Restricted Gene Flow for Gadus macrocephalus from Yellow Sea Based on Microsatellite Markers: Geographic Block of Tsushima Current

Abstract

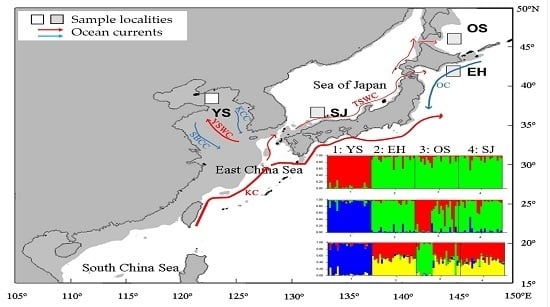

:1. Introduction

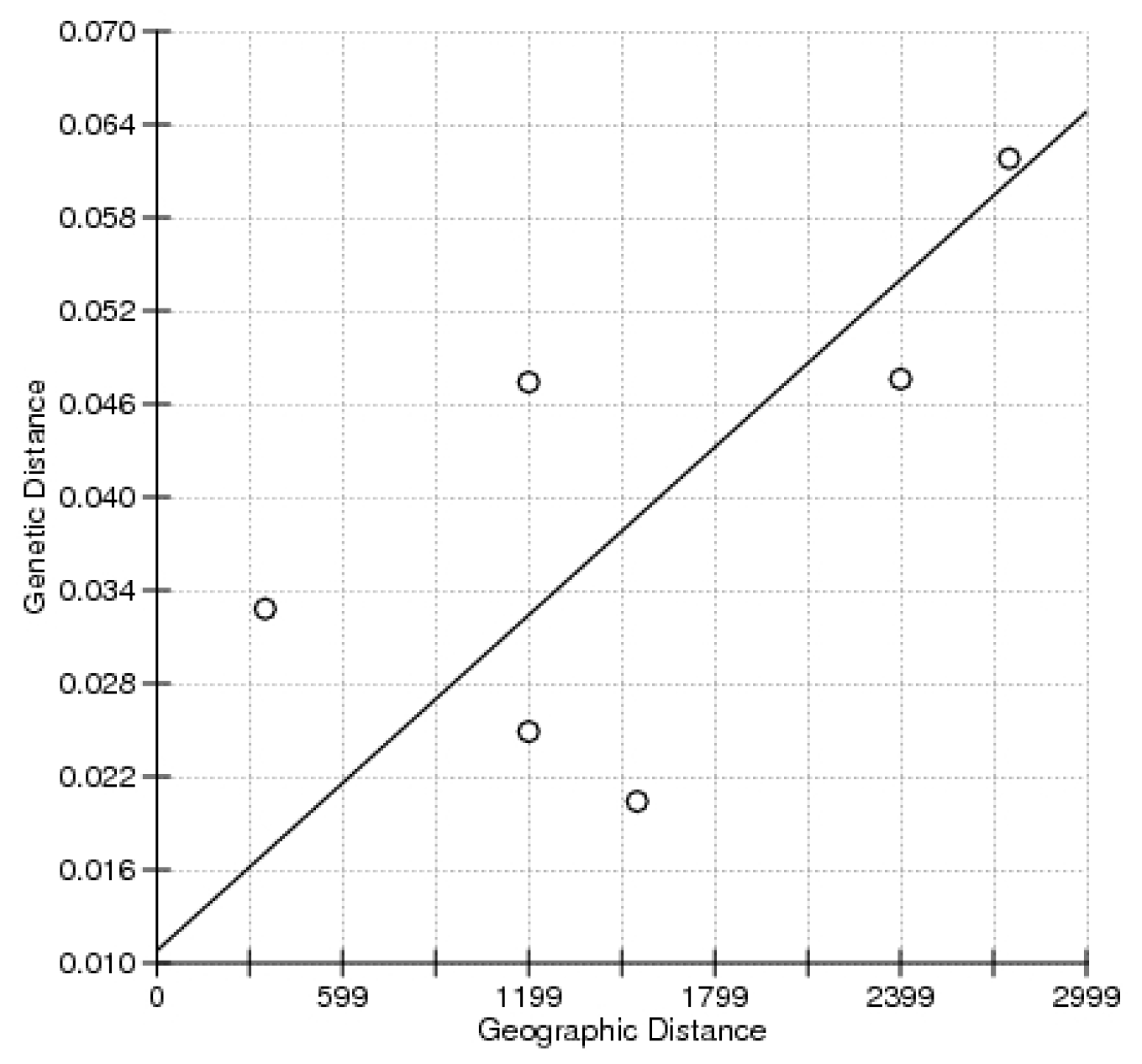

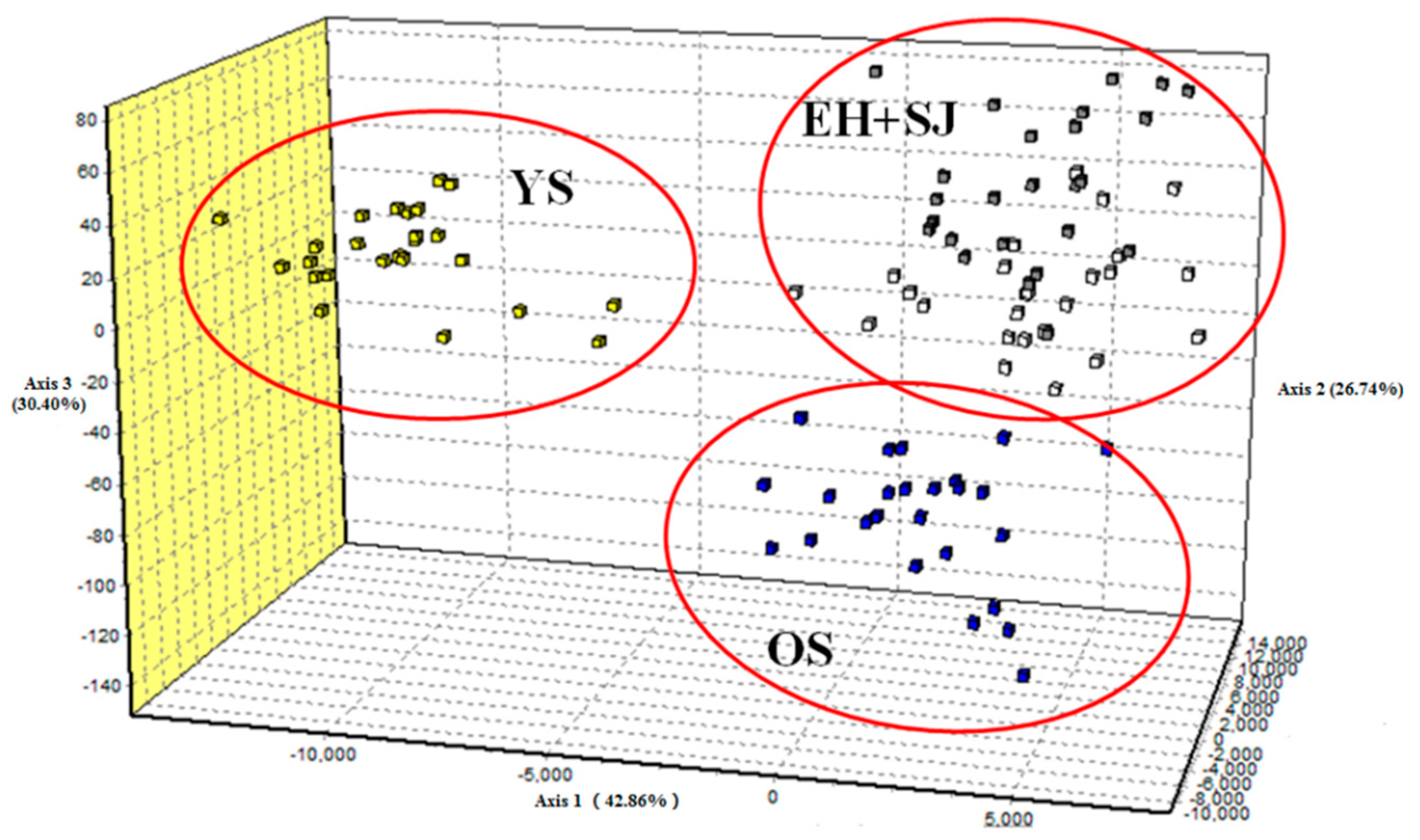

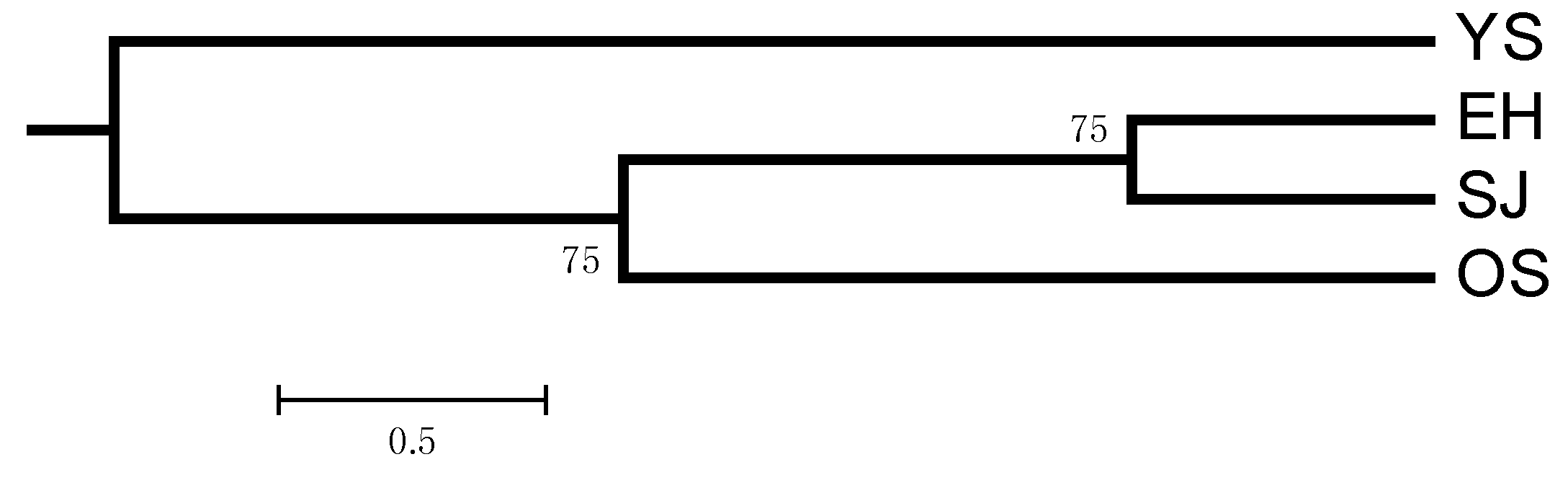

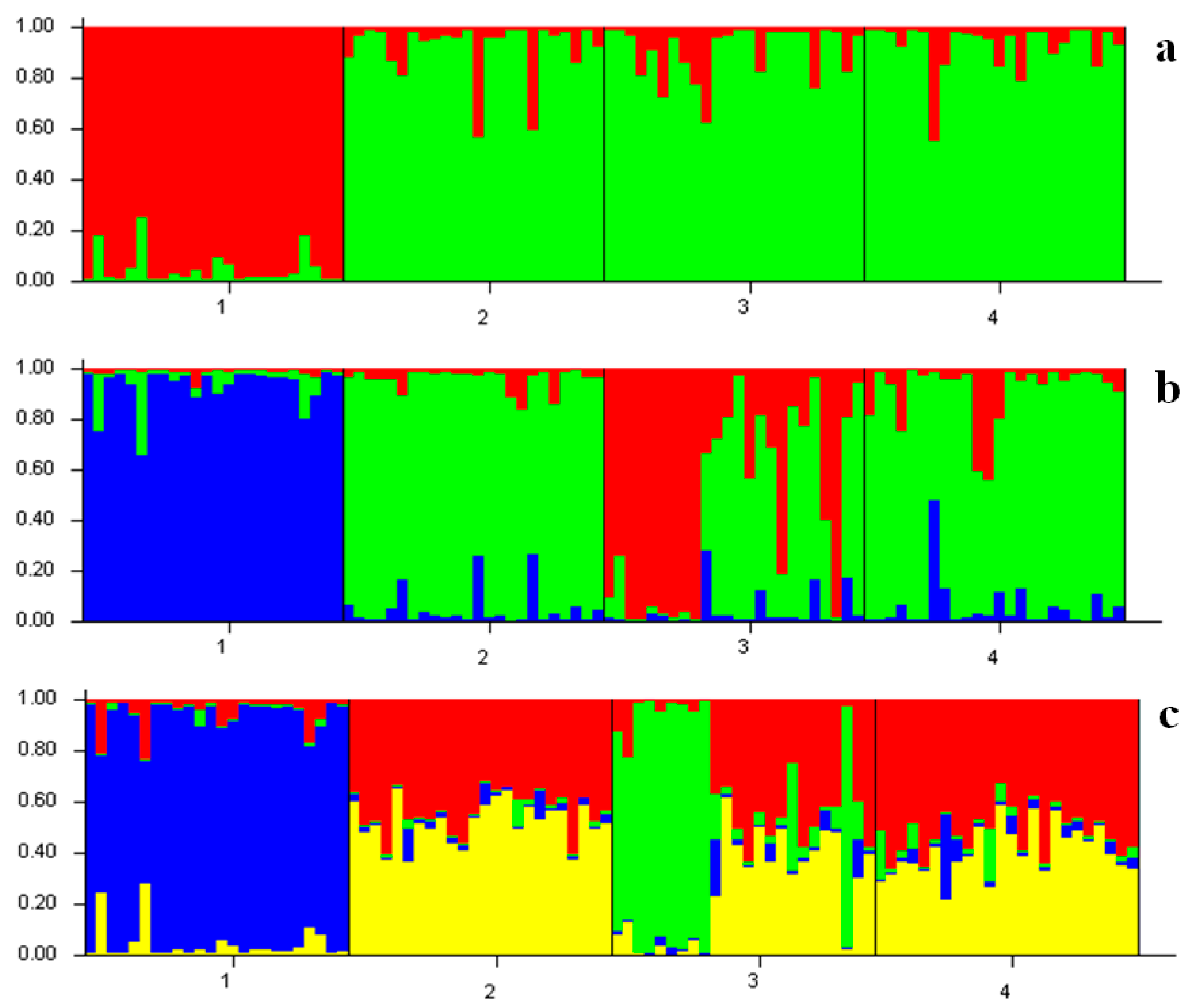

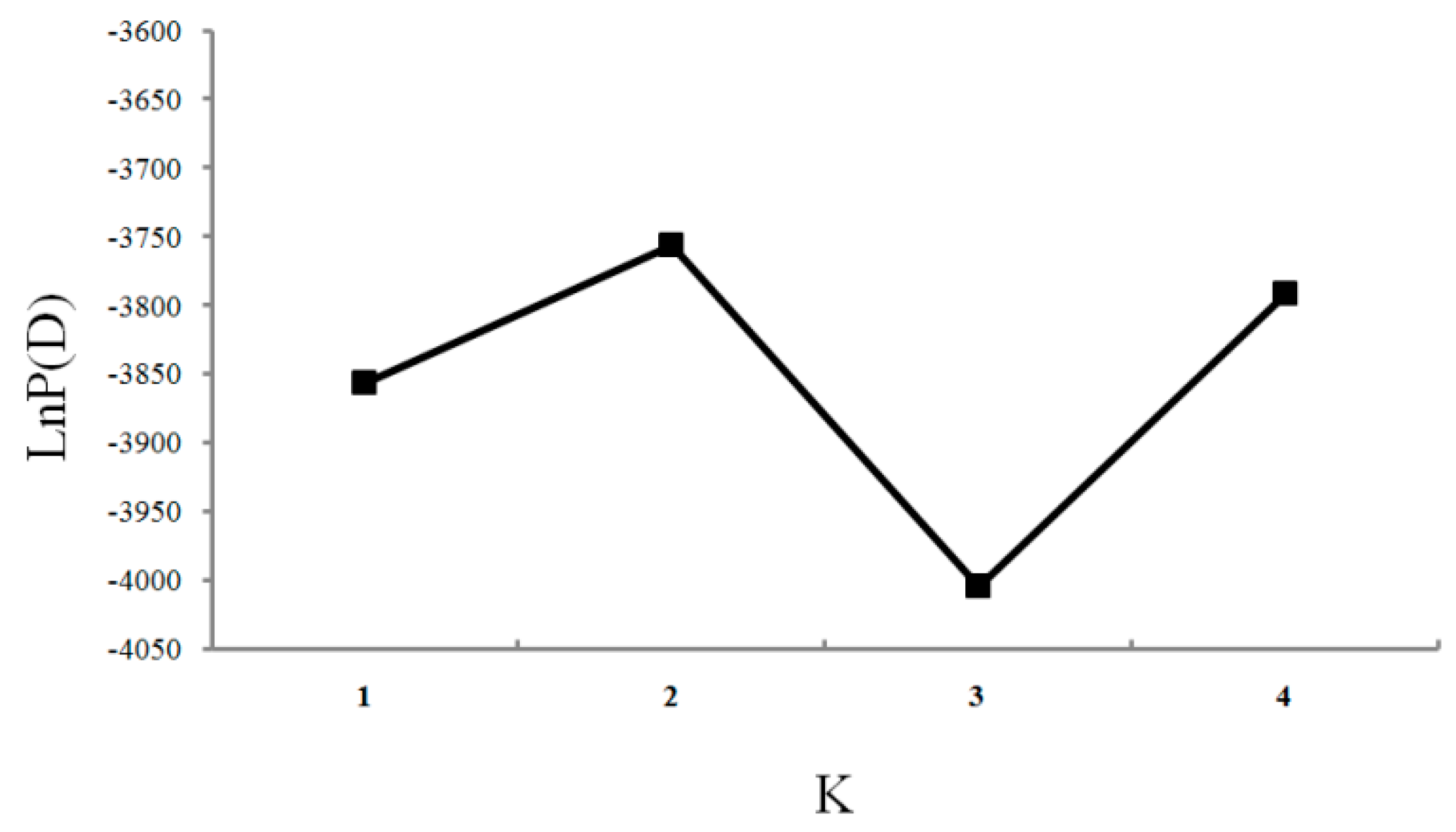

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Section

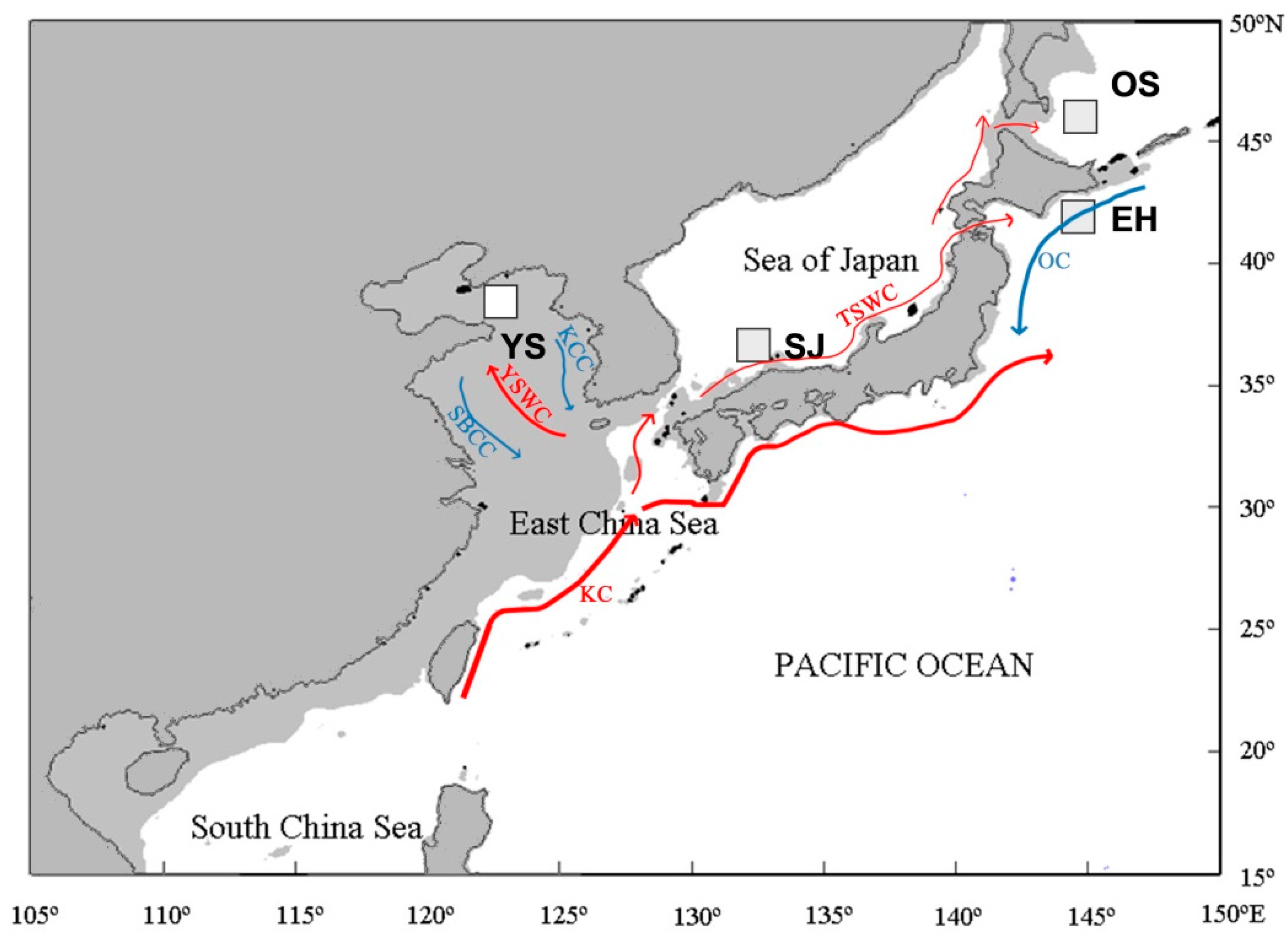

4.1. Fish Samples

4.2. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification

4.3. Data Analysis

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hart, J.L. Pacific fishes of Canada. Bull. Fish. Res. Board Can. 1973, 47, 180–730. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, W.S.; Chang, I.Z.; Kobayashi, T.; Stahl, G. Lack of genetic stock discretion in Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1987, 44, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.S.; Ye, M.Z. Exploitation and Protection of Offshore Fishery Resources for Shandong Province; Agricultural Press of China: Beijing, China, 1990; pp. 43–211. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, A.C.; Mason, J.C. A towed, self-adjusting sled sampler for demersal fish eggs and larvae. Fish. Res. 1986, 4, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, Y.; Hattori, T. Reproductive behavior of Pacific cod in captivity. Fish. Sci. 1996, 62, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Shimada, A.M.; Kimura, D.K. Seasonal movements of Pacific cod, Gadus macrocephalus, in the eastern Bering Sea and adjacent waters based on tag-recapture data. Fish. Bull. 1994, 92, 800–816. [Google Scholar]

- Tudela, S.; Garca-Marn, J.L.; Pla, C. Genetic structure of the European anchovy, Engraulis encrasicolus, in the north-west Mediterranean. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1999, 234, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utter, F.M. Biochemical genetics and fishery management: An historical perspective. J. Fish Biol. 1991, 39, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, J.A. Collapse and recovery of marine fishes. Nature 2000, 406, 882–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, R.M.; Sinclair, A.; Stefansson, G. Potential collapse of North Sea cod stocks. Nature 1997, 385, 521–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lu, Z.C.; Gao, T.X.; Yanagimoto, T.; Sakurai, Y. Remarkably low mtDNA control-region diversity and shallow population structure in Pacific cod Gadus macrocephalus. J. Fish Biol. 2010, 77, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, K.M.; Canino, M.F.; Spies, I.B.; Hauser, L. Genetic isolation by distance and localized fjord population structure in Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus): Limited effective dispersal in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2009, 66, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canino, M.F.; Spies, I.B.; Cunningham, K.M.; Hauser, L.; Grant, W.S. Multiple ice-age refugia in Pacific cod, Gadus macrocephalus. Mol. Ecol. 2010, 19, 4339–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, J.; McDowell, J.R.; Diaz-Jaimes, P.; Carlsson, J.E.; Bole, S.B.; Gold, J.R.; Graves, J. Microsatellite and mitochondrial DNA analyses of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus thynnus) population structure in the Mediterranean Sea. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 3345–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Song, N.; Gao, T.X. New evidence to genetic analysis of small yellow croaker (Larimichthys polyactis) with continuous distribution in China. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2013, 50, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yanagimoto, T.; Song, N.; Gao, T.X. Population genetic structure of chub mackerel Scomber japonicas in the Northwestern Pacific inferred from microsatellite analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2015, 42, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botstein, D.; White, R.L.; Skolnick, M.; Davis, R.W. Construct ion of a genetic linkage map in man using restriction fragment length polymorphisms. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1980, 32, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grant, W.S.; Bowen, B.W. Shallow population histories in deep evolutionary lineages of marine fishes: Insights from sardines and anchovies and lessons for conservation. J. Hered. 1998, 89, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbi, S.R. Genetic divergence, reproductive isolation, and marine speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1994, 25, 547–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderdice, D.F.; Forrester, C.R. Effects of salinity, temperature, and dissolved oxygen on the early development of Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus). J. Fish. Res. Board. Can. 1971, 28, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.I. Pacific cod of south Korean waters. Bull. Int. North Pacific Fish. Comm. 1984, 42, 116–129. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Park, Y.C.; Kim, S.S. Study of the management unit of fisheries resources by genetic method 1. Genetic similarity of Pacific cod in the North Pacific. Bull. Natl. Fish. Res. Dev. Agency 1991, 45, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, P.W.; Arkhipkin, A.I.; Al-Khairulla, H. Genetic structuring of Patagonian toothfish populations in the Southwest Atlantic Ocean: The effect of the Antarctic Polar Front and deep-water troughs as barriers to genetic exchange. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 3293–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, D.A.; Holsinger, K.E. Genetics and Conservation of Rare Plants; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, D.H.; Frankham, R. Correlation between fitness and genetic diversity. Conserv. Biol. 2003, 17, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWoody, J.A.; Avise, J.C. Microsatellite variation in marine, freshwater and anadromous fishes compared with other animals. J. Fish Biol. 2000, 56, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E.; Zardoya, R. Relative role of life-history traits and historical factors in shaping genetic population structure of sardines (Sardina pilchardus). BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemaire, C.; Allegrucci, G.; Naciri, M.; Bahri-Sfar, L.; Kara, H.; Bonhomme, F. Do discrepancies between microsatellite and allozyme variation reveal differential selection between sea and lagoon in the sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax)? Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazin, E.; Glémin, S.; Galtier, N. Population size does not influence mitochondrial genetic diversity in animals. Science 2006, 312, 570–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; Sun, F. The relationship between microsatellite slippage mutation rate and the number of repeat units. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003, 20, 2123–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Lin, L.S.; Gao, T.X.; Yanagimoto, T.; Sakurai, Y.; Grant, W.S. What maintains the central north Pacific genetic discontinuity in Pacific herring? PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canino, M.F.; Spies, I.B.; Hauser, L. Development and characterization of novel di-and tetranucleotide microsatellite markers in Pacific cod (Gadus macrocephalus). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2005, 5, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.M.; Le, K.D.; Beacham, T.D. Development of tri- and tetranucleotide repeat microsatellite loci in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua). Mol. Ecol. 2000, 9, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassam, B.J.; Caetano-Anolles, G.; Gresshoff, P.M. Fast andsensitive silver staining of DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 19, 680–683. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, M.; Rosset, F. GENEPOP: Population genetics software for exact test and ecumenism. J. Hered. 1995, 86, 248–249. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhout, V.C.; Hutchinson, W.F.; Wills, D.P.; Shipley, P. MICRO-CHECKER: Software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2004, 4, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudet, J. FSTAT (version 1.2): A computer program to calculate F-statistics. J. Hered. 1995, 86, 485–486. [Google Scholar]

- Piry, S.; Luikart, G.; Cornuet, J.M. BOTTLENECK: A computer program for detecting recent reductions in the effective population size using allele frequency data. J. Hered. 1999, 90, 502–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.Y.; Cheng, Q.Q.; Chen, X.Y. Microsatellite analysis reveals the population structure and migration patterns of Scomber japonicus (Scombridae) with continuous distribution in the East and South China Seas. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2012, 42, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luikart, G.; Allendorf, F.W.; Sherwin, B.; Cornuet, J.M. Distortion of allele frequency distributions provides a test for recent population bottlenecks. J. Hered. 1998, 12, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Laval, G.; Schneider, S. Arlequin version 3.0: An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. 2005, 1, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bohonak, A.J. IBD (isolation by distance): A program for analyses of isolation by distance. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 153–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.L.; Bohonak, A.J.; Kelley, S.T. Isolation by distance, web service. BMC Genet. 2005, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, L.; Wolf, Y.I.; Koonin, E.V.; Aravind, L. The role of lineage-specific gene family expansion in the evolution of eukaryotes. Genome Res. 2002, 12, 1048–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Peterson, D.; Peterson, N.; Stecher, G.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011, 28, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belkir, K.; Borsa, P.; Chikhi, L.; Raufaste, N.; Bonhomme, F. GENETIX 4.05, Logiciel Sous Windows TM Pour La Génétique Des Populations. Laboratoire génome, Populations, Interactions (in French); Université de Montpellier II: Montpellier, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, J.K.; Stephens, M.; Rosenberg, N.A.; Donnelly, P. Association mapping in structured populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 67, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Location | Locus | Average | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Gma102 | Gma104 | Gma107 | Gma108 | Gma109 | Gmo08 | Gmo19 | Gmo37 | ||

| The Yellow Sea (YS) | A | 12 | 15 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11.375 (2.264) |

| HE | 0.892 | 0.91 | 0.496 | 0.688 | 0.857 | 0.901 | 0.888 | 0.89 | 0.815 (0.148) | |

| HO | 0.583 | 0.958 | 0.583 | 0.708 | 0.762 | 0.826 | 0.8 | 0.792 | 0.752 (0.126) | |

| PIC | 0.861 | 0.883 | 0.472 | 0.634 | 0.817 | 0.871 | 0.853 | 0.858 | 0.781 (0.149) | |

| Eastern Hokkaido (EH) | A | 12 | 18 | 10 | 11 | 18 | 14 | 12 | 17 | 14 (3.251) |

| HE | 0.869 | 0.922 | 0.728 | 0.594 | 0.878 | 0.893 | 0.852 | 0.91 | 0.831 (0.113) | |

| HO | 0.667 | 0.917 | 0.565 | 0.625 | 0.917 | 0.875 | 0.875 | 1 | 0.805 (0.161) | |

| PIC | 0.834 | 0.896 | 0.692 | 0.56 | 0.847 | 0.864 | 0.82 | 0.881 | 0.799 (0.115) | |

| The Okhotsk Sea (OS) | A | 10 | 14 | 10 | 10 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11.75 (1.909) |

| HE | 0.804 | 0.921 | 0.862 | 0.659 | 0.915 | 0.859 | 0.891 | 0.901 | 0.852 (0.087) | |

| HO | 0.667 | 0.857 | 0.714 | 0.682 | 0.7 | 0.652 | 0.783 | 0.95 | 0.0751 (0.105) | |

| PIC | 0.758 | 0.89 | 0.812 | 0.621 | 0.883 | 0.827 | 0.859 | 0.867 | 0.815 (0.089) | |

| The Sea of Japan (SJ) | A | 11 | 24 | 13 | 14 | 21 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 15.375 (4.565) |

| HE | 0.871 | 0.957 | 0.816 | 0.629 | 0.942 | 0.848 | 0.886 | 0.848 | 0.850 (0.101) | |

| HO | 0.5 | 0.833 | 0.667 | 0.667 | 0.87 | 0.833 | 0.833 | 0.875 | 0.760 (0.134) | |

| PIC | 0.836 | 0.933 | 0.78 | 0.602 | 0.917 | 0.814 | 0.854 | 0.817 | 0.819 (0.102) | |

| Population | YS | EH | OS | SJ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YS | – | 4.1303 | 4.8946 | 5.7433 |

| EH | 0.0476 * | – | 3.0133 | 1.1149 |

| OS | 0.0618 * | 0.0328 * | – | 1.7213 |

| SJ | 0.0474 * | 0.0249 * | 0.0204 * | – |

| Gene Pools | Structure Tested | Variance (%) | F Statistics | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One pool | (YS, SJ, OS, EH) | – | – | – |

| Among populations | 3.86 | FST = 0.039 | 0.00 | |

| Within populations | 96.14 | – | – | |

| Two pools | (YS) vs. (SJ, OS, EH) | – | – | – |

| Among groups | 3.45 | FCT = 0.035 | 0.23 | |

| Within groups | 2.07 | FSC = 0.021 | 0.00 | |

| Within populations | 94.48 | FST = 0.055 | 0.00 | |

| Three pools | (YS) vs. (SJ, EH) vs. (OS) | – | – | – |

| Among groups | 1.09 | FCT = 0.011 | 0.49 | |

| Within groups | 2.95 | FSC = 0.030 | 0.74 | |

| Within populations | 95.97 | FST = 0.040 | 0.00 |

| Population | Wilcoxon Sign-Rank Test | Mode Shift a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAM | TPM | SMM | ||

| YS | 0.125 | 0.844 | 0.990 | L |

| EH | 0.680 | 1.000 | 1.000 | L |

| OS | 0.125 | 0.973 | 0.973 | L |

| SJ | 0.578 | 1.000 | 1.000 | L |

| Population | Inferred Cluster | Number of Individuals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| YS | 0.949 | 0.051 | 24 |

| EH | 0.084 | 0.916 | 24 |

| OS | 0.096 | 0.904 | 24 |

| SJ | 0.081 | 0.919 | 24 |

| ID | Sampling Sites | Date | Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| YS | The Yellow Sea | January 2005 | 24 |

| SJ | The Sea of Japan | September 2005 | 24 |

| EH | Eastern Hokkaido | January 2004 | 24 |

| OS | The Okhotsk Sea | April 2004 | 24 |

| Total | – | 96 |

| Locus | Repeat Motif | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) (F, Forward; R, Reverse) | Size Range (bp) | GenBank No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gma102 | (CTGT)17 | F: TGGTTTCATTCGGTTTGGAT R: GGGCTCAGGTAAAGCCTCTT | 221–275 | DQ027808 |

| Gma104 | (GA)8(CAGAGACA) (GAGACA)4(GACA)16 | F: AAAGAGAGCCACAGCCAGAT R: ATTCAACTGTTGGCCTCTGC | 168–230 | DQ027810 |

| Gma107 | (CTGT)12 | F: GGGAGTGGAGTACAGGGTGA R: CCATTGTTTAACATCTGGGACA | 195–243 | DQ066622 |

| Gma108 | (GACA)7 | F: AAGTCCCAACACACCAAAGC R: CTCCTCTCTCGCGCTCTTTA | 210–280 | DQ027813 |

| Gma109 | (GTCT)7G(GTCT)18 | F: CATTTTACCTTTTGCTGAGGTG R: AAATTAAATTAGTTAGATGGAAAGA | 257–373 | DQ066623 |

| Gmo08 | (GACA) | F: GCAAAACGAGATGCACAGACACC R: TGGGGGAGGCATCTGTCATTCA | 110–205 | AFI159238 |

| Gmo19 | (GACA) | F: CACAGTGAAGTGAACCCACTG R: GTCTTGCCTGTAAGTCAGCTTG | 120–220 | AFI159232 |

| Gmo37 | (GACA) | F: GGCCAATGTTTCATAACTCT R: CGTGGGATACATGGGTACT | 220–290 | AFI159237 |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, N.; Liu, M.; Yanagimoto, T.; Sakurai, Y.; Han, Z.-Q.; Gao, T.-X. Restricted Gene Flow for Gadus macrocephalus from Yellow Sea Based on Microsatellite Markers: Geographic Block of Tsushima Current. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17040467

Song N, Liu M, Yanagimoto T, Sakurai Y, Han Z-Q, Gao T-X. Restricted Gene Flow for Gadus macrocephalus from Yellow Sea Based on Microsatellite Markers: Geographic Block of Tsushima Current. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016; 17(4):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17040467

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Na, Ming Liu, Takashi Yanagimoto, Yasunori Sakurai, Zhi-Qiang Han, and Tian-Xiang Gao. 2016. "Restricted Gene Flow for Gadus macrocephalus from Yellow Sea Based on Microsatellite Markers: Geographic Block of Tsushima Current" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, no. 4: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17040467