of a four-band and polarization insensitive terahertz metamaterial absorber. IEEE Photonics J. 2015, 115, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zang, X.F.; Zhu, Y.M.; Shi, C.; Chen, L.; Cai, B.; Zhuang, S. Ultra-broadband terahertz perfect absorber by exciting multi-order diffractions in a double-layered grating structure. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 2032–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Withayachumnankul, W.; Upadhyay, A.; Headland, D.; Nie, Y.; Gong, R.Z.; Bhaskaran, M.; Sriram, S.; Abbott, D. Ultrabroadband plasmonic absorber for terahertz waves. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2015, 3, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhu, Q.F. Design of six-band terahertz perfect absorber using a simple U-shaped closed-ring resonator. IEEE Photonics J. 2016, 8, 5500608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Starr, T.; Starr, A.F.; Padilla, W.J. Infrared spatial and frequency selective metamaterial with near-unity absorbance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 207403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Cheng, H.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Duan, X.; Gu, C.; Tian, J. Polarization insensitive and omnidirectional broadband near perfect planar metamaterial absorber in the near infrared regime. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 253104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Wen, Y.Z.; Yu, X.M. Broadband metamaterial absorber at mid-infrared using multiplexed cross resonators. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 30724–30730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, D.; Tao, K.Y.; Wang, Q. Ultrabroadband mid-infrared light absorption based on a multi-cavity plasmonic metamaterial array. Plasmonics 2016, 11, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Mao, X.S.; Wu, C.J.; Wu, L.; Gong, R.Z. Infrared non-planar plasmonic perfect absorber for enhanced sensitive refractive index sensing. Opt. Mater. 2016, 53, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, T.; Paudel, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Kempa, K. Metamaterial plasmonic absorber structure for high efficiency amorphous silicon solar cells. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.Y.; Chen, S.Q.; Liu, W.W.; Cheng, H.; Li, Z.C.; Tian, J.G. Polarization-insensitive and wide-angle broadband nearly perfect absorber by tunable planar metamaterials in the visible regime. J. Opt. 2014, 16, 125107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Wei, C.; Simpson, R.E.; Zhang, L.; Cryam, M.J. Broadband polarization-independent perfect absorber using a phase-change metamaterial at visible frequencies. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, J.W.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Yun, B.F.; Lv, L.; Yao, H.B.; Fu, Y.H.; Ren, N.F. Broadband visible-light absorber via hybridization of propagating surface plasmon. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 1965–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.Q.; Tan, S.Y.; Yahiaoui, R.; Yan, F.P.; Zhang, W.L.; Singh, R. Experimental demonstration of ultrasensitive sensing with terahertz metamaterial absorbers: A comparison with the metasurfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 031107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, K.; Ku, Z.; Silva, S.; Jeon, J.; Kim, J.O.; Lee, S.J.; Urbas, A.; Zhou, J.F. A Large-Area, mushroom-capped plasmonic perfect absorber: Refractive index sensing and fabry–perot cavity mechanism. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2015, 3, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayal, G.; Chin, X.Y.; Soci, C.; Singh, R. High-Q plasmonic fano resonance for multiband surface-enhanced infrared absorption of molecular vibrational sensing. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, K.; Ferry, V.E.; Briggs, R.M.; Atwater, H.A. Broadband polarization-independent resonant light absorption using ultrathin plasmonic super absorbers. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greffet, J.J.; Carminati, R.; Joulain, K.; Mulet, J.P.; Mainguy, S.; Chen, Y. Coherent emission of light by thermal sources. Nature 2002, 416, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.F.; Chen, H.T.; Koschny, T.; Azad, A.K.; Taylor, A.J.; Soukoulis, C.M.; O’Hara, J.F. Application of metasurface description for multilayered metamaterials and an alternative theory for metamaterial perfect absorber. arXiv, 2011; arXiv:1111.0343. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.Y.; Wang, J.; Du, H.L.; Wang, J.F.; Qu, S.B. Achieving a multiband metamaterial perfect absorber via a hexagonal ring dielectric resonator. Chin. Phys. B 2015, 24, 064201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Gao, J.; Cao, X.Y.; Zheng, G. Polarization-insensitive and thin stereometamaterial with broadband angular absorption for the oblique incidence. Appl. Phys. A 2015, 119, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomanis, B.M.; Watts, C.M.; Koirala, M.; Liu, X.L.; Tyler, T.; West, K.G.; Starr, T.; Bringuier, J.N.; Starr, A.F.; Jokerst, N.M.; et al. Bilayer metamaterials as fully functional near-perfect infrared absorbers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 021107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F.; Cui, Y.; Ge, X.; Zhang, F.; Jin, Y.; He, S. Ultra-broadband microwave metamaterial absorber. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 103506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Nie, Y.; Gong, R.Z. Metamaterial absorber and extending absorbance bandwidth based on multi-cross resonators. Appl. Phys. B 2013, 111, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollatou, T.M.; Dimitriadis, A.I.; Assimonis, S.D.; Kantartzis, N.V.; Antonopoulosm, S.C. Multi-band, highly absorbing, microwave metamaterial structures. Appl. Phys. A 2014, 115, 555–561. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Fuang, K.H.; Xu, J.; Ma, H.; Jin, Y.; He, S.; Fang, N.X. Ultrabroadband light absorption by a sawtooh anisotropic metamaterial slab. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayal, G.; Ramakrishna, S.A. Multipolar localized resonances for multi-band metamaterial perfect absorbers. J. Opt. 2014, 16, 094016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dung, N.V.; Tuong, P.V.; Yoo, Y.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Tung, B.S.; Lam, V.D.; Rhee, J.Y.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Chen, L.Y.; et al. Perfect and broad absorption by the active control of electric resonance in metamaterial. J. Opt. 2015, 17, 045105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.X. Single-Patterned Metamaterial Structure Enabling Multi-band Perfect Absorption. Plasmonics 2017, 12, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kota, I.; Toshiyoshi, H.; Iizuka, H. Metal-insulator-metal metamaterial absorbers consisting of proximity-coupled resonators with the control of the fundamental and the second-order frequencies. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 119, 063101. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, X.; Cui, T.J. Photoexcited broadband redshift switch and strength modulation of terahertz metamaterial absorber. J. Opt. 2012, 14, 114012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Gong, R.Z.; Cheng, Z.Z. A photoexcited broadband switchable metamaterial absorber with polarization-insensitive and wide-angle absorption for terahertz waves. Opt. Commun. 2016, 361, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Srivastava, Y.K.; Manjappa, M.; Singh, R. Sensing with toroidal metamaterial. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 121108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landy, N.I.; Bingham, C.M.; Tyler, T.; Jokerst, N.; Smith, D.R.; Padilla, W.J. Design, theory, and measurement of a polarization-insensitive absorber for terahertz imaging. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 125104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Xiao, T.; Yang, H.L.; Xiao, B.X. Study on the simulation and measurement of ring structures metamaterial absorber. Acta Phys. Sin. 2010, 59, 5715–5719. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Kaiser, S.; Giessen, H. Magnetoinductive and electroinductive coupling in plasmonic metamaterial molecules. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20, 4521–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, O.P.; Zabala, N.; Borisov, A.G.; Halas, N.J.; Nordlander, P.; Aizpurua, J. Optical spectroscopy of conductive junctions in plasmonic cavities. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dung, N.V.; Tung, B.S.; Khuyen, B.X.; Yoo, Y.J.; Tuong, P.V.; Lee, Y.P.; Rhee, J.Y.; Lam, V.D.; Kim, K.W. Metamaterial perfect absorber using the magnetic resonance of dielectric inclusions. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2016, 6, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Pham, V.T.; Rhee, J.Y.; Kim, K.W.; Jang, W.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Cheong, H.; Lee, Y.P. Polarization-independent dual-band perfect absorber utilizing multiple magnetic resonances. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 32484–32490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.T. Interference theory of metamaterial perfect absorbers. Opt. Express 2012, 7, 7165–7175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanghuang, T.L.; Chen, W.J.; Huang, Y.J.; Wen, G.J. Analysis of metamaterial absorber in normal and oblique incidence by using interference theory. AIP Adv. 2013, 3, 102118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.X.; Sandhu, S.; Otey, C.; Fan, S.H.; Sinclair, M.B.; Luk, T.S. Temporal coupled mode theory for thermal emission from a single thermal emitter supporting either a single mode or an orthogonal set of modes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 103104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, L.; Yang, L.; Nadzeyka, A.; Bauerdick, S.; He, S.L. Enhanced broadband absorption in gold by plasmonic tapered coaxial holes. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 32233–32244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsushi, S.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, Z.M. Resonant frequency and bandwidth of metamaterial emitters and absorbers predicted by an RLC circuit model. J. Quantit. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2014, 149, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, R.; Qiu, J.; Liu, L.H.; Ding, W.Q.; Chen, L.X. Parallel LC circuit model for multi-band absorption and preliminary design of radiative cooling. Opt. Express 2014, 22, A1713–A1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nath, J.; Modak, S.; Rezadad, I.; Panjwani, D.; Rezaie, F.; Cleary, J.W.; Peale, R.E. Far-infrared absorber based on standing-wave resonances in metal-dielectric-metal cavity. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 20366–20380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.; Bhattarai, K.; Kim, D.-K.; Kim, J.O.; Urbas, A.; Lee, S.J.; Ku, Z.; Zhou, J.F. A low-loss metasurface antireflection coating on dispersive surface plasmon structure. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manjappa, M.; Srivastava, Y.K.; Cong, L.Q.; Al-Naib, I.; Singh, R. Active photoswitching of sharp Fano resonances in THz metadevices. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1603355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.S.; Bhattarai, K.; Kim, D.K.; Kang, S.W.; Kim, J.O.; Zhou, J.F.; Jang, W.Y.; Noyola, M.; Urbas, A.; Ku, Z.; et al. Enhanced transmission due to antireflection coating layer at surface plasmon resonance wavelengths. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 30161–30169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z.; Luo, Y.; Fernández-Domínguez, A.I.; Shen, X.P.; Maier, S.A.; Cui, T.J. High-order localized spoof surface plasmon resonances and experimental verifications. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.F.; Economon, E.N.; Koschny, T.; Soukoulis, C.M. Unifying approach to left-handed material design. Opt. Lett. 2006, 31, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.Q.; Pitchappa, P.; Wu, Y.; Ke, L.; Lee, C.K.; Singh, N.; Yang, H.; Singh, R. Active multifunctional microelectromechanical system metadevices: Applications in polarization control, wavefront deflection, and holograms. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2017, 5, 1600716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.Z.; Withayachumnankul, W.; Upadhyay, A.; Headland, D.; Nie, Y.; Gong, R.Z.; Bhaskaran, M.; Sriram, S.; Abbott, D. Ultrabroadband reflective polarization convertor for terahertz waves. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 181111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, Y.Z.; Huang, M.L.; Chen, H.R.; Guo, Z.Z.; Mao, X.S.; Gong, R.Z. Ultrathin Six-Band Polarization-Insensitive Perfect Metamaterial Absorber Based on a Cross-Cave Patch Resonator for Terahertz Waves. Materials 2017, 10, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10060591

Cheng YZ, Huang ML, Chen HR, Guo ZZ, Mao XS, Gong RZ. Ultrathin Six-Band Polarization-Insensitive Perfect Metamaterial Absorber Based on a Cross-Cave Patch Resonator for Terahertz Waves. Materials. 2017; 10(6):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10060591

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Yong Zhi, Mu Lin Huang, Hao Ran Chen, Zhen Zhong Guo, Xue Song Mao, and Rong Zhou Gong. 2017. "Ultrathin Six-Band Polarization-Insensitive Perfect Metamaterial Absorber Based on a Cross-Cave Patch Resonator for Terahertz Waves" Materials 10, no. 6: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10060591