Development of Microsatellite Markers in the Branched Broomrape Phelipanche ramosa L. (Pomel) and Evidence for Host-Associated Genetic Divergence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Development of Microsatellite Markers

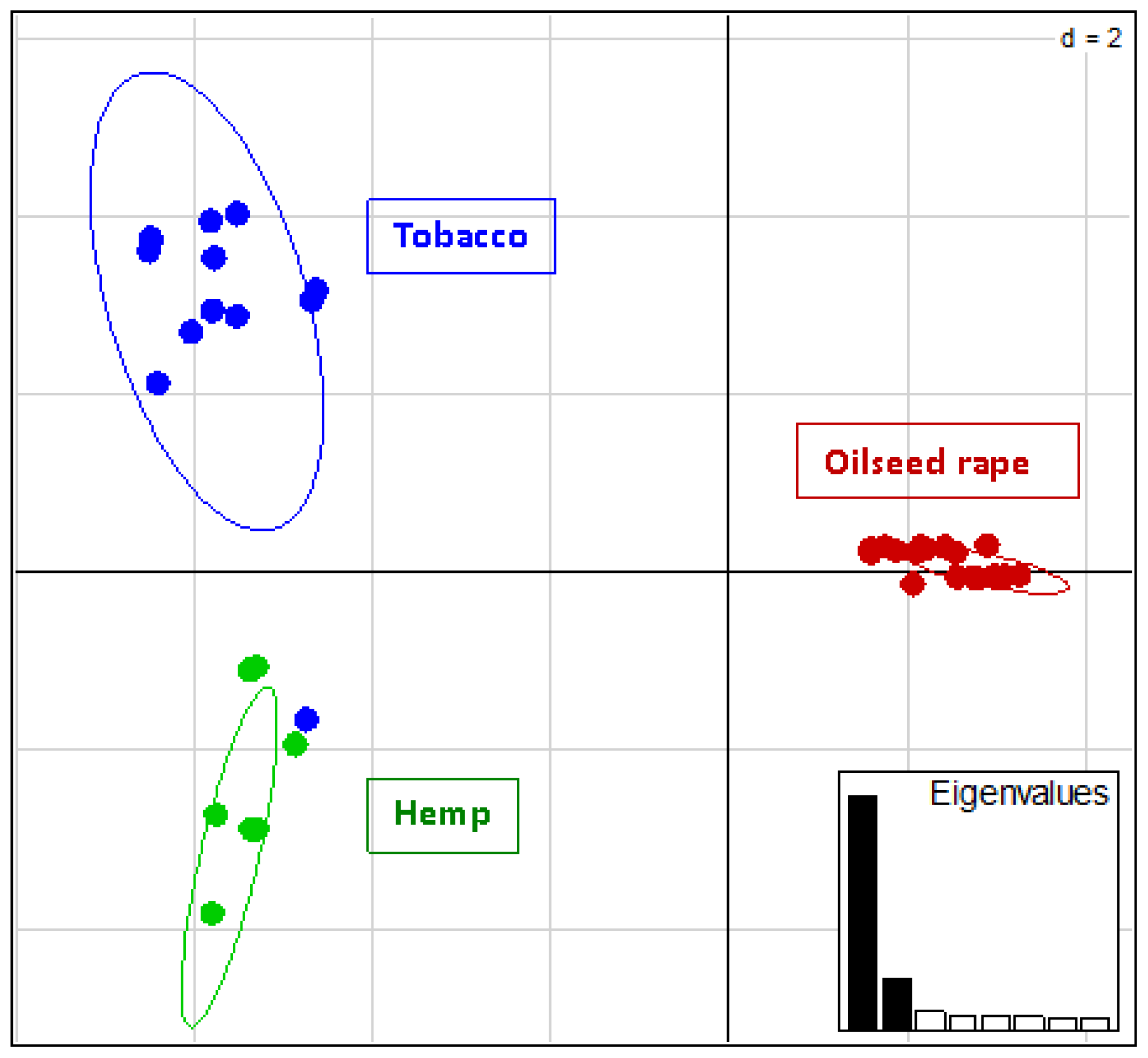

2.2. Genotyping and Population Genetics Analysis

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Plant Material and DNA Extraction

3.2. Isolation of Microsatellite Markers

3.3. DNA Amplification and Genotyping

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parker, C.; Riches, C.R. Parasitic Weeds of the World: Biology and Control; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1993; p. 332. [Google Scholar]

- Press, M.C.; Graves, J.D. Parasitic Plants; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, C. Observations on the current status of Orobanche and Striga problems worldwide. Pest Manag. Sci 2009, 65, 453–459. [Google Scholar]

- Press, M.C.; Phoenix, G.K. Impacts of parasitic plants on natural communities. New Phytol 2005, 166, 737–751. [Google Scholar]

- Benharrat, H.; Boulet, C.; Theodet, C.; Thalouarn, P. Virulence diversity among branched broomrape (O. ramosa L.) populations in France. Agron. Sustain. Dev 2005, 25, 123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Gibot-Leclerc, S.; Brault, M.; Pinochet, X.; Sallé, G. Potential role of winter rape weeds in the extension of broomrape in Poitou-Charentes. C. R. Biol 2003, 326, 645–658. [Google Scholar]

- Gibot-Leclerc, S.; Sallé, G.; Reboud, X.; Moreau, D. What are the traits to Phelipanche ramosa (L.) Pomel that contribute to the success of its biological cycle on its host Brassica napus L.? Flora 2012, 207, 512–521. [Google Scholar]

- Brault, M.; Betsou, F.; Jeune, B.; Tuquet, C.; Sallé, G. Variability of Orobanche ramosa populations in France as revealed by cross infestations and molecular markers. Environ. Exp. Bot 2007, 67, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, B.; Alfaro, C.; Torres, A.M.; Moreno, M.T.; Satovic, S.; Pujadas, A.; Rubiales, D. Genetic relationships among Orobanche species as revealed by RAPD analysis. Ann. Bot 2003, 91, 637–642. [Google Scholar]

- Vaz-Patto, M.C.; Fernandez-Aparicio, M.; Satovic, Z.; Rubiales, D. Extent and pattern of genetic differentiation within and between European populations of Phelipanche ramosa revealed by amplified fragment length polymorphism analysis. Weed Res 2009, 49, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Martos, R.; Velasco, L.; Fernandez-Escobar, J.; Fernandez-Martinez, J.M.; Perez-Vich, B. Genetic diversity of Orobanche cumana populations from Spain assessed using SSR markers. Weed Res 2013, 53, 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Délye, C.; Boucansaud, K.; Pernin, F.; le Corre, V. Variation in the gene encoding acetolactate-synthase in Lolium species and proactive detection of mutant, herbicide-resistant alleles. Weed Res 2009, 49, 326–336. [Google Scholar]

- Piednöel, M.; Aberer, I.J.; Schneeweiss, G.M.; Macas, J.; Novak, P.; Heidrun, G.; Tench, E.M.; Renner, S.S. Next-generation sequencing reveals the impact of repetitive DNA across phylogenetically closely related genomes of Orobanchaceae. Mol. Biol. Evol 2012, 29, 3601–3611. [Google Scholar]

- Schmieder, R.; Edwards, R. Quality control and preprocessing of metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 863–864. [Google Scholar]

- Meglécz, E.; Costedoat, C.; Dubut, V.; Gilles, A.; Malausa, T.; Pech, N.; Martin, J.F. QDD: A user-friendly program to select microsatellite markers and design primers from large sequencing projects. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 403–404. [Google Scholar]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in excel: Population genetic software for teaching and research—An update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar]

- Jombart, T. Adegenet: A R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar]

| Locus | Repeat motif | Primer sequences (5′-3′) | Ta (°C) | Size range (bp) | Na | Ho | He | GenBank accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phera02 | (AT)4T(AT)15 | F: CTCACACCCGGACAAAGTTC R: GGTCAATCCAGACTCGCTTC | 60 | 118–143 | 5 | 0.013 | 0.542 | SRR364824.1090 |

| Phera10 | (AT)12 | F: CCACATCAGCAACAATAGCAA R: CATGATCTTTGATAGGCACGA | 60 | 116–144 | 6 | 0.011 | 0.522 | SRR364824.897002 |

| Phera14 | (CTT)12 | F: ATGGGAACGTCTTATGGCAC R: GTGGATCCCATGGTCTTTTG | 60 | 330–336 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.442 | SRR364824.865553 |

| Phera18 | (GAT)10 | F: TGGTGAAGAAACGAACAATCA R: CATTCTCCACATTTTCCGCT | 60 | 122–131 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.481 | SRR364824.939350 |

| Phera19 | (ACC)9 | F: AGCAGTTACGGAACCACCAC R: CAGTTTCACGGGGAGAATGT | 60 | 140–143 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.308 | SRR364824.843255 |

| Phera20 | (ATT)9 | F: TCACAATACGCTCCAAGCTG R: GAGTTCACGTTGTGGGCTTT | 60 | 134–159 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.484 | SRR364824.981601 |

| Phera28 | (AT)5A(AT)9 | F: TGCGTCTGTTCTCTCAACGA R:CGGAAAGGAAGGTTCTTATTTG | 60 | 195–197 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.432 | SRR364824.879658 |

| Phera38 | (AT)11 | F: TCAGGTGAAGTGTTGCAATTAT R: GCCTTTCTTGTTCCTTGTCG | 60 | 243–261 | 6 | 0.000 | 0.601 | SRR364824.320858 |

| Phera40 | (AC)11 | F: CATCTGAGGTGCACATTACGTC R: TTTGTCATTGCTTCGTGGAG | 60 | 199–203 | 2 | 0.000 | 0.442 | SRR364824.873170 |

| Phera46 | (CAT)8(CAA)(CAT)3 | F: GTCACTTGTCCCAACATCCC R: TCTCGCCTCGCTGATAAAAT | 60 | 237–258 | 3 | 0.000 | 0.446 | SRR364824.286970 |

| Phera47 | (ACC)8 | F: GCATCAGCATCAGAAGACGA R: GGTGGTTGGTAGTTGGTTGG | 60 | 139 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | SRR364824.375211 |

| Phera53 | (ATC)2(ATT)(ATC)8 | F: CAACATCAGCGTCAACCATC R: GATCACCGACTGATGGAGGT | 60 | 128–134 | 3 | 0.011 | 0.449 | SRR364824.227061 |

| Phera59 | (TTA)7 | F: CGTTGGCCTTAAATCGCTAC R: TTGGTTTTGTGTGTGGAGGA | 60 | 304 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | SRR364824.1022037 |

| PR (Tobacco) | PO (Hemp) | GI (Oilseed rape) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus | Na | Allele sizes | Ho | He | Na | Allele sizes | Ho | He | Na | Allele sizes | Ho | He |

| Phera02 | 3 | 131/135/137 | 0.000 | 0.338 | 3 | 135/137/143 | 0.071 | 0.196 | 1 | 118 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera10 | 5 | 136/138/140/142/144 | 0.063 | 0.592 | 2 | 138/140 | 0.000 | 0.219 | 1 | 116 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera14 | 1 | 330 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 330 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 336 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera18 | 1 | 122 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 122 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 131 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera19 | 1 | 140 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 143 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 143 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera20 | 1 | 134 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 134 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 159 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera28 | 2 | 195/197 | 0.000 | 0.133 | 1 | 195 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 197 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera38 | 1 | 243 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 247 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2 | 257/259 | 0.000 | 0.142 |

| Phera40 | 1 | 203 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 203 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 199 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera46 | 1 | 237 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 237 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 258 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera53 | 1 | 134 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 134 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 131 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| SJ (Oilseed rape) | SA (Oilseed rape) | SV (Oilseed rape) | ||||||||||

| Locus | Na | Allele sizes | Ho | He | Na | Allele sizes | Ho | He | Na | Allele sizes | Ho | He |

| Phera02 | 1 | 118 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 118 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 118 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera10 | 1 | 116 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 116 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 116 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera14 | 1 | 336 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 336 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 336 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera18 | 1 | 131 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 131 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 131 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera19 | 1 | 143 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 143 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 143 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera20 | 1 | 159 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 159 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 159 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera28 | 1 | 197 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 197 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 197 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera38 | 2 | 259/261 | 0.000 | 0.271 | 4 | 255/257/259/261 | 0.000 | 0.459 | 2 | 257/259 | 0.000 | 0.133 |

| Phera40 | 1 | 199 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 199 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 199 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera46 | 2 | 255/258 | 0.000 | 0.121 | 1 | 258 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 258 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Phera53 | 1 | 131 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1 | 131 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 2 | 128/131 | 0.063 | 0.061 |

| Name | Localization | Latitude (N) | Longitude (E) | Crop |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | Priaires | 46.143 | −0.607 | Tobacco |

| PO | Pont-sur-Seine | 48.519 | 3.595 | Hemp |

| GI | Gibourne | 45.935 | −0.312 | Oilseed rape |

| SJ | Saint-Jean-d’Angély | 45.946 | −0.519 | Oilseed rape |

| SA | Savarit | 46.1142 | −0.8302 | Oilseed rape |

| SV | Savarit | 46.1142 | −0.8302 | Oilseed rape |

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Le Corre, V.; Reibel, C.; Gibot-Leclerc, S. Development of Microsatellite Markers in the Branched Broomrape Phelipanche ramosa L. (Pomel) and Evidence for Host-Associated Genetic Divergence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 994-1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15010994

Le Corre V, Reibel C, Gibot-Leclerc S. Development of Microsatellite Markers in the Branched Broomrape Phelipanche ramosa L. (Pomel) and Evidence for Host-Associated Genetic Divergence. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014; 15(1):994-1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15010994

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe Corre, Valérie, Carole Reibel, and Stéphanie Gibot-Leclerc. 2014. "Development of Microsatellite Markers in the Branched Broomrape Phelipanche ramosa L. (Pomel) and Evidence for Host-Associated Genetic Divergence" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 15, no. 1: 994-1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms15010994