Six-Membered Aromatic Polyazides: Synthesis and Application

Abstract

:1. Introduction

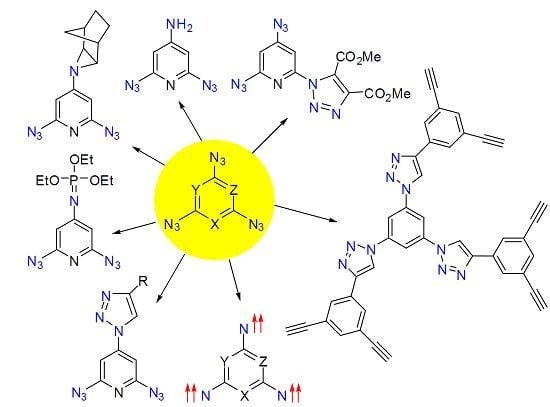

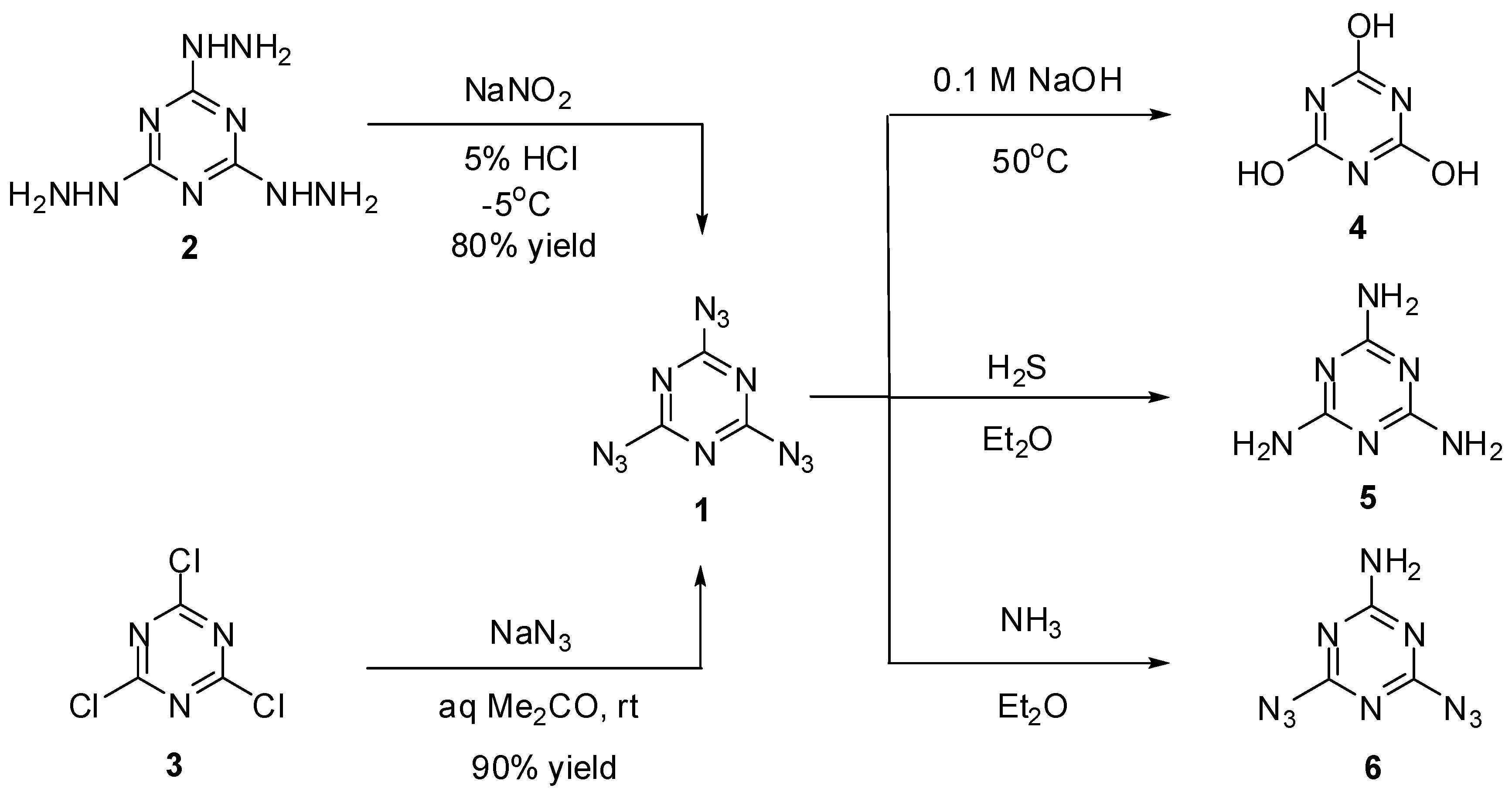

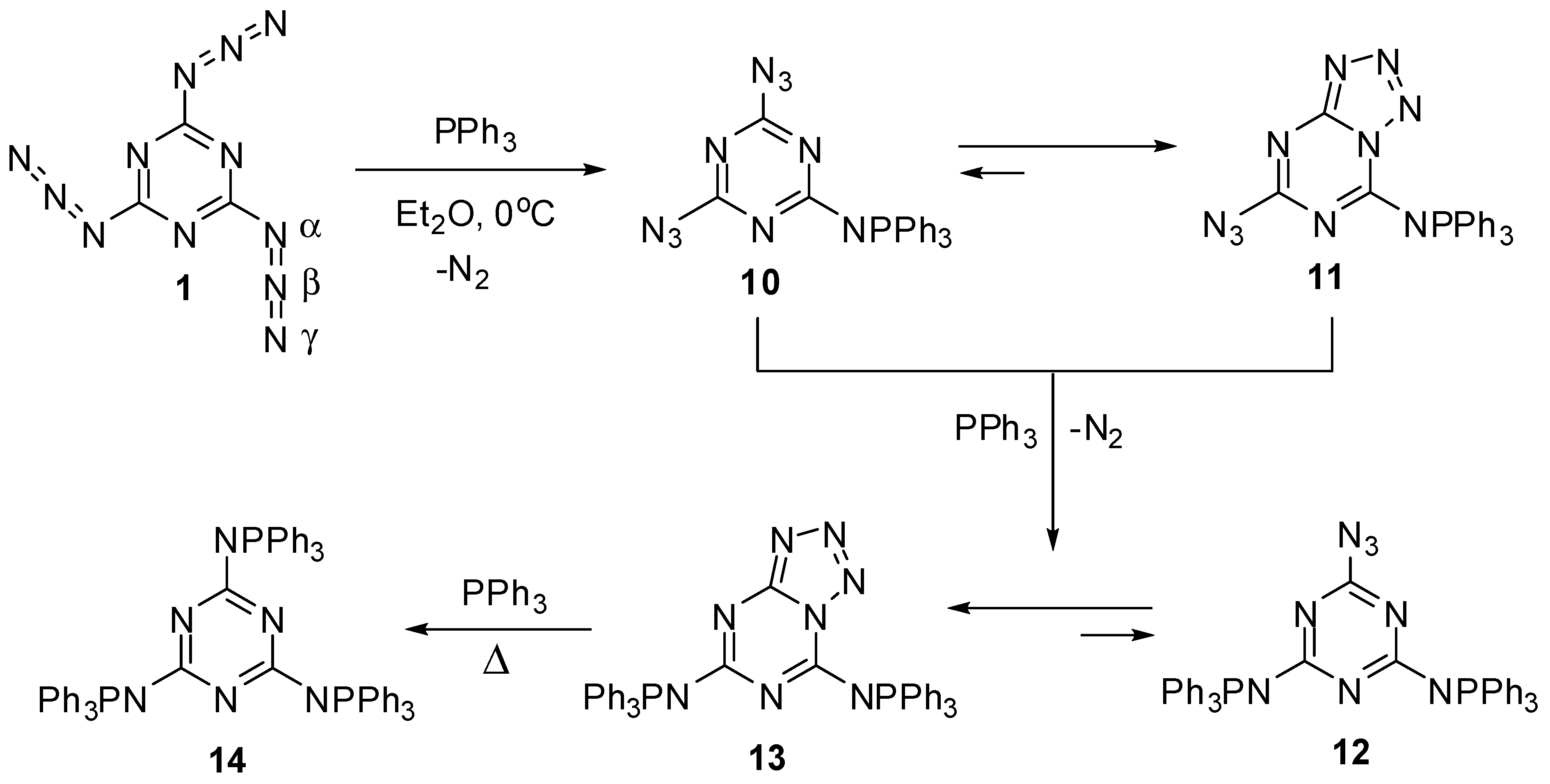

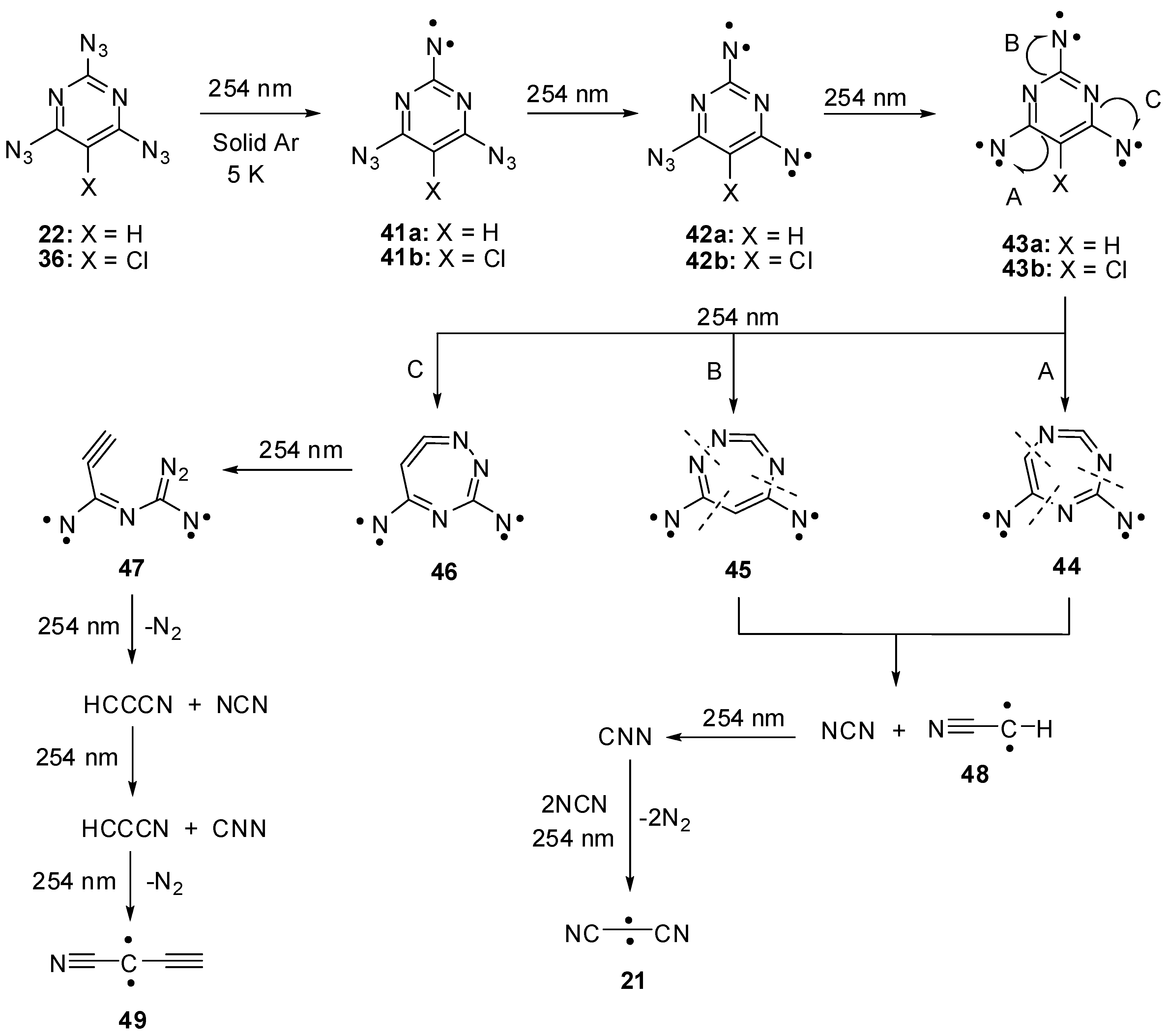

2. Cyanuric Triazide

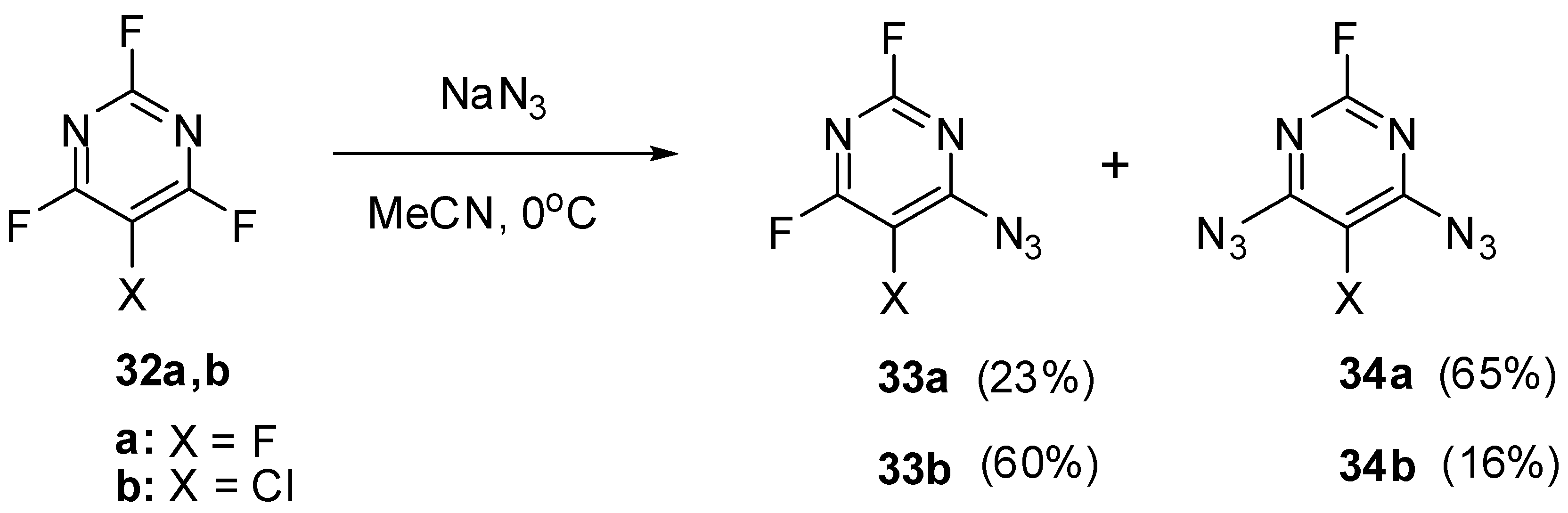

3. Triazidopyrimidines

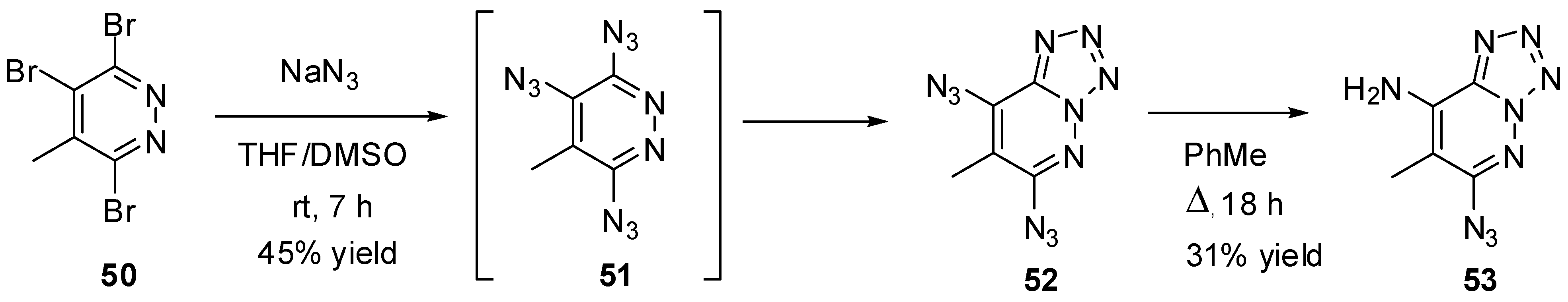

4. Triazidopyridazines

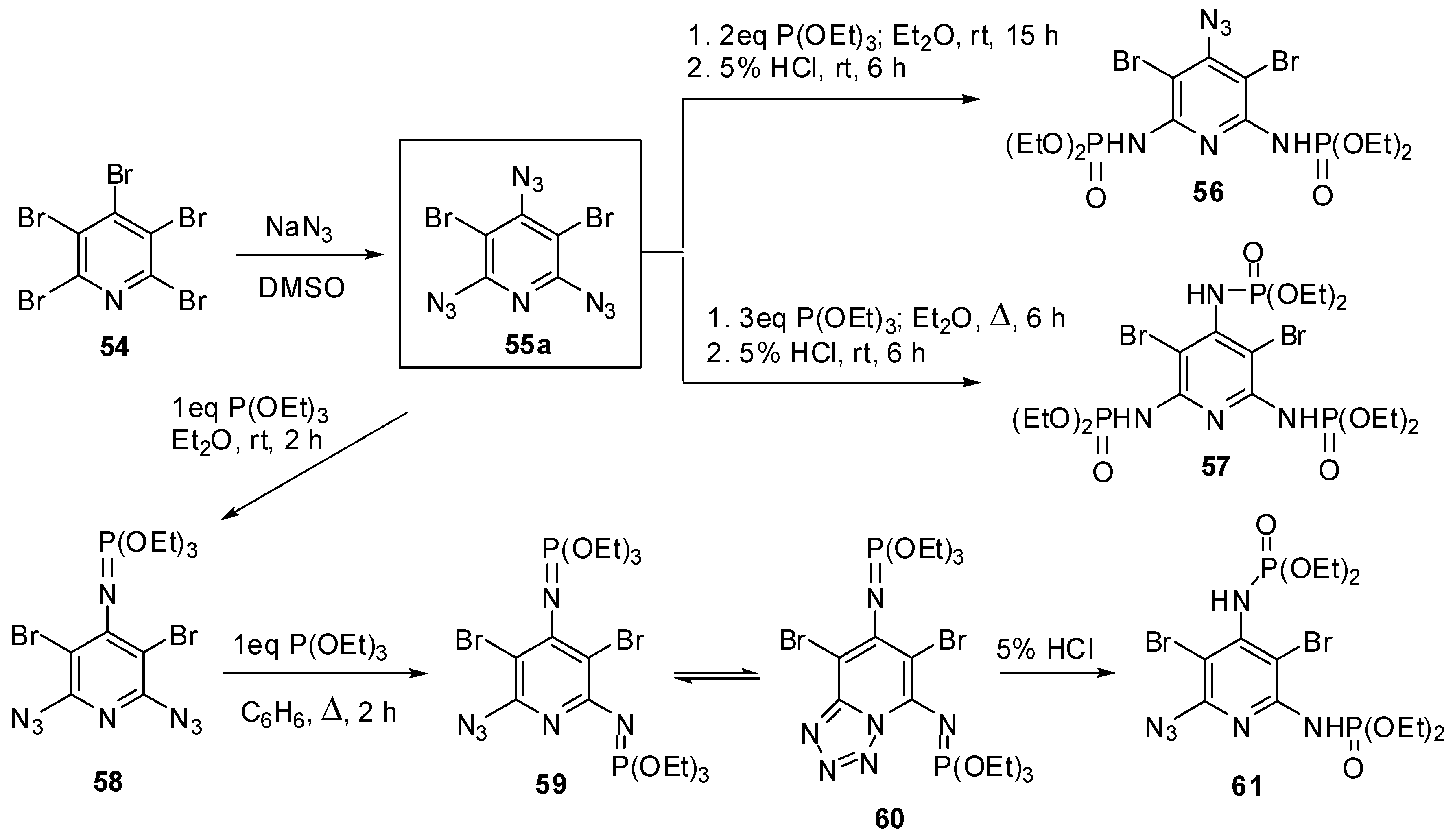

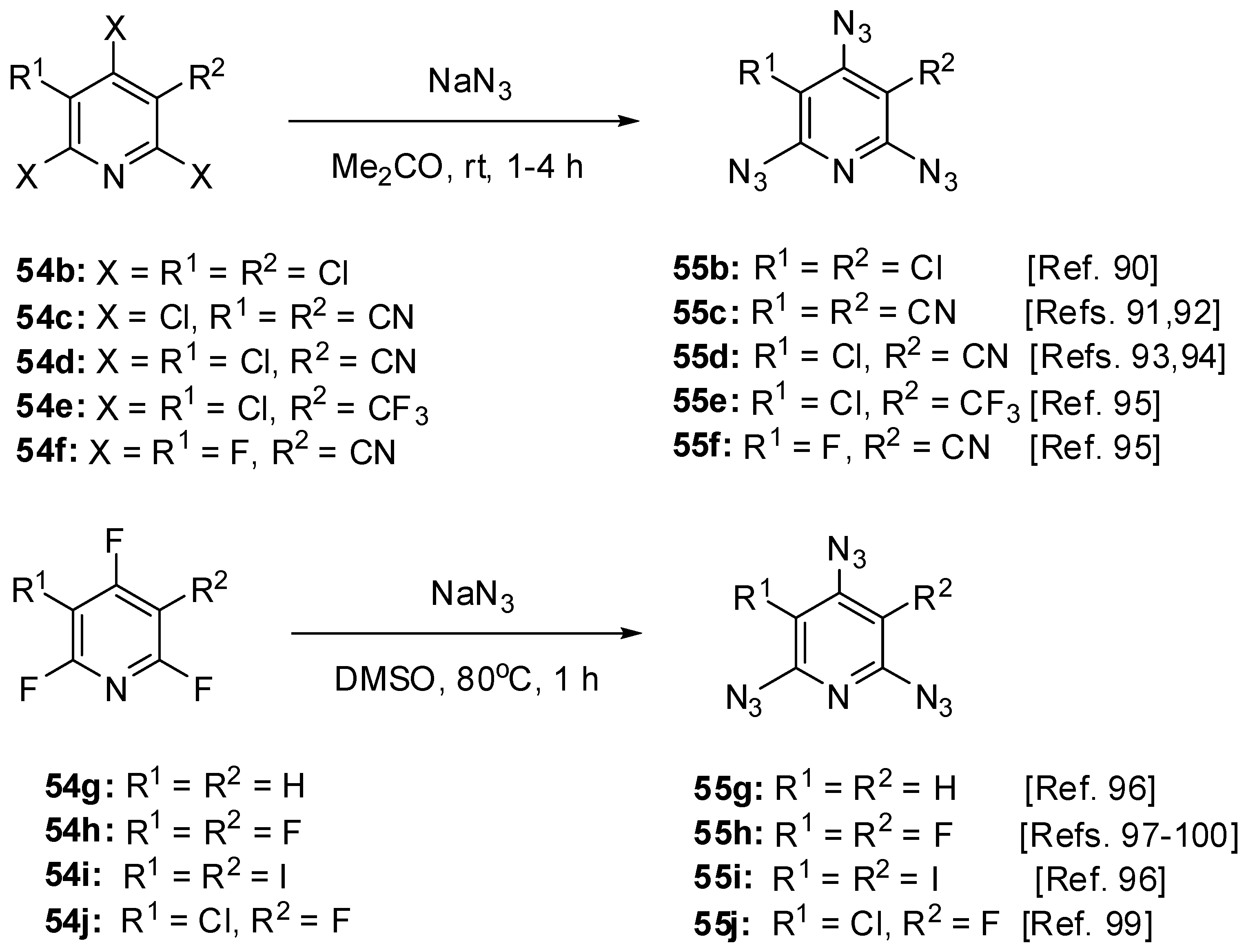

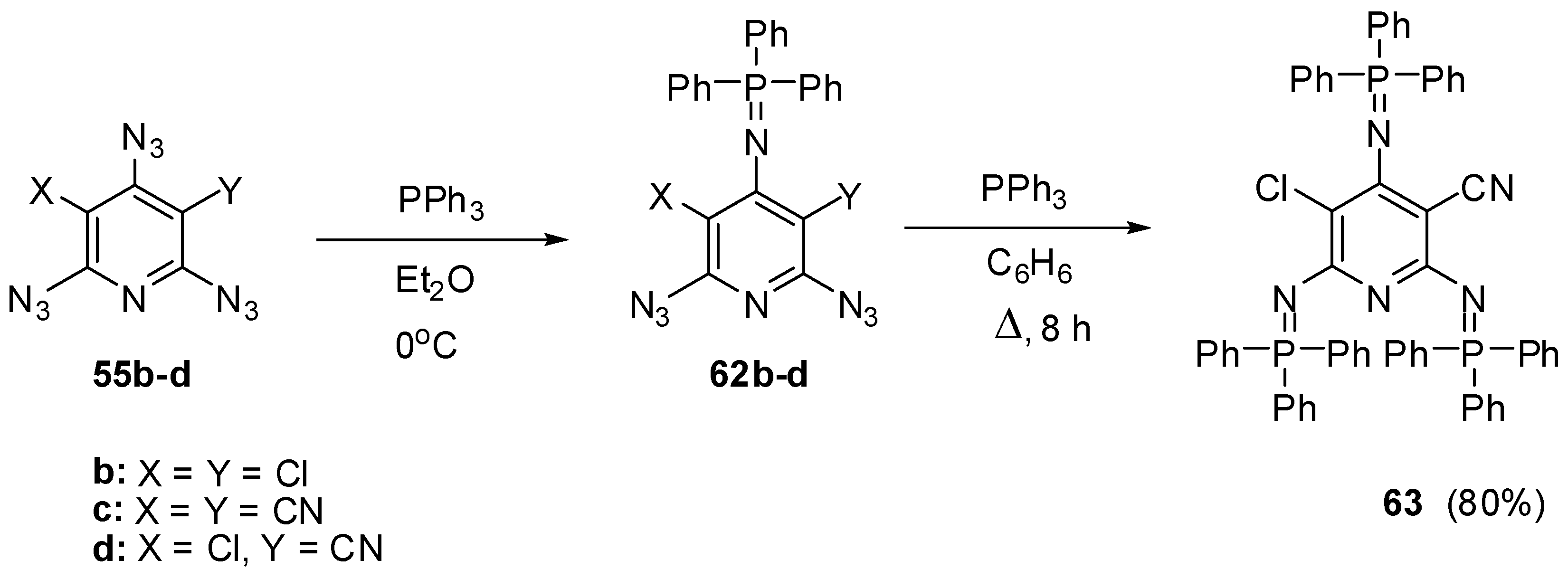

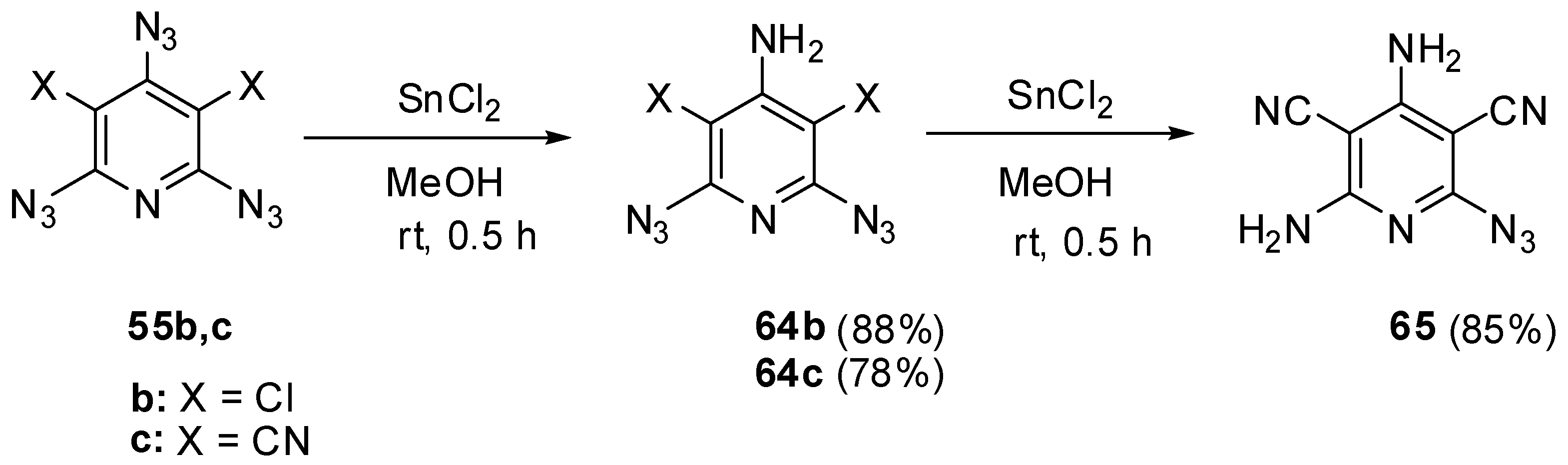

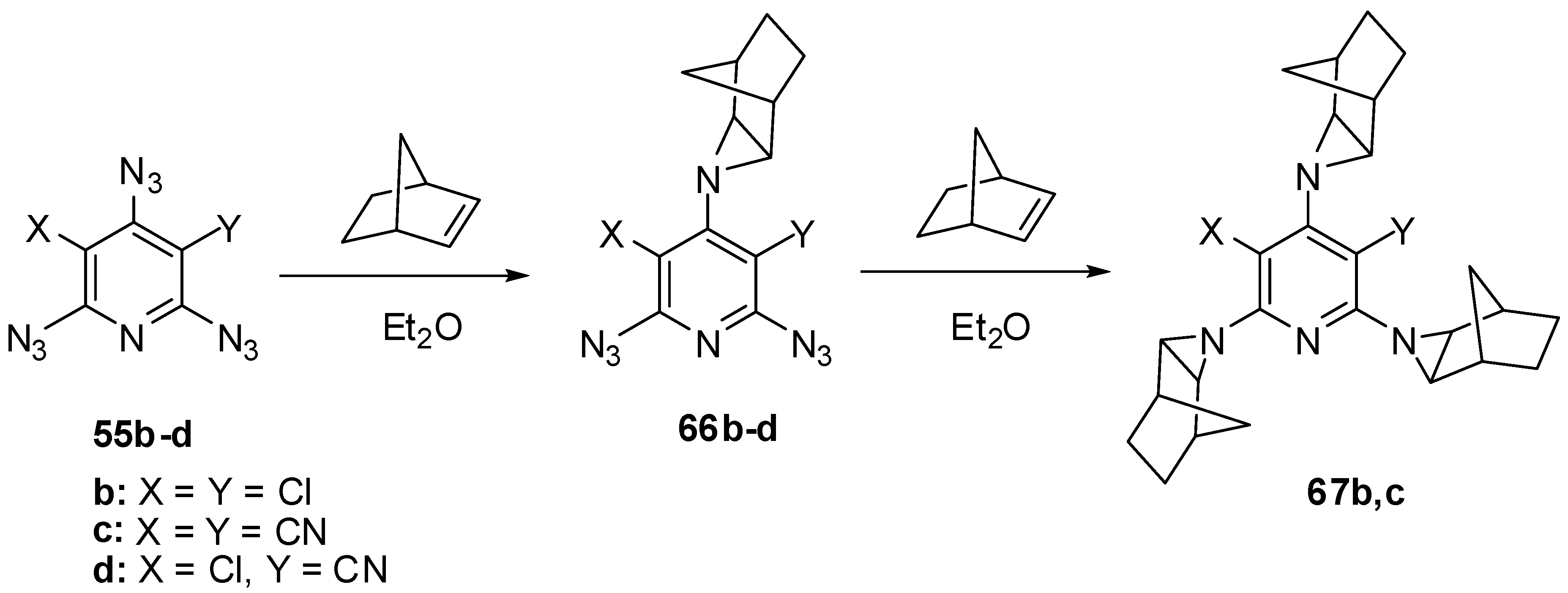

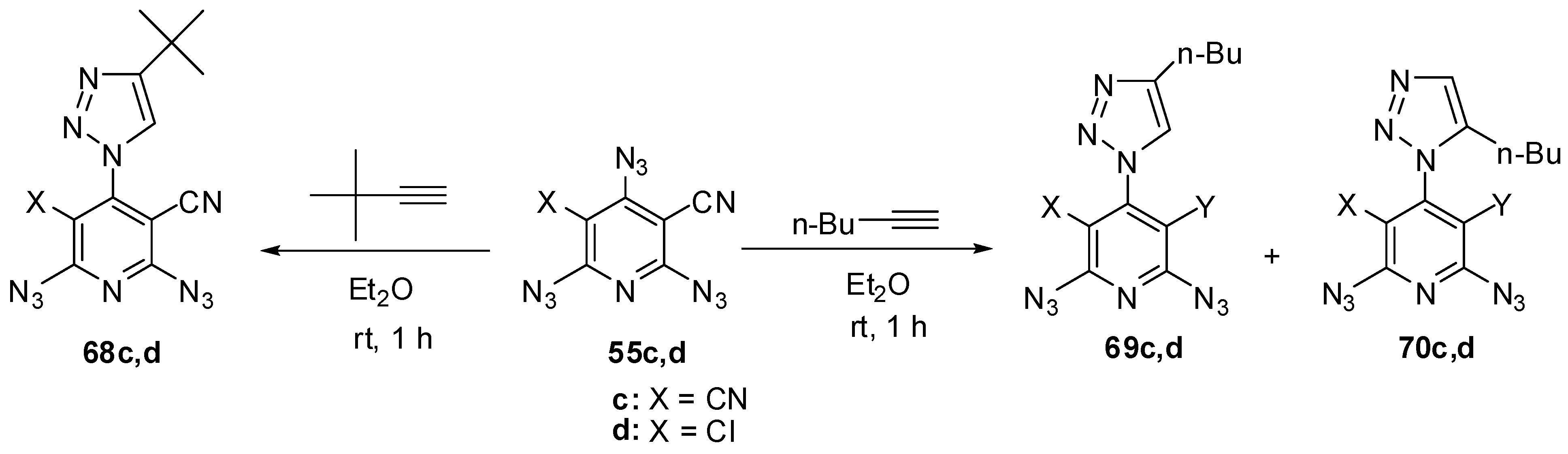

5. Triazidopyridines

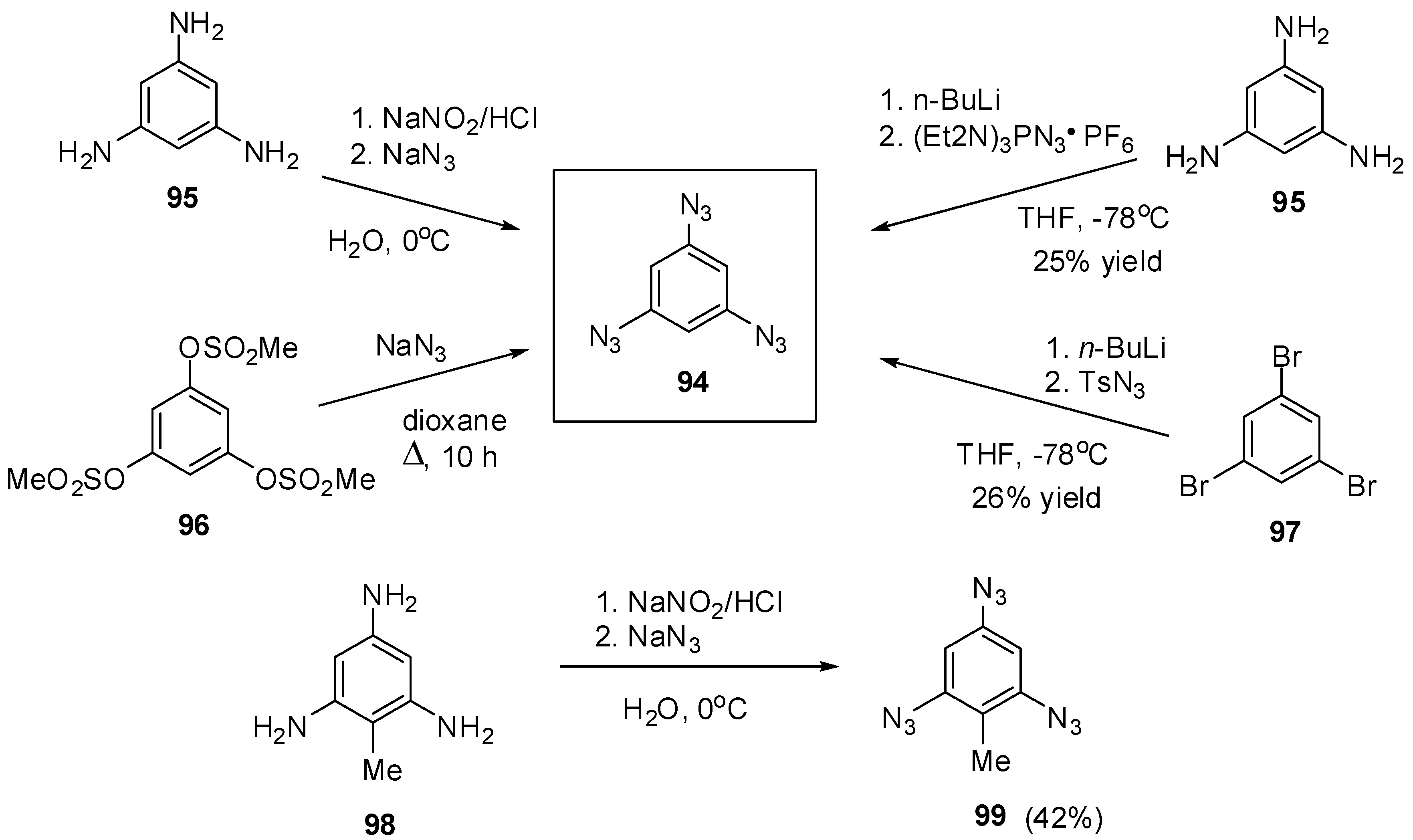

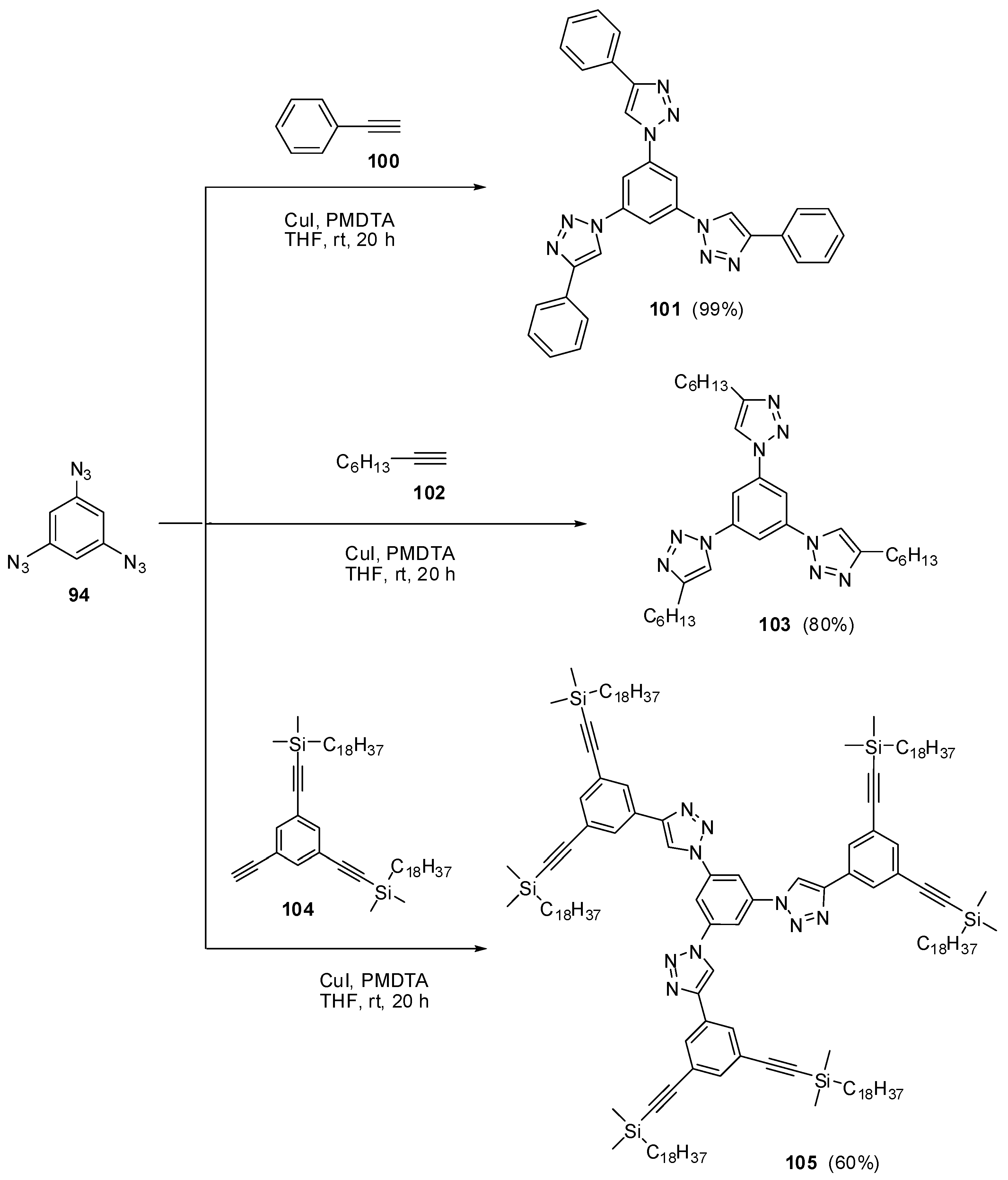

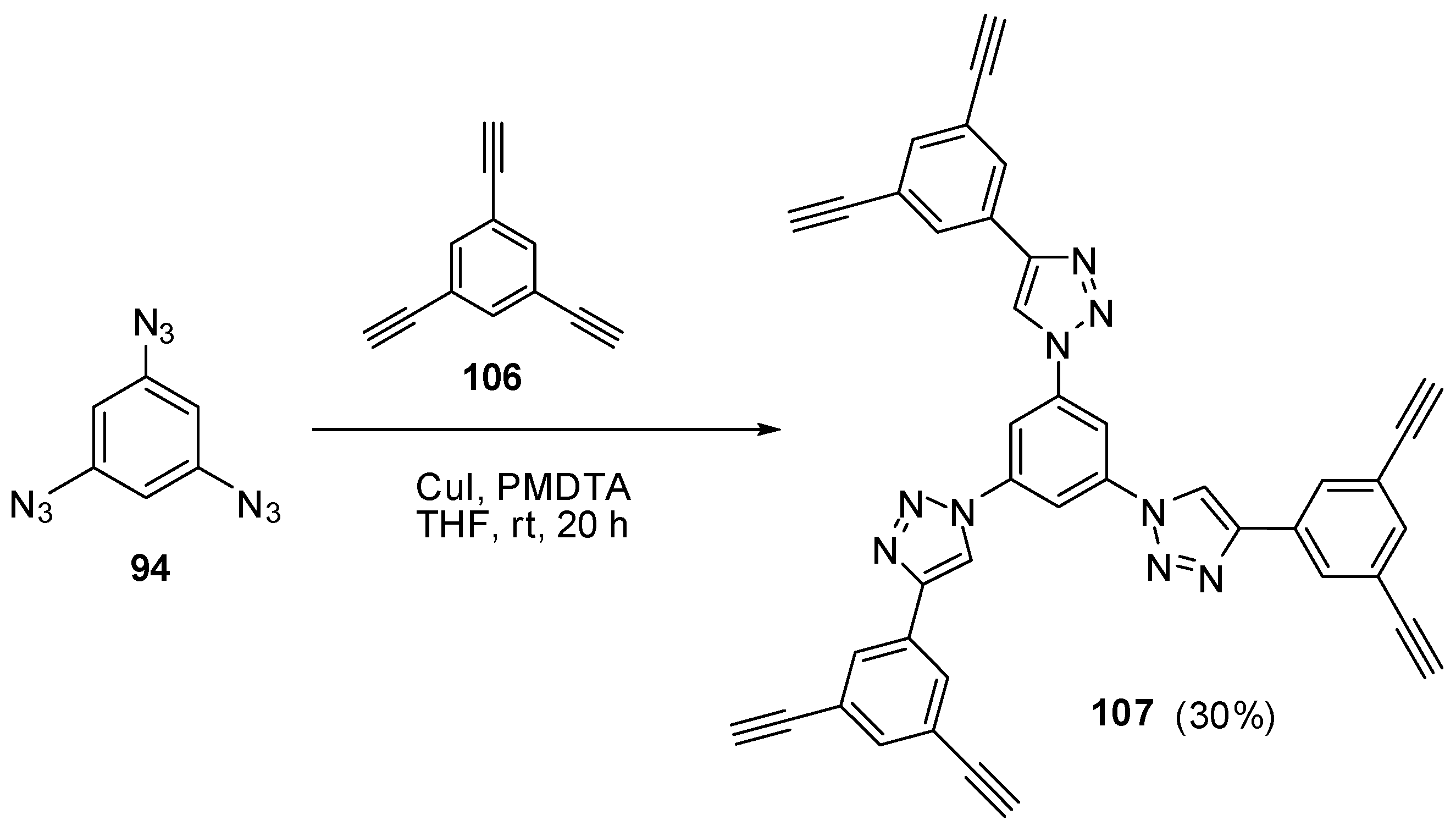

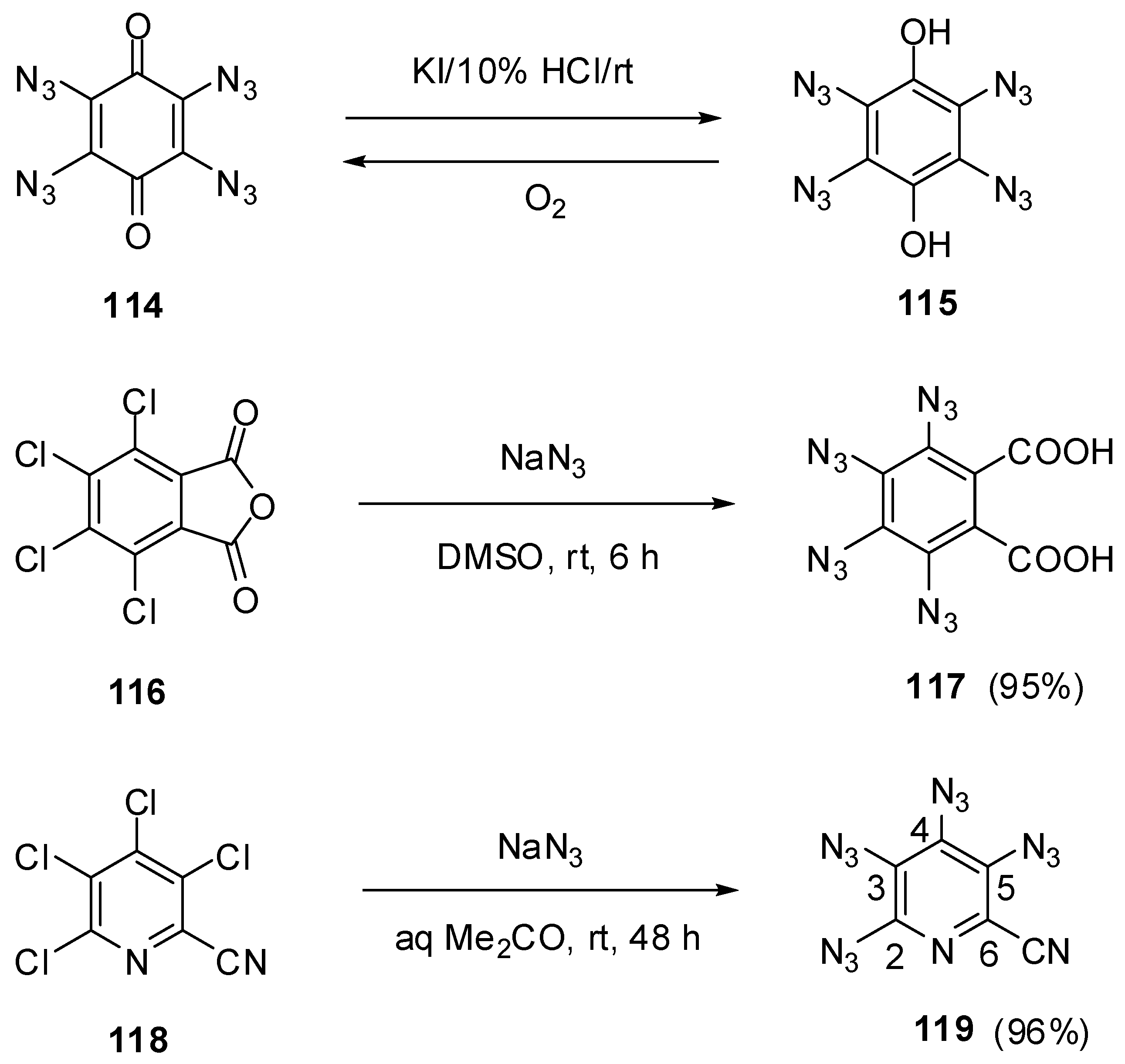

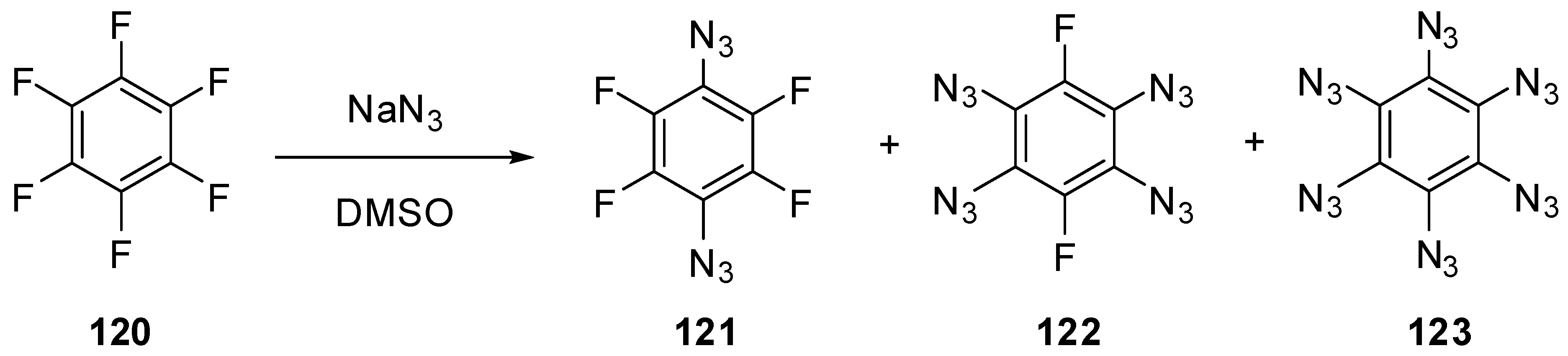

6. Triazidobenzenes

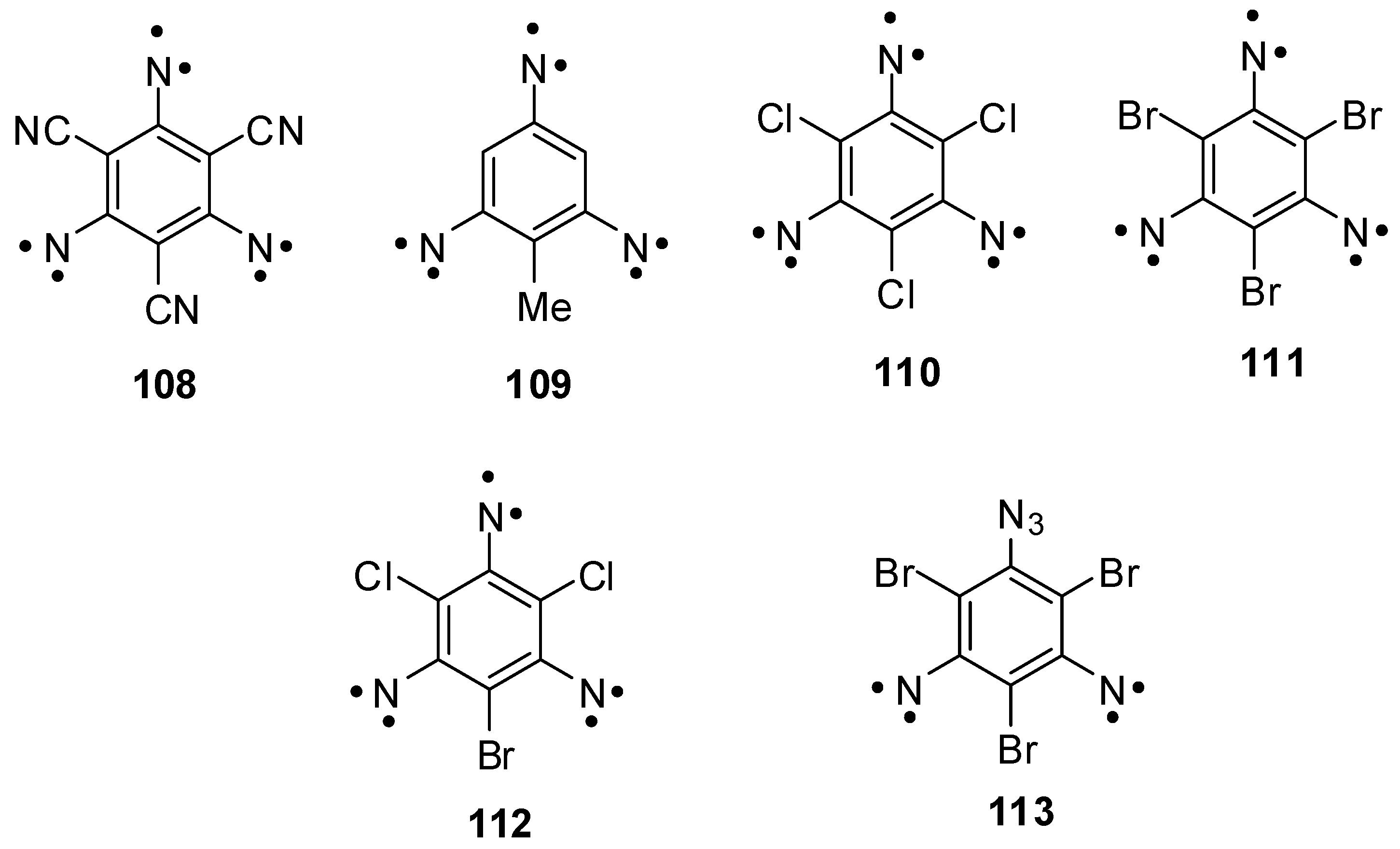

7. Tetraazides

8. Summary

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sutton, T.C. Structure of cyanuric triazide, (C3N3)(N3)3. Philos. Mag. 1933, 15, 1001–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, W.H. Structure of the azide group [crystal structure of cyanuric triazide]. Nature 1934, 134, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.W. Crystal structure of cyanuric triazide. J. Chem. Phys. 1935, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaggs, J.E. Structure of cyanuric triazide. J. Chem. Phys. 1935, 3, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaggs, E. The crystal structure of cyanuric triazide. Proc. Roy. Sci. Lond. 1935, 150, 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroke, E.; Schwarz, M.; Buschmann, V.; Miehe, G.; Fuess, H.; Riedel, R. Nanotubes formed by detonation of C/N precursors. Adv. Mater. 1999, 11, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, E.G. Synthesis of nitrogen-rich carbon nitride networks from an energetic molecular azide precursor. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 3906–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gillan, E.G. Low-temperature deposition of carbon nitride films from a molecular azide, (C3N3)(N3)3. Thin Solid Films 2002, 422, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utschig, T.; Schwarz, M.; Miehe, G.; Kroke, E. Synthesis of carbon nanotubes by detonation of 2,4,6-triazido-1,3,5-triazine in the presence of transition metals. Carbon 2004, 42, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, E.; Schueller, K.; Yager, W.A. EPR detection of the septet ground state of a trinitrene. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1968, 2, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

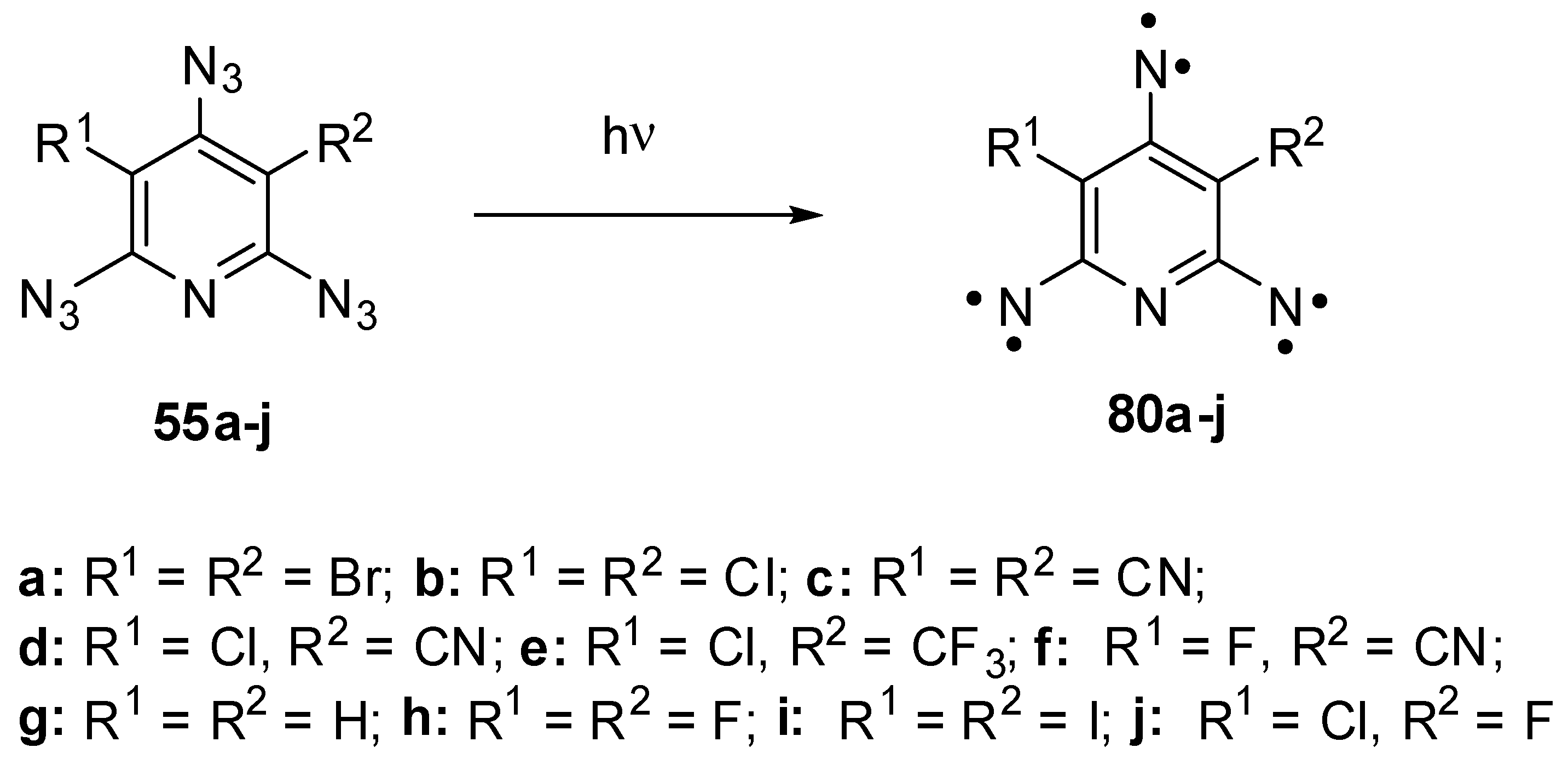

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Kuhn, A.; Wong, M.W.; Wentrup, C. Mono-, di- and trinitrenes in the pyridine series. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1572–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Walton, R.; Sanborn, J.A.; Lahti, P.M. Quintet and septet state systems based on pyridylnitrenes: Effect of substitution on open-shell high-spin states. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1580–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Electronic absorption spectra of quintet and septet pyridylnitrenes. Mendeleev Commun. 2002, 12, 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Narazaki, A.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Niino, H.; Bucher, G. Dicyanocarbodiimide and trinitreno-s-triazine generated by consecutive photolysis of triazido-s-triazine in a low-temperature nitrogen matrix. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5206–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Narazaki, A.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Niino, H.; Bucher, G.; Grote, D.; Wolff, J.J.; Wenk, H.H.; Sander, W. Generation and photoreactions of 2,4,6-trinitreno-1,3,5-triazine, a septet trinitrene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 7846–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzina, S.I.; Mikhailov, A.I.; Chapyshev, S.V. Radiolysis and photolysis of crystalline 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-dichloropyridine: Generation of quintet dinitrenes. High Energy Chem. 2007, 41, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzina, S.I.; Mikhailov, A.I.; Chapyshev, S.V. Effect of microwave radiation on the magnetic properties of quintet dinitrenes. Dokl. Phys. Chem. 2007, 412, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgunov, R.B.; Berdinskii, V.L.; Kirman, M.V.; Tanimoto, Y.; Chapyshev, S.V. Photochemical magnetism of crystalline 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-dichloropyridine. High Energy Chem. 2007, 41, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Kuzina, S.I.; Mikhailov, A.I. Generation of quintet dinitrenes by γ-radiolysis of crystalline 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-dicyanopyridine. Mendeleev Commun. 2007, 17, 207–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Grote, D.; Finke, C.; Sander, W. Matrix isolation and EPR spectroscopy of septet 3,5-difluoropyridyl-2,4,6-trinitrene. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 7045–7051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misochko, E.Y.; Akimov, A.V.; Chapyshev, S.V. High resolution EPR spectroscopy of septet 3,5-dichloropyridyl-2,4,6-trinitrene in solid argon. Fine-structure parameters of six electron-spin cluster. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 174510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Neuhaus, P.; Grote, D.; Sander, W. Matrix isolation and magnetic parameters of septet 3,5-dicyanopyridyl-2,4,6-trinitrene. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2010, 23, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Korchagin, D.V.; Neuhaus, P.; Sander, W. High-spin intermediates of the photolysis of 2,4,6-triazido-3-chloro-5-fluoropyridine. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Misochko, E.Y.; Akimov, A.V.; Dorokhov, V.G.; Neuhaus, P.; Grote, D.; Sander, W. Molecular structure and magnetic parameters of septet 2,4,6-trinitrenotoluene. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 7238–7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misochko, E.Y.; Korchagin, D.V.; Bozhenko, K.V.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Aldoshin, S.M. A density functional theory study of the zero-field splitting in high-spin nitrenes. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 133, 064101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misochko, E.Y.; Akimov, A.V.; Masitov, A.A.; Korchagin, D.V.; Yakushchenko, I.K.; Chapyshev, S.V. High-spin organic molecules with dominant spin-orbit contribution and unprecedentedly large magnetic anisotropy. J. Chem. Phys. 2012, 137, 064308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misochko, E.Y.; Akimov, A.V.; Mazitov, A.A.; Korchagin, D.V.; Chapyshev, S.V. Magnetic anisotropy parameters of matrix-isolated septet 1,3,5-trinitreno-2,4,6-trichlorobenzene. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2012, 61, 2218–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzina, S.I.; Tokarev, S.V.; Korchagin, D.V.; Kolpakov, G.A.; Khudyakov, D.V.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Mikhailov, A.I.; Nadtochenko, V.A.; Aldoshin, S.M. Molecular magnetic structures based on high-spin intermediates of low-temperature radiolysis of azido derivatives and possibilities of their use in undulator systems. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2013, 62, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misochko, E.Y.; Akimov, A.V.; Masitov, A.A.; Korchagin, D.V.; Aldoshin, S.M.; Chapyshev, S.V. Matrix isolation ESR spectroscopy and magnetic anisotropy of D3h symmetric septet trinitrenes. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138, 204317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Ushakov, E.N.; Neuhaus, P.; Sander, W. Matrix isolation, zero-field splitting parameters, and photoreactions of 2,4,6-trinitrenopyrimidines. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 6047–6053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Misochko, E.Y.; Akimov, A.V.; Mazitov, A.A.; Korchagin, D.V.; Chapyshev, S.V. Magnetic anisotropy parameters of matrix-isolated septet 1,3,5-trinitreno-2,4,6-tribromobenzene. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2015, 64, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misochko, E.Y.; Masitov, A.A.; Akimov, A.V.; Korchagin, D.V.; Chapyshev, S.V. Heavy atom effect on magnetic anisotropy of matrix-isolated monobromine substituted septet trinitrene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 2413–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimov, A.; Masitov, A.; Korchagin, D.; Chapyshev, S.; Misochko, E.; Savitsky, A. W-band EPR studies of high-spin nitrenes with large spin-orbit contribution to zero-field splitting. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 084313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Selective reactions on the azido groups of aromatic polyazides. Synlett 2009, 2009, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Aromatic polyazides and high-spin nitrenes. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2011, 60, 1274–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bräse, S.; Gil, C.; Knepper, K.; Zimmermann, V. Organic azides: An exploding diversity of a unique class of compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 5188–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, C.; Jung, N.; Bräse, S. Cycloaddition reactions with azides: An overview. In Organic Azides: Synthesis and Applications; Bräse, S., Banert, K., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2010; pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- Juwarker, H.; Lenhardt, J.M.; Pham, D.M.; Craig, S.L. 1,2,3-Triazole CH···Cl- contacts guide anion binding and concomitant folding in 1,4-diaryl triazole oligomers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3740–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meudtner, R.M.; Hecht, S. Helicity inversion in responsive foldamers induced by achiral halide ion guests. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4926–4930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Flood, A.H. Strong, Size-selective, and electronically tunable C-H···Halide binding with steric control over aggregation from synthetically modular, shape-persistent[34]triazolophanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12111–12122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megiatto, J.D., Jr.; Schuster, D.I. General method for synthesis of functionalized macrocycles and catenanes utilizing “click” chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 12872–12873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Pink, M.; Karty, J.A.; Flood, A.H. Dipole-promoted and size-dependent cooperativity between pyridyl-containing triazolophanes and halides leads to persistent sandwich complexes with iodide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 17293–17295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juwarker, H.; Lenhardt, J.M.; Castillo, J.C.; Zhao, E.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Jamiolkowski, R.M.; Kim, K.; Craig, S.L. Anion binding of short, flexible aryl triazole oligomers. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 8924–8934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latyshev, G.V.; Baranov, M.S.; Kazantsev, A.V.; Averin, A.D.; Lukashev, N.V.; Beletskaya, I.P. Copper-catalyzed [1,3]-dipolar cycloaddition for the synthesis of macrocycles containing acyclic, aromatic and steroidal moieties. Synthesis 2009, 41, 2605–2615. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Huang, X.; Shen, Y.; Cheng, Y. Click chemistry approach to fluorescence-based polybinaphthyls incorporating a triazole moiety for Hg2+ recognition. Synlett 2010, 2010, 453–456. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Dong, Y.; Meng, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, C. Fluorescence polymer incorporating triazole and benzo[2,1,3]thiadiazole moieties for Ni2+ detection. Synlett 2010, 2010, 1841–1844. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y.; Flood, A.H. Flipping the switch on chloride concentrations with a light-active foldamer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12838–12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megiatto, J.D., Jr.; Schuster, D.I. Introduction of useful peripheral functional groups on [2]catenanes by combining Cu(I) template synthesis with “click” chemistry. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juricek, M.; Felici, M.; Contreras-Carballada, P.; Lauko, J.; Bou, S.R.; Kouwer, P.H.J.; Brouwer, A.M.; Rowan, A.E. Triazole-pyridine ligands: A novel approach to chromophoric iridium arrays. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 2104–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plietzsch, O.; Schilling, C.I.; Grab, T.; Grage, S.L.; Ulrich, A.S.; Comotti, A.; Sozzani, P.; Muller, T.; Brase, S. Click chemistry produces hyper-cross-linked polymers with tetrahedral cores. New J. Chem. 2011, 35, 1577–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornik, D.; Meudtner, R.M.; El Malah, T.; Thiele, C.M.; Hecht, S. Designing structural motifs for clickamers: Exploiting the 1,2,3-triazole moiety to generate conformationally restricted molecular architectures. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, J.; Huang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhu, C. A Highly selective and sensitive polymer-based fluorescence sensor for Hg2+-ion detection via click reaction. Chem. Asian J. 2011, 6, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajipour, A.R.; Abrishami, F. Synthesis and characterization of novel polyimides containing triazoles units in the main chain by click chemistry. J. Appl. Polym. Chem. 2012, 124, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar]

- You, L.; Chen, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Lan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, H.; Cao, C.; Li, Z. C-H···O hydrogen bonding induced triazole foldamers: Efficient halogen bonding receptors for organohalogens. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1657–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Flood, A.H. Hydrophobic collapse of foldamer capsules drives picomolar-level chloride binding in aqueous acetonitrile solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 14401–14412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merckx, T.; Verwilst, P.; Dehaen, W. Preorganization in bistriazolyl anion receptors. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 4237–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, R.; Li, Z. Folding-induced folding: The assembly of aromatic amide and 1,2,3-triazole hybrid helices. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Gallagher, N.M.; Bie, F.; Li, Q.; Che, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H. Aromatic triazole foldamers induced by C-H···X (X = F, Cl) intramolecular hydrogen bonding. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 5134–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Hua, Y.; Flood, A.H. β-Sheet-like hydrogen bonds interlock the helical turns of a photoswitchable foldamer to enhance the binding and release of chloride. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 8383–8396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merckx, T.; Haynes, C.J.E.; Karagiannidis, L.E.; Clarke, H.J.; Holder, K.; Kelly, A.; Tizzard, G.J.; Coles, S.J.; Verwilst, P.; Gale, P.A.; et al. Anion binding and transport properties of cyclic 2,6-bis(1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)pyridines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 1654–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finger, H. Über Abkömmlinge des Cyanurs. J. Prakt. Chem. 1907, 75, 103–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, E.; Ohse, E. Zur kenntnis einfachen Cyan- und Cyanurverbindungen. II. Über das Cyanurtriazid (C3N12). Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1921, 54B, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keßenich, E.; Klapötke, T.M.; Knitzek, J.; Nöth, H.; Schultz, A. Characterization, crystal structure of 2,4-bis(triphenylphosphanimino)tetrazolo[5,1-a]-[1,3,5]triazine, and improved crystal structure of 2,4,6-triazido-1,3,5-triazine. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 1998, 2013–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessenich, E.; Polborn, K.; Schultz, A. Reaction of 2,4,6-triazido-1,3,5-triazine with triphenylphosphane. Synthesis and characterization of the novel 2-triphenylphosphanimino-4-azidotetrazolo[5,1-a]-[1,3,5]triazine and 2,4,6-tris(triphenylphosphanimino)-1,3,5-triazine. Inorg. Chem. 2001, 40, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, C.V. Carbonic acid azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1928, 50, 1922–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allschwil, E.N.; Stein, L.E. Azido-1,3,5-triazines. Patent NL 6413689, 28 May 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, W.; Bauder, M. Reactions of hydridoplatinum(II) complexes with organic azides: Amido complexes. Chem. Ber. 1970, 103, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochinok, V.Y.; Avramenko, L.F.; Grigorenko, T.F.; Pochinok, A.V.; Sidorenko, I.A.; Bovchalyuk, L.N. Synthesis of 2,4,6-triazidopyrimidine, 2,4,6-triazido-s-triazine, and triazenes produced from them. Ukr. Khim. Zh. 1979, 45, 975–978. [Google Scholar]

- Thust, R.; Schneider, M.; Wagner, U.; Schreiber, D. Structure/activity investigations in eight arylalkyltriazenes comparison of chemical stability mode of decomposition and SCE induction in Chinese hamster V79-E cells. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 1991, 7, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggermont, A.M.M.; Kirkwood, J.M. Re-evaluating the role of dicarbazine in metastatic melanoma: What have we learned in 30 years? Eur. J. Cancer 2004, 40, 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kölmel, D.K.; Jung, N.; Bräse, S. Azides—Diazonium ions—Triazenes: Versatile nitrogen-rich functional groups. Aust. J. Chem. 2014, 67, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesting, W. Über Cyanurphosphinimines und über pyrogene Spaltungsversuche an Äthyl- und Methylester der normalen Cyanursäure. J. Prakt. Chem. 1923, 105, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Ushakov, E.N.; Chernyak, A.V. 15N-NMR spectra and reactivity of 2,4,6-triazidopyridines, 2,4,6-triazidopyrimidine and 2,4,6-triazido-s-triazine. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2013, 51, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapötke, T.M.; Rienacker, C.M. Drop hammer test investigations on some inorganic and organic azides. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2001, 26, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, M.H.; Hiskey, M.; Pollard, C.; Montoya, D.; Hartline, E.; Gilardi, R. 4,4′,6,6′-Tetrasubstituted hydrazo- and azo-1,3,5-triazines. J. Energ. Mater. 2004, 22, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.R.; Swenson, D.C.; Gillan, E.G. Synthesis and structure of 2,5,8-triazido-s-heptazine: An energetic and luminescent precursor to nitrogen-rich carbon nitrides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5372–5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, M.H.; Hiskey, M.; Hartline, E.; Montoya, D.; Gilardi, R. Polyazido high-nitrogen compounds: Hydrazo- and azo-1,3,5-triazine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 4924–4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, C.; Gao, H.; Boatz, J.A.; Drake, G.W.; Twamley, B.; Shreeve, J.M. Polyazidopyrimidines: High-energy compounds and precursors to carbon nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 7262–7265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klapötke, T.M. Chemistry of High-Energy Materials; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Matyáš, R.; Pachman, J. Primary Explosives; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 71–130. [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty, R.M.; Rahman, M.; King, G.J. Organic nitrenes in single crystals. Observation of hyperfine structure in the E.S.R. (electron spin resonance). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966, 88, 842–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, T.; Sato, K.; Shiomi, D.; Takui, T.; Itoh, K.; Kozaki, M.; Okada, K. High-spin nitrenes with s-triazine skeleton. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1999, 334, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, R.E.; Prakash, A.; Venayak, N.D. Studies in azide chemistry. Part IX. Investigations involving fluorinated azidopyrimidines and 4-azido-3-chloro-2,5,6-trifluoropyridine. J. Fluor. Chem. 1980, 16, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochiniok, A.V.; Sharykina, N.I.; Bakhtiarova, T.A. Antitumor activity of 2,4,6-triazidopyrimidine. Fiziol. Akt. Veshchestva 1990, 22, 76–78. [Google Scholar]

- Pochinok, A.V.; Smirnov, V.A.; Brichkin, S.B.; Pochinok, V.Y.; Avramenko, L.F.; Grigorenko, T.F. Photolysis of azido derivatives of pyrimidine. Khim. Vys. Energ. 1982, 16, 151–154. [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J.; Guelin, M.; Pardo, J.R. Detection of the linear radical HC4N in IRC + 10216. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2004, 615, L145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, R.D.; Greenwood, J.R.; Hambley, T.W.; Hanrahan, J.R.; Hibbs, D.E.; Itani, S.; Tran, H.W.; Turner, P. Studies on pyridazine azide cyclisation reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004, 2, 1782–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshchitskii, S.D.; Zeikan, A.A.; Pavlenko, A.F.; Kukhar, V.P. Synthesis and reactions of azidopolybromopyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1979, 15, 1197–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Chernyak, A.V.; Yakushchenko, I.K. Chemoselective Staudinger-phosphite reaction on the azido-groups of 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-dibromopyridine. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Synthesis and regioselective cycloaddition reactions of 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-dichloropyridine. Mendeleev Commun. 1999, 9, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

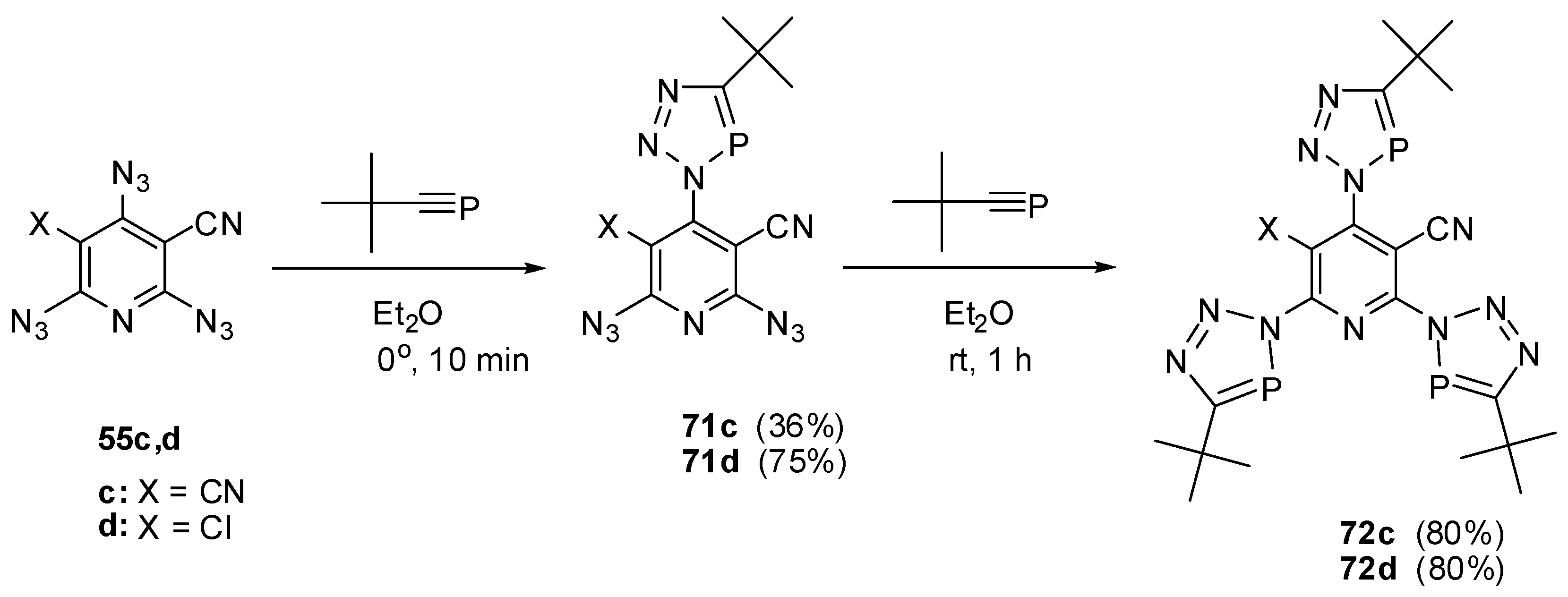

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Bergstrasser, U.; Regitz, M. Effect of electronic factors on 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of 2,4,6-triazidopyridines to tert-butylphosphaacetylene. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1996, 32, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, Yu. M.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Nedel’ko, V.V. Synthesis, thermal stability, heats of formation and explosive properties of cyano-substituted derivatives of di-, tri- and tetraazidopyridines. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2009, 58, 2097–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Ibata, T. Synthesis of highly substituted pyridines through nucleophilic substitution of tetrachloro-3-cyanopyridine. Heterocycles 1993, 36, 2185–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Synthesis and regioselective cycloaddition of 2,4,6-triazido-3-chloro-5-cyanopyridine with norbornene. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1993, 29, 1426–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Korchagin, D.V.; Shilov, G.V.; Aldoshin, S.M. Synthesis and structure of asymmetric 2,4,6-triazidopyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2011, 47, 817–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Chernyak, A.V. Synthesis of 2,4,6-triazidopyridine and its 3,5-diiodo derivative. Synthesis 2012, 44, 3158–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Synthesis of 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-difluoropyridine. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1999, 35, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Synthesis, thermolysis, and mass-spectrometry of perfluorinated di- and triazidopyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2001, 37, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Di- and triazidation of 3-chlorotetrafluoropyridine. J. Fluor. Chem. 2011, 132, 991–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, C.; Grote, D.; Seidel, R.W.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Sander, W. Matrix isolation and IR spectroscopic characterization of 3,5-difluoropyridyl-2,4,6-trinitrene. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2012, 25, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, Y.V.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernohgolovka, Russian Federation. Unpublished work. 2015.

- Kuzina, S.I.; Mikhailov, A.I.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Korchagin, D.V.; Shilov, G.V.; Aldoshin, S.M. Properties of quintet dinitrenes in 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-dichloropyridine crystals. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 82, 1870–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzina, S.I.; Korchagin, D.V.; Shilov, G.V.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Mikhailov, A.I.; Aldoshin, S.M. Generation of quintet dinitrenes by low-temperature radiolysis of crystalline 2,4,6-triazido-3,5-dicyanopyridine. Dokl. Phys. Chem. 2008, 418, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldoshin, S.M.; Korchagin, D.V.; Bozhenko, K.V.; Shilov, G.V.; Chapyshev, S.V. A study of molecular and crystalline structure of 2,4,6-triazido-3-chloro-5-trifluoromethylpyridine and the rotation barrier of the γ-azido group around the С-N bond. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2008, 72, 1556–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronowitz, S.; Zanirato, P. Preparation, reactivity, NMR properties and semiempirical calculations of 2-azido- and 3-azido-selenophene. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1994, 2, 1815–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budyka, M.F.; Zyubina, T.S. Theoretical investigation of the azido group dissociation in aromatic azides. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 1997, 419, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alajarin, M.; Conesa, C.; Rzepa, H.S. Ab initio SCF-MO study of the Staudinger phosphorylation reaction between a phosphane and an azide to form phosphazene. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2 1999, 1811–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Selective derivatization of 2,4,6-triazidopyridines by the Staudinger reaction. Mendeleev Commun. 1999, 9, 166–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Platz, M.S. Selective reduction of the azido groups of 2,4,6-triazidopyridines. Mendeleev Commun. 2001, 11, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Anisimov, V.M. Stereo- and regioselective cycloaddition of norbornene to 2,4,6-triazidopyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1997, 33, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Regioselective and regiospecific cycloaddition of acetylenes to 2,4,6-triazido-pyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2000, 36, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Bergstrasser, U.; Regitz, M. 1,3-Dipolar tris-cycloaddition of tert-butylphospha-acetylene to 2,4,6-triazido-3-chloro-5-cyanopyridine. Russ. Chem. Bull. 1996, 45, 242–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Anisimov, V.M. Quantum-chemical study of the nature of regioselectivity in reactions of 2,4,6-triazidopyridines with tert-butylphosphaacetylene. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 1997, 33, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

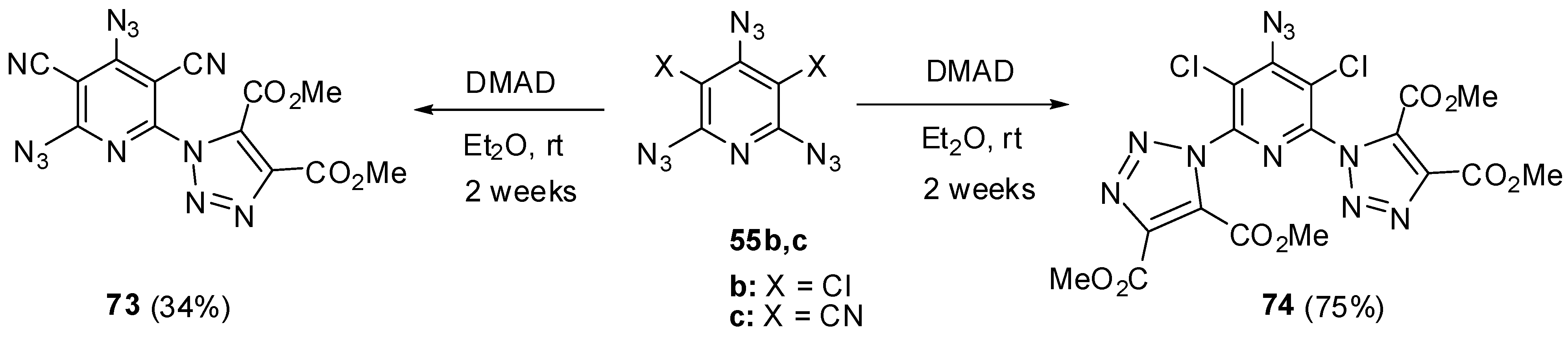

- Chapyshev, S.V. Regioselective cycloaddition of the dimethyl ester of acetylenedicarboxylic acid to 2,4,6-triazidopyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2001, 37, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Nucleophilic replacement of the azido groups by amines in 2,4,6-triazido-3-chloro-5-cyanopyridine. Mendeleev Commun. 2007, 17, 287–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Selective thermolysis of the azido groups of 2,4,6-triazidopyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2003, 39, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Walton, R.; Lahti, P.M. Orbital control in the selective photolysis of the azido groups of 2,4,6-triazidopyridines. Mendeleev Commun. 2000, 10, 187–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetner, W., Jr. Magnetic Atoms and Molecules; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1989; p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Korchagin, D.V.; Neuhaus, P.; Costa, P.; Sander, W.; Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernohgolovka, Russian Federation. Unpublished work. 2015.

- Sugisaki, K.; Toyota, K.; Sato, K.; Shiomi, D.; Kitagawa, M.; Takui, T. An ab initio MO study of heavy atom effects on the zero-field splitting tensors of high-spin nitrenes: How the spin-orbit contributions are affected. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 9171–9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turek, O. 2,4,6-Trinitro-1,3,5-tristriazobenzene, a new explosive for detonators. Chim. Ind. 1931, 26, 781–794. [Google Scholar]

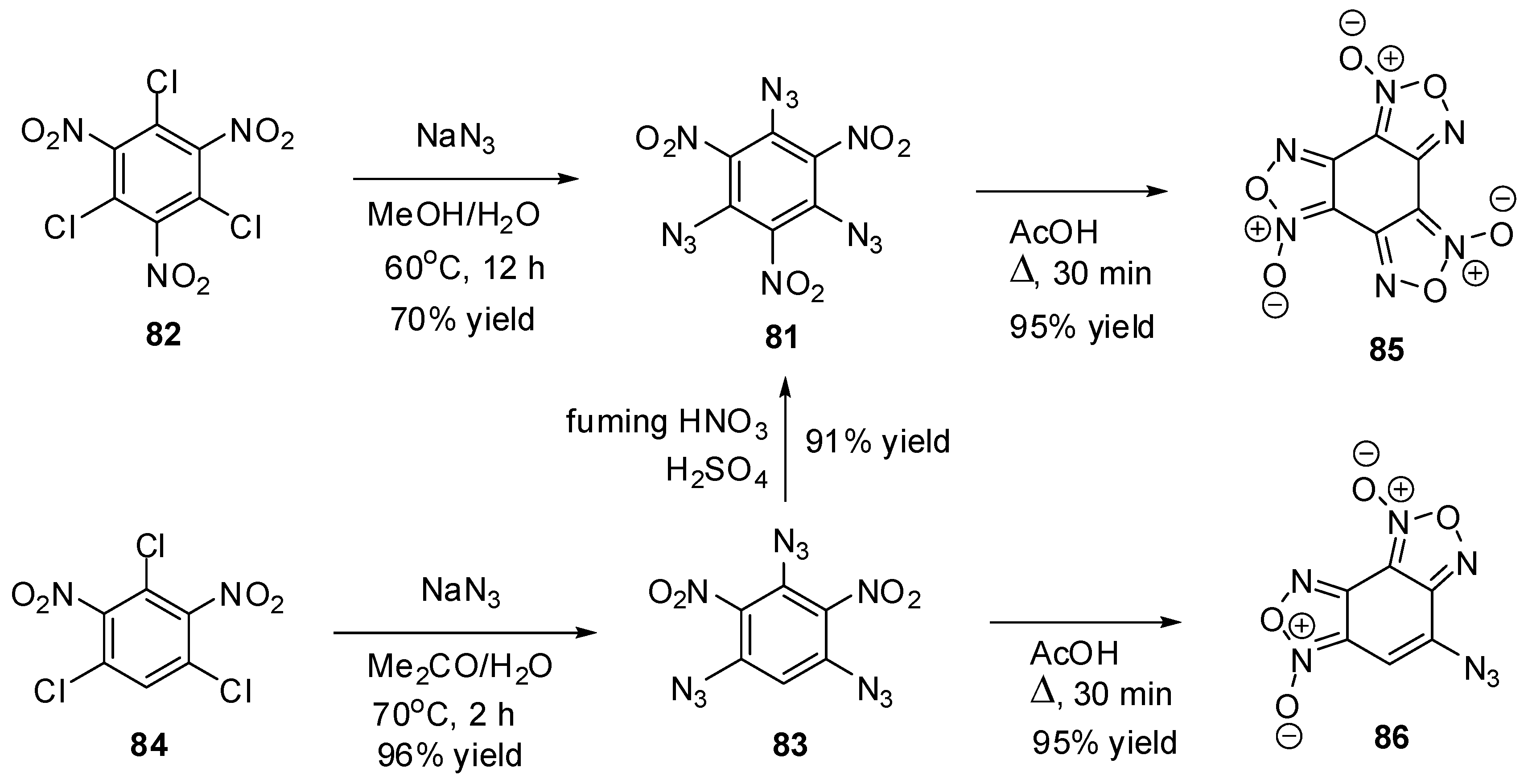

- Bailey, A.S.; Case, J.R. 4,6-Dinitrobenzofuroxan, nitrobenzodifuroxan, and benzotrifuroxan. A new series of complex-forming reagents for aromatic hydrocarbons. Tetrahydron 1958, 3, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, D.; Holl, G.; Klapötke, T.M. Nitrophenyl azides: A combined experimental and theoretical study. Heteroat. Chem. 1999, 10, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, D.; Karaghiosoff, K.; Klapötke, T.M.; Holl, G.; Kaiser, M. Triazidotrinitro benzene: 1,3,5-(N3)3-2,4,6-(NO2)3C6. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 2002, 27, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namba, K.; Yamashita, T. Nitroazidobenzenes. I. Synthesis of nitroazidobenzenes from nitrochlorobenzenes and sodium azide. Kogyo Kayaku Kyokaishi 1958, 19, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, A.S. Improvement in the preparation of benzotrifuroxan—Further examples of complex formation by this reagent. J. Chem. Soc. 1960, 4710–4712. [Google Scholar]

- Wallenfels, K.; Witzler, F.; Friedrich, K. 1,3,5-Trichlor-2,4,6-tricyan-benzol und 1,3,5-trifluor-2,4,6-tricyan-benzol. Tetrahedron 1967, 23, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Voss, K.; Villenger, A.; Schulz, A. An efficient route to 1,3,5-triazido-2,4,6-tricyanobenzene. Z. Naturforsh. 2012, 67b, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiko, V.N.; Gogoman, I.V.; Shchupak, G.M.; Yagupol’skii, L.M. Nucleophilic substitution in aromatic compounds with fluorine-containing substituents. X. Reactions of 2,4,6-trichloro- and 2,6-dichloro-3,5-bis[(trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl]nitrobenzenes with nucleophiles. Zh. Org. Khim. 1987, 23, 2586–2591. [Google Scholar]

- Chapyshev, S.V.; Chernyak, A.V. Triazidation of 2,4,6-trifluorobenzenes. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 156, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, D.S.; Marcantonio, A.F. Polyazide Crosslinking Agents. U.S. Patent 3297674, 10 January 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, W.S. Anion Receptors, and Electrolyte Using the Same. WO Patent 2007126262, 8 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Juriček, M. Triazole Materials: Towards Extending Aromaticity. Ph.D. Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 114–139. [Google Scholar]

- Chapyshev, S.V. Synthesis of 2,4,6-Triazidotoluene for Use as Photoaffinic and Crosslinking Agent. RU Patent 2430080, 27 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sorm, F. The preparation of tetraazido-1,4-benzoquinone. Chem. Obz. 1939, 14, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Marburg, S.; Grieco, P.A. Reaction of cyclic anhydrides with sodium azide in polar aprotic media. Tetrahedron Lett. 1966, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannell, C.D. Pyridyl azides and their Derivatives. U.S. Patent 3773774, 20 November 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Pannell, C.D. Pyridyl Azides and Derivatives. U.S. Patent 3883542, 13 May 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Nedel’ko, V.V.; Korsunskii, B.L.; Larikova, T.S.; Mikhailov, Yu. M.; Chapyshev, S.V.; Chukanov, N.V. The thermal decomposition of azidopyridines. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 5, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.G.; Kuhn, L.P. The Reaction of Hexafluorobenzene with Sodium Azide; Defense Technical Information Center: Fort Belvoir, USA, 1970; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.F.; Xu, W.G.; Lu, S.X. DFT theoretical study on nitrogen-rich compounds C6H(6–n)(N3)n (n = 1–6). Gaodeng Xuexiao Huaxue Xuebao 2009, 30, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Gong, X. Theoretical studies on the nitro and azido derivatives of benzene. Xuaxue Xuebao 2011, 69, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.C.; Wang, Y. The first-principle study on the crystal structures of azido derivatives of benzene. J. Energ. Mater. 2014, 32, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chapyshev, S.V. Six-Membered Aromatic Polyazides: Synthesis and Application. Molecules 2015, 20, 19142-19171. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201019142

Chapyshev SV. Six-Membered Aromatic Polyazides: Synthesis and Application. Molecules. 2015; 20(10):19142-19171. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201019142

Chicago/Turabian StyleChapyshev, Sergei V. 2015. "Six-Membered Aromatic Polyazides: Synthesis and Application" Molecules 20, no. 10: 19142-19171. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules201019142