Mothers and Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Review of Treatment Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

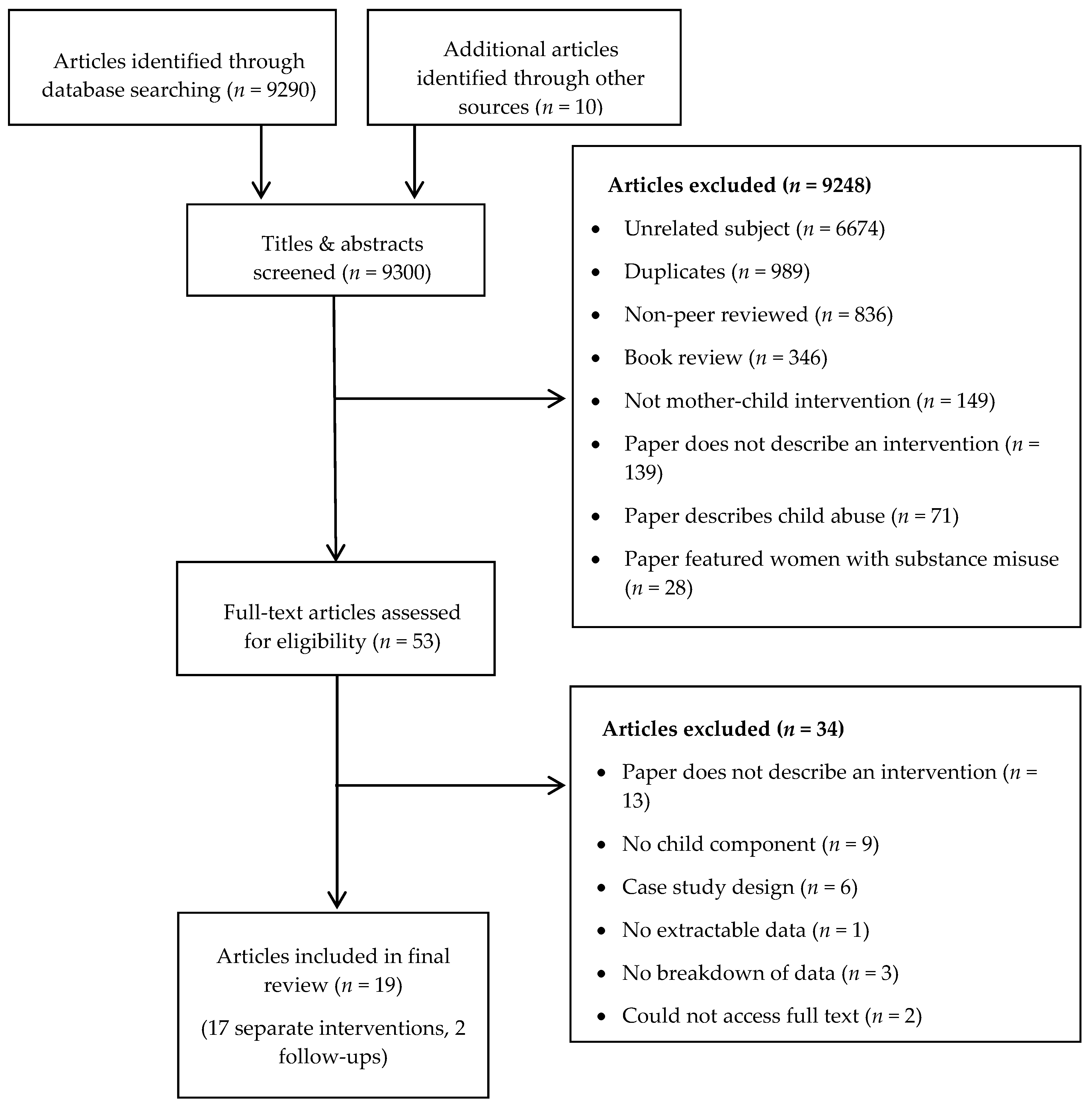

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Overview of Featured Interventions

3.2.1. Separate Interventions

3.2.2. Joint Interventions

3.2.3. Combined Interventions

3.3. Outcomes of Interventions

3.3.1. Separate Interventions

3.3.2. Joint Interventions

3.3.3. Combined Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Theory of Change

4.2. Limitations of This Review

4.3. Future Research and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

|---|---|---|

| famil * | intimate partner violence | Intervention |

| parent * | domestic violence | Systemic |

| mother | partner homicide | therap * |

| father | abuse | Group |

| caregiver | domestic abuse | individual |

| guardian | sexual abuse | mediation |

| family relation * | emotional abuse | psych * intervention |

| mother-child dyad | physical abuse | prevention |

| rape | ||

| batter * |

- Inclusion:

- All languages

- All study types

- All sample recruitment locations

- All treatment modalities

- Exclusion:

- Violence against males

- Father-child interventions

- Children born through prostitution

- Women with substance misuse issues

- Databases:

- Medline/PubMED

- PsycINFO

- Cochrane database

- PILOTS

- Hand searches of journals:

- Violence Against Women

- Family & Intimate Partner Violence Quarterly

- Journal of Family Violence

- Journal of Interpersonal Violence

- Partner Abuse

- Trauma, Violence & Abuse

- Anger, Aggression & Violence

- Author

- Year

- Journal

- Study location

- Study design

- Study population

- Sample size

- Age of mothers/children

- Aims

- Methods/Intervention outline

- Assessment time points

- Outcome Measures

- Analyses

- Results

- GRADE

References

- World Health Organization. Violence Against Women. Fact Sheet No. 239. 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 24 August 2018).

- UK Government. Domestic Violence and Abuse. 2018. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/domestic-violence-and-abuse (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Garcia-moreno, C.; Jansen, H.A.F.M.; Ellsberg, M.; Heise, L.; Watts, C.H. Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings from the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence. Lancet 2006, 368, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nybergh, L. Exploring Intimate Partner Violence among Adult Women and Men in Sweden; Institute of Medicine, University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Breiding, M.J.; Black, M.C.; Ryan, G.W. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Intimate Partner Violence in Eighteen, U.S. States/Territories, 2005. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, C.L.; Ching, W.M.; Tong, W.L.; Chan, K.L.; Tsui, K.L.; Kam, C.W. 1700 Victims of intimate partner violence: Characteristics and clinical outcomes. Hong Kong Med. J. 2008, 14, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, P.G.; Crooks, C.V.; Wolfe, D.A. Legal and policy responses to children exposed to domestic violence: The need to evaluate intended and unintended consequences. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 6, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, R.; Widom, C.S.; Browne, K.; Fergusson, D.; Webb, E.; Janson, S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 2009, 373, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaney, J. Research Review: The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children. Irish Probat. J. 2015, 12, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wathen, C.N.; MacMillan, H.L. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: Impacts and interventions. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2013, 18, 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Behind Closed Doors—The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, K.W.; Krueger, C.E.; Wilson, C. Relationships Between Maternal Emotion Regulation, Parenting, and Children’s Executive Functioning in Families Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2012, 27, 3532–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Lynch, S.; Banyard, V.; DeVoe, E.; Halabu, H. Community-based intervention for children exposed to intimate partner violence: An efficacy trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 75, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullender, A.; Hague, G.; Imam, U.; Kelly, L.; Malos, E.; Regan, L. Children’s Perspectives on Domestic Violence; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Miller, L.E. Intervention to reduce traumatic stress following intimate partner violence: An efficacy trial of the Moms’ Empowerment Program (MEP). Psychodyn. Psychiatry 2013, 41, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pico-Alfonso, M.A.; Garcia-Linares, M.; Celda-Navarro, N.; Blasco-Ros, C.; Echeburúa, E.; Martinez, M. The Impact of Physical, Psychological, and Sexual Intimate Male Partner Violence on Women’s Mental Health: Depressive Symptoms, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, State Anxiety, and Suicide. J. Womens Health 2006, 15, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, A.; Van Horn, P.; Ghosh Ippen, C. Toward evidence-based treatment: Child-parent psychotherapy with preschoolers exposed to marital violence. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2005, 44, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Øverlien, C. Children exposed to domestic violence: Conclusions from the literature and challenges ahead. J. Soc. Work 2010, 10, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, E.; Bonomi, A.; Anderson, M.; Rivara, F.P. The intergenerational transmission of intimate partner violence. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2009, 163, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouriles, E.N.; McDonald, R.; Spiller, L.; Norwood, W.D.; Swank, P.R.; Stephens, N.; Ware, H.; Buzy, W.M. Reducing conduct problems among children of battered women. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2001, 69, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid-Cunningham, A.R. Parent—Child relationship and mother’s sexual assault history. Violence Against Women 2009, 15, 920–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturge-apple, M.L.; Davies, P.T.; Cicchetti, D. Mother’s parenting practices as explanatory mechanisms in associations between interparental violence and child adjustment. Partner Abuse 2011, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Maddoux, J.A.; Liu, F.; Symes, L.; Mcfarlane, J.; Paulson, R.; Binder, B.K.; Fredland, N.; Nava, A.; Gilroy, H. Partner Abuse of Mothers Compromises Children’s Behavioral Functioning Through Maternal Mental Health Dysfunction: Analysis of 300 Mother-Child Pairs. Res. Nurs. Health 2016, 39, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levendosky, A.; Graham-Bermann, S. Trauma and parenting in battered women: An addition to an ecological model of parenting. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2000, 3, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osofsky, J. Prevalence of Children’s Exposure to Domestic Violence and Child Maltreatment: Implications for Prevention and Intervention. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 6, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.; Buckley, H.; Whelan, S. The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse Negl. 2008, 32, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Miller-Graff, L. Community-based intervention for women exposed to intimate partner violence: a randomized control trial. J. Fam. Psychol. 2015, 29, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, C.S.; Meadows, A.L.; Kaufman, J. Interventions for intimate partner violence: Review and implications for evidence-based practice. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2009, 40, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, P.T. Therapeutic interventions for children who have witnessed domestic violence. In Compelling Counselling Interventions: Celebrating VISTAS’ Fifth Anniversary; Americal Counseling Association: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008; pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rizo, C.F.; Macy, R.J.; Ermentrout, D.M.; Johns, N.B. A review of family interventions for intimate partner violence with a child focus or child component. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2011, 16, 144–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, G.J.; Wilkens, S.L.; Lieberman, A.F. The influence of domestic violence on preschooler behavior and functioning. J. Fam. Violence 2007, 22, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, J.M.; Groff, J.Y.; O’Brien, J.A.; Watson, K. Behaviors of children following a randomized controlled treatment program for their abused mothers. Issues Compr. Pediatr. Nurs. 2005, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, A.E.; Shanahan, M.E.; Barrios, Y.V.; Macy, R.J. A Systematic Review of Interventions for Women Parenting in the Context of Intimate Partner Violence. Trauma Violence Abuse 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, P.; Wolfe, D.; Wilson, S. Children of Battered Women; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brozek, J.L.; Akl, E.A.; Compalati, E.; Kreis, J.; Terracciano, L.; Fiocchi, A.; Ueffing, E.; Andrews, J.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Meerpohl, J.J.; et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines Part 3 of 3 the GRADE approach to developing recommendations. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 66, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brozek, J.L.; Akl, E.A.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Lang, D.; Jaeschke, R.; Williams, J.W.; Phillips, B.; Lelgemann, M.; Lethaby, A.; Bousquet, J.; et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines: Part 1 of 3. An overview of the GRADE approach and grading quality of evidence about interventions. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 64, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brozek, J.L.; Akl, E.A.; Jaeschke, R.; Lang, D.M.; Bossuyt, P.; Glasziou, P.; Helfand, M.; Ueffing, E.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Meerpohl, J.; et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations in clinical practice guidelines: Part 2 of 3. The GRADE approach to grading quality of evidence about diagnostic tests and strategies. Allergy Eur. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 64, 1109–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Basu, A.; Malone, J.C.; Levendosky, A.A.; Dubay, S. Longitudinal Treatment Effectiveness Outcomes of a Group Intervention for Women and Children Exposed to Domestic Violence. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2009, 2, 90–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.D.; Mathis, G.; Mueller, C.W.; Issari, K.; Atta, S.S. Community-based treatment outcomes for parents and children exposed to domestic violence. J. Emot. Abuse 2008, 8, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Miller-Graff, L.E.; Howell, K.H.; Grogan-Kaylor, A. An Efficacy Trial of an Intervention Program for Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2015, 46, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macmillan, K.; Harpur, L. An Examination of Children Exposed to Marital Violence Accessing a Treatment Intervention. J. Emot. Abuse 2003, 3, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldman-Levi, A.; Weintraub, N. Efficacy of a crsis intervention in improving mother-child interaction and children’s play functioning. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2015, 69, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.; Landreth, G. Intensive filial therapy with child witnesses of domestic violence: A comparison with individual and sibling group play therapy. Int. J. Play Ther. 2003, 12, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouriles, E.; McDonald, R.; Rosenfield, D.; Stephens, N.; Corbitt-Shindler, D.; Miller, P.C. Reducing conduct problems among children exposed to intimate partner violence: A randomized clinical trial examining effects of Project Support. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 77, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R.; Jouriles, E.; Skopp, N. Reducing conduct problems among children brought to women’s shelters: Intervention effects 24 months following termination of services. J. Fam. Psychol. 2006, 20, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, E. Domestic Abuse, Recovering Together (DART): Evaluation Report; NSPCC: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, E.; Belton, E.; Barnard, M.; Cotmore, R.; Taylor, J. Recovering from Domestic Abuse, Strengthening the Mother–Child Relationship: Mothers’ and Children’s Perspectives of a New Intervention. Child Care Pract. 2013, 19, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, P.T. Differential therapeutic outcomes of community-based group interventions for women and children exposed to intimate partner violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2011, 26, 2457–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.; Mannarino, A.; Iyengar, S. Community treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder for children exposed to intimate partner violence: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011, 165, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, M.; Egan, M.; Gooch, M. Conjoint Interventions for Adult Victims and Children of Domestic Violence: A Program Evaluation. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2004, 14, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.; Kay, S.; George, J.; King, P. Treating Children Exposed to Domestic Violence. J. Emot. Abuse 2003, 3, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A.; Ghosh, I.; Van Horn, P. Child-Parent Psychotherapy: 6-Month Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2006, 45, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist; Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- McAlister Groves, B. Mental health services for children who witness domestic violence. Futur. Child 1999, 9, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øverlien, C.; Hyden, M. Children’s Actions when Experiencing Domestic Violence. Childhood 2009, 16, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Domestic violence, children’s agency and mother-child relationships: Towards a more advanced model. Child Soc. 2015, 29, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, A. Transactional Models in Early Social Relations. Hum. Dev. 1975, 18, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.; Altman, D.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 Statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 8, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Landreth, G. Therapeutic limit setting in the play therapy relationship. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2002, 33, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, {Reference] | Intervention Recruitment Locations | Study Design | Age of Children | Sample Size | Study Aims | Brief Intervention Description | Control Group | Assessment Time Points | Outcome Measures | Findings | GRADE Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Separate interventions | |||||||||||

| Basu et al. 2009 [38] | USA Community | Randomized group intervention | 3–12 | Children: 20 Mothers: 36 | To implement a community-based, manualized, psychoeducational intervention program targeting mothers and children exposed to IPV | 10 weeks, 1.5 h/week for mothers, 1 h/week for children. Psychoeducational: Focus on different theme relating to IPV | Waitlist | Pre- & 3 + 6-month FU | Mothers: severity of violence, distress, depression, trauma Children: perceived competence & social acceptance, feelings toward IPV at home | No significant differences for depression, anxiety or trauma symptoms across the groups. The intervention group had the lowest levels of depression and anxiety symptoms compared to both the intervention and early termination groups over time. Children in the CG showed a decrease in anxiety and depression symptoms relative to the other groups immediately post intervention but not in the 3- or 6-month assessments. There were no significant differences for trauma symptoms. | 3 |

| Becker at al., 2008 [39] | USA Community | Non-randomized intervention | 3–17 | Children: 106 Mothers: 56 | To implement a culturally influenced intervention program involving a sample largely identifying as from Asian and Pacific Island descent. | 12 weeks, 1.5 h/week. Focus on different theme relating to IPV | - | Pre- & post-intervention | Mothers: IPV related skills, parenting practices Children: IPV related skills, behavior checklist | Children had significant improvement in ratings of violence-related from pre-post treatment. Significant decrease in internalizing and externalizing scores. Significant decrease in the proportion of children with clinically significant posttreatment psychopathology. Parents were observed to have significant improvement in their IPV related skills and parenting practices. | 3 |

| Graham-Bermann, et al., 2015 [40] | USA IPV shelters | RCT | 4–6 | Mothers & children: 120 | To compare the adjustment of children exposed to severe IPV who participated in the Pre Kids’ Club (PKC) while their mothers participated in the Mom’s Empowerment Program (MEP) | 5 weeks, 2 sessions/week. Mothers: to enhance social and emotional adjustment. Children: each session focuses on different topics related to IPV | Waitlist | Pre- & post- intervention 8 months FU | Mothers: severity of violence. Children: behavior checklist (internalizing only) | There was no statistically significant decrease in internalizing problems over time in the control group. For female children in the treatment group, there was a statistically significant decrease in internalizing problems at the 8-month follow up point. Under a per-protocol specification, there were statistically significant differences between the treatment and comparison groups. | 3 |

| Macmillan & Harpur, 2003 [41] | Canada Community | Non-randomized intervention | 6–12 | Children: 47 Mothers: 39 | To describe the well-being and functioning of this sample of children and parents who are living in the community and seeking out treatment. | 10 weeks, 1.5 h/week. Children: addressing posttraumatic stress issues, IPV related skills, relaxation. Mothers: promoting relationship building, positive discipline practices. | - | Pre- & post- intervention | Parents: parenting stress Children: behavior checklist, depression, anxiety, trauma-related sequelae, understanding of abuse | Children’s behavior problems (externalizing, internalizing, and total score) were significantly lowered, while children’s scores on the knowledge forms were significantly increased. Parenting stress significantly lowered. | 3 |

| Joint interventions | |||||||||||

| Jouriles et al., 2001 [20] | USA IPV shelters | RCT | 4–9 | Mothers & children: 36 | An experimental evaluation of a programme designed to reduce conduct problems of children of domestic violence victim mothers. | 8 months, 1.5 h/week. Child management skills | Monthly telephone calls | Pre-intervention 4, 8, 12, 16 months FU | Mothers: severity of violence Children: behavior checklist Mothers & children: child management | Significant improvement in externalizing over time. Slightly higher mean level of child management skills at assessment 3, and improving more rapidly in families in treatment condition. Mother’s psychological distress diminished over time. Level of conduct problems in intervention arm brought to within normal range, mothers gained more rapid and greater improvements in child management skills. | 3.5 |

| Waldman Levi & Weintraub, 2015 [42] | Israel IPV shelters | Non-randomized intervention | 3–5 | Children: 37 Mothers: 37 | To examine the efficacy of filial therapy for mothers and their children in IPV shelters. | 8 weeks, 30min/week. Opening (5 mins), joint play (20 mins), closure & separation (5 mins). | Free play time | Pre- & post- intervention | Mothers & children: interactive behavior Children: play skills, playfulness. | Children’s play skills significantly improved in the FI-OP group for sensitivity and limit setting. No differences fond in involvement, reciprocity, negative states. Children’s play skills significantly improved, but not regarding material management or participation. No difference in playfulness between groups. | 2.5 |

| Smith & Landreth, 2003 [43] | USA IPV shelters | Non-randomized intervention | 4–10 | Children: 11 Mothers: 11 | To determine the effectiveness of intensive filial therapy as a method of intervention with child witnesses of domestic violence. | Filial therapy 2–3 weeks, 12 sessions, 1.5 h/session Combined parent training session and parent-child play session. | Sibling group therapy | Pre- & post intervention | Mothers & children: empathy Children: behavior checklist, self-concept. | Intervention group demonstrated significant improvement on all measures. Children in the intensive individual play therapy group scored significantly higher in self-concept than children in the filial therapy. There were no significant differences between the intensive filial therapy experimental group and the intensive sibling group play therapy comparison group on self-concept scores. Mothers achieved significantly higher levels of positive behavior. | 3 |

| Jouriles et al., 2009 [44] | USA IPV shelters | RCT | 4–9 | Mothers & children: 66 | To replicate and extend findings from initial findings (Jouriles et al. 2001). | 12 months, weekly home visits. Child management skills. | Month-ly phone calls | Pre-intervention 4, 8, 12, 16, & 20 months FU | Mothers: severity of violence, parenting, psychological aggression, psychiatric symptoms, traumatic symptoms. Children: conduct problems, frequency of behaviors, oppositional behavior. | Child conduct problems decreased more rapidly in the intervention group. For the follow-up period, conduct problems continued to decrease in the intervention group, but not in the comparison group. Although oppositional child behavior decreased more slowly than the other measures of child conduct problems, child behavior still decreased more rapidly in the intervention group than the comparison group during both the intervention and follow-up periods. During the intervention period, inconsistent and harsh parenting behaviors decreased in the Project Support group, and in the comparison group, with more rapid decreases in the Project Support group. During the follow-up period, no changes in inconsistent and harsh parenting behaviors emerged in either of the groups. Maternal psychiatric symptoms decreased during the intervention period in the Project Support group, and in the comparison group. | 4 |

| Macdonald et al., 2006 [45] | Follow-up | Mothers & children: 36 | To assess the effects of Project Support on children’s conduct problems 24 months following the termination of services (32 months following shelter departure). | 24 months | Mothers: aggression, contact w/partner, recurrence of violence. Children: oppositional behavior, behavior checklist, internalizing problems. | Only 31% of children still in clinical level of conduct problems at either 16 months/32-month assessment points (compared to 71% in comparison group). Externalizing scale scores for intervention and comparison conditions at the 24-month follow-up assessment did not differ significantly from one another. Mean levels of internalizing problems did not differ between the treatment and comparison groups at the 24-month follow-up assessment. However, there were differences in the proportion of children in each group exhibiting clinical levels of internalizing problems. | 3.5 | ||||

| Combined interventions | |||||||||||

| Graham-Bermann et al., 2007 [13] | USA IPV shelters | RCT | 6–12 | Mothers & children: 181 | To promote alternatives to aggression and address children’s beliefs about violence | 10 weeks, Mothers: building parenting competence Children: understanding IPV-related behavior | Waitlist | Pre- & post-intervention 8-month FU | Mothers: severity of violence, social desirability Children: behavior checklist, attitudes about IPV | Individual CM children displayed significantly greater improvement from baseline to post-intervention relative to controls in externalizing behavior problems and attitudes in the two-level model comparing change in individuals assigned to different conditions. Individual children in the CM condition made significantly greater changes in externalizing behavior problems from posttreatment to follow-up when compared with children in the CO condition. Significant deterioration in attitudes for individual CO children, suggesting that mothers may influence their children’s beliefs and attitudes about violence after participating in the intervention programme themselves | 4 |

| Graham-Bermann & Miller, 2013 [15] | USA IPV shelters | RCT | 6–12 | Mothers & children: 181 | To assess the efficacy of a group intervention in relieving traumatic stress symptoms for women exposed to IPV. | 10 weeks Mothers: building parenting competence Children: process feelings re: IPV, IPV related skills. | Waitlist | Pre- & post- intervention 8-month FU | Mothers: severity of violence, PTSD, social desirability Children: - | The more social desirability the less reported trauma symptoms. Significant reduction in traumatic stress symptoms for all 3 conditions from baseline to end of treatment. From baseline to follow up was bigger change. | 3 |

| Lieberman et al., 2005 [17] | USA Mixed clinical locations | RCT | 3–5 | Children: 75 Mothers: 75 | To evaluate the efficacy of child-parent psychotherapy (CPP) compared with case management plus separate treatment. | CPP 50 weeks, 60min/week. Children: free play Mothers: managing the child and their experiences of IPV Weekly joint sessions to enhance interactions | Case manage-ment & usual care | Pre-intervention, 6 months into treatment | Children: exposure to community violence: behavior checklist, trauma. Mothers: life stress, psychiatric symptoms, traumatic stress disorder. | Intervention group had a significant reduction in the number of trauma symptoms, whereas the comparison group did not. Significant reduction in behavior problems. Significant reductions in maternal avoidant symptoms for the intervention group post-intervention. Decline in PTSD diagnosis for mothers in both groups, although not statistically significant. | 4 |

| Smith, 2016 [46] | Wales | Non-randomized intervention | 7–11 | Children: 147 Mothers: 147 | To enhance the mother–child relationship, in addition to supporting other aspects of their recovery. | 10 weeks, 2.5 hrs. Increase mother’s confidence in parenting. | - | Pre- & post-intervention | Mothers: self-esteem, locus of control Children: self-esteem, well-being Mothers & children: acceptance and rejection | Mothers had significantly greater self-esteem, more confidence in their parenting abilities and more control over their child’s behavior. They were also more affectionate to their child. Children experienced fewer emotional and behavioral difficulties following DART. Children appeared to be experiencing significantly fewer emotional and behavioral difficulties following DART. The children’s self-esteem scores improved but this was not statistically significant. | 3 |

| McWhirter, 2011 [48] | USA Family homeless shelter | Randomised group intervention | 6–12 | Children: 48 Mothers: 46 | To assess the clinical effectiveness of emotion-focused and goal-oriented treatments to reduce IPV and increase psychosocial well-being of women and children previously exposed to IPV | 5 weeks, 1 hr/week mothers; 45min/week separate child sessions + 60min mother-child group session. Assigned to either emotion-focused or goal-oriented for both parts. | Active control | Pre- & post- intervention | Mothers: family conflict, family bonding, quality of social support, depression, self-efficacy, readiness to change, alcohol use. Children: general psychological well-being, peer conflict, family conflict, self-esteem. | Children in both groups reported decreases in family and peer conflict and increases in state of emotional well-being and self-esteem. Women in both groups reported decreases in depression and increases in family bonding and self-efficacy. Significantly greater decreases in family conflict were reported among goal-oriented participants and significantly greater increases in social support were reported among emotion-focused participants. | 4 |

| Cohen et al., 2011 [49] | USA Community IPV center | RCT | 7–14 | Children: 124 Mothers: 124 | To test whether abbreviated TF-CBT would improve children’s total IPV-related symptoms significantly more than usual care: child-centered therapy (CCT). | Individual TF-CBT. 8 weeks, 45mins/week. Developing positive coping strategies in separate sessions. 2 joint sessions to share IPV experiences. | Usual care | Pre- & post-intervention | Children: trauma, anxiety, depression, behavior checklist, cognitive functioning, verbal & non-verbal intelligence. | The intervention group experienced significantly greater improvements in overall trauma score, hyperarousal, and anxiety. | 4 |

| Sullivan et al., 2004 [50] | USA Community | Non-randomized intervention | 8–16 | Children: 79 Mothers: 46 | To address the needs of parents and children regarding coping abilities, parenting skills, safety planning skills, and the effects of post violence stress | 9 weeks. Focus on different theme relating to IPV | - | Pre- & post- intervention | Mothers: parenting stress Children: behavior checklist, trauma symptoms, anxiety, depression, anger, dissociation, self-blame. | For child behavior checklist, only 3 of the 14 measures were significantly reduced from pre-test to post-test: anxious or depressive behaviors, internalizing behaviors, and externalizing behaviors. Findings suggest the intervention programme significantly reduced trauma symptoms in the clinical subsample and significantly reduced the Anger subscale in the entire sample. Within the parenting stress scale child domain: adaptability, mood, reinforcing parent, and distractibility or hyperactivity were significant. In the parent domain, isolation, life stress, and health were significantly improved at post-test. However, the findings on the latter two subscales may lack clinical significance because both the pre-test and post-test health scores were in the non-clinical range and both the pre-test and post-test life stress scores continued to score in the clinical range. Children’s self-blame was significantly reduced at post-test in the overall sample. | 2 |

| Carter et al., 2003 [51] | USA IPV Violence programme | Non-randomized intervention | 4–18 | Children: 192 Parents: 64 | To build safety planning skills, self-esteem, ways of expressing feelings, prosocial skills, conflict resolution skills, parent-child relationship skills, identify and strengthen support systems; and provide an atmosphere for self-disclosure and therapeutic interventions to heal trauma responses. | 12 weeks, 1.5 h/week. Individual, group, family therapy services. Focus on different theme relating to IPV | - | Pre- & post-intervention | Parents: parenting stress. Children: occurrence of behavior change, ability to express emotions, social skills & adaptive functioning, PTSD, self-concept, family worries, family stereotypes. | Statistically significant decrease in intrapersonal distress, somatic symptoms, interpersonal relations, social problems and behavioral dysfunction, although interpersonal distress and interpersonal relations remained clinically significant. There were no significant changes in social skills following treatment. However, parents reported significantly fewer behavior problems in their children following treatment. Following treatment, children reported having significantly fewer worries about their moms and themselves being vulnerable to injury. | 3 |

| Lieberman et al., 2006 [52] | Follow-up | Children: 50 Mothers: 50 | Monthly telephone calls | 6-month FU | Mothers: psychiatric symptoms Children: behavior problems. | Intervention group had significant reductions in child behavior problems and maternal symptoms. Decline in symptom severity was statistically significant only for the CPP group mothers. | |||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, K.; Van Ee, E. Mothers and Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Review of Treatment Interventions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1955. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091955

Anderson K, Van Ee E. Mothers and Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Review of Treatment Interventions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(9):1955. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091955

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Kimberley, and Elisa Van Ee. 2018. "Mothers and Children Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence: A Review of Treatment Interventions" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 9: 1955. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15091955