Synthesis, Spectroscopic Investigations (X-ray, NMR and TD-DFT), Antimicrobial Activity and Molecular Docking of 2,6-Bis(hydroxy(phenyl)methyl)cyclohexanone

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

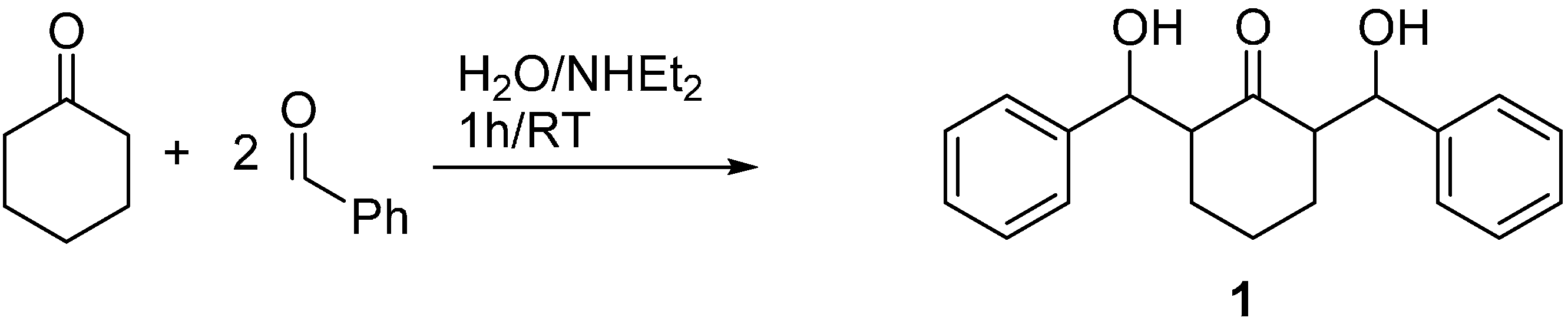

2.1. Synthesis of Compound 1

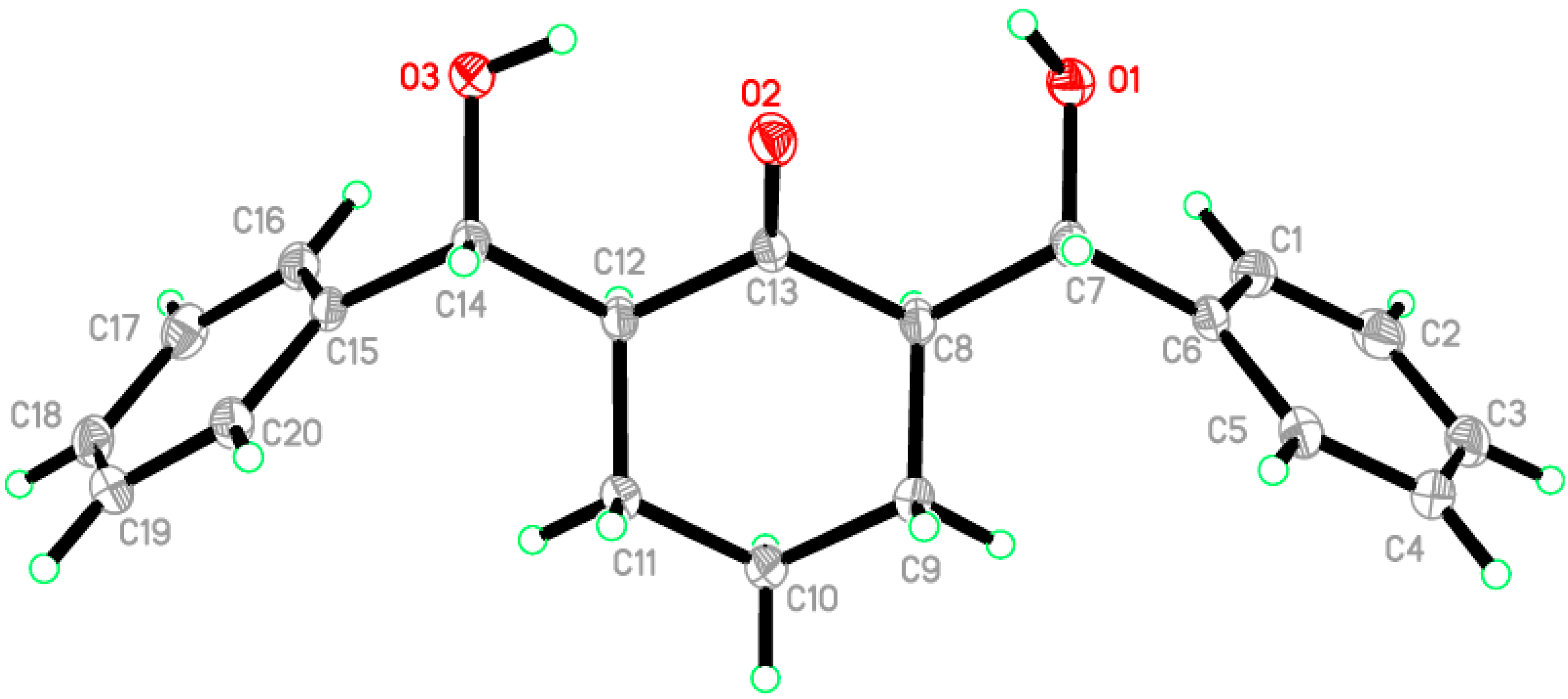

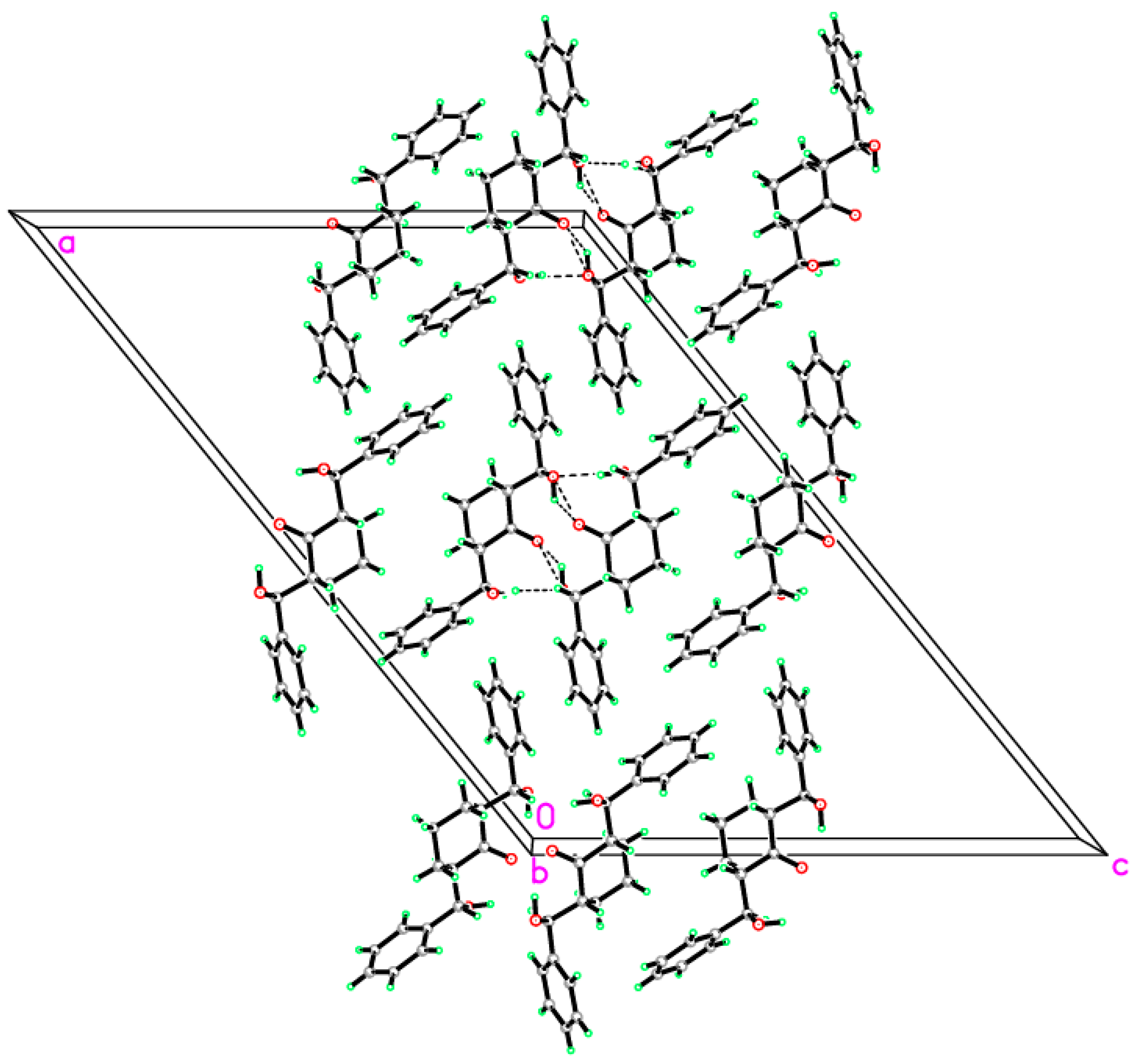

2.2. Crystal Structure of Compound 1

| C20H22O3 | F(000) = 1328 |

|---|---|

| Mr = 310.37 | Dx = 1.284 Mg m−3 |

| Monoclinic, C2/c | Z = 8 |

| a = 32.3262 (14) Å | Mo Kα radiation, λ = 0.71073 Å |

| b = 5.6987 (2) Å | Cell parameters from 9876 reflections |

| c = 22.4859 (7) Å | θ = 2.5–30.6° |

| β = 129.175 (2)° | µ = 0.09 mm−1 |

| V = 3211.2 (2) Å3 | T = 100 K |

| 0.68 × 0.15 × 0.14 mm | Needle, colourless |

| Bruker APEX-II D8 Venture Diffractometer | 3976 Reflections With I > 2σ(I) |

|---|---|

| Radiation source: Mo Kα radiation, λ = 0.71073 Å | Rint = 0.031 |

| φ and ω scans | θmax = 30.6°, θmin = 2.3° |

| Absorption correction: multi-scan SADABS V2012/1 (Bruker AXS Inc., Billerica, MA,USA) | h = −45, 46 |

| Tmin = 0.91, Tmax = 0.99 | k = −7, 8 |

| 34291 measured reflections | l = −32, 31 |

| 4897 independent reflections |

| Refinement on F2 | Hydrogen Site Location: Mixed |

|---|---|

| Least-squares matrix: full | H atoms treated by a mixture of independent and constrained refinement |

| R[F2 > 2σ(F2)] = 0.048 | w = 1/[σ2(Fo2) + (0.0623P)2 + 3.520P] where P = (Fo2 + 2Fc2)/3 |

| wR(F2) = 0.129 | (Δ/σ)max = 0.001 |

| S = 1.03 | Δρmax = 0.62 e·Å−3 |

| 4897 reflections | Δρmin = −0.19 e·Å−3 |

| 216 parameters |

| D—H···A | D—H | H···A | D···A | D—H···A |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1—H1O1···O3 i | 0.90 (2) | 2.01 (2) | 2.8799 (15) | 162.1 (16) |

| O3—H1O3···O2 | 0.90 (3) | 2.07 (2) | 2.7835 (15) | 136 (2) |

| O3—H1O3···O2 i | 0.90 (3) | 2.27 (3) | 2.8491 (17) | 121.9 (18) |

2.3. Computational Details

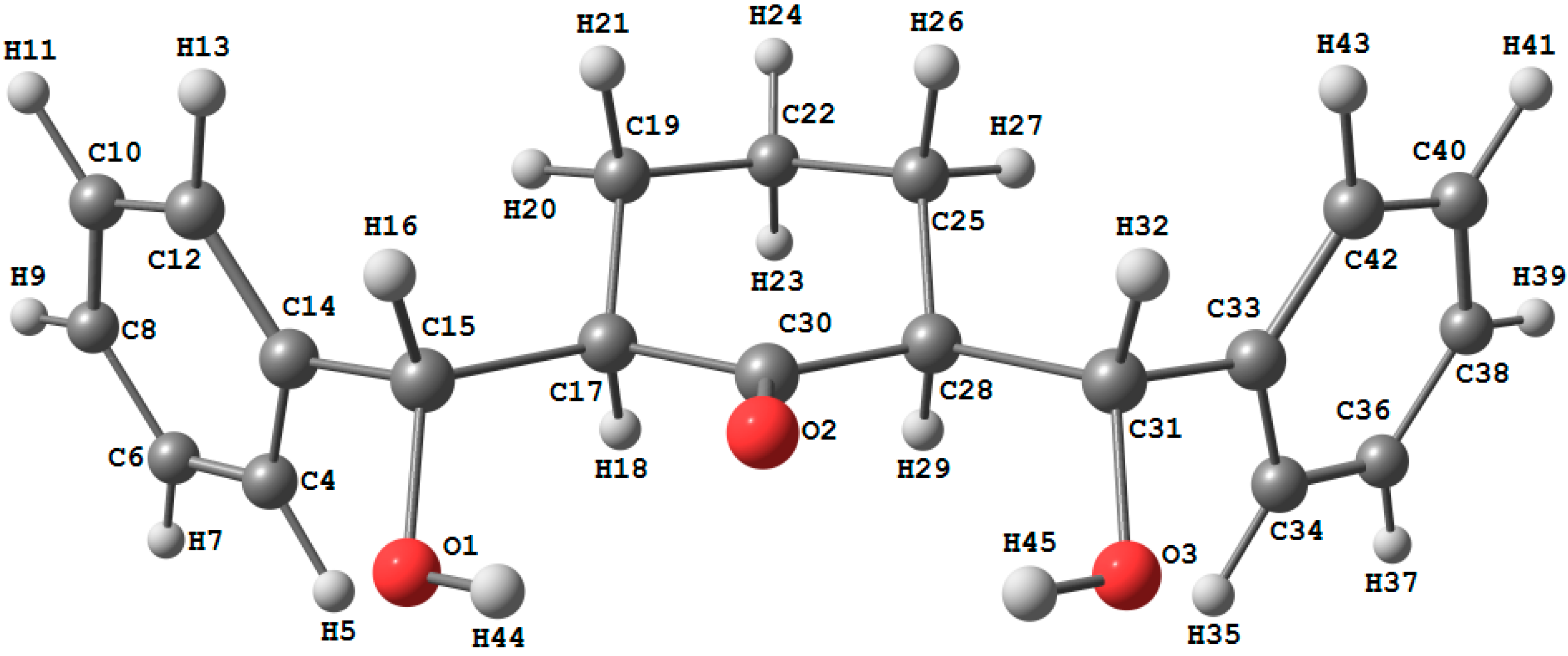

2.3.1. Optimized Molecular Geometry

| Parameter | Calc. | Exp | Parameter | Calc. | Exp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R(1-15) | 1.423 | 1.426 | A(7-6-8) | 120.0 | 119.9 |

| R(2-30) | 1.223 | 1.224 | A(6-8-10) | 119.6 | 119.5 |

| R(3-31) | 1.423 | 1.433 | A(8-10-12) | 120.0 | 120.4 |

| R(4-6) | 1.392 | 1.393 | A(11-10-12) | 119.8 | 119.9 |

| R(4-14) | 1.398 | 1.394 | A(10-12-14) | 120.7 | 120.4 |

| R(6-8) | 1.394 | 1.389 | A(12-14-15) | 121.1 | 120.9 |

| R(8-10) | 1.392 | 1.386 | A(14-15-17) | 112.2 | 112.0 |

| R(10-12) | 1.394 | 1.396 | A(15-17-19) | 114.0 | 113.4 |

| R(12-14) | 1.397 | 1.392 | A(15-17-30) | 112.0 | 112.0 |

| R(14-15) | 1.516 | 1.516 | A(19-17-30) | 109.2 | 108.5 |

| R(15-17) | 1.552 | 1.540 | A(17-19-21) | 109.0 | 109.2 |

| R(17-19) | 1.547 | 1.541 | A(17-30-28) | 116.4 | 116.3 |

| R(17-30) | 1.527 | 1.522 | A(20-19-21) | 106.7 | 108.0 |

| R(19-22) | 1.531 | 1.524 | A(20-19-22) | 110.6 | 109.3 |

| R(22-25) | 1.531 | 1.522 | A(19-22-23) | 109.5 | 109.3 |

| R(25-28) | 1.547 | 1.539 | A(19-22-24) | 109.7 | 109.3 |

| R(28-30) | 1.527 | 1.522 | A(19-22-25) | 111.7 | 111.6 |

| R(28-31) | 1.552 | 1.538 | A(22-25-28) | 112.0 | 111.9 |

| R(31-33) | 1.516 | 1.513 | A(25-28-30) | 109.2 | 109.1 |

| R(33-34) | 1.398 | 1.394 | A(25-28-31) | 114.0 | 111.7 |

| R(33-42) | 1.397 | 1.391 | A(29-28-31) | 107.4 | 107.9 |

| R(34-36) | 1.392 | 1.390 | A(30-28-31) | 112.0 | 112.3 |

| R(36-38) | 1.394 | 1.392 | A(28-31-33) | 112.2 | 110.8 |

| R(38-40) | 1.392 | 1.385 | A(32-31-33) | 108.5 | 108.9 |

| R(40-42) | 1.394 | 1.395 | A(31-33-34) | 120.1 | 120.0 |

| R(2-45) | 2.026 | 2.068 | A(31-33-42) | 121.1 | 120.8 |

| A(1-15-14) | 107.8 | 107.4 | A(34-33-42) | 118.8 | 119.2 |

| A(1-15-16) | 110.1 | 108.9 | A(33-34-36) | 120.5 | 120.4 |

| A(1-15-17) | 110.5 | 110.8 | A(33-42-40) | 120.7 | 120.4 |

| A(2-30-17) | 121.8 | 122.0 | A(33-42-43) | 119.6 | 119.8 |

| A(2-30-28) | 121.8 | 121.7 | A(35-34-36) | 120.4 | 119.7 |

| A(3-31-28) | 110.5 | 111.3 | A(34-36-37) | 119.7 | 119.9 |

| A(3-31-32) | 110.1 | 108.9 | A(34-36-38) | 120.3 | 120.1 |

| A(3-31-33) | 107.8 | 107.9 | A(36-38-40) | 119.6 | 119.8 |

| A(6-4-14) | 120.5 | 120.6 | A(39-38-40) | 120.2 | 120.1 |

| A(4-6-7) | 119.7 | 119.9 | A(38-40-42) | 120.0 | 120.1 |

| A(4-6-8) | 120.3 | 120.2 | A(30-2-45) | 99.6 | 95.6 |

| A(4-14-12) | 118.8 | 118.9 | A(3-45-2) | 131.2 | 136.0 |

| A(4-14-15) | 120.1 | 120.2 |

2.3.2. Natural Atomic Charge

| Atom | NAC | Atom | NAC |

|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | −0.7486 | H24 | 0.2056 |

| O2 | −0.6239 | C25 | −0.3775 |

| O3 | −0.7486 | H26 | 0.1879 |

| C4 | −0.1952 | H27 | 0.2196 |

| H5 | 0.2157 | C28 | −0.3173 |

| C6 | −0.1898 | H29 | 0.2258 |

| H7 | 0.2006 | C30 | 0.6563 |

| C8 | −0.2010 | C31 | 0.1467 |

| H9 | 0.2003 | H32 | 0.1714 |

| C10 | −0.1939 | C33 | −0.0406 |

| H11 | 0.2005 | C34 | −0.1952 |

| C12 | −0.2057 | H35 | 0.2157 |

| H13 | 0.1993 | C36 | −0.1898 |

| C14 | −0.0406 | H37 | 0.2006 |

| C15 | 0.1467 | C38 | −0.2010 |

| H16 | 0.1714 | H39 | 0.2003 |

| C17 | −0.3172 | C40 | −0.1939 |

| H18 | 0.2258 | H41 | 0.2005 |

| C19 | −0.3776 | C42 | −0.2057 |

| H20 | 0.2196 | H43 | 0.1993 |

| H21 | 0.1879 | H44 | 0.4719 |

| C22 | −0.3674 | H45 | 0.4719 |

| H23 | 0.1897 |

2.3.3. Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP)

2.3.4. Nonlinear Optical Properties

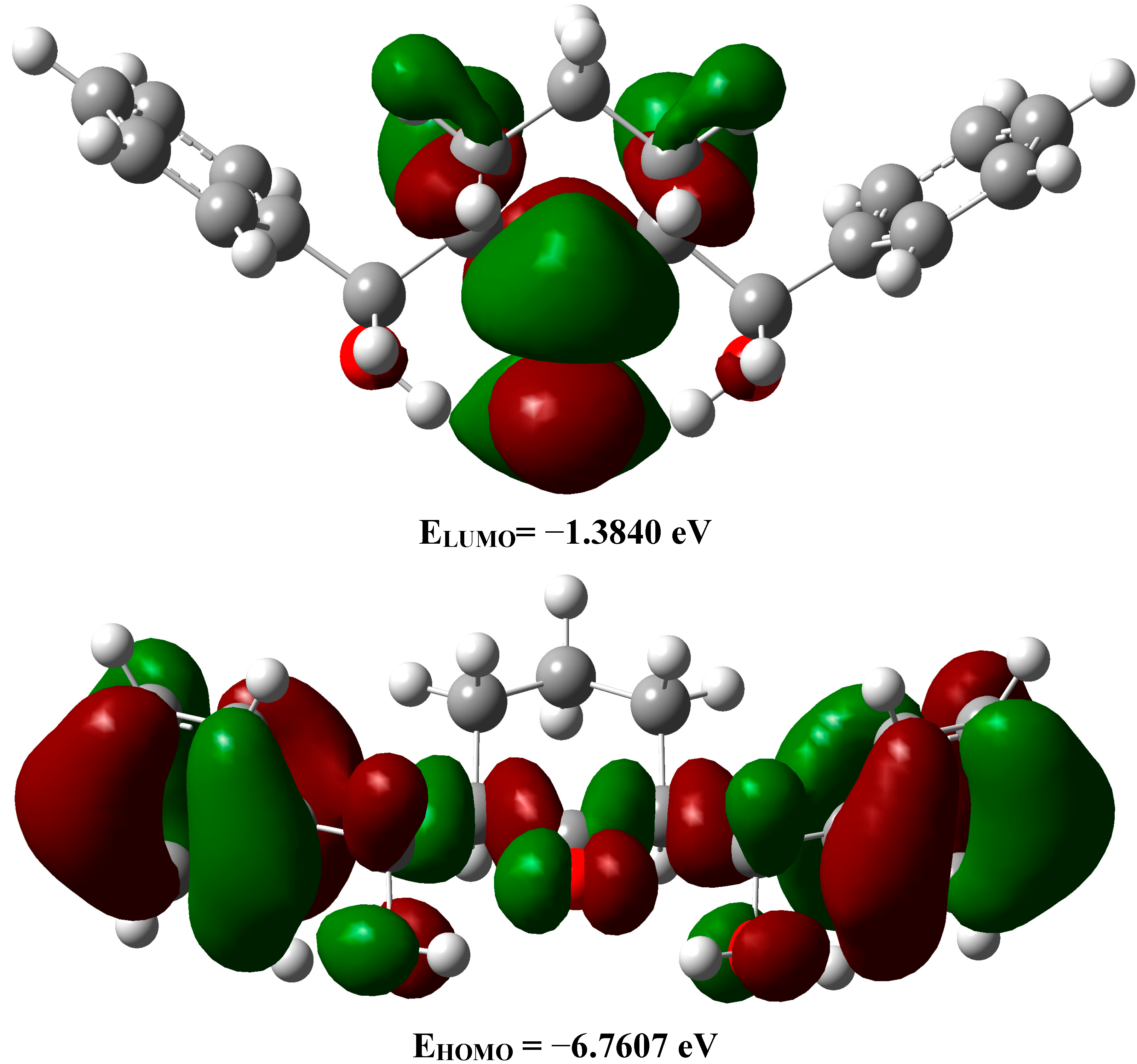

2.3.5. Frontier Molecular Orbitals

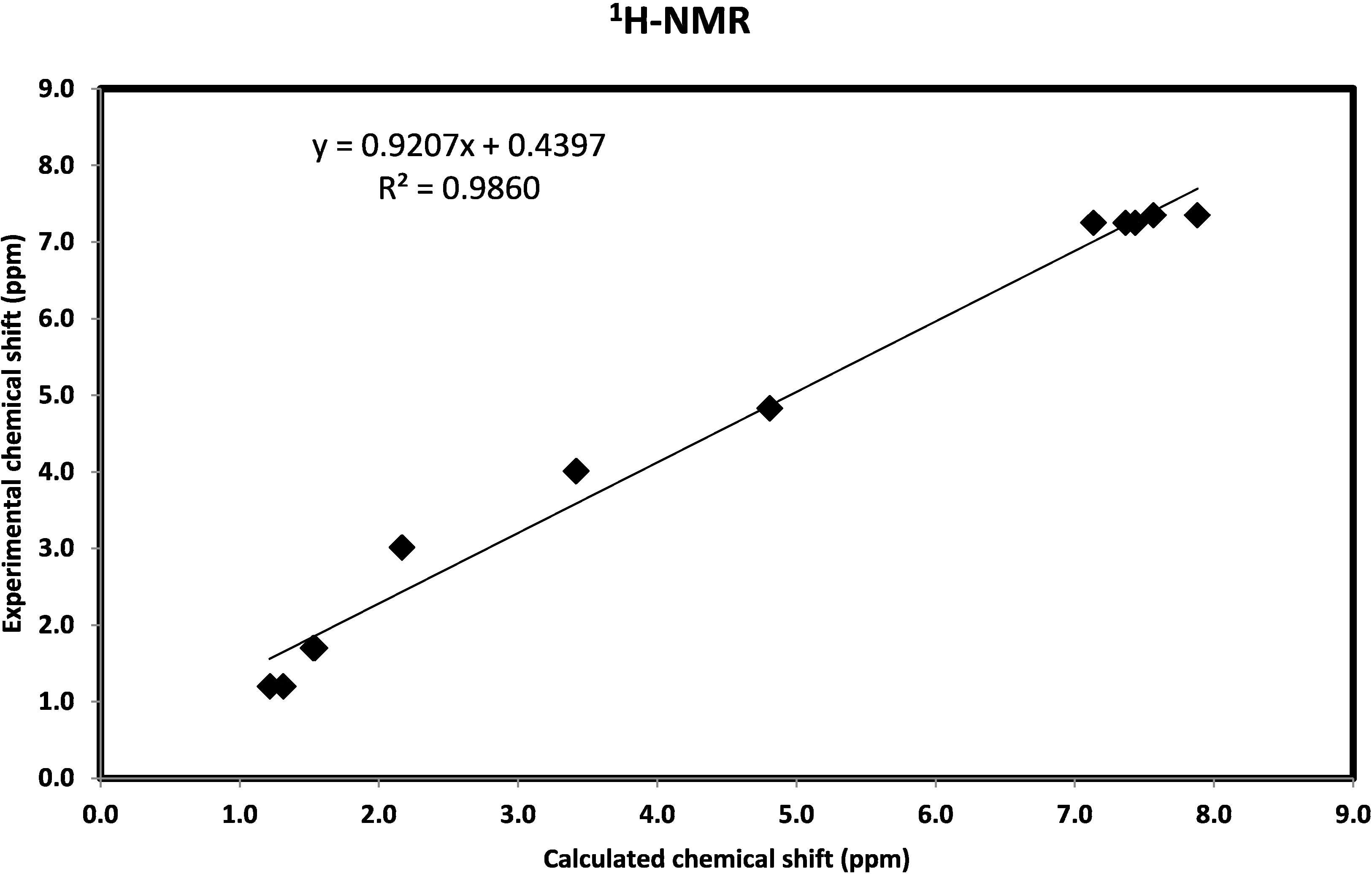

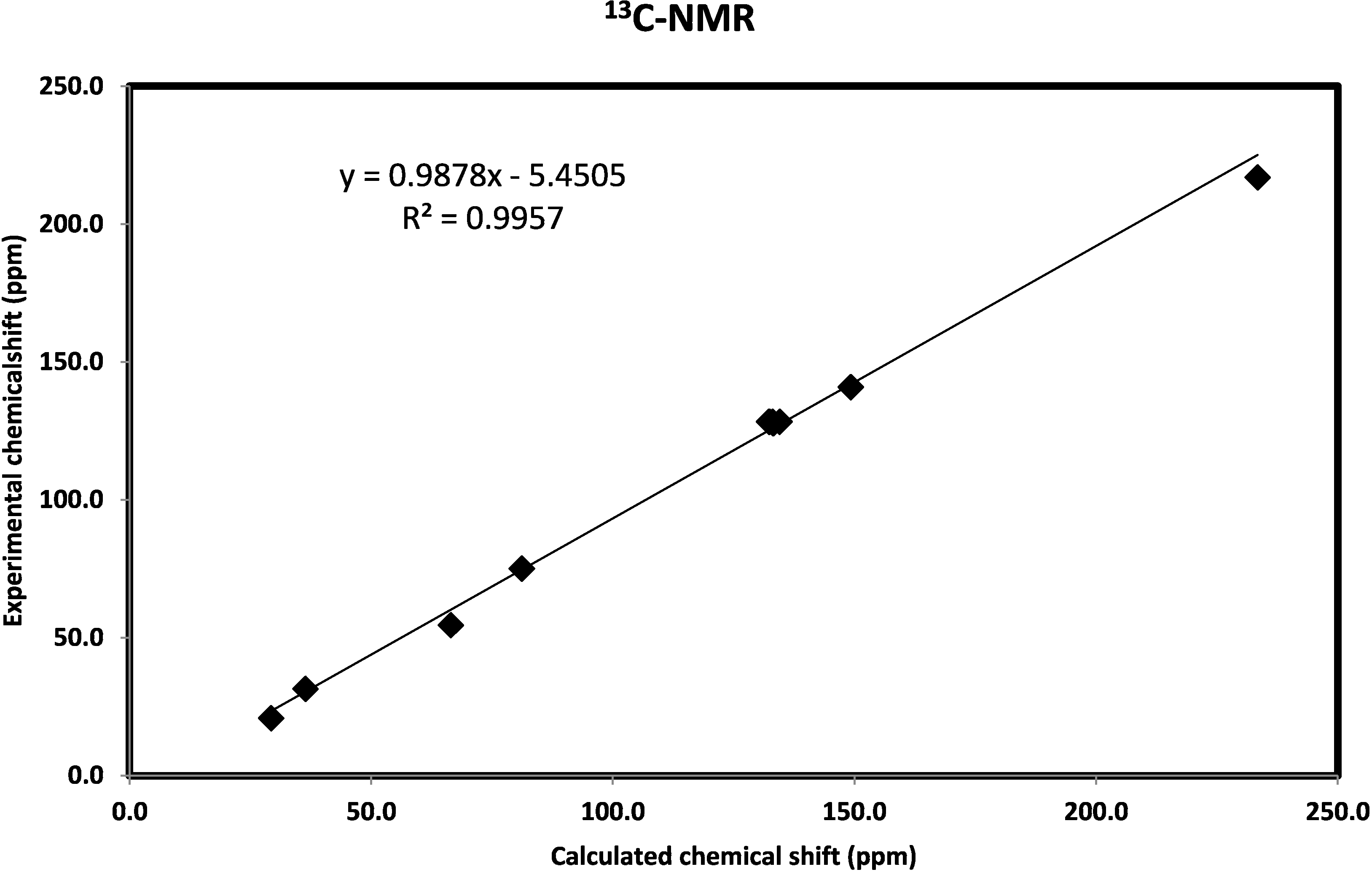

2.3.6. NMR Spectra

2.3.7. Natural Bond Orbital Analysis

Second-Order Perturbation Theory

| Donor NBO (i) | Acceptor NBO (j) | E(2) kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|

| BD(2)C4-C6 | BD*(2)C8-C10 | 20.76 |

| BD(2)C4-C6 | BD*(2)C12-C14 | 21.51 |

| BD(2)C8-C10 | BD*(2)C4-C6 | 20.08 |

| BD(2)C8-C10 | BD*(2)C12-C14 | 19.86 |

| BD(2)C12-C14 | BD*(2)C4-C6 | 19.53 |

| BD(2)C12-C14 | BD*(2)C8-C10 | 21.03 |

| BD(2)C33-C42 | BD*(2)C34-C36 | 19.53 |

| BD(2)C33-C42 | BD*(2)C38-C40 | 21.02 |

| BD(2)C34-C36 | BD*(2)C33-C42 | 21.51 |

| BD(2)C34-C36 | BD*(2)C38-C40 | 20.76 |

| BD(2)C38-C40 | BD*(2)C33-C42 | 19.86 |

| BD(2)C38-C40 | BD*(2)C34-C36 | 20.08 |

| LP(2)O1 | BD*(1)C15-C17 | 6.81 |

| LP(2)O2 | BD*(1)C17-C30 | 18.04 |

| LP(2)O2 | BD*(1)C28-C30 | 18.04 |

| LP(2)O3 | BD*(1)C28-C31 | 6.81 |

| LP(2)O2 | BD*(1)O1-H44 | 2.69 |

| LP(2)O2 | BD*(1)O3-H45 | 2.70 |

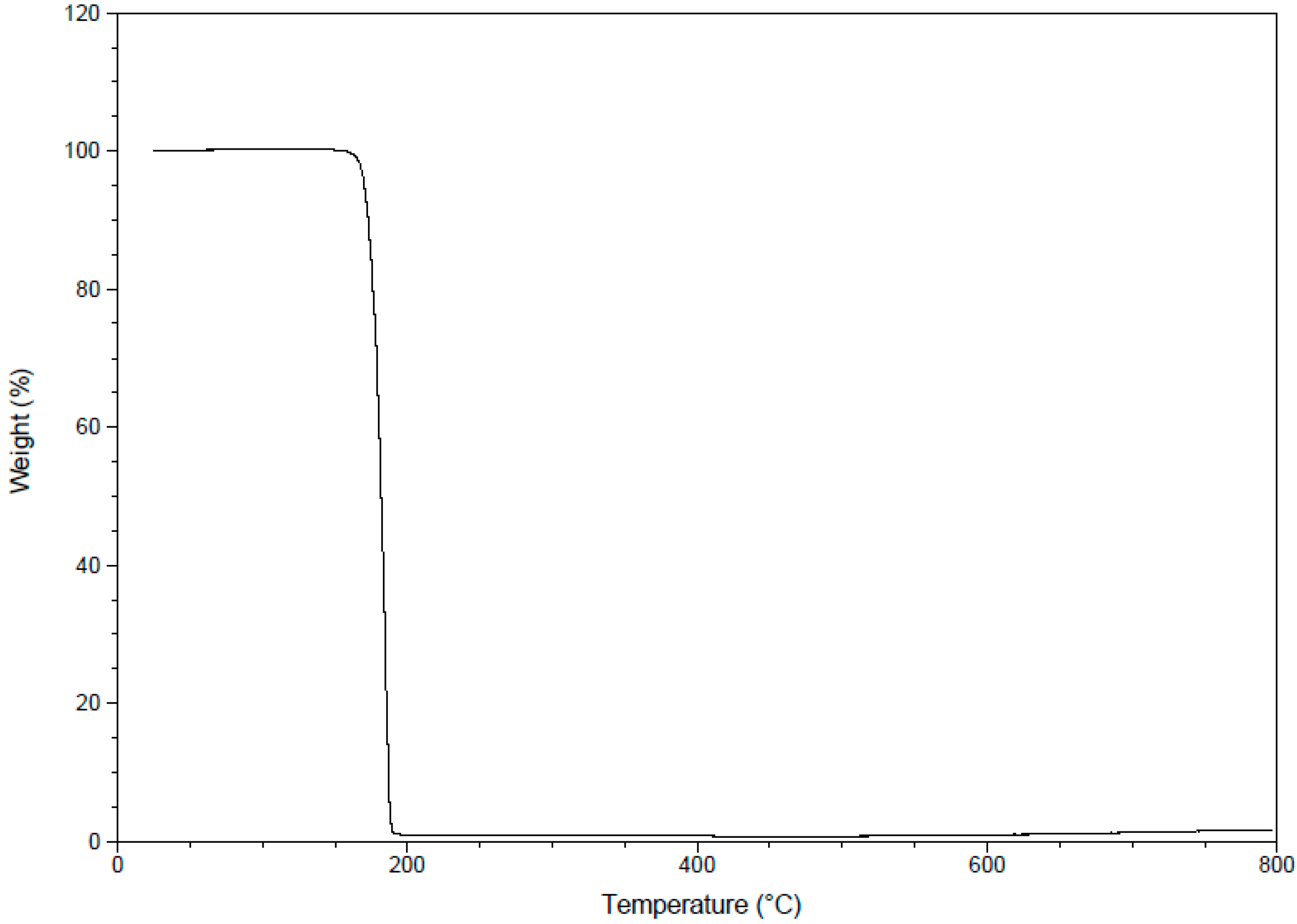

2.3.8. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

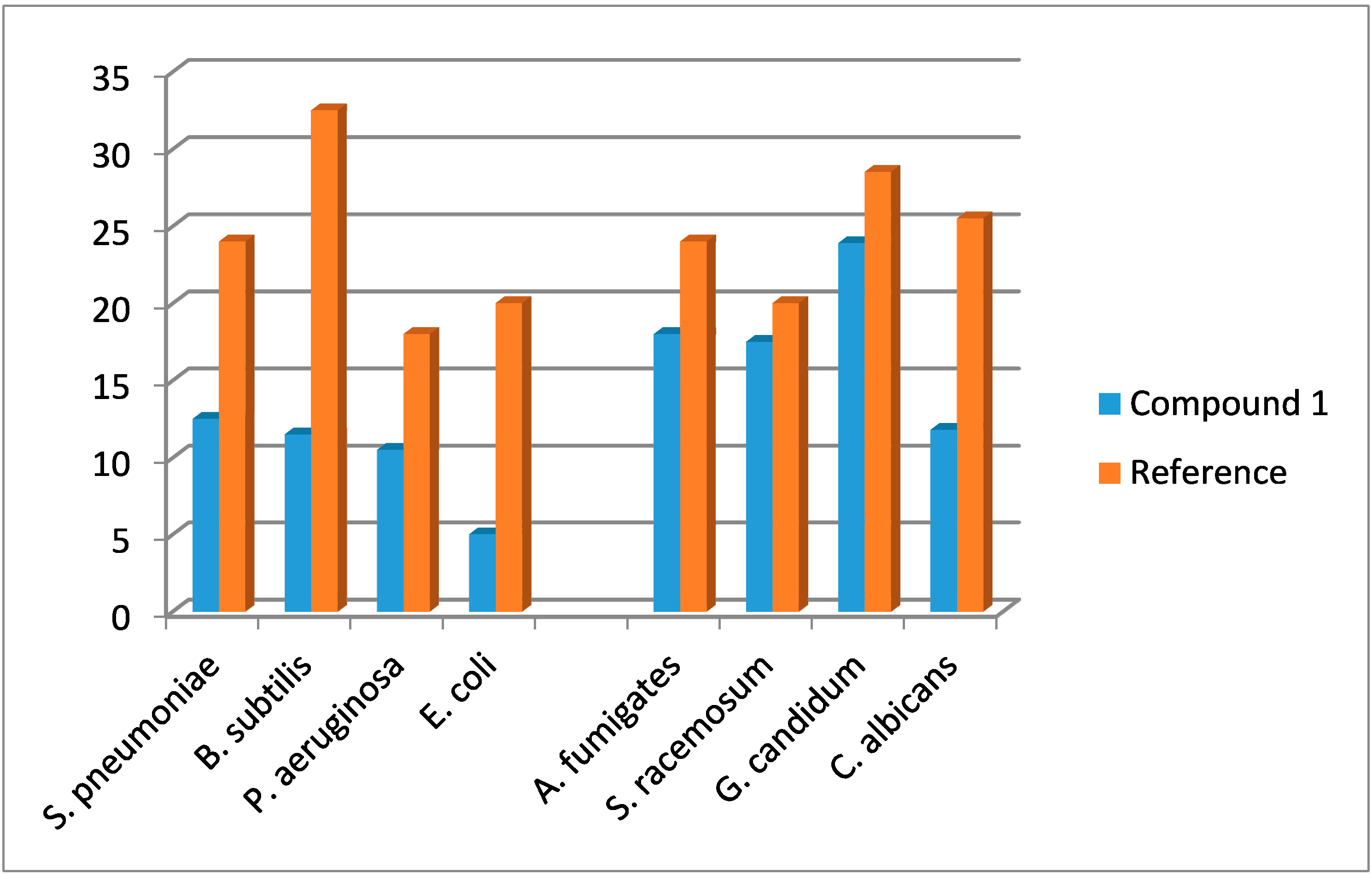

2.4. Antimicrobial Evaluation

| Compound | Gram Positive Bacteria | Gram Negative Bacteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Bacillissubtilis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Escherichia coli | |

| Ampicillin | Gentamicin | |||

| Standard | 24 ± 0.45 | 32.5 ± 0.60 | 18.0 ± 0.15 | 20.0 ± 0.21 |

| 1 | 12.5 ± 0.31 | 11.5 ± 0.31 | 10.5 ± 0.41 | 5.0 ± 0.35 |

| Compound | Fungal Strains | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigates | Syncephalastrum racemosum | Geotricum candidum | Candida albicans | |

| Amphotericin B | ||||

| Standard | 24.0 ± 0.35 | 20.1 ± 0.15 | 28.5 ± 0.45 | 25.5 ± 0.35 |

| 1 | 18.0 ± 0.15 | 17.5 ± 0.40 | 23.9 ± 0.65 | 11.8 ± 0.45 |

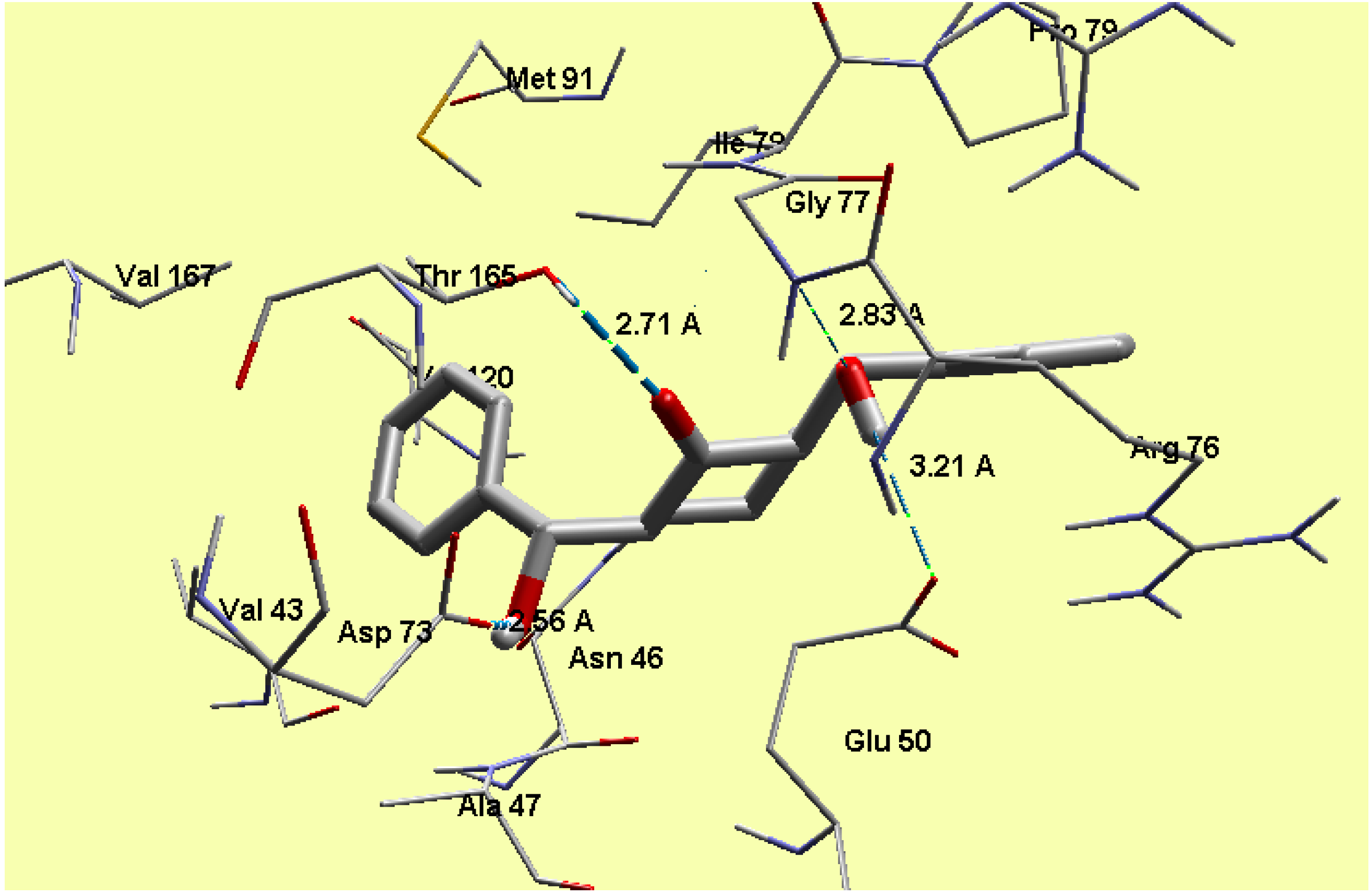

2.5. Molecular Docking

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General

3.2. Preparation of 2,6-Bis(hydroxy(phenyl)methyl)cyclohexanone (1)

3.3. Agar Diffusion Well Method to Determine the Antimicrobial Activity

3.3.1. Antifungal Activity of Compound 1

3.3.2. Antibacterial Activity of Compound 1

3.3. Molecular Docking

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahrwald, R. Modern Aldol Reactions; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004; Volumes 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Dimmock, J.R.; Kumar, P.; Nazarali, A.J.; Motaganahalli, N.L.; Kowalchuk, T.P.; Beazely, M.A.; Quali, J.W.; Oloo, E.O.; Allen, T.M.; Szydlowski, J.; et al. Cytotoxic 2,6-bis(arylidene)cyclohexanones and related compounds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 35, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimmock, J.R.; Padmanilyam, M.P.; Zello, G.A.; Nienaber, K.H.; Allen, T.M.; Santos, C.L.; DeClercq, E.; Balzarini, J.; Manavathu, E.K.; Stables, J.P. Cytotoxic analogues of 2,6-bis(arylidene)cyclohexanones. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 38, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafner, S.; Lee, S.K.; Cuendet, M.; Barthélémy, S.; Vergnes, L.; Labidalle, S.; Mehta, R.G.; Boone, C.W.; Pezzuto, J.M. Biologic evaluation of curcumin and structural derivatives in cancer chemoprevention model systems. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2849–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artico, M.; Santo, R.D.; Costi, R.; Novellino, E.; Greco, G.; Massa, S.; Tramontano, E.; Marongiu, M.E.; Montis, A.D.; Colla, P.L. Geometrically and conformationally restrained cinnamoyl compounds as inhibitors of HIV-1 integrase: Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 3948–3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costi, R.; Santo, R.D.; Artico, M.; Massa, S.; Ragno, R.; Loddo, R.; Colla, M.L.; Tramontano, E.; Colla, P.L.; Pani, A. 2,6-Bis(3,4,5-trihydroxybenzylydene) derivatives of cyclohexanone: Novel potent HIV-1 integrase inhibitors that prevent HIV-1 multiplication in cell-based assays. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piantadosi, C.; Hall, I.H.; Irvine, J.L.; Carlson, G.L. Cycloalkanones. 2. Synthesis and biological activity of α,αʹ-dibenzylcycloalkanones. J. Med. Chem. 1973, 16, 770–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T.P.; Hubbard, R.B.; Ehlers, T.J.; Arbiser, J.L.; Goldsmith, D.J.; Bowen, J.P. Discovery and initial SAR of 2-amino-5-carboxamidothiazoles as inhibitors of the Src-family kinase p56(Lck). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 4007–4010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Abeygunawardana, C.; Talalay, P. Chemoprotective properties of phenylpropenoids, bis(benzylidene)cycloalkanones, and related Michael reaction acceptors: Correlation of potencies as phase 2 enzyme inducers and radical scavengers. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 5287–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, W.M.; Hunsaker, L.A.; Abcouwer, S.F.; Deck, L.M.; Jagt, D.L.V. Anti-oxidant activities of curcumin and related enones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 3811–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, A.A.; Raghunathan, R.; SrideviKumari, M.R.; Raman, N. Synthesis, antimicrobial and antifungal activity of a new class of spiropyrrolidines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2003, 11, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovnyak, G.; Shu, V.; Schwartz, J. Tricyclic thiazolo[3,2-a]thiapyrano[4,3-d]pyrimidines and related analogs as potential anti-inflammatory agents. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1981, 18, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deli, J.; Lorand, T.; Szabo, D.; Foldesi, A. Potentially bioactive pyrimidine derivatives. 2-Amino-4-aryl-8-arylidene-3,4,5,6,7,8-hexahydroquinazoline. Pharmazie 1984, 39, 539–540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Girgis, A.S.; Ibrahim, Y.A.; Mishirky, N.; Lisgarten, J.N.; Potter, B.S.; Palmer, R.A. Regioselective synthetic approaches towards 1,2,8,9-tetraazadispiro[4.1.4.3]tetradeca-2,9-dien-6-ones. Tetrahedron 2001, 57, 2015–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasekara, A.S. Nitrosation of βʹ-hydroxylamino-α,β-unsaturated oximes: Synthesis of 1,7-dioxa-2,6-diaza-spiro[4,4]nona-2,8-diene ring system. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 2635–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathaway, B.A. An aldol condensation experiment using a number of aldehydes and ketones. J. Chem. Educ. 1987, 64, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huitric, A.C.; Kumler, W.D. The Dipole Moments, Spectra and Structure of Some New 2-Phenyl-, 2-Benzyl-, 2-(p-Halobenzylidene)- and 2,6-Bis-(p-halobenzylidene)-cyclohexanones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, I.; Yamamori, T.; Hiramatsu, Y.; Sakai, K.; Mihara, S.; Kawakami, M.; Masui, M.; Uno, O.; Ueda, M. Studies on dihydropyridines. III. Synthesis of 4,7-dihydrothieno [2,3-b]-pyridines with vasodilator and antihypertensive activities. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 4389–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.F.M.M.; Ali, R.; Jahng, Y.; Kadi, A.A. A Facile Solvent Free Claisen-Schmidt Reaction: Synthesis of α,α′-bis-(substituted-benzylidene)cycloalkanones and α,α′-bis-(substituted-alkylidene)cycloalkanones. Molecules 2012, 17, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, T.; Migita, T. A convenient synthesis of α,α′-bis(substitutedbenzylidene)cycloalkanones. Chem. Lett. 1993, 12, 2157–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Irifune, S.J.; Umano, S.; Inada, A.; Ishii, Y.; Ogawa, M. Cross-condensation reactions of cycloalkanones with aldehydes and primary alcohols under the influence of zirconocene complexes. J. Org. Chem. 1987, 52, 2239–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranpoor, N.; Kazemi, F. RuCI3 Catalyses Aldol condensations of aldehydes and ketones. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 9475–9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, L.; Shao, J.; Zhong, Q. A Facile synthesis of α,α′-bis(substituted benzylidene)cycloalkanones catalyzed by bis(p-methoxyphenyl)telluroxide(bmpto) under microwave irradiation. Synth. Commun. 1997, 27, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranpoor, N.; Zeynizadeh, B.; Aghapour, A. Aldol Condensation of Cycloalkanones with Aromatic Aldehydes Catalysed with TiCl3(SO3CF3). J. Chem. Res. Synop. 1999, 9, 554–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ying, T. A Facile Route to Synthesize α,α′-bis(Substituted-benzylidene) Cycloalkanones Promoted by SmI3. Synth. Commun. 1996, 26, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y. SmI3 Catalyzed Condensation of Aliphatic Cycloketones and Aldehydes in Ionic Liquid. Synth. Commun. 2003, 33, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewa, T.; Saiki, T.; Aoyama, Y. Enolization and Aldol Reactions of Ketone with a La3+-Immobilized Organic Solid in Water. A MicroporousEnolase Mimic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 502–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, P.; Khodaei, M.M.; Zolfigol, M.A.; Keyvan, A. Solvent-Free Crossed Aldol Condensation of Ketones with Aromatic Aldehydes Mediated by Magnesium Hydrogensulfate. Monatsh. Chem. 2002, 133, 1291–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J.S.; Reddy, B.V.S.; Nagaraju, A.; Sarma, J.A.R.P. Microwave assisted synthesis of α,α′-bis(benzylidene)ketones in dry media. Synth. Commun. 2002, 32, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.F.; Wang, J.X.; Hu, Y.L. A New solvent-free synthesis of α,α′-dibenzylidenecycloalkanones from acetals with cycloalkanones under microwave irradiation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2003, 14, 333–334. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, X.; Niu, H.; Wang, J. An ionic liquid as a recyclable medium for the green preparation of α,α′-bis (substituted benzylidene)cycloalkanones catalyzed by FeCl3·6H2O. Green Chem. 2003, 5, 267–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabitha, G.; Reddy, G.S.K.K.; Reddy, K.B.; Yadav, J.S. Iodotrimethylsilane-mediated cross-Aldol condensation: A facile synthesis of α,α′-bis(substituted benzylidene)cycloalkanones. Synthesis 2004, 35, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Ren, T. Indium Trichloride catalyzes Aldol-condensations of aldehydes and ketones. Synth. Commun. 2003, 33, 2995–3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.G.; Liu, J.; Zeng, P.L.; Dong, Z.B. Synthesis of α,α′-bis(substituted benzylidene)ketones catalyzed by a SOCl2/EtOH Reagent. J. Chem. Res. Synop. 2004, 1, 55–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Pan, Y. A new Lewis acid system Palladium/TMSCl for catalytic Aldol condensation of aldehydes with ketones. Chem. Lett. 2004, 33, 668–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.Q.; Zhi, D.; Zhang, R.; Chen, B.H. Aldol condensations catalyzed by PEG400 and anhydrous K2CO3 without solvent. Synth. Commun. 2005, 35, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sheng, J.; Tian, H.; Han, J.; Fan, Z.; Qian, C. A convenient synthesis of α,α′-bis(substituted benzylidene)cycloalkanones catalyzed by Yb(OTf)3 under solvent-free conditions. Synthesis 2004, 18, 3060–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Su, W.; Li, N. Copper Triflate-catalyzed cross-Aldol condensation: A facile synthesis of α,α′-bis(substituted benzylidene) cycloalkanones. Synth. Commun. 2005, 35, 3037–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Thirupathi, P.; Mahender, I.; Reddy, K.R. Convenient and facile cross-Aldol condensation catalyzed by molecular iodine: An efficient synthesis of α,α′-bis(substitutedbenzylidene) cycloalkanones. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2006, 247, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, A.; Markert, M.; Mahrwald, R. Amine-Catalyzed Aldol Condensation in the Presence of Lithium Perchlorate. Synthesis 2006, 7, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarkhani, H.; Kumar, P.; Kondiram, K.S.; ShafiGadwal, I.M. Highly selective Claisen-Schmidt condensation catalyzed by silica chloride under solvent-free reaction conditions. Synth. Commun. 2010, 40, 2887–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Chen, X.M.; Pang, L.L.; Ma, R.; Yue, C.-H.; Yuan, R.; Lin, W.; Yin, W.; Bo, R.C.; Wu, H. Synthesis and fluorescence properties of α,α′-bis(substituted-benzylidene)cycloalkanones catalyzed by 1-methyl-3(2-(sulfooxy)ethyl)-1H-imidazol-3-ium chloride. Synth. Commun. 2010, 40, 2320–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasaninejad, A.; Zare, A.; Balooty, L.; Mehregan, M.; Shekouhy, M. Solvent-free, Cross-Aldol condensation reaction using silica-supported, phosphorus-containing reagents leading to α,α′-bis(arylidene)cycloalkanones. Synth. Commun. 2010, 40, 3488–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S.S. Highly anti-Selective Catalytic Aldol reactions of amides with aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 8704–8705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, A.; Al-Najjar, H.J.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Mabkhot, Y.N.; Shaik, M.R.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Fun, H.K. Synthesis, NMR, FT-IR, X-ray structural characterization, DFT analysis and Isomerism aspects of 5-(2,6-dichlorobenzylidene)pyrimidine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2015, 147, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barakat, A.; Al-Najjar, H.J.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Mabkhot, Y.N.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Fun, H.-K. Synthesis, and Molecular characterization, of 5,5′-((2,4-dichlorophenyl)methylene)bis(1,3-dimethylpyrimidine 2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione). J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1084, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Al-Najjar, H.J.; Soliman, S.M.; Al-Agamy, M.H.M.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Fun, H.K. Synthesis, Molecular structure investigations and antimicrobial activity of 2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1081, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, A.; Al-Najjar, H.J.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Adil, S.F.; Ali, M.; Masand, V.H.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Fun, H.K. Synthesis, X-Ray diffraction, thermogravimetric and DFT analyses of pyrimidine Derivatives. Molecules 2014, 19, 17187–17201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008, A64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, A.L. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Cryst. 2009, D65, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruker. SMART and SAINT; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Montgomery, J.A., Jr.; Vreven, T.; Kudin, K.N.; Burant, J.C.; et al. Gaussian‒03, Revision C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- GaussView, Version 4.1; Dennington, R., II; Keith, T.; Millam, J. (Eds.) Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2007.

- Zhurko, G.A.; Zhurko, D.A. Chemcraft. Lite Version Build 08. Available online: http://www.chemcraftprog.com/ (accessed on 20 July 2005).

- Glendening, E.D.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Weinhold, F. NBO Version 3.1, CI; University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kurt, M.; Yurdakul, S. Molecular structure and vibrational spectra of lepidine and 2-chlorolepidine by density functional theory and ab initio Hartree–Fock calculations. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 2005, 730, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.S.; Sen, K. Molecular Electrostatic Potentials, Concepts and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scrocco, E.; Tomasi, J. Electronic molecular structure, reactivity and intermolecular forces: An euristic interpretation by means of electrostatic molecular potentials. Adv. Quantum. Chem. 1978, 11, 115–193. [Google Scholar]

- Galabov, B.; Cheshmedzhieva, D.; Ilieva, S.; Hadjieva, B. Computational study of the reactivity of N-phenylacetamides in the alkaline hydrolysis reaction. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 11457–11462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanasekaran, P.; Madhavan, J. Synthesis, structural, FT-IR and non-linear optical studies of pure and Lanthanum doped L-Arginine acetate single crystals. Asian J. Chem. 2010, 22, 109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Geskin, V.M.; Lambert, C.; Bredas, J.L. Origin of high second- and third-order nonlinear optical response in ammonio/boratodiphenylpolyene zwitterions: The remarkable role of polarized aromatic groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 15651–15658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, L.S. In materials for nonlinear optics, chemical perspectives. ACS Symp. Ser. 1991, 455, 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, K.; Yonezawa, T.; Shingu, H.J. A molecular π orbital theory of reactivity in aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys. 1952, 20, 722–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmaja, L.; Ravikumar, C.; Sajan, D.; Joe, I.H.; Jayakumar, V.S.; Pettit, G.R.; Neilsen, F.O. Density functional study on the structural conformations and intramolecular charge transfer from the vibrational spectra of the anticancer drug combretastatin-A2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2009, 40, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, C.; Joe, I.H.; Jayakumar, V.S. Charge transfer interactions and nonlinear optical properties of push–pull chromophorebenzaldehydephenylhydrazone: A vibrational approach. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008, 460, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, S.; Sundaraganesan, N. The spectroscopic (FT-IR, FT-IR gas phase, FT-Raman and UV) and NBO analysis of 4-Hydroxypiperidine by density functional method. Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2010, 75, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert Joe, I.; Kostova, I.; Ravikumar, C.; Amalanathan, M.; Pinzaru, S.C. Theoretical and vibrational spectral investigation of sodium salt of acenocoumarol. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2009, 40, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Smania, E.F.A.; Monache, F.D.; Smania, A., Jr.; Yunes, R.A.; Cuneo, R.S. Triterpenes and sterols from ganodermaaustrale (Fr) Pat. (Aphyllophoromycetideae). Int. J. Med. Mushrooms. 1999, 1, 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- PDB. A Structural View of Biology. Available online: http://www.rcsb.org/pdb (accessed on 30 March 2015).

- Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD 2013.6.0.0). Molegro Bioinformatics Solutions, 2013, (Danish). Available online: http://www.molegro.com (accessed on 15 April 2015).

- Lafitte, D.; Lamour, V.; Tsvetkov, P.O.; Makarov, A.A.; Klich, M.; Deprez, P.; Moras, D.; Briand, C.; Gilli, R. DNA gyrase interaction with coumarin-based inhibitors: The role of the hydroxybenzoateisopentenyl moiety and the 5ʹ-methyl group of the noviose. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 7217–7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banfi, E.; Scialino, G.; Zampieri, D.; Mamolo, M.G.; Vio, L.; Ferrone, M.; Fermeglia, M.; Paneni, M.S.; Pricl, S. Antifungal and antimycobacterial activity of new imidazole and triazole derivatives. A combined experimental and computational approach. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compound 1 are available from the authors.

© 2015 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barakat, A.; Ghabbour, H.A.; Al-Majid, A.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Ali, M.; Mabkhot, Y.N.; Shaik, M.R.; Fun, H.-K. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Investigations (X-ray, NMR and TD-DFT), Antimicrobial Activity and Molecular Docking of 2,6-Bis(hydroxy(phenyl)methyl)cyclohexanone. Molecules 2015, 20, 13240-13263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200713240

Barakat A, Ghabbour HA, Al-Majid AM, Soliman SM, Ali M, Mabkhot YN, Shaik MR, Fun H-K. Synthesis, Spectroscopic Investigations (X-ray, NMR and TD-DFT), Antimicrobial Activity and Molecular Docking of 2,6-Bis(hydroxy(phenyl)methyl)cyclohexanone. Molecules. 2015; 20(7):13240-13263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200713240

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarakat, Assem, Hazem A. Ghabbour, Abdullah Mohammed Al-Majid, Saied M. Soliman, M. Ali, Yahia Nasser Mabkhot, Mohammed Rafi Shaik, and Hoong-Kun Fun. 2015. "Synthesis, Spectroscopic Investigations (X-ray, NMR and TD-DFT), Antimicrobial Activity and Molecular Docking of 2,6-Bis(hydroxy(phenyl)methyl)cyclohexanone" Molecules 20, no. 7: 13240-13263. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200713240