1. Introduction

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) pandemic has caused far-reaching effects in resource-limited settings. The continent of Africa has been particularly hard hit. It is estimated that two-thirds of the 33 million people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide, reside in this region, with a rising majority in rural areas [

1]. Based on data from 2008, an estimated 71% of all new infections, and 72% of AIDS-related deaths, occurred in sub-Saharan Africa [

1]. In response to these dismal statistics, the international community has responded by raising awareness of the medical needs of this region. These scale-up efforts have been quite successful as millions of Africans are gaining access to life-saving antiretroviral therapies [

2,

3].

While much attention has focused on the medical aspects of HIV/AIDS, other issues beyond the medical sector have emerged. HIV/AIDS further constrains the already fragile relationship between livelihood and the environment, as thoroughly described by Niehof, Rugalema, and Gillespie [

4]. Rural livelihood depends on several factors, including, natural resources, technology, knowledge, health, and access to education; many of which have been influenced by the pandemic. For instance, HIV/AIDS has greatly altered the population dynamics of this region by reducing the agricultural workforce. To compensate, many farmers have adopted less labor-intensive, unsustainable land use practices in an attempt to increase crop yield and generate revenue, or have left crops unseeded as a result of the diminished availability of laborers [

5]. Such issues are especially problematic in rural communities where many inhabitants depend on the natural environment as a source of income and as a means of preserving traditional and cultural practices [

6].

The juxtaposition of these factors evokes the question: what is the environmental impact of HIV/AIDS on the rural communities of sub-Saharan Africa? This review discusses the attributes of rural life that influence HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, describes the fluctuations in population dynamics as a result of the pandemic, and characterizes the variations in the management and use of the local environment. It also highlights recommendations to lessen and reverse the effects of HIV/AIDS on the natural environment in this region.

2. Literature Assessment

Searches of the MEDLINE and GreenFILE databases were conducted to identify pertinent articles. The searches were restricted to articles published in peer-reviewed journals in the English language. The terms

“HIV”,

“Africa”,

“rural” and

“environment” were used alone and in combination to yield the maximum number of articles within each database. Of the 147 publications identified, 13 were included for meeting all of the following inclusion criteria: pertained to the environment, described original research findings, involved patients with HIV/AIDS, location in sub-Saharan Africa, and focused on issues pertaining to rural community life. Publications failing to meet the above criteria were excluded. The citations of relevant articles were also reviewed to yield an additional 18 articles. The articles are classified by focus area in

Table 1.

3. HIV/AIDS in Rural Sub-Saharan Africa

3.1. The Rural Dimension of HIV/AIDS

The various HIV/AIDS epidemics across sub-Saharan Africa are diverse in terms of rate of spread and characteristic variations from region to region [

34]. The prevalence of disease tends to be greater in urban areas as compared to rural areas, with the urban-rural ratio estimated at 1.7:1.0 [

35]. However, there are also unique factors to rural life that contribute to disease transmission. For example, HIV/AIDS clinics and other related services are not as prevalent in villages and surrounding vicinities as they are in densely-populated cities; thus, limiting the amount of care as well as disease and treatment-related knowledge that reaches rural dwellers [

36]. This disparity in equitable access to care between rural and urban areas is steadily gaining awareness, but requires more progress to meet the needs of these areas [

37]. Many of these communities already face escalating food costs and decreased labor wages due to political instability and economic strife, which has given rise to food insecurity and malnutrition [

5,

27,

38]. Concurrently, the pandemic diminishes the workforce, increases poverty rates, reduces agricultural productivity, and transforms the structure of many rural households [

9,

10,

19]. This complex interaction does not always yield negative results, it merely reinforces the importance of recognizing the diversity of impacts from this disease [

11,

30,

34].

3.2. Rural Migration

The migratory tendencies of infected individuals in these areas further complicate rural life for people with HIV/AIDS. Previous studies of migration patterns have noted that HIV-infected individuals often return to their home village in order to be closer to relatives that can provide and care for them while they are ill [

14,

15]. This process, in turn, may increase the risk of transmission to others in home villages. Migration patterns among travelling laborers also impacts the spread of HIV/AIDS in rural communities, particularly by young male workers. Researchers were able to describe a pattern in which workers would leave their rural homes in search of work in the city by modeling the movement of workers in rural South Africa [

16]. Once in the city, there was a tendency for workers to engage in high-risk sexual behavior, thus, increasing the risk for disease acquisition to others [

16]. Once infected, their return to their rural home increased the risk of transmission to their partners and to other members of their village [

16]. These multiple avenues for the spread and introduction of HIV/AIDS into the rural community may serve as areas for effective intervention.

4. Changes in Population Dynamics

4.1. Population Growth

One of the most notable consequences of the HIV/AIDS pandemic has been the reduction in population growth as a result of AIDS-related mortality. A report produced by the U.S. Census Bureau in 2004 indicated that many sub-Saharan African countries are projected to experience a decline in life expectancy [

39]. This report forecasted that by 2010, life expectancy would have dropped to nearly 30 years of age for some South African countries, levels that were last observed at the start of the 20th century [

39]. At greatest risk for this reversion are countries with a high prevalence of HIV/AIDS. For instance, Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland each have a HIV seroprevalence greater than 20% [

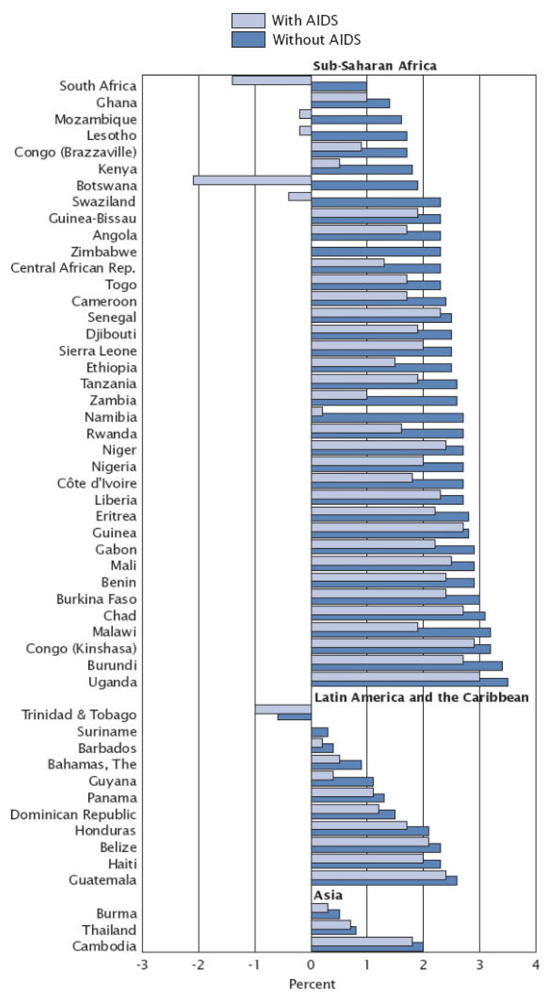

39]. Based on modeling, these countries were all expected to experience negative population growth attributable to AIDS by 2010; these projected growth rates (with and without AIDS) are illustrated in

Figure 1 [

39]. These dramatic changes in population growth impact rural livelihoods. Analyzing the effects of the growth and reduction of certain subgroups within the population at large reveals the array of complexities and challenges that arise from declines in population growth, as will be discussed in subsequent sections of this review.

4.2. The Age Dynamic

Increased mortality due to AIDS, will not only reduce the overall population, but will also distort the age structure of many of these countries [

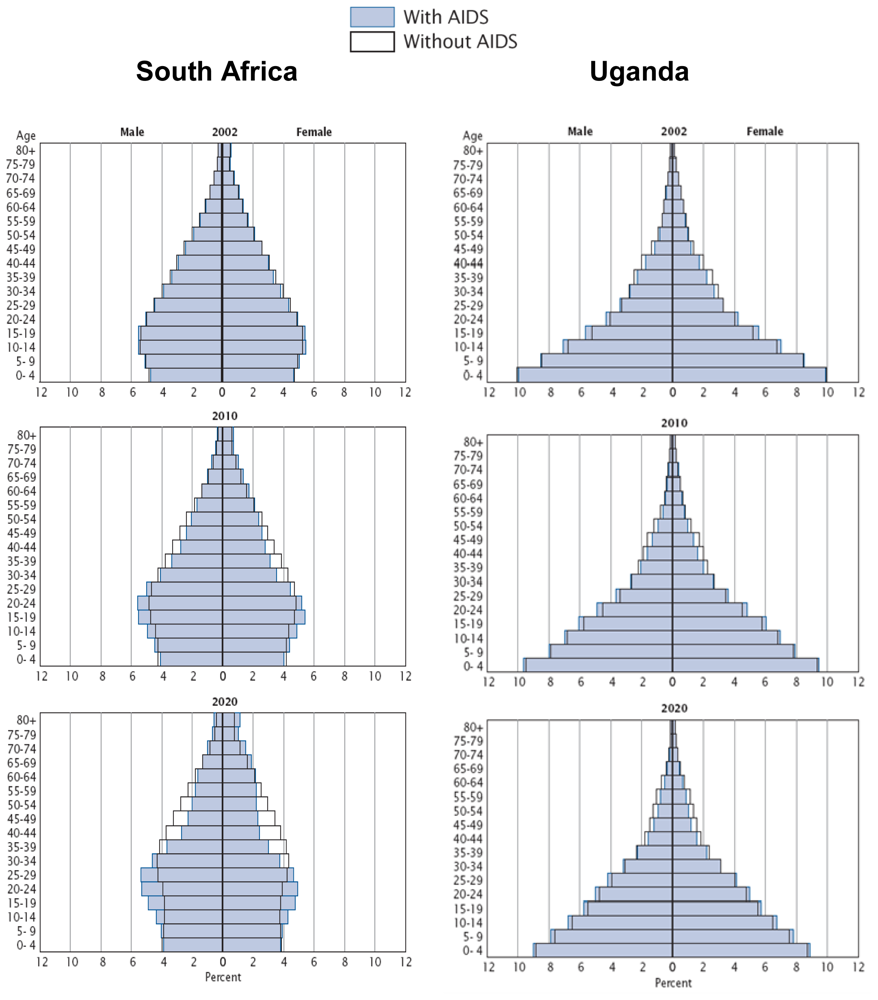

39]. Such demographic information is best depicted using a population pyramid. The population pyramid is a graphical representation of the different age groups for a given country and typically resembles a ‘pyramid’ shape; this shape denotes population growth. One way to discern the impact of AIDS-related mortality is to compare population pyramids for different countries with varying disease burden.

The deleterious impact of disease on population growth is a mounting challenge for countries with high seroprevalence. First, consider that the estimated seroprevalence in 2001 was 20% in South Africa and 5% in Uganda [

39]. Because of this, South Africa will progressively veer away from the traditional pyramid shape with a predominant loss of the younger and adult populations, indicative of negative population growth, as illustrated in

Figure 2. In contrast, very little changes in the population are expected to occur in Uganda.

The age distortion of the population influences the rural family unit. In South Africa, the percentage of the adult population is decreasing, yet the percentage of the elderly population is increasing. This is hypothesized to be a result of decreasing fertility rates among women, low levels of life expectancy among children born with HIV/AIDS, and adult AIDS mortality [

40]. Suppression of urban growth rates in South Africa, as well as other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, has disproportionately affected young and middle-aged adults; however, the impact of HIV/AIDS may become more widely distributed across age groups over time [

40].

Elders often resume primary responsibility for the household following the death of their adult children, as demonstrated by an interview of women sampled from South African villages by Schatz

et al. [

17]. The authors described that many of these older women have access to government pensions to support themselves; however, in the absence of their income-producing adult children, these funds are often insufficient for an entire household [

17]. Older females are left to cope with these monetary constraints and food insecurities while still caring for children and sick family members [

17]. As the family dynamic and economic outlets shift, these women have little time to adopt sustainable use of the available natural resources.

4.3. The Gender Dynamic

Approximately 60% of individuals living with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa are female [

1]. In contrast, females only accounted for 25% of all HIV/AIDS diagnoses among adults and adolescents in the United States in 2008 [

41]. Women are at higher risk of acquiring HIV through heterosexual transmission due to physiology; however, other social, cultural, legal, and economic factors may play a role in producing the disproportionately higher rates in women living in sub-Saharan Africa [

42]. Some African cultures allow for the subordination of females, whereby, women may lack economic independence, assets, and the ability to take charge of their sexual existence. Dunkle

et al. demonstrated that women with violent or controlling male partners were at increased risk for HIV infection [

20]. The effect of AIDS-related mortality on gender imbalance can also be seen in the two population pyramids in

Figure 2. By 2020, the population of South Africa is projected to experience a gender imbalance, wherein males aged 15–44 years will likely outnumber their female counterparts [

39]. These gender imbalances are aggravated by HIV/AIDS and continue to present a formidable challenge for females.

In addition to the numerous farming responsibilities, women must also face property inheritance issues. Female control of agricultural households typically transpires following the death of a male spouse, often from AIDS. This raises the concern of land tenure and ownership. Land in sub-Saharan Africa is traditionally inherited through a patriarchal lineage; thus, widowed women are vulnerable to losing land rights upon their spouse’s death [

18,

28]. Kanyamurwa

et al. conducted a study of farming households in Uganda to assess the gender influence on the livelihood of homes affected by AIDS and those unaffected by the disease [

21]. The investigators concluded that female-headed-households were more affected by AIDS than male-headed-households; women were more prone to losing ownership of their land and livestock [

21]. In contrast to the findings of Kanyamurwa

et al., Aliber

et al. did not detect a link between HIV/AIDS mortality and land security for females, yet, the authors still concluded that HIV/AIDS does further complicate the issue of land tenure for females [

28]. The concern for land loss amidst mounting caretaker duties for females can have direct environmental consequences either as a result of little time to devote to conservative farming techniques, or the transference of the land to owners that have no working knowledge of proper land management [

28].

5. Management of the Natural Environment

5.1. Unsustainable Use of Natural Resources

Many communities have attempted to cope with the HIV/AIDS pandemic by increasing their dependence on the physical environment as a way to maintain their livelihood. Unfortunately, this is often done in a manner that is unsustainable. The agricultural needs at present may compromise future needs; therefore, environmental health, economic viability, and overall quality of life for farmers and society may decline. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has recognized and characterized the link between HIV/AIDS and the natural environment. The FAO has cited rural Africa as especially influenced by this link, given the reliance of these communities on agricultural activities [

43]. An example of the relationship between HIV/AIDS and the natural environment is that forest reserves are being depleted at an alarming rate to generate firewood for households caring for the sick and to manufacture coffins to bury the deceased [

44]. Misiko

et al. sought to describe the trend in the abandonment of proper soil fertility management in Kenyan households afflicted by AIDS [

30]. The authors found that families consisted primarily of dependents (children less than ten years of age) and only had a maximum of two members that were involved in subsistence farming [

30]. Given the farmland labor constraints, many households had abandoned more-labor intensive traditional crops, such as millet and sorghum [

30]. The authors described how unfarmed land reverted to unmanageable plots that were eventually overrun by weedy grasses, leaving behind infertile soil [

30].

Another growing concern is the unsustainable harvesting of natural resources. Examples of other unsustainable practices that have been previously documented include uncontrolled charcoal mining, fishing, hunting, and the gathering of protected plants by individuals striving to make a living [

31,

44,

45]. One such example is the gathering and exportation of wild orchids in Tanzania. Wild orchids are considered illegal for trade in Tanzania; however, many of these edible orchids constitute a portion of the diet for neighboring Zambia [

31]. This has led to the prohibited trade and exportation of orchids to the Zambian people by Tanzanians, often orphaned youth, whose lives have been affected by HIV/AIDS [

31]. Unfortunately, the practice of orchid gathering is not viable, as it often involves uprooting the entire plant, which threatens the survival of many orchid species [

31]. Researchers conducted a study to describe these gathering practices in three rural villages of Tanzania [

32]. The researchers noted an increase in the prevalence of non-edible orchid species but a decrease in edible orchid species [

32]. This shift in orchid type is evidence of ongoing illegal exportation and the endangered existence of edible orchids in this area by individuals who have been affected by this disease [

32].

5.2. Loss of Human Capacity

The crux of the problem can often be attributed to the loss of human lives, specifically the loss of prime-age adult workers. The World Wildlife Fund, Inc., a non-governmental organization dedicated to environment conservation and restoration efforts, has cited a loss of human capacity due to HIV/AIDS as a major hindrance to preservation efforts [

46]. The organization explains that many natural areas cannot be properly protected due to a decrease in highly trained staff, including national park guards and patrol officers [

33,

46]. This has given way to an increase in unmonitored poaching of endangered species including the buffalo and elephants [

46]. Rosen

et al. conducted a study among Zambian Wildlife Authority officers to assess the influence of AIDS on worker productivity [

33]. After adjusting for age and worksite, the disease was associated with a 68% decrease (

p < 0.0001) in the amount of days on patrol, during the year of observation, compared to the previous year [

33]. The investigators also documented an overall decrease in service delivery capacity due to days of absenteeism; days were lost to attend funerals and to replace lost employees [

33]. The loss of worker productivity and rising absenteeism is yet another challenge to preserving the relationship between rural life and its impact on the environment.

7. Conclusions

HIV/AIDS continues to pose an array of concerns for sub-Saharan Africa. The spread of HIV/AIDS further strains the fragile relationship that has long existed between the local environment, social infrastructure, and rural livelihood. Changing population dynamics and a growing dependency on the environment and its resources are at the center of this crisis. Nevertheless, plausible solutions to overcome some of these problems do exist. If implemented, rural communities of sub-Saharan Africa can effectively work toward environmental preservation.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Loan Repayment Program and a graduate fellowship from The University of Texas at Austin, both granted to Oramasionwu. Frei is supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the form of a NIH/KL2 career development award (3UL1RR025767). In addition, Frei has received research grants and/or served as a scientific consultant/advisor for AstraZeneca, Forest, Ortho McNeil Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. The authors would like to thank Kyllie Ryan-Hummel for her assistance with this project.

References

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO). 2009 AIDS Epidemic Update; UNAIDS: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009. Available online: http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/JC1700_Epi_Update_2009_en.pdf accessed on 27 October 2010.

- Katabira, ET; Oelrichs, RB. Scaling up antiretroviral treatment in resource-limited settings: Successes and challenges. AIDS 2007, 21, S5–10. [Google Scholar]

- El-Sadr, WM; Abrams, EJ. Scale-up of HIV care and treatment: Can it transform healthcare services in resource-limited settings? AIDS 2007, 21, S65–70. [Google Scholar]

- AIDS and Rural Livelihoods: Dynamics and Diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa; Niehof, A; Rugalema, G; Gillespie, S (Eds.) Earthscan: London, UK, 2010.

- Dorward, AR; Mwale, I; Tuseo, R. Labor market and wage impacts of HIV/AIDS in Rural Malawi. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Pol 2006, 28, 429–439. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, LM; Twine, W; Patterson, L. “Locusts are now our beef”: Adult mortality and household dietary use of local environmental resources in rural South Africa. Scand. J. Public Health Suppl 2007, 69, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter, N; Koekemoer, R; Jagals, P. A pilot assessment of water, sanitation, hygiene and home-based care services for people living with HIV/AIDS in rural and peri-urban communities in South Africa. Water Sci. Technol 2007, 56, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lule, JR; Mermin, J; Ekwaru, JP; Malamba, S; Downing, R; Ransom, R; Nakanjako, D; Wafula, W; Hughes, P; Bunnell, R; et al. Effect of home-based water chlorination and safe storage on diarrhea among persons with human immunodeficiency virus in Uganda. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg 2005, 73, 926–933. [Google Scholar]

- Chapoto, A; Jayne, TS. Impact of AIDS-related mortality on farm household welfare in Zambia. Econ. Dev. Culture Change 2008, 56, 327–373. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, MO; Booysen, FL. Health and economic impact of HIV/AIDS on South African households: A cohort study. BMC Public Health 2003, 3, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Fagbemissi, R; Price, LL. HIV/AIDS orphans as farmers: Uncovering pest knowledge differences through an ethnobiological approach in Benin. NJAS-Wageningen J. Life Sci 2008, 56, 241–259. [Google Scholar]

- Thangata, PH; Hildebrand, PE; Kwesiga, F. Predicted impact of HIV/AIDS on improved fallow adoption and rural household food security in Malawi. Sustain. Dev 2007, 15, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Kaschula, S. Wild foods and household food security responses to AIDS: Evidence from South Africa. Popul. Environ 2008, 29, 162–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mmbaga, EJ; Leyna, GH; Hussain, A; Mnyika, KS; Sam, NE; Klepp, KI. The role of in-migrants in the increasing rural HIV-1 epidemic: Results from a village population survey in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania. Int. J. Infect. Dis 2008, 12, 519–525. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, SJ; Collinson, MA; Kahn, K; Drullinger, K; Tollman, SM. Returning home to die: Circular labour migration and mortality in South Africa. Scand. J. Public Health Suppl 2007, 69, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Coffee, M; Lurie, MN; Garnett, GP. Modelling the impact of migration on the HIV epidemic in South Africa. AIDS 2007, 21, 343–350. [Google Scholar]

- Schatz, E; Ogunmefun, C. Caring and contributing: The role of older women in rural South African multi-generational households in the HIV/AIDS era. World Dev 2007, 35, 1390–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, DC; Jacobsen, KH; Komwa, MK. A qualitative study of the impact of HIV/AIDS on agricultural households in Southeastern Uganda. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 2113–2138. [Google Scholar]

- Kipp, W; Tindyebwa, D; Rubaale, T; Karamagi, E; Bajenja, E. Family caregivers in rural Uganda: The hidden reality. Health Care Women Int 2007, 28, 856–871. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle, KL; Jewkes, RK; Brown, HC; Gray, GE; McIntryre, JA; Harlow, SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet 2004, 363, 1415–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Kanyamurwa, JM; Ampek, GT. Gender differentiation in community responses to AIDS in rural Uganda. AIDS Care 2007, 19, S64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, L; Twine, W; Johnson, A. Adult mortality and natural resource use in rural South Africa: Evidence from the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance Site. Soc. Nat. Resour 2011, 24, 256–275. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, L. AIDS and kitchen gardens: Insights from a village in Western Kenya. Popul. Environ 2008, 29, 133–161. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, E; Unruh, J. Demarcating forest, containing disease: Land and HIV/AIDS in southern Zambia. Popul. Environ 2008, 29, 108–132. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, DK; Shackleton, CM. Is HIV/AIDS jeopardizing biodiversity? Environ. Conserv 2009, 36, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, SS; Bulirwa, E; Kisseka, E. AIDS and agricultural production. Report of a land utilization survey, Masaka and Rakai districts of Uganda. Land Use Policy 1993, 10, 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ebanyat, P; de Ridder, N; de Jager, A; Delve, RJ; Bekunda, MA; Giller, KE. Drivers of land use change and household determinants of sustainability in smallholder farming systems of Eastern Uganda. Popul. Environ 2010, 31, 474–506. [Google Scholar]

- Aliber, M; Walker, C. The impact of HIV/AIDS on land rights: Perspectives from Kenya. World Dev 2006, 34, 704–727. [Google Scholar]

- Drimie, S. HIV/AIDS and land: Case studies from Kenya, Lesotho and South Africa. Dev. S. Afr 2003, 20, 647–658. [Google Scholar]

- Misiko, M. An ethnographic exploration of the impacts of HIV/AIDS on soil fertility management among smallholders in Butula, western Kenya. NJAS-Wageningen J. Life Sci 2008, 56, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Challe, JF; Price, LL. Endangered edible orchids and vulnerable gatherers in the context of HIV/AIDS in the southern highlands of Tanzania. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed 2009, 5, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Challe, JFX; Struik, PC. The impact on orchid species abundance of gathering their edible tubers by HIV/AIDS orphans: A case of three villages in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. NJAS-Wageningen J. Life Sci 2008, 56, 261–279. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, S; Hamazakaza, P; Feeley, F; Fox, M. The impact of AIDS on government service delivery: The case of the Zambia Wildlife Authority. AIDS 2007, 21, S53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, S; Niehof, A; Rugalema, G. AIDS in Africa: Dynamics and Diversity of Impacts and Response. In AIDS and Rural Livelihoods: Dynamics and Diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa; Niehof, A, Rugalema, G, Gillespie, S, Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Calleja, JM; Gouws, E; Ghys, PD. National population based HIV prevalence surveys in sub-Saharan Africa: Results and implications for HIV and AIDS estimates. Sex Transm Infect 2006, 82(Suppl 3). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, DP; Blower, S. How far will we need to go to reach HIV-infected people in rural South Africa? BMC Med 2007, 5, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, O. Human Resource Requirements for Scaling up Antiretroviral Therapy in Low Resource Countries. In Scaling up Treatment for the Global AIDS Pandemic: Challenges and Opportunities; Curran, J, Debas, H, Arya, M, Kelley, P, Knobler, S, Pray, L, Eds.; National Academies Press (Board of Global Health): Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bisimwa, G; Mambo, T; Mitangala, P; Schirvel, C; Porignon, D; Dramaix, M; Donnen, P. Nutritional monitoring of preschool-age children by community volunteers during armed conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Food Nutr. Bull 2009, 30, 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- US Census Bureau. The AIDS Pandemic in the 21st Century; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. Available online: http://www.census.gov/ipc/prod/wp02/wp02-2.pdf accessed on 27 October 2010.

- Stanecki, KA; Way, PO. The Demographic Impact of HIV/AIDS, Perspectives from the World Population Profile: 1996; IPC Staff Paper 86; International Programs Center, US Bureau of the Census: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diagnoses of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2008; CDC: Atlanta, USA, 2010. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2008report/index.htm accessed on 26 October 2010.

- Du Preez, C; Niehof, A. Impacts of AIDS-Related Morbidity and Mortality on Non-Urban Households in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. In AIDS and Rural Livelihoods: Dynamics and Diversity in Sub-Saharan Africa; Niehof, A, Rugalema, G, Gillespie, S, Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). AIDS: A Threat to Rural Africa; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2001. Available online: http://www.fao.org/FOCUS/E/aids/aids1-e.htm accessed on 27 October 2010.

- Human Health and Forests: A Global Overview of Issues, Practice and Policy; Colfer, CJP (Ed.) Earthscan: London, UK, 2008.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nation (FAO). The State of Food Insecurity in the World, 2008: High Food Prices and Food Security—Threats and Opportunities; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/i0291e/i0291e00.htm accessed on 1 November 2010.

- World Wildlife Fund, Inc. HIV/AIDS and the Environment: Impacts of AIDS and Ways to Reduce Them; World Wildlife Fund Inc.: Washington, USA, 2007. Available online: http://www.worldwildlife.org/what/communityaction/people/phe/WWFBinaryitem7051.pdf accessed on 27 October 2010.

- Jama, B; Zeila, A. Agroforestry in the Drylands of Eastern Africa: A Call to Action; ICRAF Working Paper—No. 1; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).