ω-Conotoxin GVIA Mimetics that Bind and Inhibit Neuronal Cav2.2 Ion Channels

Abstract

:1. Introduction

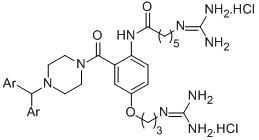

2. Results and Discussion

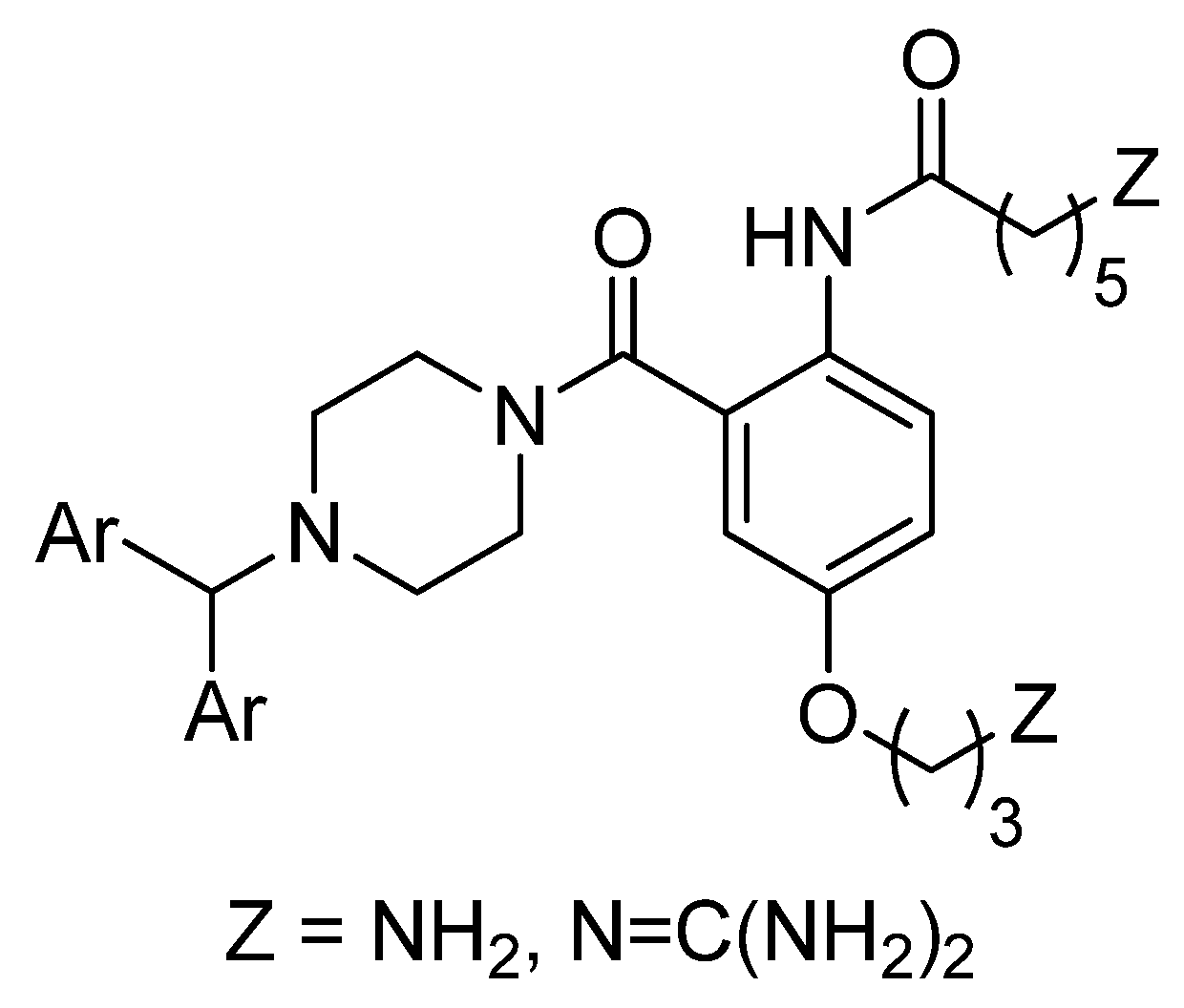

2.1. Chemistry

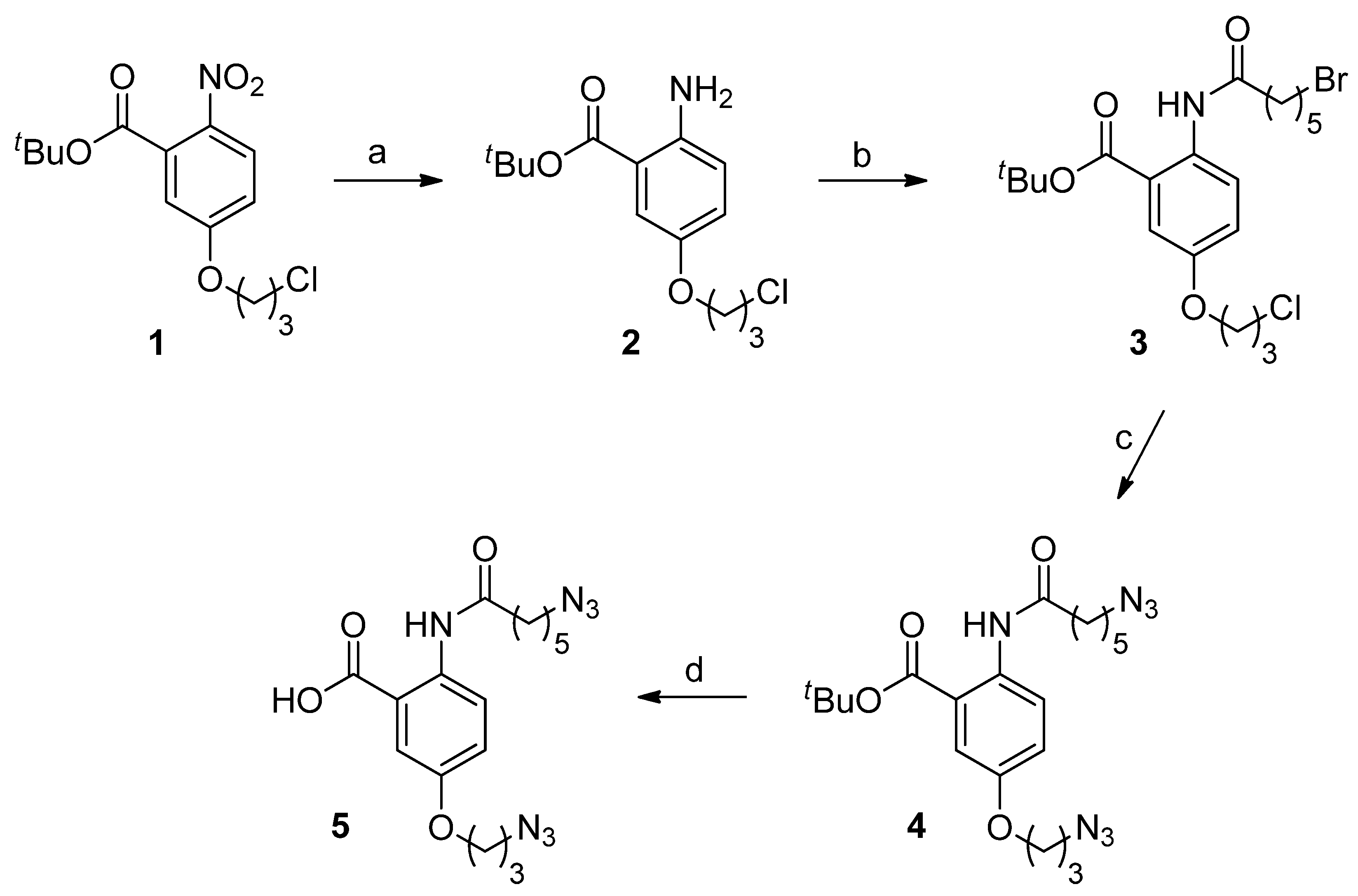

2.2. Biology

2.2.1. Radioligand Displacement Assay

| Diamino compound | EC50 Cav2.2 (μM) | Diguanidinium compound | EC50 Cav2.2 (μM) |

| 7a | 214 (160–290) | 8a | 12 (9–15) |

| 7b | 65 (50–83) | 8b | 16 (13–20) |

| 7c | weak | 8c | weak |

| 7d | weak | 8d | weak |

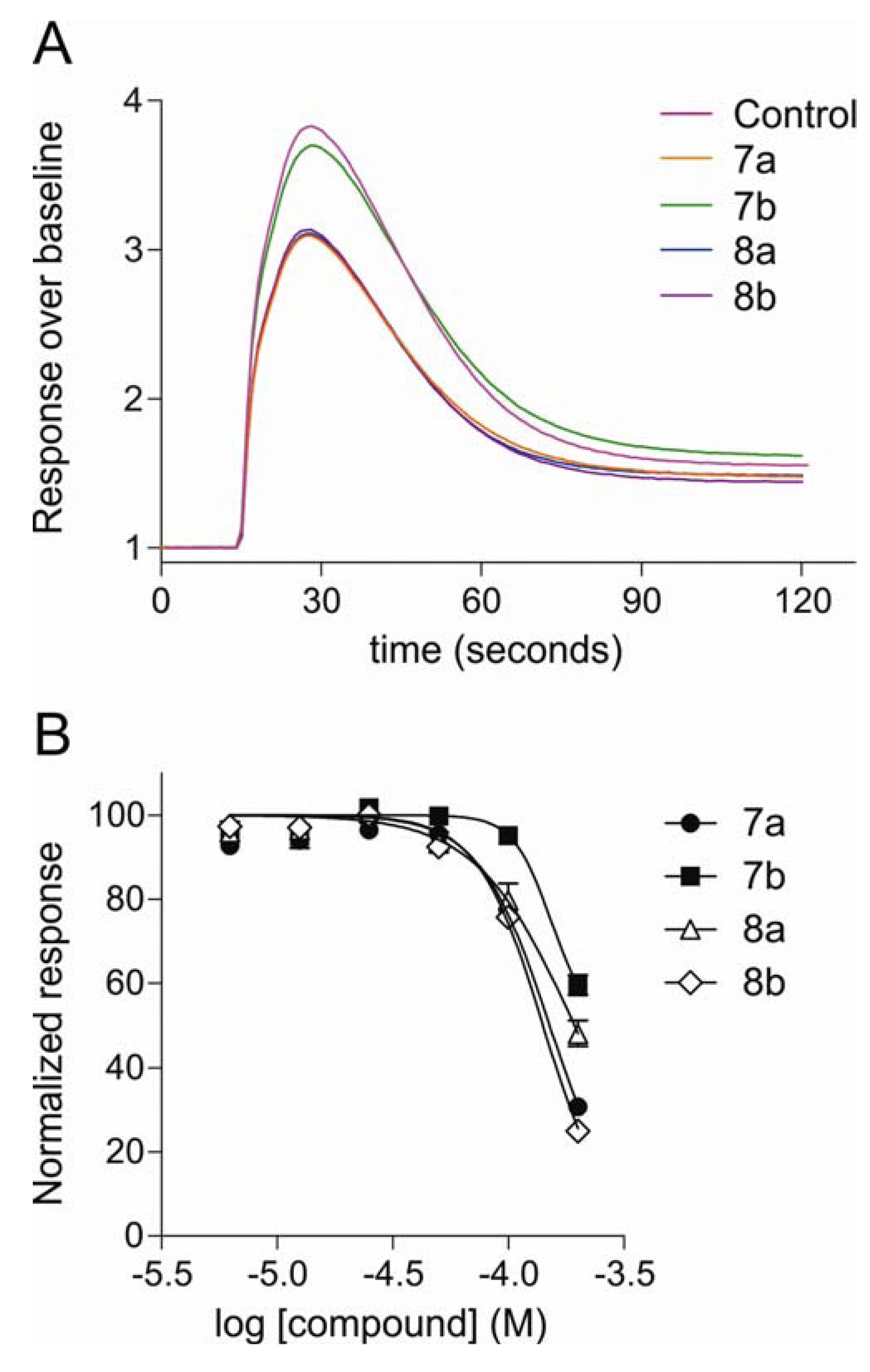

2.2.2. Inhibition of Neuroblastoma Intracellular Calcium Responses, Determined by Fluorescence Measurement of Calcium Flux

| Compound | SH-SY5Y | HEK293 |

|---|---|---|

| neuroblastoma cells | hCav2. 2 + β3 + α2δ1 | |

| 7a | 160 ± 3.6 | 232 ± 23 |

| 7b | 286 ± 66 | 288 ± 49 |

| 8a | 206 ± 50 | 299 ± 43 |

| 8b | 156 ± 10 | 156 ± 21 |

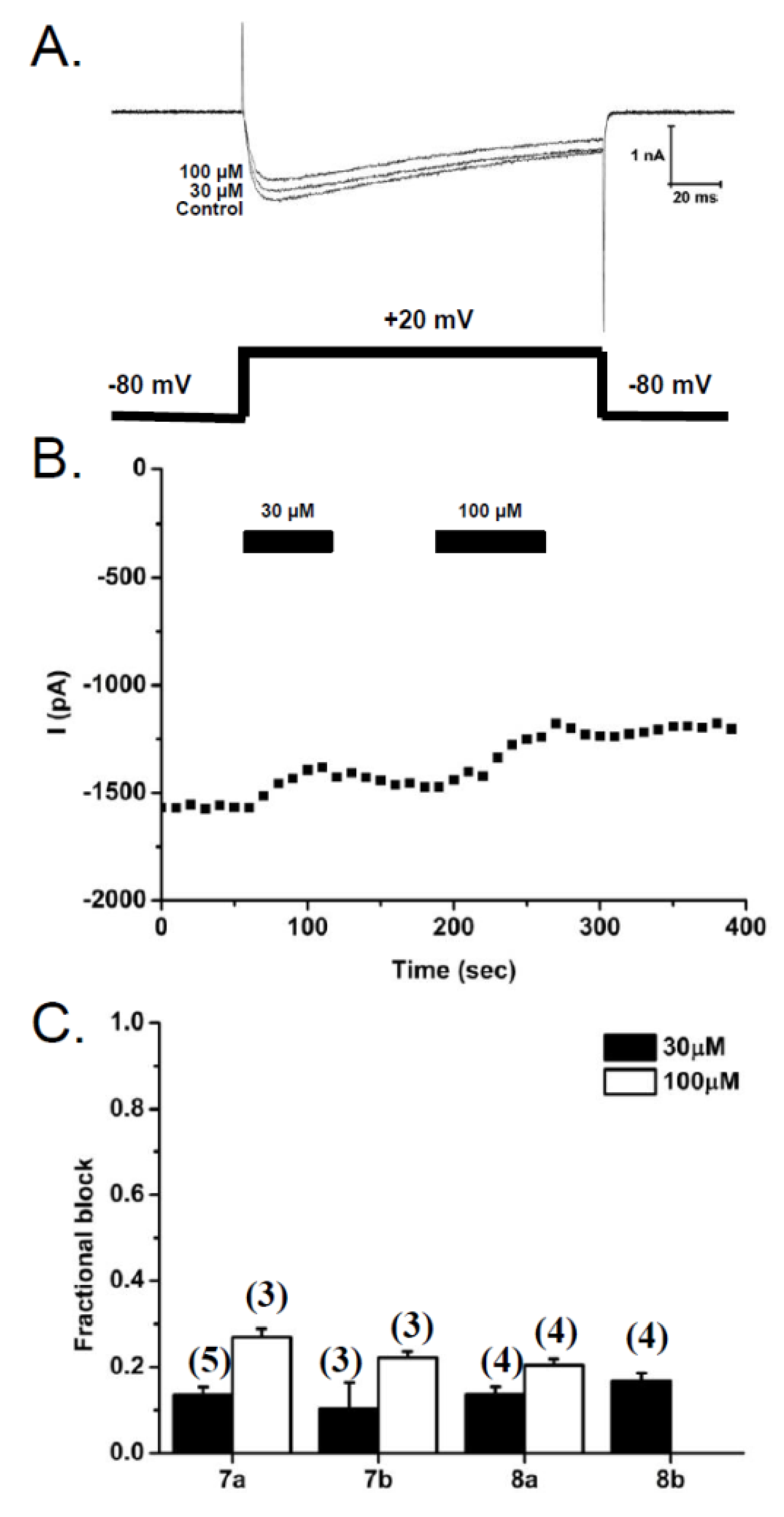

2.2.3. Patch-Clamp Electrophysiology Experiments with HEK293 Cells Expressing Cav2.2 Calcium Channels

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General Experimental Procedures

3.1.2. Synthesis

tert-Butyl-2-amino-5-(3-chloropropoxy)benzoate (2)

tert-Butyl-2-(6-bromohexanamido)-5-(3-chloropropoxy)benzoate (3)

tert-Butyl-2-(6-azidohexanamido)-5-(3-azidopropoxy)benzoate (4)

2-(6-Azidohexanamido)-5-(3-azidopropoxy)benzoic acid (5)

6-Azido-N-(4-(3-azidopropoxy)-2-(4-benzhydrylpiperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (6a)

6-Azido-N-(4-(3-azidopropoxy)-2-(4-(bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (6b)

6-Azido-N-(4-(3-azidopropoxy)-2-(4-phenylpiperidine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (6c)

6-Azido-N-(4-(3-azidopropoxy)-2-(4-((3a,7a-dihydrobenzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (6d)

6-Amino-N-(4-(3-aminopropoxy)-2-(4-benzhydrylpiperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (7a)

6-Amino-N-(4-(3-aminopropoxy)-2-(4-(bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (7b)

6-Amino-N-(4-(3-aminopropoxy)-2-(4-phenylpiperidine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (7c)

6-Amino-N-(4-(3-aminopropoxy)-2-(4-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-ylmethyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide (7d)

N-2(4-Benzhydrylpiperazine-1-carbonyl)-4-(3-guanidinopropoxy)phenyl-6-guanidinohexanamide dihydrochloride (8a)

N-2-(4-(Bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-(4-(3-guanidinopropoxy)phenyl)guanidinohexanamide dihydrochloride (8b)

6-Guanidino-N-(4-(3-guanidinopropoxy)-2-(4-phenylpiperidine-1-carbonyl)phenyl)hexanamide dihydrochloride (8c)

N-(2-(4-(Benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)methyl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-4-(3-guanidinopropoxy)phenyl-6-guanidinohexanamide dihydrochloride (8d)

3.2. Biology

3.2.1. Cav2.2 Radioligand Displacement Assay

3.2.2. Fluorescence Measurement of Calcium Responses

3.2.3. Patch Clamp Electrophysiology

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Campbell, J.N.; Meyer, R.A. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron 2006, 52, 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Butera, J.A. Current and emerging targets to treat neuropathic pain. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 2543–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.D. Neuropathic pain: Molecular complexity underlies continuing unmet medical need. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 2547–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.; Denyer, J.C. N-type calcium channel blockers in pain and stroke. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 1998, 8, 1237–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, B.; Asgian, J.; Termin, A.; Zimmermann, N. Small molecules targeting sodium and calcium channels for neuropathic pain. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Develop. 2009, 12, 543–561. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T.; Takahara, A. Recent updates of N-type calcium channel blockers with therapeutic potential for neuropathic pain and stroke. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Zamponi, G.W.; Feng, Z.P.; Zhang, L.; Pajouhesh, H.; Ding, Y.; Belardetti, F.; Pajouhesh, H.; Dolphin, D.; Mitscher, L.A.; Snutch, T.P. Scaffold-based design and synthesis of potent N-type calcium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 6467–6472. [Google Scholar]

- Pajouhesh, H.; Feng, Z.P.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, L.; Pajouhesh, H.; Morrison, J.L.; Belardetti, F.; Tringham, E.; Simonson, E.; Vanderah, T.W.; et al. Structure-activity relationships of diphenylpiperazine N-type calcium channel inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1378–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Pajouhesh, H.; Feng, Z.P.; Zhang, L.; Pajouhesh, H.; Jiang, X.; Hendricson, A.; Dong, H.; Tringham, E.; Ding, Y.; Vanderah, T.W.; et al. Structure-activity relationships of trimethoxybenzylpiperazine N-type calcium channel inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4153–4158. [Google Scholar]

- Zalicus. Available online: http://www.zalicus.com (accessed on 7 September 2012).

- Scott, V.E.; Vortherms, T.A.; Niforatos, W.; Swensen, A.M.; Neelands, T.; Milicic, I.; Banfor, P.N.; King, A.; Zhong, C.; Simler, G.; et al. A-1048400 is a novel, orally active, state-dependent neuronal calcium channel blocker that produces dose-dependent antinociception without altering hemodynamic function in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012, 83, 406–418. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, G.A.; Bhatia, P.; Vortherms, T.A.; Marsh, K.C.; Wetter, J.M.; Mack, H.; Scott, V.E.; Jarvis, M.F.; Stewart, A.O. Discovery of diphenyllactam derivatives as N-type calcium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 1716–1718. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, X.; Darczak, D.; Henry, R.F.; Vortherms, T.A.; Janis, R.; Namovic, M.; Donnelly-Roberts, D.; Kage, K.L.; Surowy, C.; Milicic, I.; et al. Synthesis and SAR of 4-aminocyclopentapyrrolidines as N-type Ca2+ channel blockers with analgesic activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 4128–4139. [Google Scholar]

- Abbadie, C.; McManus, O.B.; Sun, S.-Y.; Bugianesi, R.M.; Dai, G.; Haedo, R.J.; Herrington, J.B.; Kaczorowski, G.J.; Smith, M.M.; Swensen, A.M.; et al. Analgesic effects of a substituted N-triazoleoxindole (TROX-1), a state-dependent, voltage-gated calcium channel 2 blocker. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 2010, 334, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagarajan, S.; Chakravarty, P.K.; Park, M.; Zhou, B.; Herrington, J.B.; Ratliff, K.; Bugianesi, R.M.; Williams, B.; Haedo, R.J.; Swensen, A.M.; et al. A potent and selective indole N-type calcium channel (Ca(v)2.2) blocker for the treatment of pain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 869–873. [Google Scholar]

- Subasinghe, N.L.; Wall, M.J.; Winters, M.P.; Qin, N.; Lubin, M.L.; Finley, M.F.A.; Brandt, M.R.; Neeper, M.P.; Schneider, C.R.; Colburn, R.W.; et al. A novel series of pyrazolylpiperidine N-type calcium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 4080–4083. [Google Scholar]

- Olivera, B.; Teichert, R.W. Diversity of the neurotoxicConus peptides: a model for concerted pharmacological discovery. Mol. Interv. 2007, 7, 251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, R.J.; Dutertre, S.; Vetter, I.; Christie, M.J. Conus venom peptide pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012, 64, 259–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.J.; Callaghan, B.; Berecki, G. Analgesic conotoxins: block and G protein-coupled receptor modulation of N-type (Ca(v)2.2) calcium channels. Br. J. Pharm. 2012, 166, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pexton, T.; Moeller-Bertram, T.; Schilling, J.M.; Wallace, M.S. Targeting voltage-gated calcium channels for the treatment of neuropathic pain: a review of drug development. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2011, 20, 1277–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosov, A.; Goodchild, C.S.; Cooke, I. CNSB004 (Leconotide) causes antihyperalgesia without side effects when given intravenously: A comparison with ziconotide in a rat model of diabetic neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2010, 11, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolosov, A.; Aurini, L.; Williams, E.D.; Cooke, I.; Goodchild, C.S. Intravenous injection of leconotide, an omega conotoxin: Synergistic antihyperalgesic effects with morphine in a rat model of bone cancer pain. Pain Med. 2011, 12, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Forsyth, S.A.; Gable, R.W.; Norton, R.S.; Mulder, R.J. Design and synthesis of type-III mimetics of omega-conotoxin GVIA. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2001, 15, 1119–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Duggan, P.J.; Lok, Y.P. ω-conotoxins and approaches to their non-peptide mimetics. Aust. J. Chem. 2004, 57, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-X.; Cammidge, A.N.; Horwell, D.C. Dendroid peptide structural mimetics of omega-conotoxin MVIIA based on a 2(1H)-quinolinone core. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 5169–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzler, S.; Bikker, J.A.; Horwell, D.C. Synthesis of a non-peptide analogue of omega-conotoxin MVIIA. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998, 39, 7619–7622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzler, S.; Bikker, J.A.; Suman-Chauhan, N.; Horwell, D.C. Design and biological evaluation of non-peptide analogues of omega-conotoxin MVIIA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2000, 10, 345–347. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder, C.I.; Smythe, M.L.; Lewis, R.J. Development of small molecules that mimic the binding of omega-conotoxins at the N-type voltage-gated calcium channel. Mol. Divers. 2004, 8, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Duggan, P.J.; Forsyth, S.A.; Lewis, R.J.; Lok, Y.P.; Schroeder, C.I. Synthesis and biological evaluation of nonpeptidemimetics of omega-conotoxin GVIA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 4025–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, P.J.; Lewis, R.J.; Lok, Y.P.; Lumsden, N.G.; Tuck, K.L.; Yang, A. Low molecular weight non-peptide mimics of omega-conotoxin GVIA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2763–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Duggan, P.J.; Forsyth, S.A.; Lewis, R.J.; Lok, Y.P.; Schroeder, C.I.; Shepherd, N.E. Synthesis and biological evaluation of anthranilamide-based non-peptide mimetics of omega-conotoxin GIVA. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 7284–7292. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, A.; Baell, J.B.; Duggan, P.J.; Graham, J.E.; Lewis, R.J.; Lumsden, N.G.; Tranberg, C.E.; Tuck, K.L.; Yang, A. Omega-conotoxin GVIA mimetics based on an anthranilamide core: effect of variation in ammonium side chain lengths and incorporation of fluorine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 6659–6670. [Google Scholar]

- Lauri, G.; Bartlett, P.A. CAVEAT: A program to facilitate the design of organic molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1994, 8, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, R.J.; Murphy, K.M.; Reynolds, I.J.; Snyder, S.H. Antischizophrenic drugs of the diphenylbutylpiperidine type act as calcium channel antagonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 5122–5125. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M.; Koyakumaru, K.; Ohta, T.; Takaya, H. A simple and convenient synthesis of Alkyl Azides under mild conditions. Synthesis 1995, 4, 376–378. [Google Scholar]

- Shpiro, N.; Marquez, R. An improved synthesis of the potent MEK inhibitor PD184352. Synth. Commun. 2005, 35, 2265–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handlon, A.L.; Oppenheimer, N.J. Thiol reduction of 3′-azidothymidine to 3′-aminothymidine: kinetics and biomedical implications. Pharm. Res. 1988, 5, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernatowicz, M.S.; Wu, Y.; Matsueda, G.R. 1H-Pyrazole-1-carboxamidine hydrochloride an attractive reagent for guanylation of amines and its application to peptide synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 2497–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.J.; Nielsen, K.J.; Craik, D.J.; Loughnan, M.L.; Adams, D.A.; Sharpe, I.A.; Luchian, T.; Adams, D.J.; Bond, T.; Thomas, L.; et al. Novel omega-conotoxins from Conuscatus discriminate among neuronal calcium channel subtypes. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 35335–35344. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, J.A.; Snowman, A.M.; Biswas, A.; Olivera, B.M.; Snyder, S.H. omega-Conotoxin GVIA binding to a high-affinity receptor in the brain: Characterization, calcium sensitivity, and solubilization. J. Neurosci. 1988, 8, 3354–3359. [Google Scholar]

- Mould, J.; Yasuda, T.; Schroeder, C.I.; Beedle, A.M.; Doering, C.J.; Zamponi, G.W.; Adams, D.J.; Lewis, R.J. The alpha2delta auxiliary subunit reduces affinity of omega-conotoxins for recombinant N-type (Cav2.2) calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 34705–34714. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, H.L.; Vaughan, P.F.; Peers, C. Calcium channel currents in undifferentiated human neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y) cells: Actions and possible interactions of dihydropyridines and omega-conotoxin. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994, 6, 943–952. [Google Scholar]

- Reuveny, E.; Narahashi, T. Two types of high voltage-activated calcium channels in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res. 1993, 603, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, A.J.; Hammond, C.; Mason, W.T.; Henderson, G. Characterisation of the L- and N-type calcium channels in differentiated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells: calcium imaging and single channel recording. Mol. Brain Res. 1992, 13, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toselli, M.; Masetto, S.; Rossi, P.; Taglietti, V. Characterization of a Voltage-dependent Calcium Current in the Human Neuroblastoma Cell Line SH-SY5Y During Differentiation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1991, 3, 514–522. [Google Scholar]

- Pangborn, A.B.; Giardello, M.A.; Grubbs, R.H.; Rosen, R.K.; Timmers, F.J. Safe and Convenient Procedure for Solvent Purification. Organometallics 1996, 15, 1518–1520. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, G.; Haedo, R.J.; Warren, V.A.; Ratliff, K.S.; Bugianesi, R.M.; Rush, A.; Williams, M.E.; Herrington, J.; Smith, M.M.; McManus, O.B.; et al. A high-throughput assay for evaluating state dependence and subtype selectivity of Cav2 calcium channel inhibitors. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2008, 6, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.J.; Sturino, C. Managing the Liabilities Arising from Structural Alerts: A Safe Philosophy for Medicinal Chemists. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 3116–3135. [Google Scholar]

- Kalgutkar, A.S.; Gardner, I.; Obach, R.S.; Shaffer, C.L.; Callegari, E.; Henne, K.R.; Mutlib, A.E.; Dalvie, D.K.; Lee, J.S.; Nakai, Y.; et al. A comprehensive listing of bioactivation pathways of organic functional groups. Curr. Drug Metab. 2005, 6, 161–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, R.S.; Baell, J.B.; Angus, J.A. Calcium Channel Blocking Polypeptides: Structure, Function, and Molecular Mimicry. In Calcium Channel Pharmacology; McDonough, S.I., Ed.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 143–179. [Google Scholar]

- Samples Availability: Available from the authors.

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Tranberg, C.E.; Yang, A.; Vetter, I.; McArthur, J.R.; Baell, J.B.; Lewis, R.J.; Tuck, K.L.; Duggan, P.J. ω-Conotoxin GVIA Mimetics that Bind and Inhibit Neuronal Cav2.2 Ion Channels. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 2349-2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/md10102349

Tranberg CE, Yang A, Vetter I, McArthur JR, Baell JB, Lewis RJ, Tuck KL, Duggan PJ. ω-Conotoxin GVIA Mimetics that Bind and Inhibit Neuronal Cav2.2 Ion Channels. Marine Drugs. 2012; 10(10):2349-2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/md10102349

Chicago/Turabian StyleTranberg, Charlotte Elisabet, Aijun Yang, Irina Vetter, Jeffrey R. McArthur, Jonathan B. Baell, Richard J. Lewis, Kellie L. Tuck, and Peter J. Duggan. 2012. "ω-Conotoxin GVIA Mimetics that Bind and Inhibit Neuronal Cav2.2 Ion Channels" Marine Drugs 10, no. 10: 2349-2368. https://doi.org/10.3390/md10102349