Nanomaterials for the Selective Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide in Air

Abstract

:1. Introduction

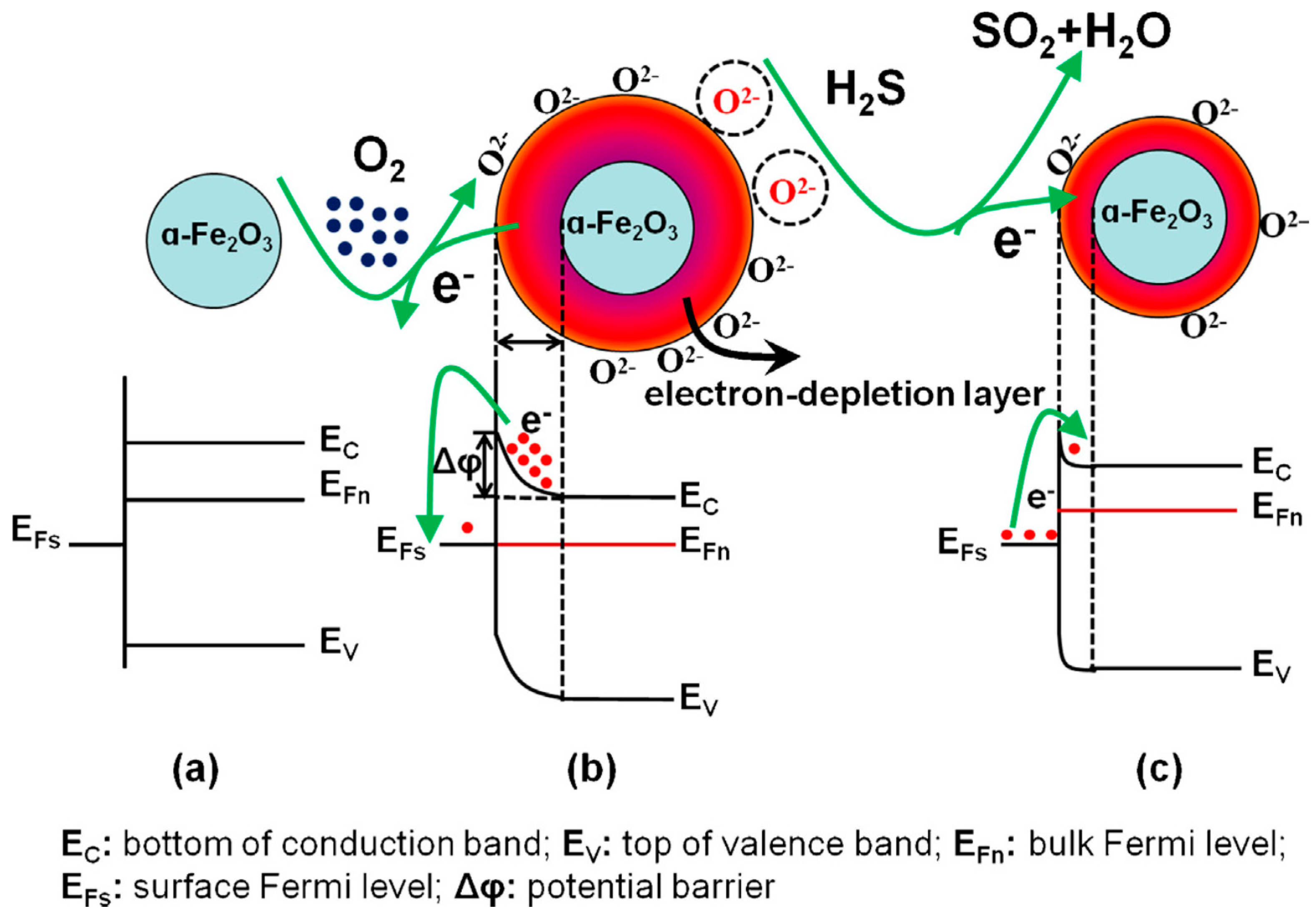

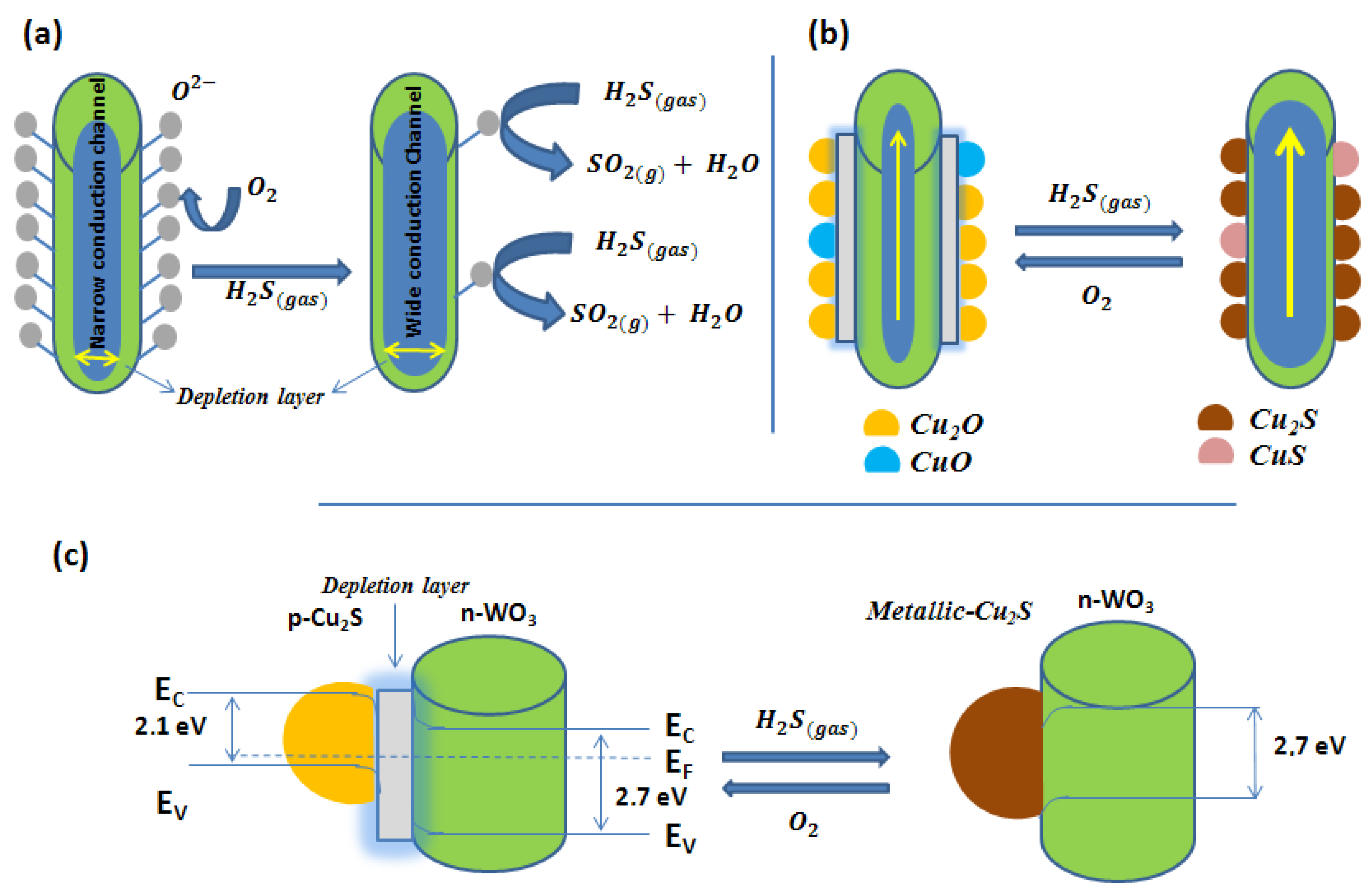

2. Metal Oxide Nanomaterials

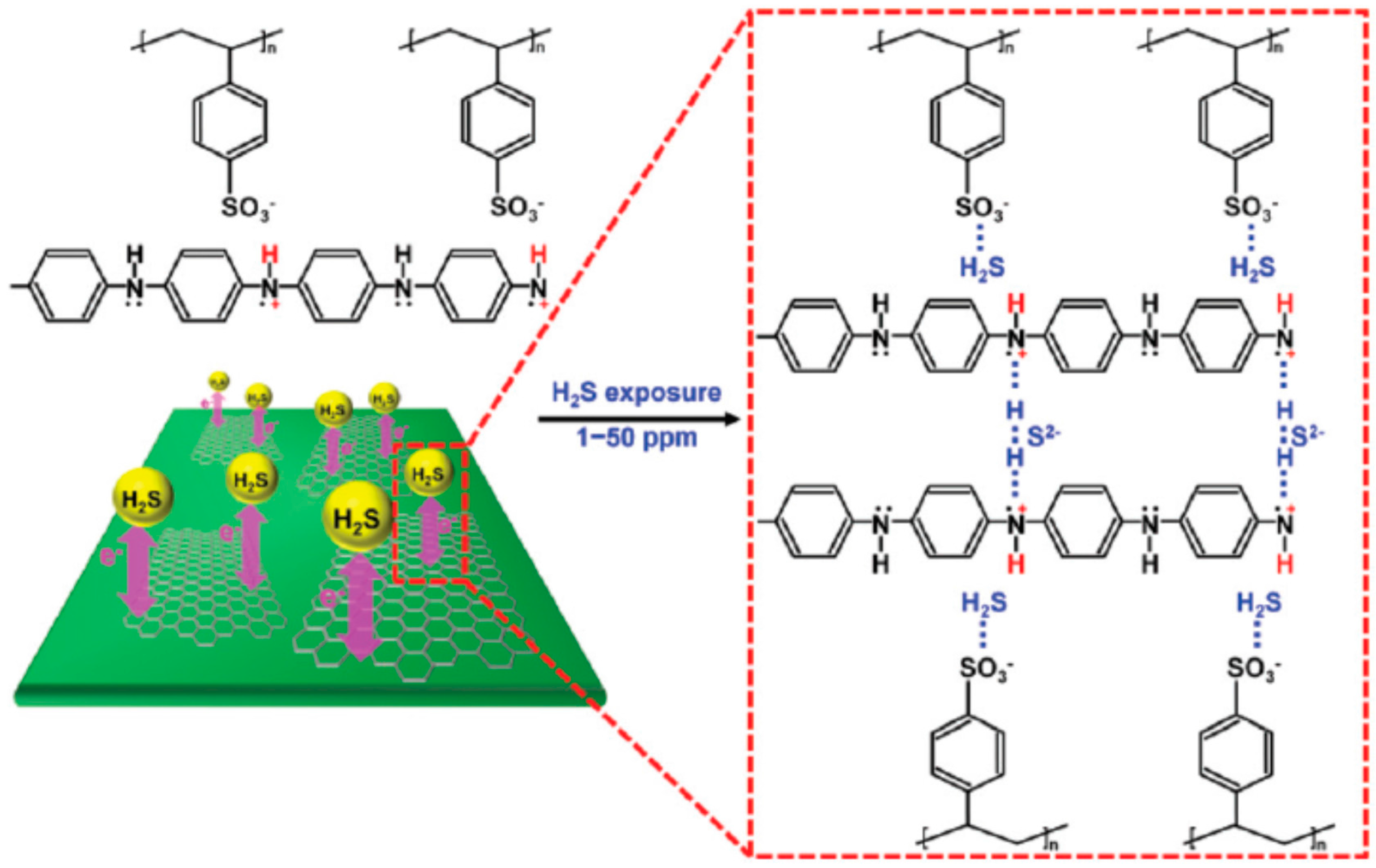

3. Functionalized Carbon Nanomaterials

4. Other Nanomaterials and Transduction Approaches

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration, USA, OSHA Standards: Hydrogen sulfide exposure. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/hydrogensulfide/standards.html (accessed on 23 January 2017).

- Kim, K.H.; Choi, Y.J.; Jeon, E.C.; Sunwoo, Y. Characterization of malodorous sulfur compounds in landfill gas. Atmos. Environ. 2005, 39, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Jeon, E.C.; Choi, Y.J.; Koo, Y.S. The emission characteristics and the related malodor intensities of gaseous reduced sulfur compounds (RSC) in a large industrial complex. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 4478–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; De Schryver, P.; De Gusseme, B.; De Muynck, W.; Boon, N.; Verstraete, W. Chemical and biological technologies for hydrogen sulfide emission control in sewer systems: A review. Water Res. 2008, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Concise International Chemical Assessment Document 53, Hydrogen sulfide: Human health aspects. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003. Available online: http://www.who.int/ipcs/publications/cicad/en/cicad53.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2017).

- US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA). Toxicological Review of Hydrogen Sulfide. Washington, DC, USA, 2003. Available online: https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPURL.cgi?Dockey=P1006BZD.TXT (accessed on 23 January 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Shanthi, K.; Balasubramanian, N. A Simple Spectrophotometric Method for the Determination of Hydrogen Sulfide Based on Schiff’s Reaction. Microchem. J. 1996, 53, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Kim, K.H.; Tang, K.T. A review of sensor-based methods for monitoring hydrogen sulfide. Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 32, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membrapor, AG, Switzerland: Electrochemical gas sensors for detecting H2S. Available online: http://www.membrapor.ch/ (accessed on 23 January 2017).

- Alphasense, Ltd, United Kingdom.: Alphasense hydrogen sulphide gas sensors. Available online: http://www.alphasense.com/index.php/products/hydrogen-sulfide-safety/ (accessed on 23 January 2017).

- Davydow, A.; Chuang, K.T.; Sanger, A.R. Mechanism of H2S oxidation by ferric oxide and hydroxide surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 4745–4752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, X. A highly selective chemiluminescent H2S sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2004, 102, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Han, B.; Ding, K.; An, G. Large-scale production of self-assembled SnO2 nanospheres and their application in high-performance chemiluminescence sensors for hydrogen sulfide gas. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 1791–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Mei, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, T.; Xu, Z.; Duan, X.; Zheng, W. α-Fe2O3 nanochains: ammonium acetate-based ionothermal synthesis and ultrasensitive sensors for low-ppm-level H2S gas. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lia, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, W.; Kuang, Z.; Ao, D.; Liu, W.; Fu, Y. A fast response and recovery H2S gas sensor based on α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles with ppb level detection limit. J. Hazard. Mat. 2015, 300, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, B.; Kong, F.; Wang, D.; Wu, S.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S. H2S sensing characteristics of Pt-doped α-Fe2O3 thick film sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 125, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizsei, J.; Sipila, P.; Lantto, V. Structural studies of sputtered noble metal catalysts on oxide surfaces. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1998, 47, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishampayan, M.V.; Deshmukh, R.G.; Walke, P.; Mulla, I.S. Fe-doped SnO2 nanomaterial: A low temperature hydrogen sulfide gas sensor. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2008, 109, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Gao, X.M.; Di, X.-P.; Ouyang, Q.Y.; Gao, P.; Qi, L.H.; Li, C.Y.; Zhu, C.L. Porous Iron Molybdate Nanorods: In situ Diffusion Synthesis and Low-Temperature H2S Gas Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 3267–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.L.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Z.M.; Yang, H.F.; Shen, G.L.; Yu, R.Q. Hydrogen sulfide sensing properties of NiFe2O4 nanopowder doped with noble metals. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2004, 102, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapse, V.D.; Ghosh, S.A.; Raghuwanshi, F.C.; Kapse, S.D. Nanocrystalline spinel Ni0.6Zn0.4Fe2O4: A novel material for H2S sensing. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2009, 113, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, I.; Arbiol, J.; Dezanneau, G.; Cornet, A.; Morante, J.R. Crystalline structure, defects and gas sensor response to NO2 and H2S of tungsten trioxide nanopowders. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2003, 93, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankova, M.; Vilanova, X.; Llobet, E.; Calderer, J.; Vinaixa, M.; Gracia, I.; Cane, C.; Correig, X. On-line monitoring of CO2 quality using doped WO3 thin film sensor. Thin Solid Films 2006, 500, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickelson, W.; Sussman, A.; Zettl, A. Low-power, fast, selective nanoparticle-based hydrogen sulfide gas sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 173110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruefu, V.; Wisitsoraat, A.; Tuantranont, A.; Phanichphant, S. Ultra-sensitive H2S sensors based on hydrothermal/impregnation-made Ru-functionalized WO3 nanorods. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 215, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chu, X.; Wu, M. Detection of H2S down to ppb levels at room temperature using sensors based on ZnO nanorods. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2006, 113, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yu, K.; Li, Q.; Zhu, Z.Q.; Wan, Q. Room-temperature high-sensitivity H2S gas sensor based on dendritic ZnO nanostructures with macroscale in appearance. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 104305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badadhe, S.S.; Mulla, I.S. H2S gas sensitive indium-doped ZnO thin films: Preparation and characterization. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 143, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xua, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, J. Hydrothermal synthesis of In2O3 for detecting H2S in air. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2006, 115, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Niu, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, N.; Shen, H.; Liu, W.; Sun, K.; Fu, Y.Q.; Wang, Z. Hydrothermally synthesized CeO2 nanowires for H2S sensing at room temperature. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 682, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, C.; Lee, D.W. Perovskite hexagonal YMnO3 nanopowder as p-type semiconductor gas sensor for H2S detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 221, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llobet, E.; Molas, G.; Molinàs, P.; Calderer, J.; Vilanova, X.; Brezmes, J.; Sueiras, J.E.; Correig, X. Fabrication of highly selective tungsten oxide ammonia sensors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000, 147, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Luo, W.; Qin, N.; Dong, J.; Wei, J.; Li, W.; Feng, S.; Chen, J.; Xu, J.; Elzatahry, A.A.; Es-Saheb, M.-H.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, D. Highly Ordered Mesoporous Tungsten Oxides with a Large Pore Size and Crystalline Framework for H2S Sensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 9035–9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roso, S.; Bittencourt, C.; Umek, P.; González, O.; Güell, F.; Urakawa, A.; Llobet, E. Synthesis of single crystalline In2O3 octahedra for the selective detection of NO2 and H2 at trace levels. J. Mat. Chem. C 2016, 4, 9418–9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manorama, S.; Devi, G.S.; Rao, V.J. Hydrogen sulfide sensor based on tin oxide deposited by spray pyrolysis and microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1994, 64, 3163–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, J.; Shimanoe, K.; Yamada, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Miura, N.; Yamazoe, N. Dilute hydrogen sulfide sensing properties of CuO–SnO2 thin film prepared by low-pressure evaporation method. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1998, 49, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliev, R.B.; Rumyantseva, M.N.; Yakovlev, N.V.; Gaskov, A.M. CuO:SnO2 thin film heterostructures as chemical sensors to H2S. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1998, 50, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, A.; Kumar, R.; Bhatti, S.S. CuO-doped SnO2 thin films as hydrogen sulfide gas sensor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2003, 82, 4388–4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhuri, A.; Gupta, V.; Sreenivas, K.; Kumar, R.; Mozumdar, S.; Patanjali, P.K. Response speed of SnO2-based H2S gas sensors with CuO nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 84, 1180–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Li, Y. High sensitivity of CuO modified SnO2 nanoribbons to H2S at room temperature. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2005, 105, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.; Singh, N.K.; Mishra, V.N.; Dwivedi, R. Selective detection of hydrogen sulfide using copper oxide-doped tin oxide based thick film sensor array. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2013, 142, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Lin, Z.D.; Li, N.; Fu, P.; Wang, X.H. Preparation and H2S Gas-Sensing Performances of Coral-Like SnO2–CuO Nanocomposite. Acta Metall. Sin. 2015, 28, 1190–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Zhang, M.; Zou, G. Resonant tunneling modulation in quasi-2D Cu2O/SnO2 p-n horizontal multi-layer heterostructure for room temperature H2S sensor application. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Duan, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.; Cai, W. CuO–ZnO Micro/Nanoporous Array-Film-Based Chemosensors: New Sensing Properties to H2S. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 6040–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuong, N.M.; Chinh, N.D.; Huy, B.T.; Lee, Y.I. CuO-Decorated ZnO Hierarchical Nanostructures as Efficient and Established Sensing Materials for H2S Gas Sensors. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagh, M.S.; Patil, L.A.; Seth, T.; Amalnerkar, D.P. Surface cupricated SnO2–ZnO thick films as a H2S gas sensor. Mat. Chem. Phys. 2004, 84, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annanouch, F.E.; Haddi, Z.; Vallejos, S.; Umek, P.; Guttmann, P.; Bittencourt, C.; Llobet, E. Aerosol-Assisted CVD-Grown WO3 Nanoneedles Decorated with Copper Oxide Nanoparticles for the Selective and Humidity-Resilient Detection of H2S. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6842–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, A.; Luo, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, J.; Qin, Y. CuO Nanosheets for Sensitive and Selective Determination of H2S with High Recovery Ability. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 19214–19219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennemann, J.; Kohl, C.D.; Smarsly, B.M.; Metelmann, H.; Rohnke, M.; Janek, J.; Reppin, D.; Meyer, B.K.; Russ, S.; Wagner, T. Copper oxide based H2S dosimeters—Modeling of percolation and diffusion processes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 217, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneer, J.; Knobelspies, S.; Bierer, B.; Wöllenstein, J.; Palzer, S. New method to selectively determine hydrogen sulfide concentrations using CuO layers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 222, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspera, E.D.; Guglielmi, M.; Agnoli, S.; Granozzi, G.; Post, M.L.; Bello, V.; Mattei, G.; Martucci, A. Au Nanoparticles in Nanocrystalline TiO2-NiO Films for SPR-Based, Selective H2S Gas Sensing. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 3407–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, R.; Mishra, S.K.; Gupta, B.D. Surface plasmon resonance-based fiber optic hydrogen sulphide gas sensor utilizing Cu–ZnO thin films. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 11868–11874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.K.; Rani, S.; Gupta, B.D. Surface plasmon resonance based fiber optic hydrogen sulphide gas sensor utilizing nickel oxide doped ITO thin film. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 195, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, S.P.; Mishra, S.K.; Gupta, B.D. Fiber optic hydrogen sulfide gas sensors utilizing ZnO thin film/ZnOnanoparticles: A comparison of surface plasmon resonance and lossy mode resonance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 218, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usha, S.P.; Mishra, S.K.; Gupta, B.D. Zinc oxide thin film/nanorods based lossy mode resonance hydrogen sulphide gas sensor. Mater. Res. Express 2015, 2, 095003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, D.W.H.; Tok, A.I.Y.; Palaniappan, A.; Nopphawan, A.P.; Lohani, A.; Mhaisalkar, S.G. Selective sensing of hydrogen sulphide using silver nanoparticle decorated carbon nanotubes. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2009, 138, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubeen, S.; Zhang, T.; Chartuprayoon, N.; Rheem, Y.; Mulchandani, A.; Myung, N.V.; Deshusses, M.A. Sensitive Detection of H2S Using Gold Nanoparticle Decorated Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanolli, Z.; Leghrib, R.; Felten, A.; Pireaux, J.J.; Llobet, E.; Charlier, J.C. Gas Sensing with Au-Decorated Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 4592–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.; Vuong, N.M.; Lee, D.; Kim, D.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.; Hong, S.K.; Yoon, S.G. Co3O4–SWCNT composites for H2S gas sensor application. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 222, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, M.; Sheikhi, M.H. Surface acoustic wave based H2S gas sensors incorporating sensitive layers of single wall carbon nanotubes decorated with Cu nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 198, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, N.; Hussain, S.; Das, S.; Bhunia, R.; Bhar, R.; Pal, A.K. H2S Gas Sensor Based on Nanocrystalline Copper/DLC Composite Films. Plasmonics 2015, 10, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Shen, F.; Tian, X.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T.; Chen, W. Stable Cu2O nanocrystals grown on functionalized graphene sheets and room temperature H2S gas sensing with ultrahigh sensitivity. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 1564–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MalekAlaie, M.; Jahangiri, M.; Rashidi, A.M.; HaghighiAsl, A.; Izadi, N. Selective hydrogen sulfide (H2S) sensors based on molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) nanoparticle decorated reduced graphene oxide. Mat. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 2015, 38, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Lee, J.S.; Jun, J.; Kim, S.G.; Jang, J. Fabrication of water-dispersible and highly conductive PSS-doped PANI/graphene nanocomposites using a high-molecular weight PSS dopant and their application in H2S detection. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 15181–15195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaie, M.M.; Jahangiri, M.; Rashidi, A.M.; Asl, A.H.; Izadi, N. A novel selective H2S sensor using dodecylamine and ethylenediamine functionalized graphene oxide. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 29, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Kumar, M.; Garg, R.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, D. Amide Functionalized Graphene Oxide Thin Films for Hydrogen Sulfide Gas Sensing Applications. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 2929–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, G.; Taia, H.; Sunb, P.; Zhang, B. Copper phthalocyanine thin film transistors for hydrogen sulfide detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 176, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.A.; Mohammed, K.A. Gas sensitivity of some metal phthalocyanines. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 1998, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Brunet, J.; Varenne, C.; Ndiaye, A.; Pauly, A. Phthalocyanines based QCM sensors for aromatic hydrocarbons monitoring: Role of metal atoms and substituents on response to toluene. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 230, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Zhang, K.; Sun, J.; Zhang, D.; Luo, R.; Li, D.; Liu, C. Polythiophene-WO3 hybrid architectures for low-temperature, H2S detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 197, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, M.; Shao, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Cao, H.; Ma, W.; Tang, J. Enhancement of hydrogen sulfide gas sensing of PbS colloidal quantum dots by remote doping through ligand exchange. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 212, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, D.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Z.; He, J.; Hub, L.; Xia, Z.; Tang, J.; Liu, H. Resistive gas sensors based on colloidal quantum dot (CQD) solids for hydrogen sulfide detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 217, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Song, H.; Lv, Y. Novel metal-organic frameworks-based hydrogen sulfide cataluminescence sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 220, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobek, M.; Kim, J.H.; Bechelany, M.; Vallicari, C.; Julbe, A.; Kim, S.S. MOF-Based Membrane Encapsulated ZnO Nanowires for Enhanced Gas Sensor Selectivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8323–8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Bhalla, V.; Kumar, M. Recent developments of fluorescent probes for the detection of gasotransmitters (NO, CO and H2S). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 2335–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, Z.; Ren, W.; Ai, H. Reaction-Based Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Hydrogen Sulfide Sensors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9589–9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarkar, S.S.; Desai, A.V.; Ghosh, S.K. A Nitro-Functionalized Metal–Organic Framework as a Reaction-Based Fluorescence Turn-On Probe for Rapid and Selective H2S Detection. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 9994–9997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coles, G.S.V.; Williams, G.; Smith, B. The effect of oxygen partial pressure on the response of tin (IV) oxide based gas sensors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 1991, 24, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loloee, R.; Chorpening, B.; Beer, S.; Ghosh, R.N. Hydrogen monitoring for power plant applications using SiC sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2008, 129, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Xie, S.; Wu, N.; Gou, Y.; Han, C.; Shi, Q.; Fang, D. Vertical SnO2 nanosheet-SiC nanofibers with hierarchical architecture for high-performance gas sensors. J. Mat. Chem. C 2016, 4, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiardo, A.; Bellutti, P.; Fabbri, B.; Gherardi, S.; Giberti, A.; Guidi, V.; Landini, N.; Malagù, C.; Pepponi, G.; Valt, M.; et al. Chemoresistive Gas Sensor based on SiC Thick Film: Possible Distinctive Sensing Properties between H2S and SO2. Proceedoa Eng. 2016, 168, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nanomaterial | Transduction Scheme | Operating Temperature | Response to H2S | Range and LOD | Response Time | Recovery Time | Selectivity (Not Affected by, Unless Otherwise Indicated) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Fe2O3 film | Chemi luminescence | 320 °C | 1827 (100 ppm) 1 | 8–2000 ppm/3 ppm | 15 s | 120 s | Ethanol, hexane, cyclohexane, ethylene, hydrogen, o-dichlorobenzene, carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, ammonia, thiophene, sulfur dioxide, dimethyl sulfur. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [12] |

| SnO2 nanospheres | Chemi luminescence | 160 °C | 2000 (5 ppm) 1 | NA 5 | 4 s | 20 s | Carbon monoxide, hydrogen, nitrogen dioxide. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [13] |

| α-Fe2O3 nanochains | Chemo resistor | 285 °C | 20 (100 ppm) 2 | 1–100 ppm/1 ppm | 8.6 s | 66 s | NA 5 | [14] |

| α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles | Chemo resistor | 300 °C | 5 (10 ppm) 2 | 0.05–100 ppm/50 ppb | 30 s | 5 s | NA 5 | [15] |

| Pt-doped α-Fe2O3 film | Chemo resistor | 160 °C | 330 (100 ppm) 2 | 10–1000 ppm/units of ppm | >1 min | >1 min | Ethane, carbon monoxide, significant cross-sensitivity to ethanol and ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [16] |

| Fe-doped SnO2 | Chemo resistor | 150 °C | 90 (100 ppm) 2 | 10–250 ppm/10 ppm | Few s | 100 s | Carbon monoxide, liquefied petroleum gas, significant cross-sensitivity to ethanol. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [18] |

| Fe2(MoO4)3 nanorods | Chemo resistor | 80 °C | 18 (50 ppm) 2 | 1–50 ppm/1 ppm | 30 s | 150 s | NA 5 | [19] |

| NiFe2O4 | Chemo resistor | 300 °C | 35.8 (5 ppm) 2 | 5–200 ppm/1 ppm | 15 s | 35 s | Liquefied petroleum gas, methane, carbon monoxide, butane, significant cross-sensitivity to hydrogen. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [20] |

| Ni0.6Zn0.4Fe2O4 | Chemo resistor | 225 °C | 0.8 (50 ppm) 3 | NA 5 | 10 s | 95 s | Significant cross-sensitivity to ethanol, liquefied petroleum gas, ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [21] |

| Pure and metal loaded WO3 | Chemo resistor | 200 °C to 350 °C | 25–190 (10 ppm) 2 | 0.2–200 ppm/200 ppb | 1 s | 11 min | Significant cross-sensitivity to ammonia, nitrogen dioxide and ambient moisture. | [22,23,24,25] |

| Mesoporous WO3 | Chemo resistor | 250 °C | 325 (100 ppm) 2 | 0.25–200 ppm/250 ppb | 2 s | 38 s | Hydrogen, benzene, with some cross-sensitivity to methanol, ethanol, acetone, ammonia, and acetaldehyde. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [33] |

| Pure or In doped ZnO | Chemo resistor | RT 4 to 250 °C | 17 to 90 (100 ppm) 2 | 0.5 to 100 ppm/500 ppb | >20 min (RT); 2 s (250 °C) | >20 min (RT); 4 min (250 °C) | High cross-sensitivity to ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [26,27,28] |

| ZnO nanoparticles | Shift of SPR peak | RT 4 | 0.71 nm/ppm 6 | 10 to 100 ppm/NA 5 | 1 min | 1 min | Hydrogen, methane, ammonia, chlorine. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [54] |

| ZnO nanorods | Lossy mode resonance | RT 4 | 0.8 nm/ppm 6 | 10 to 100 ppm/NA 5 | NA 5 | NA 5 | Hydrogen, methane, ammonia, chlorine. Effect of ambient moisture not available. Response saturates at 60 ppm of H2S. | [55] |

| In2O3 | Chemo resistor | 270 °C | 120 (50 ppm) 2 | NA 5 | NA 5 | NA 5 | Hydrogen, ammonia, toluene, benzene, carbon monoxide, methane. Significant cross-sensitivity to liquefied petroleum gas, formaldehyde, and ethanol. Important cross-sensitivity to nitrogen dioxide. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [29,34] |

| CeO2 | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | 2 (100 ppm) 2 | 0.1 to 100 ppm/100 ppb | 20 s | 200 s | Hydrogen, with some cross-sensitivity to ethanol and ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [30] |

| YMnO3 | Chemo resistor | 100 °C | 90 (500 ppm) 2 | 20 to 100 ppm/NA 5 | 6 s | 6 s | Significant cross-sensitivity to liquefied petroleum gas, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen. Effect of ambient moisture not available. Response saturates for H2S concentrations higher than 100 ppm. | [31] |

| CuO-SnO2 | Chemo resistor | 200 °C | 0.88 (100 ppm) 3 | 100 to 500 ppm/NA 5 | 60 s | 40 s | NA 5. Response saturates for H2S concentrations higher than 300 ppm. | [35] |

| CuO-SnO2 | Chemo resistor | 300 °C | 88 (2 ppm) 2 | 20 to 1000 ppb/20 ppb | 10 min | 10 min | NA 5 | [36] |

| CuO-SnO2 | Chemo resistor | 160 °C | 250 (100 ppm) 2 | 25 to 300 ppm/NA 5 | 10 min | NA 5 | NA 5 | [37] |

| CuO-SnO2 | Chemo resistor | 140 °C | 106 (10 ppm) 2 | 10 to 160 ppm/NA 5 | 2 min | >20 min | NA 5 | [38] |

| CuO-SnO2 | Chemo resistor | 150 °C | 2000 (20 ppm) 2 | NA 5 | 14 s | 21 s | NA 5 | [39] |

| CuO-SnO2 nanoribbons | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | 1.8 × 104 (3 ppm) 2 | NA 5 | 15 s | >20 min | NA 5 | [40] |

| CuO-SnO2 | Chemo resistor | 150 °C | 0.81 (1000 ppm) 3 | 200–2500 ppm/tens of ppm | 53 s | 83 s | Hydrogen, carbon monoxide, liquefied petroleum gas, sulfur dioxide. Effect of ambient moisture not available. Response saturates for H2S concentrations higher than 1500 ppm. | [41] |

| CuO-SnO2 coral-like | Chemo resistor | 100 °C | 4173 (10 ppm) 2 | 0.1–10 ppm/20 ppb | 10 s | >30 min | Ethanol, formaldehyde. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [42] |

| Cu2O-SnO2 | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | 0.6 (100 ppm) 3 | 5–150 ppm/1 ppm | >1 min | >1 min | Toluene. Significant cross-sensitivity to hydrogen liquefied petroleum gas, nitric oxide, ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [43] |

| CuO-ZnO | Chemo resistor | 225 °C | 380 (10 ppm) 2 | 0.1–20 ppm/100 ppb | 10 s | 200 s | Ethanol, acetone, hydrogen, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, methane, acetaldehyde. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [44] |

| CuO-ZnO | Chemo resistor | 200 °C | 83.5 (5 ppm) 2 | 5–100 ppm/1 ppm | 572 s | 65 s | Carbon monoxide, ammonia, hydrogen, methane. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [45] |

| Cu-ZnO | Shift of SPR peak | RT 4 | 0.2 nm/ppm 6 | 10–100 ppm/NA 5 | 1 min | 1 min | NA 5 | [52] |

| Cu-SnO2-ZnO | Chemo resistor | 150 °C | 6.4 × 104 * | NA 5 | NA 5 | NA 5 | Liquefied petroleum gas, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, methane. Significant cross-sensitivity to carbon monoxide. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [46] |

| Copper oxides-WO3 | Chemo resistor | 390 °C | 26 (5 ppm) 2 | 0.3–5 ppm/100 ppb | 2 s | 684 s | Hydrogen, carbon monoxide, ammonia, benzene, nitrogen dioxide. Resilient to changes in the background humidity. | [47] |

| CuO nanosheets | Chemo resistor | 100 °C | 320 (1 ppm) 2 | 30–1200 ppb/20 ppb | 10 s | 10 s | Ammonia, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, hydrogen. Strong cross-sensitivity to ambient moisture. | [48] |

| CuO | Chemo resistor | Switching 150–450 °C | 1000 (5 ppm) 2 | NA 5 | <1 min | <1 min | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, ammonia. Slightly affected by changes in ambient moisture. | [50] |

| Au-TiO2-NiO | Absorbance change | 350 °C | 0.97 (100 ppm) 7 | 2–100 ppm/NA 5 | 1 min | 7 min | Carbon monoxide, hydrogen. Effect of ambient moisture not available. Response signal saturates for H2S concentrations higher than 10 ppm. | [51] |

| Ag-NiO-ITO | Shift of SPR peak | RT 4 | 1 nm/ppm 6 | 10–100 ppm/NA 5 | NA 5 | NA 5 | Hydrogen, ammonia, chlorine, carbon monoxide. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [53] |

| Ag-SWCNT | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | NA 5 | NA 5 | NA 5 | NA 5 | Cross-sensitivity to ammonia and nitric oxide. Effect of ambient moisture not available. Unstable response. Lack of baseline recovery. | [56] |

| Au-SWCNT | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | 0.23 (1 ppm) 3 | 20–1000 ppb/20 ppb | 5 min | >20 min | NA 5. Response saturates at 250 ppb of H2S. | [57] |

| Co3O4–SWCNT | Chemo resistor | 250 °C | 5 (100 ppm) 3 | 10–150 ppm/units of ppm | 2 min | 10 min | Ammonia, methane, hydrogen. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [59] |

| Cu-MWCNT | SAW | 150 °C | 240 kHz (100 ppm) 8 | 5–150 ppm/units of ppm | 7 s | 9 s | Hydrogen, ethanol, acetone. Ambient moisture affects the response (20% decrease in response at 150 °C). | [60] |

| Cu-Diamond Like Carbon | Shift of SPR peak | RT 4 | NA 5 | NA 5 | 1 min | NA 5 | NA 5 | [61] |

| Cu2O-Graphene | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | 0.35 (100 ppb) 3 | 5–100 ppb/1 ppb | 2 min | 10 min | Hydrogen, methane, ammonia. Significant cross-sensitivity to ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [62] |

| MoO3–rGO | Chemo resistor | 160 °C | 4120 (50 ppm) 2 | 50–500 ppm/50 ppm | 1 min | 2 min | Ethanol, nitric oxide, carbon monoxide. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [63] |

| PSS-doped PANI/graphene | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | 0.79 (50 ppm) 3 | 1–50 ppm/1 ppm | 5 min | >20 min | Ethanol. Significant cross-sensitivity to ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [64] |

| DDA-GO or EDA-GO or AMIDE-GO | Chemo resistor | RT 4 | 160 (50 ppm) 2 | 50–500 ppm/50 ppm | 1 min | 3 min | Carbon monoxide, nitric oxide. Significant cross-sensitivity to ethanol. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [65,66] |

| Cu-Phthalo cynanine | ChemFET | RT 4 | 0.605 (200 ppm) 9 | 100–500 ppm/NA 3 | 89 s | 290 s | Methane, hydrogen, carbon monoxide. Significant cross-sensitivity to ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. Poor recovery of the baseline. | [67] |

| Polytiophene-WO3 | Chemo resistor | 70 °C | 12 (100 ppm) 2 | 5–200 ppm/3 ppm | 10 s | 5 s | Methanol, ethanol, acetone, ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [70] |

| Colloidal PbS QDs | Chemo resistor | 135 °C | 4218 (50 ppm) 2 | 5–100 ppm/6 ppb | 23 s | 171 s | Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, ammonia. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [71,72] |

| MOFs | Chemi luminescence | 250 °C | 7500 (16 ppm) 1 | 6–16 ppm/1 ppm | 1 s | 5 s | Methanol, ethanol, propanol, butanol, isobutanol, acetone, formaldehyde, toluene, chloroform. Effect of ambient moisture not available. | [73] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Llobet, E.; Brunet, J.; Pauly, A.; Ndiaye, A.; Varenne, C. Nanomaterials for the Selective Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide in Air. Sensors 2017, 17, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17020391

Llobet E, Brunet J, Pauly A, Ndiaye A, Varenne C. Nanomaterials for the Selective Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide in Air. Sensors. 2017; 17(2):391. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17020391

Chicago/Turabian StyleLlobet, Eduard, Jérôme Brunet, Alain Pauly, Amadou Ndiaye, and Christelle Varenne. 2017. "Nanomaterials for the Selective Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide in Air" Sensors 17, no. 2: 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17020391