2.1. Hydroformylation of cyclohexene at different pressures

The additive effect of LiCl was already reported in the literature [

11–

13] but it was briefly examined in this work as well.

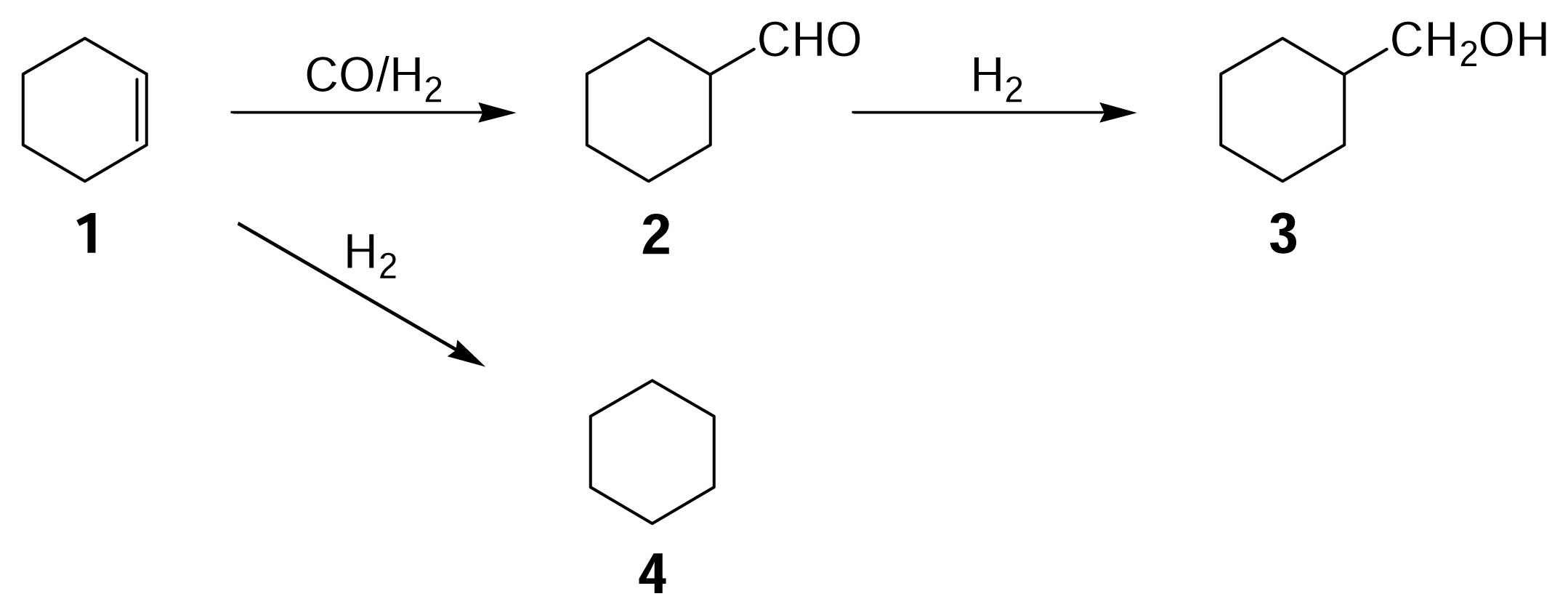

Table 1 gives the results obtained with different amounts of LiCl used. When LiCl was absent or its amount was smaller compared to that of Ru

3(CO)

12, hydrogenation of cyclohexene to chclohexane and formation of methane and other hydrocarbons mainly occurred but hydroformylation scarcely took place. After these reaction runs, the remaining liquid mixture was black, suggesting that Ru

3(CO)

12 species released CO moieties and changed to ruthenium metal colloids. At a larger LiCl/Ru

3(CO)

12 ratio of 4/3, however, hydroformylation was observed to proceed, giving cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde

2 and cyclohexanemethanol

3 along with cyclohexane

4 (

Scheme 1), but undesired hydrocarbons were not formed. The reaction mixture was reddish brown in color, indicating that the catalyst still remained in the form of Ru

3(CO)

12 after the reaction. The following experiments were made to examine the influence of CO

2 and H

2 pressures at this LiCl/Ru

3(CO)

12 ratio of 4/3.

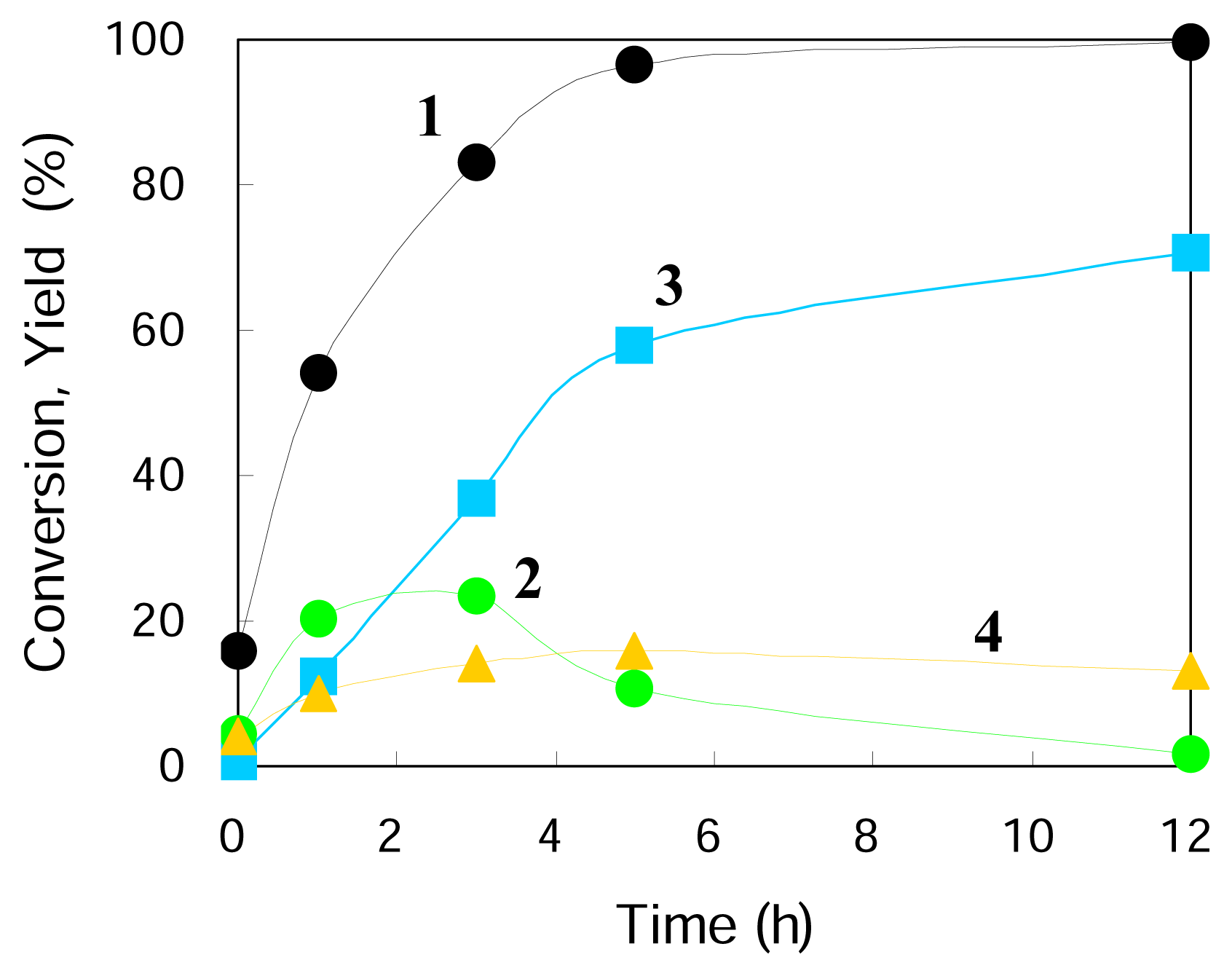

Figure 1 gives typical changes of total conversion and product yields with reaction time. The reaction was timed just after the reaction temperature reached 423 K and so the reactions occurred to some extent at increasing temperatures (the conversion and the yields are not zero at a reaction time of zero). Under the conditions used the three main products were observed to form from cyclohexene

1, including cyclohexanecarboxaldehyde

2, cyclohexylmethanol

3, and cyclohexane

4 (

Scheme 1). The conversion of

1 was almost completed in 5 h and the yield of the hydroformylation product

2 increased with time, had a maximum at about 2 h, and then decreased gradually. After about 2 h the yield of its hydrogenated product

3 went over the yield of

2 and further increased with time. Thus

3 was consecutively formed through the hydrogenation of

2. The yield of

4, hydrogenation product of

1, increased slightly within 3 h and then did not change so much after the disappearance of the substrate

1. It is indicated that the two paths from

1 to

2 (hydroformylation) and from

1 to

4 (hydrogenation) are parallel reactions. Very minor products such as cyclohexylmethyl cyclohexanecarboxylate, methylenecyclohexane, 1-methyl-1-cyclohexene, and 3-methyl-1-cyclohexene were detected.

The present hydroformylation with CO

2 and H

2 is a two step process with the reverse water gas shift reaction (RWGSR) followed by the hydroformylation with CO formed.

Table 2 shows the amounts of

2,

3 and CO gas detected during the reaction run of

Figure 1. The amount of CO gas is comparable to those of

2 and

3, so the RWGSR is assumed to go faster compared with the following hydroformylation with CO formed and the latter determines the overall rate of the hydroformylation of

1 with CO

2 and H

2 to

2.

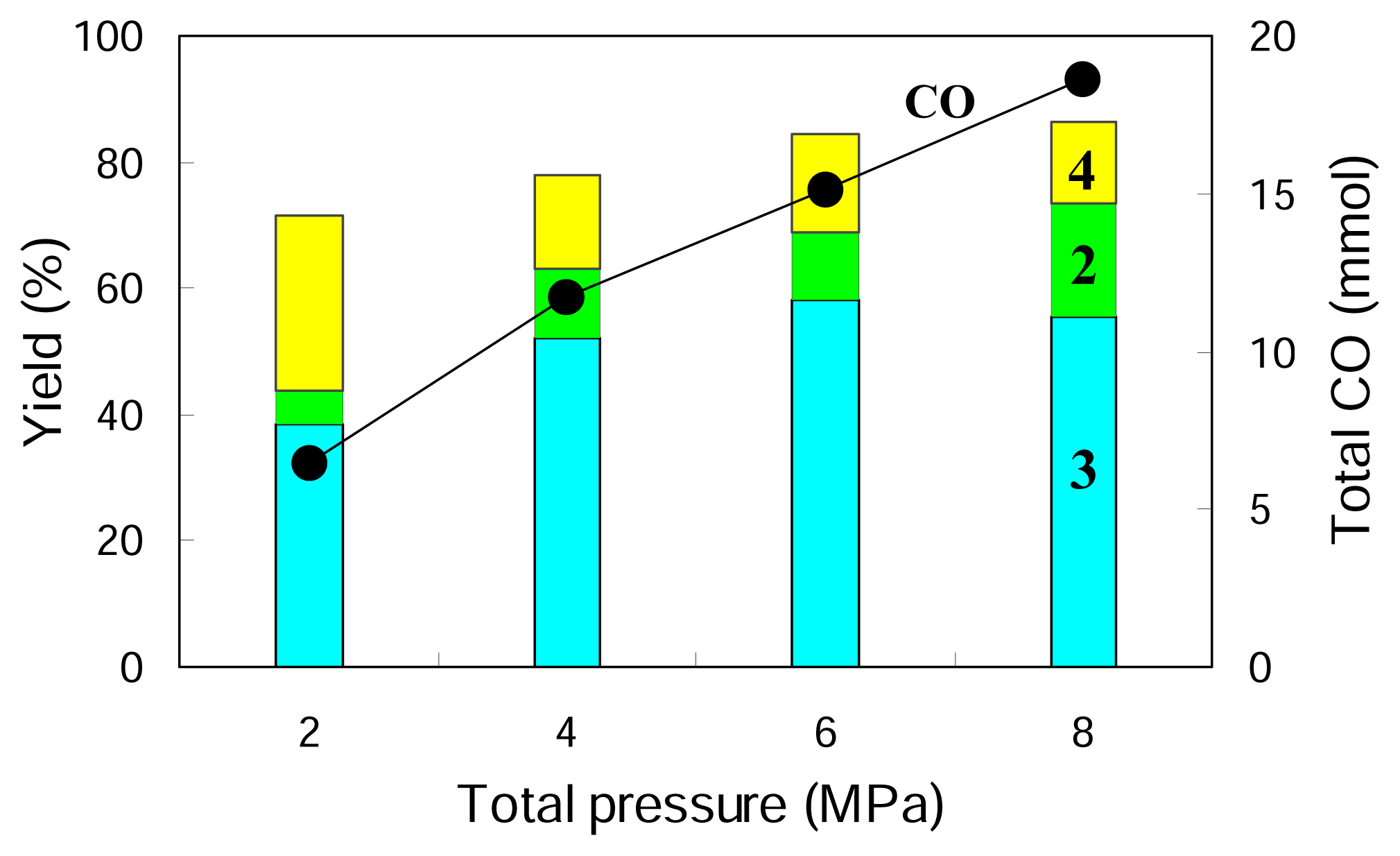

Next the influence of CO

2 and H

2 pressures has been examined.

Figure 2 gives the results obtained at different total pressures while keeping the ratio of CO

2:H

2 to 1:1. It is indicated that the increasing total pressure promotes the hydroformylation and increases the yields of

2 and

3 but suppresses the direct hydrogenation of

1, decreasing the yield of

4. A higher pressure of 8 MPa gives a further increased yield of the aldehyde

2 while it does not change the yield of its hydrogenated product

3 so much. Higher total pressure is beneficial for higher rate of hydrofomylation and higher selectivity to the hydroformylation product (aldehyde) compared to its further hydrogenated product (alcohol).

Figure 3 shows the effects of CO

2 and H

2 pressures at certain H

2 and CO

2 pressures. The effects of CO

2 pressure are similar to those of the total CO

2 + H

2 pressure as above-mentioned.

Figure 3(b) shows that increasing H

2 pressure enhances the rates of hydrofomylation and hydrogenation reactions. The yield of

3 increases with H

2 pressure, while the yield of

2 decreases. The yield of

4 increases on going from 1 MPa to 2 MPa but does not change at higher H

2 pressures. Higher H

2 pressure is suitable for higher selectivity for the hydrofomylation and the subsequent hydrogenation than the undesired direct hydrogenation to

4.

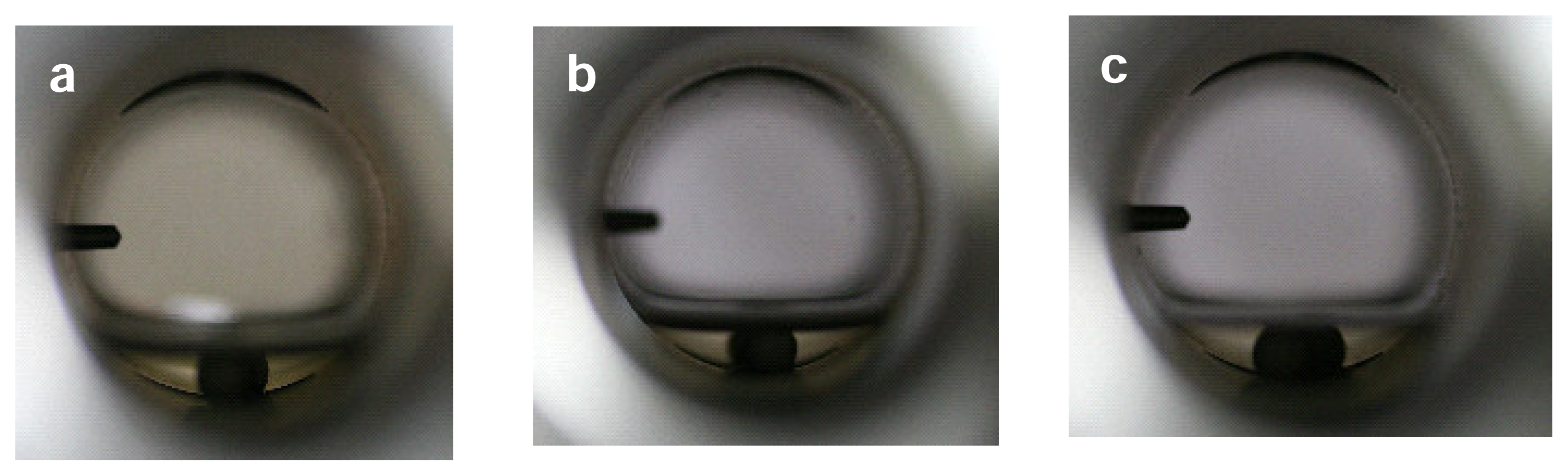

2.2 Phase behavior and high pressure FTIR

Under the reaction conditions used, the reaction mixture is a biphasic system of gas and liquid phases. The phase behavior was confirmed by visual observations at 403 K (

Figure 4), which is a little lower than the reaction temperature (423 K) due to limitation of the observation system used. The presence of CO

2 seems to cause the expansion of the liquid phase but marginally. The hydrofomylation and hydrogenation reactions occur in the liquid phase (NMP solvent).

Previously the present authors show from in situ high pressure FTIR measurements that dense CO

2 molecules may strongly interact with organic molecules and modify the reactivity of some of their functional groups [

14–

17]. There are indeed strong interactions between dense CO

2 molecules and an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde, cinnamaldehyde, in particular with its carbonyl group. This is of significance in promoting the selective hydrogenation to the corresponding unsaturated alcohol, cinnamyl alcohol. To examine such a chemical effect of CO

2 for the present cases, similar FTIR measurements were also made for the substrate

1 and the hydrofomylation product

2, which were dissolved in the dense CO

2 medium at different pressures.

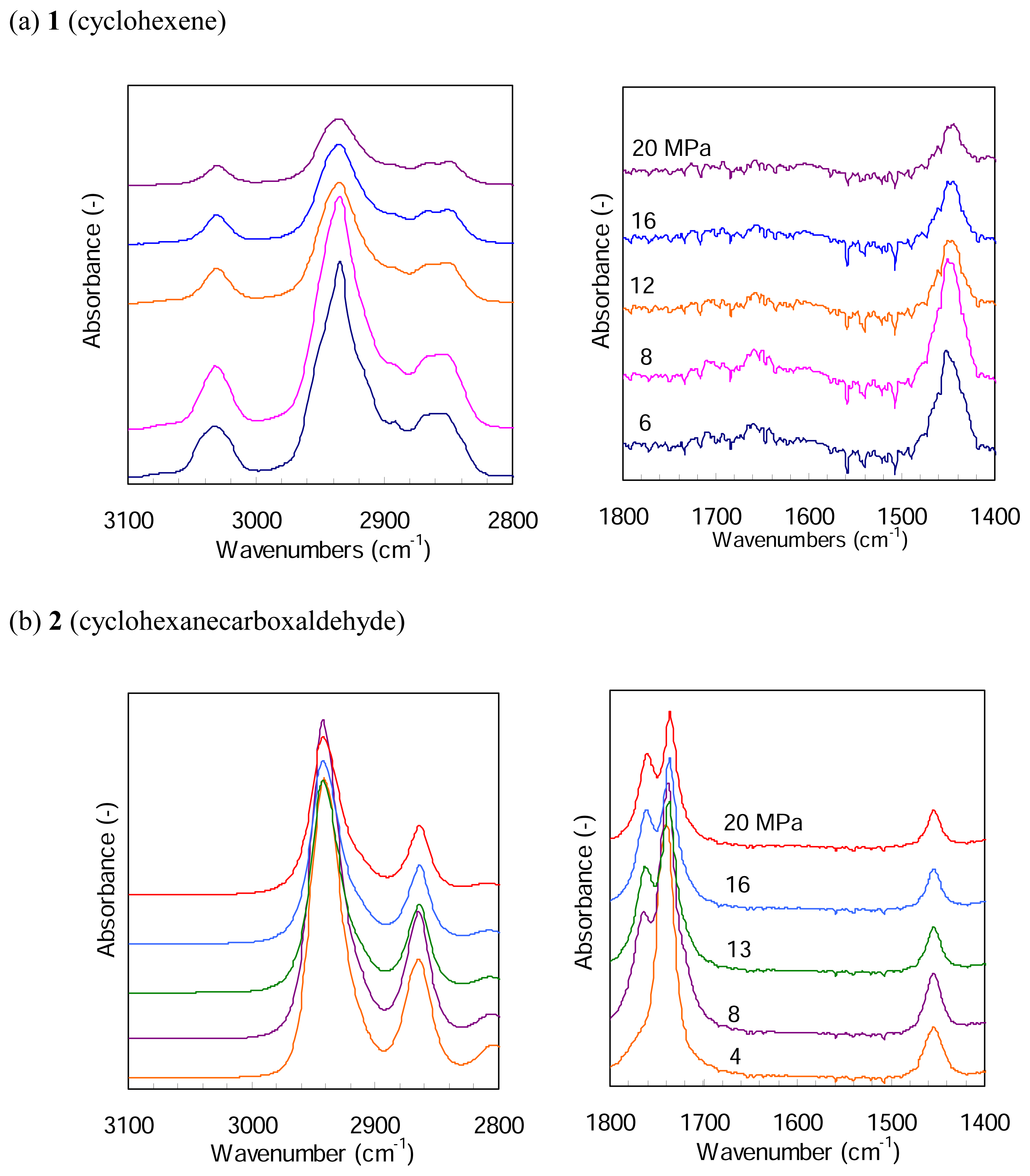

Figure 5 presents FTIR spectra of

1 and

2 in a mixture of 4 MPa H

2 and CO

2 at different pressures and at 387 K.

Figure 5(a) shows an IR band at around 3030 cm

−1 and a very weak band at around 1660 cm

−1, which are assigned to the absorption of =CH- and -C=C-, respectively. The both bands decrease in the strength with CO

2 pressure, due to a simple dilution. Their peak positions little change with the pressure. For

2, on the other hand,

Figure 5(b) indicates a single peak at 1743 cm

−1 assignable to the absorption of C=O at a CO

2 pressure of 4 MPa and a new shoulder peak appears at 8 MPa; it marginally increases with the pressure but the peak position remains almost unchanged. The two IR bands assignable to -CH

2- in the region of 2980 - 2840 cm

−1 do not change their peak positions with CO

2 pressure. Thus we believe that dense CO

2 molecules indicate no effects on the reactivity of

1 and

2 to hydrogenation and hydroformylation, respectively, under the present CO

2 pressure conditions.

2.3. Pressure effects

The structure of Ru complexes prepared at different CO

2 and H

2 pressures was examined by FTIR measurements.

Figure 6 shows that the complexes (a) – (c) exhibit three strong and two weak IR bands in the CO region at 2038, 2018, 1999, 1976, and 1949 cm

−1, which are very similar independent of the pressures of CO

2 and H

2 used for the preparation of them. Previously Tominaga and Sasaki observed similar IR bands [

11] and pointed out that these IR bands indicated the presence of two different Ru complexes, [H

3Ru

4(CO)

12]

−1 and [HRu

3(CO)

11]

−1, which may be active for the hydrogenation of CO

2 to CO and the hydrofomylation of alkene with CO, respectively. Those two Ru complexes should also be formed in our cases and their structure and relative quantities do not change with the CO

2 and H

2 pressures under the present conditions. Thus, other factors should be considered to explain the pressure effects observed.

The reactions occur in the liquid phase (NMP) under the conditions used, as confirmed by visual observations (

Figure 4). When CO

2 and H

2 pressures are raised, larger quantities of these gaseous reactants are dissolved in the liquid phase and this promotes the hydroformylation and the following hydrogenation. Thus, the yields of

2 and

3 tend to increase with the CO

2 and H

2 pressures (

Figures 1–

3). It is interesting to note that the yield of

4 does not increase with H

2 pressure and the coexistence of CO

2 may be important for this. When H

2 pressure is raised at a certain CO

2 pressure, the dissolution of CO

2 into the liquid phase may also be facilitated. The dissolved CO

2 species should suppress the direct hydrogenation of

1 to

4. This may be due to a simple dilution effect that the reactants of

1 and H

2 in the liquid phase are diluted by the dissolved CO

2 molecules. The FTIR results do not indicate that the reactivity of

1 is modified through interactions with the CO

2 molecules. Additional reaction runs were attempted with the same catalyst system but at lower reaction temperatures (393 K – 323 K) to examine the influence of CO

2 pressures on the hydrogenation of

1. In those runs, unfortunately, hydroformylation also took place or the overall conversion was small, and these attempts were not successful.

The dissolution of CO2 into the solvent phase would decrease the concentration of 1 (and 2) and H2 and this might reduce the rate of hydrogenation of both 1 and 2. However, the present results show that the conversion of 2 to 3 is not suppressed. For 2 as well, the dense CO2 molecules little affect the reactivity of 2 (suggested from FTIR results). The simple hydrogenation of 2 was tested with the same catalyst system at a H2 pressure of 3 MPa (in the absence of CO2); the conversion was found to be more than 90 % and 60 % at 423 K (used for hydrofomylation runs) and 393 K, respectively (the conversion was observed to decrease in the presence of CO2 for this hydrogenation of 2, due to the dilution effect). The hydrogenation of 2 to 3 is assumed to be faster than the hydrofomylation of 1 to 2. Under the hydroformylation conditions used, the hydroformylation of 1 is promoted with CO2 pressure; this is positive for promoting the subsequent hydrogenation of 2, which is against the negative dilution effect. As a result of the balance of these positive and negative effects the hydrogenation of 2 to 3 should not be suppressed with CO2 pressure, in contrast to that of 1 to 4 (the simple dilution effect only).

The effect of CO

2 and H

2 pressures on the hydroformylation and hydrogenation reactions also includes that of CO and H

2O formed via the reverse water gas shift reaction (RWGSR). As mentioned in 2.1., the RWGSR is assumed to go faster compared with the following hydroformylation with CO formed in the former reaction and the latter should determine the overall rate of hydroformylation of

1 with CO

2 and H

2 under the conditions used. The further detailed discussion on the pressure effects at molecular level should consider the roles of those intermediate and byproduct gases. The volume of NMP liquid phase little changes on the pressurization with CO

2 and H

2 (

Figure 4), and so the species of

1 and

2 are likely to exist mainly in the liquid phase. This should be confirmed by measurements of the solubility of these species in either NMP liquid phase or dense CO

2 gas phase.

In the present work a homogeneous catalyst of Ru

3(CO)

12 and LiCl was used, which were soluble and functioned in the solvent phase (NMP in the present case). For practical operation, the separation and recycling of a catalyst is an important aspect for hydroformylation and other reaction processes [

9,

18]. Recently Tominaga and Sasaki attempted to use a biphasic system of an organic solvent and an ionic liquid for hydroformylation using CO

2 and H

2[

19,

20]. They screened several couples of organic solvents and ionic liquids and showed that the hydrofomylation of 1-hexene proceeded and Ru complex catalysts were recyclable for some couples. Under the conditions, however, alcohol was selectively formed but no aldehyde was obtained. The heterogenization of catalytic reaction systems and the control of product selectivity are also interesting and challenging tasks for hydroformylation with CO

2 and H

2.