Notch Signaling in Pancreatic Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

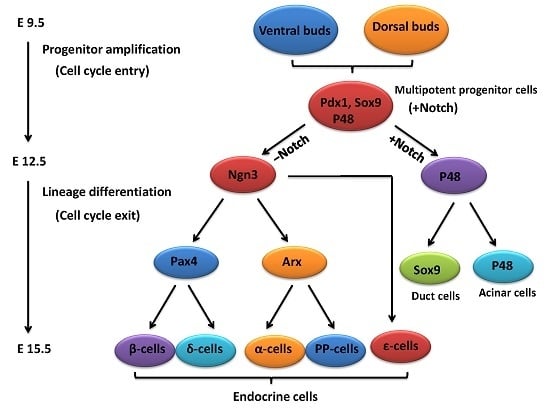

2. An Outline of Pancreatic Development

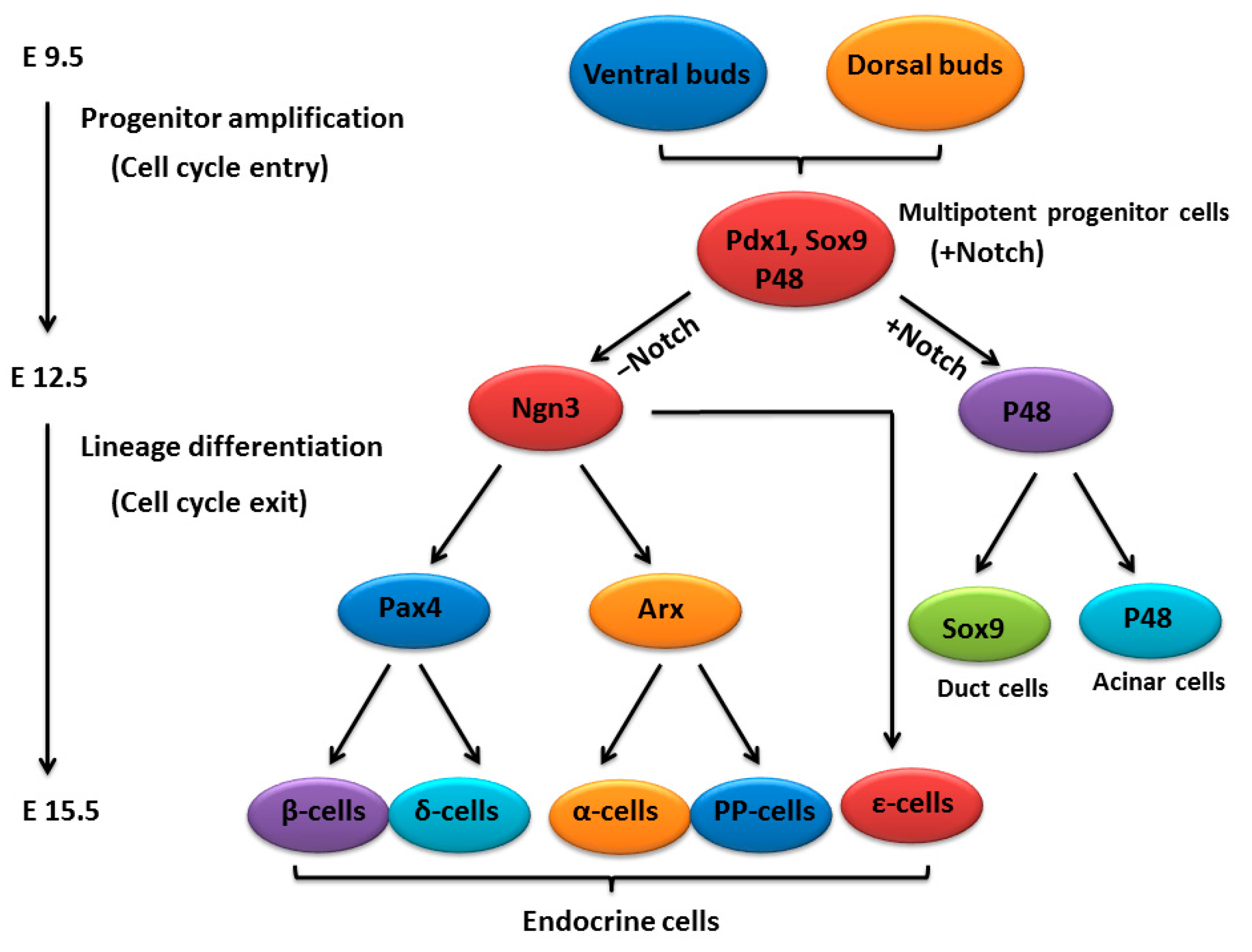

3. An Overview of the Notch Signaling Cascade

4. Notch Signaling Pathway in the Pancreas

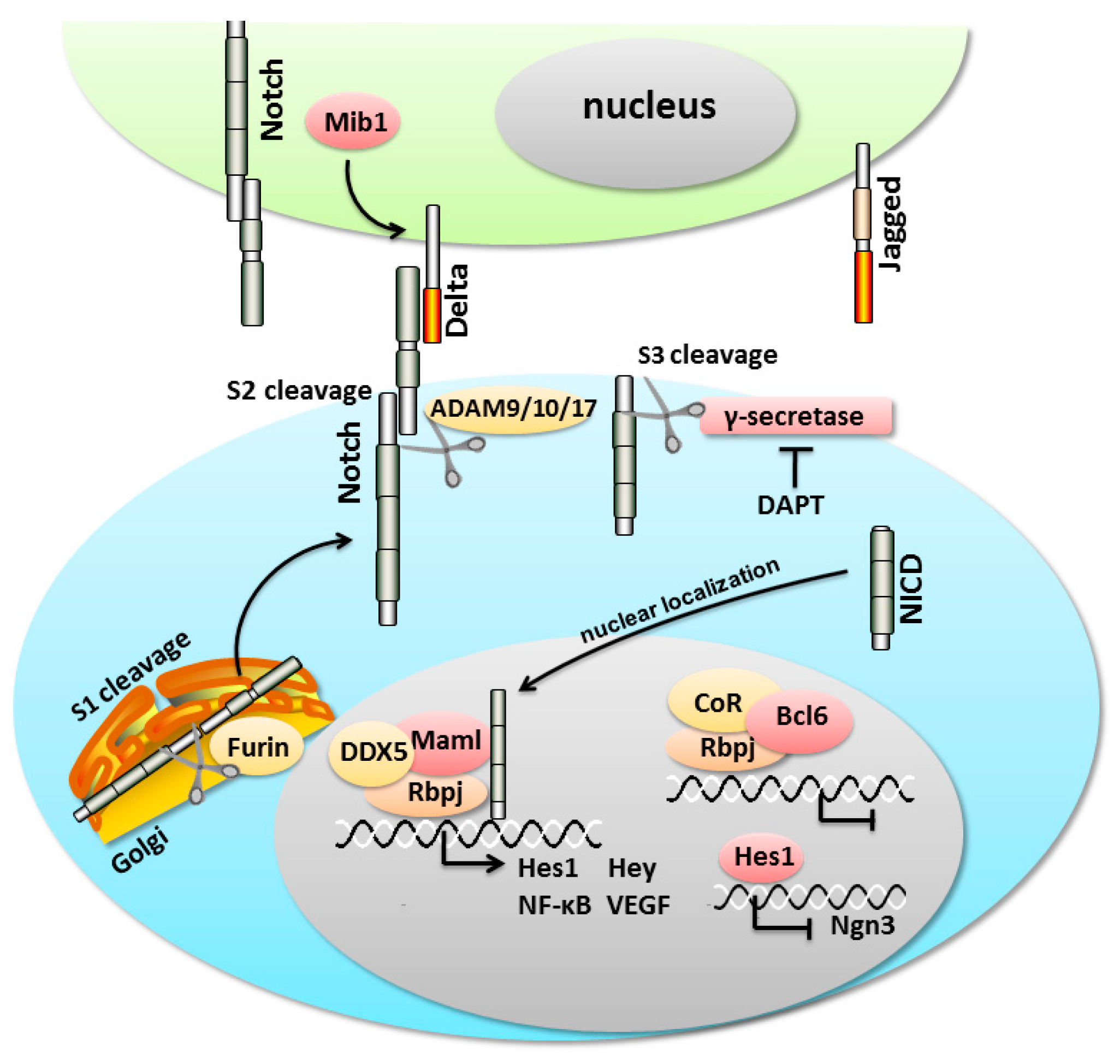

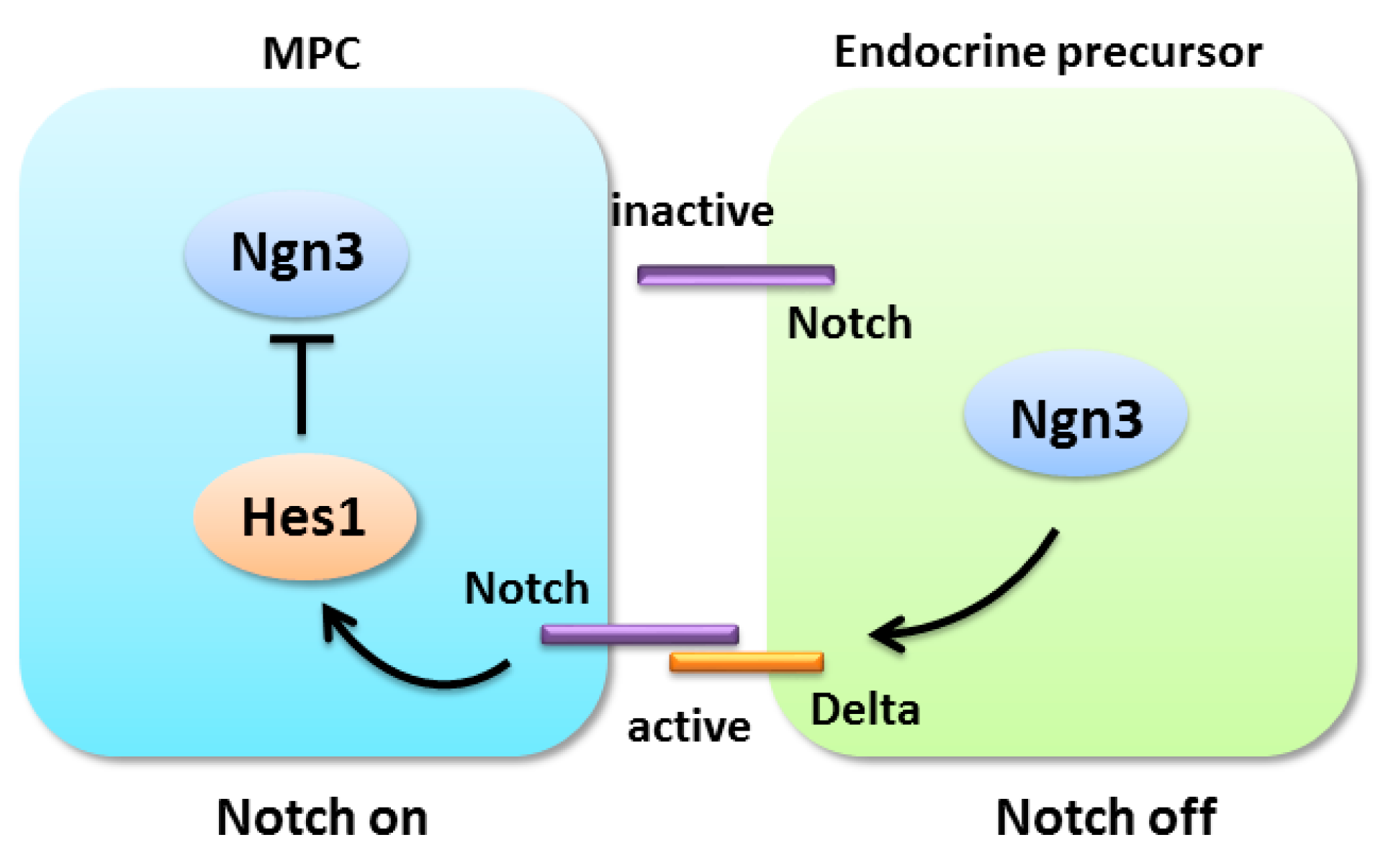

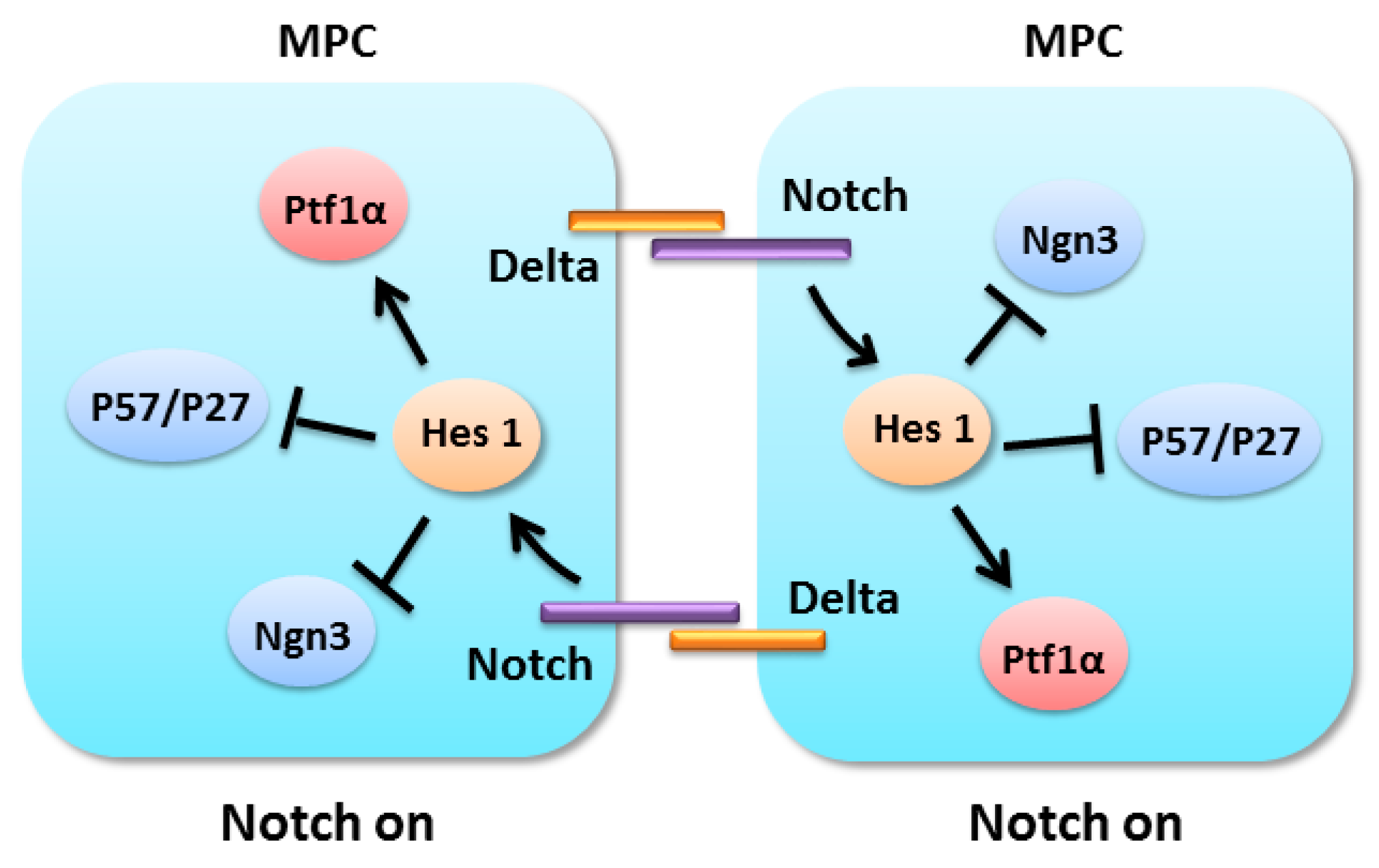

4.1. Notch Signaling in Pancreatic Progenitor Cell Differentiation

4.2. Notch Signaling in Pancreatic Progenitors Maintenance

4.3. Notch Signaling in Adult Pancreatic Cell Plasticity

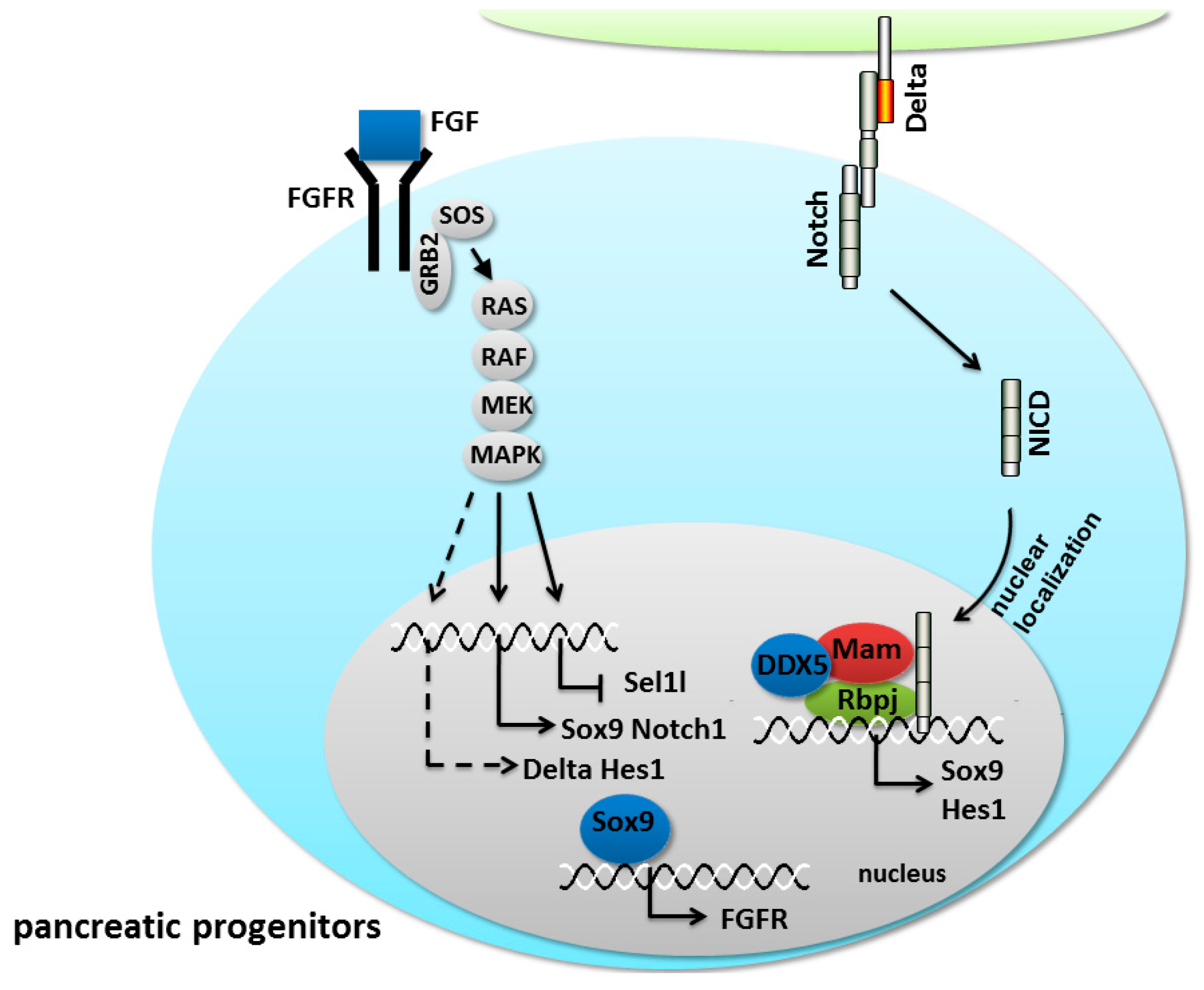

5. The Crosstalk between Notch Signaling and the Wingless and INT-1 (Wnt)/Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) Pathway in the Pancreas

5.1. Notch/Wnt Crosstalk

5.2. Notch/FGF Crosstalk

6. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Artavanis-Tsakonas, S.; Matsuno, K.; Fortini, M.E. Notch signaling. Science 1995, 268, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, S. Notch signalling in drosophila: Three ways to use a pathway. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998, 9, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buono, K.D.; Robinson, G.W.; Martin, C.; Shi, S.; Stanley, P.; Tanigaki, K.; Honjo, T.; Hennighausen, L. The canonical Notch/Rbp-j signaling pathway controls the balance of cell lineages in mammary epithelium during pregnancy. Dev. Biol. 2006, 293, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopan, R.; Ilagan, M.X. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: Unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell 2009, 137, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yugawa, T.; Nishino, K.; Ohno, S.; Nakahara, T.; Fujita, M.; Goshima, N.; Umezawa, A.; Kiyono, T. Noncanonical Notch signaling limits self-renewal of human epithelial and induced pluripotent stem cells through rock activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2013, 33, 4434–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layden, M.J.; Martindale, M.Q. Non-canonical Notch signaling represents an ancestral mechanism to regulate neural differentiation. Evodevo 2014, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezeron, G.; Millen, K.; Boukhatmi, H.; Bray, S. Notch directly regulates the cell morphogenesis genes Reck, talin and trio in adult muscle progenitors. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 4634–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Back, W.; Zhou, J.X.; Brusch, L. On the role of lateral stabilization during early patterning in the pancreas. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20120766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Shin, Y.K.; Kim, B.J.; Egan, J.M. Notch signaling in pancreatic endocrine cell and diabetes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 392, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Caignec, C. Human diseases and Notch receptors. Med. Sci. 2011, 27, 593–595. [Google Scholar]

- Polychronidou, E.; Vlachakis, D.; Vlamos, P.; Baumann, M.; Kossida, S. Notch signaling and ageing. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 822, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bi, P.; Kuang, S. Notch signaling as a novel regulator of metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 26, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grishina, I.B. Mini-review: Does Notch promote or suppress cancer? New findings and old controversies. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 2015, 3, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murtaugh, L.C.; Stanger, B.Z.; Kwan, K.M.; Melton, D.A. Notch signaling controls multiple steps of pancreatic differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14920–14925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, A.L.; Li, S.; Jones, K.; Melton, D.A. Notch signaling reveals developmental plasticity of pax4(+) pancreatic endocrine progenitors and shunts them to a duct fate. Mech. Dev. 2007, 124, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afelik, S.; Jensen, J. Notch signaling in the pancreas: Patterning and cell fate specification. Dev. Biol. 2013, 2, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hald, J.; Hjorth, J.P.; German, M.S.; Madsen, O.D.; Serup, P.; Jensen, J. Activated Notch1 prevents differentiation of pancreatic acinar cells and attenuate endocrine development. Dev. Biol. 2003, 260, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahnfelt-Ronne, J.; Hald, J.; Bodker, A.; Yassin, H.; Serup, P.; Hecksher-Sorensen, J. Preservation of proliferating pancreatic progenitor cells by δ-Notch signaling in the embryonic chicken pancreas. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zecchin, E.; Filippi, A.; Biemar, F.; Tiso, N.; Pauls, S.; Ellertsdottir, E.; Gnugge, L.; Bortolussi, M.; Driever, W.; Argenton, F. Distinct δ and jagged genes control sequential segregation of pancreatic cell types from precursor pools in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 2007, 301, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakhai, H.; Siveke, J.T.; Klein, B.; Mendoza-Torres, L.; Mazur, P.K.; Algul, H.; Radtke, F.; Strobl, L.; Zimber-Strobl, U.; Schmid, R.M. Conditional ablation of Notch signaling in pancreatic development. Development 2008, 135, 2757–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahnfelt-Ronne, J.; Jorgensen, M.C.; Klinck, R.; Jensen, J.N.; Fuchtbauer, E.M.; Deering, T.; MacDonald, R.J.; Wright, C.V.; Madsen, O.D.; Serup, P. Ptf1a-mediated control of Dll1 reveals an alternative to the lateral inhibition mechanism. Development 2012, 139, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, H.P.; Kopp, J.L.; Sandhu, M.; Dubois, C.L.; Seymour, P.A.; Grapin-Botton, A.; Sander, M. A Notch-dependent molecular circuitry initiates pancreatic endocrine and ductal cell differentiation. Development 2012, 139, 2488–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimajiri, Y.; Kosaka, Y.; Scheel, D.W.; Lynn, F.C.; Kishimoto, N.; Wang, J.; Zhao, S.; German, M.S. A mouse model for monitoring islet cell genesis and developing therapies for diabetes. Dis. Model. Mech. 2011, 4, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afelik, S.; Qu, X.; Hasrouni, E.; Bukys, M.A.; Deering, T.; Nieuwoudt, S.; Rogers, W.; Macdonald, R.J.; Jensen, J. Notch-mediated patterning and cell fate allocation of pancreatic progenitor cells. Development 2012, 139, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosokawa, S.; Furuyama, K.; Horiguchi, M.; Aoyama, Y.; Tsuboi, K.; Sakikubo, M.; Goto, T.; Hirata, K.; Tanabe, W.; Nakano, Y.; et al. Impact of Sox9 dosage and Hes1-mediated Notch signaling in controlling the plasticity of adult pancreatic duct cells in mice. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ninov, N.; Borius, M.; Stainier, D.Y. Different levels of Notch signaling regulate quiescence, renewal and differentiation in pancreatic endocrine progenitors. Development 2012, 139, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhanot, U.; Kohntop, R.; Hasel, C.; Moller, P. Evidence of Notch pathway activation in the ectatic ducts of chronic pancreatitis. J. Pathol. 2008, 214, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, A.V.; Rooman, I.; Reichert, M.; de Medts, N.; Bouwens, L.; Rustgi, A.K.; Real, F.X. Adult pancreatic acinar cells dedifferentiate to an embryonic progenitor phenotype with concomitant activation of a senescence programme that is present in chronic pancreatitis. Gut 2011, 60, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chetty, R.; Serra, S.; Salahshor, S.; Alsaad, K.; Shih, W.; Blaszyk, H.; Woodgett, J.R.; Tsao, M.S. Expression of wnt-signaling pathway proteins in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: A tissue microarray analysis. Hum. Pathol. 2006, 37, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.L.; Vuguin, P.M. Determinants of pancreatic islet development in mice and men: A focus on the role of transcription factors. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 2012, 77, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, P.A.; Shih, H.P.; Patel, N.A.; Freude, K.K.; Xie, R.; Lim, C.J.; Sander, M. A Sox9/FGF feed-forward loop maintains pancreatic organ identity. Development 2012, 139, 3363–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe-Coote, S.A.; Louw, J.; Poerstamper, H.M.; Du Toit, D.F. Do the pancreatic primordial buds in embryogenesis have the potential to produce all pancreatic endocrine cells? Med. Hypotheses 1990, 31, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, P.L. Developmental biology of the pancreas. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 40, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, P.L. Adult insulin- and glucagon-producing cells differentiate from two independent cell lineages. Development 2000, 127, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Teitelman, G.; Alpert, S.; Polak, J.M.; Martinez, A.; Hanahan, D. Precursor cells of mouse endocrine pancreas coexpress insulin, glucagon and the neuronal proteins tyrosine hydroxylase and neuropeptide y, but not pancreatic polypeptide. Development 1993, 118, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kemp, J.D.; Walther, B.T.; Rutter, W.J. Protein synthesis during the secondary developmental transition of the embryonic rat pancreas. J. Biol. Chem. 1972, 247, 3941–3952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Kilic, G.; Aydin, M.; Burke, Z.; Oliver, G.; Sosa-Pineda, B. Prox1 activity controls pancreas morphogenesis and participates in the production of “secondary transition” pancreatic endocrine cells. Dev. Biol. 2005, 286, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouwens, L.; Rooman, I. Regulation of pancreatic β-cell mass. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1255–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offield, M.F.; Jetton, T.L.; Labosky, P.A.; Ray, M.; Stein, R.W.; Magnuson, M.A.; Hogan, B.L.; Wright, C.V. Pdx-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development 1996, 122, 983–995. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arda, H.E.; Benitez, C.M.; Kim, S.K. Gene regulatory networks governing pancreas development. Dev. Cell 2013, 25, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonal, C.; Herrera, P.L. Genes controlling pancreas ontogeny. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2008, 52, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; MacFarlane, W.M.; Tadayyon, M.; Arch, J.R.; James, R.F.; Docherty, K. Insulin stimulates pancreatic-duodenal homoeobox factor-1 (PDX1) DNA-binding activity and insulin promoter activity in pancreatic β cells. Biochem. J. 1999, 344, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, F.C.; Smith, S.B.; Wilson, M.E.; Yang, K.Y.; Nekrep, N.; German, M.S. Sox9 coordinates a transcriptional network in pancreatic progenitor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 10500–10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hald, J.; Sprinkel, A.E.; Ray, M.; Serup, P.; Wright, C.; Madsen, O.D. Generation and characterization of Ptf1a antiserum and localization of Ptf1a in relation to Nkx6.1 and Pdx1 during the earliest stages of mouse pancreas development. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2008, 56, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, P.A.; Freude, K.K.; Tran, M.N.; Mayes, E.E.; Jensen, J.; Kist, R.; Scherer, G.; Sander, M. Sox9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor cell pool. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1865–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodolosse, A.; Chalaux, E.; Adell, T.; Hagege, H.; Skoudy, A.; Real, F.X. Ptf1α/p48 transcription factor couples proliferation and differentiation in the exocrine pancreas [corrected]. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 937–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradwohl, G.; Dierich, A.; LeMeur, M.; Guillemot, F. Neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beucher, A.; Gjernes, E.; Collin, C.; Courtney, M.; Meunier, A.; Collombat, P.; Gradwohl, G. The homeodomain-containing transcription factors Arx and Pax4 control enteroendocrine subtype specification in mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juhl, K.; Sarkar, S.A.; Wong, R.; Jensen, J.; Hutton, J.C. Mouse pancreatic endocrine cell transcriptome defined in the embryonic Ngn3-null mouse. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2755–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Rane, S.G. The Cdk4-E2F1 pathway regulates early pancreas development by targeting PDX1+ progenitors and Ngn3+ endocrine precursors. Development 2011, 138, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccand, J.; Meunier, A.; Merle, C.; Jia, Z.; Barnier, J.V.; Gradwohl, G. Pak3 promotes cell cycle exit and differentiation of β-cells in the embryonic pancreas and is necessary to maintain glucose homeostasis in adult mice. Diabetes 2014, 63, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krapp, A.; Knofler, M.; Frutiger, S.; Hughes, G.J.; Hagenbuchle, O.; Wellauer, P.K. The p48 DNA-binding subunit of transcription factor Ptf1 is a new exocrine pancreas-specific basic helix-loop-helix protein. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 4317–4329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cockell, M.; Stevenson, B.J.; Strubin, M.; Hagenbuchle, O.; Wellauer, P.K. Identification of a cell-specific DNA-binding activity that interacts with a transcriptional activator of genes expressed in the acinar pancreas. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989, 9, 2464–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P.D.; Provost, E.; Leach, S.D.; Stainier, D.Y. Graded levels of Ptf1a differentially regulate endocrine and exocrine fates in the developing pancreas. Genes Dev. 2008, 22, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffer, A.E.; Freude, K.K.; Nelson, S.B.; Sander, M. Nkx6 transcription factors and Ptf1a function as antagonistic lineage determinants in multipotent pancreatic progenitors. Dev. Cell 2010, 18, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynn, F.C.; Skewes-Cox, P.; Kosaka, Y.; McManus, M.T.; Harfe, B.D.; German, M.S. Microrna expression is required for pancreatic islet cell genesis in the mouse. Diabetes 2007, 56, 2938–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latreille, M.; Hausser, J.; Stutzer, I.; Zhang, Q.; Hastoy, B.; Gargani, S.; Kerr-Conte, J.; Pattou, F.; Zavolan, M.; Esguerra, J.L.; et al. Microrna-7a regulates pancreatic β cell function. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 2722–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poy, M.N.; Hausser, J.; Trajkovski, M.; Braun, M.; Collins, S.; Rorsman, P.; Zavolan, M.; Stoffel, M. miR-375 maintains normal pancreatic α- and β-cell mass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 5813–5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Men, T.; Feng, R.C.; Li, Y.C.; Zhou, D.; Teng, C.B. miR-375 inhibits proliferation of mouse pancreatic progenitor cells by targeting YAP1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 1808–1817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Zhang, L.Q.; Ding, L.; Wang, F.; Sun, Y.J.; An, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.H.; Teng, C.B. Microrna-19b downregulates insulin 1 through targeting transcription factor neurod1. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 2592–2598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ding, L.; An, Y.; Zhang, Z.W.; Lang, Y.; Tai, S.; Guo, F.; Teng, C.B. miR-18a regulates expression of the pancreatic transcription factor Ptf1a in pancreatic progenitor and acinar cells. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Joglekar, M.V.; Parekh, V.S.; Mehta, S.; Bhonde, R.R.; Hardikar, A.A. Microrna profiling of developing and regenerating pancreas reveal post-transcriptional regulation of neurogenin3. Dev. Biol. 2007, 311, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cano, D.A.; Soria, B.; Martin, F.; Rojas, A. Transcriptional control of mammalian pancreas organogenesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 2383–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talavera-Adame, D.; Dafoe, D.C. Endothelium-derived essential signals involved in pancreas organogenesis. World J. Exp. Med. 2015, 5, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, R.J.; Purcell, K.; Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. The Notch receptor and its ligands. Trends Cell Biol. 1997, 7, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S. Notch. Curr. Biol. 2000, 10, R433–R435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logeat, F.; Bessia, C.; Brou, C.; LeBail, O.; Jarriault, S.; Seidah, N.G.; Israel, A. The Notch1 receptor is cleaved constitutively by a furin-like convertase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 8108–8112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, R.J.; Grimm, L.M.; Veraksa, A.; Banos, A.; Artavanis-Tsakonas, S. In vivo analysis of the Notch receptor s1 cleavage. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubman, O.Y.; Ilagan, M.X.; Kopan, R.; Barrick, D. Quantitative dissection of the Notch:CSL interaction: Insights into the Notch-mediated transcriptional switch. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 365, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, S.; Furriols, M. Notch pathway: Making sense of suppressor of hairless. Curr. Biol. 2001, 11, R217–R221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, S.; Bernard, F. Notch targets and their regulation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2010, 92, 253–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, A.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Furuyama, K.; Kodama, S.; Horiguchi, M.; Kuhara, T.; Koizumi, M.; Boyer, D.F.; Fujimoto, K.; Doi, R.; et al. Ectopic pancreas formation in Hes1 -knockout mice reveals plasticity of endodermal progenitors of the gut, bile duct, and pancreas. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murai, K.; Philpott, A.; Jones, P.H. Hes6 is required for the neurogenic activity of neurogenin and neurod. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, J.; Galvez, H.; Neves, J.; Abello, G.; Giraldez, F. Differential regulation of Hes/Hey genes during inner ear development. Dev. Neurobiol. 2015, 75, 703–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.C.; Smith, S.B.; Watada, H.; Lin, J.; Scheel, D.; Wang, J.; Mirmira, R.G.; German, M.S. Regulation of the pancreatic pro-endocrine gene neurogenin3. Diabetes 2001, 50, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, X.; Afelik, S.; Jensen, J.N.; Bukys, M.A.; Kobberup, S.; Schmerr, M.; Xiao, F.; Nyeng, P.; Veronica Albertoni, M.; Grapin-Botton, A.; et al. Notch-mediated post-translational control of Ngn3 protein stability regulates pancreatic patterning and cell fate commitment. Dev. Biol. 2013, 376, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakano, D.; Kato, A.; Parikh, N.; McKnight, K.; Terry, D.; Stefanovic, B.; Kato, Y. Bcl6 canalizes Notch-dependent transcription, excluding mastermind-like1 from selected target genes during left-right patterning. Dev. Cell 2010, 18, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, M.; Kim, C.H.; Palardy, G.; Oda, T.; Jiang, Y.J.; Maust, D.; Yeo, S.Y.; Lorick, K.; Wright, G.J.; Ariza-McNaughton, L.; et al. Mind bomb is a ubiquitin ligase that is essential for efficient activation of Notch signaling by δ. Dev. Cell 2003, 4, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Kobberup, S.; Jorgensen, M.C.; Kalisz, M.; Klein, T.; Kageyama, R.; Gegg, M.; Lickert, H.; Lindner, J.; Magnuson, M.A.; et al. Mind bomb 1 is required for pancreatic β-cell formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7356–7361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.; Lee, D.; Hong, S.; Park, S.G.; Song, M.R. The E3 ligase mind bomb-1 (Mib1) modulates δ-Notch signaling to control neurogenesis and gliogenesis in the developing spinal cord. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 2580–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishitani, T.; Hirao, T.; Suzuki, M.; Isoda, M.; Ishitani, S.; Harigaya, K.; Kitagawa, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Itoh, M. Nemo-like kinase suppresses Notch signalling by interfering with formation of the Notch active transcriptional complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Tian, L.; Shen, H.; Gu, Y.; Li, J.L.; Chen, Z.; Sun, X.; You, M.J.; Wu, L. DDX5 is a positive regulator of oncogenic Notch1 signaling in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncogene 2013, 32, 4845–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, A.; Stanger, B.Z.; Gu, G. The fringe molecules induce endocrine differentiation in embryonic endoderm by activating cMyt1/cMyt3. Dev. Biol. 2006, 297, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, P.; Bergqvist, I.; Norlin, S.; Edlund, H. Mfng is dispensable for mouse pancreas development and function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009, 29, 2129–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rana, N.A.; Haltiwanger, R.S. Fringe benefits: Functional and structural impacts of O-glycosylation on the extracellular domain of Notch receptors. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2011, 21, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, H.; Haltiwanger, R.S. Significance of glycosylation in Notch signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 453, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blobel, C.P. Adams: Key components in egfr signalling and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groot, A.J.; Vooijs, M.A. The role of adams in Notch signaling. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2012, 727, 15–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Christian, L.M. The adam family: Insights into Notch proteolysis. Fly 2012, 6, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asayesh, A.; Alanentalo, T.; Khoo, N.K.; Ahlgren, U. Developmental expression of metalloproteases ADAM 9, 10, and 17 becomes restricted to divergent pancreatic compartments. Dev. Dny. 2005, 232, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyczynska, E.; Sun, D.; Yi, H.; Sehara-Fujisawa, A.; Blobel, C.P.; Zolkiewska, A. Proteolytic processing of δ-like 1 by ADAM proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tousseyn, T.; Thathiah, A.; Jorissen, E.; Raemaekers, T.; Konietzko, U.; Reiss, K.; Maes, E.; Snellinx, A.; Serneels, L.; Nyabi, O.; et al. ADAM10, the rate-limiting protease of regulated intramembrane proteolysis of Notch and other proteins, is processed by ADAMs-9, ADAMs-15, and the γ-secretase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 11738–11747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Apelqvist, A.; Li, H.; Sommer, L.; Beatus, P.; Anderson, D.J.; Honjo, T.; Hrabe de Angelis, M.; Lendahl, U.; Edlund, H. Notch signalling controls pancreatic cell differentiation. Nature 1999, 400, 877–881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lammert, E.; Brown, J.; Melton, D.A. Notch gene expression during pancreatic organogenesis. Mech. Dev. 2000, 94, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettenhausen, B.; Hrabe de Angelis, M.; Simon, D.; Guenet, J.L.; Gossler, A. Transient and restricted expression during mouse embryogenesis of Dll1, a murine gene closely related to Drosophila δ. Development 1995, 121, 2407–2418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Golson, M.L.; le Lay, J.; Gao, N.; Bramswig, N.; Loomes, K.M.; Oakey, R.; May, C.L.; White, P.; Kaestner, K.H. Jagged1 is a competitive inhibitor of Notch signaling in the embryonic pancreas. Mech. Dev. 2009, 126, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, M.J.; Pisharath, H.; Yusuff, S.; Moore, J.C.; Siekmann, A.F.; Lawson, N.; Leach, S.D. Notch-responsive cells initiate the secondary transition in larval zebrafish pancreas. Mech. Dev. 2009, 126, 898–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovira, M.; Scott, S.G.; Liss, A.S.; Jensen, J.; Thayer, S.P.; Leach, S.D. Isolation and characterization of centroacinar/terminal ductal progenitor cells in adult mouse pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Buchler, P.; Gazdhar, A.; Giese, N.; Reber, H.A.; Hines, O.J.; Giese, T.; Buchler, M.W.; Friess, H. Pancreatic regeneration in chronic pancreatitis requires activation of the Notch signaling pathway. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2006, 10, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeyens, L.; Bonne, S.; Bos, T.; Rooman, I.; Peleman, C.; Lahoutte, T.; German, M.; Heimberg, H.; Bouwens, L. Notch signaling as gatekeeper of rat acinar-to-β-cell conversion in vitro. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1750–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.N.; Cameron, E.; Garay, M.V.; Starkey, T.W.; Gianani, R.; Jensen, J. Recapitulation of elements of embryonic development in adult mouse pancreatic regeneration. Gastroenterology 2005, 128, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikura, J.; Hosoda, K.; Iwakura, H.; Tomita, T.; Noguchi, M.; Masuzaki, H.; Tanigaki, K.; Yabe, D.; Honjo, T.; Nakao, K. Notch/Rbp-j signaling prevents premature endocrine and ductal cell differentiation in the pancreas. Cell Matab. 2006, 3, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, J.; Pedersen, E.E.; Galante, P.; Hald, J.; Heller, R.S.; Ishibashi, M.; Kageyama, R.; Guillemot, F.; Serup, P.; Madsen, O.D. Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1. Nat. Genet. 2000, 24, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sommer, L.; Ma, Q.; Anderson, D.J. Neurogenins, a novel family of atonal-related bHLH transcription factors, are putative mammalian neuronal determination genes that reveal progenitor cell heterogeneity in the developing CNS and PNS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1996, 8, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatus, P.; Lundkvist, J.; Oberg, C.; Lendahl, U. The Notch 3 intracellular domain represses Notch 1-mediated activation through hairy/enhancer of split (Hes) promoters. Development 1999, 126, 3925–3935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Esni, F.; Ghosh, B.; Biankin, A.V.; Lin, J.W.; Albert, M.A.; Yu, X.; MacDonald, R.J.; Civin, C.I.; Real, F.X.; Pack, M.A.; et al. Notch inhibits Ptf1 function and acinar cell differentiation in developing mouse and zebrafish pancreas. Development 2004, 131, 4213–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopinke, D.; Brailsford, M.; Shea, J.E.; Leavitt, R.; Scaife, C.L.; Murtaugh, L.C. Lineage tracing reveals the dynamic contribution of Hes1+ cells to the developing and adult pancreas. Development 2011, 138, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cras-Meneur, C.; Li, L.; Kopan, R.; Permutt, M.A. Presenilins, Notch dose control the fate of pancreatic endocrine progenitors during a narrow developmental window. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 2088–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopinke, D.; Brailsford, M.; Pan, F.C.; Magnuson, M.A.; Wright, C.V.; Murtaugh, L.C. Ongoing Notch signaling maintains phenotypic fidelity in the adult exocrine pancreas. Dev. Biol. 2012, 362, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, A.; Papadopoulou, S.; Edlund, H. FGF10 maintains Notch activation, stimulates proliferation, and blocks differentiation of pancreatic epithelial cells. Dev. Dny. 2003, 228, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, N.; Gesina, E.; Scheinert, P.; Bucher, P.; Grapin-Botton, A. RNA profiling and chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing reveal that Ptf1a stabilizes pancreas progenitor identity via the control of MNX1/HLXB9 and a network of other transcription factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 1189–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi, Y.; Cooper, B.; Gannon, M.; Ray, M.; MacDonald, R.J.; Wright, C.V. The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nat. Genet. 2002, 32, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, A.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Furuyama, K.; Kodama, S.; Horiguchi, M.; Kuhara, T.; Kawaguchi, M.; Terao, M.; Doi, R.; Wright, C.V.; et al. Reduction of Ptf1a gene dosage causes pancreatic hypoplasia and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2421–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norgaard, G.A.; Jensen, J.N.; Jensen, J. FGF10 signaling maintains the pancreatic progenitor cell state revealing a novel role of Notch in organ development. Dev. Biol. 2003, 264, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miralles, F.; Lamotte, L.; Couton, D.; Joshi, R.L. Interplay between FGF10 and Notch signalling is required for the self-renewal of pancreatic progenitors. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2006, 50, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, K.; Hattori, M.; Hirai, N.; Shinozuka, Y.; Hirata, H.; Kageyama, R.; Sakai, T.; Minato, N. Hes1 directly controls cell proliferation through the transcriptional repression of p27kip1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 4262–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgia, S.; Soliz, R.; Li, M.; Zhang, P.; Bhushan, A. P57 and Hes1 coordinate cell cycle exit with self-renewal of pancreatic progenitors. Dev. Biol. 2006, 298, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, E.; Li, J.; Krishnamurthy, M.; Fellows, G.F.; Goodyer, C.G.; Wang, R. Sox9 regulates endocrine cell differentiation during human fetal pancreas development. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siveke, J.T.; Lubeseder-Martellato, C.; Lee, M.; Mazur, P.K.; Nakhai, H.; Radtke, F.; Schmid, R.M. Notch signaling is required for exocrine regeneration after acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la, O.J.; Emerson, L.L.; Goodman, J.L.; Froebe, S.C.; Illum, B.E.; Curtis, A.B.; Murtaugh, L.C. Notch and Kras reprogram pancreatic acinar cells to ductal intraepithelial neoplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18907–18912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rooman, I.; de Medts, N.; Baeyens, L.; Lardon, J.; de Breuck, S.; Heimberg, H.; Bouwens, L. Expression of the Notch signaling pathway and effect on exocrine cell proliferation in adult rat pancreas. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 1206–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhi, S.; Brown, D.D. Transdifferentiation of tadpole pancreatic acinar cells to duct cells mediated by Notch and stromelysin-3. Dev. Biol. 2011, 351, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, Y.; Russ, H.A.; Knoller, S.; Ouziel-Yahalom, L.; Efrat, S. Hes-1 is involved in adaptation of adult human β-cells to proliferation in vitro. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2413–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, Y.; Russ, H.A.; Sintov, E.; Anker-Kitai, L.; Knoller, S.; Efrat, S. Redifferentiation of expanded human pancreatic β-cell-derived cells by inhibition of the Notch pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 17269–17280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minami, K.; Seino, S. Pancreatic acinar-to-β cell transdifferentiation in vitro. Front. Biosci. 2008, 13, 5824–5837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires-daSilva, A.; Sommer, R.J. The evolution of signalling pathways in animal development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, B.K.; Cash, G.; Hansen, H.; Ostler, S.; Murtaugh, L.C. Distinct requirements for β-catenin in pancreatic epithelial growth and patterning. Dev. Biol. 2014, 391, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afelik, S.; Pool, B.; Schmerr, M.; Penton, C.; Jensen, J. Wnt7b is required for epithelial progenitor growth and operates during epithelial-to-mesenchymal signaling in pancreatic development. Dev. Biol. 2015, 399, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiser, P.W.; Lau, J.; Taketo, M.M.; Herrera, P.L.; Hebrok, M. Stabilization of β-catenin impacts pancreas growth. Development 2006, 133, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaugh, L.C.; Law, A.C.; Dor, Y.; Melton, D.A. β-Catenin is essential for pancreatic acinar but not islet development. Development 2005, 132, 4663–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rulifson, I.C.; Karnik, S.K.; Heiser, P.W.; ten Berge, D.; Chen, H.; Gu, X.; Taketo, M.M.; Nusse, R.; Hebrok, M.; Kim, S.K. Wnt signaling regulates pancreatic β cell proliferation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6247–6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gui, S.; Yuan, G.; Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Xue, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Wang, D.W. Wnt3a regulates proliferation, apoptosis and function of pancreatic NIT-1 β cells via activation of IRS2/PI3K signaling. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 114, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujino, T.; Asaba, H.; Kang, M.J.; Ikeda, Y.; Sone, H.; Takada, S.; Kim, D.H.; Ioka, R.X.; Ono, M.; Tomoyori, H.; et al. Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) is essential for normal cholesterol metabolism and glucose-induced insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T. The wnt signalling pathway and diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2008, 51, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nusse, R.; Fuerer, C.; Ching, W.; Harnish, K.; Logan, C.; Zeng, A.; ten Berge, D.; Kalani, Y. Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2008, 73, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.A.; Nusse, R. Wnt proteins are self-renewal factors for mammary stem cells and promote their long-term expansion in culture. Cell Stem Cell 2010, 6, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Biehs, B.; Chiu, C.; Siebel, C.W.; Wu, Y.; Costa, M.; de Sauvage, F.J.; Klein, O.D. Opposing activities of Notch and wnt signaling regulate intestinal stem cells and gut homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2015, 11, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axelrod, J.D.; Matsuno, K.; Artavanis-Tsakonas, S.; Perrimon, N. Interaction between wingless and Notch signaling pathways mediated by dishevelled. Science 1996, 271, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collu, G.M.; Hidalgo-Sastre, A.; Acar, A.; Bayston, L.; Gildea, C.; Leverentz, M.K.; Mills, C.G.; Owens, T.W.; Meurette, O.; Dorey, K.; et al. Dishevelled limits Notch signalling through inhibition of CSL. Development 2012, 139, 4405–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strutt, D.; Johnson, R.; Cooper, K.; Bray, S. Asymmetric localization of frizzled and the determination of Notch-dependent cell fate in the drosophila eye. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capilla, A.; Johnson, R.; Daniels, M.; Benavente, M.; Bray, S.J.; Galindo, M.I. Planar cell polarity controls directional Notch signaling in the drosophila leg. Development 2012, 139, 2584–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foltz, D.R.; Santiago, M.C.; Berechid, B.E.; Nye, J.S. Glycogen synthase kinase-3β modulates Notch signaling and stability. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, P.; Brennan, K.; Sanders, P.; Balayo, T.; DasGupta, R.; Perrimon, N.; Martinez Arias, A. Notch modulates Wnt signalling by associating with Armadillo/β-catenin and regulating its transcriptional activity. Development 2005, 132, 1819–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamizu, K.; Matsunaga, T.; Uosaki, H.; Fukushima, H.; Katayama, S.; Hiraoka-Kanie, M.; Mitani, K.; Yamashita, J.K. Convergence of Notch and β-catenin signaling induces arterial fate in vascular progenitors. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, B.; Watanabe, K.; Sun, P.; Fallahi, M.; Dai, X. Chromatin effector Pygo2 mediates wnt-Notch crosstalk to suppress luminal/alveolar potential of mammary stem and basal cells. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golosow, N.; Grobstein, C. Epitheliomesenchymal interaction in pancreatic morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 1962, 4, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H.P.; Sander, M. Pancreas development ex vivo: Culturing embryonic pancreas explants on permeable culture inserts, with fibronectin-coated glass microwells, or embedded in three-dimensional matrigel. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014, 1210, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhushan, A.; Itoh, N.; Kato, S.; Thiery, J.P.; Czernichow, P.; Bellusci, S.; Scharfmann, R. FGF10 is essential for maintaining the proliferative capacity of epithelial progenitor cells during early pancreatic organogenesis. Development 2001, 128, 5109–5117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ye, F.; Duvillie, B.; Scharfmann, R. Fibroblast growth factors 7 and 10 are expressed in the human embryonic pancreatic mesenchyme and promote the proliferation of embryonic pancreatic epithelial cells. Diabetologia 2005, 48, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Francisco, A.B.; Munroe, R.J.; Schimenti, J.C.; Long, Q. SEL1L deficiency impairs growth and differentiation of pancreatic epithelial cells. BMC Dev. Biol. 2010, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeya, T.; Hayashi, S. Interplay of Notch and FGF signaling restricts cell fate and mapk activation in the drosophila trachea. Development 1999, 126, 4455–4463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mustonen, T.; Tummers, M.; Mikami, T.; Itoh, N.; Zhang, N.; Gridley, T.; Thesleff, I. Lunatic fringe, FGF, and BMP regulate the Notch pathway during epithelial morphogenesis of teeth. Dev. Biol. 2002, 248, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittes, G.K.; Galante, P.E.; Hanahan, D.; Rutter, W.J.; Debase, H.T. Lineage-specific morphogenesis in the developing pancreas: Role of mesenchymal factors. Development 1996, 122, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Blauer, M.; Sand, J.; Laukkarinen, J. Cryopreserved mouse pancreatic acinar cells from long-term explant outgrowth cultures maintain their secretory phenotype after thawing. Pancreatology 2013, 13, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dichmann, D.S.; Miller, C.P.; Jensen, J.; Scott Heller, R.; Serup, P. Expression and misexpression of members of the FGF and TGFβ families of growth factors in the developing mouse pancreas. Dev. Dyn. 2003, 226, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobberup, S.; Schmerr, M.; Dang, M.L.; Nyeng, P.; Jensen, J.N.; MacDonald, R.J.; Jensen, J. Conditional control of the differentiation competence of pancreatic endocrine and ductal cells by FGF10. Mech. Dev. 2010, 127, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvillie, B.; Heinis, M.; Stetsyuk, V. In vivo and in vitro techniques to study pancreas development and islet cell function. Endocr. Dev. 2007, 12, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hart, A.W.; Baeza, N.; Apelqvist, A.; Edlund, H. Attenuation of FGF signalling in mouse β-cells leads to diabetes. Nature 2000, 408, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duvillie, B.; Attali, M.; Bounacer, A.; Ravassard, P.; Basmaciogullari, A.; Scharfmann, R. The mesenchyme controls the timing of pancreatic β-cell differentiation. Diabetes 2006, 55, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitnis, A.; Henrique, D.; Lewis, J.; Ish-Horowicz, D.; Kintner, C. Primary neurogenesis in xenopus embryos regulated by a homologue of the drosophila neurogenic gene δ. Nature 1995, 375, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, M.; Hirata, H.; Ohtsuka, T.; Bessho, Y.; Kageyama, R. The basic helix-loop-helix genes Hesr1/Hey1 and Hesr2/Hey2 regulate maintenance of neural precursor cells in the brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44808–44815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandbarbe, L.; Bouissac, J.; Rand, M.; Hrabe de Angelis, M.; Artavanis-Tsakonas, S.; Mohier, E. δ-Notch signaling controls the generation of neurons/glia from neural stem cells in a stepwise process. Development 2003, 130, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuster-Gossler, K.; Cordes, R.; Gossler, A. Premature myogenic differentiation and depletion of progenitor cells cause severe muscle hypotrophy in δ1 mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brohl, D.; Vasyutina, E.; Czajkowski, M.T.; Griger, J.; Rassek, C.; Rahn, H.P.; Purfurst, B.; Wende, H.; Birchmeier, C. Colonization of the satellite cell niche by skeletal muscle progenitor cells depends on Notch signals. Dev. Cell 2012, 23, 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skeath, J.B. At the nexus between pattern formation and cell-type specification: The generation of individual neuroblast fates in the drosophila embryonic central nervous system. Bioessays 1999, 21, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanalkumar, R.; Dhanesh, S.B.; James, J. Non-canonical activation of Notch signaling/target genes in vertebrates. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 2957–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazave, E.; Lapebie, P.; Richards, G.S.; Brunet, F.; Ereskovsky, A.V.; Degnan, B.M.; Borchiellini, C.; Vervoort, M.; Renard, E. Origin and evolution of the Notch signalling pathway: An overview from eukaryotic genomes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2009, 9, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.-Y.; Zhai, W.-J.; Teng, C.-B. Notch Signaling in Pancreatic Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17010048

Li X-Y, Zhai W-J, Teng C-B. Notch Signaling in Pancreatic Development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2016; 17(1):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17010048

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xu-Yan, Wen-Jun Zhai, and Chun-Bo Teng. 2016. "Notch Signaling in Pancreatic Development" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17, no. 1: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17010048