An Easy-Made, Economical and Efficient Carbon-Doped Amorphous TiO2 Photocatalyst Obtained by Microwave Assisted Synthesis for the Degradation of Rhodamine B

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

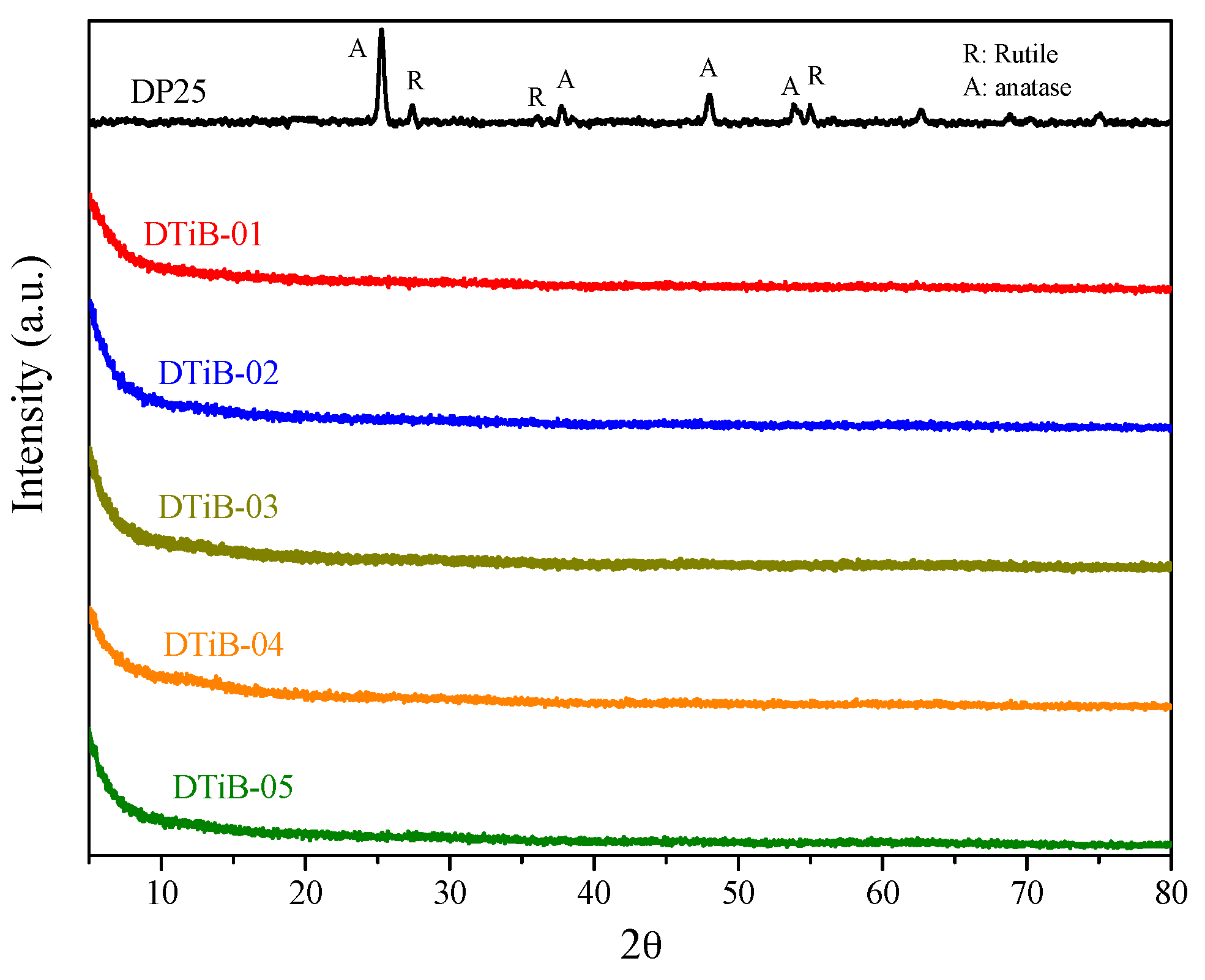

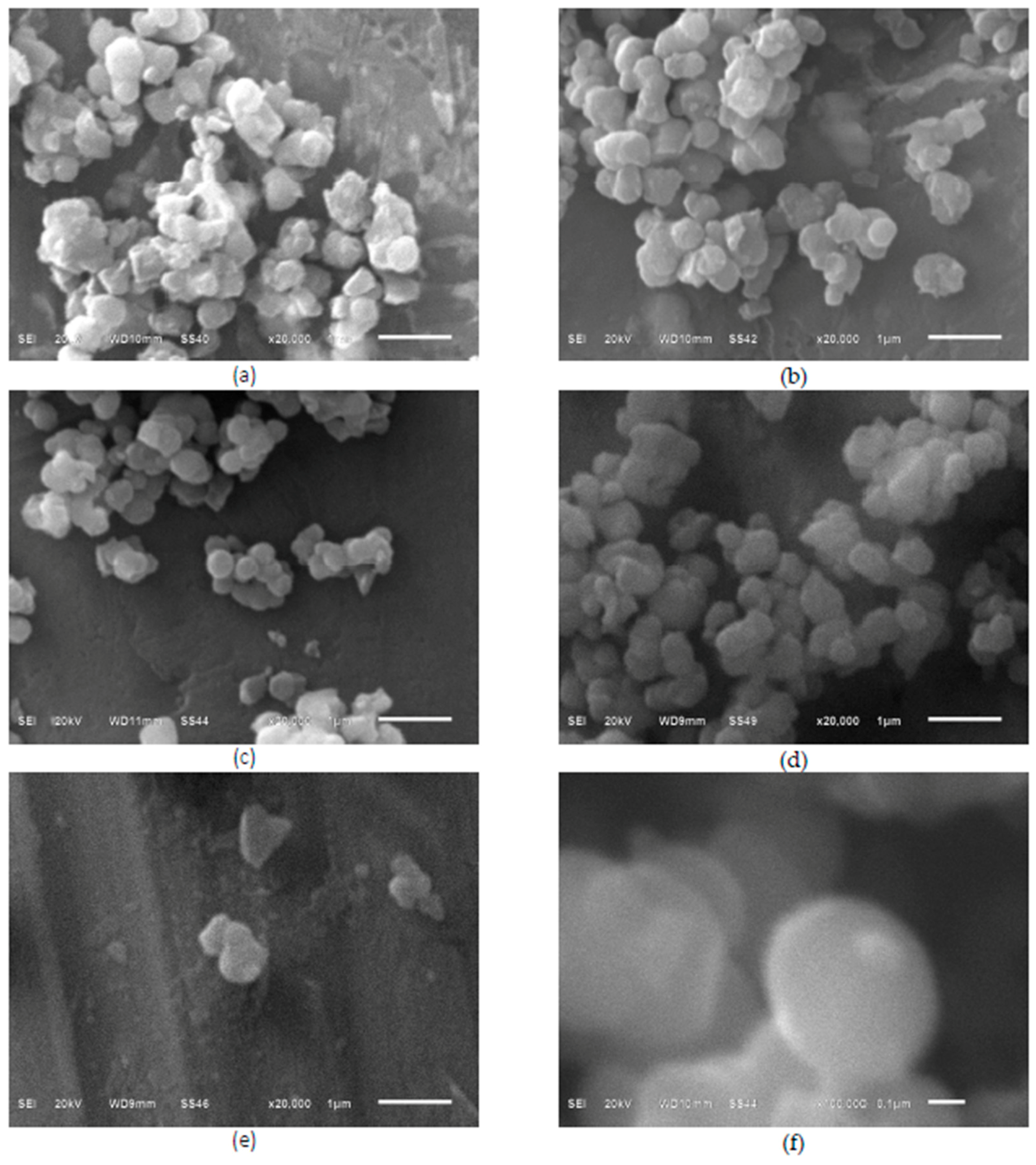

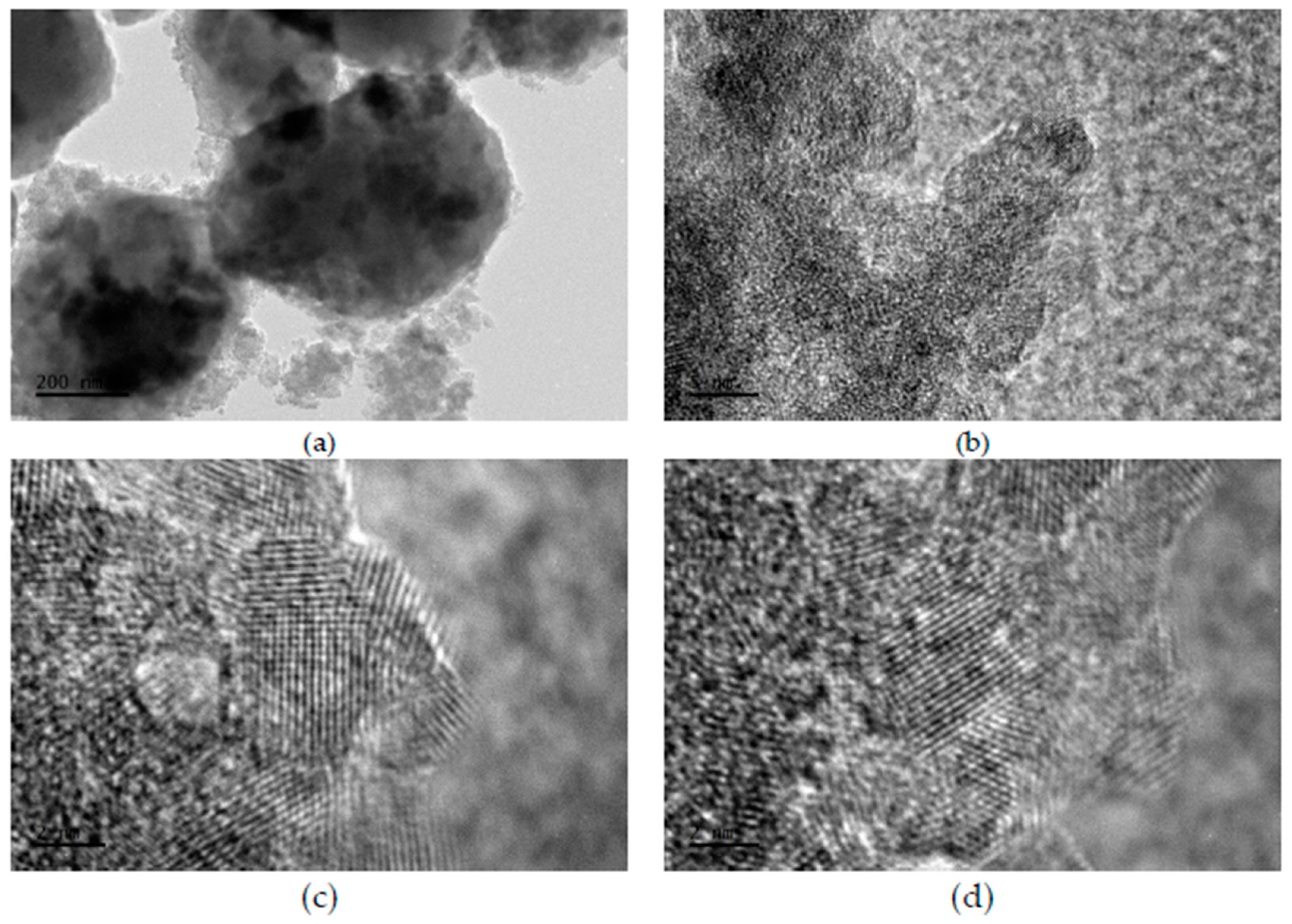

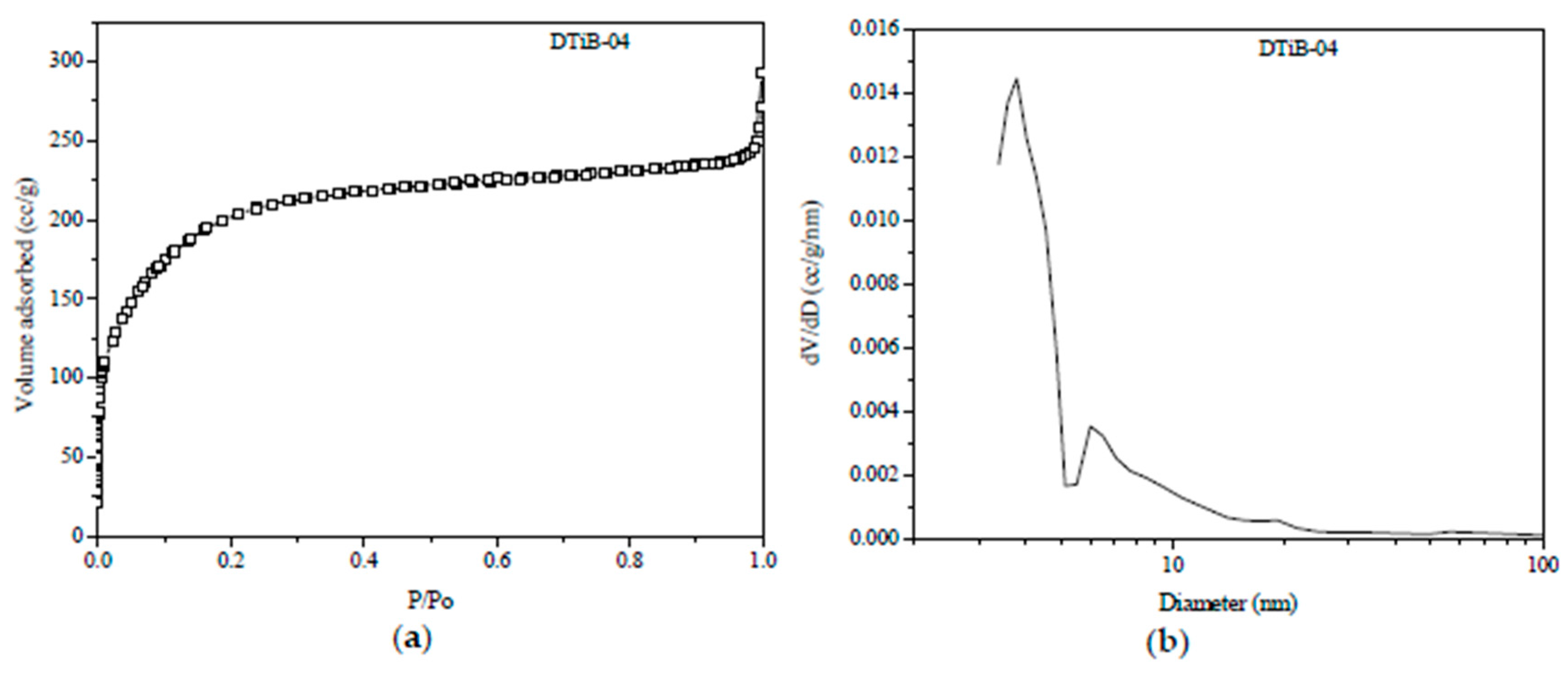

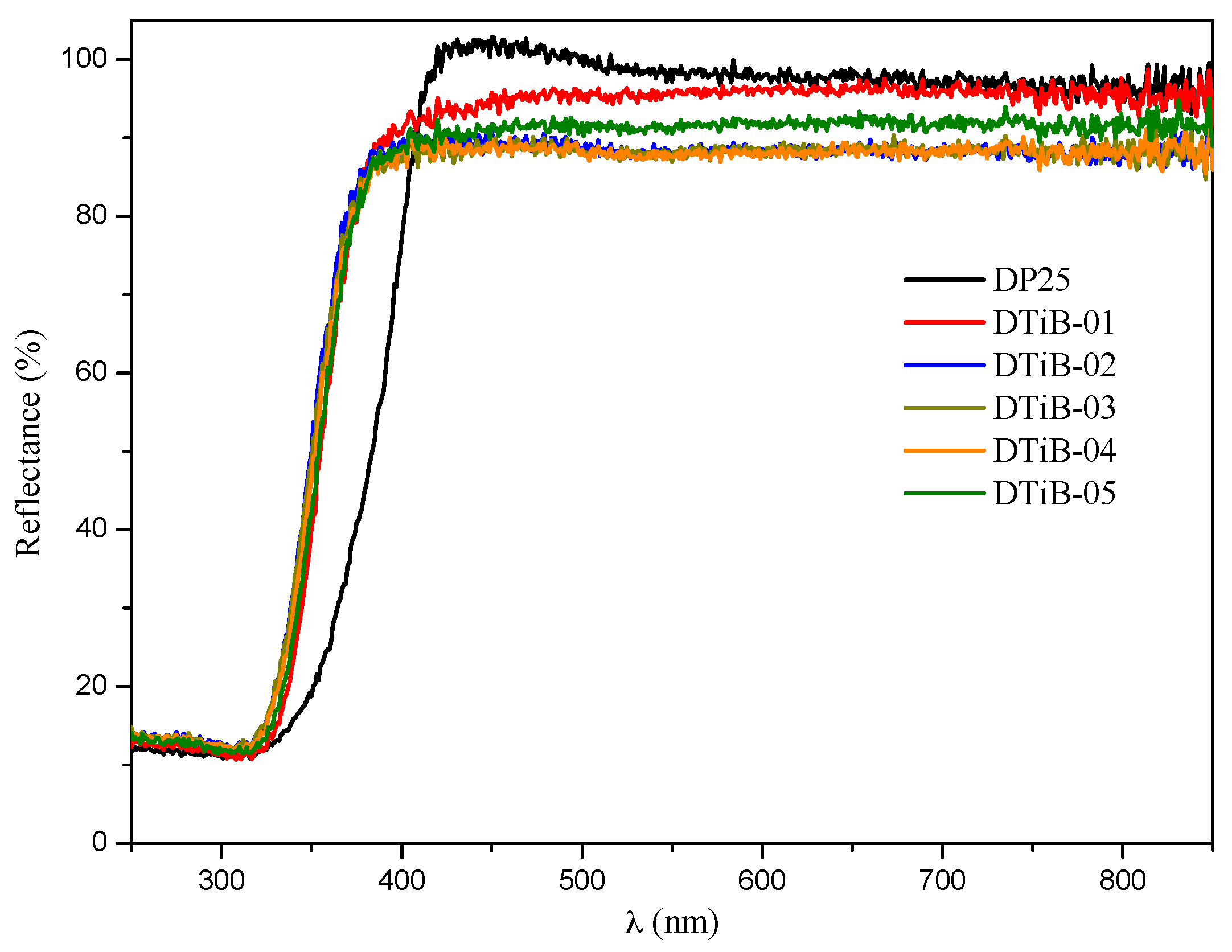

2.1. Morphology, Short-Range Crystalline Structure and Surface Characterization

2.2. FT-IR Analysis

2.3. Thermogravimetric (TG) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analyses

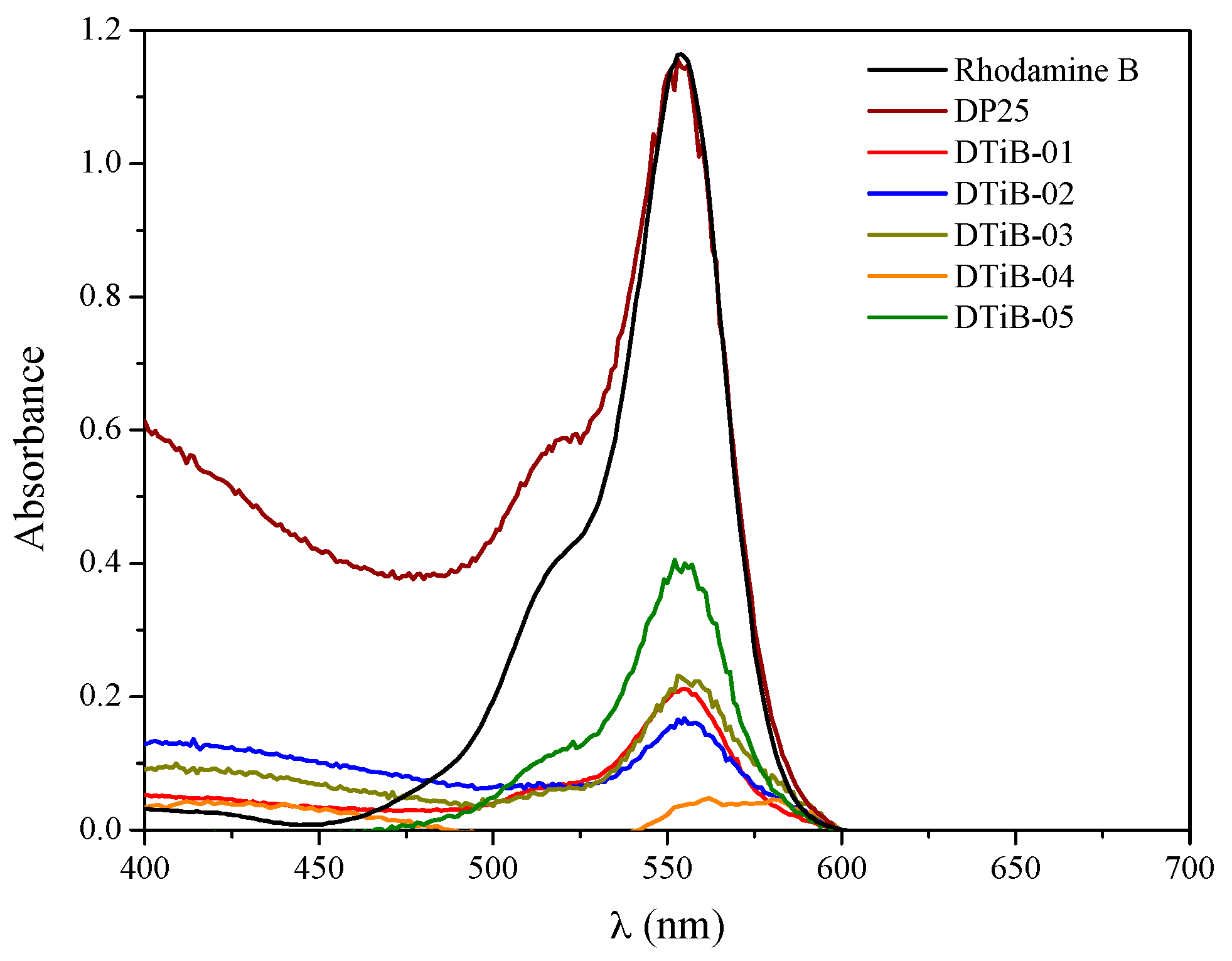

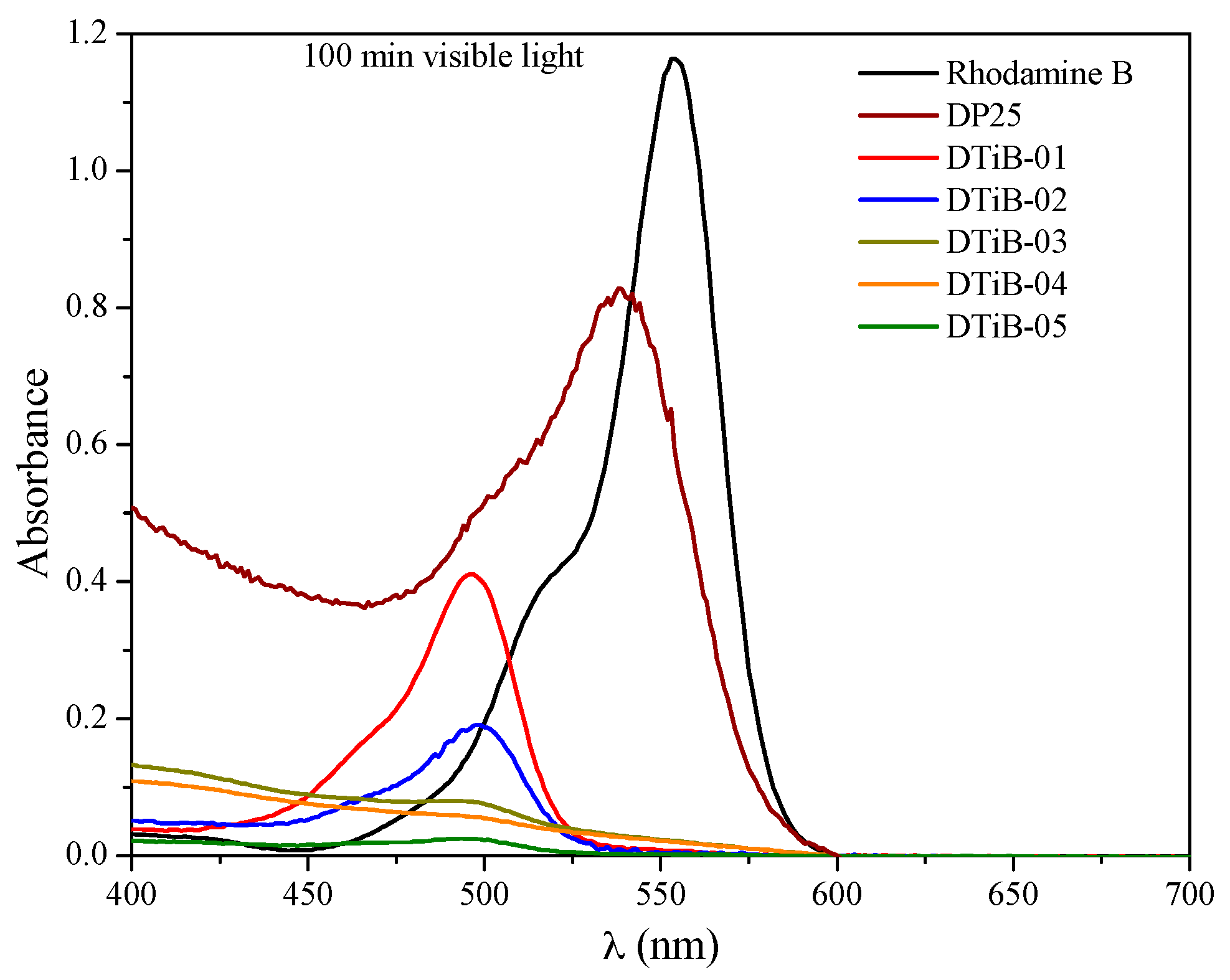

2.4. Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B Using the TiO2 Products

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and Reagents

3.2. Synthesis of Carbon-Doped Amorphous Titanium Dioxide (CD-aTiO2)

3.3. Characterization and Analytical Techniques

3.4. Measurements of Photocatalytic Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramos-Delgado, N.A.; Gracia-Pinilla, M.A.; Mangalaraja, R.V.; O’Shea, K.; Dionysiou, D.D. Industrial synthesis and characterization of nanophotocatalysts materials: Titania. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2016, 5, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.; Cheng, B.; Yu, J. Surface modification and enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of TiO2: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 392, 658–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xiong, Y. Steering charge kinetics in photocatalysis: Intersection of materials syntheses, characterization techniques and theoretical simulations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2893–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Han, H.; Li, C. Titanium Dioxide-Based Nanomaterials for Photocatalytic Fuel Generations. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9987–10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landmann, M.; Rauls, E.; Schmidt, W.G. The electronic structure and optical response of rutile, anatase and brookite TiO2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2012, 24, 195503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landmann, M.; Kohler, T.; Koppen, S.; Rauls, E.; Frauenheim, T.; Schmidt, W.G. Fingerprints of order and disorder in the electronic and optical properties of crystalline and amorphous TiO2. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 064201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanna, M.; Wongnawa, S.; Buddee, S.; Dilokkhunakul, K.; Pinpithak, P. Amorphous titanium dioxide: A recyclable dye remover for water treatment. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2010, 53, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Shaner, M.R.; Beardslee, J.A.; Lichterman, M.; Brunschwig, B.S.; Lewis, N.S. Amorphous TiO2 coatings stabilize for Si, GaAs, and GaP photoanodes for efficient water oxidation. Science 2014, 344, 1005–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.H.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, K.W.; Han, S.D.; Singh, I. Synthesis of Amorphous Er3+-Yb3+ Co-doped TiO2 and Its Application as a Scattering Layer for Dye-sensitized Solar Cells. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2009, 30, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddee, S.; Wongnawa, S.; Sirimahachai, U.; Puetpaibool, W. Recyclable UV and visible light photocatalytically active amorphous TiO2 doped with M (III) ions (M = Cr and Fe). Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 126, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.H.; Wang, L.W. Electronic structures and current conductivities of B, C, N and F defects in amorphous titanium dioxide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 11908–11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghuman, K.K.; Singh, C.V. Effect of doping on electronic structure and photocatalytic behavior of amorphous TiO2. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2013, 25, 475501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.; Matsuoka, M.; Takeuchi, M.; Zhang, J.; Horiuchi, Y.; Anpo, M.; Bahnemann, D.W. Understanding TiO2 Photocatalysis: Mechanisms and Materials. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9919–9986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Ho, W.; Lee, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, G.; Yu, J.C. Effect of Carbon Doping on the Mesoporous Structure of Nanocrystalline Titanium Dioxide and Its Solar-Light-Driven Photocatalytic Degradation of NOx. Langmuir 2008, 24, 3510–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, D.; Xing, M.; Zhang, J. Hydrophobic Carbon-Doped TiO2/MCF-F Composite as a High Performance Photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 7329–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, M.; Kojin, F.; Tryba, B.; Toyoda, M. Carbon-coated anatase: The role of the carbon layer for photocatalytic performance. Carbon 2005, 43, 1652–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, D.H.; Moon, J.H. Carbon-Deposited TiO2 3D Inverse Opal Photocatalysts: Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity and Enhanced Activity in a Viscous Solution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 12526–12532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, I.; Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; An, Q. Carbon wrapped and doped TiO2 mesoporous nanostructure with efficient visible-light photocatalysist for NO removal. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 391, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Cao, C.; Chen, S.; He, M.; Fang, J.; Chen, J.; Li, X.F.; Li, D.Z. Investigation of nitrogen doped and carbon species decorated TiO2 with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity by using chitosan. Appl. Catal. B. 2015, 179, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Kim, W.; Park, H.; Tachikawa, T.; Majima, T.; Choi, W. Carbon-doped TiO2 photocatalyst synthesized without using an external carbon precursor and the visible light activity. Appl. Catal. B. 2009, 91, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkanen, J.-P.; Kanerva, T.; Mäntylä, T. The effect of acidity in low-temperature synthesis of titanium dioxide. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 304, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, P.; Tian, J.; Zhao, Z.; Shi, W.; Gao, S.; Cui, F. Amorphous TiO2 doped with carbon for visible light photodegradation of rhodamine B and 4-chlorophenol. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 324, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Sugimoto, T. Formation Mechanism of Amorphous TiO2 Spheres in Organic Solvents 3. Effects of Water, Temperature, and Solvent Composition. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 18445–18454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.M.; Al-Thani, N.J.; Tawbi, K.; Al-Kandari, H. Carbon/nitrogen-doped TiO2: New synthesis route, characterization and application for phenol degradation. Arabian J. Chem. 2016, 9, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.A.; Fernandez-Cervantes, I.; Agustin-Serrano, R.; Anzo, A.; Sampedro, M.P. Patterns formation in ferrofluids and solid dissolutions using stochastic models with dissipative dynamics. Eur. Phys. J. B 2016, 89, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maletic, M.; Vukcevic, M.; Kalijadis, A.; Jankovic-Castvan, I.; Dapcevic, A.; Lausevic, Z.; Laušević, M. Hydrothermal synthesis of TiO2/carbon composites and their application for removal of organic pollutants. Arabian J. Chem. 2016, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W.; Everett, D.H.; Haul, R.A.W.; Moscou, L.; Pierotti, R.A.; Rouquerol, J.; Siemieniewska, T. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity (Recommendations 1984). Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Factorovich, M.; Guz, L.; Candal, R. N-TiO2: Chemical Synthesis and Photocatalysis. Adv. Phys. Chem. 2011, 2011, 821204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etacheri, V.; Michlits, G.; Seery, M.K.; Hinder, S.J.; Pillai, S.C. A Highly Efficient TiO2−xCx Nano-heterojunction Photocatalyst for Visible Light Induced Antibacterial Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 1663–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanivelu, K.; Im, J.S.; Lee, Y.S. Carbon Doping of TiO2 for Visible Ligtht Photo Catalysis—A Review. Carbon Sci. 2007, 8, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, C.S.; Schoonman, J.; van de Krol, R. Addition of carbon to anatase TiO2 by n-hexane treatment—Surface or bulk doping? Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 6342–6347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebraheem, S.; El-Saied, A. Band Gap Determination from Diffuse Reflectance Measurements of Irradiated Lead Borate Glass System Doped with TiO2 by Using Diffuse Reflectance Technique. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2013, 4, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochkind, M.; Pasternak, S.; Paz, Y. Using Dyes for Evaluating Photocatalytic Properties: A Critical Review. Molecules 2015, 20, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Liu, G.; Zhao, J.; Hidaka, H.; Serpone, N. Photoassisted Degradation of Dye Pollutants. V. Self-Photosensitized Oxidative Transformation of Rhodamine B under Visible Light Irradiation in Aquos TiO2 Dispertions. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 5845–5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Zou, J.-J.; Liu, X.-Y.; Liu, X.-J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L. Visible-Light-Induced Photodegradation of Rhodamine B over Hierarchical TiO2: Effects of Storage Period and Water-Mediated Adsorption Switch. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 12782–12786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Flores, A.; Valenzuela, M.A.; Luna-López, J.A.; Hernández de la Luz, A.D.; Muñoz-Arenas, L.C.; Méndez-Hernández, M.; Sosa-Sánchez, J.L. Synergetic Enhancement of the Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 with Visible Light by Sensitization Using a Novel Push-Pull Zinc Phthalocyanine. Int. J. Photoenergy 2017, 2017, 1604753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TiO2 Photocatalyst | Microwave Heating (t, min) | Eg (eV) | Adsorption (%) | λmax (nm) in the UV-Vis Analysis | C (%w) | O (%w) | Ti (%w) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DP25 | 0 | 3.10 | 1.3 | 554 | - | - | - |

| DTiB-01 | 0 | 3.37 | 80 | 555 | 21.22 | 38.34 | 40.43 |

| DTiB-02 | 2 | 3.41 | 84 | 555 | 20.75 | 40.04 | 39.21 |

| DTiB-03 | 4 | 3.40 | 78 | 556 | 23.56 | 39.99 | 36.55 |

| DTiB-04 | 6 | 3.39 | 95 | 563 | 24.29 | 40.11 | 35.60 |

| DTiB-05 | 8 | 3.38 | 60 | 554 | 22.04 | 37.10 | 40.87 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luna-Flores, A.; Sosa-Sánchez, J.L.; Morales-Sánchez, M.A.; Agustín-Serrano, R.; Luna-López, J.A. An Easy-Made, Economical and Efficient Carbon-Doped Amorphous TiO2 Photocatalyst Obtained by Microwave Assisted Synthesis for the Degradation of Rhodamine B. Materials 2017, 10, 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10121447

Luna-Flores A, Sosa-Sánchez JL, Morales-Sánchez MA, Agustín-Serrano R, Luna-López JA. An Easy-Made, Economical and Efficient Carbon-Doped Amorphous TiO2 Photocatalyst Obtained by Microwave Assisted Synthesis for the Degradation of Rhodamine B. Materials. 2017; 10(12):1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10121447

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuna-Flores, Adan, José L. Sosa-Sánchez, Marco Antonio Morales-Sánchez, Ricardo Agustín-Serrano, and J. A. Luna-López. 2017. "An Easy-Made, Economical and Efficient Carbon-Doped Amorphous TiO2 Photocatalyst Obtained by Microwave Assisted Synthesis for the Degradation of Rhodamine B" Materials 10, no. 12: 1447. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10121447