Impact of Labile Zinc on Heart Function: From Physiology to Pathophysiology

Abstract

:1. Introduction

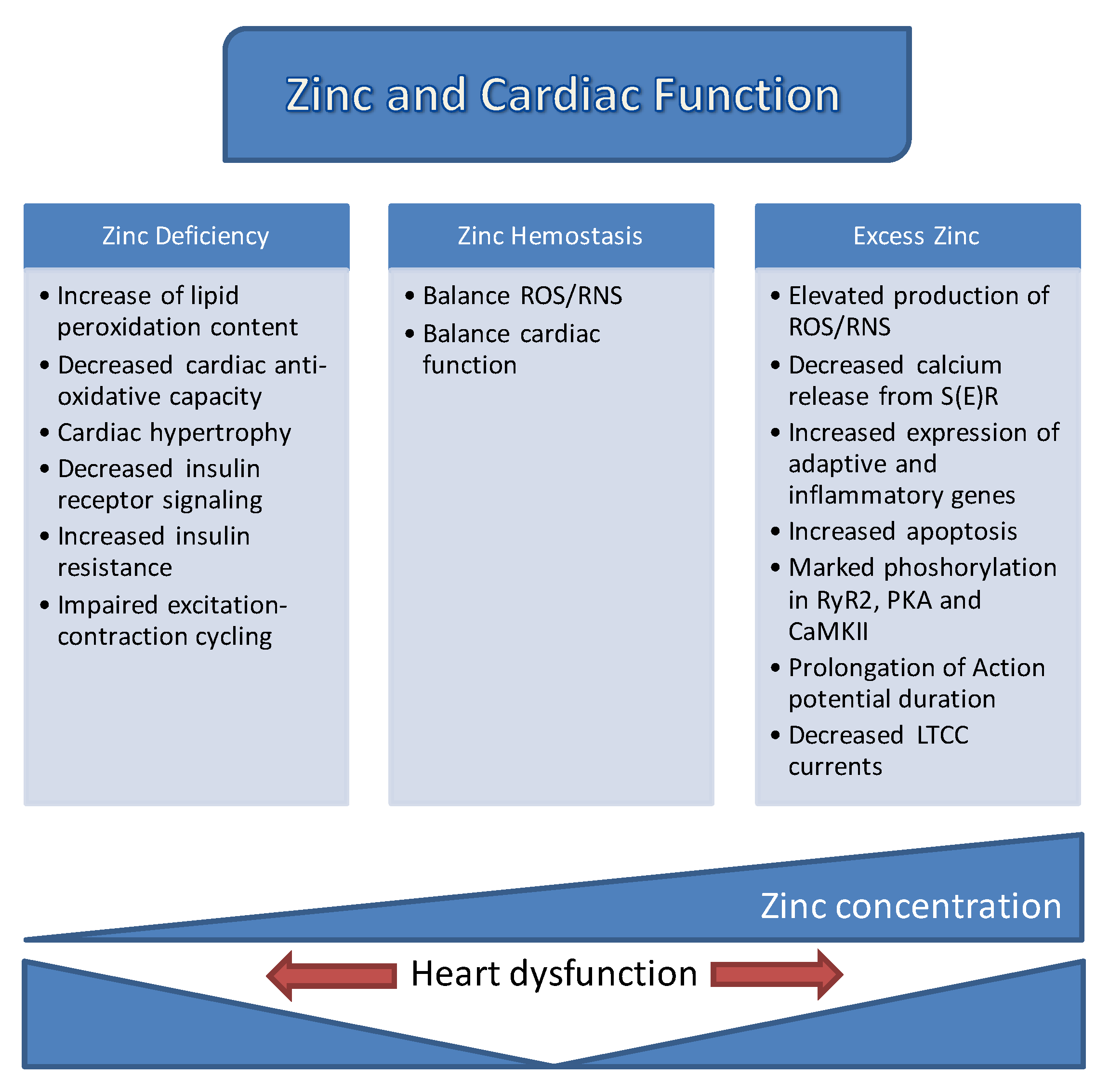

2. Role of Zinc in Human Health

3. Labile Zn2+ in Cardiac Physiology and Pathology

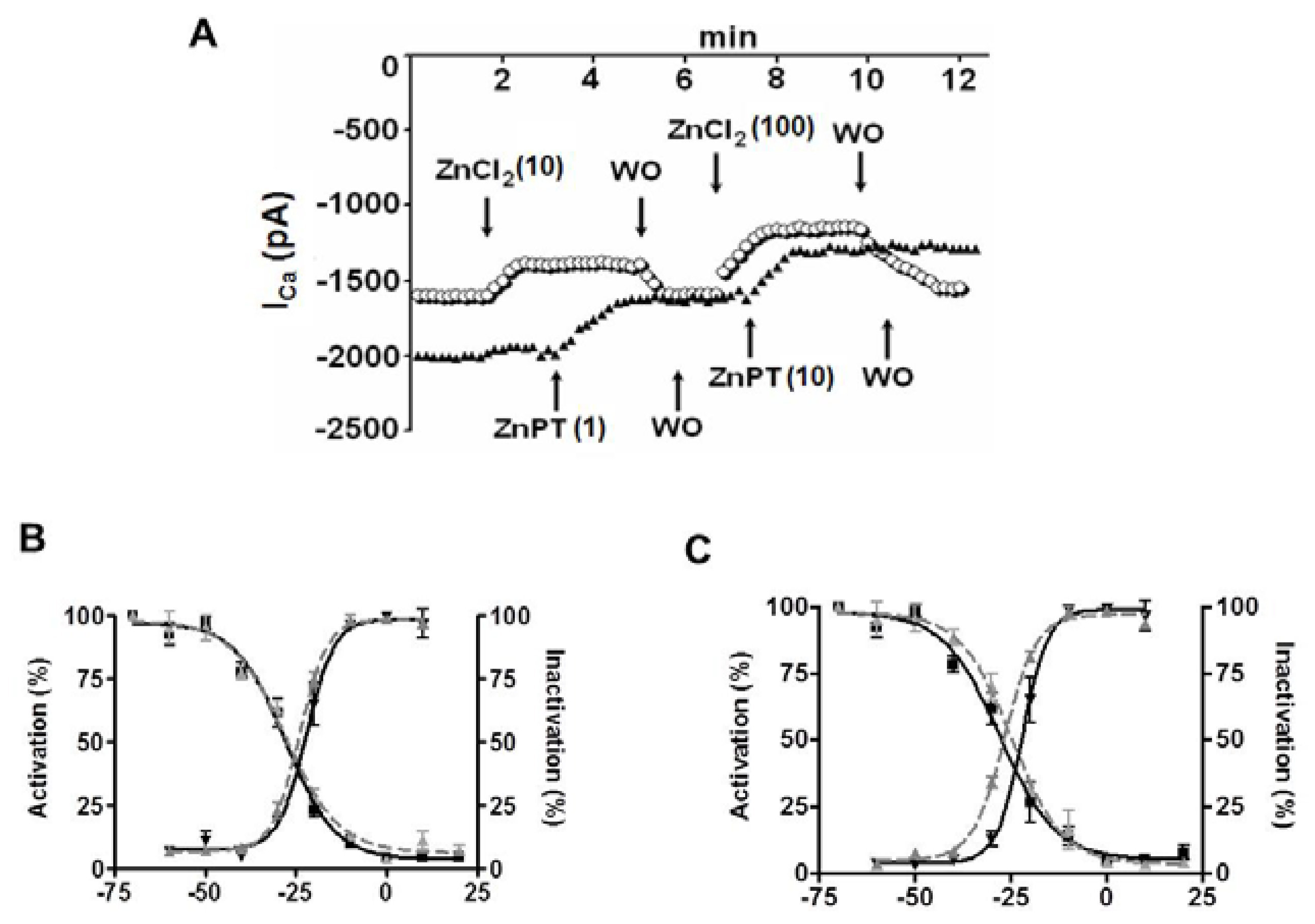

4. Role of Cellular Labile Zn2+ in Electrical Properties of Cardiomyocytes

5. Labile Zn2+ Pools in Cardiomyocytes

6. Zn2+ Transporters in Cardiomyocytes

7. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oteiza, P.I. Zinc and the modulation of redox homeostasis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1748–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallee, B.L.; Falchuk, K.H. The biochemical basis of Zinc physiology. Physiol. Rev. 1993, 73, 79–118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drinker, H.S. Concerning Modern Corporate Mortgages. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. Am. Law 1926, 74, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M.; Hirano, T. Intracellular Zinc homeostasis and Zinc signaling. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maret, W. Zinc and human disease. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2013, 13, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Coudray, C.; Charlon, V.; de Leiris, J.; Favier, A. Effect of Zinc deficiency on lipid peroxidation status and infarct size in rat hearts. Int. J. Cardiol. 1993, 41, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret, W. Zinc biochemistry: From a single Zinc enzyme to a key element of life. Adv. Nutr. (Bethesda, Md.) 2013, 4, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, B.; Fliss, H.; Desilets, M. Oxidants increase intracellular free Zn2+ concentration in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, H2095–H2106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tuncay, E.; Bilginoglu, A.; Sozmen, N.N.; Zeydanli, E.N.; Ugur, M.; Vassort, G.; Turan, B. Intracellular free Zinc during cardiac excitation-contraction cycle: Calcium and redox dependencies. Cardiovasc. Res. 2011, 89, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncay, E.; Turan, B. Intracellular Zn2+ increase in cardiomyocytes induces both electrical and mechanical dysfunction in heart via endogenous generation of reactive nitrogen species. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2016, 169, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabosseau, P.; Tuncay, E.; Meur, G.; Bellomo, E.A.; Hessels, A.; Hughes, S.; Johnson, P.R.; Bugliani, M.; Marchetti, P.; Turan, B.; et al. Mitochondrial and ER-targeted eCALWY probes reveal high levels of free Zn2+. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 2111–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, A.J.; Bhattacharya, S.K. Excessive intracellular Zinc accumulation in cardiac and skeletal muscles of dystrophic hamsters. Exp. Neurol. 1987, 95, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J.; Rosenkranz, E.; Overbeck, S.; Warmuth, S.; Mocchegiani, E.; Giacconi, R.; Weiskirchen, R.; Karges, W.; Rink, L. Disturbed Zinc homeostasis in diabetic patients by in vitro and in vivo analysis of insulinomimetic activity of Zinc. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atar, D.; Backx, P.H.; Appel, M.M.; Gao, W.D.; Marban, E. Excitation-transcription coupling mediated by Zinc influx through voltage-dependent Calcium channels. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 2473–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maret, W. Metals on the move: Zinc ions in cellular regulation and in the coordination dynamics of Zinc proteins. Biometals 2011, 24, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle, P.; Philcox, J.C.; Carey, L.C.; Rofe, A.M. Metallothionein: The multipurpose protein. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2002, 59, 627–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennigar, S.R.; Kelleher, S.L. Zinc networks: The cell-specific compartmentalization of Zinc for specialized functions. Biol. Chem. 2012, 393, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T. An overview of a wide range of functions of ZnT and ZIP Zinc transporters in the secretory pathway. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T.; Tsuji, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Itsumura, N. The physiological, biochemical, and molecular roles of Zinc transporters in Zinc homeostasis and metabolism. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 749–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T.; Yamaguchi-Iwai, Y.; Sasaki, R.; Nagao, M. Overview of mammalian Zinc transporters. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2004, 61, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eide, D.J. The SLC39 family of metal ion transporters. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2004, 447, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichten, L.A.; Cousins, R.J. Mammalian Zinc transporters: Nutritional and physiologic regulation. Ann. Rev. Nutr. 2009, 29, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukada, T.; Kambe, T. Molecular and genetic features of zinc transporters in physiology and pathogenesis. Met. Integr. Biomet. Sci. 2011, 3, 662–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, W.R.; Elvehjem, C.A.; Hart, E.B. Zinc in the nutrition of the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 1934, 107, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.S.; Miale, A., Jr.; Farid, Z.; Sandstead, H.H.; Schulert, A.R. Zinc metabolism in patients with the syndrome of iron deficiency anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, dwarfism, and hypognadism. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1963, 61, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Buamah, P.K.; Russell, M.; Bates, G.; Ward, A.M.; Skillen, A.W. Maternal zinc status: A determination of central nervous system malformation. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1984, 91, 788–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.S. Impact of the discovery of human Zinc deficiency on health. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. Organ Soc. Miner. Trace Elements (GMS) 2014, 28, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.P.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Tong, Y.P.; Xue, Y.F.; Liu, D.Y.; Zhang, W.; Deng, Y.; Meng, Q.F.; Yue, S.C.; Yan, P.; et al. Harvesting more grain Zinc of wheat for human health. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, T.; Takeda, T.A.; Takagishi, T.; Fukue, K.; Kambe, T.; Fukada, T. Physiological roles of Zinc transporters: Molecular and genetic importance in Zinc homeostasis. J. Physiol. Sci. 2017, 67, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arquilla, E.R.; Packer, S.; Tarmas, W.; Miyamoto, S. The effect of Zinc on insulin metabolism. Endocrinology 1978, 103, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.S. Zinc deficiency and effects of Zinc supplementation on sickle cell anemia subjects. Progress Clin. Biol. Res. 1981, 55, 99–122. [Google Scholar]

- Savin, J.A. Skin disease: The link with Zinc. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1984, 289, 1476–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmer, K.; Thompson, R.P. Maternal Zinc and intrauterine growth retardation. Clin. Sci. 1985, 68, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, L.H. Zinc and micronutrient supplements for children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 495s–498s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Raulin, J. Chemical studies on vegetation. J. Ann. Sci. Nat. 1869, 11, 93–99. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Fosmire, G.J. Zinc toxicity. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1990, 51, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, M.M.; Schoenheit, J.E.; Weaver, A.D. Pretreatment and heavy metal LD50 values. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1979, 49, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, P.J.; Grubb, B.R. Effects of a Zinc-deficient diet on tissue Zinc concentrations in rabbits. J. Anim. Sci. 1991, 69, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, A.S.; Walker, D.G.; Dehgani, A.; Halsted, J.A. Cirrhosis of the liver in Iran. Arch. Intern. Med. 1961, 108, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncay, E.; Bitirim, V.C.; Durak, A.; Carrat, G.R.J.; Taylor, K.M.; Rutter, G.A.; Turan, B. Hyperglycemia-induced changes in ZIP7 and ZnT7 expression cause Zn2+ Release From the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum and mediate ER stress in the heart. Diabetes 2017, 66, 1346–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bould, C.; Nicholas, D.J.; Tolhurst, J.A.H.; Wallace, T.; Potter, J.M.S. Zinc deficiency of fruit trees in Britain. Nature 1949, 164, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelmach, I.; Grzelewski, T.; Bobrowska-Korzeniowska, M.; Kopka, M.; Majak, P.; Jerzynska, J.; Stelmach, W.; Polanska, K.; Sobala, W.; Gromadzinska, J.; et al. The role of Zinc, Copper, plasma glutathione peroxidase enzyme, and vitamins in the development of allergic diseases in early childhood: The Polish mother and child cohort study. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2014, 35, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markiewicz-Zukowska, R.; Gutowska, A.; Borawska, M.H. Serum Zinc concentrations correlate with mental and physical status of nursing home residents. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.K.; Lee, S.H.; Han, K.; Kang, B.; Lee, S.Y.; Yoon, K.H.; Kwon, H.S.; Park, Y.M. Lower serum Zinc levels are associated with unhealthy metabolic status in normal-weight adults: The 2010 korea national health and nutrition examination survey. Diabetes Metab. 2015, 41, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yary, T.; Virtanen, J.K.; Ruusunen, A.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Voutilainen, S. Serum Zinc and risk of type 2 diabetes incidence in men: The kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. Organ Soc. Miner. Trace Elements (GMS) 2016, 33, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, A.F.; Simic, A.; Asvold, B.O.; Romundstad, P.R.; Midthjell, K.; Syversen, T.; Flaten, T.P. Trace elements in early phase type 2 diabetes mellitus-A population-based study. The HUNT study in Norway. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. Organ Soc. Miner. Trace Elements (GMS) 2017, 40, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simic, A.; Hansen, A.F.; Asvold, B.O.; Romundstad, P.R.; Midthjell, K.; Syversen, T.; Flaten, T.P. Trace element status in patients with type 2 diabetes in Norway: The HUNT3 Survey. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. Organ Soc. Miner. Trace Elements (GMS) 2017, 41, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, S.S.; Campa, A.; Li, Y.; Fleetwood, C.; Stewart, T.; Ramamoorthy, V.; Baum, M.K. Low plasma Zinc is associated with higher mitochondrial oxidative stress and faster liver fibrosis development in the miami adult studies in HIV cohort. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunutsor, S.K.; Laukkanen, J.A. Serum Zinc concentrations and incident hypertension: New findings from a population-based cohort study. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.M.; Wolf, P.; Hauner, H.; Skurk, T. Effect of a fermented dietary supplement containing chromium and Zinc on metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind cross-over study. Food Nutr. Res. 2016, 60, 30298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncay, E.; Okatan, E.N.; Vassort, G.; Turan, B. β-blocker timolol prevents arrhythmogenic Ca2+ release and normalizes Ca2+ and Zn2+ dyshomeostasis in hyperglycemic rat heart. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraker, P.J.; Telford, W.G. A reappraisal of the role of zinc in life and death decisions of cells. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. (New York, NY) 1997, 215, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong-Tran, A.Q.; Carter, J.; Ruffin, R.E.; Zalewski, P.D. The role of Zinc in caspase activation and apoptotic cell death. Biometals 2001, 14, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, B.; Pal, S.; Tran, M.P.; Parsons, A.A.; Barone, F.C.; Erhardt, J.A.; Aizenman, E. p38 activation is required upstream of potassium current enhancement and caspase cleavage in thiol oxidant-induced neuronal apoptosis. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 3303–3311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wiseman, D.A.; Wells, S.M.; Wilham, J.; Hubbard, M.; Welker, J.E.; Black, S.M. Endothelial response to stress from exogenous Zn2+ resembles that of NO-mediated nitrosative stress, and is protected by MT-1 overexpression. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 291, C555–C568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.E.; Kovacic, J.P. The ubiquitous role of Zinc in health and disease. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care (San Antonio, Tex. 2001) 2009, 19, 215–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hambidge, K.M.; Olivarasbach, J.; Jacobs, M.; Purcell, S.; Statland, C.; Poirier, J. Randomized study of Zinc supplementation during pregnancy. Fed. Proc. 1986, 45, 974. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.A.; Thom, J.V.; Orth, G.L.; Cova, P.; Juarez, J. Food poisoning involving zinc contamination. Arch. Environ. Health 1964, 8, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uski, O.; Torvela, T.; Sippula, O.; Karhunen, T.; Koponen, H.; Peraniemi, S.; Jalava, P.; Happo, M.; Jokiniemi, J.; Hirvonen, M.R.; et al. In vitro toxicological effects of Zinc containing nanoparticles with different physico-chemical properties. Toxicol. In Vitro 2017, 42, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanjuk, A.; Lyndin, M.; Moskalenko, R.; Gortinskaya, O.; Lyndina, Y. The role of heavy metal salts in pathological biomineralization of breast cancer tissue. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2016, 25, 907–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, B.X.; Han, B.; Shaw, D.G.; Nimni, M. Zinc as a possible preventive and therapeutic agent in pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 25, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, C. Zinc: Physiology, deficiency, and parenteral nutrition. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2015, 30, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera, A.J. Zinc, aging, and immunosenescence: An overview. Pathobiol. Aging Age Relat. Dis. 2015, 5, 25592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Chiche, J.; Pouyssegur, J.; Sato, H.; Fukuzawa, H.; Nagao, M.; Kambe, T. Dissecting the process of activation of cancer-promoting Zinc-requiring ectoenzymes by Zinc metalation mediated by ZNT transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2159–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aamodt, R.L.; Rumble, W.F.; Johnston, G.S.; Foster, D.; Henkin, R.I. Zinc metabolism in humans after oral and intravenous administration of Zn-69m. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1979, 32, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Little, P.J.; Bhattacharya, R.; Moreyra, A.E.; Korichneva, I.L. Zinc and cardiovascular disease. Nutrition 2010, 26, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimelli, A.; Menichetti, F.; Soldati, E.; Liga, R.; Vannozzi, A.; Marzullo, P.; Bongiorni, M.G. Relationships between cardiac innervation/perfusion imbalance and ventricular arrhythmias: Impact on invasive electrophysiological parameters and ablation procedures. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 2383–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Q.; Liu, Q.; Sun, J.; Zheng, Y.; Cai, L. Zinc prevents the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy in db/db mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozym, R.A.; Chimienti, F.; Giblin, L.J.; Gross, G.W.; Korichneva, I.; Li, Y.; Libert, S.; Maret, W.; Parviz, M.; Frederickson, C.J.; et al. Free Zinc ions outside a narrow concentration range are toxic to a variety of cells in vitro. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood, NJ) 2010, 235, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efeovbokhan, N.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Ahokas, R.A.; Sun, Y.; Guntaka, R.V.; Gerling, I.C.; Weber, K.T. Zinc and the prooxidant heart failure phenotype. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 64, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashemian, M.; Poustchi, H.; Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, F.; Hekmatdoost, A. Systematic review of Zinc biochemical indicators and risk of coronary heart disease. ARYA Atheroscler. 2015, 11, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.R.; Noh, S.J.; Pronto, J.R.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, H.K.; Song, I.S.; Xu, Z.; Kwon, H.Y.; Kang, S.C.; Sohn, E.H.; et al. The critical roles of Zinc: Beyond impact on myocardial signaling. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 19, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, A.; Foster, M.; Samman, S. Zinc Status and risk of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus-a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Nutrients 2016, 8, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tatsumi, T.; Fliss, H. Hypochlorous acid and chloramines increase endothelial permeability: Possible involvement of cellular zinc. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267 Pt 2, H1597–H1607. [Google Scholar]

- Turan, B. Zinc-induced changes in ionic currents of cardiomyocytes. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2003, 94, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zima, A.V.; Blatter, L.A. Redox regulation of cardiac calcium channels and transporters. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 71, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dineley, K.E.; Richards, L.L.; Votyakova, T.V.; Reynolds, I.J. Zinc causes loss of membrane potential and elevates reactive oxygen species in rat brain mitochondria. Mitochondrion 2005, 5, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayaz, M.; Turan, B. Selenium prevents diabetes-induced alterations in [Zn2+]i and metallothionein level of rat heart via restoration of cell redox cycle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006, 290, H1071–H1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maret, W. Molecular aspects of human cellular zinc homeostasis: Redox control of zinc potentials and zinc signals. Biometals 2009, 22, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuster, G.M.; Lancel, S.; Zhang, J.; Communal, C.; Trucillo, M.P.; Lim, C.C.; Pfister, O.; Weinberg, E.O.; Cohen, R.A.; Liao, R.; et al. Redox-mediated reciprocal regulation of SERCA and Na+-Ca2+ exchanger contributes to sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ depletion in cardiac myocytes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 1182–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranasinghe, P.; Pigera, S.; Galappatthy, P.; Katulanda, P.; Constantine, G.R. Zinc and diabetes mellitus: Understanding molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Daru 2015, 23, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuncay, E.; Okatan, E.N.; Toy, A.; Turan, B. Enhancement of cellular antioxidant-defence preserves diastolic dysfunction via regulation of both diastolic Zn2+ and Ca2+ and prevention of RyR2-leak in hyperglycemic cardiomyocytes. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, 290381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalov, G.; Ahokas, R.A.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, T.; Shahbaz, A.U.; Johnson, P.L.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Sun, Y.; Gerling, I.C.; Weber, K.T. Uncoupling the coupled calcium and zinc dyshomeostasis in cardiac myocytes and mitochondria seen in aldosteronism. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2010, 55, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reilly-O’Donnell, B.; Robertson, G.B.; Karumbi, A.; McIntyre, C.; Bal, W.; Nishi, M.; Takeshima, H.; Stewart, A.J.; Pitt, S.J. Dysregulated Zn2+ homeostasis impairs cardiac type-2 ryanodine receptor and mitsugumin 23 functions, leading to sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ leakage. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13361–13373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugger, D.; Windisch, W.M. Short-term subclinical Zinc deficiency in weaned piglets affects cardiac redox metabolism and Zinc concentration. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Permyakov, E.A.; Kretsinger, R.H. Cell signaling, beyond cytosolic calcium in eukaryotes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T.; Murakami, M.; Fukada, T.; Nishida, K.; Yamasaki, S.; Suzuki, T. Roles of Zinc and Zinc signaling in immunity: Zinc as an intracellular signaling molecule. Adv. Immunol. 2008, 97, 149–176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cicek, F.A.; Tokcaer-Keskin, Z.; Ozcinar, E.; Bozkus, Y.; Akcali, K.C.; Turan, B. Di-peptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin protects vascular function in metabolic syndrome: Possible role of epigenetic regulation. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 4853–4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

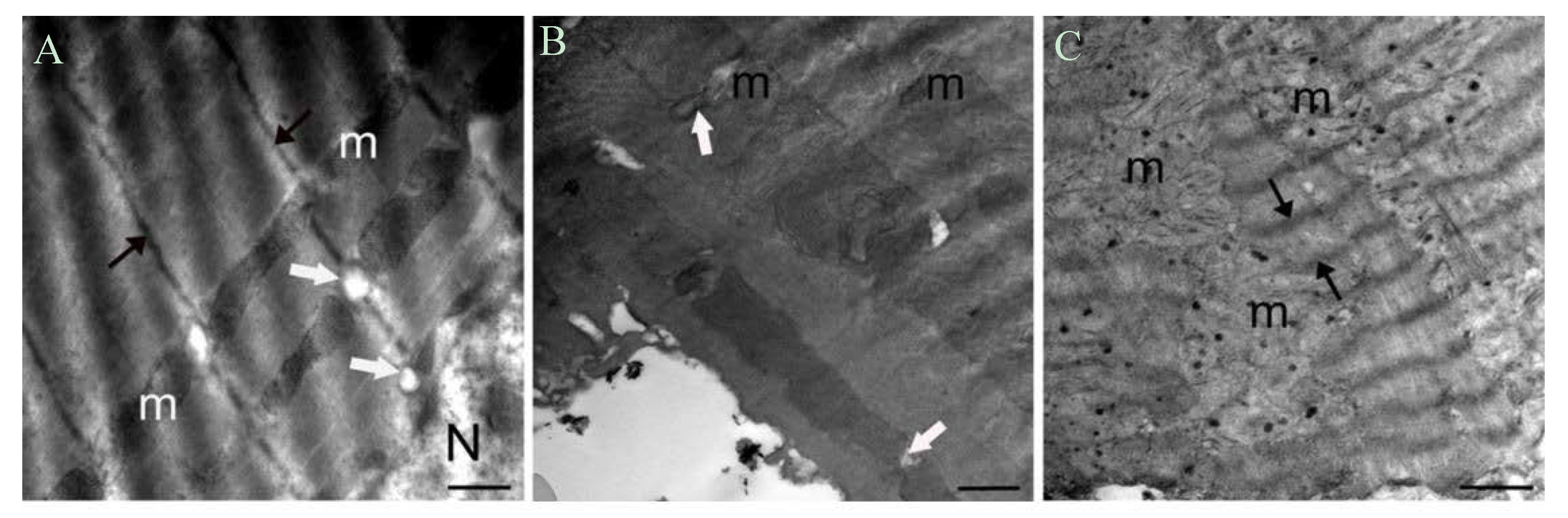

- Billur, D.; Tuncay, E.; Okatan, E.N.; Olgar, Y.; Durak, A.T.; Degirmenci, S.; Can, B.; Turan, B. Interplay between cytosolic free Zn2+ and mitochondrion morphological changes in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes. Biol. Trace Element Res. 2016, 174, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Gu, J.; Chen, J.; Payne, K.M.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Zinc deficiency exacerbates while Zinc supplement attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in high-fat diet-induced obese mice through modulating p38 MAPK-dependent signaling. Toxicol. Lett. 2016, 258, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Bromberg, P.A.; Samet, J.M. Zinc ions as effectors of environmental oxidative lung injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plum, L.M.; Rink, L.; Haase, H. The essential toxin: Impact of Zinc on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010, 7, 1342–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaras, N.; Ugur, M.; Ozdemir, S.; Gurdal, H.; Purali, N.; Lacampagne, A.; Vassort, G.; Turan, B. Effects of diabetes on ryanodine receptor Ca release channel (RyR2) and Ca2+ homeostasis in rat heart. Diabetes 2005, 54, 3082–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermak, G.; Davies, K.J. Calcium and oxidative stress: From cell signaling to cell death. Mol. Immunol. 2002, 38, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, T.; Ghosh, S.K.; Michael, J.R.; Batabyal, S.K.; Chakraborti, S. Targets of oxidative stress in cardiovascular system. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1998, 187, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakami, M.; Okabe, E. Superoxide anion radical-triggered Ca2+ release from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum through ryanodine receptor Ca2+ channel. Mol. Pharmacol. 1998, 53, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boraso, A.; Williams, A.J. Modification of the gating of the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel by H2O2 and dithiothreitol. Am. J. Physiol. 1994, 267 Pt 2, H1010–H1016. [Google Scholar]

- Woodier, J.; Rainbow, R.D.; Stewart, A.J.; Pitt, S.J. Intracellular Zinc modulates cardiac ryanodine receptor-mediated Calcium release. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 17599–17610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.J.; Pitt, S.J. Zinc controls RyR2 activity during excitation-contraction coupling. Channels 2015, 9, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kamalov, G.; Ahokas, R.A.; Zhao, W.; Shahbaz, A.U.; Bhattacharya, S.K.; Sun, Y.; Gerling, I.C.; Weber, K.T. Temporal responses to intrinsically coupled Calcium and Zinc dyshomeostasis in cardiac myocytes and mitochondria during aldosteronism. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 298, H385–H394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Zhu, P.H. Biphasic modulation of ryanodine receptors by sulfhydryl oxidation in rat ventricular myocytes. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 2882–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Clausell, J.; Danscher, G. Intravesicular localization of Zinc in rat telencephalic boutons. A histochemical study. Brain Res. 1985, 337, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomianka, L. Neurons of origin of Zinc-containing pathways and the distribution of Zinc-containing boutons in the hippocampal region of the rat. Neuroscience 1992, 48, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekler, I.; Sensi, S.L.; Hershfinkel, M.; Silverman, W.F. Mechanism and regulation of cellular Zinc transport. Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerchner, G.A.; Canzoniero, L.M.; Yu, S.P.; Ling, C.; Choi, D.W. Zn2+ current is mediated by voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and enhanced by extracellular acidity in mouse cortical neurones. J. Physiol. 2000, 528 Pt 1, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Collazo, J.; Diaz-Garcia, C.M.; Lopez-Medina, A.I.; Vassort, G.; Alvarez, J.L. Zinc modulation of basal and β-adrenergically stimulated l-type Ca2+ current in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes: Consequences in cardiac diseases. Pflugers Arch. 2012, 464, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traynelis, S.F.; Burgess, M.F.; Zheng, F.; Lyuboslavsky, P.; Powers, J.L. Control of voltage-independent Zinc inhibition of NMDA receptors by the NR1 subunit. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 6163–6175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Kehl, S.J.; Fedida, D. Modulation of Kv1.5 potassium channel gating by extracellular Zinc. Biophys. J. 2001, 81, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilly, W.F.; Armstrong, C.M. Slowing of sodium channel opening kinetics in squid axon by extracellular Zinc. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982, 79, 935–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilly, W.F.; Armstrong, C.M. Divalent cations and the activation kinetics of potassium channels in squid giant axons. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982, 79, 965–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aras, M.A.; Saadi, R.A.; Aizenman, E. Zn2+ regulates Kv2.1 voltage-dependent gating and localization following ischemia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009, 30, 2250–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, H.; Maret, W. Intracellular Zinc fluctuations modulate protein tyrosine phosphatase activity in insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling. Exp. Cell Res. 2003, 291, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bulow, V.; Rink, L.; Haase, H. Zinc-mediated inhibition of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity and expression suppresses TNF-α and IL-1 β production in monocytes by elevation of guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 4697–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heyden, M.A.; Wijnhoven, T.J.; Opthof, T. Molecular aspects of adrenergic modulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 65, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.; Hogstrand, C.; Maret, W. Picomolar concentrations of free zinc(II) ions regulate receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase beta activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 9322–9326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.M.; Hiscox, S.; Nicholson, R.I.; Hogstrand, C.; Kille, P. Protein kinase CK2 triggers cytosolic Zinc signaling pathways by phosphorylation of Zinc channel ZIP7. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, C.; Sunahara, R.K.; Hudson, T.Y.; Heyduk, T.; Howlett, A.C. Zinc inhibition of cAMP signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 11859–11865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Du, Z.; Patel, T.B. Copper and Zinc inhibit Galphas function: A nucleotide-free state of Galphas induced by Cu2+ and Zn2+. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2579–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltas, L.G.; Karczewski, P.; Bartel, S.; Krause, E.G. The endogenous cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase is activated in response to β-adrenergic stimulation and becomes Ca2+-independent in intact beating hearts. FEBS Lett. 1997, 409, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, T.; Vick, J.S.; Vecchio, M.J.; Begin, K.J.; Bell, S.P.; Delay, R.J.; Palmer, B.M. Identifying cellular mechanisms of Zinc-induced relaxation in isolated cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013, 305, H706–H715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Boillat, A.; Huang, D.; Liang, C.; Peers, C.; Gamper, N. Intracellular zinc activates KCNQ channels by reducing their dependence on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6410–E6419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sensi, S.L.; Paoletti, P.; Bush, A.I.; Sekler, I. Zinc in the physiology and pathology of the CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 10, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederickson, C.J.; Koh, J.Y.; Bush, A.I. The neurobiology of Zinc in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maret, W. Zinc coordination environments in proteins as redox sensors and signal transducers. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 1419–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dineley, K.E.; Devinney, M.J., 2nd; Zeak, J.A.; Rintoul, G.L.; Reynolds, I.J. Glutamate mobilizes [Zn2+] through Ca2+ -dependent reactive oxygen species accumulation. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 2184–2193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ellis, C.D.; Wang, F.; MacDiarmid, C.W.; Clark, S.; Lyons, T.; Eide, D.J. Zinc and the MSC2 Zinc transporter protein are required for endoplasmic reticulum function. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 166, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sensi, S.L.; Ton-That, D.; Weiss, J.H. Mitochondrial sequestration and Ca2+-dependent release of cytosolic Zn2+ loads in cortical neurons. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002, 10, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chance, B.; Sies, H.; Boveris, A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol. Rev. 1979, 59, 527–605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dedkova, E.N.; Blatter, L.A. Characteristics and function of cardiac mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. J. Physiol. 2009, 587 Pt 4, 851–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouron, A.; Kiselyov, K.; Oberwinkler, J. Permeation, regulation and control of expression of TRP channels by trace metal ions. Pflugers Arch. 2015, 467, 1143–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Iribe, G.; Nishida, M.; Naruse, K. Role of TRPC3 and TRPC6 channels in the myocardial response to stretch: Linking physiology and pathophysiology. Progress Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Takeuchi, A.; Hai-Kurahara, L.; Ichikawa, J.; Hiraishi, K.; Numata, T.; Ohara, H.; Iribe, G.; Nakaya, M.; et al. Uncovering the arrhythmogenic potential of TRPM4 activation in atrial-derived HL-1 cells using novel recording and numerical approaches. Cardiovasc. Res. 2017, 113, 1243–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, K.; Tominaga, M. Extracellular Zinc ion regulates transient receptor potential melastatin 5 (TRPM5) channel activation through its interaction with a pore loop domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 25950–25955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, S.; Drews, A.; Rizun, O.; Wagner, T.F.; Lis, A.; Mannebach, S.; Plant, S.; Portz, M.; Meissner, M.; Philipp, S.E.; et al. Transient receptor potential melastatin 1 (TRPM1) is an ion-conducting plasma membrane channel inhibited by Zinc ions. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 12221–12233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiria, S.A.; Krapivinsky, G.; Sah, R.; Santa-Cruz, A.G.; Chaudhuri, D.; Zhang, J.; Adstamongkonkul, P.; DeCaen, P.G.; Clapham, D.E. TRPM7 senses oxidative stress to release Zn2+ from unique intracellular vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6079–E6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Li, S. Role of transient receptor potential channels in heart transplantation: A potential novel therapeutic target for cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 2340–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, Y.; Wang, H.; Xi, J.; Mueller, R.A.; Norfleet, E.A.; Xu, Z. NO mobilizes intracellular Zn2+ via cGMP/PKG signaling pathway and prevents mitochondrial oxidant damage in cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007, 75, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T.; Fukada, T.; Toyokuni, S. Editorial: The cutting edge of zinc biology. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 611, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Kambe, T. The functions of metallothionein and ZIP and ZnT transporters: An overview and perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Myers, S.A. Zinc transporters and Zinc signaling: New insights into their role in type 2 diabetes. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 167503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Tepaamorndech, S. The SLC30 family of zinc transporters-a review of current understanding of their biological and pathophysiological roles. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.; Eide, D.J. The SLC39 family of Zinc transporters. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013, 34, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T. Methods to evaluate Zinc transport into and out of the secretory and endosomal-lysosomal compartments in DT40 cells. Methods Enzymol. 2014, 534, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Fujimoto, S. Current understanding of ZIP and ZnT zinc transporters in human health and diseases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2014, 71, 3281–3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima, T.; Jesmin, S.; Matsui, T.; Soya, M.; Soya, H. Differential effects of type 2 diabetes on brain glycometabolism in rats: Focus on glycogen and monocarboxylate transporter 2. J. Physiol. Sci. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, H.M.; Yang, C.Y.; Wang, M.L.; Ma, H.J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y. K(ATP) channels and MPTP are involved in the cardioprotection bestowed by chronic intermittent hypobaric hypoxia in the developing rat. J. Physiol. Sci. 2015, 65, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.C.; Shames, D.M.; Woodhouse, L.R. Zinc homeostasis in humans. J. Nutr. 2000, 130 (Suppl. S5), 1360s–1366s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palmiter, R.D.; Findley, S.D. Cloning and functional characterization of a mammalian Zinc transporter that confers resistance to Zinc. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, H.J.; Cole, T.B.; Born, D.E.; Schwartzkroin, P.A.; Palmiter, R.D. Ultrastructural localization of Zinc transporter-3 (ZnT-3) to synaptic vesicle membranes within mossy fiber boutons in the hippocampus of mouse and monkey. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 12676–12681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T.; Weaver, B.P.; Andrews, G.K. The genetics of essential metal homeostasis during development. Genesis 2008, 46, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bin, B.H.; Fukada, T.; Hosaka, T.; Yamasaki, S.; Ohashi, W.; Hojyo, S.; Miyai, T.; Nishida, K.; Yokoyama, S.; Hirano, T. Biochemical characterization of human ZIP13 protein: A homo-dimerized zinc transporter involved in the spondylocheiro dysplastic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 40255–40265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.M.; Morgan, H.E.; Smart, K.; Zahari, N.M.; Pumford, S.; Ellis, I.O.; Robertson, J.F.; Nicholson, R.I. The emerging role of the LIV-1 subfamily of Zinc transporters in breast cancer. Mol. Med. 2007, 13, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kambe, T.; Geiser, J.; Lahner, B.; Salt, D.E.; Andrews, G.K. Slc39a1 to 3 (subfamily II) Zip genes in mice have unique cell-specific functions during adaptation to Zinc deficiency. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2008, 294, R1474–R1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Yu, Y.Y.; Kirschke, C.P.; Gertz, E.R.; Lloyd, K.K. Znt7 (Slc30a7)-deficient mice display reduced body Zinc status and body fat accumulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37053–37063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Kirschke, C.P.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.Y. The ZIP7 gene (Slc39a7) encodes a Zinc transporter involved in Zinc homeostasis of the Golgi apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 15456–15463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sladek, R.; Rocheleau, G.; Rung, J.; Dina, C.; Shen, L.; Serre, D.; Boutin, P.; Vincent, D.; Belisle, A.; Hadjadj, S.; et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature 2007, 445, 881–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzlau, J.M.; Juhl, K.; Yu, L.; Moua, O.; Sarkar, S.A.; Gottlieb, P.; Rewers, M.; Eisenbarth, G.S.; Jensen, J.; Davidson, H.W.; et al. The cation efflux transporter ZnT8 (Slc30A8) is a major autoantigen in human type 1 diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 17040–17045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaire, K.; Ravier, M.A.; Schraenen, A.; Creemers, J.W.; Van de Plas, R.; Granvik, M.; Van Lommel, L.; Waelkens, E.; Chimienti, F.; Rutter, G.A.; et al. Insulin crystallization depends on Zinc transporter ZnT8 expression, but is not required for normal glucose homeostasis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 14872–14877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolson, T.J.; Bellomo, E.A.; Wijesekara, N.; Loder, M.K.; Baldwin, J.M.; Gyulkhandanyan, A.V.; Koshkin, V.; Tarasov, A.I.; Carzaniga, R.; Kronenberger, K.; et al. Insulin storage and glucose homeostasis in mice null for the granule zinc transporter ZnT8 and studies of the type 2 diabetes-associated variants. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2070–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesekara, N.; Dai, F.F.; Hardy, A.B.; Giglou, P.R.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Koshkin, V.; Chimienti, F.; Gaisano, H.Y.; Rutter, G.A.; Wheeler, M.B. β cell-specific ZnT8 deletion in mice causes marked defects in insulin processing, crystallisation and secretion. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 1656–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaki, M.; Fujitani, Y.; Hara, A.; Uchida, T.; Tamura, Y.; Takeno, K.; Kawaguchi, M.; Watanabe, T.; Ogihara, T.; Fukunaka, A.; et al. The diabetes-susceptible gene Slc30A8/ZnT8 regulates hepatic insulin clearance. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 4513–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabosseau, P.; Rutter, G.A. Zinc and diabetes. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 611, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, G.A.; Chabosseau, P.; Bellomo, E.A.; Maret, W.; Mitchell, R.K.; Hodson, D.J.; Solomou, A.; Hu, M. Intracellular Zinc in insulin secretion and action: A determinant of diabetes risk? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogstrand, C.; Kille, P.; Nicholson, R.I.; Taylor, K.M. Zinc transporters and cancer: A potential role for ZIP7 as a hub for tyrosine kinase activation. Trends Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.M.; Vichova, P.; Jordan, N.; Hiscox, S.; Hendley, R.; Nicholson, R.I. ZIP7-mediated intracellular Zinc transport contributes to aberrant growth factor signaling in antihormone-resistant breast cancer Cells. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 4912–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Batchuluun, B.; Ho, L.; Zhu, D.; Prentice, K.J.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Zhang, M.; Pourasgari, F.; Hardy, A.B.; Taylor, K.M.; et al. Characterization of Zinc influx transporters (ZIPs) in pancreatic β cells: Roles in regulating cytosolic Zinc homeostasis and insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18757–18769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubman, A.; Lidgerwood, G.E.; Duncan, C.; Bica, L.; Tan, J.L.; Parker, S.J.; Caragounis, A.; Meyerowitz, J.; Volitakis, I.; Moujalled, D.; et al. Deregulation of subcellular biometal homeostasis through loss of the metal transporter, ZIP7, in a childhood neurodegenerative disorder. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2014, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, C.; Sasamura, T.; Khanna, M.R.; Whitley, M.; Fortini, M.E. Protein trafficking abnormalities in Drosophila tissues with impaired activity of the ZIP7 Zinc transporter Catsup. Development 2013, 140, 3018–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohashi, W.; Kimura, S.; Iwanaga, T.; Furusawa, Y.; Irie, T.; Izumi, H.; Watanabe, T.; Hijikata, A.; Hara, T.; Ohara, O.; et al. Zinc Transporter Slc39A7/ZIP7 promotes intestinal epithelial self-renewal by resolving ER stress. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschke, C.P.; Huang, L. ZnT7, a novel mammalian Zinc transporter, accumulates Zinc in the Golgi apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4096–4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; Yao, W.; Yu, X.; Cen, P.; Hodges, S.E.; Fisher, W.E.; Brunicardi, F.C.; Chen, C.; et al. Gene profile identifies Zinc transporters differentially expressed in normal human organs and human pancreatic cancer. Curr. Mol. Med. 2013, 13, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haase, H.; Maret, W. Fluctuations of cellular, available zinc modulate insulin signaling via inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphatases. J. Trace Elements Med. Biol. Organ Soc. Miner. Trace Elements (GMS) 2005, 19, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, S.; Sakata-Sogawa, K.; Hasegawa, A.; Suzuki, T.; Kabu, K.; Sato, E.; Kurosaki, T.; Yamashita, S.; Tokunaga, M.; Nishida, K.; et al. Zinc is a novel intracellular second messenger. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 177, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, S.A.; Nield, A.; Myers, M. Zinc transporters, mechanisms of action and therapeutic utility: Implications for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 173712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, J.; Karges, W.; Rink, L. Zinc and diabetes—Clinical links and molecular mechanisms. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2009, 20, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameters | Excess Zn2+ | Parameters | Excess Zn2+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical activity | Mechanical activity | ||

| Resting membrane potential | ↔ | Muscle Contraction | ↓ |

| Action potential duration (APD) Time to peak AP amplitude (TP) | ↔ ↑ | Contraction rate Relaxation rate | ↓ ↓ |

| Ca2+ transients | ↓ | Time to peak contraction | ↔ |

| L-type Ca2+ currents | ↓ | Time at 50% of relaxation | ↔ |

| Mitochondrial membrane potential | ↑ |

| Parameters | Excess Zn2+ | Parameters | Excess Zn2+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical parameters | ||||

| pRyR2/RyR2 | ↑ | Promyelocytic leukemia(PML) | ↑ | |

| pPKA/PKA | ↑ | Bcl-2/BAX | ↓ | |

| FK506-binding protein(FKBP12.6) | ↔ | pAkt/Akt | ↑ | |

| pCaMKII/CaMKII | ↑ | pNFκB/NFκB | ↑ | |

| Calregulin | ↑ | pGSK/GSK | ↑ | |

| Glucose regulated protein (GRP78) | ↑ | |||

| Ultrastructure parameters | ||||

| Morphological changes in mitochondria | ↑ | Electron density of Z-lines | ↓ | |

| Number of lysosomes | ↑ | |||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Turan, B.; Tuncay, E. Impact of Labile Zinc on Heart Function: From Physiology to Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18112395

Turan B, Tuncay E. Impact of Labile Zinc on Heart Function: From Physiology to Pathophysiology. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017; 18(11):2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18112395

Chicago/Turabian StyleTuran, Belma, and Erkan Tuncay. 2017. "Impact of Labile Zinc on Heart Function: From Physiology to Pathophysiology" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 18, no. 11: 2395. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18112395