The Risk of Congenital Heart Anomalies Following Prenatal Exposure to Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors—Is Pharmacogenetics the Key?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Risk of Congenital Heart Anomalies (CHA) Associated with Maternal Use of Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SRIs) during the First Trimester of Pregnancy

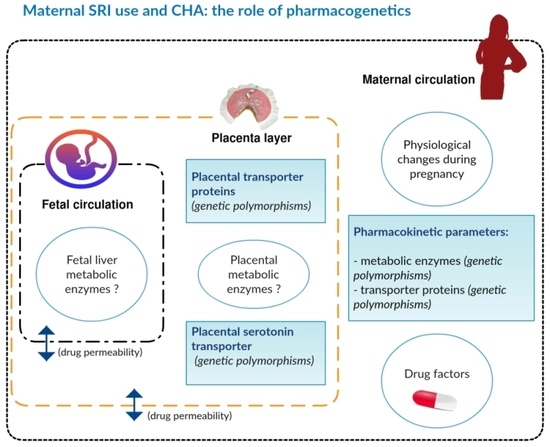

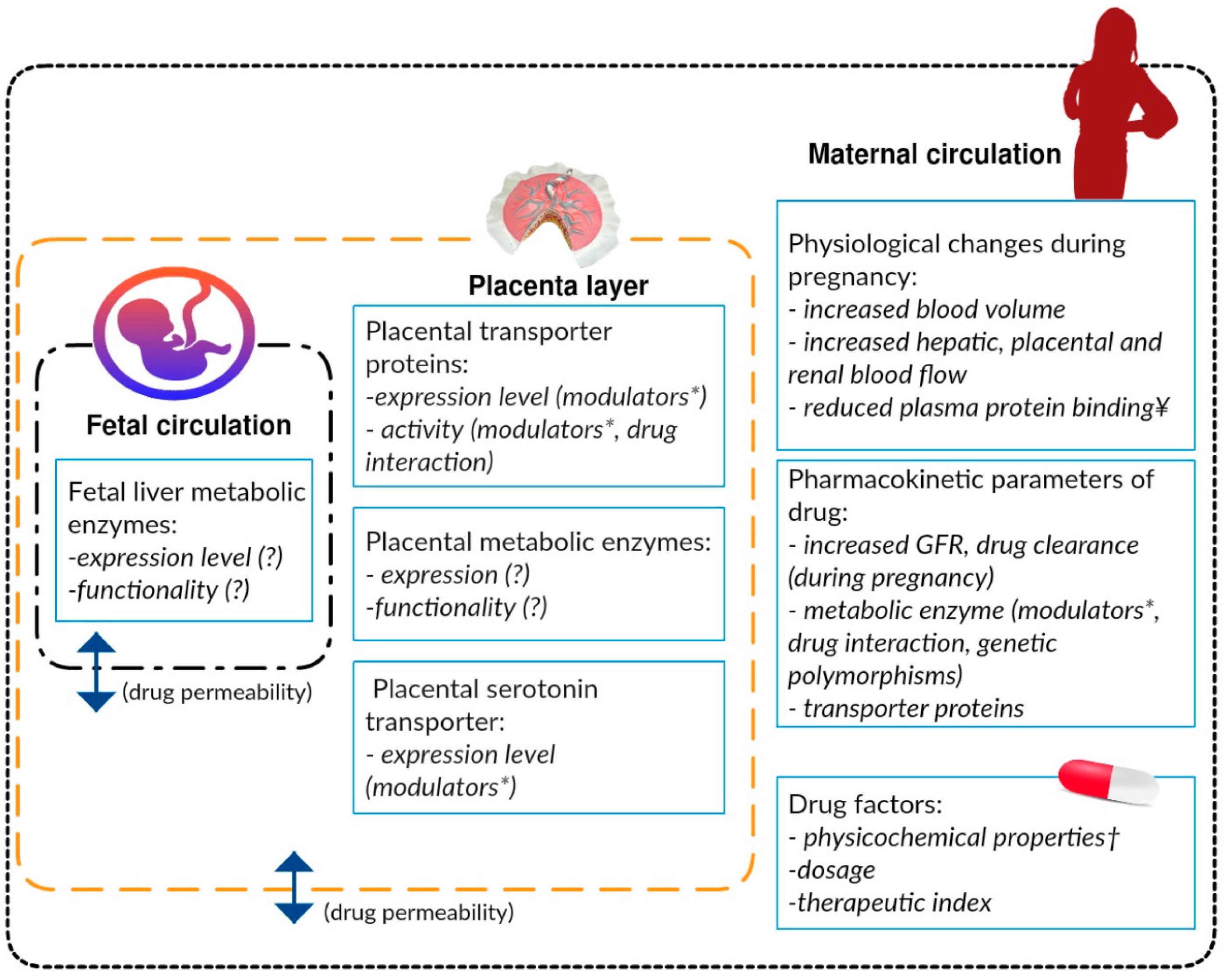

3. Pharmacogenetic Predictors of SRI Pharmacokinetics

3.1. Maternal Metabolic Enzymes

3.2. Foetal Metabolic Enzymes

3.3. Placental Transporter Proteins

4. Pharmacogenetic Predictors of CHA Associated with Exposure to SRIs

4.1. Serotonin Transporter in Foetal Cardiac Cells and in the Placenta

4.2. Foetal Serotonin Receptors

4.3. Other Genes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alwan, S.; Reefhuis, J.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Friedman, J.M. Patterns of antidepressant medication use among pregnant women in a United States population. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 51, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, M.K.; Kölling, P.; van den Berg, P.B.; de Walle, H.E.; de Jong van den Berg, L.T. Increase in use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy during the last decade, a population-based cohort study from the Netherlands. Br. J. Clin Pharmacol. 2008, 65, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlton, R.; Jordan, S.; Pierini, A.; Garne, E.; Neville, A.J.; Hansen, A.V.; Gini, R.; Thayer, D.; Tinqay, K.; Puccini, A.; et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor prescribing before, during and after pregnancy: A population-based study in six European regions. BJOG 2014, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andrade, S.E.; Raebel, M.A.; Brown, J.; Lane, K.; Livingston, J.; Boudreau, D.; Rolnick, S.J.; Roblin, D.; Smith, D.H.; Willy, M.E.; et al. Use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy: A multisite study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 198, 194–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobo, W.V.; Epstein, R.A., Jr.; Hayes, R.M.; Shelton, R.C.; Hartert, T.V.; Mitchel, E.; Horner, J.; Wu, P. The effect of regulatory advisories on maternal antidepressant prescribing, 1995–2007: An interrupted time series study of 228,876 pregnancies. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2014, 17, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bérard, A.; Zhao, J.-P.; Sheehy, O. Sertraline use during pregnancy and the risk of major malformations. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 212, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wemakor, A.; Casson, K.; Garne, E.; Bakker, M.; Addor, M.-C.; Arriola, L.; Gatt, M.; Khoshnood, B.; Klungsoyr, K.; Nelen, V.; et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant use in first trimester pregnancy and risk of specific congenital anomalies: A European register-based study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 30, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban, L.; Gibson, J.; West, J.; Fiaschi, L.; Sokal, R.; Smeeth, L.; Dolye, P.; Hubbard, R.B.; Tala, L.J. Maternal depression, antidepressant prescriptions, and congenital anomaly risk in offspring: A population-based cohort study. BJOG 2014, 121, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, T.; Hansen, A.; Garne, E.; Andersen, A.-M. Increased risk of severe congenital heart defects in offspring exposed to selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in early pregnancy—An epidemiological study using validated EUROCAT data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polen, K.N.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; Reefhuis, J.; Study, N.B.D.P. Association between reported venlafaxine use in early pregnancy and birth defects, national birth defects prevention study, 1997–2007. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2013, 97, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malm, H.; Artama, M.; Gissler, M.; Ritvanen, A. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk for major congenital anomalies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 118, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, M.; Kallen, B. Delivery outcome after maternal use of antidepressant drugs in pregnancy: An update using Swedish data. Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 1723–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, M.K.; Kerstjens-Frederikse, W.S.; Buys, C.H.; de Walle, H.E.; de Jong-van den Berg, L.T. First-trimester use of paroxetine and congenital heart defects: A population-based case-control study. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2010, 88, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlob, P.; Birk, E.; Sirota, L.; Linder, N.; Berant, M.; Stahl, B.; Kinger, G. Are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors cardiac teratogens? Echocardiographic screening of newborns with persistent heart murmur. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2009, 85, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, L.H.; Henriksen, T.B.; Vestergaard, M.; Olsen, J.; Bech, B.H. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and congenital malformations: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2009, 339, b3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diav-Citrin, O.; Shechtman, S.; Weinbaum, D.; Wajnberg, R.; Avgil, M.; Gianantonio, E.D.; Clementi, M.; Weber-Schoendorfer, C.; Schaefer, C.; Ornoy, A. Paroxetine and fluoxetine in pregnancy: A prospective, multicentre, controlled, observational study. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 66, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberlander, T.F.; Warburton, W.; Misri, S.; Riggs, W.; Aghajanian, J.; Hertzman, C. Major congenital malformations following prenatal exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors and benzodiazepines using population-based health data. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 2008, 83, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.A.; Ephross, S.A.; Cosmatos, I.S.; Walker, A.M. Paroxetine in the first trimester and the prevalence of congenital anomalies. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007, 16, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louik, C.; Lin, A.E.; Werler, M.M.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Mitchell, A.A. First-trimester use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2675–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Källén, B.A.J.; Olausson, P.O. Maternal use of selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors in early pregnancy and infant congenital malformations. Birth Defects Res. Part A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2007, 79, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berard, A.; Ramos, E.; Rey, E.; Blais, L.; St-Andre, M.; Oraichi, D. First trimester exposure to paroxetine and risk of cardiac malformations in infants: The importance of dosage. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 80, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wogelius, P.; Nørgaard, M.; Gislum, M.; Pedersen, L.; Munk, E.; Mortensen, P.B.; Lipworth, L.; Sorensen, H.T. Maternal use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of congenital malformations. Epidemiology 2006, 17, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furu, K.; Kieler, H.; Haglund, B.; Engeland, A.; Selmer, R.; Stephansson, O.; Valdimarsdottir, U.A.; Zoega, H.; Artama, M.; Gissler, M.; et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine in early pregnancy and risk of birth defects: Population based cohort study and sibling design. BMJ 2015, 350, h1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huybrechts, K.F.; Palmsten, K.; Avorn, J.; Cohen, L.S.; Holmes, L.B.; Franklin, J.M.; Mogun, H.; Levin, R.; Kowal, M.; Setoguchi, S.; et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilakis-Scaramozza, C.; Aschengrau, A.; Cabral, H.; Jick, S.S. Antidepressant use during early pregnancy and the risk of congenital anomalies. Pharmacotherapy 2013, 33, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margulis A, V.; Abou-Ali, A.; Strazzeri, M.M.; Ding, Y.; Kuyateh, F.; Frimpong, E.Y.; Levenson, M.S.; Hammad, T.A. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and cardiac malformations: A propensity-score matched cohort in CPRD. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2013, 22, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klieger-Grossmann, C.; Weitzner, B.; Panchaud, A.; Pistelli, A.; Einarson, T.; Koren, G.; Einarson, A. Pregnancy Outcomes Following Use of Escitalopram: A Prospective Comparative Cohort Study. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 52, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarson, A.; Choi, J.; Einarson, T.R.; Koren, G. Incidence of major malformations in infants following antidepressant exposure in pregnancy: Results of a large prospective cohort study. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichman, C.L.; Moore, K.M.; Lang, T.R.; St Sauver, J.L.; Heise, R.H.J.; Watson, W.J. Congenital heart disease associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during pregnancy. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2009, 84, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lennestål, R.; Källén, B. Delivery outcome in relation to maternal use of some recently introduced antidepressants. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, R.L.; Rubanowice, D.; McPhillips, H.; Rabael, M.A.; Andrade, S.E.; Smith, D.; Yod, M.U.; Platt, R.; HMO Research Network Center for Education, Research in Therapeutics. Risk of congenital malformations and perinatal events among infants exposed to antidepressant medications during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007, 16, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alwan, S.; Reefhuis, J.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Olney, R.S.; Friedman, J.M.; Study, N.B.D.P. Use of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth defects. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2684–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Solem, E.; Andersen, J.T.; Petersen, M.; Broedbaek, K.; Jensen, J.K.; Afzal, S.; Gislason, G.H.; Trop-Pedersen, C.; Poulsen, H.E. Exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and the risk of congenital malformations: A nationwide cohort study. BMJ Open 2012, 2, e001148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wurst, K.E.; Poole, C.; Ephross, S.A.; Olshan, A.F. First trimester paroxetine use and the prevalence of congenital, specifically cardiac, defects: A meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2010, 88, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigoriadis, S.; VonderPorten, E.H.; Mamisashvili, L.; Roerecke, M.; Rehm, J.; Dennis, C.-L.; Koren, G.; Steiner, M.; Mousmanis, P.; Sheung, A.; et al. Antidepressant exposure during pregnancy and congenital malformations: Is there an association? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the best evidence. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, e293–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myles, N.; Newall, H.; Ward, H.; Large, M. Systematic meta-analysis of individual selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications and congenital malformations. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2013, 47, 1002–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Gao, L.; Xu, B.; Xiong, Y. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and the Risk of Congenital Heart Defects: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grzeskowiak, L.E.; Gilbert, A.L.; Morrison, J.L. Exposed or not exposed? Exploring exposure classification in studies using administrative data to investigate outcomes following medication use during pregnancy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reefhuis, J.; Devine, O.; Friedman, J.M.; Louik, C.; Honein, M.A. Specific SSRIs and birth defects: Bayesian analysis to interpret new data in the context of previous reports. BMJ 2015, 350, h3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Linde, D.; Konings, E.E.M.; Slager, M.A.; Witsenburg, M.; Helbing, W.A.; Takkenberg, J.J.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isoherranen, N.; Thummel, K.E. Drug metabolism and transport during pregnancy: How does drug disposition change during pregnancy and what are the mechanisms that cause such changes? Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013, 41, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduljalil, K.; Furness, P.; Johnson, T.N.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A.; Soltani, H. Anatomical, physiological and metabolic changes with gestational age during normal pregnancy. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2012, 51, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, P.; Miller, R.K.; Schaefer, C. General commentary on drug therapy and drug risks in pregnancy. In Drugs During Pregnancy and Lactation, 3th ed.; Schaefer, C., Peters, P., Miller, R.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Munich, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, E.W.; Scialli, A.R.; Watson, R.E.; DeSesso, J.M. Mechanisms regulating toxicant disposition to the embryo during early pregnancy: An interspecies comparison. Birth Defects Res. Part C Embryo Today Rev. 2004, 72, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrick, V.; Stowe, Z.N.; Altshuler, L.L.; Hwang, S.; Lee, E.; Haynes, D. Placental passage of antidepressant medications. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 993–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampono, J.; Proud, S.; Hackett, L.P.; Kristensen, J.H.; Ilett, K.F. A pilot study of newer antidepressant concentrations in cord and maternal serum and possible effects in the neonate. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004, 7, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rampono, J.; Simmer, K.; Ilett, K.F.; Hackett, L.P.; Doherty, D.A.; Elliot, R.; Kok, C.H.; Coenen, A.; Forman, T. Placental transfer of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants and effects on the neonate. Pharmacopsychiatry 2009, 42, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altar, C.A.; Hornberger, J.; Shewade, A.; Cruz, V.; Garrison, J.; Mrazek, D. Clinical validity of cytochrome P450 metabolism and serotonin gene variants in psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myllynen, P.; Pasanen, M.; Vähäkangas, K. The fate and effects of xenobiotics in human placenta. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2007, 3, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myllynen, P.; Immonen, E.; Kummu, M.; Vähäkangas, K. Developmental expression of drug metabolizing enzymes and transporter proteins in human placenta and fetal tissues. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2009, 5, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storvik, M.; Huuskonen, P.; Pehkonen, P.; Pasanen, M. The unique characteristics of the placental transcriptome and the hormonal metabolism enzymes in placenta. Reprod. Toxicol. 2014, 47, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemeryck, A.; Belpaire, F.M. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and cytochrome P-450 mediated drug-drug interactions: An update. Curr. Drug Metab. 2002, 3, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiemke, C.; Härtter, S. Pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000, 85, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangkuhl, K.; Sting, J.C.; Turpeinen, M.; Altman, R.B.; Klein, T.E. PharmGKB summary: Venlafaxine pathway. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2012, 24, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knadler, M.P.; Lobo, E.; Chappell, J.; Bergstrom, R. Duloxetine: Clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2011, 50, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastoor, D.; Gobburu, J. Clinical pharmacology review of escitalopram for the treatment of depression. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2014, 10, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swen, J.J.; Wilting, I.; de Goede, A.L.; Grandia, L.; Mulder, H.; Touw, D.J.; van der Weide, J.; Wilffert, B.; Deneer, V.H.; Guchelaar, H.J. Pharmacogenetics: From bench to byte. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 83, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swen, J.J.; Nijenhuis, M.; de Boer, A.; Grandia, L.; Maitland-van der Zee, A.H.; Mulder, H.; Rongen, G.A.; van Schaik, R.H.; Schalekamp, T.; Touw, D.J.; et al. Pharmacogenetics: From bench to byte—An update of guidelines. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 89, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, J.K.; Bishop, J.R.; Sangkuhl, K.; Müller, D.J.; Ji, Y.; Leckband, S.G.; Leeder, J.S.; Graham, R.L.; Chiulli, D.L.; Llerena, A.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genotypes and Dosing of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 98, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Probst-Schendzielorz, K.; Viviani, R.; Stingl, J.C. Effect of Cytochrome P450 polymorphism on the action and metabolism of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2015, 11, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ververs, F.F.T.; Voorbij, H.A.M.; Zwarts, P.; Belitser, S.V.; Egberts, T.C.G.; Visser, G.H.A.; Schobben, A.F. Effect of cytochrome P450 2D6 genotype on maternal paroxetine plasma concentrations during pregnancy. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2009, 48, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LLerena, A.; Dorado, P.; Berecz, R.; González, A.P.; Peñas-LLedó, E.M. Effect of CYP2D6 and CYP2C9 genotypes on fluoxetine and norfluoxetine plasma concentrations during steady-state conditions. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 59, 869–873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scordo, M.G.; Spina, E.; Dahl, M.-L.; Gatti, G.; Perucca, E. Influence of CYP2C9, 2C19 and 2D6 genetic polymorphisms on the steady-state plasma concentrations of the enantiomers of fluoxetine and norfluoxetine. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005, 97, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasmäder, K.; Verwohlt, P.L.; Rietschel, M.; Dragicevic, A.; Müller, M.; Hiemke, C.; Freymann, N.; Zobel, A.; Maier, W.; Rao, M.L. Impact of polymorphisms of cytochrome-P450 isoenzymes 2C9, 2C19 and 2D6 on plasma concentrations and clinical effects of antidepressants in a naturalistic clinical setting. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 60, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burk, O.; Tegude, H.; Koch, I.; Hustert, E.; Wolbold, R.; Glaeser, H.; Klein, K.; Fromm, M.F.; Nuessler, A.K.; Neuhaus, P.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of polymorphic CYP3A7 expression in adult human liver and intestine. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 24280–24288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werk, A.N.; Cascorbi, I. Functional gene variants of CYP3A4. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 96, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanni, D.; Fanos, V.; Ambu, R.; Lai, F.; Gerosa, C.; Pampaloni, P.; van Eyken, P.; Senes, G.; Castsgnola, M.; Faa, G. Overlapping between CYP3A4 and CYP3A7 expression in the fetal human liver during development. J. Matern. Neonatal Med. 2015, 28, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, D.M.; Lehmann, A.S.; Skaar, T.; Philips, S.; McCormick, C.L.; Beagle, K.; Hebbring, S.J.; Dantzer, J.; Li, L.; Jung, J. The impact of drug metabolizing enzyme polymorphisms on outcomes after antenatal corticosteroid use. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, e17–e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakkola, J.; Pasanen, M.; Purkunen, R.; Saarikoski, S.; Pelkonen, O.; Mäenpää, J.; Rane, A.; Raunio, H. Expression of xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochrome P450 forms in human adult and fetal liver. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 48, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouritaki, S.B.; Manro, J.R.; Marsh, S.A.; Stevens, J.C.; Rettie, A.E.; McCarver, D.G.; Hines, R.N. Developmental expression of human hepatic CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 308, 965–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treluyer, J.M.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E.; Alvarez, F.; Cresteil, T. Expression of CYP2D6 in developing human liver. Eur. J. Biochem. 1991, 202, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.; Marsh, S.; Zaya, M.; Regina, K.; Divakaran, K.; Le, M.; Hines, R.N. Developmental changes in human liver CYP2D6 expression. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 1587–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, M.; Naito, S. Tissue-specific mRNA expression profiles of human ATP-binding cassette and solute carrier transporter superfamilies. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2005, 20, 452–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syme, M.R.; Paxton, J.W.; Keelan, J.A. Drug Transfer and Metabolism by the Human Placenta. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 487–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prouillac, C.; Lecoeur, S. The Role of the Placenta in Fetal Exposure to Xenobiotics: Importance of Membrane Transporters and Human Models for Transfer Studies. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 1623–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceckova-Novotna, M.; Pavek, P.; Staud, F. P-glycoprotein in the placenta: Expression, localization, regulation and function. Reprod. Toxicol. 2006, 22, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vähäkangas, K.; Myllynen, P. Drug transporters in the human blood-placental barrier. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 158, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganapathy, V.; Prasad, P.D. Role of transporters in placental transfer of drugs. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 207, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.F. Structure, function and regulation of P-glycoprotein and its clinical relevance in drug disposition. Xenobiotica 2008, 38, 802–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.; Audette, M.C.; Petropoulos, S.; Gibb, W.; Matthews, S.G. Placental drug transporters and their role in fetal protection. Placenta 2012, 33, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staud, F.; Cerveny, L.; Ceckova, M. Pharmacotherapy in pregnancy; effect of ABC and SLC transporters on drug transport across the placenta and fetal drug exposure. J. Drug Target. 2012, 20, 736–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, S.; Saura, R.; Forestier, F.; Farinotti, R. P-glycoprotein expression of the human placenta during pregnancy. Placenta 2005, 26, 268–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Kingdom, J.; Baczyk, D.; Lye, S.J.; Matthews, S.G.; Gibb, W. Expression of the Multidrug Resistance P-Glycoprotein, (ABCB1 glycoprotein) in the Human Placenta Decreases with Advancing Gestation. Placenta 2006, 27, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daud, A.N.A.; Bergman, J.E.H.; Bakker, M.K.; Wang, H.; Kerstjens-Frederikse, W.S.; de Walle, H.E.K.; Groen, H.; Bos, J.H.; Hak, E.; Wilffert, B. P-Glycoprotein-Mediated Drug Interactions in Pregnancy and Changes in the Risk of Congenital Anomalies: A Case-Reference Study. Drug Saf. 2015, 38, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerb, R. Implications of genetic polymorphisms in drug transporters for pharmacotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2006, 234, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leschziner, G.D.; Andrew, T.; Pirmohamed, M.; Johnson, M.R. ABCB1 genotype and PGP expression, function and therapeutic drug response: A critical review and recommendations for future research. Pharm. J. 2007, 7, 154–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascorbi, I.; Haenisch, S. Pharmacogenetics of ATP-binding cassette transporters and clinical implications. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010, 596, 95–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ieiri, I. Functional significance of genetic polymorphisms in P-glycoprotein (MDR1, ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP, ABCG2). Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2012, 27, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noordam, R.; Aarts, N.; Hofman, A.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Stricker, B.H.; Visser, L.E. Association between genetic variation in the ABCB1 gene and switching, discontinuation, and dosage of antidepressant therapy: Results from the Rotterdam Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Fukuda, T.; Serretti, A.; Wakeno, M.; Okugawa, G.; Ikenaga, Y.; Hosoi, Y.; Takekita, Y.; Mandelli, L.; Azuma, J.; et al. ABCB1 (MDR1) gene polymorphisms are associated with the clinical response to paroxetine in patients with major depressive disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 32, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmeyer, S.; Burk, O.; von Richter, O.; Arnold, H.P.; Brockmöller, J.; Johne, A.; Cascorbi, I.; Gerloff, T.; Roots, I.; Eichelbaum, M.; et al. Functional polymorphisms of the human multidrug-resistance gene: Multiple sequence variations and correlation of one allele with P-glycoprotein expression and activity in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 3473–3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitzl, M.; Schaeffeler, E.; Hocher, B.; Slowinski, T.; Halle, H.; Eichelbaum, M.; Kaufmann, P.; Fritz, P.; Fromm, M.F.; Schwab, M. Variable expression of P-glycoprotein in the human placenta and its association with mutations of the multidrug resistance 1 gene (MDR1, ABCB1). Pharmacogenetics 2004, 14, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemauer, S.J.; Nanovskaya, T.N.; Abdel-Rahman, S.Z.; Patrikeeva, S.L.; Hankins, G.D.; Ahmed, M.S. Modulation of human placental P-glycoprotein expression and activity by MDR1 gene polymorphisms. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 79, 921–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takane, H.; Kobayashi, D.; Hirota, T.; Kigawa, J.; Terakawa, N.; Otsubo, K.; Leiri, I. Haplotype-Oriented Genetic Analysis and Functional Assessment of Promoter Variants in the MDR1 (ABCB1) Gene. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 311, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliek, B.J.B.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; van der Heiden, I.P.; Sayed-Tabatabaei, F.A.; van Duijn, C.M.; Steegers, E.R.P.; Eurocran Gene-Environment Interaction Group. Maternal medication use, carriership of the ABCB1 3435C>T polymorphism and the risk of a child with cleft lip with or without cleft palate. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2009, 149, 2088–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermann-Borst, S.A.; Isaacs, A.; Younes, Z.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; van der Heiden, I.P.; van Duyn, C.M.; Steeqers, E.A.; Steeqer-Theunissen, R.P. General maternal medication use, folic acid, the MDR1 C3435T polymorphism, and the risk of a child with a congenital heart defect. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 236, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutson, J.R.; Garcia-Bournissen, F.; Davis, A.; Koren, G. The human placental perfusion model: A systematic review and development of a model to predict in vivo transfer of therapeutic drugs. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 90, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, H.-W.; Liu, C.L.; Tsou, H.-H.; Liu, S.; Lin, K.-M.; Lu, S.C.; Hsiao, M.C.; Liu, C.F.; Chen, C.H.; Lu, M.L.; et al. CYP1A2 genetic polymorphisms are associated with early antidepressant escitalopram metabolism and adverse reactions. Pharmacogenomics 2013, 14, 1191–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.-M.; Tsou, H.-H.; Tsai, I.-J.; Hsiao, M.-C.; Hsiao, C.-F.; Liu, C.-Y.; Shen, W.W.; Tang, H.S.; Fang, C.K.; Wu, C.S.; et al. CYP1A2 genetic polymorphisms are associated with treatment response to the antidepressant paroxetine. Pharmacogenomics 2010, 11, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrazek, D.A.; Biernacka, J.M.; O’Kane, D.J.; Black, J.L.; Cunningham, J.M.; Drews, M.S.; Snyder, K.A.; Stevens, S.R. CYP2C19 variation and citalopram response. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2011, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Pollock, B.G.; Frank, E.; Cassano, G.B.; Rucci, P.; Müller, D.J.; Kennedy, J.L.; Forqione, R.N.; Kirshner, M.; Kepple, G.; et al. Effect of age, weight, and CYP2C19 genotype on escitalopram exposure. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2010, 50, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudberg, I.; Mohebi, B.; Hermann, M.; Refsum, H.; Molden, E. Impact of the ultrarapid CYP2C19*17 allele on serum concentration of escitalopram in psychiatric patients. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 83, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vos, A.; van der Weide, J.; Loovers, H.M. Association between CYP2C19*17 and metabolism of amitriptyline, citalopram and clomipramine in Dutch hospitalized patients. Pharm. J. 2011, 11, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huezo-Diaz, P.; Perroud, N.; Spencer, E.P.; Smith, R.; Sim, S.; Virding, S.; Uher, R.; Gunasinghe, C.; Gray, J.; Campbell, D.; et al. CYP2C19 genotype predicts steady state escitalopram concentration in GENDEP. J. Psychopharmacol. 2012, 26, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann, M.; Hendset, M.; Fosaas, K.; Hjerpset, M.; Refsum, H. Serum concentrations of venlafaxine and its metabolites O-desmethylvenlafaxine and N-desmethylvenlafaxine in heterozygous carriers of the CYP2D6*3,*4 or *5 allele. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 64, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, E.M.; Romkes, M.; Mulsant, B.H.; Kirshne, M.A.; Begley, A.E.; Reynolds, C.F., III; Pollock, B.G. CYP2D6 genotype and venlafaxine-XR concentrations in depressed elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 542–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawamura, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Someya, T. Effects of dosage and CYP2D6-mutated allele on plasma concentration of paroxetine. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 60, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.M.; Chiu, Y.F.; Tsai, I.J.; Chen, C.H.; Shen, W.W.; Liu, S.C.; Lu, S.C.; Liu, C.Y.; Hsiao, M.C.; Tang, H.S.; et al. ABCB1 gene polymorphisms are associated with the severity of major depressive disorder and its response to escitalopram treatment. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2011, 21, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.B.; Bousman, C.A.; Ng, C.H.; Byron, K.; Berk, M. ABCB1 polymorphism predicts escitalopram dose needed for remission in major depression. Transl. Psychiatry 2012, 2, e198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukui, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Sawamura, K.; Sugai, T.; Watanabe, J.; Inoue, Y.; Someya, T. Dose-dependent effects of the 3435 C>T genotype of ABCB1 gene on the steady-state plasma concentration of fluvoxamine in psychiatric patients. Ther. Drug Monit. 2007, 29, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikisch, G.; Eap, C.B.; Baumann, P. Citalopram enantiomers in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of ABCB1 genotyped depressive patients and clinical response: A pilot study. Pharmacol. Res. 2008, 58, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarginson, J.E.; Lazzeroni, L.C.; Ryan, H.S.; Ershoff, B.D.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Murphy, G.M., Jr. ABCB1 (MDR1) polymorphisms and antidepressant response in geriatric depression. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2010, 20, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Klerk, O.L.; Nolte, I.M.; Bet, P.M.; Bosker, F.J.; Snieder, H.; den Boer, J.A.; Bruggeman, R.; Hooqendijk, W.J.; Penninx, B.W. ABCB1 gene variants influence tolerance to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in a large sample of Dutch cases with major depressive disorder. Pharmacogenom. J. 2013, 13, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Yu, T.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, B.; Yang, F.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Feng, G.; et al. ABCB6, ABCB1 and ABCG1 genetic polymorphisms and antidepressant response of SSRIs in Chinese depressive patients. Pharmacogenomics 2013, 14, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gex-Fabry, M.; Eap, C.B.; Oneda, B.; Gervasoni, N.; Aubry, J.-M.; Bondolfi, G.; Bertschy, G. CYP2D6 and ABCB1 genetic variability: Influence on paroxetine plasma level and therapeutic response. Ther. Drug Monit. 2008, 30, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velasquez, J.C.; Goeden, N.; Bonnin, A. Placental serotonin: Implications for the developmental effects of SSRIs and maternal depression. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamers, W.H.; Virágh, S.; Wessels, A.; Moorman, A.F.; Anderson, R.H. Formation of the tricuspid valve in the human heart. Circulation 1995, 91, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebigil, C.G.; Choi, D.; Dierich, A.; Hickel, P.; Le Meur, M.; Messaddeq, N.; Launay, J.M.; Maroteaux, L. Serotonin 2B receptor is required for heart development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 9508–9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebigil, C.G.; Hickel, P.; Messaddeq, N.; Vonesch, J.-L.; Douchet, M.P.; Monassier, L.; Gyorgy, K.; Matz, R.; Andriansitohaina, R.; Manivet, P.; et al. Ablation of Serotonin 5-HT2B Receptors in Mice Leads to Abnormal Cardiac Structure and Function. Circulation 2001, 103, 2973–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, T.W. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and heart defects: Potential mechanisms for the observed associations. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011, 32, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajolle, F.; Zaffran, S.; Bonnet, D. Genetics and embryological mechanisms of congenital heart diseases. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2009, 102, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kekuda, R.; Leibach, F.H.; Furesz, T.C.; Smith, C.H.; Ganapathy, V. Polarized distribution of interleukin-1 receptors and their role in regulation of serotonin transporter in placenta. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000, 292, 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oberlander, T.F. Fetal serotonin signaling: Setting pathways for early childhood development and behavior. J. Adolesc. Heal. 2012, 51, S9–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, J.D.A.; Akerud, H.; Kaihola, H.; Pawluski, J.L.; Skalkidou, A.; Högberg, U.; Sundstrom-Poromaa, I. The effects of maternal depression and maternal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor exposure on offspring. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, J.D.A.; ÃKerud, H.; Skalkidou, A.; Kaihola, H.; Sundström-Poromaa, I. The effects of antenatal depression and antidepressant treatment on placental gene expression. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noorlander, C.W.; Ververs, F.F.T.; Nikkels, P.G.J.; van Echteld, C.J.A.; Visser, G.H.A.; Smidt, M.P. Modulation of serotonin transporter function during fetal development causes dilated heart cardiomyopathy and lifelong behavioral abnormalities. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavarone, M.S.; Shuey, D.L.; Tamir, H.; Sadler, T.W.; Lauder, J.M. Serotonin and cardiac morphogenesis in the mouse embryo. Teratology 1993, 47, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberlander, T.F.; Bonaguro, R.J.; Misri, S.; Papsdorf, M.; Ross, C.J.; Simpson, E.M. Infant serotonin transporter (SLC6A4) promoter genotype is associated with adverse neonatal outcomes after prenatal exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications. Mol. Psychiatry 2008, 13, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Smith, G.N.; Liu, X.; Holden, J.J.A. Association of MAOA, 5-HTT, and NET promoter polymorphisms with gene expression and protein activity in human placentas. Physiol. Genom. 2010, 42, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraft, J.B.; Slager, S.L.; McGrath, P.J.; Hamilton, S.P. Sequence analysis of the serotonin transporter and associations with antidepressant response. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeze, Y.; Zhou, H.; Homberg, J.R. The genetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 136, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkie, M.J.; Smith, G.; Day, R.K.; Matthews, K.; Smith, D.; Blackwood, D.; Reid, I.C.; Wolf, C.R. Polymorphisms in the SLC6A4 and HTR2A genes influence treatment outcome following antidepressant therapy. Pharmacogenom. J. 2009, 9, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishi, T.; Yoshimura, R.; Kitajima, T.; Okochi, T.; Okumura, T.; Tsunoka, T.; Yamanouchi, Y.; Kinoshita, Y.; Kawashima, K.; Naitoh, H.; et al. HTR2A is associated with SSRI response in major depressive disorder in a Japanese cohort. Neuromol. Med. 2010, 12, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, F.J.; Buervenich, S.; Charney, D.; Lipsky, R.; Rush, A.J.; Wilson, A.F.; Sorant, A.J.; Papanicolaou, G.J.; Laje, G.; Fava, M.; et al. Variation in the gene encoding the serotonin 2A receptor is associated with outcome of antidepressant treatment. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 78, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, E.J.; Slager, S.L.; Jenkins, G.D.; Reinalda, M.S.; Garriock, H.A.; Shyn, S.I.; Kraft, J.B.; Mcgrath, P.J.; Hamilton, S.P. Resequencing of serotonin-related genes and association of tagging SNPs to citalopram response. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2009, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, M.-J.; Kang, R.-H.; Ham, B.-J.; Jeong, H.-Y.; Lee, M.-S. Serotonin receptor 2A gene polymorphism (-1438A/G) and short-term treatment response to citalopram. Neuropsychobiology 2005, 52, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Fukuda, T.; Wakeno, M.; Fukuda, K.; Okugawa, G.; Ikenaga, Y.; Yamashita, M.; Takekita, Y.; Nobuhara, K.; Azuma, J.; et al. Effects of the serotonin type 2A, 3A and 3B receptor and the serotonin transporter genes on paroxetine and fluvoxamine efficacy and adverse drug reactions in depressed Japanese patients. Neuropsychobiology 2006, 53, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villafuerte, S.M.; Vallabhaneni, K.; Sliwerska, E.; McMahon, F.J.; Young, E.A.; Burmeister, M. SSRI response in depression may be influenced by SNPs in HTR1B and HTR1A. Psychiatr. Genet. 2009, 19, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, C.J.; Chen, T.J.; Yu, Y.W.; Tsai, S.J. Response to fluoxetine and serotonin 1A receptor (C-1019G) polymorphism in Taiwan Chinese major depressive disorder. Pharmacogenom. J. 2006, 6, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.W.-Y.; Tsai, S.-J.; Liou, Y.-J.; Hong, C.-J.; Chen, T.-J. Association study of two serotonin 1A receptor gene polymorphisms and fluoxetine treatment response in Chinese major depressive disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006, 16, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serretti, A.; Artioli, P.; Lorenzi, C.; Pirovano, A.; Tubazio, V.; Zanardi, R. The C(-1019)G polymorphism of the 5-HT1A gene promoter and antidepressant response in mood disorders: preliminary findings. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004, 7, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugai, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Sawamura, K.; Fukui, N.; Inoue, Y.; Someya, T. The effect of 5-hydroxytryptamine 3A and 3B receptor genes on nausea induced by paroxetine. Pharmacogenom. J. 2006, 6, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Kobayashi, D.; Murakami, Y.; Ozaki, N.; Suzuki, T.; Iwata, N.; Haraguchi, K.; Ieiri, I.; Kinukawa, N.; Hosoi, M.; et al. Genetic polymorphisms in the 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3B receptor gene and paroxetine-induced nausea. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008, 11, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ori, M.; de Lucchini, S.; Marras, G.; Nardi, I. Unraveling new roles for serotonin receptor 2B in development: Key findings from Xenopus. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2013, 57, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelb, B.D.; Chung, W.K. Complex Genetics and the Etiology of Human Congenital Heart Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaihola, H.; Olivier, J.; Poromaa, I.S.; Åkerud, H. The effect of antenatal epression and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment on nerve growth factor signaling in human placenta. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Choi, T.K.; Lee, E.; Seok, J.H.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, S.J. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism associated with short-term treatment response to venlafaxine. Neuropsychobiology 2010, 62, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlis, R.H.; Mischoulon, D.; Smoller, J.W.; Wan, Y.J.; Lamon-Fava, S.; Lin, K.M.; Rosenbaum, J.F.; Fava, M. Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and adverse effects with fluoxetine treatment. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 879–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.-Z.; Rush, A.J.; Charney, D.; Wilson, A.F.; Sorant, A.J.; Papanicolaou, G.J.; Fava, M.; Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Laje, G.; et al. Association between a functional serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism and citalopram treatment in adult outpatients with major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, E.; Tammiste, A.; Kallassalu, K.; Eller, T.; Vasar, V.; Nutt, D.J.; Metspalu, A. Serotonin transporter promoter region polymorphisms do not influence treatment response to escitalopram in patients with major depression. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009, 19, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, G.M.; Hollander, S.B.; Rodrigues, H.E.; Kremer, C.; Schatzberg, A.F. Effects of the serotonin transporter gene promoter polymorphism on mirtazapine and paroxetine efficacy and adverse events in geriatric major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smits, K.; Smits, L.; Peeters, F.; Schouten, J.; Janssen, R.; Smeets, H.; van Os, J.; Prins, M. Serotonin transporter polymorphisms and the occurrence of adverse events during treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 22, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staeker, J.; Leucht, S.; Laika, B.; Steimer, W. Polymorphisms in serotonergic pathways influence the outcome of antidepressant therapy in psychiatric inpatients. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2014, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene | SNPs | rs Numbers | MAF (%) a | Pharmacokinetics and/or Clinical Effects | Phenotype (Predicted Expression/Activity of CYP Enzymes/Transporter Proteins) | Predicted Effect on Foetal SRI Exposure b | SRIs Likely to Be Affected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasians | Asians | Africans | |||||||

| CYP1A2 | −3113G>A | rs2069521 | 3 | 8 | 11 | Increased severity of side effects of escitalopram [98] | Increased c | Reduced | Fluvoxamine, duloxetine |

| −10 + 103 T>G | rs2069526 | 3 | 8 | 12 | Increased severity of side effects of escitalopram [98] | Increased c | |||

| 832 − 249 C>T | rs4646425 | 3 | 8 | 0 | Increased severity of side effects of escitalopram [98], reduced efficacy of paroxetine [99] | Increasedc | |||

| 1253 + 81 T>C | rs4646427 | 3 | 8 | 11 | Increased severity of side effects of escitalopram [98] | Increased c | |||

| 1042 + 43 G>A | rs2472304 | 59 | 16 | 4 | Increased efficacy of paroxetine [99] | Reduced c | Increased | ||

| 1548C>T | rs2470890 | 59 | 16 | 3 | Increased efficacy of paroxetine [99] | Reducedc | |||

| CYP2C9 | *2 | rs1799853 | 11 | 0 | 4 | Reduced metabolism of fluoxetine [62,63] | Reduced d | Increased | Fluoxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine |

| *3 | rs1057910 | 7 | 3 | 2 | Reduced metabolism of fluoxetine [62,63] | Reduced d | Increased | ||

| CYP2C19 | *2 | rs4244285 | 15 | 33 | 17 | Reduced tolerance to citalopram [100] and reduced metabolism of escitalopram [101] | Reduced c,d | Increased | Citalopram *, escitalopram *, sertraline, venlafaxine |

| *3 | rs4986893 | 0 | 5 | 0 | Reduced metabolism of escitalopram [102] | Reduced d | Increased | ||

| *17 | rs12248560 | 23 | 2 | 22 | Increased metabolism of citalopram [103], escitalopram [102,104] | Increased d | Reduced | ||

| CYP2D6 | *3 | rs35742686 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Reduced metabolism of escitalopram [104], venlafaxine [105] | No activity d | Increased | Paroxetine *, fluoxetine *, venlafaxine *, fluvoxamine, sertraline |

| *4 | rs3892097 | 19 | 0 | 6 | Reduced metabolism of escitalopram [104], venlafaxine [105,106] | No activity d | Increased | ||

| *5 | whole gene deletion | 4 | 7.2 | ND | Reduced metabolism of paroxetine [107] | No activity d | Increased | ||

| *10 | rs1065852 | 20 | 52 | 9 | Reduced metabolism of paroxetine [107] | Reduced d | Increased | ||

| ABCB1 (P-gp) | 3435C>T | rs1045642 | 53 | 40 | 15 | Increased efficacy of escitalopram [108,109], venlafaxine [109], increased concentration of fluvoxamine [110], a group of antidepressants [89] | Reduced c,d | Increased | Paroxetine, fluoxetine, venlafaxine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, venlafaxine, citalopram, escitalopram |

| 1236C>T | rs1128503 | 43 | 66 | 14 | Increased concentration and side effects of antidepressants [89] | Reduced c,d | Increased | ||

| 3489 + 1573G>A | rs1882478 | 26 | 57 | 63 | Increased efficacy of escitalopram [108] | Reduced c | Increased | ||

| 2677G>T | rs2032582 | 43 | 45 | 3 | Reduced concentration and efficacy of citalopram [111], increased efficacy of paroxetine [90] | Increase or reduced c,d | Increased or reduced | ||

| 2493 + 49T>C | rs2035283 | 13 | 6 | 22 | Increased efficacy of paroxetine [112] and side effects of SSRIs [113] | Reduced c | Increased | ||

| 2481 + 24G>A | rs2235040 | 13 | 6 | 20 | Increased efficacy of paroxetine [112] and side effects of SSRIs [113] | Reduced c | Increased | ||

| 2482 − 236A>G | rs4148739 | 13 | 6 | 22 | Increased efficacy of SSRIs [114] | Reduced c | Increased | ||

| 61A>G | rs9282564 | 9 | 0 | 0 | Increased efficacy of paroxetine [115] | Reduced c | Increased | ||

| 287 − 1234G>C | rs10256836 | 29 | 15 | 8 | Reduced efficacy of escitalopram [108] | Increased c | Reduced | ||

| 2927 + 314G>A | rs28401781 | 13 | 6 | 20 | Increased efficacy of SSRIs [114] | Reduced c | Increased | ||

| Gene | SNPs | rs Numbers | MAF (%) a | Clinical Effects | Phenotype (Predicted Enzyme/Protein Expression or Activity) | Predicted Effect on CHA Risk b | SRIs Likely to Be Affected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasians | Asians | Africans | |||||||

| SLC6A4 (SERT) | SERTPR or 5-HTTLPR (S and L alleles) | rs4795541 | 40 (S) | 80 (S) | 17 (S) | S-allele: poor response to venlafaxine [147], fluoxetine [139,148], increase side effects of fluvoxamine [137], citalopram [149], escitalopram [150], paroxetine [151] and overall SSRIs [152,153] | Reduced with S allele | Increased | Fluoxetine, citalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, escitalopram, fluvoxamine |

| −1936A>G (SERTPR LA/LG allele) | rs25531 | 9 | 8 | 21 | LG allele: increased risk of side effects and poor response citalopram [149] and overall SSRIs [153] | Reduced with LG allele | Increased | ||

| 5HTT VNTR (9,10 or 12 repeat) | rs57098334 | 47 (10) | 10 (10) | 26 (10) | 12 allele was associated with higher rates of side effects of SSRIs [153] | Increased transcription with 12 repeats | Reduced | ||

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daud, A.N.A.; Bergman, J.E.H.; Kerstjens-Frederikse, W.S.; Groen, H.; Wilffert, B. The Risk of Congenital Heart Anomalies Following Prenatal Exposure to Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors—Is Pharmacogenetics the Key? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17081333

Daud ANA, Bergman JEH, Kerstjens-Frederikse WS, Groen H, Wilffert B. The Risk of Congenital Heart Anomalies Following Prenatal Exposure to Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors—Is Pharmacogenetics the Key? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016; 17(8):1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17081333

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaud, Aizati N. A., Jorieke E. H. Bergman, Wilhelmina S. Kerstjens-Frederikse, Henk Groen, and Bob Wilffert. 2016. "The Risk of Congenital Heart Anomalies Following Prenatal Exposure to Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors—Is Pharmacogenetics the Key?" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, no. 8: 1333. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17081333