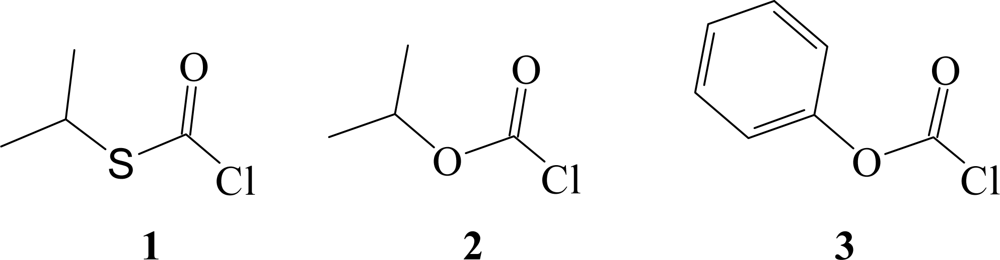

Analysis of the Nucleophilic Solvation Effects in Isopropyl Chlorothioformate Solvolysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

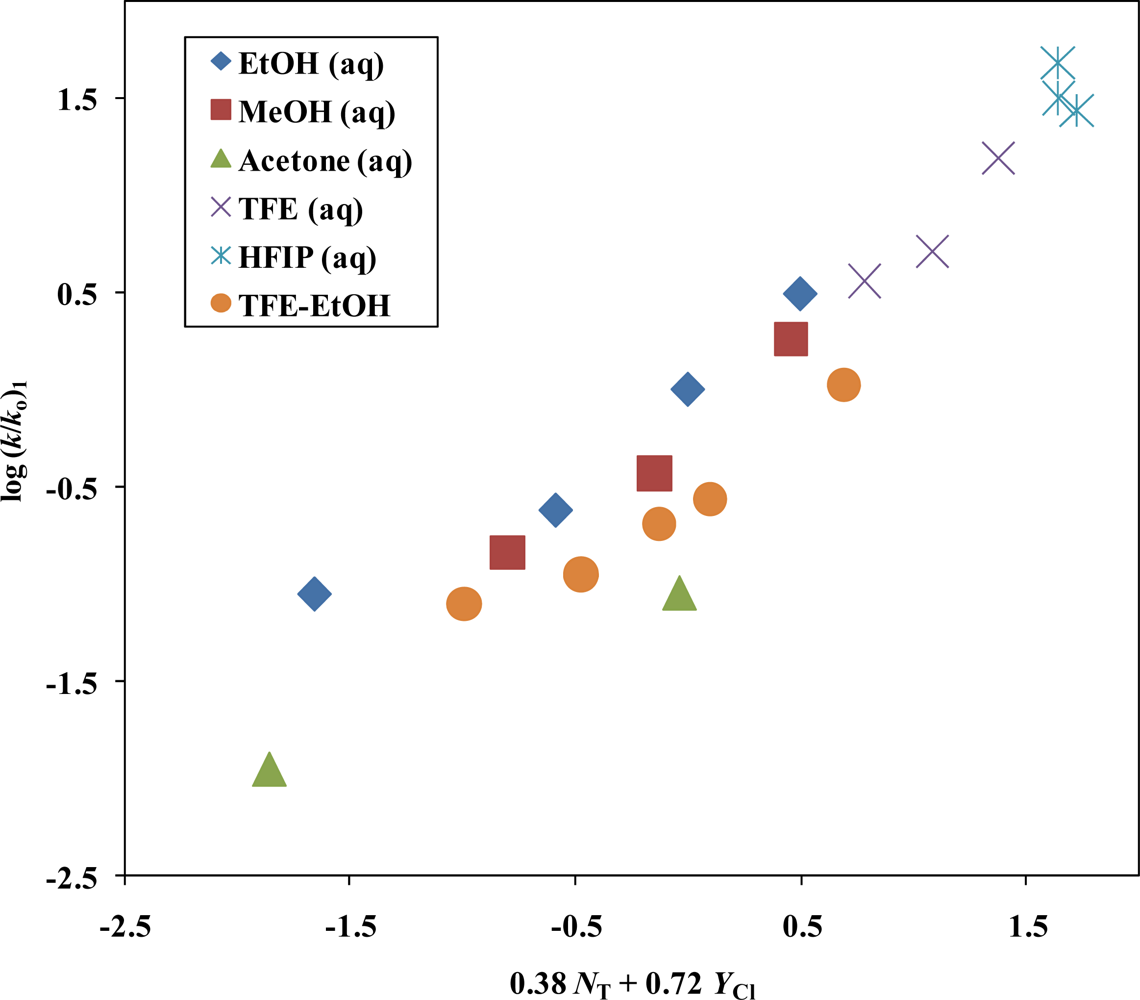

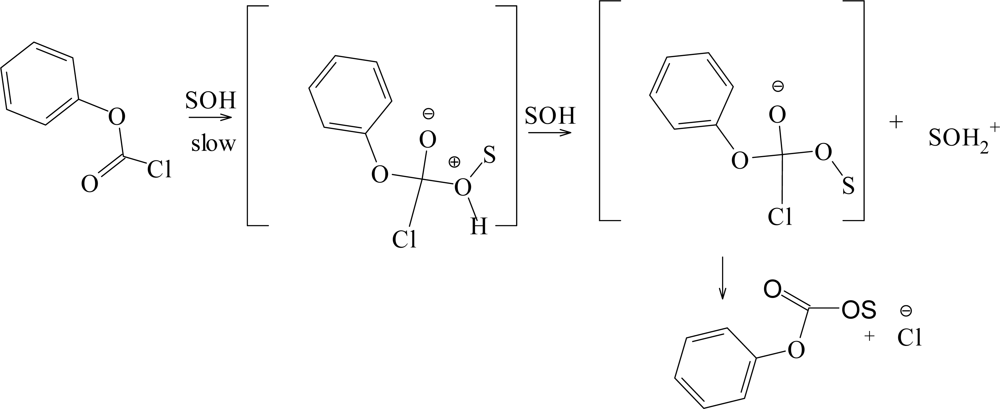

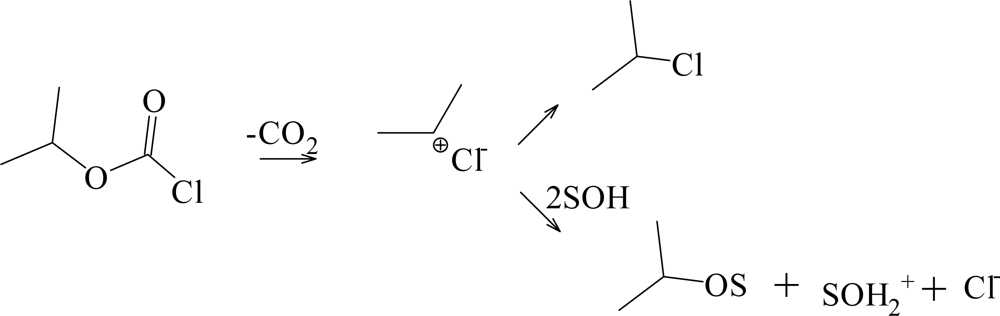

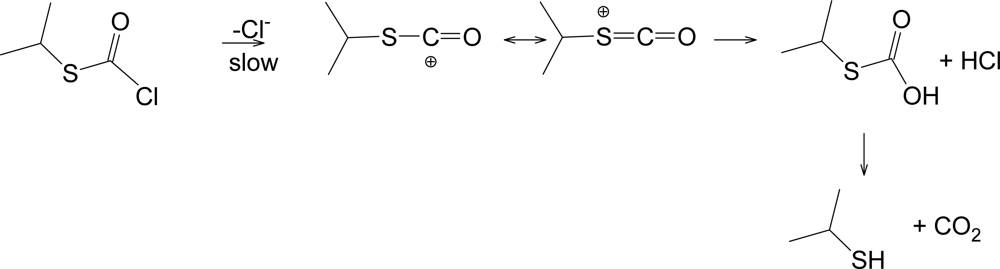

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

4. Experimental Section

Acknowledgments

References and Notes

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Sixty Years of the Grunwald-Winstein Equation: Development and Recent Applications. J Chem Res 2008, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Winstein, S; Grunwald, E; Jones, HW. The Correlation of Solvolyses Rates and the Classification of Solvolysis Reactions into Mechanistic Categories. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1951, 73, 2700–2707. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, E; Winstein, S. The Correlation of Solvolysis Rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1948, 70, 846–854. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Kyong, JB; Weitl, FL. Solvolysis-Decomposition of 1-Adamantyl Chloroformate: Evidence for Ion Pair Return in 1-Adamantyl Chloride Solvolysis. J. Org. Chem 1990, 55, 4304–4311. [Google Scholar]

- Kyong, JB; Suk, YJ; Kevill, DN. Solvolysis-Decomposition of 2-Adamantyl Chloroformate: Evidence for Two Reaction Pathways. J. Org. Chem 2003, 68, 3425–3432. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, IS; Yang, K; Kang, K; Oh, HK; Lee, I. Stoichiometric Solvation Effects. Product-Rate Correlation for the Solvolyses of Phenyl Chloroformate in Alcohol-Water Mixtures. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 1996, 17, 520–524. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Phenyl Chloroformate. J Chem Soc., Perkin Trans 2 1997, 1721–1724. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, IS; Yang, K; Koo, JC; Park, J-K; Lee, I. Stoichiometric Solvation Effects. Part 4. Product–rate Correlations for Solvolyses of p-Methoxyphenyl Chloroformate in Alcohol–Water Mixtures. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 1997, 18, 1017–1021. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, IS; Yang, K; Kang, K; Lee, I; Bentley, TW. Stoichiometric Solvation Effects. Part 3. Product–rate Correlations for Solvolyses of p-Nitrophenyl Chloroformate in Alcohol–Water Mixtures. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans 2 1998, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Concerning the Two Reaction Channels for the Solvolyses of Ethyl Chloroformate and Ethyl Chlorothioformate. J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 2120–2124. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, IS; Yang, K; Kang, K; Lee, I. Transition-State Variation in the Solvolyses of para-Substituted Phenyl Chloroformates in Alcohol-Water Mixtures. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 1998, 19, 968–973. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Kim, JC; Kyong, JB. Correlation of the Rates of Methyl Chloroformate with Solvent Properties. J Chem Res Synop 1999, 150–151. [Google Scholar]

- Kyong, JB; Kim, YG; Kim, DK; Kevill, DN. Dual Pathways in the Solvolyses of Isopropyl Chloroformate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 2000, 21, 662–664. [Google Scholar]

- Park, KH; Kyong, JB; Kevill, DN. Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions of p-Nitrobenzyl Chloroformate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 2000, 21, 1267–1270. [Google Scholar]

- Kyong, JB; Park, B-C; Kim, C-B; Kevill, DN. Rate and Product Studies with Benzyl and p-Nitrobenzyl Chloroformates under Solvolytic Conditions. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 8051–8058. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolyses of n-Octyl Fluoroformate and a Comparison with n-Octyl Chloroformate Solvolyses. J Chem Soc., Perkin Trans 2 2002, 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, EA; Ruiz, MG; Salinas, S; Santos, JG. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Aminolysis of Phenyl and 4-Nitrophenyl Chloroformates in Aqueous Solution. J. Org. Chem 1999, 64, 4817–4820. [Google Scholar]

- Kyong, JB; Won, H; Kevill, DN. Application of the Extended Grunwald-Winstein equation to Solvolyses of n-Propyl Chloroformate. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2005, 6, 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, TW; Harris, HC; Ryu, ZH; Gui, TL; Dae, DS; Szajda, SR. Mechanisms of Solvolyses of Acid Chlorides and Chloroformates. Chloroacetyl and Phenylacetyl Chloride as Similarity Models. J. Org. Chem 2005, 70, 8963–8970. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, ZH; Lee, YH; Oh, Y. Stoichiometric Effects. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Isopropenyl Chloroformate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 2005, 26, 1761–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Koyoshi, F; D’Souza, MJ. Correlation of the Specific Rates of Solvolysis of Aromatic Carbamoyl Chlorides, Chloroformates, Chlorothionoformates, and Chlorodithioformates Revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2007, 8, 346–352. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, MJ; Reed, D; Koyoshi, F; Kevill, DN. Consideration of the Factors Influencing the Specific Rates of Solvolysis of p-Methoxyphenyl Chloroformate. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2007, 8, 788–796. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, MJ; Shuman, KE; Carter, SE; Kevill, DN. Extended Grunwald-Winstein Analysis–LFER Used to Gauge Solvent Effects in p-Nitrophenyl Chloroformate Solvolysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2008, 9, 2231–2242. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, MJ; Reed, DN; Erdman, KJ; Kevill, DN. Grunwald-Winstein Analysis–Isopropyl Chloroformate Solvolysis Revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2009, 10, 862–879. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Phenyl Chlorothionoformate and Phenyl Chlorodithioformate. Can. J. Chem 1999, 77, 1118–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Dual Pathways in the Solvolyses of Phenyl Chlorothioformate. J. Org. Chem 1997, 62, 7869–7871. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, IS; Yang, K; Kang, DH; Park, HJ; Kang, K; Lee, I. Transition-State Variation in the Solvolyses of Phenyl Chlorothionoformate in Alcohol-Water Mixtures. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 1999, 20, 577–580. [Google Scholar]

- An, SK; Yang, JS; Cho, JM; Yang, K; Lee, PL; Bentley, TW; Lee, I; Koo, IS. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Phenyl Chlorodithioformate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc 2002, 23, 1445–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, TW. Structural Effects on the Solvolytic Reactivity of Carboxylic and Sulfonic Acid Chlorides. Comparisons with Gas-Phase Data for Cation Formation. J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 6251–6257. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, MJ; Hailey, SM; Kevill, DN. Use of Empirical Correlations to Determine Solvent Effects in the Solvolysis of S-Methyl Chlorothioformate. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2010, 11, 2253–2266. [Google Scholar]

- Polshettiwar, V; Kaushik, MP. Recent Advances in Thionating Agents for the Synthesis of Organosulfur Compounds. J. Sulf. Chem 2006, 27, 353–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori, S; Yoshida, Y; Tsuchidate, T; Ishii, Y. Studies on Sulfur Containing Carbonates and Their Pesticidal Activities. Agr. Biol. Chem 1969, 33, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Petit-Dominguez, MD; Martinez-Maganto, J. MCF Fast Derivatization Procedure for the Identification of Resinous Deposit Components from the Inner Walls of Roman Age Amphorae by GC-MS. Talanta 2000, 51, 727–734. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, TW; Llewellyn, G. Yx Scales of Solvent Ionizing Power. Prog. Phys. Org. Chem 1990, 17, 121–158. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Additional YCl Values and Correlation of the Specific Rates of Solvolysis of tert-Butyl Chloride in Terms of NT and YCl Scales. J Chem Res Synop 1993, 174–175. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Ryu, ZH. Additional Solvent Ionizing Power Values for Binary Water-1,1,1,3,3,3,Hexafluoro-2-propanol Solvents. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2006, 7, 451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Anderson, SW. An Improved Scale of Solvent Nucleophilicity Based on the Solvolysis of the S-Methyldibenzothiophenium Ion. J. Org. Chem 1991, 56, 1845–1850. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN. Development and Uses of Scales of Solvent Nucleophilicity. In Advances in Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships; Charton, M, Ed.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, TW; Koo, IS; Norman, SJ. Distinguishing Between Solvation Effects and Mechanistic Changes. Effects Due to Differences in Solvation of Aromatic Rings and Alkyl Groups. J. Org. Chem 1991, 56, 1604–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, KT; Sheu, HC. Solvolysis of 2-Aryl-2-Chloroadamantanes. A New Y scale for Benzylic Chlorides. J. Org. Chem 1991, 56, 3021–3025. [Google Scholar]

- Fujio, M; Saeki, Y; Nakamoto, K; Yatsugi, K; Goto, N; Kim, SH; Tsuji, Y; Rappoport, Z; Tsuno, Y. Solvent Effects on Anchimerically Assisted Solvolyses. II. Solvent Effects in Solvolyses of threo-2-Aryl-1-methylpropyl-p-toluenesulfonates. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1995, 68, 2603–2617. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Ismail, NHJ; D’Souza, MJ. Solvolysis of the (p-Methoxybenzyl)dimethylsulfonium Ion. Development and Use of a Scale to Correct for Dispersion in Grunwald-Winstein Plots. J. Org. Chem 1994, 59, 6303–6312. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, MJ; Darrington, AM; Kevill, DN. On the Importance of the Aromatic Ring Parameter in Studies of the Solvolyses of Cinnamyl and Cinnamoyl Halides. Org. Chem. Int 2010, 2, 13050621–13050629. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, DS; Jayakumar, KP; Balachandran, S. The Leaving Group Dependence in the Rates of Solvolysis of 1,2-Phenylethyl System. J Phys Org Chem 2010. doi:10.1002/poc.1662.. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; D’Souza, MJ. Use of the Simple and Extended Grunwald-Winstein Equations in the Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Highly Hindered Tertiary Alkyl Derivatives. Cur. Org. Chem 2010, 14, 1037–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I. Nucleophilic Substitution at a Carbonyl Carbon. Part II. CNDO/2 Studies on Conformation and Reactivity of the Thio-Analogues of Methyl Chloroformate. J. Korean Chem. Soc 1972, 16, 334–340. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN. Chloroformate Esters and Related Compounds. In The Chemistry of the Functional Groups: The Chemistry of Acyl Halides; Patai, S, Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ; Chapter 12, pp. 381–453. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, CJ; True, NS; Bohn, RK. Low Resolution Microwave Spectroscopy. 13. Conformations of S-n-Propyl Thioesters. J. Phys. Chem 1978, 82, 483–488. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Q; Krisak, R; Hagen, K. The Molecular Structure of Methyl Chlorothioformate by Gas-Phase Electron Diffraction and Microwave Spectroscopy Data. J. Mol. Struc 1995, 346, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gobbato, KI; Della Védova, CO; Mack, H-G; Oberhammer, H. Structures and Conformations of (Trifluoromethyl)thioacetic Acid, CF3C(O)SH, and Derivatives CF3C(O)SCH3 and CF3C(O)SCl. Inorg. Chem 1996, 35, 6152–6157. [Google Scholar]

- So, SP. Structures, Relative Stabilities and Barriers to Internal Rotation of Chloroformyl Hypochlorite and Thiohypochlorite. J Mol Struc Theochem 1998, 168, 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Ulic, SE; Coyanis, EM; Romano, RM; Della Védova, CO. S-Ethyl Thiochloroformate, ClC(O)CH2CH3: Unusual Conformational Properties? Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spec 1998, 54, 695–705. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, RM; Della Védova, CO; Downs, AJ; Parsons, S; Smith, S. Structural and Vibrational Properties of ClC(O)SY Compounds with Y = Cl and CH3. New J. Chem 2003, 27, 514–519. [Google Scholar]

- Erben, MF; Della Védova, CO; Boese, R; Willner, H; Oberhammer, H. Trifluoromethyl Chloroformate: ClC(O)OCF3: Structure, Conformation, and Vibrational Analysis Studied by Experimental and Theoretical Methods. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 699–706. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, CJ; True, NS; Bohn, RK. Low Resolution Microwave Spectroscopy: Part 14. Conformations of S-isopropyl Thioesters and a High Resolution Study of S-isopropyl Thiofluoroformate. J. Mol. Struct 1979, 51, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Bond, MW; D’Souza, MJ. Dual Pathways in the Solvolyses of Phenyl Chlorothioformate. J. Org. Chem 1997, 62, 7869–7871. [Google Scholar]

- Crunden, EW; Hudson, RF. The Mechanism of Hydrolysis of Acid Chlorides. Part VII. Alkyl Chloroformates. J Chem Soc 1961, 3748–3755. [Google Scholar]

- Queen, A. Kinetics of the Hydrolysis of Acyl Chlorides in Pure Water. Can. J. Chem 1967, 45, 1619–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Queen, A; Nour, TA; Paddon-Row, MN; Preston, K. Kinetics and Hydrolysis of Thiochloroformate Esters in Pure Water. Can. J. Chem 1970, 48, 522–527. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, DM; Queen, A. Kinetics and Mechanism for the Hydrolysis of Chlorothionoformate and Chlorodithioformate Esters in Water and Aqueous Acetone. Can. J. Chem 1972, 50, 1401–1406. [Google Scholar]

- La, S; Koh, KS; Lee, I. Nucleophilic Substitution at a Carbonyl Carbon Atom (XI). Solvolysis of Methyl Chloroformate and Its Thioanalogues in Methanol, Ethanol and Ethanol-Water Mixtures. J. Korean Chem. Soc 1980, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- La, S; Koh, KS; Lee, I. Nucleophilic Substitution at a Carbonyl Carbon Atom (XII). Solvolysis of Methyl Chloroformate and Its Thioanalogues in CH3CN-H2O and CH3COCH3-H2O Mixtures. J. Korean Chem. Soc 1980, 24, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, EA. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Reactions of Thiol, Thiono, and Dithio Analogues of Carboxylic Esters with Nucleophilies. Chem. Rev 1999, 99, 3505–3524. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, EA; Cubillos, M; Santos, JG. Kinetics and Mechanisms of the Pyridinolysis of Phenyl and 4-Nitrophenyl Chlorothionoformates. Formation and Hydrolysis of 1-(Aryloxythiocarbonyl)pyridinum Cations. J. Org. Chem 2004, 69, 4802–4807. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, EA; Aliaga, M; Gazitúa, M; Santos, JG. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Reactions of S-Methyl Chlorothioformate with Pyridines and Secondary Alicyclic Amines. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 4863–4869. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, EA. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Reactions of Thiol, Thiono, and Dithio Analogues of Carboxylic Esters with Nucleophilies. An Update. J. Sulf. Chem 2007, 28, 401–429. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, EA; Aliaga, M; Campodonico, PR; Leis, JR; García-Río, L; Santos, JG. Reactions of Aryl Chlorothionoformates with Quinuclidines. A Kinetic Study. J. Phys. Org. Chem 2008, 21, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, EA; Gazitúa, M; Santos, JG. Kinetics and Mechanism of the Reactions of Aryl Chlorodithioformates with Pyridines and Secondary Alicyclic Amines. J. Phys. Org. Chem 2009, 22, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza, MJ; Ryu, ZH; Park, B-C; Kevill, DN. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Acetyl Chloride and α-Substituted Derivatives. Can. J. Chem 2008, 86, 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, AA; Pearson, RG. Kinetics and Mechanism-a Study of Homogeneous Chemical Reactions, 2nd ed; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1961; pp. 49–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, DN; Abduljaber, MH. Correlation of the Rates of Solvolysis of Cyclopropylcarbinyl and Cyclobutyl Bromides Using the Extended Grunwald-Winstein Equation. J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 2548–2554. [Google Scholar]

| Solvent (%)a | 1 @ 25.0 °C; 105k, s−1b | NTc | YCld | k1/k2e | Etf | Phg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% MeOH | 1.99 ± 0.11h | 0.17 | −1.2 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.042 |

| 90% MeOH | 5.06 ± 0.24 | −0.01 | −0.20 | 0.61 | ||

| 80% MeOH | 24.7 ± 0.3 | −0.06 | 0.67 | 1.84 | 0.40 | |

| 100% EtOH | 1.21 ± 0.06i | 0.37 | −2.50 | 1.11 | 0.19 | 0.026 |

| 90% EtOH | 3.32 ± 0.17 | 0.16 | −0.90 | 1.41 | 0.21 | 0.029 |

| 80% EtOH | 13.7 ± 0.7j | 0.00 | 0.00 | 3.49 | 0.37 | 0.029 |

| 70% EtOH | 42.1 ± 1.3 | −0.20 | 0.80 | 7.61 | 0.029 | |

| 90% Acetone | 0.153 ± 0.004k | −0.35 | −2.39 | 0.46 | ||

| 70% Acetone | 1.21 ± 0.06 | −0.42 | 0.17 | 0.47 | ||

| 97% TFE (w/w) | 49.8 ± 2.5l | −3.30 | 2.83 | 4.05 | 260 | 5.9 |

| 90% TFE (w/w) | 69.5 ± 2.1 | −2.55 | 2.85 | 5.00 | 171 | 0.50 |

| 70% TFE (w/w) | 212 ± 18m | −1.98 | 2.96 | 10.76 | 89 | |

| 80T-20E | 14.5 ± 0.8 | −1.76 | 1.89 | 4.45 | 0.10 | |

| 60T-40E | 3.75 ± 0.18 | −0.94 | 0.63 | 2.66 | 0.033 | |

| 50T-50E | 2.81 ± 0.02 | −0.64 | 0.60 | |||

| 40T-60E | 1.55 ± 0.16 | −0.34 | −0.48 | 1.61 | ||

| 20T-80E | 1.09 ± 0.13 | 0.08 | −1.42 | 1.44 | ||

| 97%HFIP (w/w) | 376 ± 17 | −5.26 | 5.17 | 2.58 | 253 | |

| 90%HFIP (w/w) | 437 ± 28n | −3.84 | 4.41 | 6.91 | 357 | 16 |

| 70%HFIP (w/w) | 659 ± 39o | −2.94 | 3.83 | 10.97 | 183 | 0.22p |

| Substrate | na | lb | mb | cc | Rd | Fe | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhOCOClf | 49 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.980 | 568 | A-E |

| PhSCSClg | 31 | 0.69 ± 0.05 | 0.95 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.05 | 0.987 | 521 | SN1 |

| PhOCSClh | 9 | 1.88 ± 0.28 | 0.56 ± 0.15 | 0.38 ± 0.15 | 0.950 | 28 | A-E |

| 18 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.09 | −2.54 ± 0.34 | 0.955 | 77 | SN1 | |

| PhSCOCli | 16 | 1.74 ± 0.17 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | 0.19 ± 0.23 | 0.946 | 55 | A-E |

| 6 | 0.62 ± 0.08 | 0.92 ± 0.11 | −2.29 ± 0.13 | 0.983 | 44 | SN1 | |

| EtOCOClj | 28 | 1.56 ± 0.09 | 0.55 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.24 | 0.967 | 179 | A-E |

| 7 | 0.69 ± 0.13 | 0.82 ± 0.16 | −2.40 ± 0.27 | 0.946 | 17 | SN1 | |

| EtSCOClk | 19 | 0.66 ± 0.08 | 0.93 ± 0.07 | −0.16 ± 0.31 | 0.961 | 96 | SN1 |

| MeOCOCll | 19 | 1.59 ± 0.09 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.07 | 0.977 | A-E | |

| MeSCOClm | 12 | 1.48 ± 0.18 | 0.44 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.08 | 0.949 | 40 | A-E |

| 8 | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | −0.27 ± 0.18 | 0.987 | 95 | SN1 | |

| i-PrOCOCln | 9 | 1.35 ± 0.22 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.960 | 35 | A-E |

| 16 | 0.28 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.04 | −0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.982 | 176 | fragmentation-ionization | |

| i-PrSCOClo | 19 | 0.38 ± 0.11 | 0.72 ± 0.09 | −0.28 ± 0.10 | 0.961 | 97 | SN1 |

© 2010 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Souza, M.J.; Mahon, B.P.; Kevill, D.N. Analysis of the Nucleophilic Solvation Effects in Isopropyl Chlorothioformate Solvolysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 2597-2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11072597

D’Souza MJ, Mahon BP, Kevill DN. Analysis of the Nucleophilic Solvation Effects in Isopropyl Chlorothioformate Solvolysis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2010; 11(7):2597-2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11072597

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Souza, Malcolm J., Brian P. Mahon, and Dennis N. Kevill. 2010. "Analysis of the Nucleophilic Solvation Effects in Isopropyl Chlorothioformate Solvolysis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 11, no. 7: 2597-2611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms11072597