Intercellular Signaling Pathway among Endothelia, Astrocytes and Neurons in Excitatory Neuronal Damage

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Role of Endothelial mPGES-1 in KA-Induced Neuronal Damage

2.1. Co-Induction of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in Brain Endothelial Cells

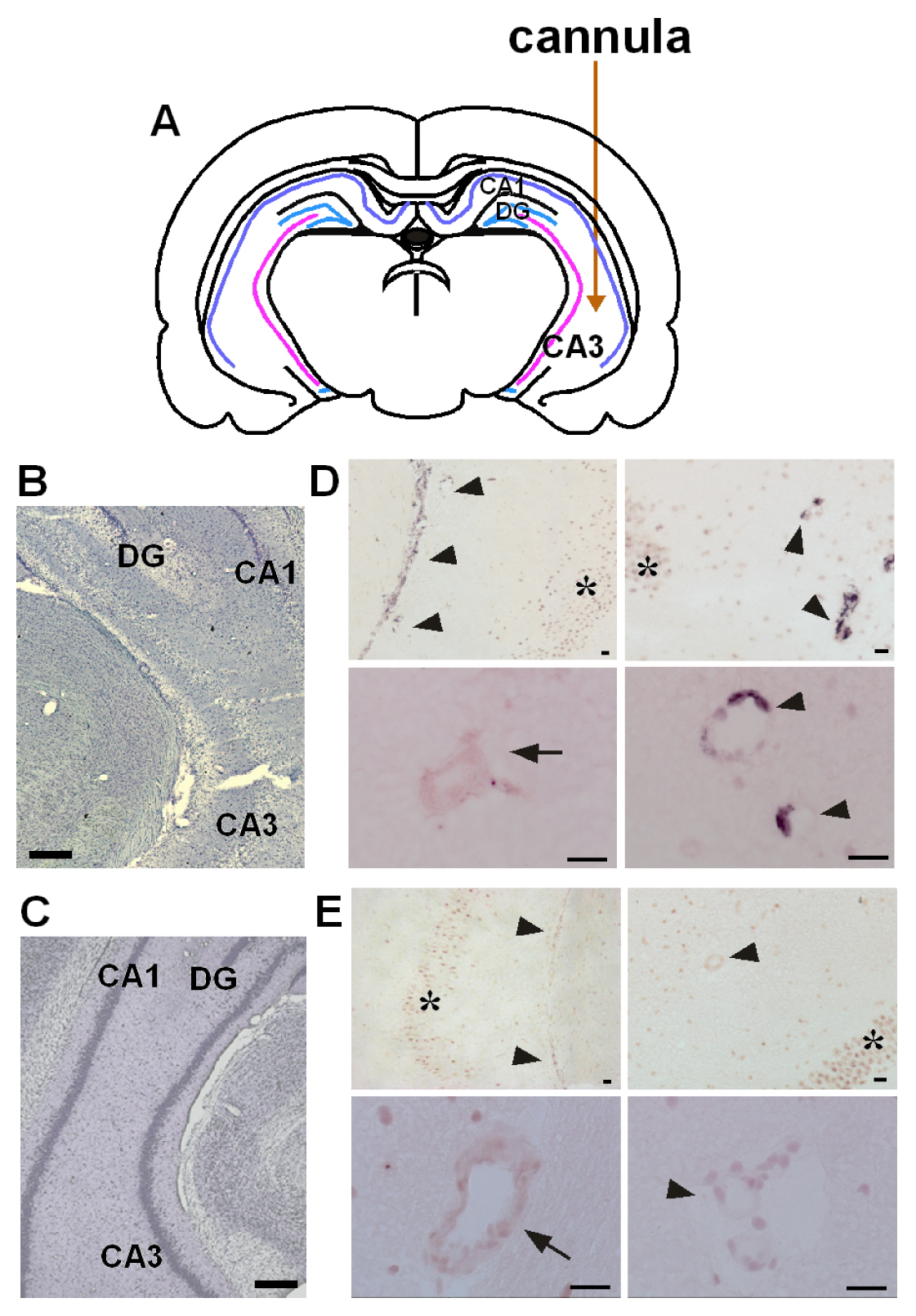

2.2. Role of Endothelial mPGES-1 in Hippocampal Neuronal Loss

3. Mechanism for Exacerbation of Neuronal Damage by Endothelial mPGES-1

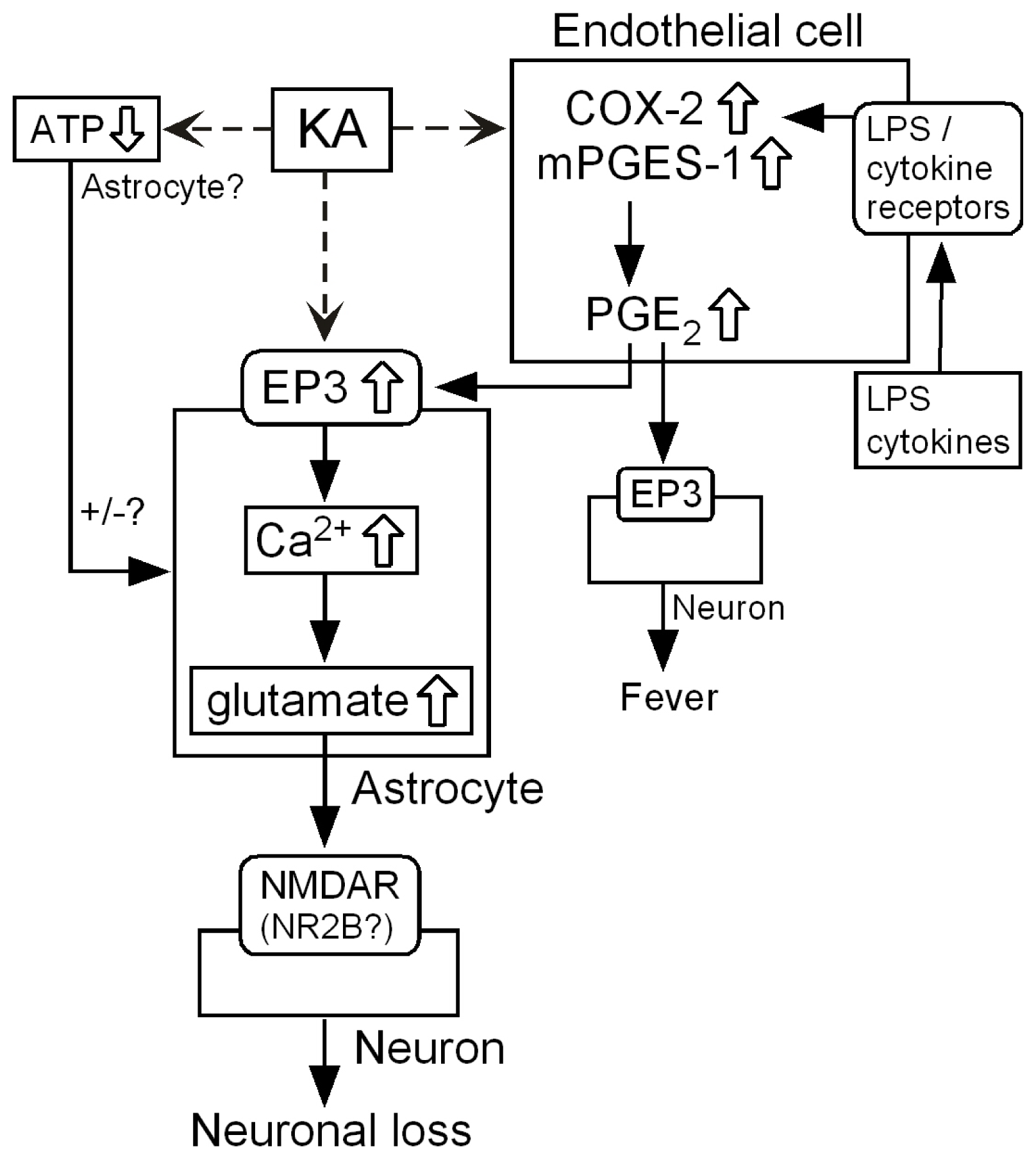

3.1. Hypothetical Mechanism for Exacerbation by mPGES-1

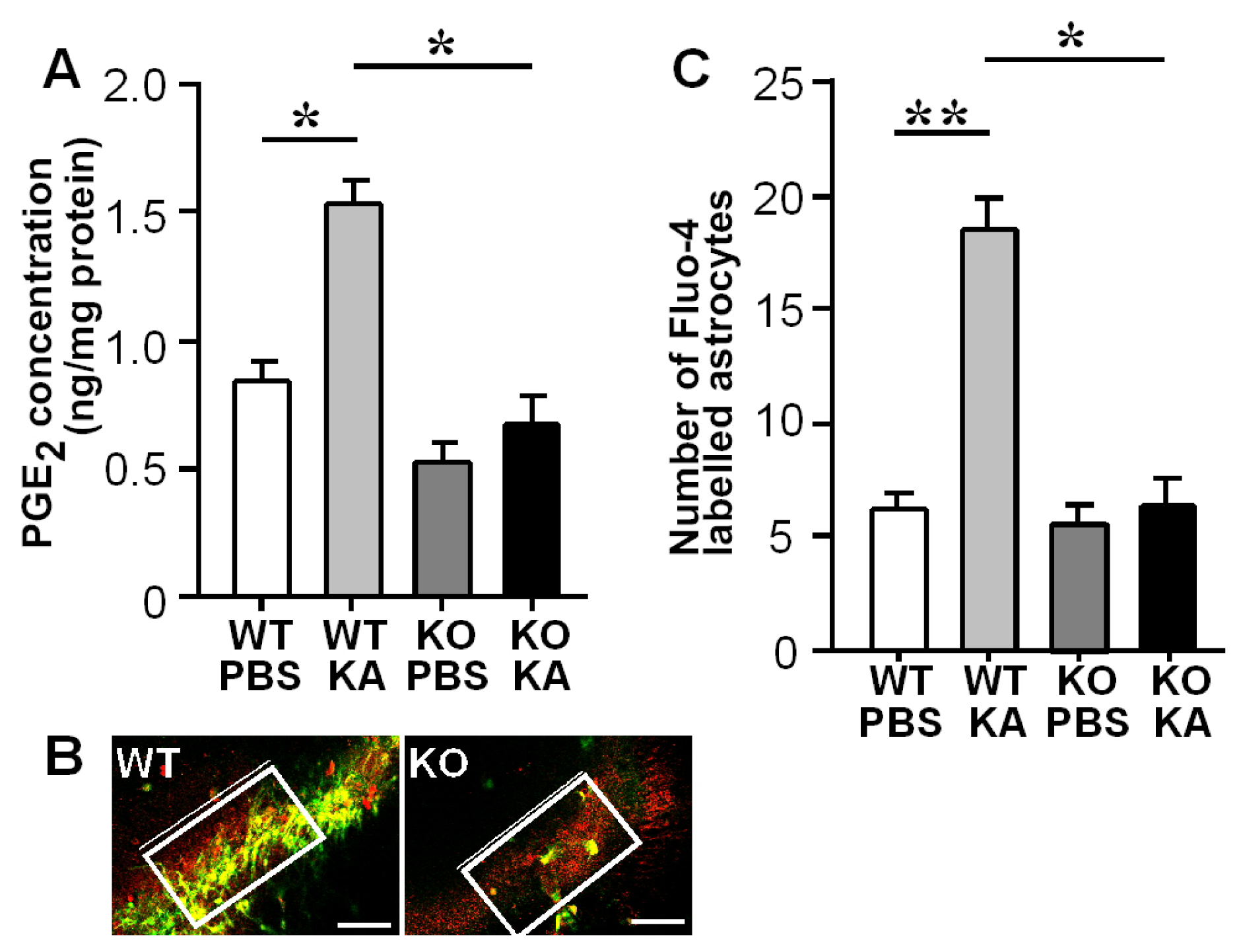

3.2. Increases in Hippocampal PGE2 Concentration and Astrocytic Ca2+ Levels after KA Treatment

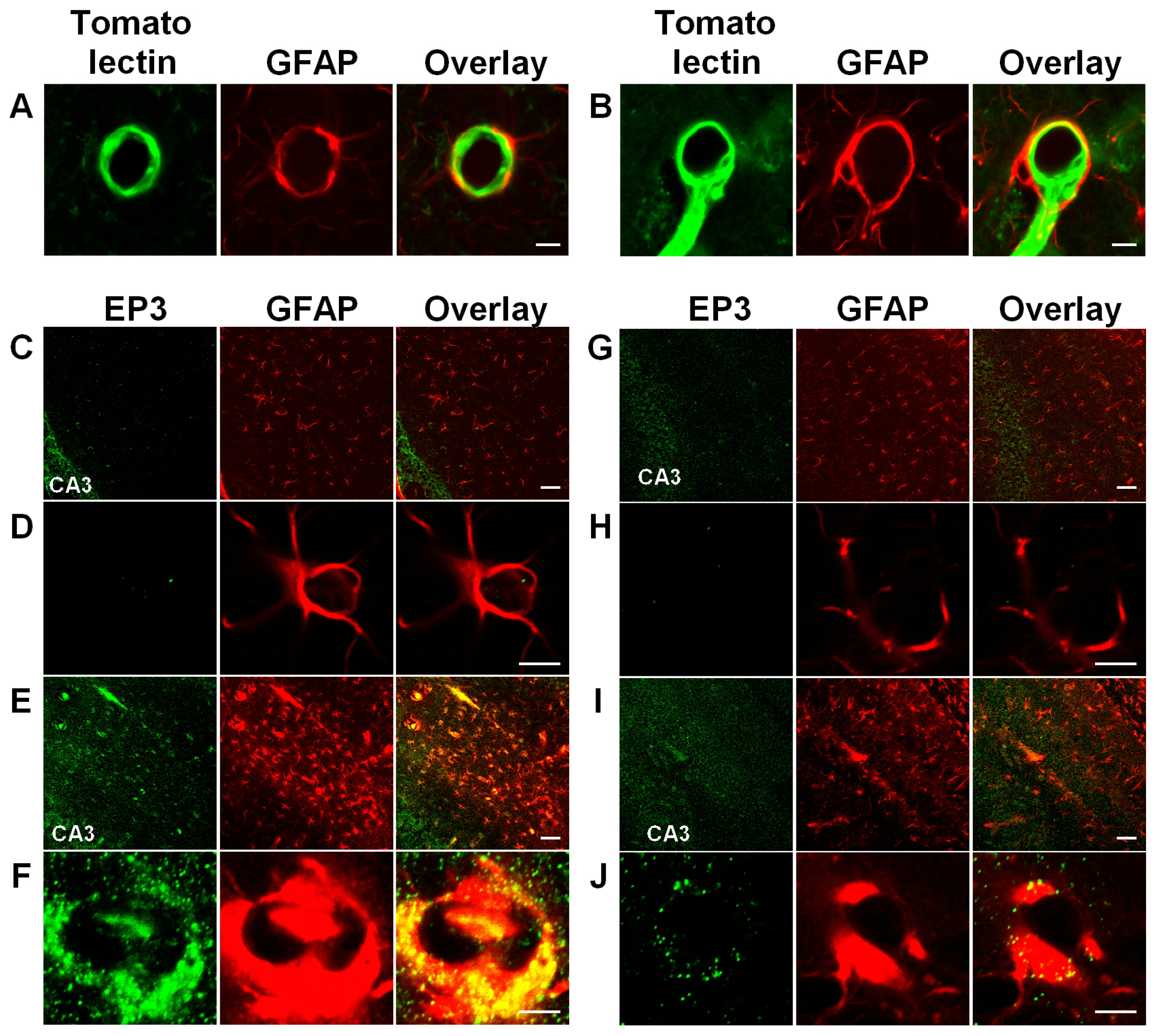

3.3. Activation of Astrocytic EP3 Receptors by KA

3.4. Enhanced Glutamate Release and Neuronal Damage by Endothelial PGE2

3.5. Ca2+-Dependent Glutamate Release

3.6. Intercellular Signaling among Endothelia, Astrocytes and Neurons

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Matsumura, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Onoe, H.; Hayaishi, O. High density of prostaglandin E2 binding sites in the anterior wall of the 3rd ventricle: A possible site of its hyperthermic action. Brain Res 1990, 533, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya, T.; Suzuki, K.; Sugiura, H.; Yasuda, S.; Yamagata, K.; Kawakami, Y.; Maru, E. Inducible brain COX-2 facilitates the recurrence of hippocampal seizures in mouse rapid kindling. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 2003, 71, 205–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T.; Kitagawa, K.; Yamagata, K.; Takemiya, T.; Tanaka, S.; Omura-Matsuoka, E.; Sugiura, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Hori, M. Amelioration of hippocampal neuronal damage after transient forebrain ischemia in cyclooxygenase-2-deficient mice. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 2004, 24, 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Matsumura, K.; Shirakawa, N.; Maeda, M.; Jikihara, I.; Kobayashi, S.; Watanabe, Y. Pyrogenic cytokines injected into the rat cerebral ventricle induce cyclooxygenase-2 in brain endothelial cells and also upregulate their receptors. Eur. J. Neurosci 2001, 13, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Matsumura, K.; Yamagata, K.; Watanabe, Y. Endothelial cells of the rat brain vasculature express cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in response to systemic interleukin-1 beta: A possible site of prostaglandin synthesis responsible for fever. Brain Res 1996, 733, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, C.; Matsumura, K.; Yamagata, K.; Watanabe, Y. Induction by lipopolysaccharide of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in rat brain; its possible role in the febrile response. Brain Res 1995, 697, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, K.; Cao, C.; Ozaki, M.; Morii, H.; Nakadate, K.; Watanabe, Y. Brain endothelial cells express cyclooxygenase-2 during lipopolysaccharide-induced fever: Light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical studies. J. Neurosci 1998, 18, 6279–6289. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata, K.; Andreasson, K.I.; Kaufmann, W.E.; Barnes, C.A.; Worley, P.F. Expression of a mitogen-inducible cyclooxygenase in brain neurons: Regulation by synaptic activity and glucocorticoids. Neuron 1993, 11, 371–386. [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya, T.; Yamagata, K. Chapter 4. Effects of COX-2 Inhibitors on Brain Diseases. In Trends in COX-2 Inhibitor Research; Howardell, M., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 47–75. [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya, T.; Matsumura, K.; Yamagata, K. Roles of prostaglandin synthesis in excitotoxic brain diseases. Neurochem. Int 2007, 51, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya, T.; Yamagata, K. Chapter 3. The Modulatory Role of COX-2 and Prostaglandins in Brain Diseases. In Prostaglandins: New Research; Bronson, C., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 63–89. [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya, T.; Maehara, M.; Matsumura, K.; Yasuda, S.; Sugiura, H.; Yamagata, K. Prostaglandin E2 produced by late induced COX-2 stimulates hippocampal neuron loss after seizure in the CA3 region. Neurosci. Res 2006, 56, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Yamagata, K.; Matsumura, K.; Inoue, W.; Shiraki, T.; Suzuki, K.; Yasuda, S.; Sugiura, H.; Cao, C.; Watanabe, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Coexpression of microsomal-type prostaglandin E synthase with cyclooxygenase-2 in brain endothelial cells of rats during endotoxin-induced fever. J. Neurosci 2001, 21, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar]

- Engblom, D.; Saha, S.; Engstrom, L.; Westman, M.; Audoly, L.P.; Jakobsson, P.J.; Blomqvist, A. Microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 is the central switch during immune-induced pyresis. Nat. Neurosci 2003, 6, 1137–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Trebino, C.E.; Stock, J.L.; Gibbons, C.P.; Naiman, B.M.; Wachtmann, T.S.; Umland, J.P.; Pandher, K.; Lapointe, J.M.; Saha, S.; Roach, M.L.; et al. Impaired inflammatory and pain responses in mice lacking an inducible prostaglandin E synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 9044–9049. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, W.; Matsumura, K.; Yamagata, K.; Takemiya, T.; Shiraki, T.; Kobayashi, S. Brain-specific endothelial induction of prostaglandin E(2) synthesis enzymes and its temporal relation to fever. Neurosci. Res 2002, 44, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ek, M.; Engblom, D.; Saha, S.; Blomqvist, A.; Jakobsson, P.J.; Ericsson-Dahlstrand, A. Inflammatory response: Pathway across the blood-brain barrier. Nature 2001, 410, 430–431. [Google Scholar]

- Cavalheiro, E.A.; Riche, D.A.; Le Gal La Salle, G. Long-term effects of intrahippocampal kainic acid injection in rats: A method for inducing spontaneous recurrent seizures. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol 1982, 53, 581–589. [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya, T.; Matsumura, K.; Sugiura, H.; Maehara, M.; Yasuda, S.; Uematsu, S.; Akira, S.; Yamagata, K. Endothelial microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 exacerbates neuronal loss induced by kainate. J. Neurosci. Res 2010, 88, 381–390. [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S. Lipopolysaccharide-dependent prostaglandin E(2) production is regulated by the glutathione-dependent prostaglandin E(2) synthase gene induced by the Toll-like receptor 4/MyD88/NF-IL6 pathway. J. Immunol 2002, 168, 5811–5816. [Google Scholar]

- Parri, R.; Crunelli, V. An astrocyte bridge from synapse to blood flow. Nat. Neurosci 2003, 6, 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zonta, M.; Angulo, M.C.; Gobbo, S.; Rosengarten, B.; Hossmann, K.A.; Pozzan, T.; Carmignoto, G. Neuron-to-astrocyte signaling is central to the dynamic control of brain microcirculation. Nat. Neurosci 2003, 6, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan, S.J.; MacVicar, B.A. Calcium transients in astrocyte endfeet cause cerebrovascular constrictions. Nature 2004, 431, 195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Turrin, N.P.; Rivest, S. Innate immune reaction in response to seizures: Implications for the neuropathology associated with epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis 2004, 16, 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ciceri, P.; Zhang, Y.; Shaffer, A.F.; Leahy, K.M.; Woerner, M.B.; Smith, W.G.; Seibert, K.; Isakson, P.C. Pharmacology of celecoxib in rat brain after kainate administration. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2002, 302, 846–852. [Google Scholar]

- Janzer, R.C.; Raff, M.C. Astrocytes induce blood-brain barrier properties in endothelial cells. Nature 1987, 325, 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- Bezzi, P.; Carmignoto, G.; Pasti, L.; Vesce, S.; Rossi, D.; Rizzini, B.L.; Pozzan, T.; Volterra, A. Prostaglandins stimulate calcium-dependent glutamate release in astrocytes. Nature 1998, 391, 281–285. [Google Scholar]

- Volterra, A.; Steinhauser, C. Glial modulation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Glia 2004, 47, 249–257. [Google Scholar]

- Haydon, P.G.; Carmignoto, G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol. Rev 2006, 86, 1009–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Perea, G.; Araque, A. Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses. Science 2007, 317, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Fellin, T.; Zhu, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Auberson, Y.P.; Meaney, D.F.; Coulter, D.A.; Carmignoto, G.; Haydon, P.G. Enhanced astrocytic Ca2+ signals contribute to neuronal excitotoxicity after status epilepticus. J. Neurosci 2007, 27, 10674–10684. [Google Scholar]

- Takemiya, T.; Matsumura, K.; Sugiura, H.; Yasuda, S.; Uematsu, S.; Akira, S.; Yamagata, K. Endothelial microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 facilitates neurotoxicity by elevating astrocytic Ca2+ levels. Neurochem. Int 2011, 58, 489–496. [Google Scholar]

- Amano, H.; Hayashi, I.; Endo, H.; Kitasato, H.; Yamashina, S.; Maruyama, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Satoh, K.; Narita, M.; Sugimoto, Y.; et al. Host prostaglandin E(2)-EP3 signaling regulates tumor-associated angiogenesis and tumor growth. J. Exp. Med 2003, 197, 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Kitanaka, J.; Hashimoto, H.; Gotoh, M.; Kondo, K.; Sakata, K.; Hirasawa, Y.; Sawada, M.; Suzumura, A.; Marunouchi, T.; Matsuda, T.; et al. Expression pattern of messenger RNAs for prostanoid receptors in glial cell cultures. Brain Res 1996, 707, 282–287. [Google Scholar]

- Waschbisch, A.; Fiebich, B.L.; Akundi, R.S.; Schmitz, M.L.; Hoozemans, J.J.; Candelario-Jalil, E.; Virtainen, N.; Veerhuis, R.; Slawik, H.; Yrjanheikki, J.; et al. Interleukin-1 beta-induced expression of the prostaglandin E-receptor subtype EP3 in U373 astrocytoma cells depends on protein kinase C and nuclear factor-kappaB. J. Neurochem 2006, 96, 680–693. [Google Scholar]

- Takano, T.; Tian, G.F.; Peng, W.; Lou, N.; Libionka, W.; Han, X.; Nedergaard, M. Astrocyte-mediated control of cerebral blood flow. Nat Neurosci 2006, 9, 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola, C.; Nedergaard, M. Glial regulation of the cerebral microvasculature. Nat. Neurosci 2007, 10, 1369–76. [Google Scholar]

- Fellin, T.; Pascual, O.; Gobbo, S.; Pozzan, T.; Haydon, P.G.; Carmignoto, G. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron 2004, 43, 729–743. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, N.; Xu, J.; Xu, Q.; Nedergaard, M.; Kang, J. Astrocytic glutamate release-induced transient depolarization and epileptiform discharges in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol 2005, 94, 4121–4130. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, G.F.; Azmi, H.; Takano, T.; Xu, Q.; Peng, W.; Lin, J.; Oberheim, N.; Lou, N.; Wang, X.; Zielke, H.R.; et al. An astrocytic basis of epilepsy. Nat. Med 2005, 11, 973–981. [Google Scholar]

- Sanzgiri, R.P.; Araque, A.; Haydon, P.G. Prostaglandin E(2) stimulates glutamate receptor-dependent astrocyte neuromodulation in cultured hippocampal cells. J. Neurobiol 1999, 41, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ortinau, S.; Laube, B.; Zimmermann, H. ATP inhibits NMDA receptors after heterologous expression and in cultured hippocampal neurons and attenuates NMDA-mediated neurotoxicity. J. Neurosci 2003, 23, 4996–5003. [Google Scholar]

- Jeremic, A.; Jeftinija, K.; Stevanovic, J.; Glavaski, A.; Jeftinija, S. ATP stimulates calcium-dependent glutamate release from cultured astrocytes. J. Neurochem 2001, 77, 664–675. [Google Scholar]

- Domercq, M.; Brambilla, L.; Pilati, E.; Marchaland, J.; Volterra, A.; Bezzi, P. P2Y1 receptor-evoked glutamate exocytosis from astrocytes: Control by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and prostaglandins. J. Biol. Chem 2006, 281, 30684–30696. [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani, A.; Sangalli, L.; Wu, H.Q.; Schwarcz, R. ATP as a marker of excitotoxin-induced nerve cell death in vivo. J. Neural. Transm 1987, 70, 349–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, S.; Kikuchi, H.; Ishikawa, M.; Hashimoto, K. Regional changes of tissue pH and ATP content in rat brain following systemic administration of kainic acid. Brain Res 1990, 514, 352–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kambe, Y.; Nakamichi, N.; Georgiev, D.D.; Nakamura, N.; Taniura, H.; Yoneda, Y. Insensitivity to glutamate neurotoxicity mediated by NMDA receptors in association with delayed mitochondrial membrane potential disruption in cultured rat cortical neurons. J. Neurochem 2008, 105, 1886–1900. [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham, G.E.; Fukunaga, Y.; Bading, H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat. Neurosci 2002, 5, 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Vizi, E.S.; Fekete, A.; Karoly, R.; Mike, A. Non-synaptic receptors and transporters involved in brain functions and targets of drug treatment. Br. J. Pharmacol 2010, 160, 785–809. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Takemiya, T.; Yamagata, K. Intercellular Signaling Pathway among Endothelia, Astrocytes and Neurons in Excitatory Neuronal Damage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 8345-8357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14048345

Takemiya T, Yamagata K. Intercellular Signaling Pathway among Endothelia, Astrocytes and Neurons in Excitatory Neuronal Damage. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(4):8345-8357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14048345

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakemiya, Takako, and Kanato Yamagata. 2013. "Intercellular Signaling Pathway among Endothelia, Astrocytes and Neurons in Excitatory Neuronal Damage" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 4: 8345-8357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14048345