Antimalarials with Benzothiophene Moieties as Aminoquinoline Partners

Abstract

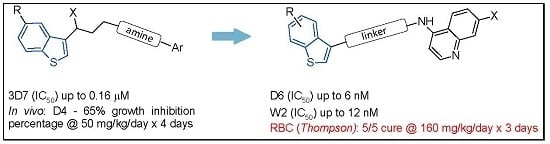

:1. Introduction

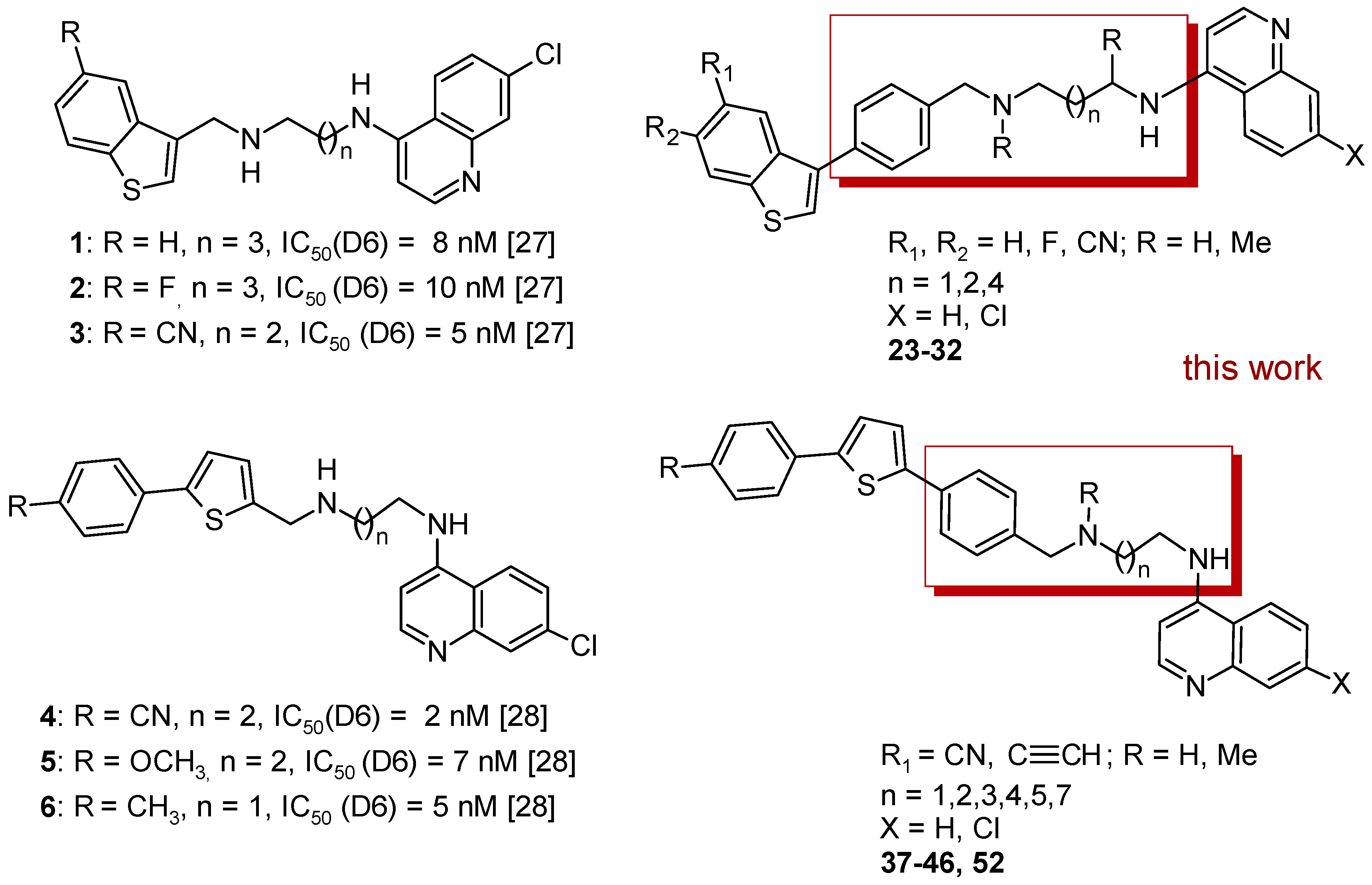

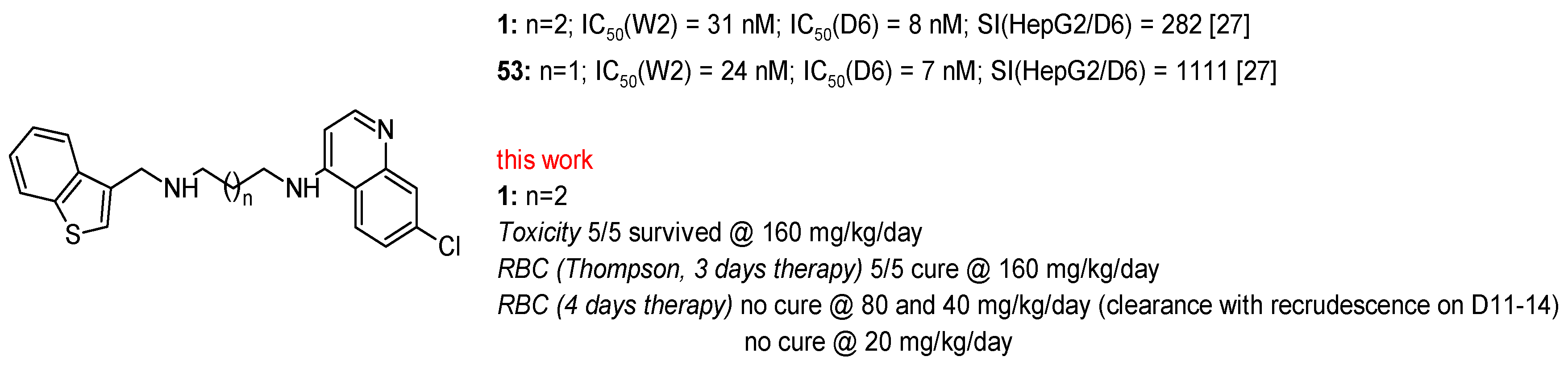

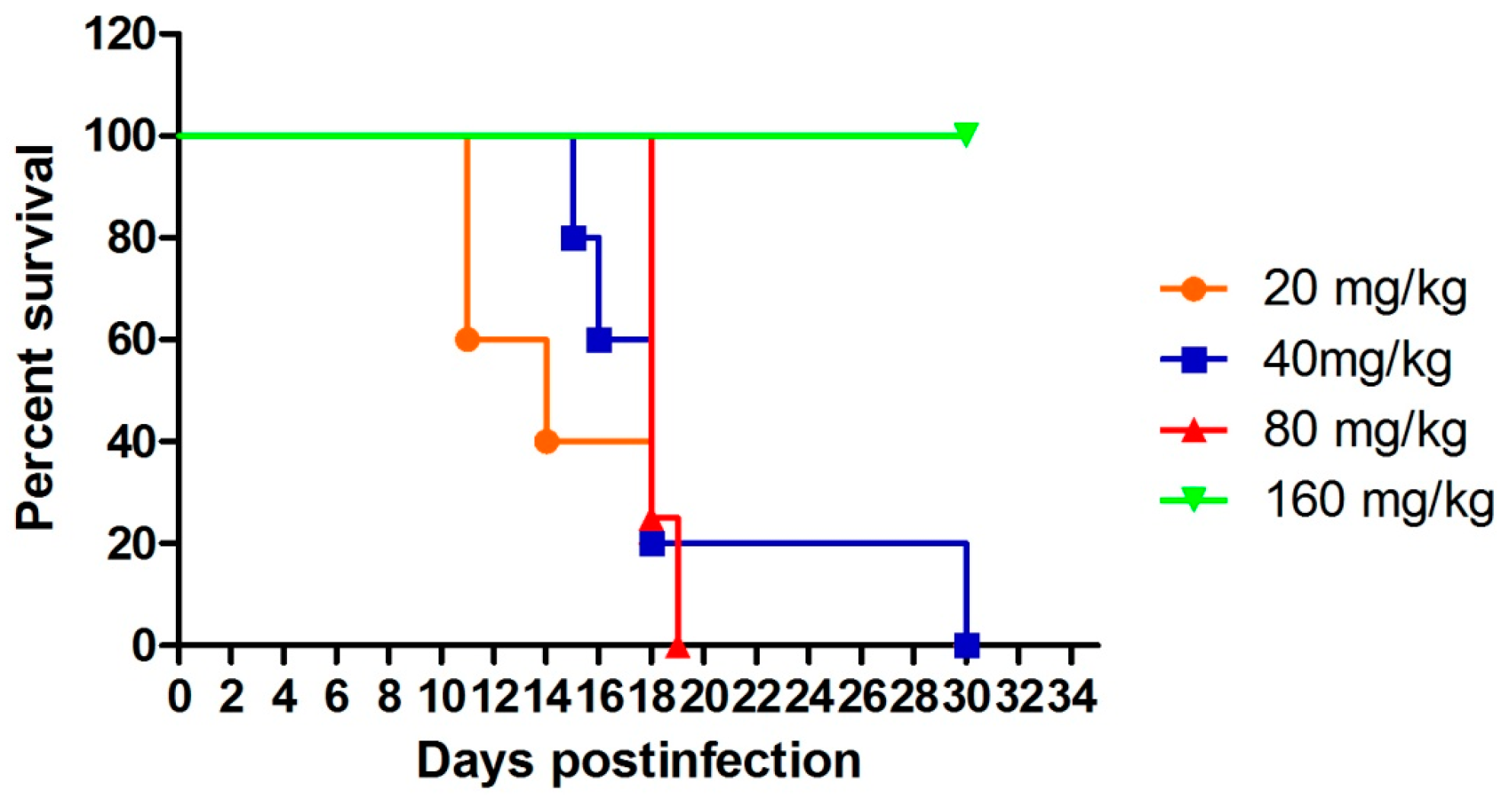

2. Results

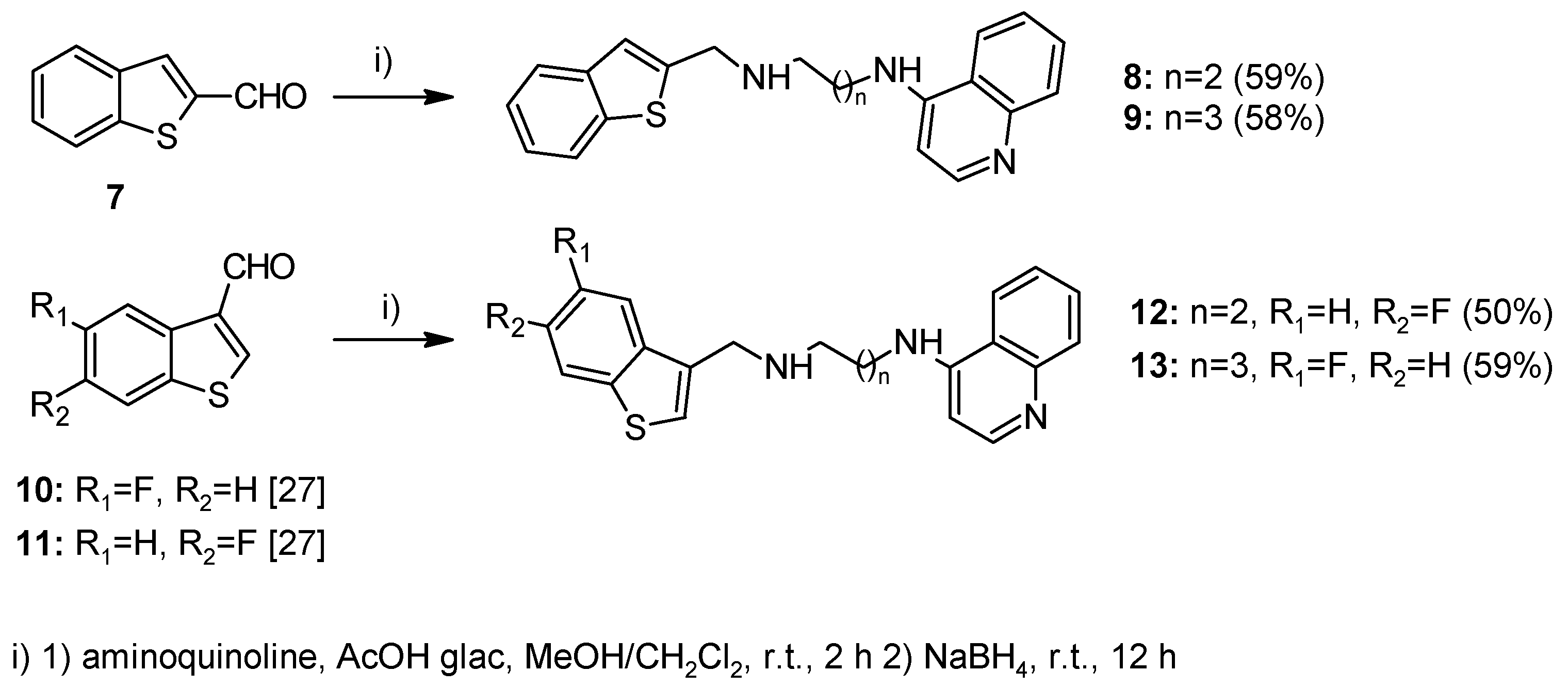

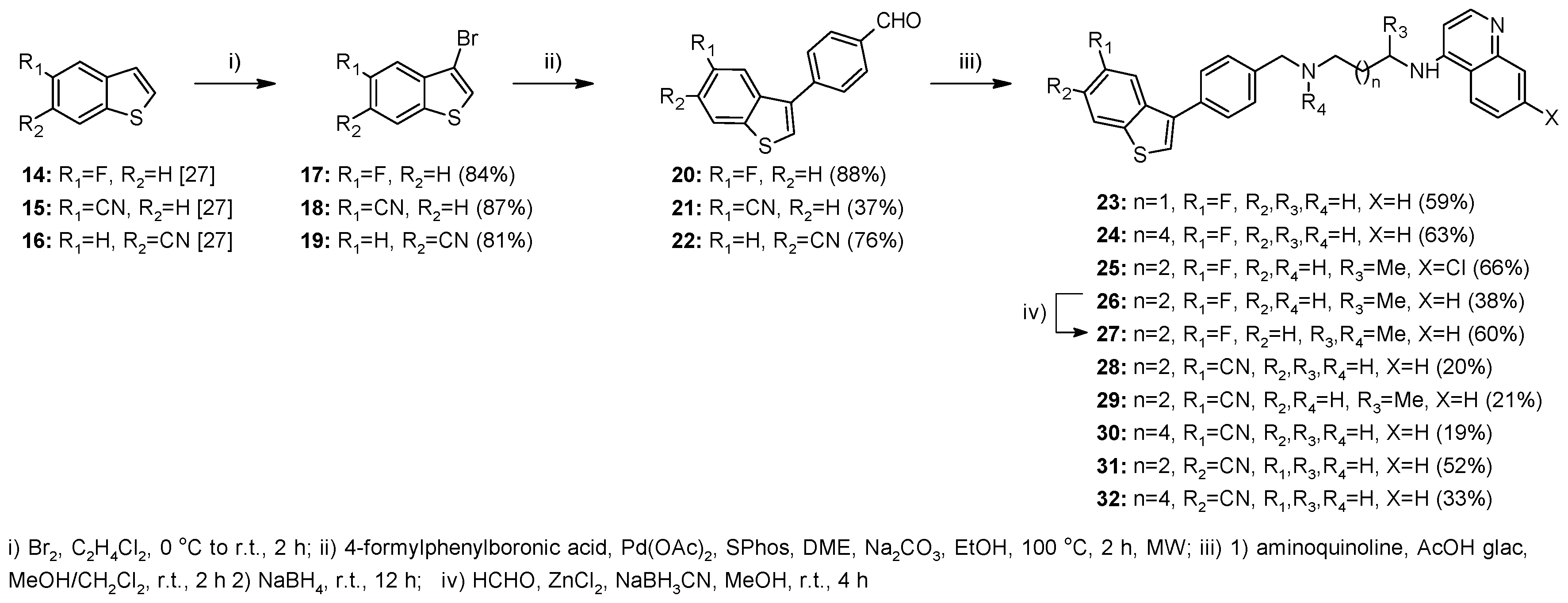

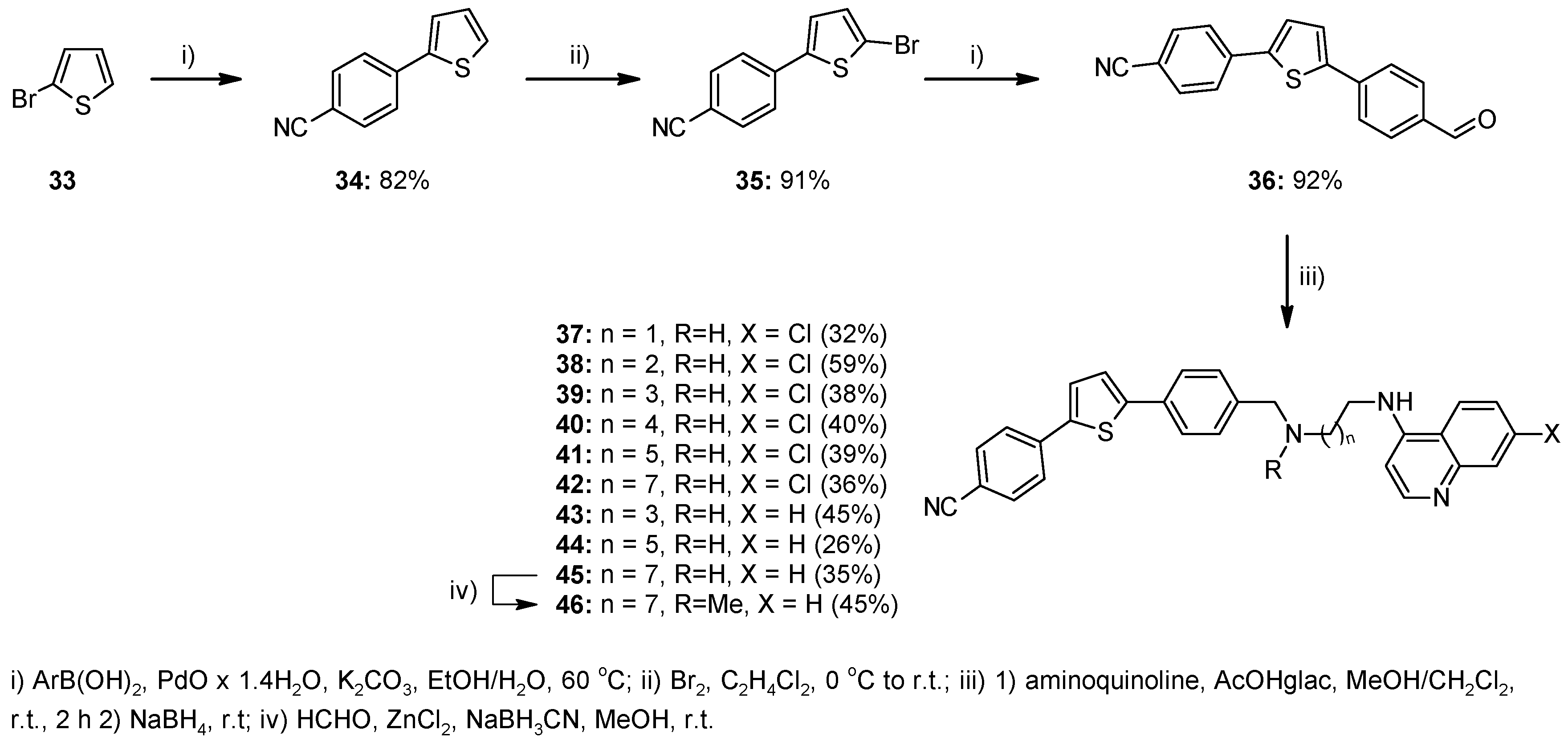

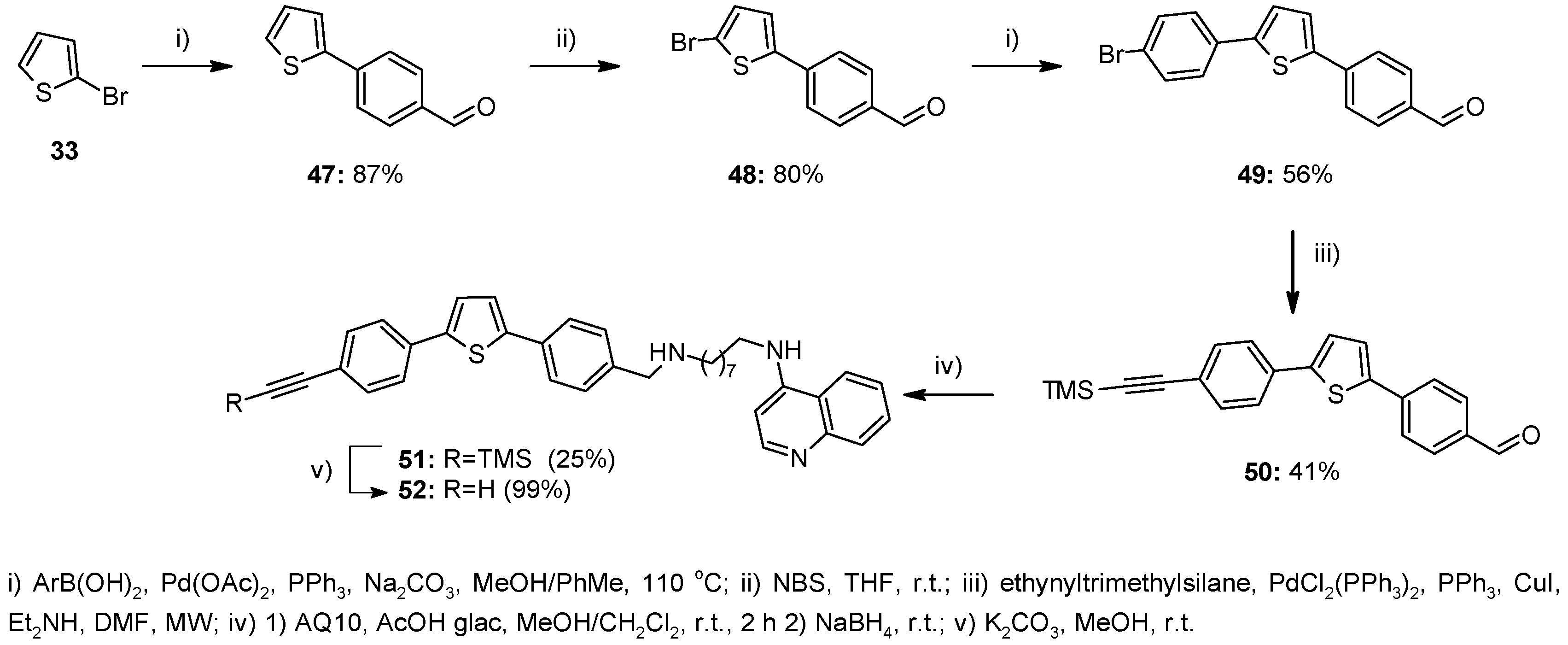

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. In Vitro Antiplasmodial Activity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemistry

4.1.1. General Experimental Procedures

4.1.2. Method A—General Procedure for Reductive Amination for Compounds 8, 9, 12, 13, 23–26, 28–32, 37–45, 51

4.1.3. Method B—General Experimental Procedure for Bromination for Compounds 17–19, 35

4.1.4. Method C—General Procedure for Suzuki Coupling for Compounds 20–22

4.1.5. Method D—General Procedure for Synthesis of Aminoquinolines AQ88, AQ9 and AQ10

4.1.6. Method E—General Procedure for N-Methylation of Aminoquinolines for Compounds 27 and 46

4.1.7. Method F—General Procedure for the Suzuki Coupling Reaction Using PdO × 1.4 H2O for Compounds 34, 36

4.1.8. Method G—General Procedure for the Suzuki Coupling in MeOH/Toluene for Compounds 47, 49

4.2. In Vitro Antiplasmodial Activity

4.3. In Vivo Antiplasmodial Activity and Toxicity

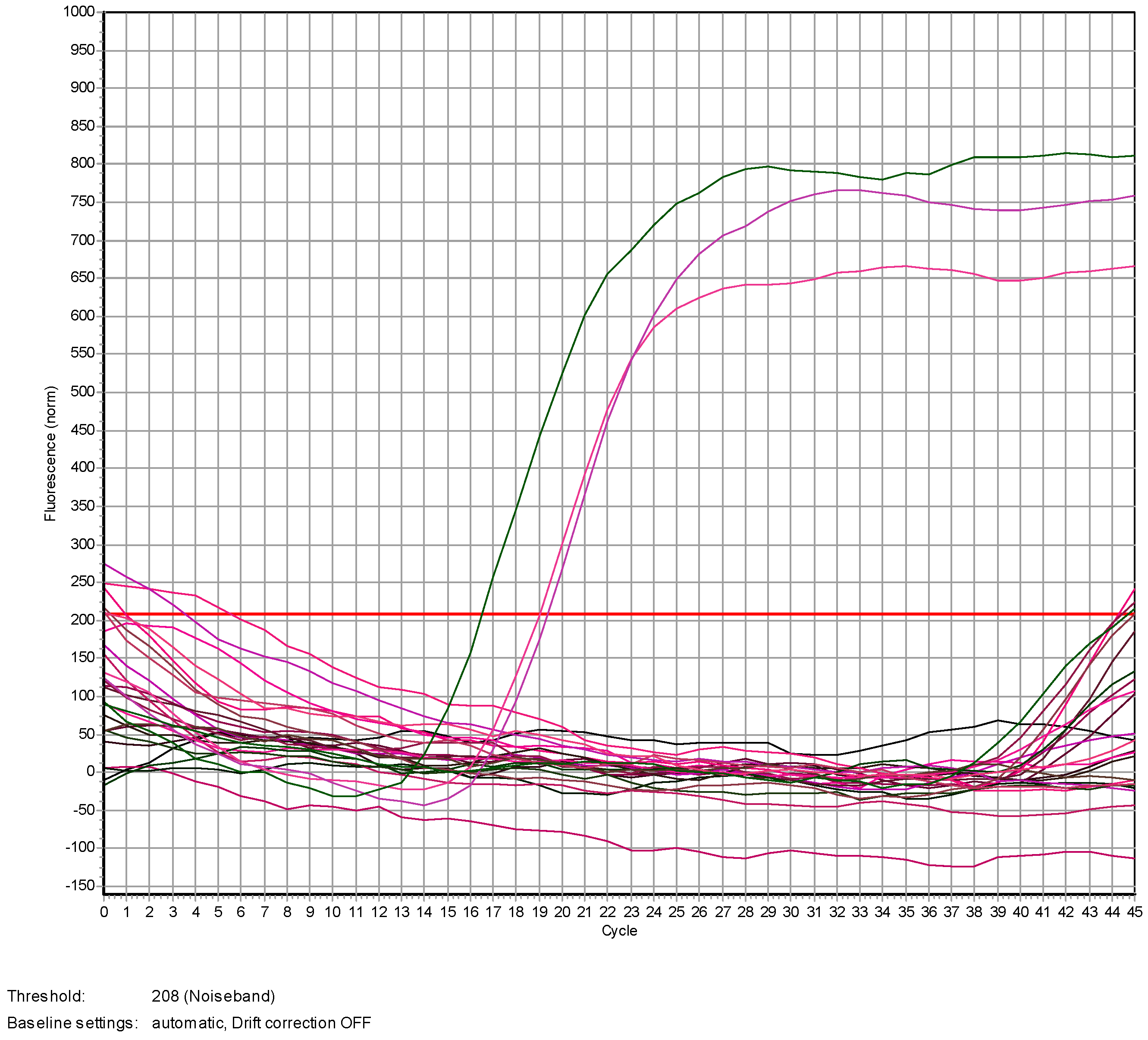

4.4. Genomic DNA Extraction and qPCR Analysis

4.4.1. DNA Extraction

4.4.2. Real Time PCR

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soulard, V.; Bosson-Vanga, H.; Lorthiois, A.; Roucher, C.; Franetich, J.; Zanghi, G.; Bordessoulles, M.; Tefit, M.; Thellier, M.; Morosan, S.; et al. Plasmodium falciparum full life cycle and Plasmodium ovale liver stages in humanized mice. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Malaria Report, 2015. Available online: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world-malaria-report-2015/report/en/ (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- Ashley, E.A.; Dhorda, M.; Fairhurst, R.M.; Amaratunga, C.; Lim, P.; Suon, S.; Sreng, S.; Anderson, J.M.; Mao, S.; Sam, B.; et al. Spread of Artemisinin Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum Malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Overview of Malaria Treatment. Available online: http://www.who.int/malaria/areas/treatment/overview/en/ (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- Dholakia, N.; Dhandhukia, P.; Roy, N. Screening of potential targets in Plasmodium falciparum using stage-specific metabolic network analysis. Mol. Divers. 2015, 19, 991–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, I.M.; Bray, P.G.; Ward, S.A. Parasitology. A requiem for chloroquine. Science 2002, 298, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidock, D.A.; Nomura, T.; Talley, A.K.; Cooper, R.A.; Dzekunov, S.M.; Ferdig, M.T.; Ursos, L.M. B.; Sidhu, A.B.S.; Naude, B.; Deitsch, K.W.; et al. Mutations in the P. falciparum Digestive Vacuole Transmembrane Protein PfCRT and Evidence for Their Role in Chloroquine Resistance. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, T.; Sharma, S.K.; Kapoor, N.; Dwivedi, V.; Surolia, N.; Surolia, A. Benzothiophene carboxamide derivatives as inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum enoyl-ACP reductase. IUBMB Life 2011, 63, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhibber, M.; Kumar, G.; Parasuraman, P.; Ramya, T.N.C.; Surolia, N.; Surolia, A. Novel diphenyl ethers: Design, docking studies, synthesis and inhibition of enoyl ACP reductase of Plasmodium falciparum and Escherichia coli. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 8086–8098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.K.; Parasuraman, P.; Kumar, G.; Surolia, N.; Surolia, A. Green Tea Catechins Potentiate Triclosan Binding to Enoyl-ACP Reductase from Plasmodium falciparum (PfENR). J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carballeira, N.M.; Bwalya, A.G.; Itoe, M.A.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Cordero-Maldonado, M.L.; Kaiser, M.; Mota, M.M.; Crawford, A.D.; Guido, R.V.C.; Tasdemir, D. 2-Octadecynoic acid as a dual life stage inhibitor of Plasmodium infections and plasmodial FAS-II enzymes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 4151–4157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rackham, M.D.; Brannigan, J.A.; Moss, D.K.; Yu, Z.; Wilkinson, A.J.; Holder, A.A.; Tate, E.W.; Leatherbarrow, R.J. Discovery of Novel and Ligand-Efficient Inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax N-Myristoyltransferase. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rackham, M.D.; Brannigan, J.A.; Rangachari, K.; Meister, S.; Wilkinson, A.J.; Holder, A.A.; Leatherbarrow, R.J.; Tate, E.W. Design and Synthesis of High Affinity Inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax N-Myristoyltransferases Directed by Ligand Efficiency Dependent Lipophilicity (LELP). J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2773–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavic, K.; Krishna, S.; Derbyshire, E.T.; Staines, H.M. Plasmodial sugar transporters as anti-malarial drug targets and comparisons with other protozoa. Malar. J. 2011, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavic, K.; Derbyshire, E.T.; Naftalin, R.J.; Krishna, S.; Staines, H.M. Comparison of effects of green tea catechins on apicomplexan hexose transporters and mammalian orthologues. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2009, 168, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saliba, K.J.; Krishna, S.; Kirk, K. Inhibition of hexose transport and abrogation of pH homeostasis in the intraerythrocytic malaria parasite by an O-3-hexose derivative. FEBS Lett. 2004, 570, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witschel, M.C.; Rottmann, M.; Schwab, A.; Leartsakulpanich, U.; Chitnumsub, P.; Seet, M.; Tonazzi, S.; Schwertz, G.; Stelzer, F.; Mietzner, T.; et al. Inhibitors of Plasmodial Serine Hydroxymethyltransferase (SHMT): Cocrystal Structures of Pyrazolopyrans with Potent Blood- and Liver-Stage Activities. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 3117–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbor-Enoh, S.; Seudieu, C.; Davidson, E.; Dritschilo, A.; Jung, M. Novel Inhibitor of Plasmodium Histone Deacetylase That Cures P. berghei-Infected Mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 1727–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, P.M.; Bray, P.G.; Hawley, S.R.; Ward, S.A.; Park, B.K. 4-Aminoquinolines—Past, present, and future: a chemical perspective. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 77, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharb, R.; Bansal, K. Perspectives on Antimicrobial Potential of Benzothiophene Derivatives. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 1585–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.R.; Meyers, M.J.; Kurumbail, R.G.; Caspers, N.; Poda, G.I.; Long, S.A.; Pierce, B.S.; Mahoney, M.W.; Mourey, R.J. Benzothiophene inhibitors of MK2. Part 1: Structure–activity relationships, assessments of selectivity and cellular potency. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4878–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.R.; Meyers, M.J.; Kurumbail, R.G.; Caspers, N.; Poda, G.I.; Long, S.A.; Pierce, B.S.; Mahoney, M.W.; Mourey, R.J.; Parikh, M.D. Benzothiophene inhibitors of MK2. Part 2: Improvements in kinase selectivity and cell potency. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 4882–4884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsunaga, N.; Kaku, T.; Itoh, F.; Tanaka, T.; Hara, T.; Miki, H.; Iwasaki, M.; Aono, T.; Yamaoka, M.; Kusaka, M.; et al. C17,20-lyase inhibitors I. Structure-based de novo design and SAR study of C17,20-lyase inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 2251–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey, J.; Hu, H.; Kyle, F.; Lai, C.; Buluwela, L.; Coombes, R.C.; Ortlund, E.A.; Ali, S.; Snyder, J.P.; Barrett, A.G.M. Discovery of a New Class of Liver Receptor Homolog-1 (LRH-1) Antagonists: Virtual Screening, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation. ChemMedChem. 2012, 7, 1909–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malamas, M.S.; Sredy, J.; Moxham, C.; Katz, A.; Xu, W.; McDevitt, R.; Adebayo, F.O.; Sawicki, D.R.; Seestaller, L.; Sullivan, D.; et al. Novel Benzofuran and Benzothiophene Biphenyls as Inhibitors of Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B with Antihyperglycemic Properties. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 1293–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Silanes, S.; Berrade, L.; García–Sánchez, R.N.; Mendoza, A.; Galiano, S.; Pérez-Solórzano, B.M.; Nogal-Ruiz, J.J.; Martínez-Fernández, A.R.; Aldana, I.; Monge, A. New 1-Aryl-3-Substituted Propanol Derivatives as Antimalarial Agents. Molecules 2009, 14, 4120–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzić, N.; Konstantinović, J.; Tot, M.; Burojević, J.; Djurković-Djaković, O.; Srbljanović, J.; Štajner, T.; Verbić, T.; Zlatović, M.; Machado, M.; et al. Reinvestigating Old Pharmacophores: Are 4-Aminoquinolines and Tetraoxanes Potential Two-Stage Antimalarials? J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opsenica, I.M.; Verbić, T.Ž.; Tot, M.; Sciotti, R.J.; Pybus, B.S.; Djurković-Djaković, O.; Slavić, K.; Šolaja, B.A. Investigation into novel thiophene- and furan-based 4-amino-7-chloroquinolines afforded antimalarials that cure mice. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 2176–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoroso, F.; Colussi, S.; Del Zotto, A.; Llorca, J.; Trovarelli, A. PdO hydrate as an efficient and recyclable catalyst for the Suzuki–Miyaura reaction in water/ethanol at room temperature. Catal. Commun. 2011, 12, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.D.; Dennull, R.A.; Gerena, L.; Lopez-Sanchez, M.; Roncal, N.E.; Waters, N.C. Assessment and Continued Validation of the Malaria SYBR Green I-Based Fluorescence Assay for Use in Malaria Drug Screening. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 1926–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opsenica, I.; Burnett, J.C.; Gussio, R.; Opsenica, D.; Todorović, N.; Lanteri, C.A.; Sciotti, R.J.; Gettayacamin, M.; Basilico, N.; Taramelli, D.; et al. A Chemotype That Inhibits Three Unrelated Pathogenic Targets: The Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype A Light Chain, P. falciparum Malaria, and the Ebola Filovirus. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1157–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rougemont, M.; van Saanen, M.; Sahli, R.; Hinrikson, H.P.; Bille, J.; Jaton, K. Detection of Four Plasmodium Species in Blood from Humans by 18S rRNA Gene Subunit-Based and Species-Specific Real-Time PCR Assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 5636–5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The inhibition of β-hematin formation is expressed as the molar equivalent of compound, relative to hemin, that inhibits β-hematin formation by 50% and determined by slightly modified BHIA assay introduced by Parapini, S.; Basilico, N.; Pasini, E.; Egan, T.J.; Olliaro, P.; Taramelli, D.; Monti, D. Standardization of the physicochemical parameters to assess in vitro the beta-hematin inhibitory activity of antimalarial drugs. Exp. Parasitol. 2000, 96, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brendle, J.J.; Outlaw, A.; Kumar, A.; Boykin, D.W.; Patrick, D.A.; Tidwell, R.R.; Werbovetz, K.A. Antileishmanial Activities of Several Classes of Aromatic Dications. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 797–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Oh, C.H.; Ko, J.S.; Ahn, K.H.; Kim, Y.J. Zinc-modified cyanoborohydride as a selective reducing agent. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 1927–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musonda, C.C.; Gut, J.; Rosenthal, P.J.; Yardley, V.; Carvalho de Souza, R.C.; Chibale, K. Application of multicomponent reactions to antimalarial drug discovery. Part 2: New antiplasmodial and antitrypanosomal 4-aminoquinoline γ- and δ-lactams via a ‘catch and release’ protocol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 5605–5615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck, R.M.; Preston, R.K.; Creech, H.J. Nitrogen mustard analogs of antimalarial drugs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959, 81, 3984–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C.C.; Leonard, N.J.; Peel, E.W.; Reitsema, R.H. Some 4-amino-7-chloroquinoline derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1946, 68, 1807–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, C.; Malik, H.; Puri, S.K. Synthesis and antimalarial activity of a new series of trioxaquines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opsenica, I.M.; Tot, M.; Gomba, L.; Nuss, J.E.; Sciotti, R.J.; Bavari, S.; Burnett, J.C.; Šolaja, B.A. 4‑Amino-7-chloroquinolines: Probing Ligand Efficiency Provides Botulinum Neurotoxin Serotype A Light Chain Inhibitors with Significant Antiprotozoal Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 5860–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 8, 9, 12, 13, 23–32, 37–44, 46, 52 are available from the authors.

| Structure | In Vitro Antimalarial Activity (P. falciparum, IC50, nM) a,b | HepG2 f (IC50, nM) | SI g HepG2/D6 | RI h W2/D6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D6 c | W2 d | C235 e | |||||

| 8 |  | 20 | 104 | 107 | 8867 | 440 | 5.2 |

| 9 |  | 14 | 191 | 205 | 4867 | 339 | 13.6 |

| 12 |  | 21 | 185 | 191 | 4477 | 211 | 8.8 |

| 13 |  | 16 | 201 | 177 | 2726 | 172 | 12.6 |

| 23 |  | 28 | 144 | 111 | 3825 | 136 | 5.1 |

| 24 |  | 60 | 277 | 242 | 2233 | 37 | 4.6 |

| 25 |  | 71 | 12 | 121 | 2087 | 29 | 0.2 |

| 26 |  | 36 | 55 | 45 | 2345 | 65 | 1.5 |

| 27 |  | 29 | 126 | 126 | 4998 | 173 | 4.3 |

| 28 |  | 6 | 188 | 129 | 2575 | 401 | 31.3 |

| 29 |  | 13 | 44 | 46 | 2413 | 192 | 3.4 |

| 30 |  | 12 | 81 | 51 | 1976 | 162 | 6.8 |

| 31 |  | 13 | 197 | 93 | 3577 | 276 | 15.2 |

| 32 |  | 55 | 102 | 29 | 2049 | 37 | 1.8 |

| CQ i |  | 15 (6) | 595 (5) | 206 (5) | 39.7 | ||

| MFQ i |  | 23 (6) | 7 (5) | 55 (5) | 0.3 | ||

| Structure | In Vitro Antimalarial Activity (P. falciparum, IC50, nM) a,b | HepG2 f (IC50, nM) | SI g HepG2/D6 | RI h W2/D6 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D6 c | W2 d | C235 e | |||||

| 37 |  | 49 | 26 | 60 | > 30605 | 624 | 0.5 |

| 38 |  | 84 | 20 | 43 | 2564 | 30 | 0.2 |

| 39 |  | 59 | 46 | 52 | > 5792 | 98 | 0.8 |

| 40 |  | 80 | 41 | 54 | 6702 | 84 | 0.5 |

| 41 |  | 27 | 13 | 20 | 2415 | 89 | 0.5 |

| 42 |  | 55 | 12 | 30 | 2092 | 38 | 0.2 |

| 43 |  | 4 | 106 | 34 | 8153 | 2038 | 26 |

| 44 |  | 101 | 74 | 54 | 4085 | 40 | 0.7 |

| 46 |  | 7 | 5 | 13 | 2570 | 367 | 0.7 |

| 52 |  | 177 | 259 | 274 | 9230 | 52 | 1.5 |

| CQ i |  | 15 (6) | 595 (5) | 206 (5) | 39.7 | ||

| MFQ i |  | 23 (6) | 7 (5) | 55 (5) | 0.3 | ||

| Comp. | mg/kg/Day | Parasitemia (Day: # Mice, %Parasitemia) | Mice Dead/Day Died | Mice Alive on Day 31 | Mean Survival Time (MST, Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 c | D3: 5 mice positive, 0.6%–2.4%; D7: 2 mice negative, 3 mice positive, 0.1%–0.2%; D11: 3 mice positive, 0.8%–1.9%; D14: 2 mice positive, 1.6%–3.7%; D18: 1 mouse positive, 6%; D21: 1 mouse positive, 27%; D25: 1 mouse positive, 63%; D28: 1 mouse positive, 66% | 2/11 | 0/5 | 16.8 |

| 1/14 | |||||

| 1/18 | |||||

| 1/30 | |||||

| 40 c | D3: 5 mice positive, 0.4%–0.9%; D7: 5 mice negative; D11: 5 mice negative; D14: 5 mice positive, 0.6%–2.4%; D18: 1 mouse positive, 2.2%; D21: 1 mouse positive, 7.3%; D25: 1 mouse positive, 37%; D28: 1 mouse positive, 53% | 1/15 | 0/5 | 19.4 | |

| 1/16 | |||||

| 2/18 | |||||

| 1/30 | |||||

| 80 c | D3: 4 mice positive, 0.7%–1.1%; D7: 4 mice negative; D11: 4 mice negative; D14: 4 mice positive, 0.1%–0.5%; D18: 1 mouse positive, 2.3% | 3/18 | 0/4 | 18.2 | |

| 1/19 | |||||

| 160 | D3: 5 mice positive, 0.3%–0.9%; D7–D31: 5 mice negative | 5/5 | >31 | ||

| 25 | 160 | D3: 4 mice positive, 0.4%–0.6%; D7: 4 mice positive, 0.2%–0.4%; D10: 4 mice positive, 0.3%–0.6%; D14: 4 mice positive, 0.5%–0.8%; D17: 2 mouse positive, 1.5%–3.7%; D21: 1 mouse positive, 2.7%; D24: 1 mouse positive, 52%; D28: 1 mouse positive, 72%; D31: 1 mouse positive, 79% | 2/17 | 1/4 | 20.8 |

| 1/18 | |||||

| 42 | 160 | D3: 5 mice positive, 0.2%–0.6%; D7: 5 mice positive, 0.2%–10%; D10: 4 mice positive, 9.2%–15%; D14: 3 mice positive, 12.8%–47%; D17: 3 mice positive, 50%–60%; D21: 2 mice positive, 64%–70%; D24: 1 mouse positive, 75% | 1/9 | 0/5 | 18.6 |

| 1/13 | |||||

| 1/20 | |||||

| 1/23 | |||||

| 1/28 | |||||

| 46 | 40 c | D3: 5 mice positive, 0.6%–2.2%; D7: 1 mouse negative, 4 mice positive, 0.2%–0.4%; D10: 4 mice positive, 1.6%–4.9%; D14: 2 mice positive, 8.1%–12%; D18: 2 mice positive, 16%–20%; D21: 2 mice positive, 22%–41%; D25: 1 mouse positive, 43% | 1/10 | 0/5 | 15.8 |

| 2/11 | |||||

| 1/22 | |||||

| 1/25 | |||||

| 80 c | D3: 5 mice positive, 0.8%–2.3%; D7: 2 mice negative, 2 mice positive, 0.1%–0.2%; D10: 4 mice positive, 0.2%–6.6%; D14: 1 mouse positive, 4.7%; D18: 1 mouse positive, 12%; D21: 1 mouse positive, 35%; D25: 1 mouse positive, 41% | 1/7 | 0/5 | 14.4 | |

| 1/12 | |||||

| 1/13 | |||||

| 1/14 | |||||

| 1/26 | |||||

| CQ | 160 | D3: 5 mice positive, 0.3%–0.8%; D6-D31: 5 mice negative | 5/5 | >31 | |

| Infected controls | 0 | All mice died on day 7–8 | |||

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Konstantinović, J.; Videnović, M.; Srbljanović, J.; Djurković-Djaković, O.; Bogojević, K.; Sciotti, R.; Šolaja, B. Antimalarials with Benzothiophene Moieties as Aminoquinoline Partners. Molecules 2017, 22, 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22030343

Konstantinović J, Videnović M, Srbljanović J, Djurković-Djaković O, Bogojević K, Sciotti R, Šolaja B. Antimalarials with Benzothiophene Moieties as Aminoquinoline Partners. Molecules. 2017; 22(3):343. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22030343

Chicago/Turabian StyleKonstantinović, Jelena, Milica Videnović, Jelena Srbljanović, Olgica Djurković-Djaković, Katarina Bogojević, Richard Sciotti, and Bogdan Šolaja. 2017. "Antimalarials with Benzothiophene Moieties as Aminoquinoline Partners" Molecules 22, no. 3: 343. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22030343