Bioactive Constituents from the Aerial Parts of Lippia triphylla

Abstract

:1. Introduction

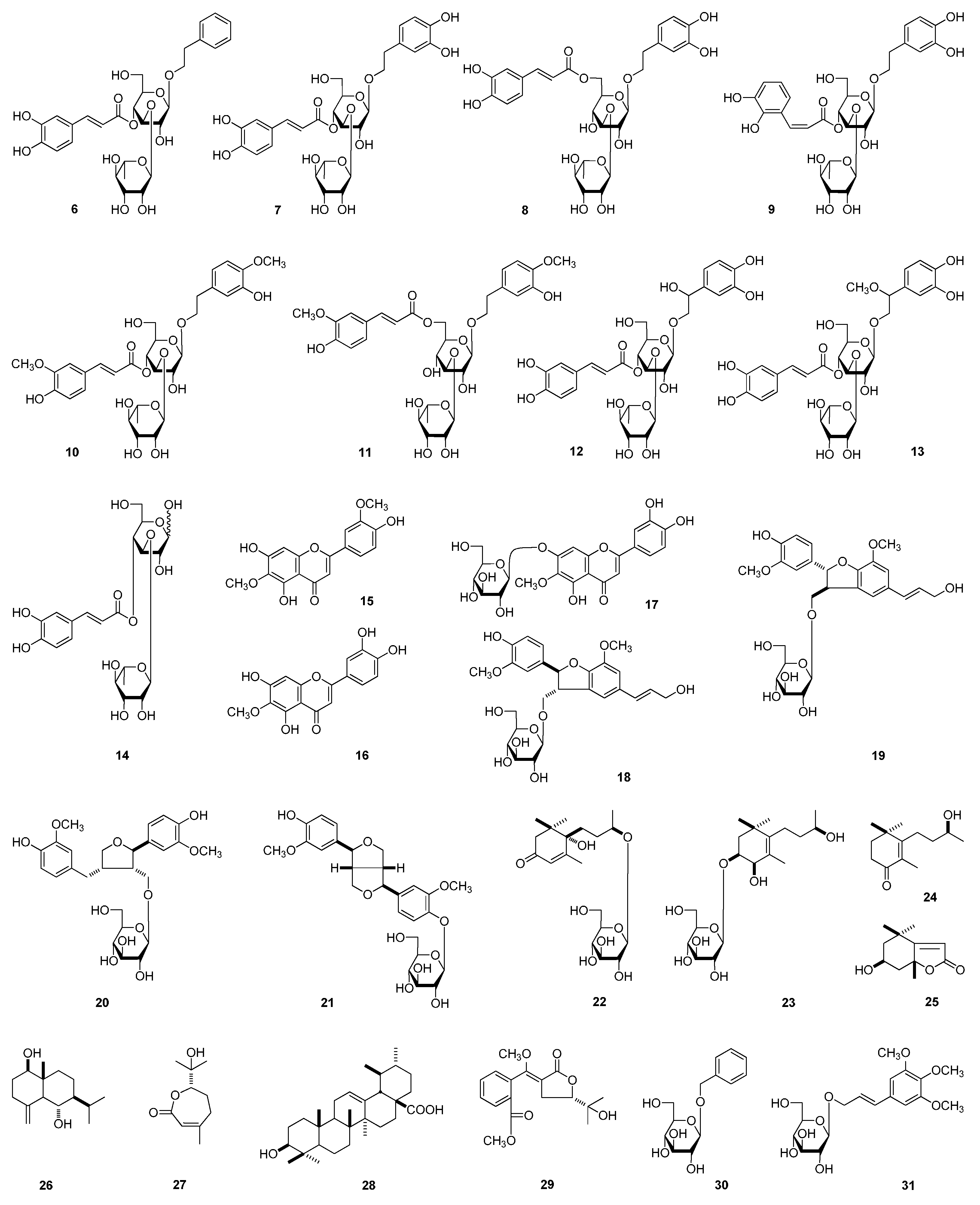

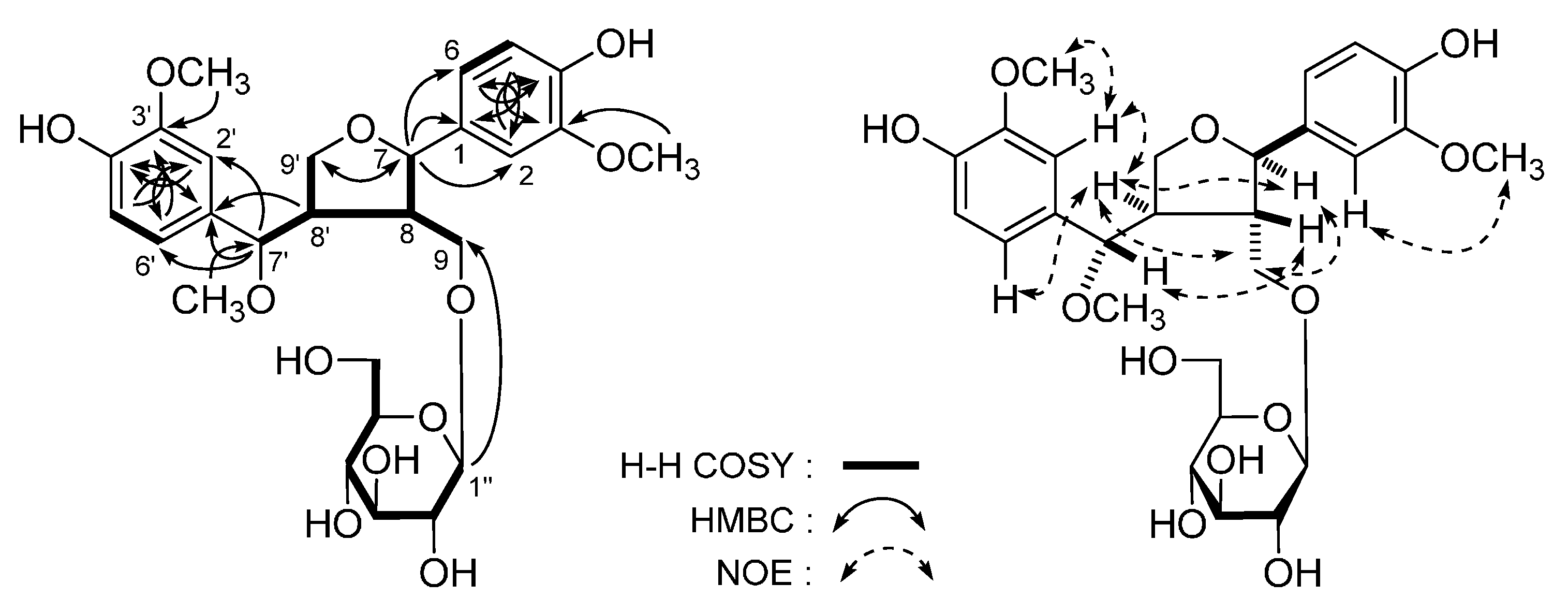

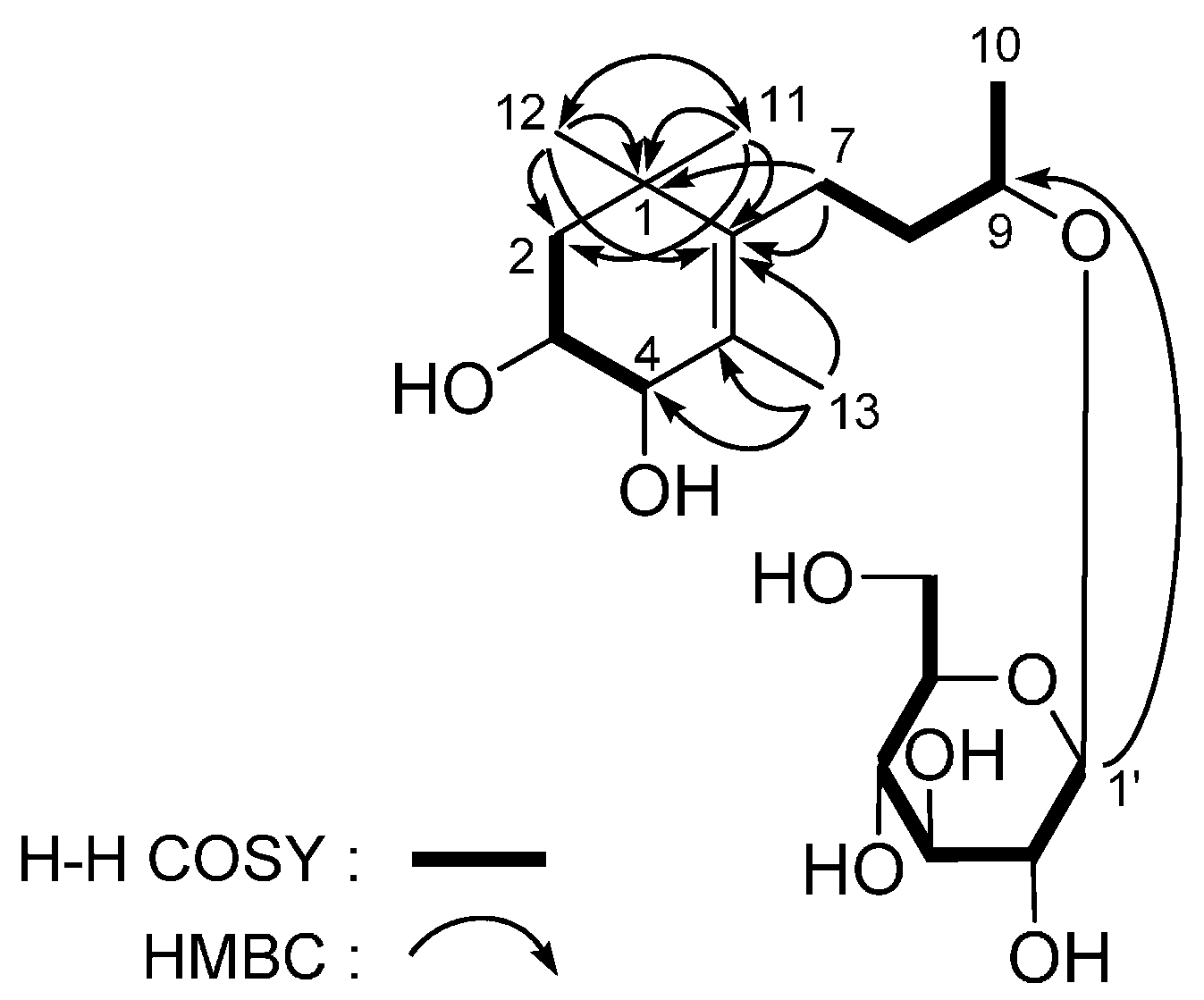

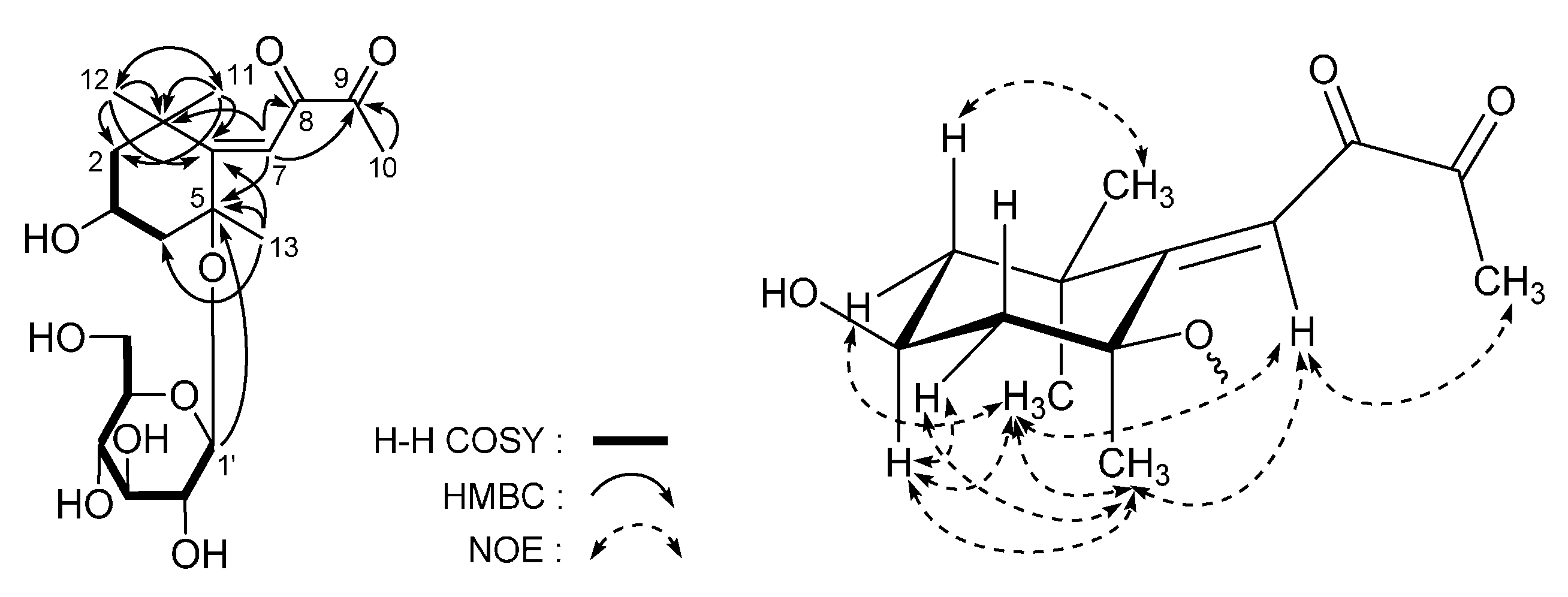

2. Results and Discussion

| No. | 1 a | 1 b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH (J in Hz) | δC | δH (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 133.2 | - | 134.8 | - |

| 2 | 110.4 | 6.88 (d, 2.0) | 111.6 | 6.97 (d, 1.5) |

| 3 | 147.2 | - | 149.0 | - |

| 4 | 145.5 | - | 147.2 | - |

| 5 | 115.0 | 6.71 (d, 8.0) | 116.1 | 6.77 (d, 8.0) |

| 6 | 118.5 | 6.77 (dd, 2.0, 8.0) | 120.3 | 6.86 (dd, 1.5, 8.0) |

| 7 | 82.7 | 4.56 (d, 7.5) | 85.3 | 4.76 (d, 7.0) |

| 8 | 49.7 | 1.75 (m) | 51.6 | 1.96 (m) |

| 9 | 69.5 | 3.75 (m, overlapped) | 70.4 | 3.17 (dd, 4.0, 10.0) |

| 4.05 (dd, 4.5, 9.0) | 3.55 (dd, 6.5, 10.0) | |||

| 3-OCH3 | 55.5 | 3.76 (s) | 56.7 | 3.86 (s) |

| 1′ | 130.7 | - | 132.7 | - |

| 2′ | 110.9 | 6.76 (d, 2.0) | 112.1 | 6.79 (d, 1.5) |

| 3′ | 147.5 | - | 149.3 | - |

| 4′ | 145.9 | - | 147.6 | - |

| 5′ | 115.0 | 6.71 (d, 8.0) | 116.2 | 6.76 (d, 8.5) |

| 6′ | 120.2 | 6.64 (dd, 2.0, 8.0) | 121.8 | 6.70 (dd, 1.5, 8.0) |

| 7′ | 84.5 | 3.97 (d, 7.5) | 87.1 | 4.01 (d, 9.0) |

| 8′ | 48.5 | 2.40 (m) | 50.3 | 2.52 (m) |

| 9′ | 68.7 | 3.11 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) | 71.8 | 3.97 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) |

| 3.46 (dd, 4.0, 9.0) | 4.18 (dd, 4.0, 9.0) | |||

| 3′-OCH3 | 55.7 | 3.73 (s) | 56.6 | 3.82 (s) |

| 7′-OCH3 | 55.4 | 3.07 (s) | 56.7 | 3.16 (s) |

| 1′′ | 102.8 | 3.98 (d, 7.5) | 104.5 | 4.02 (d, 8.0) |

| 2′′ | 73.4 | 2.91 (dd, 7.5, 9.0) | 75.2 | 3.11 (dd, 8.0, 9.0) |

| 3′′ | 76.6 | 3.11 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) | 78.2 | 3.29 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) |

| 4′′ | 69.8 | 3.03 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) | 71.7 | 3.28 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) |

| 5′′ | 76.7 | 3.01 (m) | 77.9 | 3.16 (m) |

| 6′′ | 60.9 | 3.45 (dd, 5.5, 12.5) | 62.8 | 3.66 (dd, 5.5, 12.0) |

| 3.61 (dd, 2.5, 12.5) | 3.82 (dd, 2.5, 12.0) | |||

| No. | δC | δH (J in Hz) | No. | δC | δH (J in Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 98.9 | 4.98 (d, 8.0) | 3′ | 77.8 | 3.43 (dd, 8.5, 9.0) |

| 3 | 152.9 | 7.49 (s) | 4′ | 71.9 | 3.37 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) |

| 4 | 113.3 | - | 5′ | 75.7 | 3.56 (m) |

| 5 | 37.1 | 3.13 (q like, 8.0, 8.0) | 6′ | 64.4 | 4.40 (dd, 6.0, 12.0) |

| 6 | 39.9 | 1.96 (br. dd, ca. 8, 16) | 4.44 (dd, 2.5, 12.0) | ||

| 2.75 (br. dd, ca. 8, 16) | 1′′ | 127.7 | - | ||

| 7 | 128.9 | 5.76 (br. s) | 2′′ | 111.6 | 7.17 (br. s) |

| 8 | 145.0 | - | 3′′ | 149.4 | - |

| 9 | 46.7 | 2.69 (dd, 8.0, 8.0) | 4′′ | 150.7 | - |

| 10 | 61.6 | 4.19 (d, 14.0) | 5′′ | 116.5 | 6.81 (d, 8.0) |

| 4.25 (d, 14.0) | 6′′ | 124.3 | 7.05 (br. d, ca. 8) | ||

| 11 | 171.0 | - | 7′′ | 147.1 | 7.59 (d, 16.0) |

| 1′ | 100.7 | 4.73 (d, 7.5) | 8′′ | 115.3 | 6.35 (d, 16.0) |

| 2′ | 74.8 | 3.27 (dd, 7.5, 8.5) | 9′′ | 169.1 | - |

| 3′′-OCH3 | 56.5 | 3.88 (s) |

| No. | δC | δH (J in Hz) | No. | δC | δH (J in Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70.7 | 3.56 (m) 3.87 (m) | 2′′ | 72.4 | 3.91 (dd, 1.0, 3.0) |

| 2 | 134.6 | 5.47 (m) | 3′′ | 72.1 | 3.57 (dd, 3.0, 9.5) |

| 3 | 125.9 | 5.38 (m) | 4′′ | 73.8 | 3.27 (dd, 9.5, 9.5) |

| 4 | 28.8 | 2.39 (q like, ca. 7) | 5′′ | 70.4 | 3.58 (m) |

| 5 | 21.6 | 2.08 (m) | 6′′ | 18.5 | 1.08 (d, 6.5) |

| 6 | 14.7 | 0.97 (t, 7.5) | 1′′′ | 127.1 | - |

| 1′ | 104.2 | 4.36 (d, 8.0) | 2′′′ | 131.4 | 7.46 (d, 8.5) |

| 2′ | 76.2 | 3.38 (dd, 8.0, 8.5) | 3′′′ | 117.0 | 6.80 (d, 8.5) |

| 3′ | 81.7 | 3.82 (dd, 8.5, 9.0) | 4′′′ | 161.6 | - |

| 4′ | 70.7 | 4.92 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) | 5′′′ | 117.0 | 6.80 (d, 8.5) |

| 5′ | 76.1 | 3.54 (m) | 6′′′ | 131.4 | 7.46 (d, 8.5) |

| 6′ | 62.4 | 3.52 (dd, 6.0, 12.0) | 7′′′ | 147.7 | 7.66 (d, 16.0) |

| 3.62 (br. d, ca. 12) | 8′′′ | 114.8 | 6.34 (d, 16.0) | ||

| 1′′ | 103.1 | 5.19 (d, 1.0) | 9′′′ | 168.4 | - |

| No. | 4 a | 4 b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH (J in Hz) | δC | δH (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 38.8 | - | 37.9 | - |

| 2 | 42.0 | 1.38 (dd, 5.0, 13.0) | 42.4 | 1.72 (dd, 3.0, 12.5) |

| 1.74 (dd, 13.0, 13.0) | 2.20 (dd, 12.5, 12.5) | |||

| 3 | 68.1 | 3.71 (ddd, 4.0, 5.0, 13.0) | 67.1 | 4.12 (ddd, 4.0, 5.5, 12.5) |

| 4 | 73.1 | 3.73 (br. d, ca. 4) | 72.3 | 4.19 (br. d, ca. 4) |

| 5 | 128.1 | - | 128.4 | - |

| 6 | 143.7 | - | 141.6 | - |

| 7 | 25.6 | 1.99 (ddd, 5.0, 13.0, 13.0) | 25.0 | 2.11 (ddd, 4.5, 13.0, 13.0) |

| 2.27 (ddd, 5.0, 13.0, 13.0) | 2.48 (ddd, 4.5, 13.0, 13.0) | |||

| 8 | 38.3 | 1.57 (m), 1.66 (m) | 37.9 | 1.65 (m), 1.85 (m) |

| 9 | 76.1 | 3.90 (m) | 74.8 | 4.14 (m) |

| 10 | 19.8 | 1.20 (d, 6.0) | 19.9 | 1.31 (d, 6.5) |

| 11 | 27.7 | 1.05 (s) | 27.4 | 1.03 (s) |

| 12 | 30.0 | 1.07 (s) | 29.6 | 1.04 (s) |

| 13 | 18.5 | 1.78 (s) | 18.5 | 1.97 (s) |

| 1′ | 102.3 | 4.35 (d, 7.5) | 102.4 | 4.93 (d, 7.5) |

| 2′ | 75.2 | 3.16 (dd, 7.5, 8.5) | 75.2 | 4.04 (dd, 7.5, 8.5) |

| 3′ | 78.2 | 3.36 (dd, 8.5, 9.0) | 78.6 | 4.29 (dd, 8.5, 9.0) |

| 4′ | 71.9 | 3.30 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) | 71.9 | 4.23 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) |

| 5′ | 77.9 | 3.26 (m) | 78.3 | 3.97 (m) |

| 6′ | 63.0 | 3.67 (dd, 5.5, 12.0) | 63.0 | 4.36 (dd, 5.0, 11.5) |

| 3.85 (dd, 2.0, 12.0) | 4.55 (dd, 2.0, 11.5) | |||

| No. | 5 a | 5 b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC | δH (J in Hz) | δC | δH (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 37.1 | - | 35.4 | - |

| 2 | 49.9 | 1.33 (dd, 12.0, 12.0) | 49.1 | 1.21 (dd, 12.5, 12.5) |

| 1.92 (ddd, 2.5, 5.0, 12.0) | 1.79 (ddd, 3.0, 4.5, 12.0) | |||

| 3 | 63.8 | 4.32 (m) | 61.0 | 4.15 (m) |

| 4 | 48.1 | 1.37 (dd, 12.0, 12.0) | 45.9 | 1.19 (dd, 12.0, 12.0) |

| 2.48 (ddd, 2.5, 4.5, 12.0) | 2.38 (ddd, 3.0, 5.0, 12.0) | |||

| 5 | 78.7 | - | 76.9 | - |

| 6 | 141.6 | - | 117.4 | - |

| 6 | 119.1 | - | 117.4 | - |

| 7 | 101.4 | 5.89 (s) | 99.8 | 5.86 (s) |

| 8 | 213.0 | - | 210.6 | - |

| 9 | 200.7 | - | 197.5 | - |

| 10 | 26.7 | 2.19 (s) | 26.2 | 2.12 (s) |

| 11 | 30.1 | 1.37 (s) | 29.0 | 1.29 (s) |

| 12 | 32.5 | 1.15 (s) | 31.7 | 1.05 (s) |

| 13 | 26.6 | 1.47 (s) | 26.3 | 1.33 (s) |

| 1′ | 98.7 | 4.52 (d, 7.5) | 96.8 | 4.36 (d, 7.0) |

| 2′ | 75.3 | 3.14 (dd, 7.5, 9.0) | 73.6 | 2.91 (dd, 7.0, 8.0) |

| 3′ | 78.6 | 3.35 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) | 77.3 | 3.16 (dd, 8.0, 9.0) |

| 4′ | 71.7 | 3.25 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) | 70.1 | 3.01 (dd, 9.0, 9.0) |

| 5′ | 77.8 | 3.22 (m) | 76.6 | 3.06 (m) |

| 6′ | 62.9 | 3.61 (dd, 5.5, 12.0) | 61.1 | 3.37 (dd, 6.0, 12.0) |

| 3.81 (dd, 2.0, 12.0) | 3.62 (dd, 2.0, 12.0) | |||

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, F.S.; Menezes, P.M.; de Sá, P.G.; Oliveira, A.L.; Souza, E.A.; Bamberg, V.M.; de Oliveira, H.R.; de Oliveira, S.A.; Araújo, R.E.; Uetanabaro, A.P.; et al. Pharmacological basis for traditional use of the Lippia thymoides. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herranz-López, M.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Menéndez, J.A.; Joven, J.; Micol, V. Lemon verbena (Lippia citriodora) polyphenols alleviate obesity-related disturbances in hypertrophic adipocytes through AMPK-dependent mechanisms. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 605–614. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, F.S.; Menezes, P.M.; de Sá, P.G.; Oliveira, A.L.; Souza, E.A.; Almeida, J.R.; Lima, J.T.; Uetanabaro, A.P.; Silva, T.R.; Peralta, E.D.; et al. Chemical composition and pharmacological properties of the essential oils obtained seasonally from Lippia thymoides. Pharm. Biol. 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumanayagam, S.; Arunmani, M. Hepatoprotective and antibacterial activity of Lippia nodiflora Linn. against lipopolysaccharides on HepG2 cells. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2015, 11, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajgopal, A.; Rebhun, J.F.; Burns, C.R.; Scholten, J.D.; Balles, J.A.; Fast, D.J. Immunomodulatory effects of Lippia sidoides extract: Induction of IL-10 through cAMP and p38 MAPK-dependent mechanisms. J. Med. Food 2015, 18, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bower, A.M.; Real Hernandez, L.M.; Berhow, M.A.; de Mejia, E.G. Bioactive compounds from culinary herbs inhibit a molecular target for type 2 diabetes management, dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6147–6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balamurugan, R.; Duraipandiyan, V.; Ignacimuthu, S. Antidiabetic activity of γ-sitosterol isolated from Lippia nodiflora L. in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 667, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnat, A.; Carnat, A.P.; Fraisse, D.; Lamaison, J.L. The aromatic and polyphenolic composition of Lemon Verbena tea. Fitoterapia 1999, 70, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaltsa, H.; Shammas, G. Flavonoids from Lippia citriodora. Planta Med. 1988, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, H.; Nishimura, H.; Chin, M.; Chen, Z.; Mitsuhashi, H. Chemical and biological studies on Rehmanniae radix. Part 2. Hydroxycinnamic acid esters of phenethyl alcohol glycosides from Rehmannia glutinosa var. purpurea. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 875–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Long, Q.; Yang, J.; Luo, X. Chemical constituents of Clerodendrum serratum (L.) moon. Shizhen Guoyi Guoyao 2008, 19, 1894–1895. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Deng, R.; Zhao, T.; Yin, W. Studies on chemical constituents of glycosides from Syringa pubescens. Zhongguo Shiyan Fangjixue Zazhi 2011, 17, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Budzianowski, J.; Skrzypczak, L. Phenylpropanoid esters from Lamium album flowers. Phytochemistry 1995, 38, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calis, I.; Lahloub, M.F.; Rogenmoser, E.; Sticher, O. Isomartynoside, a phenylpropanoid glycoside from Galeopsis pubescens. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 2313–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Pan, J. Chemical constituents from leaves of Buddleja officinalis. Tianran Chanwu Yanjiu Yu Kaifa 1997, 9, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Imakura, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Mima, A. Bitter phenyl propanoid glycosides from Campsis chinensis. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Karasawa, H.; Miyase, T.; Fukushima, S. Studies on the constituents of cistanchis herba. V. Isolation and structures of two new phenylpropanoid glycosides, cistanosides E and F. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1985, 33, 1452–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, V.; Barbera, O.; Sanchez-Parareda, J.; Marco, J.A. Phenolic and acetylenic metabolites from Artemisia assoana. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 2619–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, L.; Zheng, S. Chemical constituent analysis of EtOAc fraction of Tithonia diversifolia (HEMSL.) A. Gray. Dier Junyi Daxue Xuebao 2010, 31, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Zhang, X.Q.; Wang, Y.; Ye, W.C. Chemical constituents of the aerial parts of Blumea riparia. Zhongguo Tianran Yaowu 2007, 5, 421–424. [Google Scholar]

- Binns, A.N.; Chen, R.H.; Wood, H.N.; Lynn, D.G. Cell division promoting activity of naturally occurring dehydrodiconiferyl glucosides: do cell wall components control cell division? Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1987, 84, 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, L.S.; Zhan, Z.J.; Yang, S.P.; Yue, J.M. Two new terpenoid glucosides from Aster flaccidus. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 8, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiba, M.; Okabe, K.; Hisada, S.; Shima, K.; Takemoto, T.; Nishibe, S. Elucidation of the structure of a new lignan glucoside from Olea europaea by carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979, 27, 2868–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xuan, Z. Chemical constituents in Folium Forsythia. Zhongguo Yaoshi 2012, 15, 1526–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, R.; Lundgren, L.N. The constituents of conifer needles. Part 13. Monoaryl and cyclohexenone glycosides from needles of Pinus sylvestris. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyase, T.; Ueno, A.; Takizawa, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Oguchi, H. Studies on the glycosides of Epimedium grandiflorum Morr. var. thunbergianum (Miq.) Nakai. III. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 2475–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Otsuka, H.; Hirata, E.; Shinzato, T.; Takeda, Y. Turpinionosides A–E: Megastigmane glucosides from leaves of Turpinia ternata Nakai. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2002, 50, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.C.; Fang, J.M.; Cheng, Y.S. Terpenes and lignans from leaves of Chamaecyparis formosensis. Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, D.; Wahlberg, I.; Nishida, T.; Enzell, C.R. Tobacco chemistry. 50. (3S,5R,8S,9ξ)-5,8-Epoxy-6-megastigmene-3,9-diol and (3S*,5R*,6R*,7E,9ξ)-3,6-epoxy-7-megastigmene-5,9-diol. Two new norcarotenoids of Greek tobacco. Acta Chem. Scand. Ser. B 1979, B33, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machida, K.; Kikuchi, M. Norisoprenoids from Viburnum dilatatum. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.J.; Tan, G.T.; Santarsiero, B.D.; Mesecar, A.D.; van Hung, N.; Cuong, N.M.; Soejarto, D.D.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Fong, H.H.S. New Sesquiterpenes from Litsea verticillata. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Dong, H.; Yang, M. 2-Octenolide as Fungicide and Its Preparation. CN. Patent 103,012,357, 3 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, C.; Zhu, L.; Zhuang, W.; Zhang, L.; He, J.; Li, P.; Li, B. Chemical constituents of stems and leaves of Salvia yunnanensis and their anti-angiogeneic activities. Zhongguo Zhongyao Zazhi 2013, 38, 835–838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Huang, X.; Dahse, H.-M.; Moellmann, U.; Fu, H.; Grabley, S.; Sattler, I.; Lin, W. Unusual naphthoquinone derivatives from the twigs of Avicennia marina. J. Nat. Prod. 2007, 70, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, H.; Li, X.; Xing, S.; Pei, Y. Chemical constituents of Linaria vulgaris. Zhongguo Yaoxue Zazhi 2005, 40, 653–656. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita, H.; Miyase, T.; Ueno, A. Lignan and terpene glycosides from Epimedium sagittatum. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 2025–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, T.; Zhang, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Matsuda, H.; Muraoka, O.; Yoshikawa, M. Bioactive constituents from Chinese natural medicines. XXII. Absolute structures of new megastigmane glycosides, sedumosides E1, E2, E3, F1, F2, and G, from Sedum sarmentosum (Crassulaceae). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007, 55, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Morikawa, T.; Nakamura, S.; Ninomiya, K.; Matsuda, H.; Muraoka, O.; Yoshikawa, M. Bioactive constituents from chinese natural medicines. XXV. New flavonol bisdesmosides, sarmenosides I, II, III, and IV, with hepatoprotective activity from Sedum sarmentosum (Crassulaceae). Heterocycles 2007, 71, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar]

- Machida, K.; Yamauchi, M.; Kurashina, E.; Kikuchi, M. Four new lignan glycosides from Osmanthus fragrans Lour. var. aurantiacus Makino. Helv. Chim. Acta 2010, 93, 2164–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xie, Z.; Gao, H.; Ma, W.; Dai, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yao, X. Bioactive iridoid glucosides from the fruit of Gardenia jasminoides. J. Nat. Prod. 2009, 72, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskernik, C.; Haindl, S.; Behling, T.; Gerald, Z.; Kehrer, I.; Redl, H.; Kozlov, A.V. Antimycin A and lipopolysaccharide cause the leakage of superoxide radicals from rat liver mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1782, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lara-Castro, C.; Garvey, W.T. Intracellular lipid accumulation in liver and muscle and the insulin resistance syndrome. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 37, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sample Availability: Samples of all the compounds are available from the authors.

© 2015 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Dong, Y.; Wang, T.; Qu, L.; Li, N.; Wang, T. Bioactive Constituents from the Aerial Parts of Lippia triphylla. Molecules 2015, 20, 21946-21959. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201219814

Zhang Y, Chen Y, Wang S, Dong Y, Wang T, Qu L, Li N, Wang T. Bioactive Constituents from the Aerial Parts of Lippia triphylla. Molecules. 2015; 20(12):21946-21959. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201219814

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yi, Yue Chen, Shiyu Wang, Yongzhe Dong, Tingting Wang, Lu Qu, Nan Li, and Tao Wang. 2015. "Bioactive Constituents from the Aerial Parts of Lippia triphylla" Molecules 20, no. 12: 21946-21959. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201219814