Development of a HIV-1 Virus Detection System Based on Nanotechnology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Detection System | Sensitivity (TCID50) | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA | 105 | Requires multiple sampling steps and reagents |

| PCR | 5–100 | Requires parallel testing of external standards, complex multistep manipulations [e.g., labor-intensive sample preparation (plasma separation and RNA extraction), amplification (expensive reagents), and detection] |

| Cell Culture | 104 | Requires skilled technicians, time-consuming and costly. Some viruses cannot be cultured |

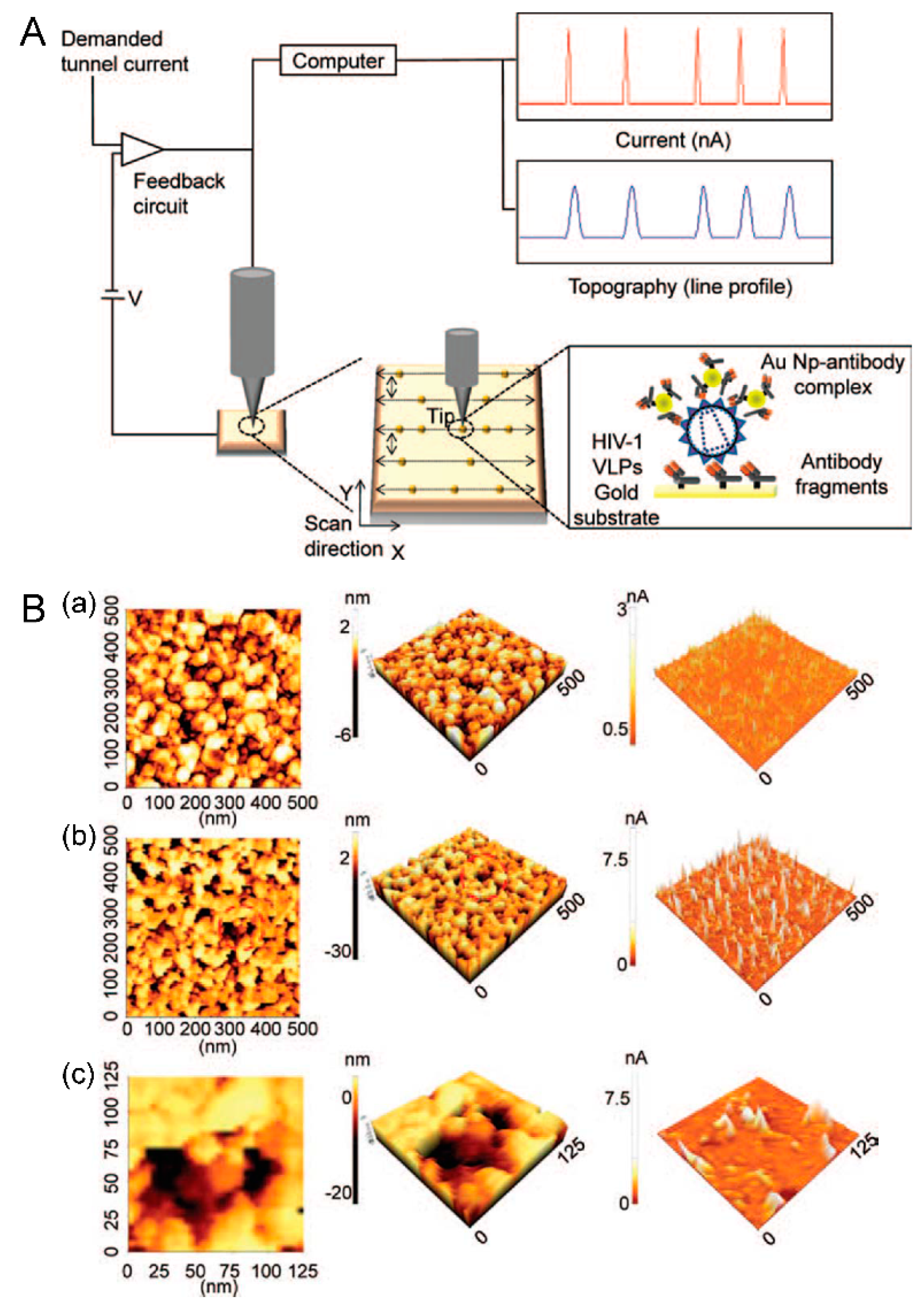

2. Electrical Detection System Based on Scanning Tunneling Microscopy

3. Electrochemical Detection Systems Based on Direct Electron Transfer from Virus Particles

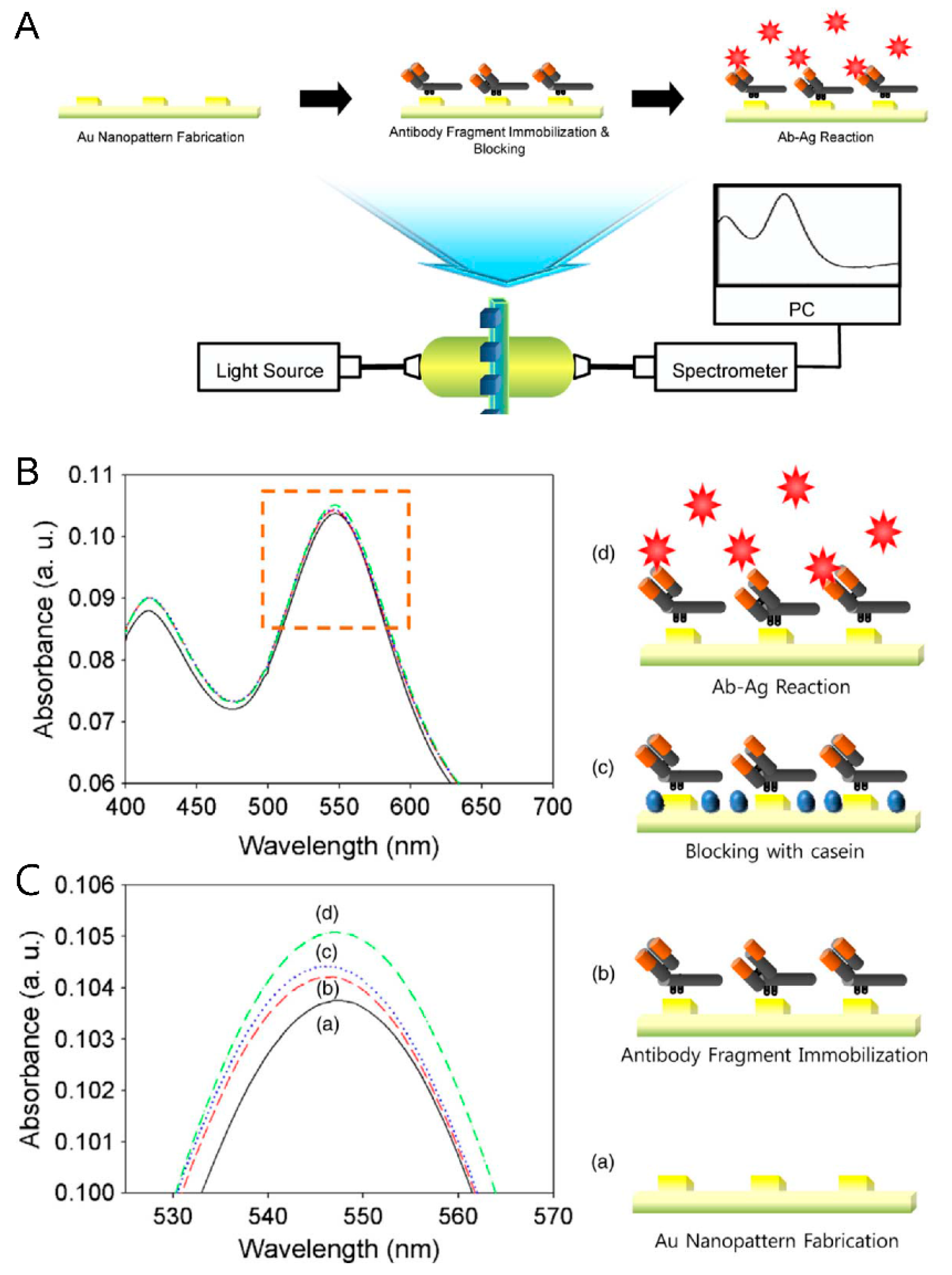

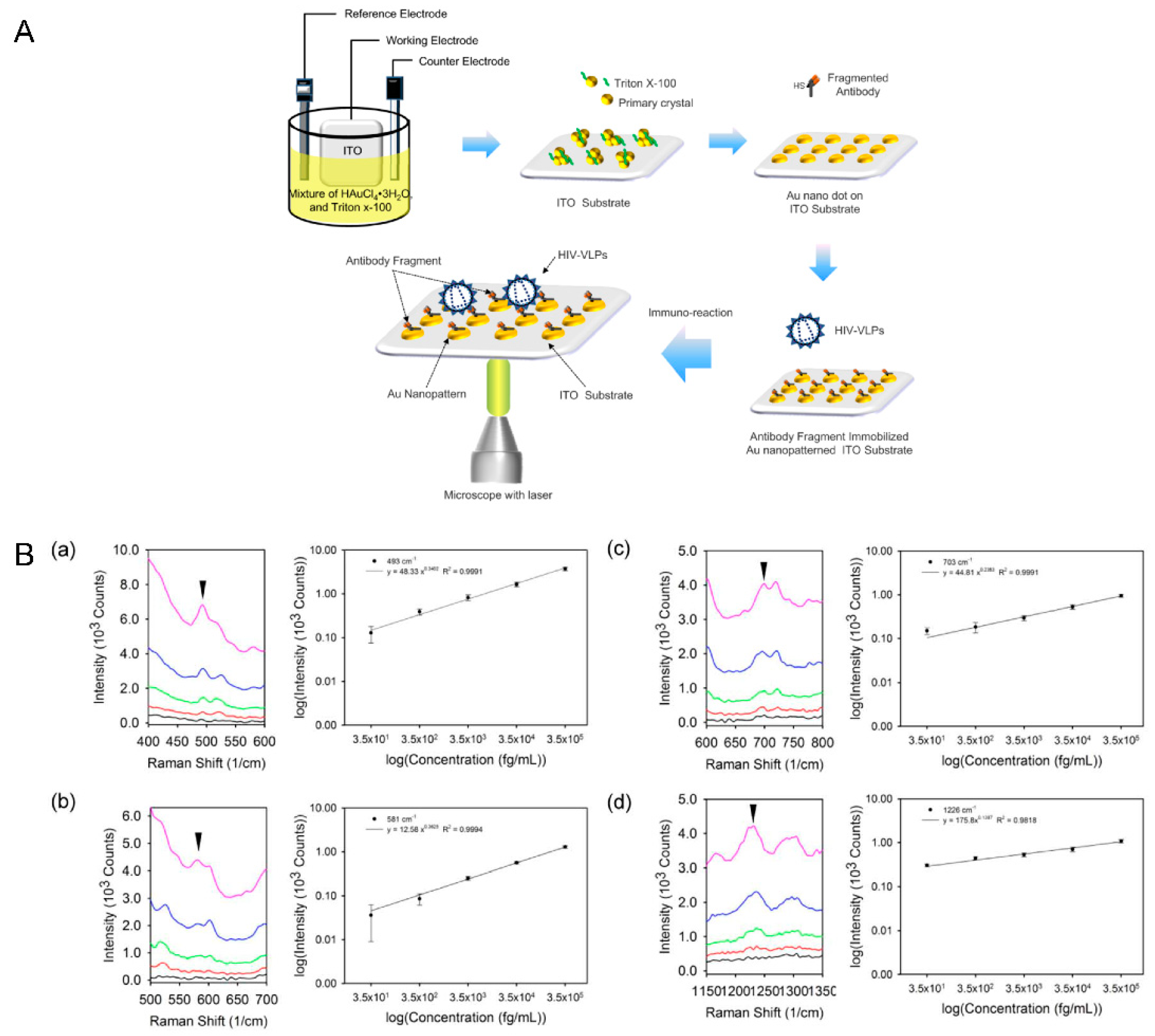

4. Optical Detection Systems Based on Plasmon Nanoparticles

5. Outlook

| Detection System | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical (STM) | Vertical configuration: Applicable to multiple analysis with appropriate combinatorial design of detection probes Low detection limit | Time consuming Requires labeling material (conducting or semiconducting) |

| Electrochemical (CV) | Simple to operate Labeling material is not necessary | Sensitivity of electrochemical signal without using enzyme is very low Current flow is attenuated by biomaterials Degradation or denaturation of biomaterials might occur Not completely defined where the redox reaction occurring |

| Optical (LSPR) | Ease of operation High sensitivity | Not able to distinguish different binding events regarding multiple analysts |

| Optical (SERS) | Requires relatively lower laser intensity and longer wavelengths Rapid signal acquisition times Can be conducted under ambient conditions Broad wavenumber range Narrow band spectra | Still requires interdisciplinary research effort to develop highly sensitive and reliable system such as integration with micro fluidic assay |

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrescia, N.G.A.; Bamford, D.H.; Grimes, J.M.; Stuart, D.I. Structure Unifies the Viral Universe. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 795–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munoz-Berbel, X.; Godino, N.; Laczka, O.; Baldrich, E.; Xavier, M.F.; Javier, D.C.F. Impedance-Based Biosensors for Pathogen Detection. In Principles of Bacterial Detection: Biosensors, Recognition Receptors and Microsystems; Zourob, M., Elwary, S., Turner, A.P.F., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 341–376. [Google Scholar]

- Akira, S.; Uematsu, S.; Takeuchi, O. Pathogen Recognition and Innate Immunity. Cell 2006, 124, 783–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watts, J.M.; Dang, K.K.; Gorelick, R.J.; Leonard, C.W.; Bess, J.W., Jr.; Swanstrom, R.; Burch, C.L.; Weeks, K.M. Architecture and Secondary Structure of an Entire HIV-1 RNA Genome. Nature 2009, 460, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goff, S.P. Host Factors Exploited by Retroviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.J.; Upson, R.H.; Haugland, N.; Panchuk-Voloshina, M.; Zhou, J.; Haugland, R.P. Quenched BODIPY Dye-Labeled Casein Substrates for the Assay of Protease Activity by Direct Fluorescence Measurement. Anal. Biochem. 1999, 271, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drosten, C.; Gottig, S.; Schilling, S.; Asper, M.; Panning, M.; Schmitz, H.; Gunther, S. Rapid Detection and Quantification of RNA of Ebola and Marburg Viruses, Lassa Virus, Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus, Rift Valley Fever Virus, Dengue Virus, and Yellow Fever Virus by Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 2323–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaydos, C.A.; Crotchfelt, K.A.; Howell, M.R.; Kralian, S.; Hauptman, P.; Quinn, T.C. Molecular Amplification Assays to Detect Chlamydial Infections in Urine Specimens from High School Female Students and to Monitor the Persistence of Chlamydial DNA after Therapy. J. Infect. Dis. 1998, 117, 417–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebert, U.G. Measles Virus Infections of the Central Nervous System. Intervirology 1997, 40, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karst, S.M. Pathogenesis of Noroviruses, Emerging RNA Viruses. Viruses 2010, 2, 748–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Taton, T.A.; Mirkin, C.A. Array-Based Electrical Detection of DNA with Nanoparticle Probes. Science 2002, 295, 1503–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, A.; Pennazza, G.; Santonico, M.; Martinelli, E.; Roscioni, C.; Galluccio, G.; Paolesse, R.; Di Natale, C. An Investigation on Electronic Nose Diagnosis of Lung Cancer. Lung Cancer 2010, 68, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Chander, Y.; Goyal, S.M.; Cui, T. Carbon Nanotube Electric Immunoassay for the Detection of Swine Influenza Virus H1N1. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 3482–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiee, H.; Jahangir, M.; Inic, F.; Wang, S.Q.; Willenbrecht, R.B.M.; Giguel, F.F.; Tsibris, A.M.N.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Demirci, U. Actute On-Chip Detection through Label-Free Electrical Sensing of Viral Nano-Lysatem. Small 2013, 9, 2553–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ymeti, A.; Greve, J.; Lambeck, P.V.; Wink, T.; Stephan, W.F.M.; Tom, A.M.; Wijn, R.R.; Heideman, R.G.; Subramaniam, V.; Kanger, J.S. Fast, Ultrasensitive Virus Detection Using a Young Interferometer Sensor. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, P.; Tipple, C.A.; Lavrik, N.V.; Datskos, P.G.; Hofstetter, H.; Hofstetter, O.; Sepaniak, M.J. Enantioselective Sensors Based on Antibody-Mediated Nanomechanics. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75, 2342–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arntz, Y.; Seelig, J.D.; Lang, H.P.; Zhang, J.; Hunziker, P.; Ramseyer, J.P.; Meyer, E.; Hegner, M.; Gerber, C. Label-Free Protein Assay Based on a Nanomechanical Cantilever Array. Nanotechnology 2003, 14, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamarcje, E.; Miche, B.; Biebuyck, H.A.; Gerber, C. Golden Interfaces: The Surface of Self-Assembled Monolayers. Adv. Mater. 1996, 8, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Hou, J.G. High-Resolution Scanning Tunneling Microscopy for Molecules. Ultramicroscopy 2004, 98, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.C.; Oh, B.K.; Choi, J.W. Highly Sensitive Electrical Detection of HIV-1 Virus Based on Scanning Tunneling Microscopy. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, J.; Grunwald, T.; Nebling, E.; Piechotta, G.; Hintsche, R. Electrical Biochip Technology—A Tool for Microarrays and Continuous Monitoring. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 377, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, C.F.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, M.L.; Zhang, S.S. Hybridization Biosensor Using 2,9-Dimethyl-1,10-Phenantroline Cobalt as Electrochemical Indicator for Detection of Hepatitis B Virus DNA. Bioelectrochemistry 2008, 72, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toghill, K.E.; Compton, R.G. Electrochemical Non-Enzymatic Glucose Sensors: A Perspective and an Evaluation. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2010, 5, 1246–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.J.; Ma, J.R.; Zhao, F.Q.; Zeng, B.Z. Development of Amperometric Glucose Biosensor Through Immobilizing Enzyme in a Pt Nanoparticles/Mesoporous Carbon Matrix. Talanta 2008, 74, 1586–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.F.; Ye, J.S.; Zhang, W.D.; Li, C.M.; Luong, J.H.T.; Sheu, F.S. Selective and Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Glucose in Neutral Solution Using Platinum–Lead Alloy Nanoparticle/Carbon Nanotube Nanocomposites. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2007, 594, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.J.; Ju, H.X.; Wang, J. Electrochemical Sensors, Biosensors and Their Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Riklin, A.; Katz, E.; Williner, I.; Stockerand, A.; Buckmann, A.F. Improving Enzyme–Electrode Contacts by Redox Modification of Cofactors. Nature 1995, 376, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Oh, B.K.; Choi, J.W. Electrochemical Sensor Based on Direct Electron Transfer of HIV-1 Virus at Au Nanoparticle Modified ITO Electrode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 15, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, N.; Du, X.; Cao, Y.; Hu, F.; Li, T.; Jiang, Q. An Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Immunosensor for HIV p24 Based on Fe3O4@SiO2 Nanomagnetic Probes and Nanogold Colloid-Labeled Enzyme–Antibody Copolymer as Signal Tag. Materials 2013, 6, 1255–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheiri, F.; Sabzi, R.E.; Jannatdoust, E.; Shojaeefar, E.; Sedghi, H. A Novel Amperometric Immunosensor Based on Acetone-Extracted Propolis for the Detection of the HIV1 p24 Antigen. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2011, 26, 4457–4463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homola, J. Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensors for Detection of Chemical and Biological Species. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 462–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raether, H. Surface Plasmons on Smooth and Rough Surfaces and on Gratings; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wark, A.W.; Lee, H.J.; Corn, R.M. Long-Range Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging for Bioaffinity Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 3904–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.S.; El-Sayed, M.A. Gold and Silver Nanoparticles in Sensing and Imaging: Sensitivity of Plasmon Response to Size, Shape, and Metal Composition. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 19220–19225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Nath, S.; Kundu, S.; Esumi, K.; Pal, T. Solvent and Ligand Effects on the Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) of Gold Colloids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 13963–13971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, E.; Fendler, J.H. Exploitation of Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance. Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 1685–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, N.; Foley, K.; Tao, N. Integrated Label-Free Protein Detection and Separation in Real Time Using Confined Surface Plasmon Resonance Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 2546–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Fu, Q.; Peng, J.; Wang, Y.; Du, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhan, L. Gold Nanorod-Based Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor for Sensitive Detection of Hepatitis B Virus in Buffer, Blood Serum and Plasma. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.F.; Wang, S.F.; Huang, J.C.; Su, L.C.; Yao, L.; Li, Y.C.; Wu, S.C.; Chen, Y.M.; Hsieh, J.P.; Chou, C. Detection of Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1) Viruses Using a Localized Surface Plasmon Coupled Fluorescence Fiber-Optic Sensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 26, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.C.; Oh, B.K.; Choi, J.W. Highly Sensitive Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Immunosensor for Label-Free Detection of HIV-1. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2013, 9, 1018–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, H.; Lidstone, E.A.; Jahangir, M.; Inic, F.; Hanhauser, E.; Henrich, T.J.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Cunningham, B.T.; Demirci, U. Nanostructured Optical Photonic Crystal Biosensor for HIV Viral Load Measurement. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inci, F.; Tokel, O.; Wang, S.Q.; Gurkan, U.A.; Tasoglu, S.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Demirci, U. Nanoplasmonic Quantitative Detection of Intact Viruses from Unprocessed Whole Blood. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4733–4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlücker, S. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: Concepts and Chemical Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4756–4795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanmaire, D.L.; van Duyne, R.P. Surface Raman Spectroelectrochemistry: Part 1. Heterocyclic, Aromatic, and Aliphatic-Amines Adsorbed On Anodized Silver Electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1977, 84, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.G.; Creighton, J.A. Anomalously Intense Raman-Spectra of Pyridine at a Silver Electrode. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 5215–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, C.L.; McFarland, A.D.; van Duyne, R.P. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniukevic, J.; Hakki Boyaci, I.; Goktug Bozkurt, A.; Tamer, U.; Ramanavicius, A.; Ramanaviciene, A. Magnetic Gold Nanoparticles in SERS-Based Sandwich Immunoassay for Antigen Detection by Well Oriented Antibodies. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 43, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neng, J.; Harpster, M.H.; Wilson, W.C.; Johnson, P.A. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Detection of Multiple Viral Antigens Using Magnetic Capture of SERS-Active Nanoparticles. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 41, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmukh, S.; Jones, L.; Driskell, J.; Zhao, Y.; Dluhy, R.; Tripp, R.A. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Respiratory Virus Molecular Signatures Using a Silver Nanorod Array SERS Substrate. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.C.; Oh, B.K.; Choi, J.W. Rapid and Sensitive Determination of HIV-1 Virus Based on Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-H.; Oh, B.-K.; Choi, J.-W. Development of a HIV-1 Virus Detection System Based on Nanotechnology. Sensors 2015, 15, 9915-9927. https://doi.org/10.3390/s150509915

Lee J-H, Oh B-K, Choi J-W. Development of a HIV-1 Virus Detection System Based on Nanotechnology. Sensors. 2015; 15(5):9915-9927. https://doi.org/10.3390/s150509915

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jin-Ho, Byung-Keun Oh, and Jeong-Woo Choi. 2015. "Development of a HIV-1 Virus Detection System Based on Nanotechnology" Sensors 15, no. 5: 9915-9927. https://doi.org/10.3390/s150509915