Construction of a nrdA::luxCDABE Fusion and Its Use in Escherichia coli as a DNA Damage Biosensor

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

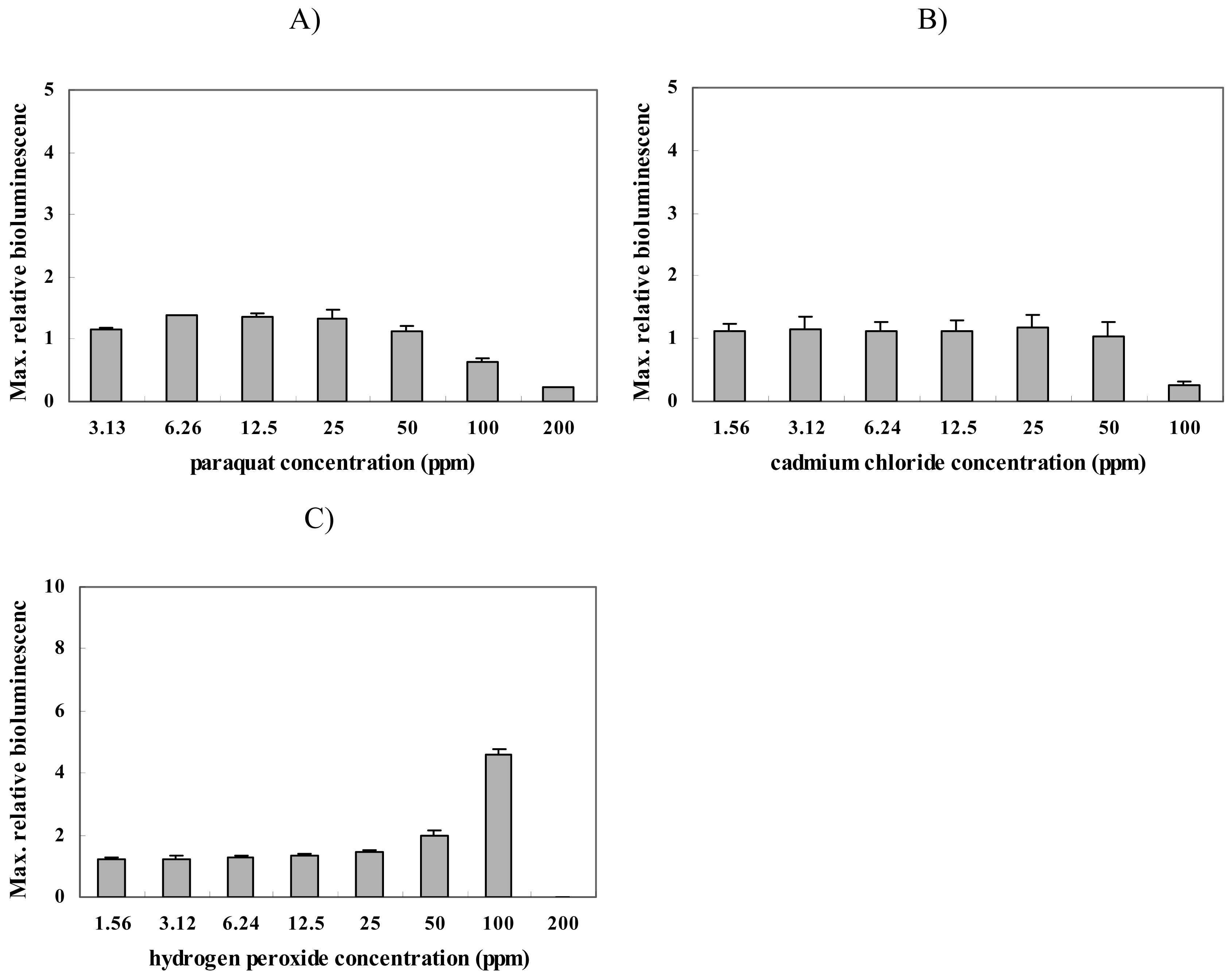

2.1. Response of strain BBTNrdA to DNA damaging chemicals

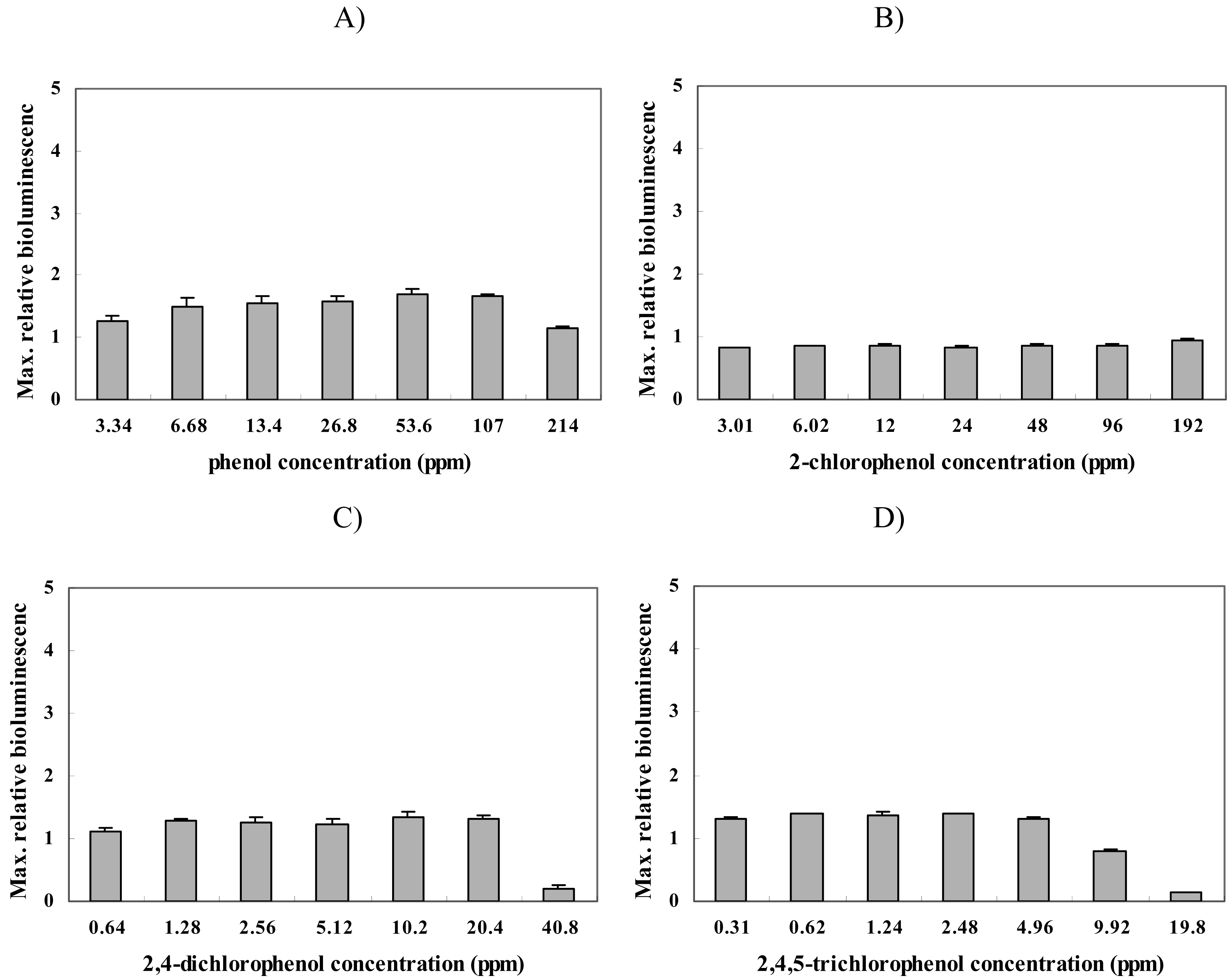

2.2. Response of strain BBTNrdA to other chemicals

3. Experimental Section

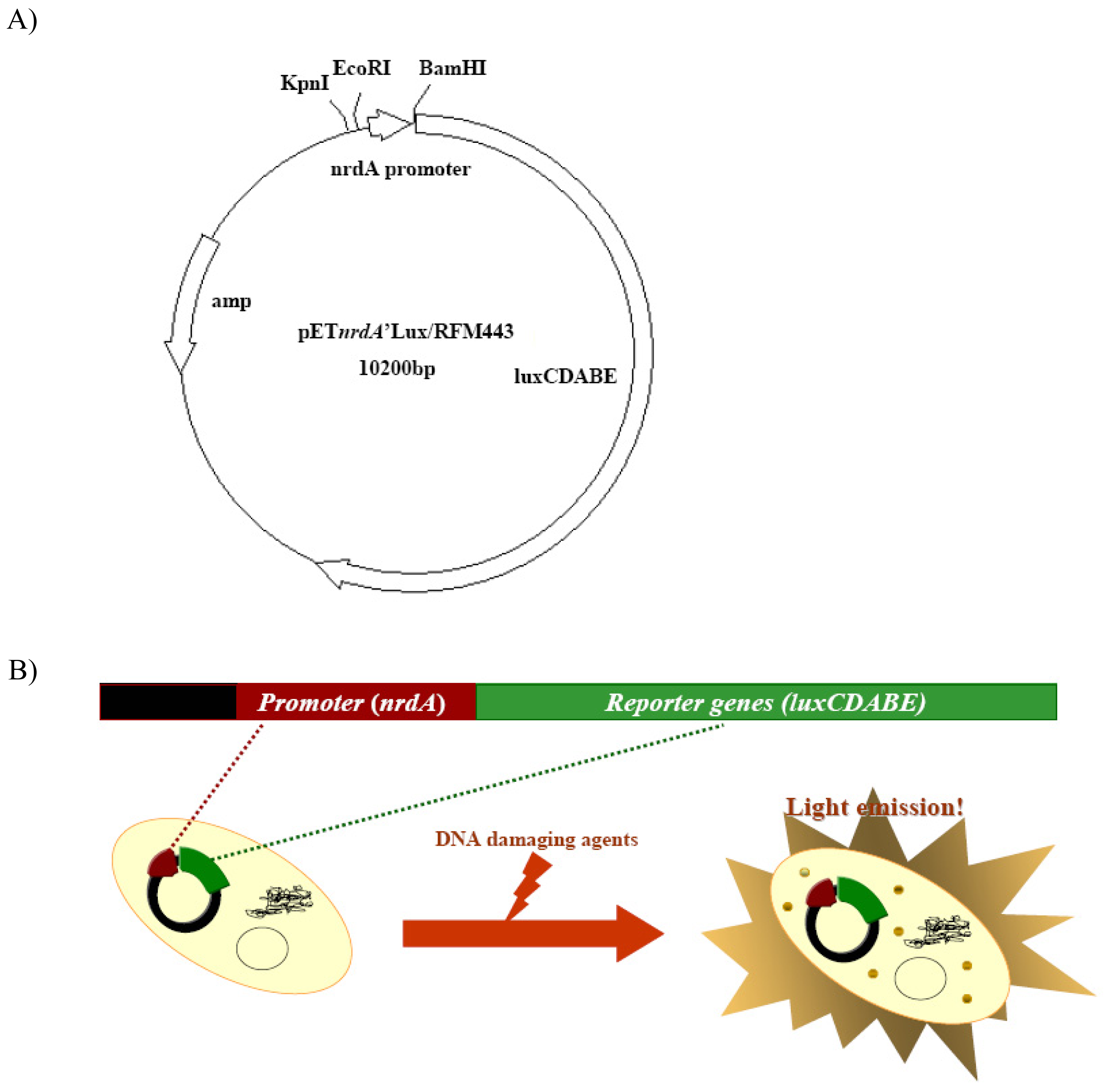

3.1. Construction of strain BBTNrdA

3.2. Culture Condition and Chemical Test Protocol

3.3. Chemicals

3.4. Data Analysis

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Ptitsyn, L. R.; Horneck, G.; Komova, O.; Kozubek, S.; Krasavin, E. A.; Bonev, M.; Rettberg, P. A Biosensor for Environmental Genotoxin Screening Based on an SOS lux Assay in Recombinant Escherichia coli Cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 4377–4384. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J. M.; Kim, B. C.; Gu, M. B. Characterization of gltA::luxCDABE fusion in Escherichia coli as a Toxicity Biosensor. Biotechnol. Bioprocess. Eng. 2006, 11, 16–521. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B. C.; Youn, C. H.; Ahn, J. M.; Gu, M. B. Screening of target-specific stress-responsive genes for the development of cell-based biosensors using a DNA microarray. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 8020–8026. [Google Scholar]

- Billard, P.; DuBow, M. S. Bioluminescence-based assays for detection and characterization of bacteria and chemicals in clinical laboratories. Clin Biochem. 1998, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, G. S; Williams, P. Lux genes and the applications of. bacterial bioluminescence. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1992, 138, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Morin, J. G.; Hastings, J. W. Energy transfer in a bioluminescent system. J. Cell. Physiol. 1971, 77, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Meighen, E. A. Molecular biology of bacterial bioluminescence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1991, 55, 123–142. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, M. B.; Mitchell, R. J.; Kim, B. C. Whole cell-based biosensors for environmental biomonitoring and application. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2004, 87, 269–305. [Google Scholar]

- Belkin, S. Microbial whole-cell sensing systems ofenvironmental pollutants. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2003, 6, 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Daunert, S.; Barrett, G.; Feliciano, J. S.; Shetty, R. S.; Shrestha, S.; Smith-Spencer, W. Genetically engineered whole-cell sensing systems: coupling biological recognition with reporter genes. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2705–2738. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.J.; Gu, M. B. An Escherichia coli biosensor capable of detecting both genotoxic and oxidative damage. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 64, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, A.; Hansen, L. H.; Sørensen, S. J. Construction of a ColD cda promoter-based SOS-green fluorescent protein whole-cell biosensor with higher sensitivity toward genotoxic compounds than constructs based on recA, umuDC, or sulA promoters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005, 71, 2338–2346. [Google Scholar]

- Baumstark-Khan, C.; Cioara, K.; Rettberg, P.; Horneck, G. Determination of geno- and cytotoxicity of groundwater and sediments using the recombinant SWITCH test. J Environ Sci Health. Part A. 2005, 40, 245–263. [Google Scholar]

- Rabbow, E.; Rettberg, P.; Baumstark-Khan, C.; Horneck, G. SOS-LUX- and LAC-FLUORO-TEST for the quantification of genotoxic and/or cytotoxic effects of heavy metal salts. Anal Chim Act. 2002, 456, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Lars, T. Physicochemical Characterization of Ribonucleoside Diphosphate Reductase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Che. 1973, 248, 4591–1601. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe, J. Ribonucleotide Reductases: Amazing and Confusing. J Biol Chem. 1990, 265, 5329–5332. [Google Scholar]

- Courcelle, J.; Khodursky, A.; Peter, B.; Brown, P.O. P.; Hanawalt, C. Comparative gene expression profiles following UV exposure in wild-type and SOS-deficient. Escherichia coli, Genetics. 2001, 158, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, S.; Sjoberg, B.; Karlstrom, O.; Hahne, S. Ribonucleoside Diphosphate Reductase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1977, 252, 6132–6138. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, E.; Jimenez-Sanchez, A.; Guzman, E. C. Defective Ribonucleoside Diphosphate Reductase Impairs Replication Fork Progression in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 3496–3501. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbe, J.; Krenitsky, T.; Ator, M. Mechanism of Ribonucleoside Diphosphate Reductase from Echerichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1983, 258, 1625–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, E.; Bolivar, F. The ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase gene (nrdA) of Escherichia coli carries a repetitive extragenicpalindromic (REP) sequence in its 3′ structural terminus. Mol. Microbiol. 1989, 3, 839–841. [Google Scholar]

- Min, J. H.; Gu, M. B. Acclimation and repair of DNA damage in recombinant bioluminescent Escherichia coli. J. Appl. Micorbiol. 2003, 95, 479–483. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, W. A.; Deitz, W. H.; Cook, T. M. Mechanism of Action of Nalidixic Acid on Escherichia coli. J. Bacterio. 1965, 89, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasz, M. Mitomycin C: small, fast and deadly (but very selective). Chemistry & Biology 1995, 2, 575–579. [Google Scholar]

- Min, J. H.; Kim, E. J.; LaRossa, R. A.; Gu, M. B. Distinct responses of a recA::luxCDABE Escherichia coli strain to direct and indirect DNA damaging agents. Mutat. Res. 1999, 442, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, D. J.; Gallus, M. S.; McKeown, R. C.; Downes, S.; McKelvey-Martin, V. J. Modification of the alkaline Comet assay to allow simultaneous evaluation of mitomycin C-induced DNA cross-link damage and repair of specific DNA sequences in RT4 cells. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2003, 2, 879–890. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Michael, D. T. Enhanced Resistance to Nitrosoguanidine Killing and Mutagenesis in a DNA Gyrase Mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1982, 151, 764–770. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M. K.; Kuwabara, Y.; Hara, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Tamai, Y. Antimutagenic effect of amino acids on the mutagenicity of N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2002, 66, 1400–1402. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, H.; Ichikawa-Ryo, H.; Kondo, S. Dose-rate dependence of mutagenesis by ultraviolet radiation and 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide in Escherichia coli. Jpn. J. Genet. 1983, 58, 283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Poot, M.; Gollahon, K. A.; Emond, M. J.; Silber, J. R.; Rabinovitch, P. S. Werner syndrome diploid fibroblasts are sensitive to 4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide and 8-methoxypsoralen: implications for the disease phenotype1. The FASEB Journal. 2002, 16, 757–758. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell., R. J.; Gu, M. B. Construction and characterization of novel dual stress-responsive bacterial biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2004, 19, 977–985. [Google Scholar]

- Min, J. H.; Gu, M. B. Adaptive Responses of Escherichia coli for Oxidative and Protein Damages Using Bioluminescence Reporter. J. Microbiol. Biotechn. 2004, 14, 466–469. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S. H.; Gu, M. B. Phenolic toxicitydetection and classification through the use of a recombinant bioluminescent Escherichia coli. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2001, 20, 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Drolet, M.; Phoenix, P.; Menzel, R.; Masse, E.; Liu, L. F.; Crouch, R. J. Overexpression of RNase H partially complements the growth defect of an Escherichia coli Δ topA mutant: R-loop formation is a major problem in the absence of DNA topoisomerase I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92, 3526–3530. [Google Scholar]

- Vandyk, T. K.; Rosson, R. A. Photorhabdus luminescens luxCDABE promoter probe vectors. Methods Mol. Biol. 1995, 102, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Chemicals | MDC (ppm) | MRC (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA damage | nalidixic acid | 2.5 | 10 |

| mitomycin C | 0.3125 | 80 | |

| 1-methyl-1-nitroso-N-methylguanidine | 0.1563 | 80 | |

| 4-nitroquinoline N-oxide | 2.5 | 20 | |

| Oxidative damage | paraquat | ND | ND |

| cadmium chloride | ND | ND | |

| hydrogen peroxide | 50 | 100 | |

| Phenol compounds | phenol | ND | ND |

| 2-chlorophenol | ND | ND | |

| 2,4-dichlorophenol | ND | ND | |

| 2,4,5-trichlorophenol | ND | ND |

© 2008 by MDPI Reproduction is permitted for noncommercial purposes.

Share and Cite

Hwang, E.T.; Ahn, J.-M.; Kim, B.C.; Gu, M.B. Construction of a nrdA::luxCDABE Fusion and Its Use in Escherichia coli as a DNA Damage Biosensor. Sensors 2008, 8, 1297-1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/s8021297

Hwang ET, Ahn J-M, Kim BC, Gu MB. Construction of a nrdA::luxCDABE Fusion and Its Use in Escherichia coli as a DNA Damage Biosensor. Sensors. 2008; 8(2):1297-1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/s8021297

Chicago/Turabian StyleHwang, Ee Taek, Joo- Myung Ahn, Byoung Chan Kim, and Man Bock Gu. 2008. "Construction of a nrdA::luxCDABE Fusion and Its Use in Escherichia coli as a DNA Damage Biosensor" Sensors 8, no. 2: 1297-1307. https://doi.org/10.3390/s8021297