Exposure to Engineered Nanomaterials: Impact on DNA Repair Pathways

Abstract

:1. Introduction

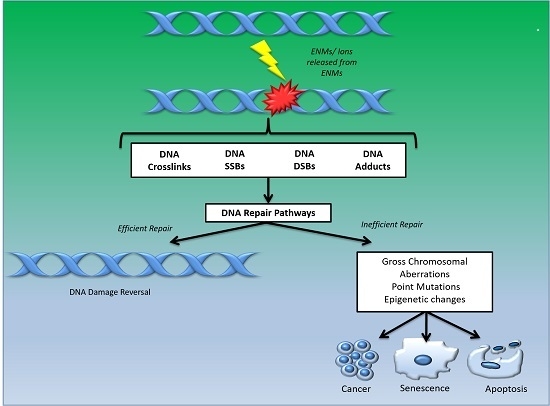

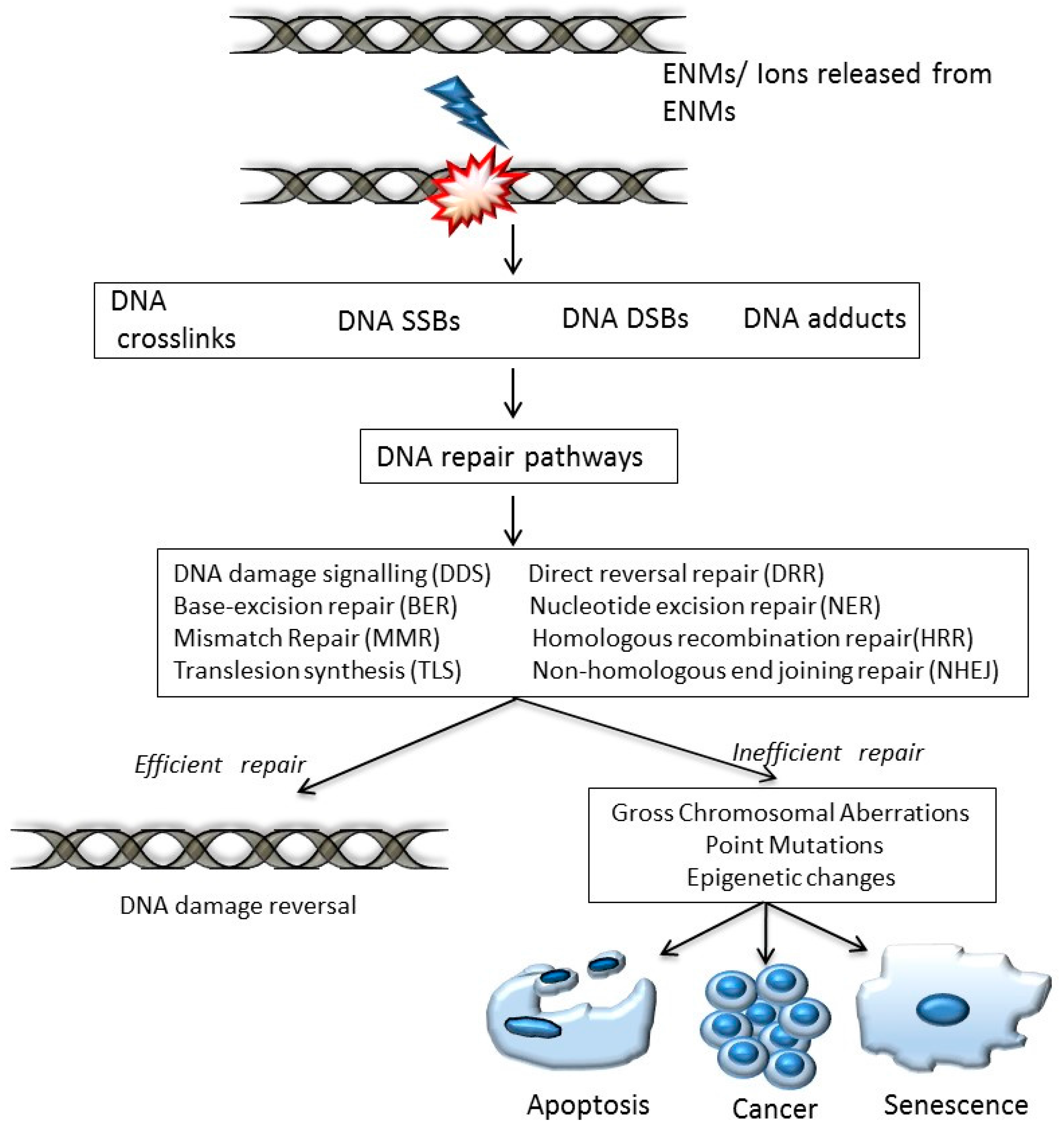

- DNA damage signalling (DDS): this pathway is induced in response to DNA damage caused by various agents including environmental, ENM and endogenous. DDS pathways are programmed to induce several cellular responses including checkpoint activity, triggering of apoptotic pathways and DNA repair [13].

- Direct reversal repair (DRR): reverses/eliminates the DNA damage caused by chemical reversal or modification by restoring the original nucleotide. It is also known as direct DNA damage reversal.

- Base-excision repair (BER): this repair mechanism is initiated by the excision of modified bases from DNA by DNA glycosylases. The length of the DNA that needs to undergo re-synthesis can be variable; thus, the pathway can be subdivided into short-path or long-path BER. Although various pathways are involved in this repair process, one of the most widely studied mechanisms that triggers the BER pathway is oxidatively induced damage. Since oxidative stress is one of the most common mechanisms of ENM-induced DNA damage, oxidatively induced DNA lesions are predominantly repaired by the BER pathway (see Table 1). The key enzymes involved in the BER process are DNA glycosylases, which remove damaged bases by cleavage of the N-glycosylic bonds (between the bases and deoxyribose moieties) of the nucleotide residues. The DNA glycosylase action is followed by an incision step, DNA synthesis, an excision step, and DNA ligation. Various metal oxide based ENMs, quantum dots and carbon nanomaterials have been implicated in activating the BER pathway (Table 1).

- Nucleotide excision repair (NER): is involved in removing bulky DNA adducts. The damage from the active strand of transcribed DNA and DNA damage elsewhere in the genome is removed in this pathway by transcription-coupled repair and global genome repair, respectively. Silver and cadmium based ENMs have been shown to interfere with the NER pathway (Table 1).

- Mismatch repair (MMR): this pathway is involved in post-replicational DNA repair that removes errors including mismatched nucleotides, insertions, deletions, etc.

- Homologous recombination repair (HRR): this pathway involves repair of DSBs using the homologous DNA strand as a template for re-synthesis.

- Non-homologous end joining repair (NHEJ): helps to ligate the DNA ends resulting from DSBs.

- Translesion synthesis (TLS): this pathway employs specialized polymerases that use damaged DNA as templates, to finish replication across lesions. Although the mechanism is error-prone, and cell survival may be associated with an increased risk of mutagenesis/carcinogenesis, it helps to prevent a stalled replication fork.

2. Activation/Up-Regulation of DNA Damage Signalling Pathways

3. Up-Regulation of DNA Repair Genes

4. Inactivation/Downregulation of DNA Repair Pathway Genes

5. Conclusions & Future Considerations

- Characterisation of induced DNA damage lesions: a given ENM may have a primary mechanism for the induction of DNA damage, which triggers the initiation of a specific repair pathway. For example, metal and metal oxide based ENMs tend to cause oxidatively induced DNA damage, which is mainly repaired via the BER pathway. Therefore, characterising the type of DNA damage is critically important in future studies, as it will enable predictive models to be developed that can be used to predict which types of ENMs might affect specific DNA repair pathways.

- Role of ions: inorganic NPs could via corrosion and dissolution release metal ions such as Cd2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, and Ag+ and hence influence the upregulation/downregulation (measured as excision activity) of various pathways. Additionally, metal ions released from ENMs have been shown to interact/bind with protein domains and amino acids of DNA repair proteins (e.g., zinc finger structures contained in the DNA repair protein, XPA) resulting in distorted protein structure and inefficient DNA repair activity [40]. Therefore, a thorough physicochemical characterisation of ENMs is imperative, to discriminate between the actual causative factor (ENM vs. metal ions), as the impact of ENMs on DNA repair pathway may be strongly associated with the presence of metal(s) either in their composition, or as undesirable impurities.

- Dose-dependent DNA damage response: presently, the doses of ENMs administered in in vitro studies/test species to generate dose-response analysis may not mimic a potential human exposure level. This is because concentration-dependent activation of genes/pathways as well as transition in gene changes can be highly dose dependent. Therefore, dose ranges that are relevant to true exposure levels of ENMs need to be included when studying DNA damage responses pertaining to repair pathways. However, ENM exposure assessment currently presents a technical challenge and more work is needed to evaluate emissions of ENMs into the environment [41]. For example, it will be necessary to perform more thorough background measurements at workplaces to determine accurate occupational exposure levels, to develop appropriate metrics for ENM exposure assessments and to validate personal air samplers.

- Method/technique: various techniques and methods with different endpoints are utilized for evaluating DNA damage repair and/or DNA damage responses, e.g., Western blots for translational changes/modifications and/or phosphorylation events; RT-PCR for transcriptional alterations; excision or incision assays for DNA repair enzyme activity; mass spectrometry methods for measuring adduct or lesion formation and multiplexed excision/synthesis assays for DNA repair enzyme inhibition activity [31]. Each method has its own sensitivity, specificity and endpoints, which makes it challenging to compare results across different studies. Hence, to enable an appropriate intra-laboratory/interlaboratory comparison of DNA damage repair responses, statistically appropriate analysis on normalised data must be performed in order to identify reproducible upregulation or downregulation of ENM-induced DNA repair responses.

- Tissue specific detection /expression: different tissues and cell types (including primary cells, normal/cancer cell lines) exhibit varying DNA repair responses, which may correlate with the degree of DNA damage and susceptibility following exposure to some ENMs. Hence, it is imperative to measure the levels and activity of DNA repair genes and proteins, respectively, in all relevant cells, tissues or organs of interest as their expression and responses are largely “site-specific”.

- Effect of acute vs. chronic exposure of ENMs: the type of exposure may affect the severity of the DNA damage and the resultant activation of specific DNA repair pathway(s). The human population may be exposed to natural, environmental or ENMs in a cumulative manner [42]. On the other hand, occupational, lifestyle or behaviour-related exposure to various nano-entities may induce acute responses [8,43]. Therefore, it is important to understand how various kinds of exposure scenarios dictate not only DNA damage, but also trigger specific repair pathways.

- Effect of potential ENM artefacts on the interpretation of DNA damage repair or DNA damage response: as described in previous reports, the solution state physico-chemical properties of ENMs are not like the solution state physicochemical properties of chemicals [44]. Depending upon the category of ENMs under investigation, ENMs are prone to disparate rates of dissolution, aggregation/agglomeration phenomena, nutrient depletion and other behaviours that can potentially result in false-positive and/or false-negative responses in DNA damage repair and DNA damage response assays. These types of artefactual effects have been observed in many types of nanotoxicity [45] and nanoecotoxicity [44], but can be avoided by including appropriate experimental controls in the assays and having a thorough understanding of the assay variability parameters.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

NIST Disclaimer

References

- European Commission Recommendation on the Definition of Nanomaterial Text with EEA Relevance, 2011/696/EU. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reco/2011/696/oj (accessed on 30 June 2017).

- Arora, S.; Rajwade, J.M.; Paknikar, K.M. Nanotoxicology and in vitro studies: The need of the hour. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2012, 258, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Manshian, B.; Jenkins, G.J.; Griffiths, S.M.; Williams, P.M.; Maffeis, T.G.; Wright, C.J.; Doak, S.H. NanoGenotoxicology: The DNA damaging potential of engineered nanomaterials. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 3891–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, S.J.; Clift, M.J.; Singh, N.; de Mallia, J.O.; Burgum, M.; Wills, J.W.; Wilkinson, T.S.; Jenkins, G.J.; Doak, S.H. Critical review of the current and future challenges associated with advanced in vitro systems towards the study of nanoparticle (secondary) genotoxicity. Mutagenesis 2017, 32, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biola-Clier, M.; Beal, D.; Caillat, S.; Libert, S.; Armand, L.; Herlin-Boime, N.; Sauvaigo, S.; Douki, T.; Carriere, M. Comparison of the DNA damage response in BEAS-2B and A549 cells exposed to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Mutagenesis 2017, 32, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Jenkins, G.J.; Nelson, B.C.; Marquis, B.J.; Maffeis, T.G.; Brown, A.P.; Williams, P.M.; Wright, C.J.; Doak, S.H. The role of iron redox state in the genotoxicity of ultrafine superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broustas, C.G.; Lieberman, H.B. DNA damage response genes and the development of cancer metastasis. Radiat. Res. 2014, 181, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langie, S.A.; Koppen, G.; Desaulniers, D.; Al-Mulla, F.; Al-Temaimi, R.; Amedei, A.; Azqueta, A.; Bisson, W.H.; Brown, D.G.; Brunborg, G.; et al. Causes of genome instability: The effect of low dose chemical exposures in modern society. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36 (Suppl. S1), S61–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guengerich, F.P. Common and uncommon cytochrome P450 reactions related to metabolism and chemical toxicity. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2001, 14, 611–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, S.R.; Ordaz, J.; Lo, C.L.; Damayanti, N.P.; Zhou, F.; Irudayaraj, J. ZnO nanoparticles induced reactive oxygen species promotes multimodal cyto- and epigenetic toxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 156, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Villarreal, J.; Rivas-Armendariz, D.I.; Perez-Vertti, R.D.A.; Calderon, E.O.; Garcia-Garza, R.; Betancourt-Martinez, N.D.; Serrano-Gallardo, L.B.; Moran-Martinez, J. Relationship between lymphocyte DNA fragmentation and dose of iron oxide (Fe2O3) and silicon oxide (SiO2) nanoparticles. Genet. Mol. Res. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanowska, K.; Krwawicz, J.; Papaj, G.; Kosinski, J.; Poleszak, K.; Lesiak, J.; Osinska, E.; Rother, K.; Bujnicki, J.M. REPAIRtoire—A database of DNA repair pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D788–D792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, R.Y.; Chastain, P.D.; Nikolaishvili-Feinberg, N.; Smeester, L.; Kaufmann, W.K.; Fry, R.C. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles activate the ATM-Chk2 DNA damage response in human dermal fibroblasts. Nanotoxicology 2013, 7, 1111–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asharani, P.; Sethu, S.; Lim, H.K.; Balaji, G.; Valiyaveettil, S.; Hande, M.P. Differential regulation of intracellular factors mediating cell cycle, DNA Repair and inflammation following exposure to silver nanoparticles in human cells. Genome Integr. 2012, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovvuru, P.; Mancilla, P.E.; Shirode, A.B.; Murray, T.M.; Begley, T.J.; Reliene, R. Oral ingestion of silver nanoparticles induces genomic instability and DNA damage in multiple tissues. Nanotoxicology 2015, 9, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asare, N.; Duale, N.; Slagsvold, H.H.; Lindeman, B.; Olsen, A.K.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J.; Meczynska-Wielgosz, S.; Kruszewski, M.; Brunborg, G.; Instanes, C. Genotoxicity and gene expression modulation of silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in mice. Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satapathy, S.R.; Siddharth, S.; Das, D.; Nayak, A.; Kundu, C.N. Enhancement of cytotoxicity and inhibition of angiogenesis in oral cancer stem cells by a hybrid nanoparticle of bioactive quinacrine and silver: Implication of base excision repair cascade. Mol. Pharm. 2015, 12, 4011–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Berlo, D.; Hullmann, M.; Wessels, A.; Scherbart, A.M.; Cassee, F.R.; Gerlofs-Nijland, M.E.; Albrecht, C.; Schins, R.P. Investigation of the effects of short-term inhalation of carbon nanoparticles on brains and lungs of c57bl/6j and p47Phox−/− mice. Neurotoxicology 2014, 43, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Cai, Q.; Chibli, H.; Allagadda, V.; Nadeau, J.L.; Mayer, G.D. Cadmium sulfate and CdTe-quantum dots alter DNA repair in zebrafish (Danio rerio) liver cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 272, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Wu, Y.; Ryan, C.N.; Yu, S.; Qin, G.; Edwards, D.S.; Mayer, G.D. Distinct Expression Profiles of Stress Defense and DNA Repair Genes in Daphnia Pulex Exposed to Cadmium, Zinc, and Quantum Dots. Chemosphere 2015, 120, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahamed, M.; Siddiqui, M.A.; Akhtar, M.J.; Ahmad, I.; Pant, A.B.; Alhadlaq, H.A. Genotoxic potential of copper oxide nanoparticles in human lung epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 396, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, M.; Bello, D.; Pal, A.K.; Cohen, J.M.; Woskie, S.; Gassert, T.; Lan, J.; Gu, A.Z.; Demokritou, P.; Gaines, P. Evaluation of cytotoxic, genotoxic and inflammatory responses of nanoparticles from photocopiers in three human cell lines. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Said, K.S.; Ali, E.M.; Kanehira, K.; Taniguchi, A. Molecular mechanism of DNA damage induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in toll-like receptor 3 or 4 expressing human hepatocarcinoma cell lines. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2014, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanot-Roy, M.; Tubeuf, E.; Guilbert, A.; Bado-Nilles, A.; Vigneron, P.; Trouiller, B.; Braun, A.; Lacroix, G. Oxidative stress pathways involved in cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles on cells constitutive of alveolo-capillary barrier in vitro. Toxicol. In Vitro 2016, 33, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, R.; Das, I.; Mehta, R.K.; Sahu, R.; Sonawane, A. Zinc-oxide nanoparticles exhibit genotoxic, clastogenic, cytotoxic and actin depolymerization effects by inducing oxidative stress responses in macrophages and adult mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2016, 150, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chastain, P.D., II; Heffernan, T.P.; Nevis, K.R.; Lin, L.; Kaufmann, W.K.; Kaufman, D.G.; Cordeiro-Stone, M. Checkpoint regulation of replication dynamics in UV-irradiated human Cells. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2160–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kansara, K.; Patel, P.; Shah, D.; Shukla, R.K.; Singh, S.; Kumar, A.; Dhawan, A. TiO2 nanoparticles induce DNA double strand breaks and cell cycle arrest in human alveolar cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2015, 56, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahm, S.H.; Park, J.H.; Ko, S.I.; Lee, Y.R.; Chung, I.S.; Chung, J.H.; Kang, L.W.; Han, Y.S. Knock-down of human MutY homolog (hMYH) decreases phosphorylation of checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1) induced by hydroxyurea and UV treatment. BMB Rep. 2011, 44, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahm, S.H.; Chung, J.H.; Agustina, L.; Han, S.H.; Yoon, I.S.; Park, J.H.; Kang, L.W.; Park, J.W.; Na, J.J.; Han, Y.S. Human MutY homolog induces apoptosis in etoposide-treated HEK293 cells. Oncol. Lett. 2012, 4, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oka, S.; Ohno, M.; Tsuchimoto, D.; Sakumi, K.; Furuichi, M.; Nakabeppu, Y. Two distinct pathways of cell death triggered by oxidative damage to nuclear and mitochondrial DNAs. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millau, J.F.; Raffin, A.L.; Caillat, S.; Claudet, C.; Arras, G.; Ugolin, N.; Douki, T.; Ravanat, J.L.; Breton, J.; Oddos, T.; et al. A microarray to measure repair of damaged plasmids by cell lysates. Lab Chip 2008, 8, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Mondal, T.; Bhowmick, A.K.; Das, P. Impeded repair of abasic site damaged lesions in DNA adsorbed over functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotube and graphene oxide. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2016, 803, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, A.; Speit, G. Effect of arsenic and cadmium on the persistence of mutagen-induced DNA lesions in human cells. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 1996, 27, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.D.; Davis, G.F.; Lachmann, P.J. Inhibition by metals of X-ray and ultraviolet-induced DNA repair in human cells. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1989, 21, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candeias, S.; Pons, B.; Viau, M.; Caillat, S.; Sauvaigo, S. Direct inhibition of excision/synthesis DNA repair activities by cadmium: Analysis on dedicated biochips. Mutat. Res. 2010, 694, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeill, D.R.; Narayana, A.; Wong, H.K.; Wilson, D.M., III. Inhibition of Ape1 nuclease activity by lead, iron, and cadmium. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004, 112, 799–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jugan, M.L.; Barillet, S.; Simon-Deckers, A.; Herlin-Boime, N.; Sauvaigo, S.; Douki, T.; Carriere, M. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles exhibit genotoxicity and impair DNA repair activity in A549 cells. Nanotoxicology 2012, 6, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebel, T.; Foth, H.; Damm, G.; Freyberger, A.; Kramer, P.J.; Lilienblum, W.; Rohl, C.; Schupp, T.; Weiss, C.; Wollin, K.M.; et al. Manufactured nanomaterials: Categorization and approaches to hazard assessment. Arch. Toxicol. 2014, 88, 2191–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R. It’s not just about nanotoxicology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carriere, M.; Sauvaigo, S.; Douki, T.; Ravanat, J.L. Impact of nanoparticles on DNA repair processes: Current knowledge and working hypotheses. Mutagenesis 2017, 32, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Moon, M.C.; Lee, J.Y.; Yu, I.J. Challenges and perspectives of nanoparticle exposure assessment. Toxicol. Res. 2010, 26, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA. Nanomaterial Case Study: Nanoscale Silver in Disinfectant Spray. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/risk/recordisplay.cfm?deid=241665 (Accessed on 9 March 2017).

- Rim, K.T.; Song, S.W.; Kim, H.Y. Oxidative DNA damage from nanoparticle exposure and its application to workers’ health: A literature review. Saf. Health Work. 2013, 4, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, E.J.; Henry, T.B.; Zhao, J.; MacCuspie, R.I.; Kirschling, T.L.; Dobrovolskaia, M.A.; Hackley, V.; Xing, B.S.; White, J.C. Identification and avoidance of potential artifacts and misinterpretations in nanomaterial ecotoxicity measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4226–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkilany, A.M.; Mahmoud, N.N.; Hashemi, F.; Hajipour, M.J.; Farvadi, F.; Mahmoudi, M. Misinterpretation in nanotoxicology: A personal perspective. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2016, 29, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Analysis Technique Applied | Cell/Tissue Used | NP | DNA Repair Pathway and Its Corresponding Component Involved | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) | Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ) | DNA Damage Signalling (DDS) | Base Excision Repair (BER) | Nucleotide Excision Repair (NER) | Mismatch Repair (MMR) | ||||

| AshaRani et al., 2012 [14] | mRNA and array hybridisation RT-PCR | Human lung fibroblast, IMR 90 | AgNPs | ↓ APEX1, MUTYH MBD4 OGG1 | |||||

| ↓ PMS1 MSH2 | |||||||||

| ↓ BRCA1 | |||||||||

| Kovvuru et al., 2014 [15] | DNA repair RT2 Profiler PCR array | Liver | AgNPs | ↓ APEX2 NEIL3 NEIL1 PARP1 NTHL1 MUTYH RPA1 XRCC1 | |||||

| ↑ TDG CCNO PARP2 UNG | |||||||||

| ↓ RAD23B ERCC8 XPC LIG1 RAD23A RPA1 | |||||||||

| ↓ RAD51/1 RAD51 | |||||||||

| ↑ RAD51C RAD52 | |||||||||

| Asare et al., 2015 [16] | PCR | Lung tissue | AgNPs | ↑ RAD51 | |||||

| ↑ ATM | |||||||||

| Satapathy et al., 2014 [17] | In Vivo Base Excision Repair (BER) Assay | Oral squamous cell carcinoma | QAgNPs | ↓ LIG1 FEN1 POLB POLD1 POLE | |||||

| Van Berlo et al., 2010 [18] | mRNA expression | Lung tissue | Carbon | ↑ OGG1 APEX1 | |||||

| Tang et al., 2013 [19] | RT-PCR | Daphnia pulex | CdSO4 or CdTeQDs | ↑ Ku80 | |||||

| ↑ OGG1 | |||||||||

| ↑ XPC XPA | |||||||||

| Tang et al., 2015 [20] | RT-PCR | Daphnia pulex | CdTe/ZnS | ↑ OGG1 | |||||

| ↑ XPA XPC | |||||||||

| Ahamed et al., 2010 [21] | Western blotting | Human pulmonary epithelial cells (A549) | CuO | ↑ RAD51 | |||||

| ↑ MSH2 | |||||||||

| Khatri et al., 2013 [22] | RT-PCR | THP-1, Primary human nasal, Small airway epithelial | ENMs emitted from photocopiers | ↑ RAD51 | |||||

| ↑ Ku70 | |||||||||

| Prasad et al., 2013 [13] | Western blot (phosphorylation) | Human dermal fibroblasts | TiO2 | ↑ Activation of ATM/Chk2 DNA damage signalling pathway | |||||

| El-said et al., 2014 [23] | RT-PCR | HepG2 | TiO2 | ↑ APEX1 MBD4 | |||||

| ↑ ATM | |||||||||

| Hanot-Roy et al., 2014 [24] | Western blot (phosphorylation) | Alveolar macrophages (THP-1), Epithelial cells (A549), Human Pulmonary Endothelial Cells (HPMEC-ST1.6R cells) | TiO2 | ↑ ATM ATR | |||||

| Pati et al., 2016 [25] | Western blot | Macrophages | Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) | ↓ POLB FEN1 | |||||

| Enzyme/ Protein | Function |

|---|---|

| DDS Pathway | |

| ATM (ataxia-telangiectasia mutated) | Cell cycle checkpoint kinase protein, which belongs to the PI3/PI4- kinase family. Serves as a DNA damage sensor and regulator of a wide variety of downstream proteins, including, 1) Tumour suppressor protein p53 and 2) Serine/threonine protein kinase that activates checkpoint signalling upon double strand breaks (DSBs), apoptosis, and genotoxic stresses. |

| ATR Rad3-related kinase | PI3 kinase-related kinase family member (like ATM), which phosphorylates multiple substrates on serine/ threonine residues (that are followed by a glutamine) in response to DNA damage or replication blocks. Causes cell cycle delay, in part, by phosphorylating checkpoint kinase (CHK)1, CHK2, and p53. |

| CHK1 and CHK2 (Checkpoint kinase 1 and 2) | Downstream protein kinases of ATM/ATR, which play an important role in DNA damage checkpoint control. |

| BER Pathway | |

| APEX1 (Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1) | Multifunctional DNA repair enzyme, apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1/redox factor-1 (APE1/Ref-1) responsible for abasic site cleavage activity. Plays a critical role in the DNA base excision repair (BER) pathway and in the redox regulation of transcriptional factors. Activated/ induced by oxidative DNA damage. Localisation signals, post-translational modifications and dynamic regulation determines the localisation of APE protein in the nucleus with subcellular localization in the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and cytoplasm. |

| APEX2 (Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 2) | AP endonuclease 2 is characterized by a weak AP endonuclease activity, 3′-phosphodiesterase activity and 3′- to 5′-exonuclease activity. Involved in removal of mismatched 3′-nucleotides from DNA and ATR-Chk1 checkpoint signalling in response to oxidative stress. |

| (POLB) DNA polymerase β | Contributes to DNA synthesis and deoxyribose-phosphate removal. |

| (FEN1) Flap endonuclease 1 | Possesses 5′–3′ exonuclease activity and cleaves 5′ overhanging “flap structures” in DNA replication and repair. |

| LIG1 (Ligase 1) | Seals SSB ends. |

| MBD4 (methyl-CpG binding domain protein 4) | Belongs to a family of nuclear proteins that possess a methyl-CpG binding domain (MBD). These proteins bind specifically to methylated DNA, possess DNA N-glycosylase activity and can remove uracil or 5-fluorouracil in G:U mismatches. |

| MUTYH (mutY DNA glycosylase) | Serves as DNA glycosylase (excises adenine mispaired with 8-oxoguanine). Maintains chromosome stability by inducing ATR-mediated checkpoint activation, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. |

| NEIL1, NEIL3 (Nei-like 1; Nei-like 3) | Generate apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites and/or SSBs with blocked ends. |

| NTHL1 | Serve as oxidized base-specific DNA glycosylases that remove oxidized and/or mismatched DNA bases. |

| OGG1 (8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase) | Excises and repairs oxidatively damaged guanine bases in DNA, which occur as a result of exposure to ROS. |

| PCNA (Proliferating cell nuclear antigen) | Co-factor for DNA polymerase and essential for DNA synthesis and repair. |

| PARP1 (Poly ADP ribose polymerase) | PARP1—serves as sensor of SSBs. |

| XRCC1 (X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1) | XRCC1—serves as a scaffold for recruiting and activating BER proteins. |

| NER Pathway | |

| RPA1 (replication protein A1) | Largest subunit of the replication protein A (RPA), the heterotrimeric single-stranded DNA-binding protein involved in replication, repair, recombination and DNA damage check point activation. |

| XPC (xeroderma pigmentosum group C protein) | Recognizes bulky DNA adducts. Pairs up with RAD23 and helps in the assembly of the other core proteins involved in NER pathway progression. |

| XPA (xeroderma pigmentosum group A protein) | Attaches to damaged DNA, interacts along with other proteins in the NER pathway to unwind, excise and replace the damaged DNA. |

| HRR Pathway | |

| BRCA1/ BRCA2 (breast cancer type 1 and type 2 susceptibility proteins) | BRCA1 and BRCA2 are coded by human tumour suppressor genes that are involved in DNA damage repair, cell cycle progression, transcription, ubiquitination and apoptosis. Aberrant proteins coded by mutated genes are found in hereditary breast and ovarian cancers; activation of various kinases in response to DNA-damage have been shown to phosphorylate sites on BRC1 and BRC2 in a cell cycle-dependent manner. |

| RAD51 | Involved in the homologous recombination and repair of double strand DNA breaks. |

| NHEJ Pathway | |

| Ku | Ku, a heterodimer of two related proteins, Ku70 and Ku80, is involved in DSB repair and V(D)J recombination. |

| LIG4 (Ligase 4) | LIG4 is the DNA ligase required for, and specific to, c-NHEJ. It catalyzes the same ATP-dependent transfer of phosphate bonds that results in strand ligation in all eukaryotic DNA repair. LIG4 is the only ligase with the mechanistic flexibility to ligate one strand independently of another or to ligate incompatible DSB ends as well as gaps of several nucleotides. |

| XRCC4 (X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1) | XRCC4 is a non-enzymatic protein that is required for the conformational stability and functioning levels of LIG4. XRCC4 interacts with LIG4 facilitated by carboxy-terminal repeats at the LIG4 carboxyl terminus, resulting in a coiled-coil like conformation. Most of the enzymatic domain of LIG binds to and interacts with XRCC4, except for the small region implicated in DNA binding. |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, N.; Nelson, B.C.; Scanlan, L.D.; Coskun, E.; Jaruga, P.; Doak, S.H. Exposure to Engineered Nanomaterials: Impact on DNA Repair Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071515

Singh N, Nelson BC, Scanlan LD, Coskun E, Jaruga P, Doak SH. Exposure to Engineered Nanomaterials: Impact on DNA Repair Pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(7):1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071515

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Neenu, Bryant C. Nelson, Leona D. Scanlan, Erdem Coskun, Pawel Jaruga, and Shareen H. Doak. 2017. "Exposure to Engineered Nanomaterials: Impact on DNA Repair Pathways" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 7: 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18071515