2.1. Wet Electrodes

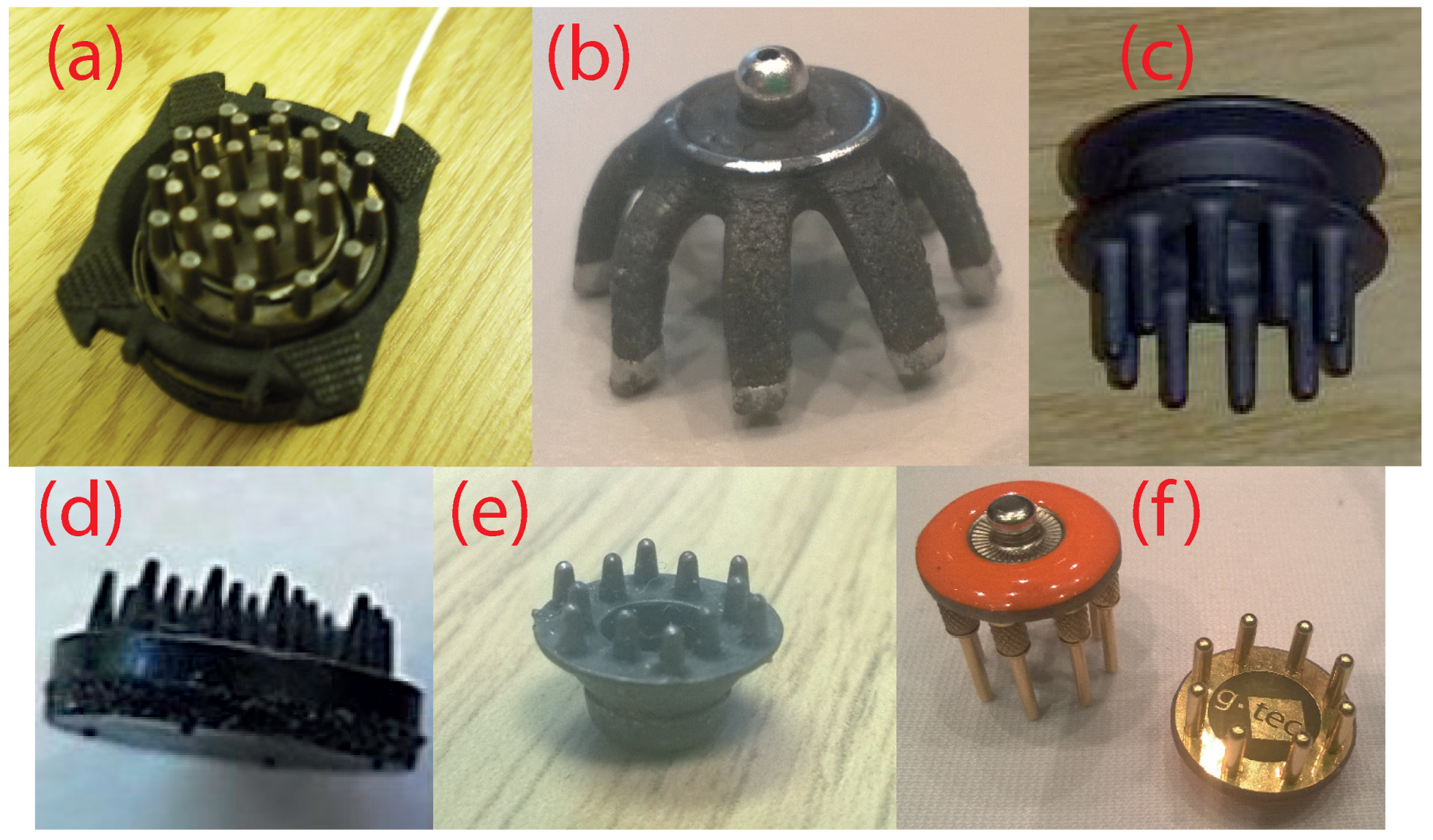

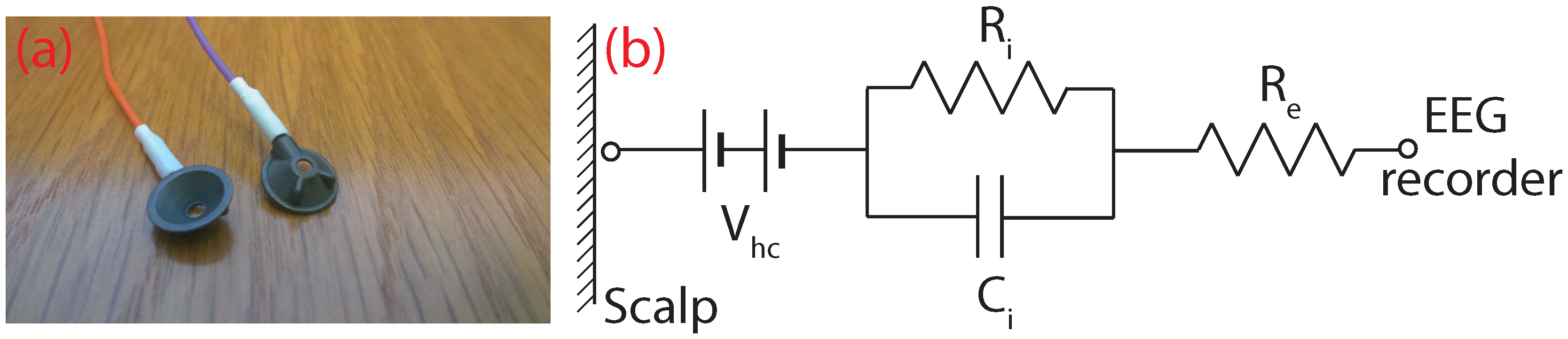

Wet EEG electrodes, such as the ones shown in

Figure 2a, are filled with an electrolytic (conductive) gel and put into a cap or glued to various positions along the scalp in order to make an electrical connection with the human body. In essence, the electrode is a transducer that converts ionic currents coming from the human body into electron currents that can be measured by conventional electronics. The electrical equivalent circuit of a wet electrode is shown in

Figure 2b.

represents the half-cell potential of the electrode, which occurs in the presence of charge carriers (ions) concentrated at the electrode-electrolyte interface and which causes a long-term drift in the recorded potentials [

11].

and

are parameters that determine the impedance of the electrode-electrolyte interface, and

specifies the material resistance of the electrode [

11].

Standard wet electrodes are made from a silver (Ag) base coated with silver chloride (AgCl), which is then sintered (heated below the meting point) to improve the electrical properties. These silver/sliver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrodes offer excellent electro-physiology recording properties. Firstly, Ag/AgCl electrodes have a very low half-cell potential, meaning better drift and noise performance at DC and low frequency measurements [

11]. They are also non-polarisable, which gives them long-term stability and lower susceptibility to movement artefacts [

12]. Polarisation is an undesired effect, which occurs when there is a build-up of charge carriers at the electrode-electrolyte interface, which acts as an insulating barrier, such that current is no longer able to pass.

In addition to the electrode material, for good quality recordings, a conductive gel and a skin preparation stage are required. The gel serves as a conductive medium for the ionic currents coming from the body, as it has an abundance of Cl-ions. It also maximizes the skin contact area (even through hair), effectively lowering the contact impedance of the electrode, and acts as a mechanical buffer maintaining contact with the skin during movement of the electrode. To complement the gel, skin abrasion, removing parts of the epidermis, is often performed before EEG experiments. This lowers the electrode-scalp contact impedance, but it is unpleasant to users and poses a risk of infection [

13]. High quality EEG recordings can be recorded using modern instrumentation even with contact impedances higher than 40 kΩ [

13], although total impedances below 5 kΩ are still the target for clinical practice [

14].

2.2. Dry Electrodes

Without the conductive gel present in a dry electrode, it is the material on the surface of the electrode that dominates the performance in terms of noise and contact impedance. Particularly challenging is the recording of low frequency components, which are contaminated by both low frequency 1/

f noise and drift in the half-cell potential. The work in [

15] characterized seven different electrode materials (tin, silver, sintered Ag/AgCl, disposable Ag/AgCl, gold, platinum and stainless steel), and the different performances are summarized in

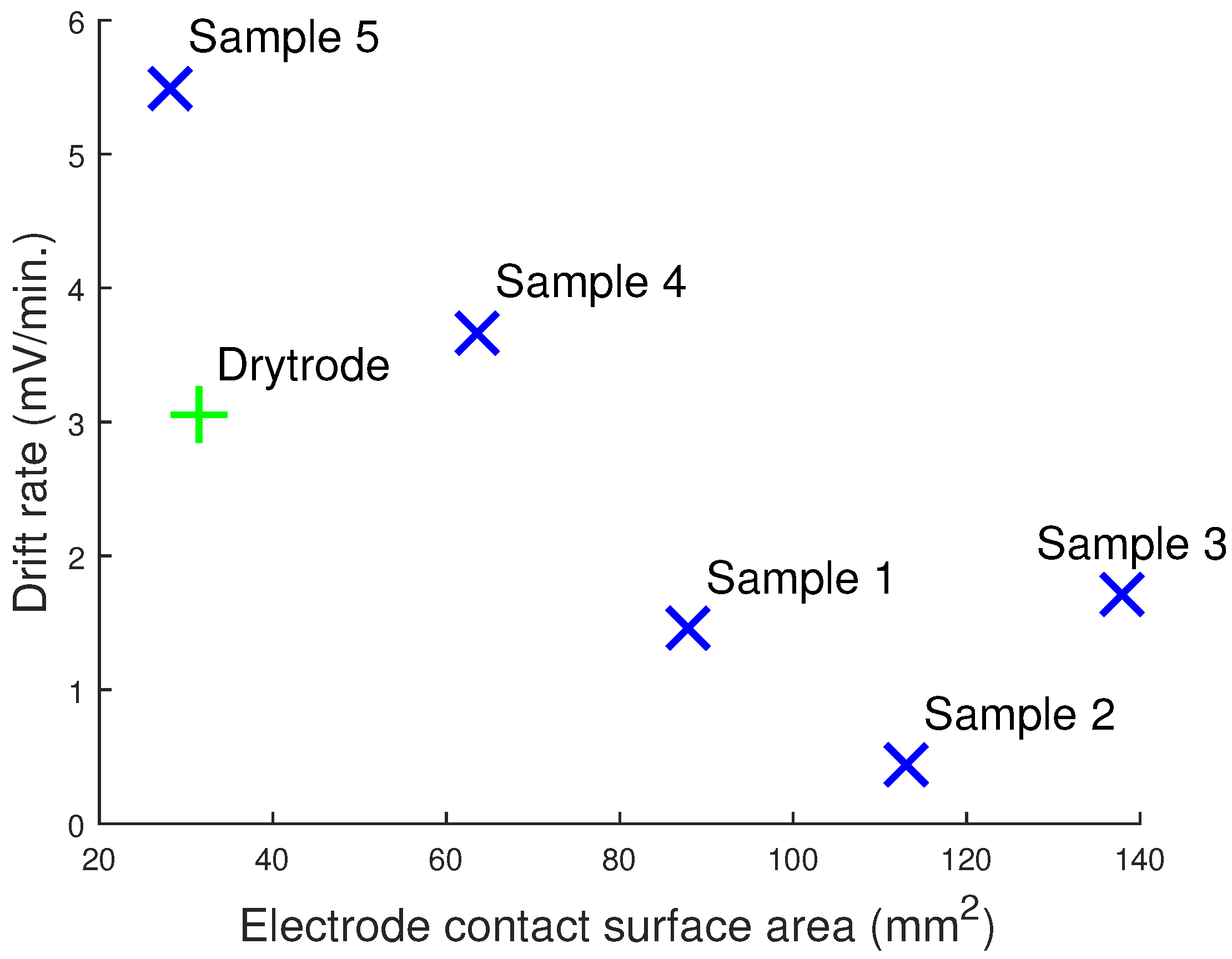

Table 1. Ag/AgCl has the best performance for low noise, low frequency measurements, but silver and gold-plated silver electrodes also provided results good enough for practical EEG recordings. For example, the low frequency drift of silver electrodes stabilized after approximately 15 min, somewhat longer than the one minute for Ag/AgCl, but still feasible, especially given the large input ranges of modern amplifiers, which allows recording despite large drift values. Another study on electrode coatings [

16] confirmed that the low frequency drift rate decreases over time, such that silver electrodes eventually come to a stable potential.

As a result, dry EEG electrodes have been reported using a number of different materials for the body contact. To our knowledge, the first occurrence in the literature of dry EEG electrodes is a paper from 1994 [

17] (although references to dry ECG electrodes for heart monitoring date back to the 1960s [

18]). The work in [

17] presented a dry active electrode for EEG recordings based on a 3-mm steel disk coated with nitride on one side and an impedance converting amplifier on the other. This new electrode was compared with wet Ag/AgCl electrodes for different evoked potentials, and the authors state that it had a similar performance. The paper briefly discusses the low frequency motion artefacts present with the dry electrodes and suggests that they can be removed by reducing the size of the electrode.

Since then, a wide number of materials have been considered for making dry EEG electrodes [

19,

20,

21,

22]. The commercially available g.SAHARA electrodes [

9,

23] use gold and a similar closely-positioned impedance-converting amplifier approach. The work in [

23] clearly shows that such electrodes are suitable for brain-computer interface applications with some disadvantages in the lower frequency (<3 Hz) performance. The work in [

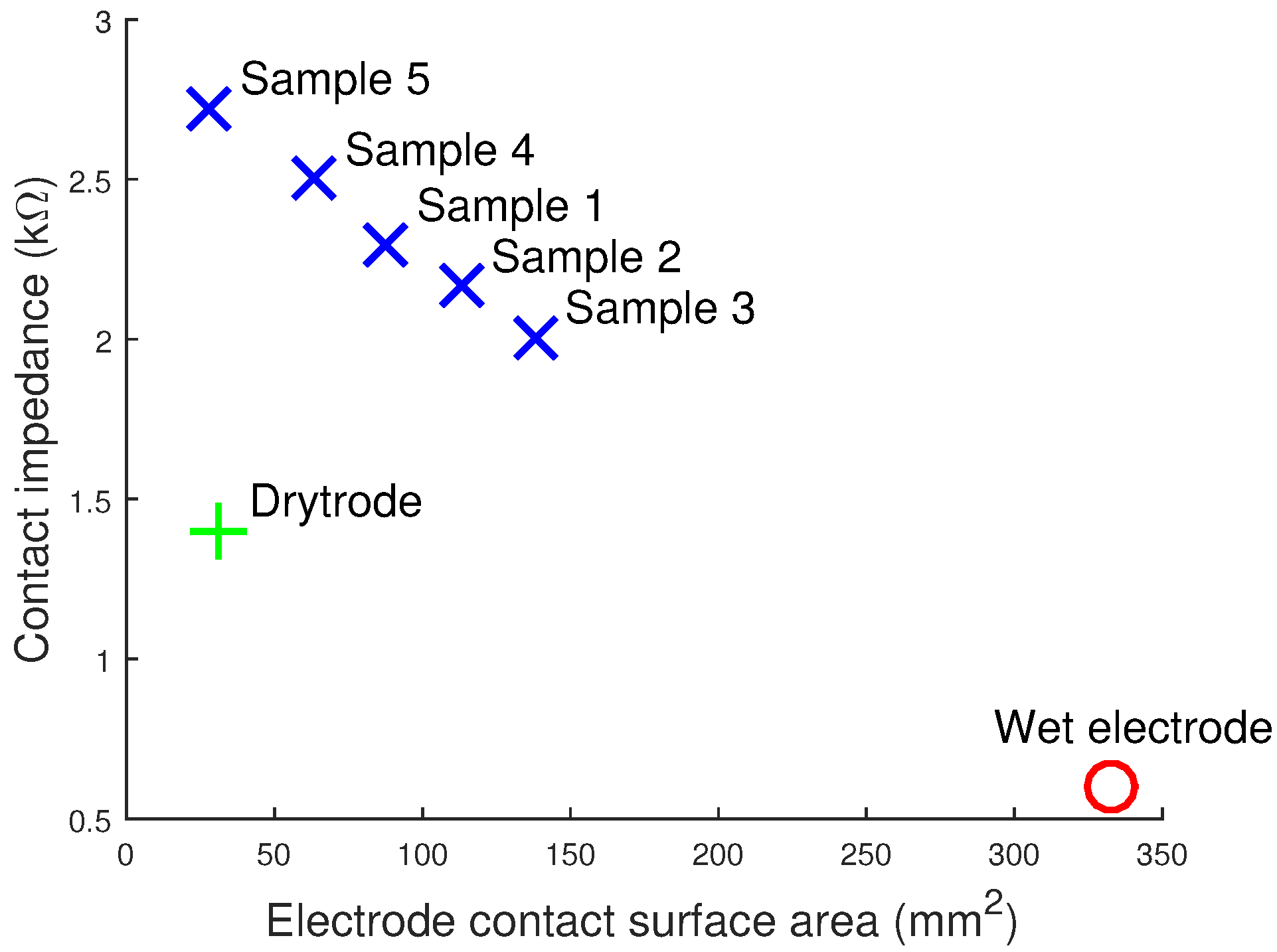

24] used a conductive polymer rather than metal and showed that the electrode impedance varied linearly with the surface contact area and that the polymer electrodes had better long-term stability in comparison to wet electrodes.

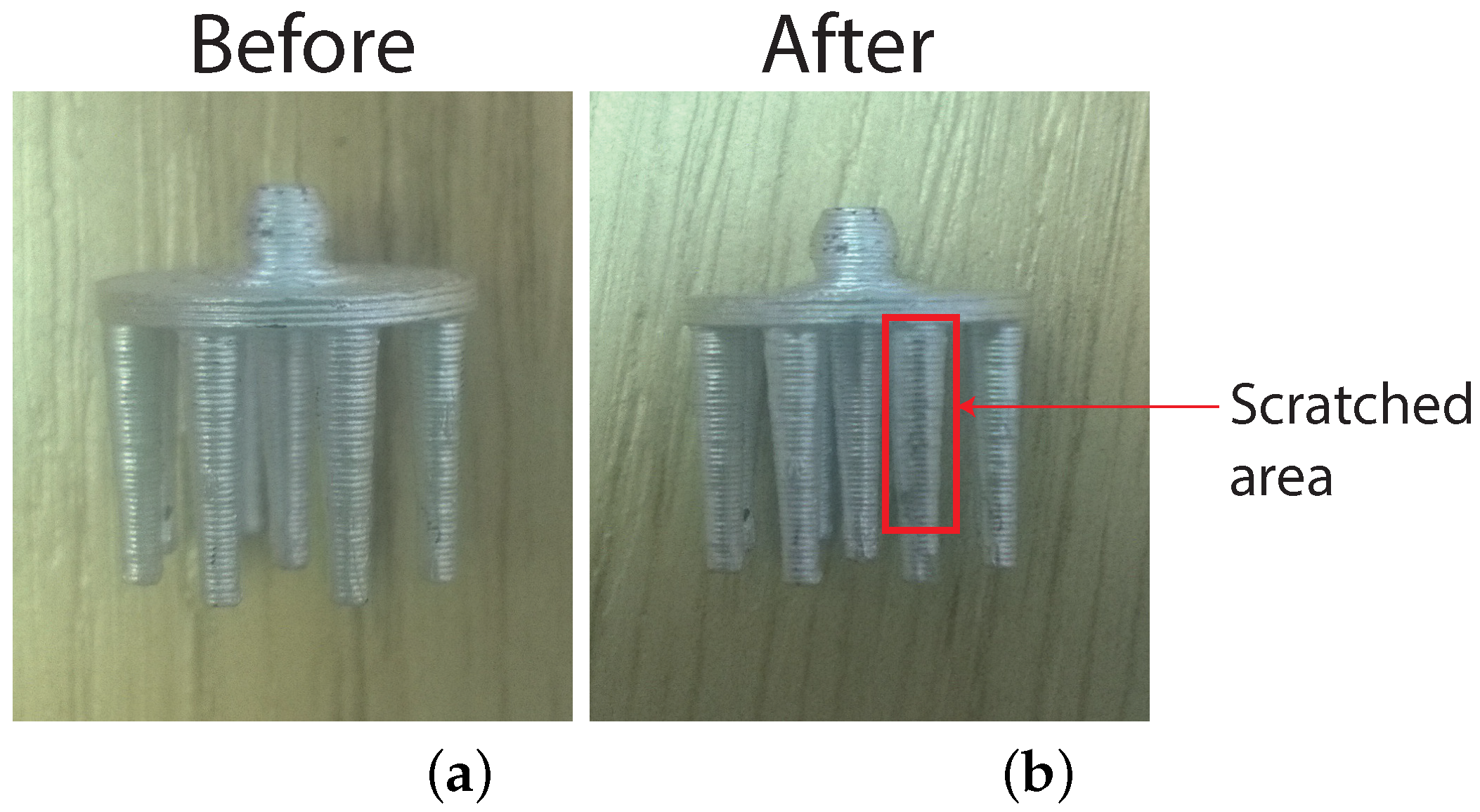

Although the fingered electrode approach (

Figure 1) is the most common, a number of alternative electrode shapes has been considered and combined with novel materials to form dry electrodes. The work in [

25] used multiple small Ag/AgCl bristles rather than fingers to connect to the skin. Most test subjects reported that the bristle type of electrode was more comfortable than rigid pin electrodes, and compared to gel-based electrodes, the bristle electrodes were found to have similar performance in the 7–44-Hz frequency range. The work in [

26,

27] presented microneedle-based electrodes, which penetrate the outer layer of the skin in order to make a better contact. The work in [

26] found that silver chloride (AgCl)-coated needles achieved better contact impedance than silver-only needles of the same type, although they were designed for usage on the forehead, which has no hair, and this makes them impractical for other hairy locations along the human scalp essential for EEG. The work in [

27] used an array of carbon nanotubes as the skin-penetrating needles. The performance of these dry electrodes was similar to wet electrodes, but again, they were placed at non-hairy sites, and no comments were made regarding the usability of microneedle-based electrodes for haired sites. In addition, the authors state that the bio-compatibility properties of carbon nanotubes are unknown and that further research is needed regarding the safety aspects of carbon nanotubes.

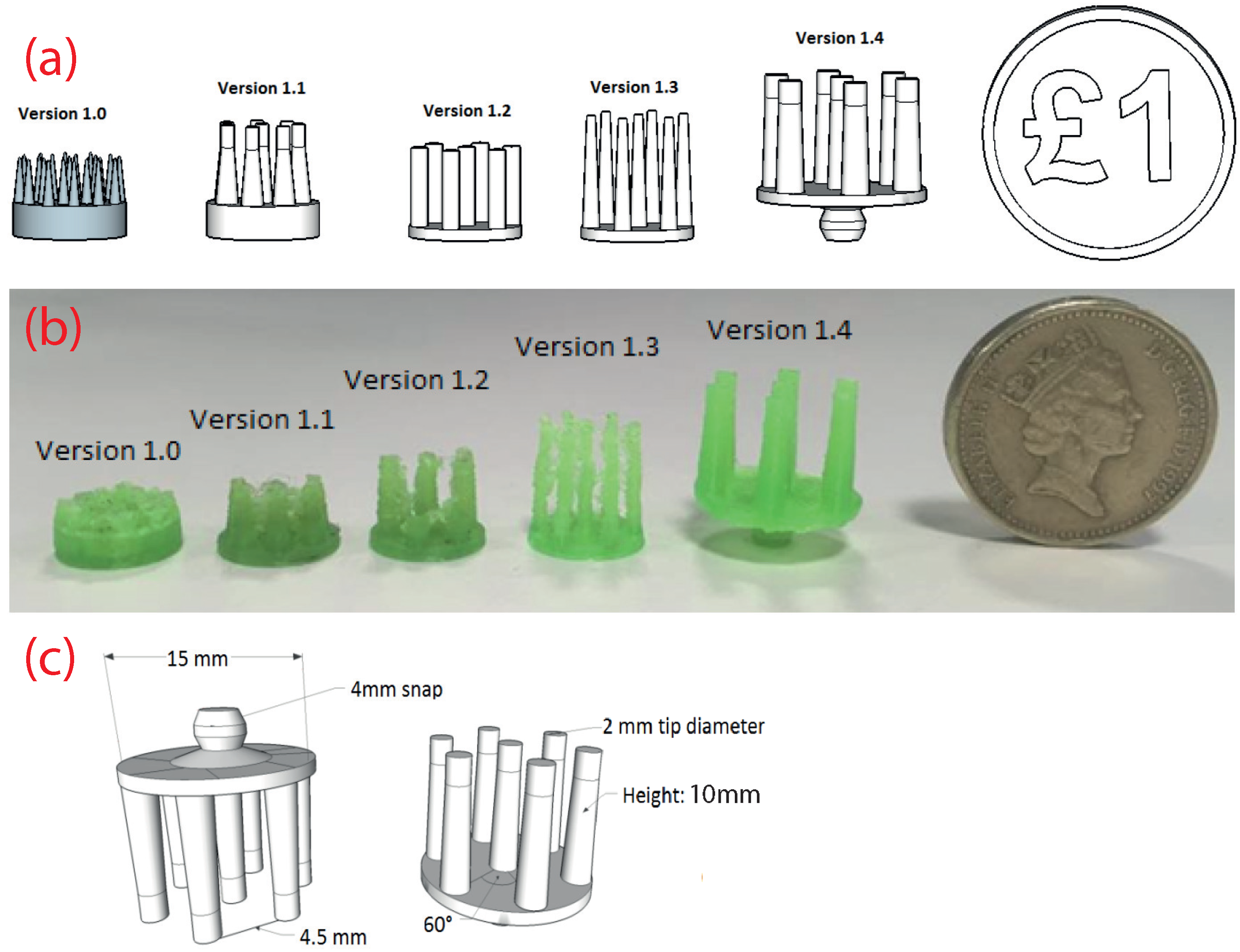

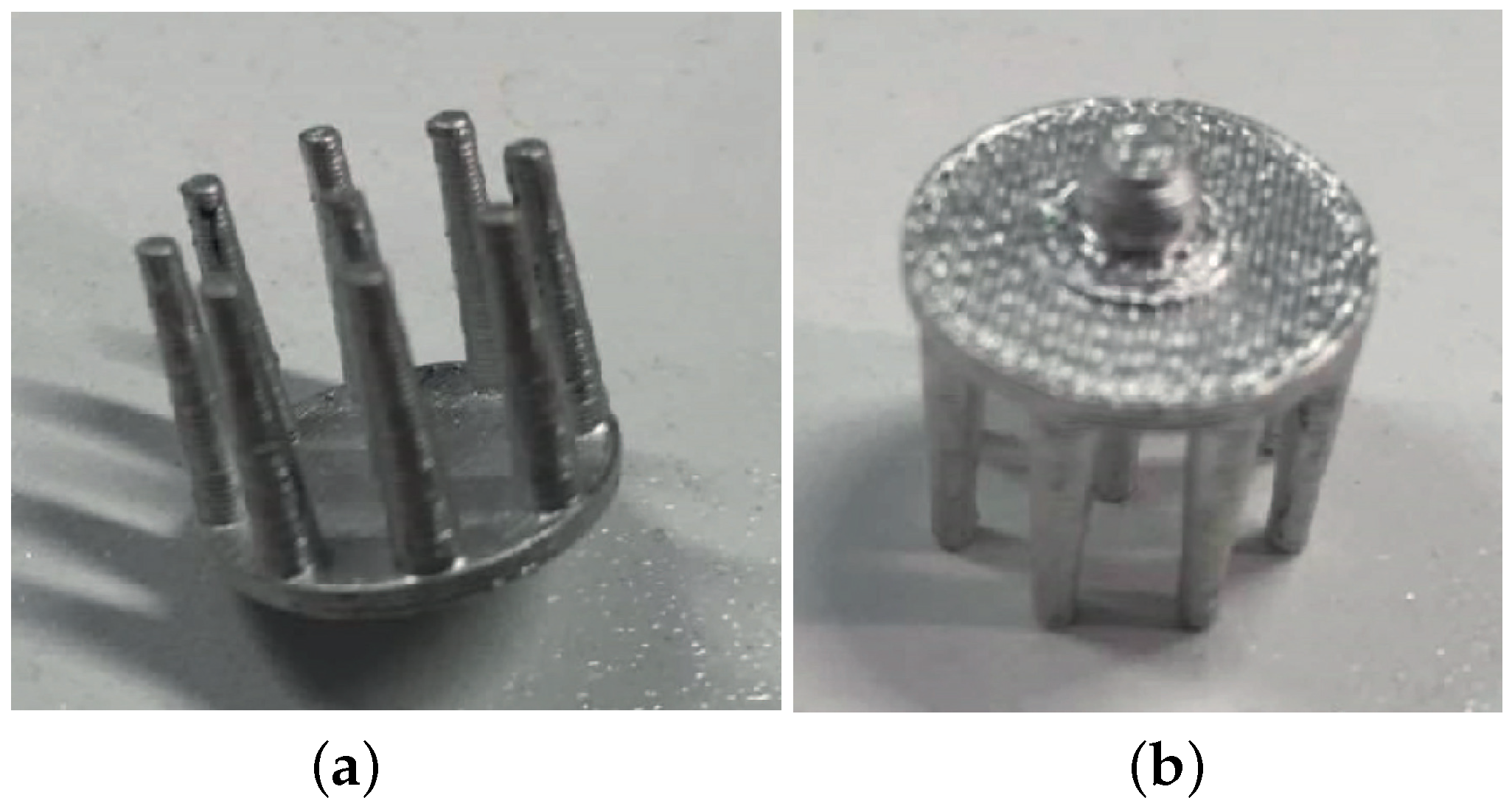

To our knowledge, 3D printing of EEG electrodes has not been considered in detail before. One online publication [

28] indicates that a printed conductive polymer can be used to acquire EEG signals using a fingered electrode approach with gel, but no details on the design, implementation, manufacturing or performance are given. The work in [

29] used a high resolution 3D printer to make a microneedle-type electrode. This dry electrode contained 180 needles with 250-

m spacing, which were 3D printed and then coated with gold to achieve conductivity. Again, they were tested only at the non-hairy Fp1 and Fp2 EEG sites.

Our work presents the design and performance of fingered dry 3D printed EEG electrodes for the first time. We specifically restrict the manufacturing to desktop-grade 3D printers in order to give a low cost and readily accessible process for users to make and customize their own electrodes.